Abstract

Approximately 400,000 ventral hernia repair surgeries are performed each year in the United States. Many of these procedures are performed using laparoscopic minimally invasive techniques and employ the use of surgical mesh. The use of surgical mesh has been shown to reduce recurrence rates compared to standard suture repairs. The placement of surgical mesh in a ventral hernia repair procedure can be challenging, and may even complicate the procedure. Others have attempted to provide commercial solutions to the problems of mesh placement, but these have not been well accepted by the clinical community. In this article, two versions of shape memory polymer (SMP)-modified surgical mesh, and unmodified surgical mesh, were compared by performing laparoscopic manipulation in an acute porcine model. Also, SMP-integrated polyester surgical meshes were implanted in four rats for 30–33 days to evaluate chronic biocompatibility and capacity for tissue integration. Porcine results show that the modified mesh provides a controlled, temperature-activated, automated deployment when compared to an unmodified mesh. In rats, results indicate that implanted SMP-modified meshes exhibit exceptional biocompatibility and excellent integration with surrounding tissue with no noticeable differences from the unmodified counterpart. This article provides further evidence that an SMP-modified surgical mesh promises reduction in surgical placement time and that such a mesh is not substantially different from unmodified meshes in chronic biocompatibility.

Keywords: shape memory polymer, hernia repair, mesh placement, surgical mesh, laparoscopic surgery

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 400,000–500,000 laparoscopic ventral/incisional hernia repair procedures are performed each year in the United States.1 Minimally invasive laparoscopic surgery has become an increasingly popular method to repair such ventral hernias.2,3 Evaluating post-laparoscopic surgery outcomes has confirmed that the use of tissue-reinforcing mesh can significantly reduce morbidity and lower recurrence rates.1,4 In a article by Burger et al.,1 patients presenting with small incisional hernias had a recurrence rate of 67% with a suture repair; however, these rates dropped to 17% with a mesh repair. Although the use of laparoscopic techniques with surgical mesh has been shown to reduce recurrence rates, the placement and positioning of surgical mesh can prove challenging for surgeons, potentially increasing operating time and patient complications.5,6 Ventral hernia repair surgeries often involve a complicated ballet of folding and rolling surgical mesh to fit through an abdominal port. Once in the abdominal cavity, the mesh must be meticulously unfolded, formed to fit the anatomy and attached with tacks, sutures, or other methods. The unfolding and placement of ventral hernia repair mesh can require a significant amount of time, which may increase the occurrence of surgical complications such as recurrence, infection, or pain. Biomedical engineers have attempted to make mesh placement easier, using specialized techniques or materials to push mesh into a specific shape, but unfortunately to date these have not proven widely successful.7 One example of a product attempting to improve mesh placement is the Davol Bard® Composix® Kugel® patch.8,9 The Kugel patch was voluntarily recalled by the manufacturer due to potentially dangerous complications.8 Other companies have introduced complicated mechanical apparatuses to aid in mesh unfolding, which add expense, cumbersomeness, and bulk to the device.

This research examines a new approach by utilizing a shape memory polymer (SMP) coating to facilitate automated, controlled unrolling as the mesh reaches body temperature. SMPs are a specific classification of polymers that are able to automatically recover large strains when activated by a trigger, like temperature, for example.10 For this study, we chose to use polyester surgical meshes as the baseline mesh to be modified since these meshes are highly flexible and offer a variety of pore size options. Polyester has also shown excellent biocompatibility in hernia repair applications.11 It has also been suggested that polyester possesses stronger tissue ingrowth characteristics, with less inherent contraction and no significant difference in fibroblastic reaction versus polypropylene, another commonly used material.12 Note, however, that the SMP modification used here for polyster can also be used with other mesh materials. The SMP used has highly tailorable features including thermally triggered deployment, precise control of deployment time, and precise control of mechanical stiffness. An earlier in vitro and preliminary in vivo study showed that SMP-coated meshes provide excellent control of self-deployment [11]; however, this study did not evaluate in vivo deployment of multiple SMP-mesh configurations or study longer term biocompatibility and tissue integration, all key issues that need to be addressed prior to any human use.

MATERIALS AND EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

Creating the modified surgical mesh samples was accomplished by integrating the novel SMP into a commercially available polyester mesh (PETKM7001, Textile Development Associates). Modified and unmodified surgical meshes were evaluated using dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA), a chronic animal study in rats, and an acute porcine study.

Synthesis

Chemicals tert-Butyl acrylate (tBA) and 2,2-dimethoxy-2-phenylacetophenone (DMPA) photo-initiator were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, and poly(ethylene glycol) dimethacrylate (PEGDMA) with average molecular weight of Mn = 1000 was obtained from PolySciences. A polymer solution was prepared by combining 78 wt% tBA, 22 wt% PEGDMA, and 0.25–0.3 wt% DMPA.

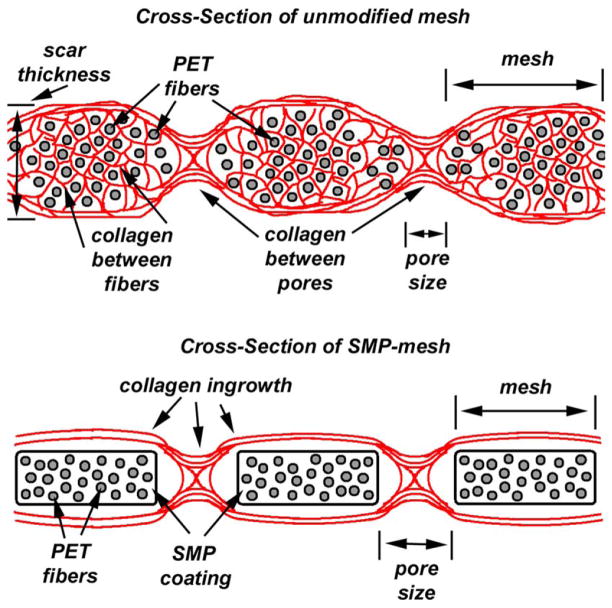

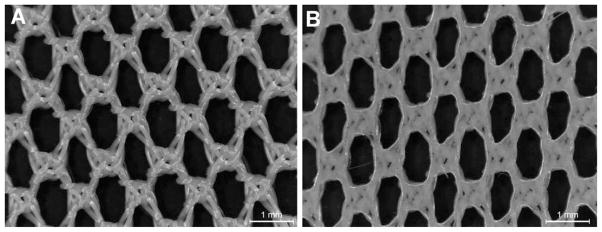

Polymer solution was applied to commercially available surgical meshes using ultra-violet (UV)-polymerization. Similar SMP combinations and SMP surgical meshes have been previously described by our group.10,13 Surgical meshes were placed in glass molds (100 × 100 mm) in a flat configuration and SMP solution was injected and subsequently cured using a Dymax 2000-PC 365 nm ultraviolet lamp. Non-porous SMP-modified meshes were created by filling the mold with SMP, resulting in a mesh embedded in SMP. Porous SMP-modified meshes were created by first purging the mold with nitrogen gas, injecting SMP solution to coat the mesh fibers, and the excess SMP is drained from the mold. The mold was continually purged with nitrogen gas during the polymerization process to prevent oxygen inhibition. UV intensity was approximately 15–25 mW/cm2 at the mold surface; and the source was pulsed on and off every 30 s for a total exposure time of 20 min. Excellent retention of the original pore size of the unmodified mesh was obtained using this process. The approximate thickness of each sample was 0.35 mm for unmodified polyester mesh; 0.70 mm for SMP-coated porous polyester mesh, and 1.0 mm for non-porous SMP mesh. A photomicrograph comparing an unmodified mesh with a porous SMP-mesh is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

(a) Unmodified mesh; (b) SMP-coated porous polyester surgical mesh.

Dynamic mechanical analysis

DMA was performed using a TA Q800 DMA to verify glass transition temperature (Tg) and storage modulus of the SMP formulation. Settings included cyclic strain control at 0.1% strain and at a frequency of 1.0 Hz. A detailed description of the DMA procedure can be found in previous work by Zimkowski et al.13 The DMA study was performed on the SMP formulation alone and the surgical mesh integrated with SMP in both the lengthwise and widthwise directions to evaluate any potential change in Tg resulting from the SMP-mesh composite formulation. All samples were cut to approximately 25 mm long × 5.5 mm wide × 1 mm thick.

Cytotoxicity study

Cytotoxicity testing was performed by WuXi AppTec (St. Paul, MN) using a MEM elution method compliant with ISO 10993-5:2009. Non-porous SMP-mesh was sterilized by autoclave and used in this test to maximize sample exposure. The test consists of an extraction process, an exposure process and experimental evaluation. The test article was prepared using an extraction ratio of 60 cm2 of SMP-mesh sample per 20 mL, and 30 cm2 was extracted in 10 mL of Eagle’s MEM +5% fetal bovine serum. The sample was extracted at 37°C for 24 h. The media are then inoculated into a L-929 mouse fibroblast cell line and the cells are incubated at 37°C. Cultures were evaluated for cytotoxic effects by microscopic observation at 24-, 48-, and 72-h incubation periods.

Criteria for evaluating cytotoxicity included morphologic changes in cells, such as granulation, crenation, or rounding, and loss of viable cells from the monolayer by lysis or detachment. Evaluation scoring was performed according to the ISO standards, wherein test results of ‘0,’ ‘1,’ or ‘2’ are considered non-toxic and results of ‘3’ or ‘4’ are considered toxic. A score of ‘0’ suggestions there was no reactivity, no cell lysis, and no reduction of cell growth. A score of ‘4’ suggests severe reactivity and nearly complete destruction of the cell layers.

Acute large animal study

This study was conducted under a test protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC protocol 87912(04)1D), and the experiment was performed in a single live female pig weighing approximately 55 kg. The swine was anesthetized using ketamine and xylazine for induction and isoflurane for maintenance, and secured in a supine position. Several laparoscopic ports were inserted to perform experiments within the abdominal cavity. At the completion of testing, the animal was euthanized with Sleepaway (sodium pentobarbital).

This study was performed to evaluate laparoscopic manipulation and placement of a fully SMP coated mesh, a porous SMP-coated mesh, and an unmodified polyester mesh, based on a procedure outlined by Zimkowski et al.13 The surgical procedure consisted of placing three hernia meshes approximately 80 × 80 mm in size (fully SMP-coated, porous SMP-coated, and unmodified) against the porcine abdominal wall using standard intraperitoneal laparoscopic approach. No peritoneal defect was created in this study. Modified surgical meshes were submerged in water heated to approximately 60°C, rolled to fit into a cannula port and cooled by submerging in water cooled to approximately 20°C. Each SMP-modified mesh retained a rolled shape once cooled, and was inserted into the abdominal cavity of the swine using a 12 mm laparoscopic cannula port. The surgeon positioned each mesh in the abdominal cavity and began manipulation for placement. All surgical meshes were secured to the abdominal wall using 5 mm tacks (Protack, Covidien).

Chronic small animal study

This study was conducted under a test protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC protocol 43812(08)1D), and the experiment was performed using four female Sprague Dawley rats weighing approximately 310–370 g obtained from Charles River Laboratories. Experimental procedure was based upon a procedure outlined by Horan et al.14 Each rat was anesthetized before surgery using ketamine and xylazine, or inhaled isoflurane. For pain relief, carprofen was administered subcutaneously the day of surgery, and for 2 days post-op.

Once anesthetized, each rat was placed in a supine position, and using surgical dissection techniques, an opening of skin was created to expose the abdominal muscle wall underneath. Two small punctures (0.5 × 1 cm or smaller) were created in the muscle wall using a scalpel. The punctures were positioned on each side of the animal abdominal wall, inferior to the rib cage, and superior to the pelvis. Surgical meshes implanted measured approximately 1 × 2 cm. The left side of the animal received the experimental SMP-integrated porous mesh, and the right side of the animal received the unmodified control mesh. Each surgical mesh was centered over a defect subcutaneously and secured to the muscle wall using non-absorbable sutures. The opening of skin previously exposed was closed with sutures and surgical clips, covering the abdominal wall and surgical mesh. An example of the puncture created is shown in Figure 2(a), and implantation of the surgical mesh is shown in Figure 2(b).

FIGURE 2.

(a) Abdominal wall defect is created; (b) repaired with implanted surgical mesh and the wound is closed with clips. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

After 30–33 days, each animal was euthanized by carbon dioxide asphyxiation, and all abdominal wall tissue surrounding the hernia mesh was harvested. Histology studies were performed on excised tissue to investigate evidence of inflammation and mesh ingrowth. Dissected tissue samples were fixed using phosphate-buffered saline formalin solution. Transverse tissue cross-sections, including epidermis through muscle wall, were sectioned and embedded in paraffin for histological evaluation. A microtome was used to create slides. Slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for evaluation. Slides were assessed by a qualified pathologist.

EXPERIMENTAL RESULTS

Dynamic mechanical analysis

DMA samples were characterized by storage modulus and the tan delta curve. The glass transition temperature (Tg) was determined to be the peak of the tan delta curve. The similarities of Tg across the DMA samples indicate mesh has minimal effect on native SMP Tg characteristics. Results are shown in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

SMP/SMP-Mesh characteristics: (a) SMP alone shows Tg = 41.5 ± 0.7°C; (b) SMP + Mesh tested in lengthwise direction shows Tg = 41.0 ± 1.0°C; (c) SMP + Mesh tested in widthwise direction shows Tg = 36.4 ± 2.6°C.

Cytotoxicity study

The SMP-modified mesh presented a non-toxic response, with no reduction of cell growth or cell lysis observed. The SMP-modified mesh was deemed non-cytotoxic under the test conditions employed. Results are presented in Table I.

TABLE I.

Cytotoxicity Results

| Polymer Network | Score (24/48/72 h) |

|---|---|

| 78/22 SMP-Mesh | 0/0/0 |

Acute large animal study

The acute animal study was performed to evaluate unrolling and placement of modified and unmodified surgical mesh in an in vivo environment. Three surgical meshes were evaluated: an unmodified polyester mesh, a non-porous SMP-modified polyester mesh, and a porous SMP-modified polyester mesh. Each surgical mesh was inserted through a 12 mm laparoscopic port, positioned and tacked in place. Mesh unrolling time was monitored over the duration of the procedure. In the rolled configuration, each mesh was easily inserted through the cannula port and manipulated using common laparoscopic tools. Upon insertion into the abdominal cavity, both SMP-modified meshes unrolled automatically and required little manipulation. However, the unmodified mesh required 65 s to unroll, with more manual manipulation and positioning necessary. The fully coated SMP mesh unrolled in approximately 25 s. The porous SMP mesh unrolled in approximately 31 s, requiring very little manipulation, representing more than a 50% decrease in placement time compared to unmodified mesh. In vivo unrolling of the non-porous SMP-modified mesh is shown in Figure 4, and unrolling of the porous SMP-modified mesh is shown in Figure 5.

FIGURE 4.

Non-porous fully coated SMP-mesh automatically unrolls after 25 s as the sample reaches body temperature. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

FIGURE 5.

Porous SMP-Mesh automatically unrolls after 31 s as the sample reaches body temperature. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Chronic small animal study

Tissue ingrowth in hernia meshes is extremely important for repair strength; the chronic small animal study allowed evaluation of in vivo tissue ingrowth of the porous SMP-modified surgical mesh. All four animals survived to the end of the study, with no outward signs of infection or complications. An anterior view of a shaved rat abdomen after 30 days post-op is shown in Figure 6. The SMP-modified mesh sutures are identified by blue arrows and the control mesh sutures are identified by red arrows. Contraction of each mesh was qualitatively observed; however, the SMP-modified mesh showed markedly less contraction than the unmodified control mesh. Mesh contraction is a normal process in wound healing, but significant contraction may contribute to hernia reoccurrence.

FIGURE 6.

Abdominal view of a shaved rat 30 days post-op; red arrows (left) indicate unmodified (control) mesh suture locations and blue arrows (right) indicate SMP-mesh suture locations. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

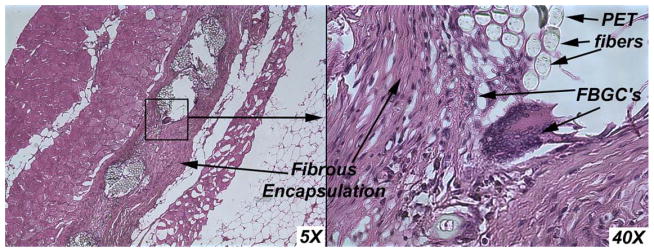

Hematoxylin and eosin-stained micrographs of the tissue reaction towards the unmodified mesh are shown in Figure 7. Tissue reaction toward the SMP-modified mesh is shown in Figure 8. Polyester mesh fibers are identified by “PET,” shape memory polymer is identified by “SMP,” and foreign body giant cells are identified by “FBGC.”

FIGURE 7.

Unmodified control mesh tissue ingrowth. Inflammatory response is as expected, demonstrating tissue ingrowth into polyester fibers and mesh pores. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

FIGURE 8.

SMP-modified mesh demonstrates similar tissue ingrowth characteristics. Inflammatory response is similar, demonstrating expected tissue ingrowth into mesh pores. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

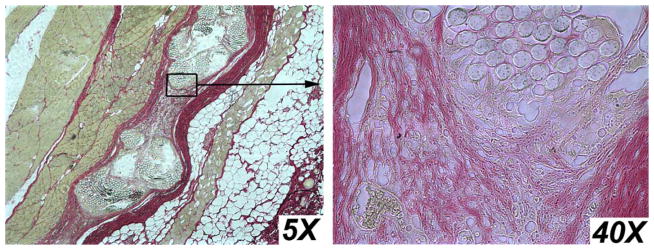

Picrosirius red staining was used to visualize collagen ingrowth into mesh. Picrosirius red stained micrographs of unmodified mesh samples are shown in Figure 9. Micrographs of SMP-modified mesh are shown in Figure 10.

FIGURE 9.

Picrosirius Red stain shows collagen ingrowth into unmodified mesh. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

FIGURE 10.

Picrosirius Red stain show collage ingrowth into SMP-modified mesh. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

DISCUSSION

The placement of surgical mesh can be difficult in ventral hernia repair procedures. The surgeon must roll or compact the mesh, force it through a cannula port into the laparoscopic cavity, unfold the mesh, position it vertically to the repair site, form the mesh to the anatomy and suture or tack it in place. This process can require significant time during surgery, which can potentially increase the risk of complications. To overcome the mesh placement difficulties, we propose integrating a SMP into polyester surgical meshes to provide automated unrolling in ventral hernia repair applications. Little biocompatibility data of SMPs has been published in the literature; so, in continuation with our previous studies,13 we evaluated a fully coated SMP-modified mesh, a porous SMP-modified medium-weight polyester surgical meshes and unmodified polyester meshes in in vivo studies.

When developing an SMP-modified surgical mesh, two important considerations are activation temperature and tissue ingrowth. Activation temperature (Tg) of SMP used in this study was found to be 41°C, and as shown in Figure 3, the polyester surgical mesh has very little impact on the thermomechanical characteristics of the pure SMP. The tested surgical mesh, fully encapsulated in SMP, similar to a mesh previously described by our group is shown in Figure 4.13 This mesh was non-porous and thicker than typical surgical meshes used in ventral hernia repair applications and not feasible for long-term implantation. However, this mesh serves as a proof-of-concept and experimental control to compare with the porous SMP-modified mesh and unmodified mesh. The non-porous SMP-mesh took approximately 25 s to unroll; the porous SMP-mesh took approximately 31 s to unroll. While the non-porous SMP-mesh unrolled 9% faster than the porous SMP-mesh, the slight difference did not have a noteworthy impact on mesh unrolling in vivo. This indicates that the porous coating can be applied in a minimalistic way, while achieving the desired unrolling effect and allowing for tissue ingrowth.

In hernia repair applications, pore size of mesh is an important consideration for the wound healing process. Fibroblasts, macrophages, and other cells must infiltrate the mesh pores to allow tissue reinforcing integration and prevent infection. To our knowledge, no other research has been performed regarding biocompatibility of SMP-integrated composite surgical meshes. When creating a composite material which combines a new SMP with an existing mesh, the biocompatibility and tissue ingrowth characteristics are important considerations. As shown in Figures 7 and 8, both experimental and control meshes displayed similar characteristic fibrous encapsulation and presence of foreign body giant cells, as expected with implantation. No notable differences with chronic inflammatory response or tissue ingrowth were observed between the control and experimental mesh implants.

The mechanism of tissue ingrowth into hernia meshes is thought to consist primarily of collagen Type I and Type III, with the ratio between them having an effect on reoccurrence.15 How the mechanisms of collage ingrowth relate to the unmodified and SMP-modified mesh is shown in Figure 11.

FIGURE 11.

Tissue ingrowth of: unmodified mesh (top), with collagen fibers extending between PET fibers and through mesh pores. SMP-modified mesh (bottom), with collagen fibers extending through mesh pores only, SMP coating prevents thick scar formation. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Tissue ingrowth is thought to occur in typical unmodified meshes by the creation of a scar (collagen type I and III) encapsulating the mesh. Inflammatory cells and fibro-blasts migrate through mesh pores and between individual woven mesh strands, laying down collagen to bind the mesh to surrounding tissue. In the SMP-modified mesh, the SMP coating prevents ingrowth between individual mesh strands, but allows growth through pores. By reducing the amount of cellular migration through individual mesh fibers, scar formation appears thinner and less noticeable by touch. A thicker scar formation suggests that a patient may have more perceived foreign body sensation and increased mesh contraction. Figures 9 and 10 depict these mechanisms, where red staining identifies collagen. In Figure 9, it can be observed that individual woven mesh stands are separated, and collagen fibers have been laid down as fibroblasts migrate through the mesh. Conversely, in Figure 10, it can be observed that collagen ingrowth has only occurred between the pores, but not through individual mesh strands. The SMP-modified mesh appears to create a thinner scar than the unmodified mesh.

Mesh contraction was observed in both control and experimental groups; however, the experimental group displayed markedly less contraction. This could potentially be attributed to the SMP coating encapsulating the fine mesh fibers. The macroscopic pores show similar tissue integration between the control and experimental groups, but in the control group, individual mesh fibers begin to separate from the large weave as cells infiltrate. In the experimental mesh, the SMP coats and penetrates the mesh fibers, binding them together, and preventing cellular infiltration into individual fiber strands. The SMP did not appear to hinder tissue ingrowth between macroscopic pores, however, and we hypothesize these factors may contribute to a less severe inflammatory response, and less perceptible scar formation, without sacrificing reinforcing strength. It has been demonstrated that tissue contraction and ingrowth characteristics change as implant size changes;12,16 therefore, larger animal studies using a more clinically relevant mesh size would be a logical next step in evaluating the SMP-modified mesh. These future studies will investigate conformity, compliance, adhesion formation, and ingrowth strength characteristics.

CONCLUSION

SMP-integrated surgical meshes may provide a reduction in surgical-operating time. SMPs are synthesized by controlling composition with two or more polymer components with specific cross-linking and glass transition temperature characteristics. We believe that integrating a SMP could improve existing surgical mesh characteristics to facilitate automatic mesh unrolling in vivo, without sacrificing the existing surgical mesh strength. Automated mesh unrolling could greatly improve laparoscopic hernia repair outcomes and reduce operating time. The SMP we have developed for this application has shown excellent preliminary in vivo biocompatibility in rats, and has shown excellent unrolling behavior in vivo compared to unmodified mesh, in an acute porcine model. One of the next steps in the development of this SMP technology is chronic large animal studies using clinically relevant mesh sizes to evaluate longer term mesh contraction and tissue ingrowth characteristics of SMP-modified meshes, compared to unmodified meshes.

References

- 1.Burger JWA, Luijendijk RW, Hop WCJ, Halm JA, Verdaasdonk EGG, Jeekel J. Long-term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of suture versus mesh repair of incisional hernia. Ann Surg. 2004;240:578–585. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000141193.08524.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Townsend CM, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery: The Biological Basis of Modern Surgical Practice. 18. New York, NY: Saunders Elsevier; 2007. pp. 1155–1179. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hunter JG. Clinical trials and the development of laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:1–3. doi: 10.1007/s004640000385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cortes R, Miranda E, Lee H, Gertner M. Biomaterials and the Evolution of Hernia Repair I: The History of Biomaterials and the Permanent Meshes. In: Norton J, Barie P, Bollinger RR, Chang A, Lowry S, Mulvihill S, Pass H, Thompson R, editors. Surgery. New York, NY: Springer; 2008. pp. 2291–2304. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tatum RP, Shalhub S, Oelschlager BK, Pellegrini CA. Complications of PTFE mesh at the diaphragmatic hiatus. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;12:953–957. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0316-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heniford BT, Park A, Ramshaw BJ, Voeller G. Laparoscopic Repair of Ventral Hernias: Nine Years’ Experience With 850 Consecutive Hernias. Trans Meet Am Surg Assoc. 2003;121:85–94. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000086662.49499.ab. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hope WW, Iannitti DA. An algorithm for managing patients who have Composix® Kugel® ventral hernia mesh. Hernia. 2009;13:475–479. doi: 10.1007/s10029-009-0498-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA): Center for Devices and Radiological Health. [accessed in December 5, 2011];Class 1 Recall: Bard® Composix® Kugel® Mesh Patch - Expansion. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/RecallsCorrectionsRemovals/ListofRecalls/ucm062944.htm.

- 9.Berrevoet F, Sommeling C, Gendt S, Breusegem C, Hemptinne B. The preperitoneal memory-ring patch for inguinal hernia: a prospective multicentric feasibility study. Hernia. 2009;13:243–249. doi: 10.1007/s10029-009-0475-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yakacki CM, Shandas R, Safranski D, Ortega AM, Sassaman K, Gall K. Strong, tailored, biocompatible shape-memory polymer networks. Adv Funct Mater. 2008;18:2428–2435. doi: 10.1002/adfm.200701049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klosterhalfen B, Klinge U, Schumpelick V, Tietze L. Polymers in hernia repair - common polyester vs. polypropylene surgical meshes. J Mater Sci. 2000;35:4769–4776. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonzalez R, Fugate K, McClusky D, III, Ritter EM, Lederman A, Dillehay D, Smith CD, Ramshaw BJ. Relationship Between Tissue Ingrowth and Mesh Contraction. World J Surg. 2005;29:1038–1043. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-7786-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zimkowski MM, Rentschler ME, Schoen J, Rech BA, Mandava N, Shandas R. Integrating a novel shape memory polymer into surgical meshes decreases placement time in laparoscopic surgery: An in vitro and acute in vivo study. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2013:2613–2620. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horan R, Bramono D, Stanley J, Simmons Q, Chen J, Boepple H, Altman GH. Biological and biomechanical assessment of a long-term bioresorbable silk-derived surgical mesh in an abdominal body wall defect model. HERNIA. 2009;13:189–199. doi: 10.1007/s10029-008-0459-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baktir A, Dogru O, Girgin M, Aygen E, Kanat BH, Dabak DO, Kuloglu T. The effects of different prosthetic materials on the formation of collagen types in incisional hernia. Hernia. 2013;17:249–253. doi: 10.1007/s10029-012-0979-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klinge U, Conze J, Klosterhalfen B, Limberg W, Obolenski B, Ottinger AP, Schumpelick V. Changes in abdominal wall mechanics after mesh implantation. Experimental changes in mesh stability. Langenbecks. 1996;381:323–332. doi: 10.1007/BF00191312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]