Abstract

We describe a novel inherited disorder consisting of idiopathic massive splenomegaly, cytopenias, anhidrosis, chronic optic nerve edema, and vision loss. This disorder involves three affected patients in a single non-consanguineous Caucasian family, a mother and two daughters, who are half-sisters. All three patients have had splenectomies; histopathology revealed congestion of the red pulp, but otherwise no abnormalities. Electron microscopic studies of splenic tissue showed no evidence for a storage disorder or other ultrastructural abnormality. Two of the three patients had bone marrow examinations that were non-diagnostic. All three patients developed progressive vision loss such that the two oldest patients are now blind, possibly due to a cone-rod dystrophy. Characteristics of vision loss in this family include early chronic optic nerve edema, and progressive vision loss, particularly central and color vision. Despite numerous medical and ophthalmic evaluations, no diagnosis has been discovered.

Keywords: splenomegaly, vision loss, pancytopenia, optic nerve edema, cone-rod dystrophy

INTRODUCTION

Splenomegaly is a common feature of many hematologic and other disorders. The causes of splenomegaly include immune-mediated hypertrophy, hemolysis, congestion, myeloproliferation, infiltration, and neoplasia. We describe a novel inherited disorder in a mother and two daughters, each with idiopathic massive splenomegaly, cytopenias, migraine headaches, anhidrosis, chronic optic nerve edema, and vision loss. To our knowledge, no reports of a similar syndrome exist in the literature.

CLINICAL REPORTS

Case 1, an 18-year-old female [Patient III-2 in the pedigree, (Fig. 1)] presented with massive splenomegaly at 13 weeks gestation for evaluation of possible splenectomy due to concern for spontaneous rupture of the spleen. The patient presented with abdominal pain and splenic enlargement at 12 years of age. She denied recurrent infections, fever, chills, night sweats, weight loss, and bleeding manifestations. She reported anhidrosis, episodic urticaria, and recurrent migraine headaches. Laboratory tests then revealed mild pancytopenia with white blood cell count (WBC) count 2,700/μl, hemoglobin 8.9 g/dl, hematocrit 26%, and platelet count 96,000/μl. Her peripheral blood smear showed leukopenia with reactive lymphocytosis and mild thrombocytopenia. Bone marrow examination then showed normocellular bone marrow with trilineage hematopoiesis and relative erythroid hyperplasia. The patient reported chronic left upper quadrant pain.

FIG. 1.

Family tree: Case 1 is Patient III-2 in the pedigree; Case 2 (the mother) is Patient II-3 in the pedigree; and Case 3 (half-sister) is Patient III-1 in the pedigree.

The patient had also been evaluated by a pediatric ophthalmologist at the age of 8 years for decreased vision. Her initial ophthalmic examination at age 8 showed distance visual acuity of 20/20 in the right eye (OD) and 20/30 +2 in the left eye (OS). Color vision, pupils, and visual fields were normal. Slit lamp and fundus exam showed moderate, chronic optic disc edema, but was otherwise unremarkable.

She was seen 3 years later, at age 11 with intermittent, left sided or bitemporal headaches associated with photosensitivity and nausea. Visual acuity was correctable to 20/20 OD and 20/25 OS with no afferent pupillary defect. Color vision, which was previously normal, had now decreased to 2/7 Hardy Rand Rittlers (HRR) color plates with each eye. Visual field testing showed an enlarged blind spot. Slit lamp and fundus examination were normal except for mild lenticular changes and continued optic nerve edema. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain was normal. Optic nerve and retinal antibody tests were weakly positive and non-specific, consistent with non-autoimmune inflammation. No specific ophthalmologic diagnosis was made.

Continued follow-up showed deteriorating visual acuity of 20/ 200 OD, 20/200 OS at age 14 years with absent color vision on HRR color plate testing. She continued to have normal pupil exam and anterior slit lamp exam. Dilated exam showed continued optic nerve edema, now with peripapillary splinter hemorrhages. Humphrey visual field testing demonstrated bilateral cecocentral scotomas. Full-field electroretinography (ERG) showed severe flattening. At age 19, her visual acuity was 20/50 OD, 20/150 OS with continued absent color vision and normal pupils. Slit lamp exam showed quiet anterior chamber and no abnormalities. Dilated fundus exam demonstrated persistence of optic nerve edema with splinter hemorrhages and macular pigmentary changes.

Laboratory results from hematology clinic during pregnancy revealed: WBC 1,810/μl, hemoglobin 9.7 g/dl, hematocrit 27%, mean corpuscular volume (MCV) 74 fL, platelet count 94,000/μl. White cell differential count showed granulocytes 57%, lymphocytes 38%, and monocytes 3%. The peripheral blood smear showed normochromic, microcytic anemia, and mild thrombocytopenia. Renal function tests and liver function tests were normal. Ferritin level was low at 33 ng/dl.

The patient had an uncomplicated pregnancy and delivered a healthy male child. In 2010, the patient underwent splenectomy for symptomatic relief of pain. Repeat vision exam showed progressive vision loss.

Case 2, the proposita’s mother [Patient II-3 in the pedigree], was age 43 at the time of writing. She presented at age 10 to the pediatric ophthalmology clinic with gradual onset of vision loss and optic nerve edema. Visual acuity testing at presentation was 20/30 OD and 20/40 OS. Fundoscopy showed maculopathy and 1+cell in the anterior chamber. Few peripapillary flame hemorrhages were seen. There was no snowbanking in the pars plana.

Her vision declined over the next year to 20/30 OD and 20/200 OS. Fundoscopy showed flame hemorrhages at the disc and macula with preretinal fibrosis. Complete blood counts, sedimentation rate, renal and liver function tests were all normal. Antinuclear and anti-DNA antibodies were negative. Serology for toxoplasmosis, complement fixation test for histoplasmosis, blastomycosis and coccidoidomycosis were also negative. Chest X ray was normal. Lumbar puncture studies were normal with an opening pressure of 130 mm, WBC 3, no red cells; CSF protein and glucose were normal. Fluorescein retinal angiography showed optic disc edema, retinal edema, and cystoid macular edema. There were no focal chorioretinal lesions and no snowbanking exudates. She was treated with subtenon injections of steroids and topical steroid eye drops without significant improvement. She developed polyarthralgia and was evaluated further for autoimmune disease. Repeat antinuclear antibody (ANA) tests and HLA-B27 studies were negative, and there was no evidence of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. There was no evidence of ocular autoimmunity on immune tests utilizing purified retinal extracts, myelin basic protein and crude ocular extract. Ultrasound of orbits, computed tomographic imaging of the head and orbits, and sedimentation rate were all normal. ERGs showed slightly increased cone thresholds, but were otherwise within normal limits.

She continued to have vision loss and at age 13 pars plana vitrectomy was performed in left eye. Cytopathology of the vitreous showed chronic inflammatory cells and no clear etiology for uveitis or vision loss was identified. Vision loss progressed despite treatment at various times with intravitreal, subtenons, topical and oral steroids. The patient suffered continuing decline in visual function in her early twenties (20/300 OD and counting fingers OS) with an afferent pupillary defect OS. Exam showed severe retinal degeneration. Humphrey visual fields were severely constricted. At age 24 she had cataract surgery. She failed to respond to azathioprine therapy. By age 30 her vision had declined to counting fingers OD and hand motions OS.

In addition to her ophthalmic symptoms, at the age of 15, she developed epigastric discomfort and examination revealed splenomegaly which was confirmed by ultrasound. Blood counts showed mild neutropenia and thrombocytopenia. White cell differential counts showed 39% neutrophils, 55% lymphocytes, 5% monocytes, and 1% eosinophils. Peripheral blood smear showed occasional atypical lymphocytes. Repeat ANA testing was normal and infectious mononucleosis screen showed elevated Epstein–Barr virus titers (1:640). At the age of 19, she became pregnant and was noted to have massive splenomegaly to the level of umbilicus. She was referred to hematology clinic for further evaluation. Complete blood counts then showed WBC 4,900/μl, hemoglobin 12 g/dl, hematocrit 35%, MCV 84 fL, and platelet count 170,000/μl. Bone marrow biopsy was performed which showed mild erythroid hyperplasia. No Gaucher cells were identified in the bone marrow. Osmotic fragility test was normal as was hemoglobin electrophoresis. She delivered a healthy baby girl in 1987. In 1989 she became pregnant again and because of increasing abdominal pain she underwent elective splenectomy. Histological examination of spleen demonstrated features of congestive splenomegaly with marked congestion of the red pulp cords and sinuses and decreased white pulp consisting of non-reactive, morphologically normal lymphoid follicles. Scattered megakaryocytes were present, but significant extramedullary hematopoiesis was not seen. No granulomas or malignant infiltrates were identified. Histological examination of the hilar lymph nodes was normal. Complete blood count (CBC) indices were improved post-splenectomy.

Case 3, the third affected patient, [Patient III-1 in the pedigree] is the half-sister of the patient initially described. She presented at the age of 4 years with headaches and was noted to have marked disc swelling. Brain MRI was unremarkable. Lumbar puncture was normal, without elevated pressure. By age 7, vision was 20/400 OD and count fingers OS. Pattern visual evoked potentials were poor; however, ERGs were relatively normal with the exception of prolonged photopic b-wave implicit times. Dilated examination of her eyes showed pale, swollen discs with marked attenuation and sheathing of the vessels, very similar to her mother’s examination. Immunological studies including ANA, rheumatoid factor, and anti-DNA antibodies were normal. By 9 years of age, she had developed massive splenomegaly with abdominal discomfort and pancytopenia. She also had chronic, recurrent, intermittent migraine headaches, and anhidrosis. Splenectomy was performed at the age of 9. The spleen weighed 786 g (normal adolescent spleen weight is 100–200 g). Preoperative CBC showed WBC 2,600/μl, hematocrit 34%, and platelet count of 100,000/μl. Pathology of the spleen showed marked expansion of red pulp due to congestion of sinuses and cords with macrophage hyperplasia. Flow cytometry of the spleen was unremarkable. Microscopy of hilar lymph nodes demonstrated sinus histiocytosis and dilated sinuses.

Following splenectomy she continued to have progressive vision loss. By age 15, she was having intermittent headaches associated with transient monocular blindness. Ophthalmic exam showed visual acuity at distance to be 20/300 OD, 1/200 OS with color vision 0/7 HRR plates OU and a 1.2 log unit afferent pupillary defect OS. She continued to have bilateral optic nerve edema without elevated intracranial pressure on repeat lumbar puncture. Optic nerves were pale OU. Humphrey visual field examination disclosed central scotomas bilaterally with marked constriction of the visual fields. Full field ERGs showed absent photopic and scotopic responses. Pattern visual evoked potentials were absent, but flash evoked potential remained near normal. Ocular hypersensitivity tests with bovine retina and optic nerve failed to show any evidence of autoimmune reactivity against the retina or optic nerve.

At age 17, she was found to have 20/400 OD and hand motions OS. Lumbar puncture was again normal, without elevated pressure. Humphrey visual field showed central scotomas, marked visual field constriction and mid-peripheral scotomas bilaterally. Dilated fundus exam showed posterior vitreous detachment OD and trace cell stuck onto vitreous fibrils. Pallor of optic disc, and grade 1 optic nerve edema were present in both eyes with vessel attenuation. The foveal reflex was dull and retinal pigment epithelium alterations were present without frank spiculization. At age 19, she developed phacomorphic glaucoma with angle closure and was successfully treated with peripheral iridotomy and cataract surgery. By age 20, her visual acuity had declined to light perception OD and OS. Her exam at that time included mild vitreous cell and optic nerve pallor. Despite intraocular pressures of 8 mm Hg OD and 6 mm Hg OS, she was experiencing significant ocular pain.

All affected individuals were from nonconsanguineous unions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Electron microscopy was performed on freshly obtained splenic tissue from patient III-2, and on tissue obtained from a paraffin block of splenic tissue from Patient II-3. Both samples were processed and examined by standard transmission electron microscopic techniques.

RESULTS

Electron microscopic results revealed only red pulp expansion and congestion in splenic tissue obtained either freshly from the splenectomy specimen or from the paraffin block. There was no evidence for a lysosomal storage disorder or other ultrastructural abnormality seen in either patient’s spleen (II-3, III-2).

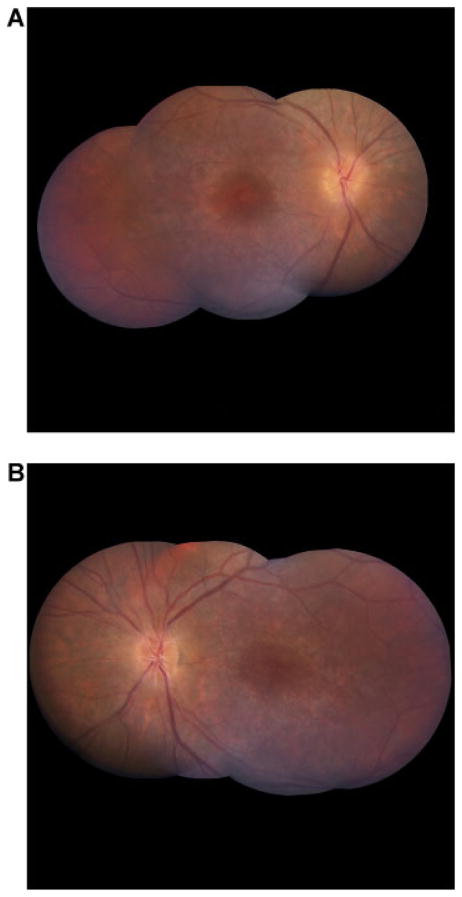

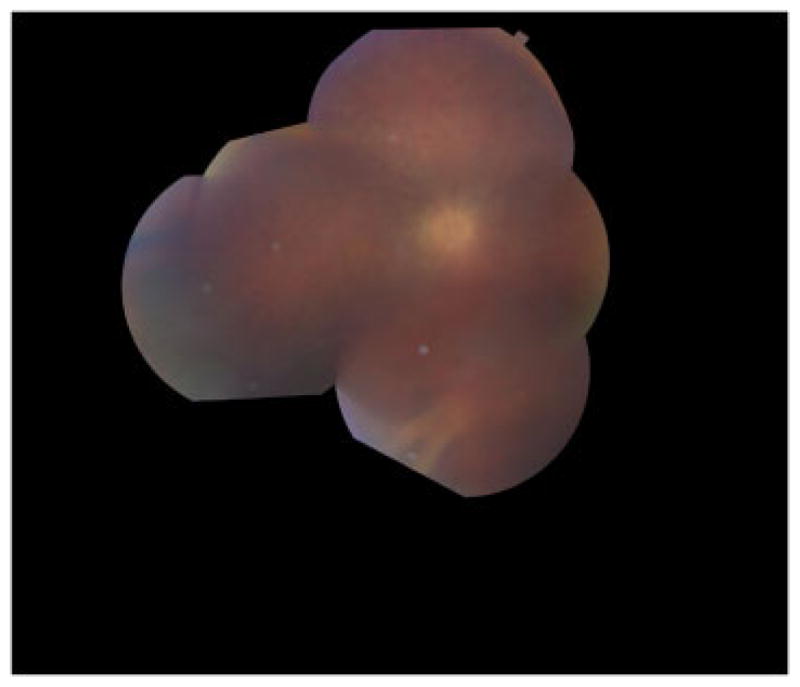

Figure 2A,B show fundus photographs of Patient III-2 at age 20, illustrating optic disk edema, flame hemorrhages, and attenuated blood vessels. Figure 3 shows fundus photographs of Patient III-1 at age 24 showing marked attenuation of retinal vessels and optic nerve pallor. Figure 4 shows ERG findings of Patient III-2 at ages 7 and 15, illustrating mildly diminished oscillatory potentials at age 7, progressing to marked attenuation by age 15. Figure 5 shows a multifocal ERG from Patient III-2 at age 13 (top) showing severe cone depression in the macula. The lower portion of the figure depicts a normal field for comparison. Figure 6 is a fluorescein angiogram from patient III-2 at age 14 demonstrating leakage from the optic nerve, but no vasculitis or cystoid macular edema.

FIG. 2.

Representative fundus photos and optic disc photo from this cohort. Shown are fundus photos of Patient III-2. A: Fundus montage photo of the right eye. B: Fundus montage photo of left eye of Patient III-2 at age 20. At the time of the photos, best corrected vision was 20/50 OD, and 20/150 OS. These photographs are representative of the other affected family members. Note: Optic disc edema, flame hemorrhages, and attenuated blood vessels.

FIG. 3.

Fundus montage photo from the left eye of patient III-1 at age 24. Her vision at this time was light perception only. Opacities and inflammation in the anterior chamber, lens capsule, and vitreous limit the view of the fundus. There is marked attenuation of retinal vessels, particularly arterioles, and optic nerve pallor.

FIG. 4.

ERG findings from Patient III-1 showing mildly diminished oscillatory potentials at age 7 progressing to marked attenuation by age 15.

FIG. 5.

Multifocal ERG from Patient III-2 at age 13 (top) showing severe cone depression in the macula. Normal field is shown below for comparison.

FIG. 6.

Fluorescein angiogram from Patient III-2 at age 14. The angiogram shows leakage from the optic nerve, but no vasculitis or cystoid macular edema. The times indicated are in minutes and seconds from injection of fluorescein. Images A, B, D, and F are from the right eye; images C and E are from the left eye.

DISCUSSION

The spleen is a hematopoietic organ capable of supporting the myeloid, erythroid, lymphoid, megakaryocytic, and reticuloendothelial systems [Wilkins, 2002]. The spleen also plays an important role in both cellular and humoral immunity through its lymphoid elements. Average weight of the spleen in both males and females is about 150 g [Gielchinsky et al., 1999]. In 1969, Dacie et al. [1969] described 10 patients with non-tropical idiopathic splenomegaly or “primary hypersplenism” that occurred in isolation without any evidence of lymphadenopathy, B symptoms of lymphoma, underlying liver disease, or immune thrombocytopenia. A follow-up study of these patients in 1978 found that 4 of the 10 patients developed malignant lymphomas, 8 months to 6 years after splenectomy, despite only mild cytological abnormalities in the pathologic specimens [Dacie et al., 1978].

McKinley et al. [1987] described an autosomal dominant disorder in three members of a family with splenomegaly from infancy, reduced circulating T-helper cells associated with germinal center hypoplasia in the spleen and lymph nodes. Bone marrow nodular hyperplasia was also a feature in one subject studied. All three affected members of the disorder had a benign course, with no recurrent infections. Familial splenomegaly is a rare occurrence and can be seen in adult life due to Gaucher disease, an autosomal recessive lysosomal storage disorder. Other storage disorders associated with splenomegaly that are autosomal recessive include Niemann–Pick disease and the mucopolysaccharidoses and other rare storage disorders. Fabry disease is an X-linked lysosomal storage disorder occasionally associated with angiokeratomas that were not present in any of our patients. Additionally, Fabry disease is X-linked and the preponderance of affected females in this family do not support an X-linked mode of inheritance. In our pedigree, there was no evidence of a storage disorder in any of the affected family members. It should be noted that the likely mode of inheritance of the phenotype described in this pedigree is autosomal dominant. Inherited hematologic disorders associated with splenomegaly include hereditary spherocytosis, thalassemia, and sickle cell disorders. Our pedigree had no clinical features of these disorders.

In addition to the present family’s constellation of hematological findings, their ophthalmic findings are unusual and characterized by the following: Early chronic optic nerve edema followed by slowly progressive visual loss, particularly central, and color vision. In all cases, despite continued optic nerve head edema, lumbar puncture did not show elevated pressure.

Although uveitis was found in the mother and one daughter, uveitis was mild and not present at all exams or ever seen in the first case study. Uveitis was considered as a possible diagnosis; however, vision loss in uveitis is usually associated with cystoid macular edema (CME) or vasculitis. A fluorescein angiogram performed on Patient III-2 did not show evidence of vasculitis or CME (Fig. 6), and, in the mother, treatment with steroids and immunosuppression did not improve vision or prevent further vision loss. Furthermore, testing for common causes of uveitis were all negative. The fluorescein leakage seen at the optic nerve in Patient III-2 (Fig. 6) can be associated with inflammatory cells in the vitreous in the absence of uveitis. Some forms of retinitis pigmentosa also exhibit lymphocytes and other inflammatory cells in the vitreous [Newsome and Michels, 1988]. Taken together, these cases appear to be more suggestive of a Mendelian genetic disorder than a uveitic entity.

Retinitis pigmentosa is a heterogeneous syndrome which despite 184 known loci, only about 50% of retinitis pigmentosa cases have a known genetic cause. [Wright et al., 2010]. Inheritance patterns of retinitis pigmentosa may be autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, x-linked, or digenic. These three patients from nonconsanguineous unions lacked neurological disorders such as ataxia and deafness that can be associated with retinitis pigmentosa.

All three affected family members showed disease progression similar to that observed in a cone or cone-rod dystrophy and was less suggestive of retinitis pigmentosa, a rod-cone dystrophy. Note only early cone dysfunction in Figure 4 and significant macular dysfunction in the multifocal ERGs in Figure 5.

ERGs conducted on the patients shed some light into the etiology of the vision loss. We first recorded full-field ERGs in all three subjects beginning at ages 7, 11, and 17 years. There was variability in expression in their visual loss. Two of the three maintained normal scotopic (rod) ERGs into their teenage years. The ERGs of Patient III-1 with the most severe expression depicted slowing of photopic (cone) b-wave implicit times (36 msec), and her oscillatory potentials were diminished by age 7 progressing to no recordable ERGs by age 15 (Fig. 4). The patient with least severe expression maintained normal full-field scotopic and photopic ERGs until past age 13. However, dramatic loss of her central retinal cone function was observed using multifocal ERGs at age 13 (Fig. 5).

Two patients maintained normal range full-field scotopic ERGs through their late teenage years (III-1, III-2) with their cone physiology diminishing rapidly. By ages 15 to early 20s, all three patients had completely extinguished full-field ERGs.

The full-field ERGs followed the course similar to cone dystrophy into adolescence for most severe expression and into mid-teenage years for the other two patients. In a short time period of a few years, the full-field ERGs including rod function attenuated to no recordable ERG responses. We are not aware of any cone dystrophies that share the constellation of symptoms found in this cohort.

No examples of a similar constellation of findings could be found in the ophthalmic literature. For example, our patients lack failure to thrive, intestinal absorption deficiencies, developmental delay, and other signs of Bassen–Kornzweig syndrome which can present with progressive vision loss, and this family also does not exhibit deafness or diabetes mellitus as is found in thiamine-responsive megaloblastic anemia, a disorder reported to have progressive cone-rod dystrophy and optic atrophy.

The anhidrosis and associated urticaria are curious. There is no evidence in any of the patients of a generalized autonomic disorder. There are cases of anhydrosis and cholinergic-induced urticaria reported [Itakura et al., 2000], however, these cases are not associated with splenomegaly or visual loss.

The patients in this family also experienced migraine headaches. Since migraine headaches are common in the population in general, we are uncertain whether they are truly associated with these patients’ inherited disorder.

In the family of three patients we described, common clinical and laboratory features include splenomegaly, vision loss, cytopenias, and anhidrosis. Cytopenias were due to splenic sequestration and not to a bone marrow process since bone marrow evaluations were normal, and splenectomy normalized complete blood count values. Splenic pathology revealed congestion without infiltration or extramedullary hematopoiesis. No occult primary lymphoma was identified in two subjects who had splenectomy even after a period of more than 10 years.

Though it is not known if the grandparents (I-1 and I-2) of the proband (III-2) have a similar phenotype, the fact that the proposita’s mother (II-3) has two affected offspring (III-1 and III-2), with different fathers (II-2 and II-4, respectively), from nonconsanguineous unions strongly supports an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. All three patients had vision loss noted before the age of 10 years; there is no strong evidence for anticipation in their pedigree. Since the phenotype of the grandparents (I-1 and I-2) of the proposita (III-2) is unknown and they are unavailable for genetic testing, pinpointing the causal alleles and their subsequent segregation with disease in our affected patients from whom we have robust phenotyping and DNA will enable determination of penetrance. The possibility remains that this is a de novo disease and presents for the first time in Patient II-3 (the parents may or may not have had the disease, or had a milder form of the disease). Since well-characterized phenotypic information and DNA are available for two generations in this one family (II and III) on both affected and unaffected family members, whole exome sequencing is underway to pinpoint disease causality. Whole exome sequencing will enable us to ascertain single nucleotide base pair mutations and gene deletion/duplication (e.g., copy number variation) simultaneously [Sathirapongsasuti et al., 2011; Norton et al., 2011]. Physicians should be aware of this unusual clinical syndrome.

Acknowledgments

Grant sponsor: Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc., New York, NY.

This work was supported by ARUP Institute for Clinical and Experimental Pathology. LBW, DJC, MMD, ATV, and KBD are supported in part by an unrestricted grant to the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Moran Eye Center, University of Utah Health Sciences Center, from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc., New York, NY.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

SKT, LBW, and GMR analyzed and interpreted data and wrote the paper. DJC, KJS, MMD, ATV, and KBD analyzed and interpreted data and contributed to writing of the paper. FCC performed the electron microscopic studies and contributed to writing of the paper.

References

- Dacie JV, Brain MC, Harrison CV, Lewis SM, Worlledge SM. Non-tropical idiopathic splenomegaly (primary hypersplenism): A review of 10 cases and their relationship to malignant lymphomas. Br J Haematol. 1969;17:317–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1969.tb01378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dacie JV, Galton DA, Gordon-Smith EC, Harrison CV. Non-tropical idiopathic splenomegaly: A follow-up study of 10 patients described in 1969. Br J Haematol. 1978;38:185–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1978.tb01035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gielchinsky Y, Elstein D, Hadas-Halpern I, Lahad A, Abrahamov A, Zimran A. Is there a correlation between degree of splenomegaly, symptoms and hypersplenism? A study of 218 patients with Gaucher disease. Br J Haematol. 1999;106:812–816. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itakura E, Urabe K, Yasumoto S, Nakayama J, Furue M. Cholinergic urticaria associated with acquired generalized hypohydrosis: Report of a case and review of the literature. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:1064–1066. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley RA, Kwan YL, Lam-Po-Tang PR. Familial splenomegaly syndrome with reduced circulating T helper cells and splenic germinal centre hypoplasia. Br J Haematol. 1987;67:393–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1987.tb06159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newsome DA, Michels RG. Detection of lymphocytes in the vitreous gel of patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988;105:596–602. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(88)90050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton N, Li D, Rieder MJ, Siegfried JD, Rampersaud E, Zuchner S, Mangos S, Gonzalez-Quintana J, Wang L, McGee S, Reiser J, Martin E, Nickerson DA, Hershberger RE. Genome-wide studies of copy number variation and exome sequencing identify rare variants in BAG3 as a cause of dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sathirapongsasuti JF, Lee H, Horst BA, Brunner G, Cochran AJ, Binder S, Quackenbush J, Nelson SF. Exome sequencing- based copy-number variation and loss of heterozygosity detection: Exome CNV. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2648–2654. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins BS. The spleen. Br J Haematol. 2002;117:265–274. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright AF, Chakarova CF, Abd El-Aziz MM, Bhattacharya SS. Photoreceptor degeneration: Genetic and mechanistic dissection of a complex trait. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:273–284. doi: 10.1038/nrg2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]