Abstract

Introduction Fusarium spp is an omnipresent fungal species that may lead to fatal infections in immunocompromised populations. Spontaneous intracranial infection by Fusarium spp in immunocompetent individuals is exceedingly rare.

Case Report An immunocompetent 33-year-old Hispanic woman presented with persistent headaches and was found to have a contrast-enhancing mass in the left petrous apex and prepontine cistern. She underwent a subsequent craniotomy for biopsy and partial resection that revealed a Fusarium abscess. She had a left transient partial oculomotor palsy following the operation that resolved over the next few weeks. She was treated with long-term intravenous antifungal therapy and remained at her neurologic baseline 18 months following the intervention.

Discussion To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of Fusarium spp brain abscess in an immunocompetent patient. Treatment options include surgical intervention and various antifungal medications.

Conclusion This case demonstrates the rare potential of intracranial Fusarium infection in the immunocompetent host, as well as its successful treatment with surgical aspiration and antifungal therapy.

Keywords: intracranial abscess, Fusarium, fungal infection

Introduction

Fusarium spp is a common fungal mold with many subsets found in soil, plants, and air.1 2 The fungal species is an important plant pathogen and has become increasingly recognized as a human pathogen on account of its potential for systemic toxicity and death in immunocompromised patients.2 Fusarium spp infections can be localized, focally invasive, or disseminated.3 Although localized and focally invasive infections are not uncommon in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients, dissemination of disease is quite rare in the former population. Localized single-organ infections generally present as keratitis, onychomycosis, endophthalmitis, or cutaneous infections. Focally invasive fungal infection is often associated with foreign bodies from trauma or hospital catheters. Disseminated disease usually arises in patients with hematologic malignancies and affects the skin, lungs, and/or sinuses in most cases.4

We report a rare case of an intracranial Fusarium spp abscess localized in the left petrous apex and prepontine cistern in an immunocompetent and otherwise healthy patient who lacked any known risk factors for fungal infection.

Case Report

A 33-year-old right-handed Hispanic woman presented with a 1-year history of intermittent left-sided facial pain and headaches. She described the pain as sharp and severe in the left eye, head, and face. In addition, she complained of intermittent hyperacusis of the left ear, photophobia of the left eye, and some numbness of the left face with the pain. Symptoms were centered mostly around the orbital and maxillary regions of the face, and spared the mandibular region. Her neurologist presumed that she had trigeminal neuralgia and prescribed pregabalin. Over time, she was also prescribed gabapentin, topiramate, and hydrocodone. There were no traumatic events in her history, and her only significant travel history was the occasional trip back to Mexico to visit family.

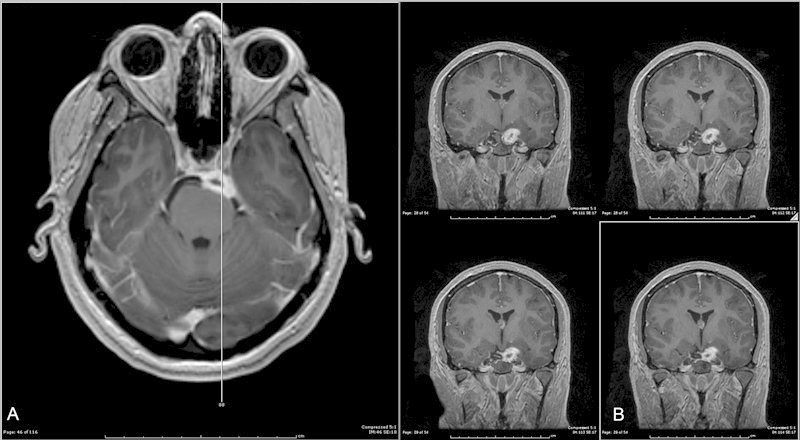

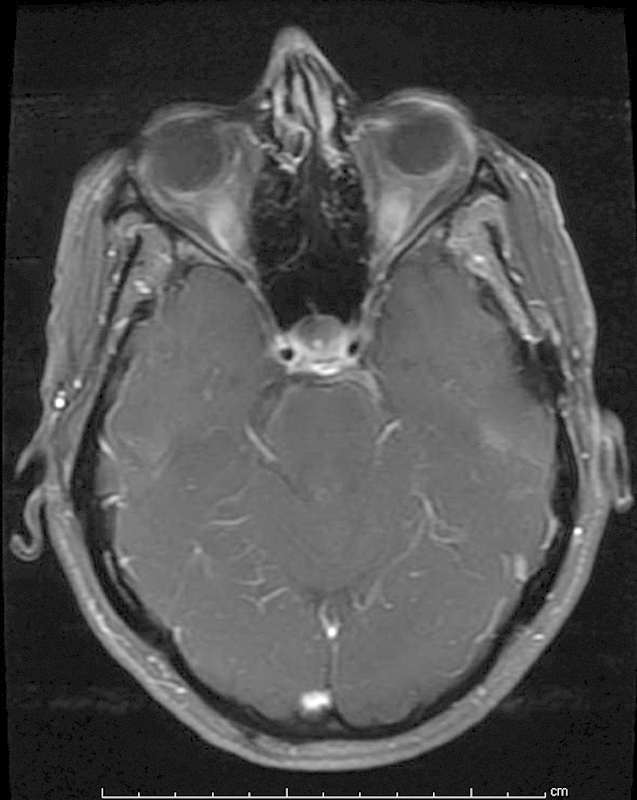

She presented to our hospital due to the persistence of these severe and refractory symptoms despite medical therapy. Other than hypertension, she had no other significant past medical history. Her neurologic examination on presentation was nonfocal with the exception of hyperacusis to finger rub in the left ear and hyperalgesia in the left V1 and V2 distributions. She was afebrile with a mildly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 21 mm/hour and a normal C-reactive protein level of 0.5 mg/L. A mild leukocytosis of 14.9 × 109/L was attributed to neutrophilic demargination from recent dexamethasone therapy. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain demonstrated an extra-axial contrast-enhancing mass at the left petrous apex and prepontine cistern (Fig. 1). Surrounding T2-hyperintense signal was seen in the region of the adjacent thalamus and hypothalamus, indicative of a potentially invasive process.

Fig. 1.

(A) Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain axial T1-weighted contrast-enhancing image demonstrating a left petrous apex and prepontine cistern lesion. (B) Four MRI brain coronal T1-weighted contrast-enhancing images of the same lesion.

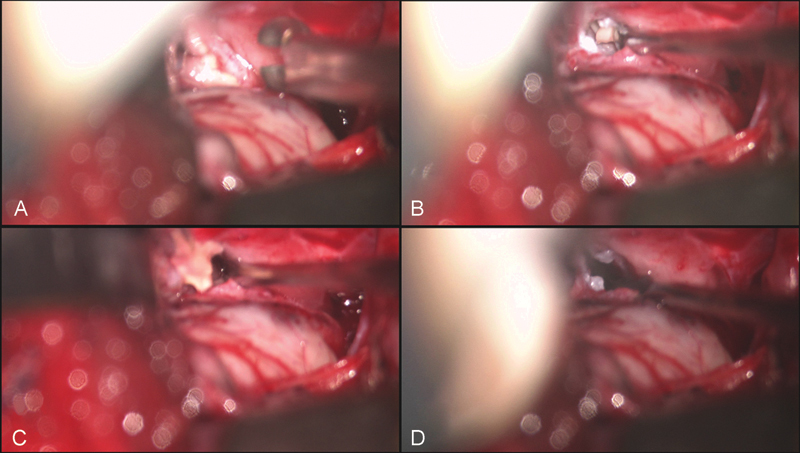

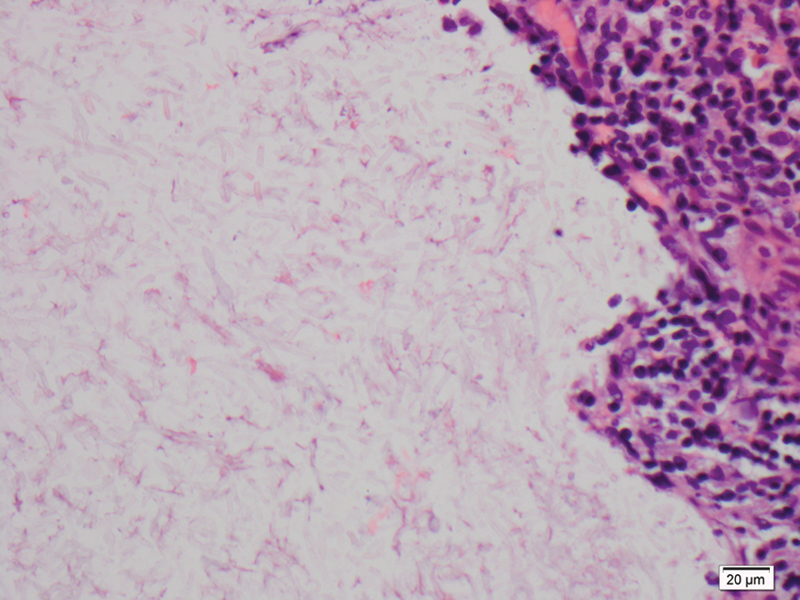

She underwent a left pterional craniotomy for biopsy and partial resection. Intraoperatively, yellowish necrotic purulence was noted upon incision into the lesion's capsule (Fig. 2). Pathologic examination with slides stained with hematoxylin and eosin noted hyphae (Fig. 3) and Gomori methenamine silver staining identified septated fungal organisms with acute angled branching (Fig. 4). Fusarium spp was confirmed with DNA polymerase chain reaction genetic analysis. Following the operation, she had a transient left oculomotor nerve palsy that resolved over the next few weeks.

Fig. 2.

Intraoperative still video capture of the abscess (A) prior to incision into the capsule, (B, C) during excision of the lesion, and (D) status postresection.

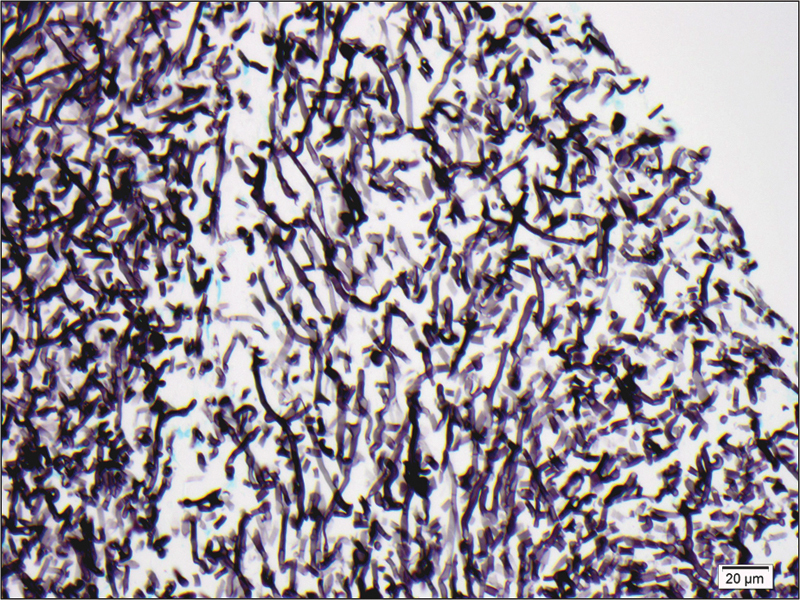

Fig. 3.

High-power hematoxylin and eosin stained slides of the surgical specimen demonstrating hyphae.

Fig. 4.

High-power Gomori methenamine silver stained slides confirming septated hyphae with acute angled branching.

The infectious disease service at our hospital recommended voriconazole, terbinafine, and amphotericin for the findings of this invasive intracranial Fusarium fungal abscess in the absence of a clear predisposing condition. Our patient remained neurologically stable postoperatively with the exception of an oculomotor nerve palsy, and she was discharged home 4 days later with long-term intravenous triple antifungal therapy and close clinical follow-up. Due to hematologic and constitutional side effects, the infectious disease service later deescalated the regimen to just voriconazole, which she tolerated well. At last neurosurgical follow-up 18 months postoperatively, her symptoms had improved and she complained only of occasional migraine-like headaches, with full resolution of her oculomotor paresis. A repeat MRI of the brain also demonstrated nearly complete resolution of the abscess (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Magnetic resonance imaging brain axial T1-weighted contrast-enhancing image demonstrating dramatic improvement in the Fusarium fungal abscess after both surgical evacuation and 7 months of antifungal therapy.

Discussion

Fusarium spp are hyaline filamentous fungi that have been reported to be the second leading cause of filamentous fungal infection morbidity in immunocompromised transplant patients, following only Aspergillus spp.5 As a pan-global fungus, Fusarium spp is becoming increasingly important due to the continued increase in the incidence of infection in the immunocompromised population. In immunocompetent patients, the fungus normally presents as benign skin, nail, or corneal infection and rarely invades or disseminates.6 There are reported to be a minimum of 69 Fusarium spp subsets that can cause human and/or animal fusariosis, of which F solani, F oxysporum, and F moniliforme are the most commonly related to human pathogenesis.4 7 The most commonly reported portals of entry for the fungus are through inhalation or skin trauma, with risk of dissemination associated with neutropenia and graft-versus-host disease.5

In our review of the literature, we found that Fusarium spp pathology may present across a wide spectrum. Keratitis,8 endophthalmitis,9 onychomycosis,10 11 cutaneous infections,12 13 peritonitis,14 fungemia,15 osteomyelitis,16 17 septic arthritis,18 19 20 otitis,21 sinusitis,22 23 pneumonia,24 vertebral abscess,16 brain abscess, and other central nervous system (CNS) infections25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 are all possible presentations of this fungus.4 Of general importance are those presentations that commonly serve as portals of entry such as keratitis, endophthalmitis, onychomycosis, and cutaneous infection because these methods of fungal infection can lead to potentially fatal dissemination; 50 to 80% mortality has been seen.4 6 Particular cases of brain abscess, vertebral abscess, and other CNS forms of infection are noteworthy to our case. Keratitis is one of the more common manifestations of Fusarium infection, especially following trauma or in tropical regions of the world. Although less frequent, keratitis is also associated with fungal infection of contact lenses due to improper care or inadequate cleansing by solution.8 Fungal keratitis can further develop into endophthalmitis following intraocular spread. Trauma and surgery also provide routes of entry for Fusarium spp to cause endophthalmitis.9

A review of the literature resulted in four prior confirmed cases of Fusarium brain abscesses27 28 31 34 and several additional cases with probable brain involvement25 26 29 30 32 33 along with one case of vertebral abscess.16 Of these cases, only the vertebral abscess patient was immunocompetent. That patient presented with a distant history of trauma after a bamboo splinter, and a paravertebral abscess were removed 9 years prior at the same location of her Fusarium epidural thoracolumbar fungal abscess. In all four confirmed cases of brain abscesses, the patients had some type of immunosuppressive condition including chronic infectious mononucleosis syndrome,34 recent lung transplantation,31 acute promyelocytic leukemia,27 and acute lymphoblastic leukemia.28 Parenchymal involvement was a key feature of all four cases. In contrast, our patient's intracranial infection was localized primarily to the extra-axial cisternal spaces and occurred in an immunocompetent patient.

The treatment of intracranial Fusarium spp infections is best provided with a multidisciplinary approach consisting of surgical intervention and antifungal therapy. Operative resection is essential for debulking of the mass for symptom relief as well as identification of the fungal species.27 Once the fungus is identified, antifungal therapy can be initiated. Amphotericin B and itraconazole have long been the standard antifungal therapy, but these have been reported to have little effect against Fusarium spp. A 2008 study by Espinel-Ingroff et al measuring microbiologically influenced corrosion suggested that voriconazole has a wide susceptibility range against Fusarium. 35 More recent case studies have suggested the combination of voriconazole with terbinafine for successful therapy against fusariosis.36

We initiated triple therapy with amphotericin B, voriconazole, and terbinafine upon identification of the intracranial fungus to cover the broad range of branching septated fungi. After confirmation of the Fusarium organism and due to several hematologic and constitutional side effects, our patient was deescalated to voriconazole monotherapy. She has continued with this therapy since our last follow-up with significant symptomatic and neuroimaging improvement.

Our patient had no known risk factors or associated conditions that would predispose her to a suppressed immune system. Even at outpatient follow-up, it was noted that her immune function was appropriate, and notwithstanding her intracranial fungal abscess, she continued to be in otherwise good health.

Conclusion

We present the first reported case of a Fusarium brain abscess in an immunocompetent patient without any known predisposing health conditions or prior trauma history. Invasive Fusarium spp infection in immunocompetent patients is exceedingly uncommon, and identification of the fungus is necessary to initiate appropriate therapy. Successful treatment of this case was accomplished through both surgical debulking and antifungal drug therapy with excellent short-term results.

References

- 1.Booth C. Kew, UK: Commonwealth Mycology Institute; 1971. The Genus Fusarium. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson P E, Dignani M C, Anaissie E J. Taxonomy, biology, and clinical aspects of Fusarium species. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1994;7(4):479–504. doi: 10.1128/cmr.7.4.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta A K, Baran R, Summerbell R C. Fusarium infections of the skin. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2000;13(2):121–128. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200004000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dignani M C, Anaissie E. Human fusariosis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004;10 01:67–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1470-9465.2004.00845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walsh T J, Groll A, Hiemenz J, Fleming R, Roilides E, Anaissie E. Infections due to emerging and uncommon medically important fungal pathogens. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004;10 01:48–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1470-9465.2004.00839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Musa M O, Al Eisa A, Halim M. et al. The spectrum of Fusarium infection in immunocompromised patients with haematological malignancies and in non-immunocompromised patients: a single institution experience over 10 years. Br J Haematol. 2000;108(3):544–548. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.01856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Donnell K, Sutton D A, Rinaldi M G. et al. Internet-accessible DNA sequence database for identifying Fusaria from human and animal infections. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48(10):3708–3718. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00989-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Epstein A B. In the aftermath of the Fusarium keratitis outbreak: what have we learned? Clin Ophthalmol. 2007;1(4):355–366. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pflugfelder S C, Flynn H W Jr, Zwickey T A. et al. Exogenous fungal endophthalmitis. Ophthalmology. 1988;95(1):19–30. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(88)33229-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hwang S M, Suh M K, Ha G Y. Onychomycosis due to nondermatophytic molds. Ann Dermatol. 2012;24(2):175–180. doi: 10.5021/ad.2012.24.2.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moreno G, Arenas R. Other fungi causing onychomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28(2):160–163. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Romano C, Caposciutti P, Ghilardi A, Miracco C, Fimiani M. A case of primary localized cutaneous infection due to Fusarium oxysporum. Mycopathologia. 2010;170(1):39–46. doi: 10.1007/s11046-010-9290-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yan X, Yu C, Shi Z, Wang S, Zhang F. Nasal cutaneous infection in a healthy boy caused by Fusarium moniliforme. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30(4):e43–e45. doi: 10.1111/pde.12054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Unal A, Kocyigit I, Sipahioglu M H, Tokgoz B, Oymak O, Utas C. Fungal peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis: an analysis of 21 cases. Int Urol Nephrol. 2011;43(1):211–213. doi: 10.1007/s11255-010-9763-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jossi M, Ambrosioni J, Macedo-Vinas M, Garbino J. Invasive fusariosis with prolonged fungemia in a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: case report and review of the literature. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14(4):e354–e356. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edupuganti S, Rouphael N, Mehta A. et al. Fusarium falciforme vertebral abscess and osteomyelitis: case report and molecular classification. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49(6):2350–2353. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02547-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sierra-Hoffman M, Paltiyevich-Gibson S, Carpenter J L, Hurley D L. Fusarium osteomyelitis: case report and review of the literature. Scand J Infect Dis. 2005;37(3):237–240. doi: 10.1080/00365540410021036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charles J F, Eberle C, Daikh D I, Rooney T. Resolution of recurrent Fusarium arthritis after prolonged antifungal therapy. J Clin Rheumatol. 2011;17(1):44–45. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e318205669d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gradon J D, Lerman A, Lutwick L I. Septic arthritis due to Fusarium moniliforme. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12(4):716–717. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.4.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jakle C, Leek J C, Olson D A, Robbins D L. Septic arthritis due to Fusarium solani. J Rheumatol. 1983;10(1):151–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wadhwani K, Srivastava A K. Fungi from otitis media of agricultural field workers. Mycopathologia. 1984;88(2-3):155–159. doi: 10.1007/BF00436447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Macêdo D P, Neves R P, Fontan J, Souza-Motta C M, Lima D. A case of invasive rhinosinusitis by Fusarium verticillioides (Saccardo) Nirenberg in an apparently immunocompetent patient. Med Mycol. 2008;46(5):499–503. doi: 10.1080/13693780701861462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park A H, Muntz H R, Smith M E, Afify Z, Pysher T, Pavia A. Pediatric invasive fungal rhinosinusitis in immunocompromised children with cancer. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;133(3):411–416. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gorman S R, Magiorakos A-P, Zimmerman S K, Craven D E. Fusarium oxysporum pneumonia in an immunocompetent host. South Med J. 2006;99(6):613–616. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000217160.63313.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agamanolis D P, Kalwinsky D K, Krill C E Jr, Dasu S, Halasa B, Galloway P G. Fusarium meningoencephalitis in a child with acute leukemia. Neuropediatrics. 1991;22(2):110–112. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1071428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anaissie E, Kantarjian H, Ro J. et al. The emerging role of Fusarium infections in patients with cancer. Medicine (Baltimore) 1988;67(2):77–83. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198803000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anten S, Heddema E R, Visser O, Zweegman A S. Images in haematology. Cerebral fungal abscess in a patient with acute promyelocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2008;140(3):253. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Antunes N L, Hariharan S, DeAngelis L M. Brain abscesses in children with cancer. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1998;31(1):19–21. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-911x(199807)31:1<19::aid-mpo4>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boutati E I, Anaissie E J. Fusarium, a significant emerging pathogen in patients with hematologic malignancy: ten years' experience at a cancer center and implications for management. Blood. 1997;90(3):999–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Medeiros B C, de Medeiros C R, Werner B. et al. Central nervous system infections following bone marrow transplantation: an autopsy report of 27 cases. J Hematother Stem Cell Res. 2000;9(4):535–540. doi: 10.1089/152581600419215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kleinschmidt-Demasters B K. Disseminated Fusarium infection with brain abscesses in a lung transplant recipient. Clin Neuropathol. 2009;28(6):417–421. doi: 10.5414/npp28417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Njambi S, Huttova M, Kovac M, Freybergh P F, Bauer F, Muli J M. Fungal neuroinfections: rare disease but unacceptably high mortality. Neuroendocrinol Lett. 2007;28 02:25–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pagano L, Caira M, Falcucci P, Fianchi L. Fungal CNS infections in patients with hematologic malignancy. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2005;3(5):775–785. doi: 10.1586/14787210.3.5.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steinberg G K, Britt R H, Enzmann D R, Finlay J L, Arvin A M. Fusarium brain abscess. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1983;58(4):598–601. doi: 10.3171/jns.1983.58.4.0598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Espinel-Ingroff A, Johnson E, Hockey H, Troke P. Activities of voriconazole, itraconazole and amphotericin B in vitro against 590 moulds from 323 patients in the voriconazole phase III clinical studies. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61(3):616–620. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Inano S, Kimura M, Iida J, Arima N. Combination therapy of voriconazole and terbinafine for disseminated fusariosis: case report and literature review. J Infect Chemother. 2013;19(6):1173–1180. doi: 10.1007/s10156-013-0594-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]