Abstract

• Background and Aims Most Vaccinium species have strict soil requirements for optimal growth, requiring low pH, high iron availability and nitrogen primarily in the ammonium form. These soils are limited and are often located near wetlands. Vaccinium arboreum is a wild species adapted to a wide range of soils, including high pH, low iron, and nitrate‐containing soils. This broader soil adaptation in V. arboreum may be related to increased efficiency of iron or nitrate uptake compared with the cultivated Vaccinium species.

• Methods Nitrate, ammonium and iron uptake, and nitrate reductase (NR) and ferric chelate reductase (FCR) activities were compared in two Vaccinium species grown hydroponically in either nitrate or ammonia, with or without iron. The species studied were the wild V. arboreum and the cultivated V. corymbosum interspecific hybrid, which exhibits the strict soil requirements of most Vaccinium species.

• Key Results Ammonium uptake was significantly greater than nitrate uptake in both species, while nitrate uptake was greater in the wild species, V. arboreum, compared with the cultivated species, V. corymbosum. The increased nitrate uptake in V. arboreum was correlated with increased root NR activity compared with V. corymbosum. The lower nitrate uptake in V. corymbosum was reflected in decreased plant dry weight in this species compared with V. arboreum. Root FCR activity increased significantly in V. corymbosum grown under iron‐deficient conditions, compared with the same species grown under iron‐sufficient conditions or with V. arboreum grown under either iron condition.

• Conclusions. V. arboreum appears to be more efficient in acquiring nitrate compared with V. corymbosum, possibly due to increased NR activity and this may partially explain the wider soil adaptation of V. arboreum.

Key words: Ferric chelate reductase, iron uptake, nitrate reductase, nitrogen uptake, Vaccinium

INTRODUCTION

Many perennial crop species are adapted to a relatively wide range of soil types and maintain productivity with minimum soil modifications, other than fertilizer. Most Vaccinium species, however, have strict soil requirements for optimal growth. In general, Vaccinium growth is limited to acidic (pH 4·0–5·5), high organic matter soils, where iron is readily available and ammonium is the predominant nitrogen form (Erb et al., 1993; Williamson and Lyrene, 1998). These types of soils are limited and are often located in or adjacent to wetlands. In fact, most Vaccinium species are considered facultative wetland plants and are commonly found in forested wetlands or peatlands (Shaw and Fredine, 1956; Anon., 2003). Although cultivated Vaccinium species can be grown on more typical agricultural soils (i.e. higher native pH, lower organic matter, lower iron availability, nitrogen primarily in the nitrate form), the inputs required to maintain productivity are extensive, and include addition of peat moss, sulphur and pine bark mulch (Korcak, 1986). These modifications lower soil pH, resulting in increased iron and ammonium availability. Without these modifications, most Vaccinium exhibit symptoms of iron (Brown and Draper, 1980) and/or nitrogen deficiency, and suppression of growth (Korcak et al., 1982).

Iron deficiency is characterized by an interveinal chlorosis of young leaves while the veins remain green (Korcak, 1987). Physiological responses of some dicotyledonous plants to iron deficiency include induction of plasma membrane‐bound root ferric chelate reductase (FCR) (Curie and Briat, 2003; Hell and Stephan, 2003), which reduces ferric chelate to ferrous and results in increased iron uptake under iron‐deficient conditions (Chaney et al., 1972; Schmidt, 1999). However, not all species are able to induce FCR under iron deficiency, and thus do not tolerate iron‐deficient soils (Dasgan et al., 2002; de la Guardia and Alcantara, 2002).

Nitrogen deficiency is characterized by chlorosis of the older leaves, while younger leaves may remain green. Leaf chlorosis increases and growth decreases in Vaccinium species supplied with nitrogen in the form of nitrate as opposed to ammonium (Korcak, 1988). These symptoms appear to be related to decreased uptake and assimilation rates of nitrate compared with ammonium (Spiers, 1978; Merhaut and Darnell, 1995).

Assimilation of nitrate is regulated by the activity of nitrate reductase (NR) (Crawford, 1995). This enzyme is found primarily in the cytoplasm of root epidermal and cortical cells and shoot mesophyll cells (Crawford, 1995; Berczi and Moller, 2000), although a small percentage of activity has been found associated with the plasma membrane (Berczi and Moller, 2000). Nitrate reductase catalyses the reduction of nitrate to nitrite as the first step in nitrate assimilation.

In most plants, NR activity is found in both shoots and roots; however, the proportion of nitrate assimilation occurring in roots vs. shoots varies among species. Many woody species exhibit significant leaf NR activity, contrary to the previous conclusion that most nitrate is reduced in the roots of woody plants (Pate, 1980). Leaf NR activity in woody plants varies widely, with activities as high as 11·9 µmol NO2 g f. wt–1 h–1 reported in Trema guineensis (Smirnoff et al., 1984). However, in the Vaccinium species that have been studied, leaf NR activity is very low or non‐detectable (Smirnoff et al., 1984; Merhaut, 1993; Claussen and Lenz, 1999). Additionally, root NR activity in Vaccinium is similar to or lower than root NR activity found in most other woody plants (Townsend, 1970; Merhaut, 1993; Claussen and Lenz, 1999). Thus, the overall nitrate reduction capacity in Vaccinium is significantly lower than in other woody plants. This may result in insufficient uptake and reduction of nitrate (Spiers, 1978), leading to slower growth rates (Claussen and Lenz, 1999), and becoming a limiting factor for Vaccinium growth under nitrate conditions (Korcak, 1988).

Vacciniumarboreum is a wild species native to the south‐eastern US (Lyrene, 1997) and typically grows on soils with pH 6·0–6·5, low organic matter (Lyrene, 1997), low iron availability, and nitrogen primarily in the nitrate form due to rapid nitrification and/or ammonia volatilization (Mengel, 1994); i.e. soils that cultivated Vaccinium tolerate poorly (Lyrene, 1997). The ability of V. arboreum to grow in these soils (often referred to as upland soils) suggests an increased efficiency for iron and/or nitrate assimilation compared with cultivated Vaccinium. It is hypothesized that V. arboreum is able to assimilate iron and nitrate more efficiently, resulting in higher iron/nitrogen uptake compared with V. corymbosum, under conditions that mimic upland soils. The objectives of the present study were to determine differences in NR and FCR activity, nitrogen and iron uptake, and growth between a cultivated and wild Vaccinium species grown under various nitrogen and iron conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant culture

Seeds of the wild species (open pollinated) Vaccinium arboreum Marsh. were collected from a natural habitat of distinct plants (most likely representing a single genotype) at Manatee Springs, Florida, during the autumn of 1998. Propagation by seed was required since previous work in our laboratory and others (P. Lyrene, pers. comm.) indicated that propagation from stem cuttings was unsuccessful. Collected seeds were immediately germinated on the surface of Canadian peat under intermittent mist (4 h per day) in a glasshouse, with an average temperature of 25 °C and 500 µmol m–2 s–1 photosynthetic photon flux (PPF). In April 1999, shoot cuttings of V. corymbosum L. ‘Misty’ were rooted in peat : perlite (1 : 1, v/v) medium under intermittent mist in a glasshouse with an average temperature of 25 °C and average PPF of 500 µmol m–2 s–1. In August 1999, plants of both species were transplanted into 1‐L pots containing pine bark and maintained in the glasshouse. On 3 Mar. 2000, 16 plants from each species were selected and whole plant fresh weights were determined. Plants were arranged in blocks by size before they were transferred to 2‐L plastic bottles filled with a complete nutrient solution. Plastic bottles were wrapped with two layers of aluminium foil to eliminate light infiltration. The nutrient solution contained the following composition (mm): 0·5 K2HPO4, 1·0 MgSO4, 0·5 CaCl2, 0·09 Fe‐diethylenetriaminopentaacetic acid (Fe‐DTPA), 0·045 H3BO3, 0·01 MnSO4, 0·01 ZnSO4 and 0·2 µm Na2MoO4. The nitrogen source was either 2·5 mm (NH4)2SO4 or 5·0 mm NaNO3. The nutrient solutions were buffered at pH 5·5 with 10 mm 2‐(4‐morpholino)‐ethane sulfonic acid (MES). Eight plants of each species were acclimated in the nutrient solutions containing either (NH4)2SO4 or NaNO3 for 3 weeks. After acclimation (22 Mar. 2000), the experimental treatments began by eliminating iron from the solutions in half of the plants of each species and each nitrogen source (–Fe), while the other half continued to receive 90 µm Fe (+Fe). The pH of the nutrient solution in each bottle was monitored daily with a portable pH meter (Accumet 1001; Fisher, USA) and maintained at 5·5, using 0·1 n KOH or 0·1 n HCl. Aeration was provided to each bottle by an aquarium pump (Elite 801; Rolf C. Hagen, Mansfield, MA, USA), connected by tygon tubing, located at the bottom of the bottle. The airflow was adjusted to 1 L min–1. Nutrient solutions were changed weekly. The amount of solution left in each bottle was recorded and used to determine the water use in each bottle on a weekly basis. Plant water use was corrected for evaporative losses using aerated bottles containing nutrient solution without plants. Six weeks after treatments began (3 May 2000), iron (90 µm) was resumed in all –Fe plants and plants were grown for an additional 7 weeks. The glasshouse conditions during the experimental period averaged 29/20 °C day/night temperature, 90 % relative humidity and averaged PPF of 540 µmol m–2 s–1.

Ammonium, nitrate and iron uptake

Ammonium, nitrate and iron uptake were determined weekly by measuring depletion from the nutrient solutions. For ammonium uptake, 10 µL of the nutrient solution was taken from each sample bottle before the solutions were changed each week. One hundred microlitres of 175 mm Na2‐EDTA, 200 µL phenolnitroprusside (744 mm phenol and 1·14 mm nitroprusside) and 400 µL hypochlorite solution (0·37 m NaOH, 0·35 m Na2HPO4·7H2O and 1 % NaOCl) were added to the samples. The samples were incubated in a shaking water bath at 40 °C for 30 min before reading with a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV‐160, Japan) at 636 nm.

For nitrate uptake, 10 µL of the nutrient solution was taken from each sample bottle before the solutions were changed each week and diluted with 1·5 ml distilled water. Concentrated HCl (15 µL of 12·1 n) was added and samples were vortexed before reading with a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV‐160, Japan) at 210 nm.

Iron concentration left in the solution was determined using an atomic absorption spectrophotometer (Perkin Elmer 3030B, Norwalk, Connecticut, USA) with a hallow cathode lamp as a light source and air–acetylene flame.

Iron reductase activity

Root FCR activities were quantified every 2 weeks. Root tips (1 cm long) were cut, placed in a beaker filled with ice water and transferred to the laboratory. Roots were weighed and about 100 mg f. wt of tissue were placed in a test tube. Root tissue was rinsed in 0·2 mm CaSO4 for 5 min before transferring to 2 mL assay solution, containing 10 mm CaSO4, 5 mm MES (pH 5·5), 0·1 mm Fe‐EDTA and 0·3 mm sodiumbathophenanthroline disulfonic acid (Na2‐BPDS). One test tube with 2 mL assay solution without root tissue was used as a control. Samples and control tubes were incubated for 1 h in a shaking water bath at 3000 g and 23 °C in the dark. After incubation, a 1 mL aliquot from each tube was transferred into a cuvette and read with a spectrophotometer at 535 nm (Shimadzu UV‐160, Japan). The concentration of Fe(II)‐BPDS produced was calculated using the molar extinction coefficient of 22·14 mM cm–1 (Chaney et al., 1972).

Nitrate reductase activity

Root NR activities were quantified every 2 weeks. Root tips (1 cm long) were cut, placed in a beaker filled with ice water, and transferred to the laboratory. Roots were weighed and about 100 mg f. wt of tissue were placed in each test tube (two tubes per replicate per treatment). Two millilitres of assay solution, composed of 2 % 1‐propanol, 100 mm KH2PO4 (pH 7·5) and 30 mm KNO3 were added to each test tube. One tube per replicate per treatment was immediately filtered through Whatman No. 2 paper and used as the time 0 control. Samples were vacuum‐infiltrated for 5 min and incubated in a shaking water bath at 31 °C and 3000 g for 1 h in the dark. After incubation, the assay solution with roots was filtered and a 1 mL aliquot from each sample was removed to a new tube. One millilitre of sulfanilamide (1% w/v in 1·5 n HCl) and 1 mL N‐(1‐naphthyl)‐ethylenediaminedihydrochloride (0·02% w/v in 0·2 n HCl) were added. The samples were incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The absorbance at 540 nm was determined with a spectrophotometer (modified from Jaworski, 1971). Leaf NR activities were quantified periodically, using 100 mg f. wt of leaf tissue from recently matured leaves and the methodology described above.

Plant growth and harvesting

Plants were harvested on 20 June 2000, separated into shoots (stems and leaves) and roots, and the fresh weight of each part determined. Dry weight was determined after oven drying at 70 °C to constant weight. Removal of root tips (100 mg) for FCR and NR activity measurements did not appear to have any impact on root or plant growth, as this represented a small fraction (<0·05 %) of the total root fresh weight. Visual observations indicated that root tip number was not affected by treatments.

Experimental design

Treatments were arranged in a 2 × 2 × 2 factorial in a randomized complete block design with four replicates, using a single plant per replicate. The factors were plant species (V. corymbosum or V. arboreum), nitrogen forms [(NH4)2SO4 or NaNO3] and iron concentrations (0 or 90 µm). Data were analysed using SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Mean separation was performed using a t‐test on every pair of least square means (LSM). Daily nitrogen and iron uptake rates per plant and final fresh and dry weights were analysed using initial plant fresh weight as a covariate to normalize for differences in initial plant size.

RESULTS

Nitrogen uptake

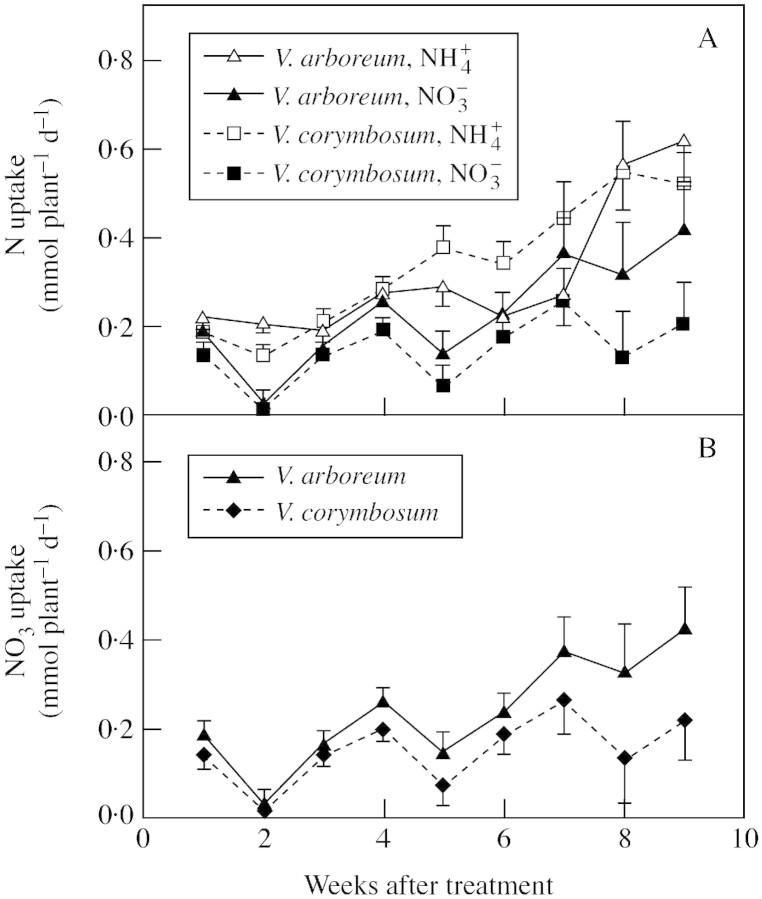

In general, the ammonium uptake rate was significantly higher than the nitrate uptake rate throughout the experiment, regardless of species (Fig. 1A). The average rates for ammonium uptake in both species ranged from 0·18 to 0·57 mmol NH4+ plant–1 d–1, while the uptake rates for nitrate ranged from 0·02 to 0·32 mmol NO3– plant–1 d–1. Throughout the experiment, nitrate uptake rates on a whole plant basis were greater in V. arboreum than in V. corymbosum, although significant differences were not manifested until 9 weeks after treatment (Fig. 1B). Only the beginning and ending time points for nitrate uptake could be normalized for differences in plant fresh weight increases, since these were the only times plant fresh weights were measured. The specific nitrate uptake rates for the beginning and end of the experiment were greater in V. arboreum than in V. corymbosum (16·3 vs. 10·1 nmol NO3 g–1 f. wt, respectively, at week 1, P < 0·10; and 27·2 vs. 14·9 nmol NO3 g–1 f. wt, respectively, at the end of the experiment, P < 0·05). Iron concentration did not significantly affect ammonium or nitrate uptake rate, regardless of species (data not shown).

Fig. 1. Interaction between species and nitrogen form on nitrogen uptake rate (A) and species effect on nitrate uptake rate (B). Iron levels had no significant effect on nitrogen uptake, thus data for the two iron levels are pooled. Values are adjusted means using initial whole plant fresh weight as a covariate. Mean ± SE (n = 4).

Nitrate reductase activity

Nitrate reductase activity was detected in root tissue throughout the experiment, with no activity found in leaf tissue. There was a significant interaction between species and nitrogen form on root NR activity (Fig. 2). Under nitrate conditions, NR activity in V. arboreum increased gradually from 240 to 540 nmol NO2– g–1 f. wt h–1; however, in V. corymbosum, NR activity decreased from week 3 (350 nmol NO2– g–1 f. wt h–1) until week 11 (170 nmol NO2– g–1 f. wt h–1). Under ammonium conditions, NR activity in both species in creased gradually from approx. 20 to 200 nmol NO2– g–1 f. wt h–1 throughout the experiment.

Fig. 2. Species and nitrogen form effect on root nitrate reductase (NR) activity. Mean ± SE (n = 4).

Iron concentration had a significant effect on root NR activity during the –Fe treatment period (Fig. 3). NR activity was greater under iron‐deficient compared with iron‐sufficient conditions at week 3. However, by week 5, NR activity under iron‐deficient conditions was lower than under iron‐sufficient conditions. When iron supply was resumed to –Fe plants at week 6, NR activities in these plants increased to rates similar to +Fe plants.

Fig. 3. Iron concentration effects on root nitrate reductase (NR) activity. 0 µm Fe preconditioning indicates the –Fe (0 µm) treatments after iron was resumed at week 6. There were no significant interactions between species and iron concentration on root nitrate reductase activity throughout the experiment, thus data are pooled for the two species. Mean ± SE (n = 4).

There were no interactions between species and iron concentration, or iron concentration and nitrogen form on root NR activity.

Iron uptake

There was no effect of species or nitrogen form on iron uptake. There was no iron uptake under iron‐deficient conditions, while the average iron uptake rate for iron‐sufficient plants was 2·3 µmol plant–1 d–1 throughout the experiment (data not shown). However, since much of the iron taken up by the plant roots may be precipitated as hydroxide or phosphate salts in the apoplast of roots, the actual amount of iron taken up by root cells is unknown and may comprise as little as 5 % of the total iron taken up (Hell and Stephan, 2003).

When iron (90 µm) was resumed after week 6 in plants that were in the –Fe treatment, there was a transient increase in iron uptake rate in V. corymbosum at week 7 compared with +Fe plants of the same species (4·4 vs. 3·6 µmol plant–1 d–1, respectively). After week 7, the iron uptake rate in previously treated –Fe V. corymbosum decreased to rates similar to +Fe plants. Again, however, the actual amount of iron taken up by root cells was not determined.

Root iron reductase activity

There was a significant interaction between species and iron concentration on root FCR. Under iron‐sufficient conditions, root FCR activity was similar between species, averaging approx. 200 nmol Fe2+ g–1 f. wt h–1 by week 1 after treatment, then decreasing to approx. 65 nmol Fe2+ g–1 f. wt h–1 by the end of the experiment (Fig. 4). This decrease in activity may be a result of iron released from the apoplast during measurements in +Fe plants. Under iron‐deficient conditions, root FCR activity in V. corymbosum increased from 150 to 400 nmol Fe2+ g–1 f. wt h–1 during the first 3 weeks after treatment, while activity in V. arboreum remained fairly constant throughout the experiment, averaging 70 nmol Fe2+ g–1 f. wt h–1. By week 5 after treatment, root FCR activity in V. corymbosum under iron‐deficient conditions decreased slightly, but was still significantly higher than activity in V. arboreum. When iron was resumed to –Fe V. corymbosum plants at week 6 after treatment, root FCR activity decreased to the same level as the +Fe plants.

Fig. 4. Interaction between species and iron concentration (0 or 90 µm) on root ferric chelate reductase (FCR) activity. Iron (90 µm) was resumed in iron‐deficient treatments (0 µm Fe) after week 6. Mean ± SE (n = 4).

There was no significant effect of nitrogen form on root FCR activity. There was no significant interaction between species and nitrogen form or nitrogen form and iron concentration on root FCR activity.

Plant growth

There was a significant interaction between species and nitrogen form on final shoot fresh weight and dry weight. Shoot fresh weight of nitrate‐treated V. arboreum was significantly greater than ammonium‐treated plants of the same species and either nitrate‐ or ammonium‐treated V. corymbosum (Table 1). Dry weights of shoots and whole plants were significantly greater in nitrate‐treated V. arboreum and ammonium‐treated plants of both species compared with nitrate‐treated V. corymbosum. There was no effect of species or nitrogen form on root fresh weight or dry weight.

Table 1.

Interaction between species and nitrogen form on final fresh weight and dry weight of shoot, root and whole plant (shoot + root)

| Fresh weight (g) | Dry weight (g) | |||||

| Species/N form | Shoot | Root | Plant | Shoot | Root | Plant |

| V. arboreum/NH4 | 26·9b | 15·8a | 43·7a | 14·6a | 2·8a | 17·4a |

| V. arboreum/NO3– | 49·5a | 23·8a | 72·9a | 20·2a | 4·6a | 24·7a |

| V. corymbosum/NH4+ | 24·0b | 21·2a | 45·4a | 14·1a | 4·0a | 18·2a |

| V. corymbosum/NO3– | 20·0b | 20·1a | 41·1a | 8·2b | 3·7a | 11·9b |

Values are adjusted means using initial whole fresh weight as a covariate (n = 4).

Mean separation within columns was performed using a t‐test on every pair of least square means.

Means with different letters are statistically different at P ≤ 0·10.

Shoot and whole plant dry weights were significantly greater in iron‐sufficient plants compared with iron‐deficient plants regardless of species or nitrogen form (data not shown). Shoot dry weights averaged 17·1 and 11·5 in iron‐sufficient vs. iron‐deficient plants, respectively. Whole plants dry weights averaged 21·1 and 15·1 in sufficient vs. deficient plants. Iron concentration had no effect on shoot or root fresh weight or root dry weight.

DISCUSSION

Vaccinium corymbosum and V. arboreum were able to take up both nitrate and ammonium; however, ammonium uptake rates were 1·7‐ to 8·5‐fold greater than nitrate uptake rates in both species. This agrees with previous work on cultivated Vaccinium species (Merhaut and Darnell, 1995). Higher rates of ammonium uptake may be related to the enzymatic pathways used for ammonium assimilation. Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) seedlings exhibited increased glutamine synthetase (GS) activity when fertilized with ammonium compared with nitrate (Seith et al., 1994). Differential regulation of two cytosolic GS isogenes by exogenous ammonium supply has been reported in grapevine (Suarez et al., 2002). However, Claussen and Lenz (1999) reported that nitrogen source (nitrate vs. ammonium) did not significantly affect root, stem, or leaf GS activity in sand‐cultured V. corymbosum. Regulation of other enzymes involved in ammonium assimilation in Vaccinium, e.g. glutamate synthase, has not been examined.

The lower rates of nitrate uptake in V. corymbosum may be related to activity of NR, which was markedly lower compared with V. arboreum and many other woody (Hucklesby and Blanke, 1987; Lee and Titus, 1992) and herbaceous plants (Hucklesby and Blanke, 1987). In general, root NR activity in other woody species is similar to or higher than activities measured in V. corymbosum, averaging 300 nmol NO2 g–1 f. wt h–1 in apple (Lee and Titus, 1992), 370 nmol NO2 g–1 f. wt h–1 in calamondin (Citrus madurensis) (Hucklesby and Blanke, 1987), and up to 800 nmol NO2 g–1 f. wt h–1 in oak (Thomas and Hilker, 2000). Additionally, leaf reduction of nitrate is common in woody plants, and many woody plants exhibit much higher leaf compared with root NR activity. Leaf NR activity in several woody crops, including strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa), raspberry (Rubus idaeus), apple and calamondin ranges from 800 to 2200 nmol NO2 g–1 f. wt h–1 (Hucklesby and Blanke, 1987; Lee and Titus, 1992; Claussen and Lenz, 1999). The lack of detectable leaf NR activity in V. corymbosum and V. arboreum found in the present study is supported by work with other cultivated and wild Vaccinium species (Smirnoff et al., 1984; Claussen and Lenz, 1999). The low root NR activity in V. corymbosum, coupled with lack of detectable leaf NR activity, could contribute to nitrogen deficiency and decreased growth on soils where the predominant nitrogen form is nitrate.

Although NR activity in Vaccinium is generally lower than in other plants, the average root NR activity in V. arboreum grown in nitrate was 1·5‐ to 3·2‐fold higher than V. corymbosum grown in nitrate. The higher root NR activity in V. arboreum was reflected in significant increases in specific nitrate uptake at the beginning and end of the experiment compared with V. corymbosum. It was also reflected in increased nitrate uptake on a whole plant basis at the end of the experiment.

Nitrate reductase is a complex enzyme that contains iron in one of its subunits (Crawford et al., 1992) and lack of iron can reduce NR activity (Marschner, 1995). In this present study, NR activity in iron‐deficient plants was greater in week 3 but lower in week 5 compared with iron‐sufficient plants. The greater NR activity in iron‐deficient plants at week 3 may reflect the ability of NR to compete with FCR for the electron provided by NAD(P)H, resulting in increased NR activity (Campbell and Redinbaugh, 1984). However, the reduction of NR activity by week 5 may be the result of a decrease in ferrodoxin, the electron donor for the NR, under iron deficiency (Marschner, 1995). The decrease in ferrodoxin may down‐regulate NR activity to prevent nitrite accumulation, which is toxic to the plant. The ferrodoxin content and NR activity are restored upon iron resupply (Marschner, 1995). The increase in NR activity after iron was resumed to nutrient solutions in the present experiment supports this idea.

Vaccinium corymbosum responded to iron deficiency by increased root FCR activity. Root FCR activity increased about 1·5‐ to 1·8‐fold under iron‐deficient conditions compared with iron‐sufficient conditions in V. corymbosum. The increased root FCR activity under iron deficiency in V. corymbosum is similar to the increases reported in peach (Prunus persica) (de la Guardia et al., 1995) and Citrus macrophylla rootstocks (Manthey et al., 1994) under iron‐deficient conditions. In contrast, root FCR activity in V. arboreum did not increase under iron deficiency.

The higher root FCR activity in V. corymbosum in response to iron deficiency was not reflected in increased iron uptake rate due to the lack of iron in the nutrient solution during the first 6 weeks of treatment. However, there was a significant increase in iron uptake rate in previously treated –Fe V. corymbosum after iron was resumed at week 7. Thus, iron availability in the solution was the limiting factor for iron uptake in the present experiment.

Although nitrogen form has been reported to affect FCR activity and iron uptake in several plant species, it appears to do so indirectly by affecting apoplastic pH (Kosegarten et al., 1999). The activity of FCR is pH dependent, with optimum pH ranging from 4·0 to 6·0 (Moog and Bruggemann, 1994). Uptake of ammonium by plant roots leads to acidification of the rhizosphere and apoplast, which would increase activity of FCR and lead to increased iron uptake (Marschner, 1995). By contrast, uptake of nitrate would result in alkalinization, decreasing FCR activity and iron uptake. In the present study, pH was held constant at 5·5 under both nitrogen forms, thus no effect of nitrogen form on FCR activity or iron uptake was observed.

The lower nitrate uptake rate compared with ammonium uptake rate was reflected in decreased plant dry weight in V. corymbosum grown under nitrate compared with ammonium. This result is in agreement with Merhaut (1993) and Claussen and Lenz (1999) in highbush blueberry. However, no difference in plant dry weight was observed in V. arboreum. The greater growth of V. arboreum compared with V. corymbosum under nitrate conditions indicates that V. arboreum may survive better than V. corymbosum in upland high pH soils, where nitrate is the predominant nitrogen form.

The results from the present study indicate that the wild species, V. arboreum, is more efficient in acquiring nitrate compared with the cultivated species, V. corymbosum. This is supported by the higher root NR activity in V. arboreum and increased nitrate uptake, which supports our hypothesis that this species is potentially more efficient than V. corymbosum in terms of nitrate reduction. However, it appears that V. corymbosum is potentially more efficient than V. arboreum in iron acquisition, as evidenced by increased root FCR activity under iron‐deficient conditions.

Thus, it appears that increased ability to utilize nitrate, and not increased efficiency of iron uptake, may play a role in the adaptation of V. arboreum to upland soils. The ability of V. arboreum to utilize nitrate more efficiently than V. corymbosum would be an advantage in upland, high pH soils, where nitrate is the predominant source of nitrogen. Although V. arboreum does not have economical value, it may be useful in Vaccinium breeding/genetic programmes as a source of soil adaptation for expansion of cultivated Vaccinium species. In addition, root NR activity may be useful as a screening tool for adaptation potential of Vaccinium genotypes to high pH soils.

Supplementary Material

Received: 24 July 2003; Returned for revision: 6 October 2003; Accepted: 12 December 2003; Published electronically: 23 February 2004

References

- Anon.2003. Are you in a wetland? www.nhdfl.org/publications/MAN07–13.pdf (13 Jan. 2003). [Google Scholar]

- BercziA, Moller IM.2000. Redox enzymes in the plant plasma membrane and their possible roles. Plant, Cell and Environment 23: 1287–1302. [Google Scholar]

- BrownJC, Draper AD.1980. Differential response of blueberry (Vaccinium) progenies to pH and subsequent use of iron. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 105: 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- CampbellWH, Redinbaugh MG.1984. Ferric‐citrate reductase activity of nitrate reductase and its role in iron assimilation by plants. Journal of Plant Nutrition 7: 799–806. [Google Scholar]

- ChaneyRL, Brown JC, Tiffin LO.1972. Obligatory reduction of ferric chelates in iron uptake by soybeans. Plant Physiology 50: 208–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ClaussenW, Lenz F.1999. Effect of ammonium or nitrate nutrition on net photosymthesis, growth, and activity of the enzymes nitrate reductase and glutamine synthetase in blueberry, raspberry and strawberry. Plant and Soil 208: 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- CrawfordNM.1995. Nitrate: nutrient and signal for plant growth. Plant Cell 7: 859–868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CrawfordNM, Wilkinson JQ, LaBrie ST.1992. Control of nitrate reduction in plants. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology 19: 377–385. [Google Scholar]

- CurieC, Briat J.2003. Iron transport and signaling in plants. Annual Review of Plant Biology 54: 183–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DasganHY, Romheld V, Cakmak I, Abak K.2002. Physiological root responses of iron deficiency susceptible and tolerant tomato genotypes and their reciprocal F1 hybrids. Plant and Soil 241: 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- delaGuardiaMD, Alcantara E.2002. A comparison of ferric‐chelate reductase and chlorophyll and growth ratios as indices of selection of quince, pear and olive genotypes under iron deficiency stress. Plant and Soil 241: 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- delaGuardiaMD, Filipe A, Alcantara E, Fournier JM, Romera FJ.1995. Evaluation of experimental peach rootstocks grown in nutrient solutions for tolerance to iron stress. In: Abadia J, ed. Iron nutrition in soils ands plants Amsterdam: Kluwer, 201–205. [Google Scholar]

- DirrMA, Barker AV, Maynard DN.1972. Nitrate reductase activity in the leaves of the highbush blueberry and other plants. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 97: 329–331. [Google Scholar]

- ErbWA, Draper AD, Swartz HJ.1993. Relation between moisture stress and mineral soil tolerance in blueberries. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 118: 130–134. [Google Scholar]

- HellR, Stephan UW.2003. Iron uptake, trafficking and homeostasis in plants. Planta 216: 541–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HucklesbyDP, Blanke MM.1987. Limitation of nitrogen assimilation in plants. I. Photosynthesis, nitrate content and distribution and pH‐optima of nitrate reductase in apple, citrus, cucumber, spinach and tomato. Gartenbauwissenschaft 52: 176–180. [Google Scholar]

- JaworskiEG.1971. Nitrate reductase assay in intact plant tissues. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 43: 1274–1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KorcakRF.1986. Adaptability of blueberry species to various soil types. I. Growth and initial fruiting. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 111: 816–821. [Google Scholar]

- KorcakRF.1987. Iron deficiency chlorosis. Horticultural Reviews 9: 133–185. [Google Scholar]

- KorcakRF.1988. Nutrition of blueberry and other calcifuges. Horticultural Reviews 10: 183–227. [Google Scholar]

- KorcakRF, Galletta GJ, Draper DA.1982. Response of blueberry seedlings to a range of soil types. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 107: 1153–1160. [Google Scholar]

- KosegartenH, Hoffmann B, Mengel K.1999. Apoplastic pH and Fe3+ reduction in intact sunflower leaves. Plant Physiology 121: 1069–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeeHJ, Titus JS.1992. Nitrogen accumulation and nitrate reductase activity in MM. 106 apple trees as affected by nitrate supply. Journal of Horticultural Science 67: 273–281. [Google Scholar]

- LyrenePM.1997. Value of various taxa in breeding tetraploid blueberries in Florida. Euphytica 94: 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- MantheyJA, McCoy DL, Crowley DE.1994. Stimulation of rhizosphere iron reduction and uptake in response to iron deficiency in citrus rootstocks. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 32: 211–215. [Google Scholar]

- MarschnerH.1995.Mineral nutrition of higher plants, 2nd edn. San Diego: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- MengelK.1994. Iron availability in plant tissues – iron chlorosis on calcareous soils. Plant and Soil 165: 275–283. [Google Scholar]

- MerhautDJ.1993.Effects of nitrogen form on vegetative growth, and carbon/nitrogen assimilation, metabolism, and partitioning in blueberry. PhD Dissertation, University of Florida, USA. [Google Scholar]

- MerhautDJ, Darnell RL.1995. Ammonium and nitrate accumulation in containerized southern highbush blueberry plants. HortScience 30: 1378–1381. [Google Scholar]

- MoogPR, Bruggemann W.1994. Iron reductase systems on the plant plasma membrane. A review. Plant and Soil 165: 241–260. [Google Scholar]

- PateJS.1980. Transport and partitioning of nitrogeneous solutes. Annual Review of Plant Physiology 31: 313–340. [Google Scholar]

- SchmidtW.1999. Review mechanisms and regulation of reduction‐based iron uptake in plants. New Phytologist 141: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- SeithMD, Setzer B, Flaig H, Mohr H.1994. Appearance of nitrate reductase, nitrite reductase and glutamine synthetase in different organs of the Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) seedling as affected by light, nitrate and ammonium. Physiologia Plantarum 91: 419–426. [Google Scholar]

- ShawSP, Fredine CG.1956.Wetlands of the United States – their extent and their value to waterfowl and other wildlife. US Department of the Interior, Washington, DC. Circular No. 39. [Google Scholar]

- SmirnoffN, Todd P, Stewart GR.1984. The occurrence of nitrate reduction in the leaves of woody plants. Annals of Botany 54: 363–374. [Google Scholar]

- SpiersJM.1978. Effects of pH levels and nitrogen source on elemental leaf content of Tifblue rabbiteye blueberry. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 103: 705–708. [Google Scholar]

- SuarezMF, Avila C, Gallardo F, Canton FR, Garcia‐Gutierrez A, Claros MG, Canovas FM.2002. Molecular and enzymatic analysis of ammonium assimilation in woody plants. Journal of Experimental Botany 53: 891–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ThomasFM, Hilker C.2000. Nitrate reduction in leaves and roots of young pedunculate oaks (Quercus robur) growing on different nitrate concentrations. Environmental and Experimental Botany 43: 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- TownsendLR.1970. Effect of form of N and pH on nitrate reductase activity in lowbush blueberry leaves and roots. Canadian Journal of Plant Science 50: 603–605. [Google Scholar]

- WilliamsonJW, Lyrene PM.1998.Florida’s Commercial Blueberry Industry. Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida, Publication HS 742. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.