Abstract

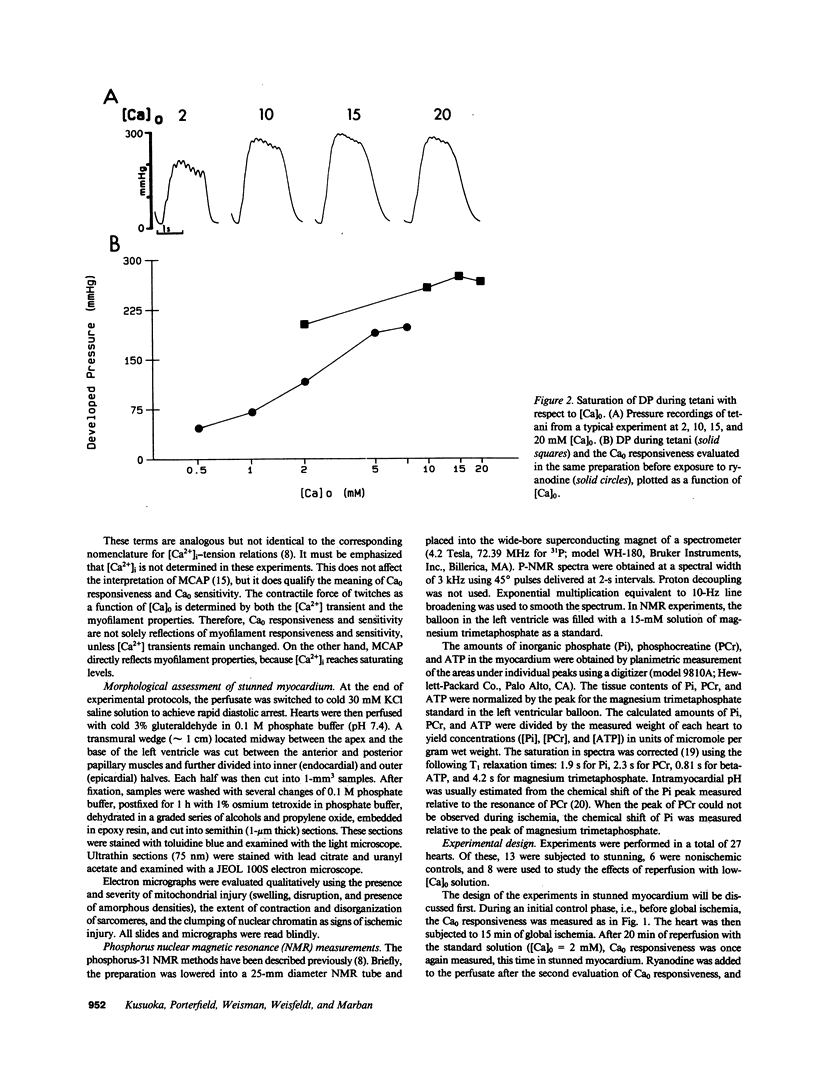

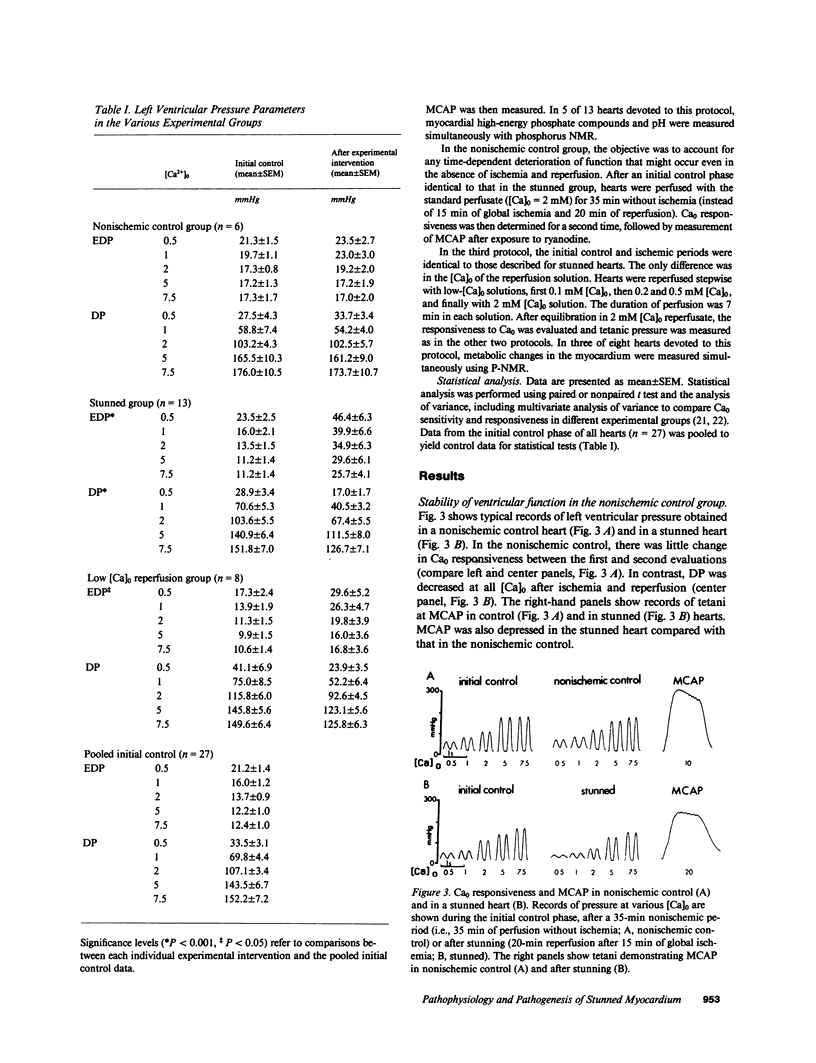

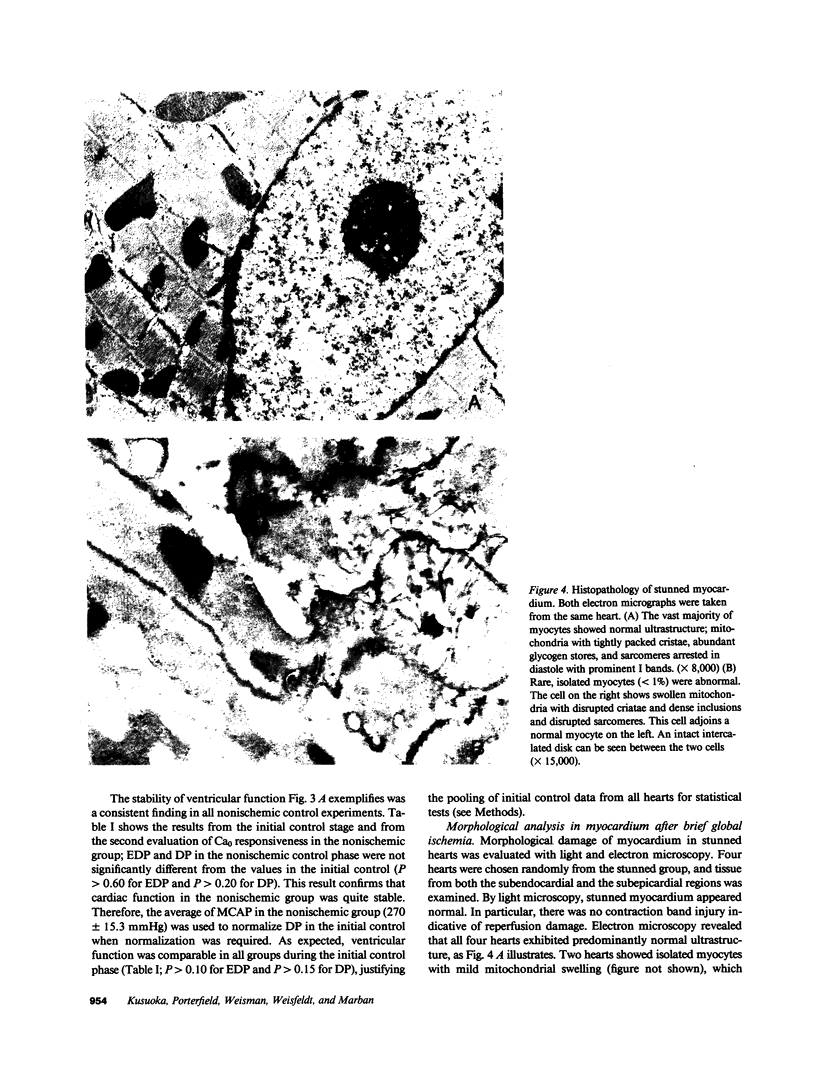

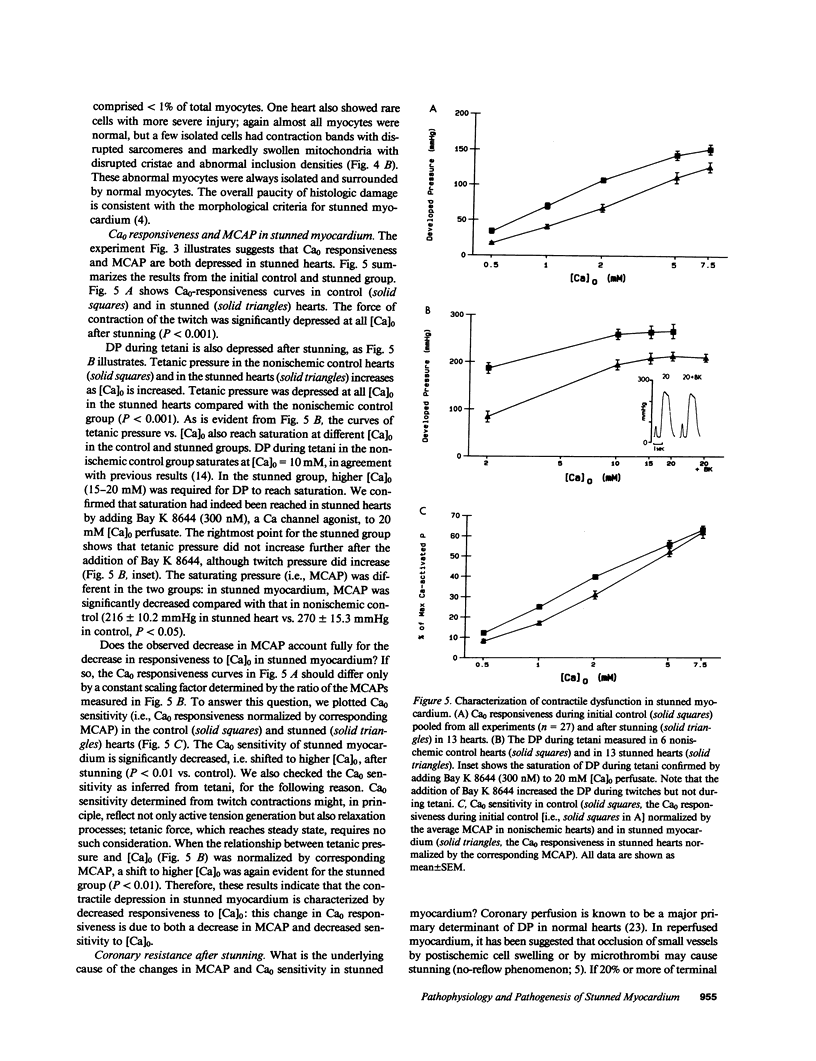

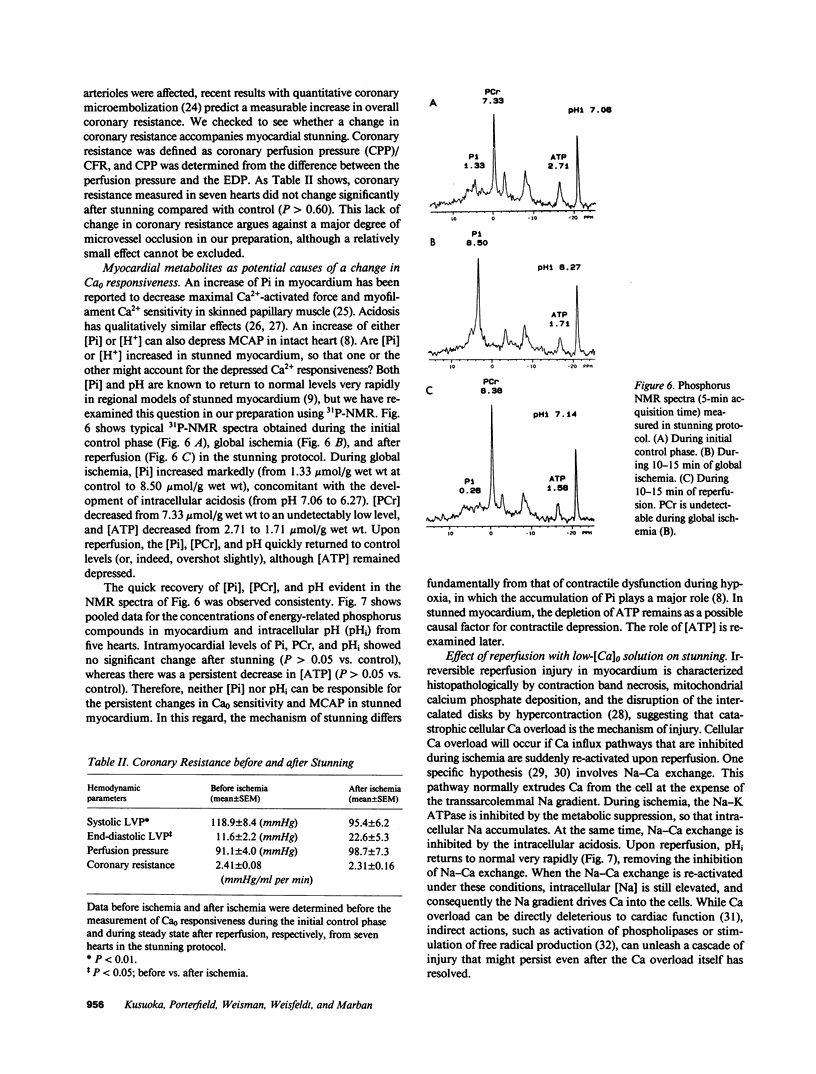

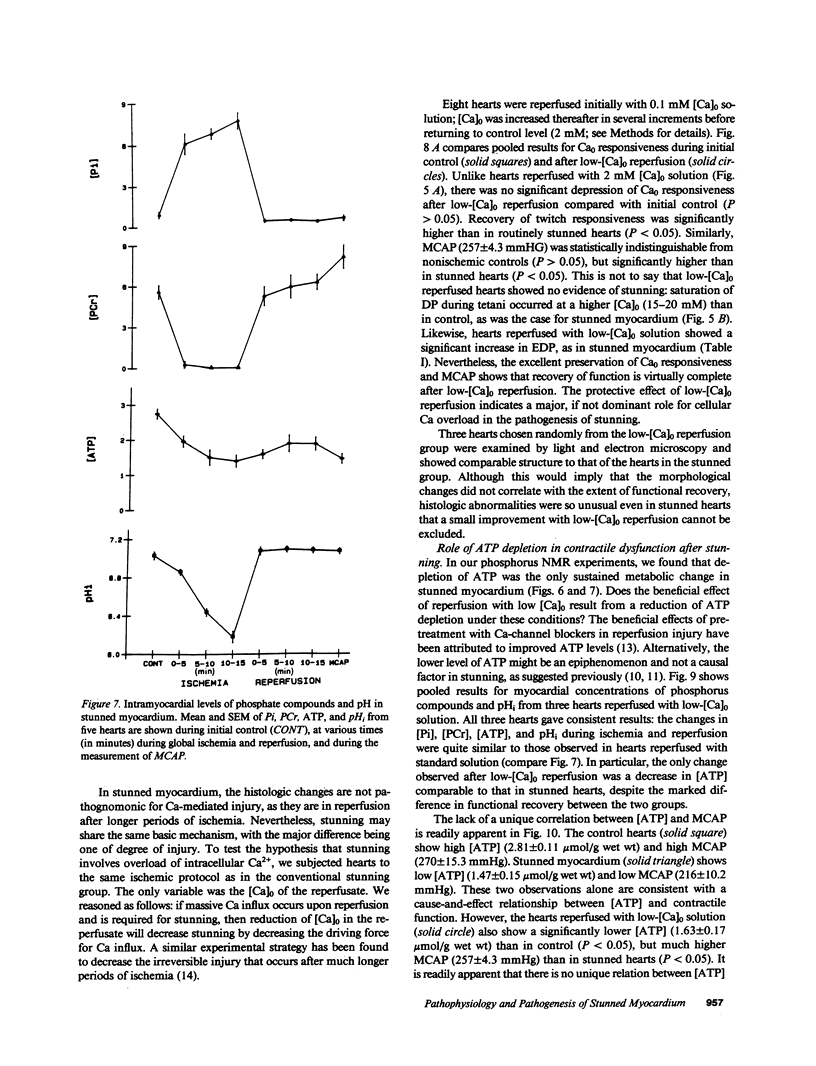

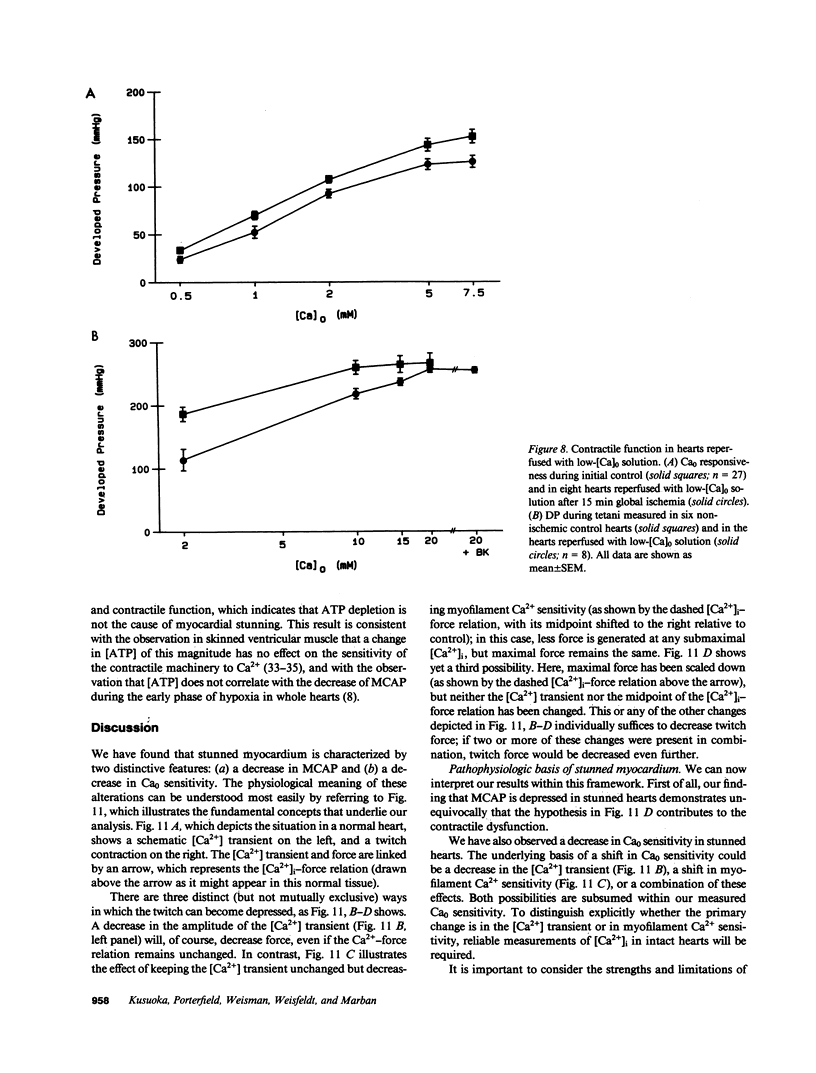

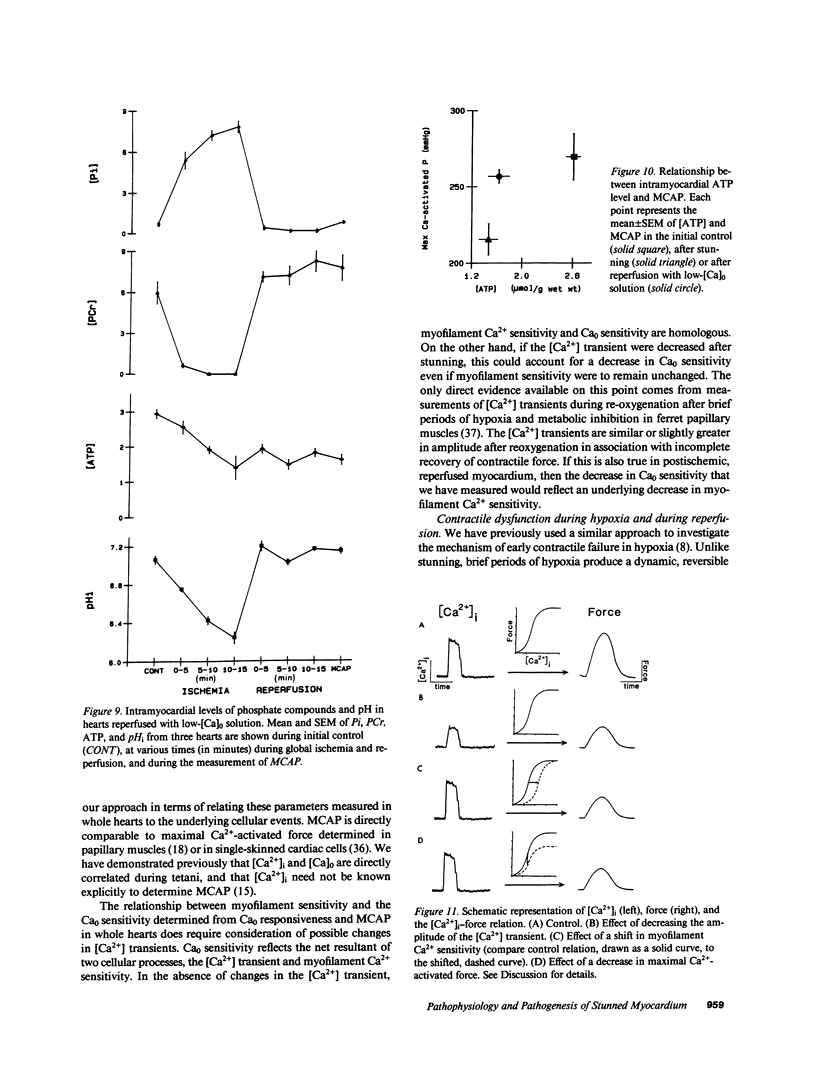

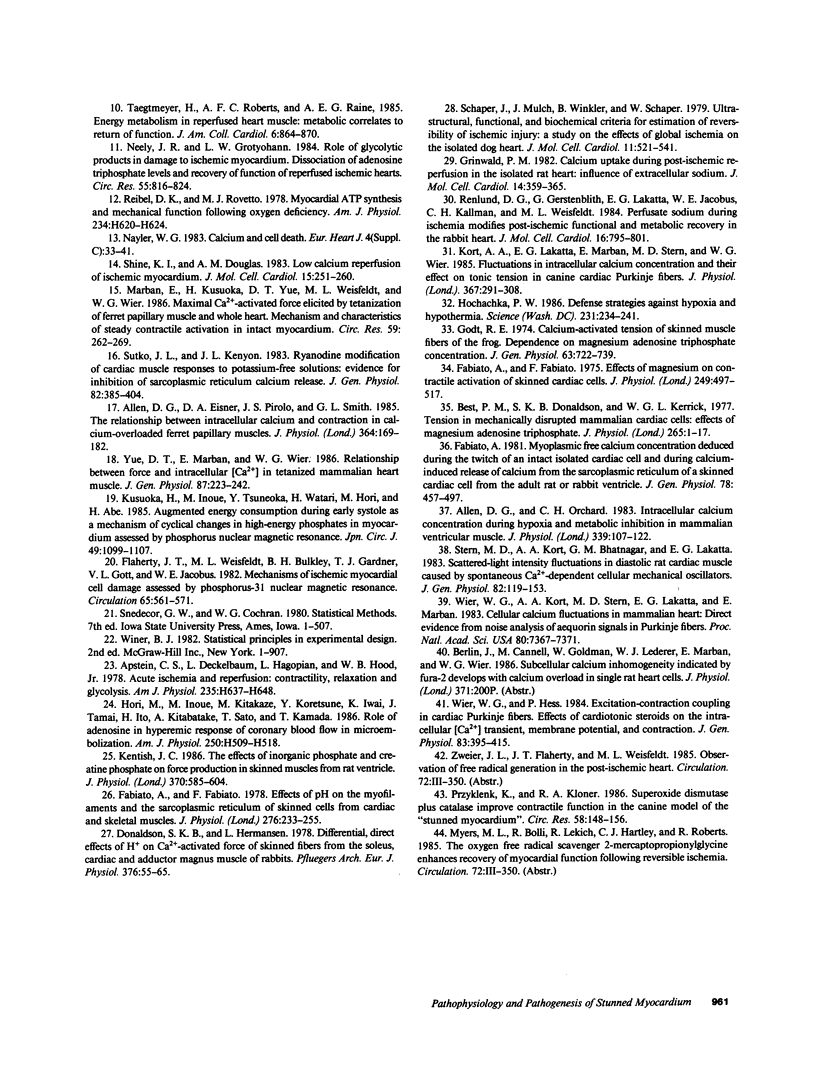

Contractile dysfunction in stunned myocardium could result from a decrease in the intracellular free [Ca2+] transient during each beat, a decrease in maximal Ca2+-activated force, or a shift in myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity. We measured developed pressure (DP) at several [Ca]0 (0.5-7.5 mM) in isovolumic Langendorff-perfused ferret hearts at 37 degrees C after 15 min of global ischemia (stunned group, n = 13) or in a nonischemic control group (n = 6). At all [Ca]0, DP was depressed in the stunned group (P less than 0.001). Maximal Ca2+-activated pressure (MCAP), measured from tetani after exposure to ryanodine, was decreased after stunning (P less than 0.05). Normalization of the DP-[Ca]0 relationship by corresponding MCAP (Ca0 sensitivity) revealed a shift to higher [Ca]0 in stunned hearts. To test whether cellular Ca overload initiates stunning, we reperfused with low-[Ca]0 solution (0.1-0.5 mM; n = 8). DP and MCAP in the low-[Ca]0 group were comparable to control (P greater than 0.05), and higher than in the stunned group (P less than 0.05). Myocardial [ATP] observed by phosphorus NMR failed to correlate with functional recovery. In conclusion, contractile dysfunction in stunned myocardium is due to a decline in maximal force, and a shift in Ca0 sensitivity (which may reflect either decreased myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity or a decrease in the [Ca2+] transient). Our results also indicate that calcium entry upon reperfusion plays a major role in the pathogenesis of myocardial stunning.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Allen D. G., Eisner D. A., Pirolo J. S., Smith G. L. The relationship between intracellular calcium and contraction in calcium-overloaded ferret papillary muscles. J Physiol. 1985 Jul;364:169–182. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen D. G., Orchard C. H. Intracellular calcium concentration during hypoxia and metabolic inhibition in mammalian ventricular muscle. J Physiol. 1983 Jun;339:107–122. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apstein C. S., Deckelbaum L., Hagopian L., Hood W. B., Jr Acute cardiac ischemia and reperfusion: contractility, relaxation, and glycolysis. Am J Physiol. 1978 Dec;235(6):H637–H648. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1978.235.6.H637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker L. C., Levine J. H., DiPaula A. F., Guarnieri T., Aversano T. Reversal of dysfunction in postischemic stunned myocardium by epinephrine and postextrasystolic potentiation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986 Mar;7(3):580–589. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(86)80468-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best P. M., Donaldson S. K., Kerrick W. G. Tension in mechanically disrupted mammalian cardiac cells: effects of magnesium adenosine triphosphate. J Physiol. 1977 Feb;265(1):1–17. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp011702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braunwald E., Kloner R. A. Myocardial reperfusion: a double-edged sword? J Clin Invest. 1985 Nov;76(5):1713–1719. doi: 10.1172/JCI112160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braunwald E., Kloner R. A. The stunned myocardium: prolonged, postischemic ventricular dysfunction. Circulation. 1982 Dec;66(6):1146–1149. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.66.6.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciuffo A. A., Ouyang P., Becker L. C., Levin L., Weisfeldt M. L. Reduction of sympathetic inotropic response after ischemia in dogs. Contributor to stunned myocardium. J Clin Invest. 1985 May;75(5):1504–1509. doi: 10.1172/JCI111854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson S. K., Hermansen L., Bolles L. Differential, direct effects of H+ on Ca2+ -activated force of skinned fibers from the soleus, cardiac and adductor magnus muscles of rabbits. Pflugers Arch. 1978 Aug 25;376(1):55–65. doi: 10.1007/BF00585248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiato A., Fabiato F. Effects of magnesium on contractile activation of skinned cardiac cells. J Physiol. 1975 Aug;249(3):497–517. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1975.sp011027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiato A., Fabiato F. Effects of pH on the myofilaments and the sarcoplasmic reticulum of skinned cells from cardiace and skeletal muscles. J Physiol. 1978 Mar;276:233–255. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiato A. Myoplasmic free calcium concentration reached during the twitch of an intact isolated cardiac cell and during calcium-induced release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum of a skinned cardiac cell from the adult rat or rabbit ventricle. J Gen Physiol. 1981 Nov;78(5):457–497. doi: 10.1085/jgp.78.5.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty J. T., Weisfeldt M. L., Bulkley B. H., Gardner T. J., Gott V. L., Jacobus W. E. Mechanisms of ischemic myocardial cell damage assessed by phosphorus-31 nuclear magnetic resonance. Circulation. 1982 Mar;65(3):561–570. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.65.3.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godt R. E. Calcium-activated tension of skinned muscle fibers of the frog. Dependence on magnesium adenosine triphosphate concentration. J Gen Physiol. 1974 Jun;63(6):722–739. doi: 10.1085/jgp.63.6.722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinwald P. M. Calcium uptake during post-ischemic reperfusion in the isolated rat heart: influence of extracellular sodium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1982 Jun;14(6):359–365. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(82)90251-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochachka P. W. Defense strategies against hypoxia and hypothermia. Science. 1986 Jan 17;231(4735):234–241. doi: 10.1126/science.2417316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori M., Inoue M., Kitakaze M., Koretsune Y., Iwai K., Tamai J., Ito H., Kitabatake A., Sato T., Kamada T. Role of adenosine in hyperemic response of coronary blood flow in microembolization. Am J Physiol. 1986 Mar;250(3 Pt 2):H509–H518. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1986.250.3.H509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings R. B. Early phase of myocardial ischemic injury and infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1969 Dec;24(6):753–765. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(69)90464-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kentish J. C. The effects of inorganic phosphate and creatine phosphate on force production in skinned muscles from rat ventricle. J Physiol. 1986 Jan;370:585–604. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp015952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloner R. A., DeBoer L. W., Darsee J. R., Ingwall J. S., Hale S., Tumas J., Braunwald E. Prolonged abnormalities of myocardium salvaged by reperfusion. Am J Physiol. 1981 Oct;241(4):H591–H599. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1981.241.4.H591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloner R. A., Ellis S. G., Carlson N. V., Braunwald E. Coronary reperfusion for the treatment of acute myocardial infarction: postischemic ventricular dysfunction. Cardiology. 1983;70(5):233–246. doi: 10.1159/000173600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kort A. A., Lakatta E. G., Marban E., Stern M. D., Wier W. G. Fluctuations in intracellular calcium concentration and their effect on tonic tension in canine cardiac Purkinje fibres. J Physiol. 1985 Oct;367:291–308. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusuoka H., Inoue M., Tsuneoka Y., Watari H., Hori M., Abe H. Augmented energy consumption during early systole as a mechanism of cyclical changes in high-energy phosphates in myocardium assessed by phosphorus nuclear magnetic resonance. Jpn Circ J. 1985 Oct;49(10):1099–1107. doi: 10.1253/jcj.49.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusuoka H., Weisfeldt M. L., Zweier J. L., Jacobus W. E., Marban E. Mechanism of early contractile failure during hypoxia in intact ferret heart: evidence for modulation of maximal Ca2+-activated force by inorganic phosphate. Circ Res. 1986 Sep;59(3):270–282. doi: 10.1161/01.res.59.3.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marban E., Kusuoka H., Yue D. T., Weisfeldt M. L., Wier W. G. Maximal Ca2+-activated force elicited by tetanization of ferret papillary muscle and whole heart: mechanism and characteristics of steady contractile activation in intact myocardium. Circ Res. 1986 Sep;59(3):262–269. doi: 10.1161/01.res.59.3.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayler W. G. Calcium and cell death. Eur Heart J. 1983 May;4 (Suppl 100):33–41. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/4.suppl_c.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neely J. R., Grotyohann L. W. Role of glycolytic products in damage to ischemic myocardium. Dissociation of adenosine triphosphate levels and recovery of function of reperfused ischemic hearts. Circ Res. 1984 Dec;55(6):816–824. doi: 10.1161/01.res.55.6.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przyklenk K., Kloner R. A. Superoxide dismutase plus catalase improve contractile function in the canine model of the "stunned myocardium". Circ Res. 1986 Jan;58(1):148–156. doi: 10.1161/01.res.58.1.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reibel D. K., Rovetto M. J. Myocardial ATP synthesis and mechanical function following oxygen deficiency. Am J Physiol. 1978 May;234(5):H620–H624. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1978.234.5.H620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renlund D. G., Gerstenblith G., Lakatta E. G., Jacobus W. E., Kallman C. H., Weisfeldt M. L. Perfusate sodium during ischemia modifies post-ischemic functional and metabolic recovery in the rabbit heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1984 Sep;16(9):795–801. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(84)80003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaper J., Mulch J., Winkler B., Schaper W. Ultrastructural, functional, and biochemical criteria for estimation of reversibility of ischemic injury: a study on the effects of global ischemia on the isolated dog heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1979 Jun;11(6):521–541. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(79)90428-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shine K. I., Douglas A. M. Low calcium reperfusion of ischemic myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1983 Apr;15(4):251–260. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(83)90280-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern M. D., Kort A. A., Bhatnagar G. M., Lakatta E. G. Scattered-light intensity fluctuations in diastolic rat cardiac muscle caused by spontaneous Ca++-dependent cellular mechanical oscillations. J Gen Physiol. 1983 Jul;82(1):119–153. doi: 10.1085/jgp.82.1.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutko J. L., Kenyon J. L. Ryanodine modification of cardiac muscle responses to potassium-free solutions. Evidence for inhibition of sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release. J Gen Physiol. 1983 Sep;82(3):385–404. doi: 10.1085/jgp.82.3.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taegtmeyer H., Roberts A. F., Raine A. E. Energy metabolism in reperfused heart muscle: metabolic correlates to return of function. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1985 Oct;6(4):864–870. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(85)80496-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner J. M., Astein C. S., Arthur J. H., Pirzada F. A., Hood W. B., Jr Persistence of myocardial injury following brief periods of coronary occlusion. Cardiovasc Res. 1976 Nov;10(6):678–686. doi: 10.1093/cvr/10.6.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wier W. G., Hess P. Excitation-contraction coupling in cardiac Purkinje fibers. Effects of cardiotonic steroids on the intracellular [Ca2+] transient, membrane potential, and contraction. J Gen Physiol. 1984 Mar;83(3):395–415. doi: 10.1085/jgp.83.3.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wier W. G., Kort A. A., Stern M. D., Lakatta E. G., Marban E. Cellular calcium fluctuations in mammalian heart: direct evidence from noise analysis of aequorin signals in Purkinje fibers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983 Dec;80(23):7367–7371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.23.7367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue D. T., Marban E., Wier W. G. Relationship between force and intracellular [Ca2+] in tetanized mammalian heart muscle. J Gen Physiol. 1986 Feb;87(2):223–242. doi: 10.1085/jgp.87.2.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]