ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Little is known about older women’s experience with a benign breast biopsy.

OBJECTIVES

To examine the psychological impact and experience of women ≥ 65 years of age with a benign breast biopsy.

DESIGN

Prospective cohort study using quantitative and qualitative methods.

SETTING

Three Boston-based breast imaging centers.

PARTICIPANTS

Ninety-four English-speaking women ≥ 65 years without dementia referred for breast biopsy as a result of an abnormal mammogram, not aware of their biopsy results at baseline, and with a subsequent negative biopsy.

MEASUREMENTS

We interviewed women at the time of breast biopsy (before women knew their results) and 6 months post-biopsy. At both interviews, participants completed the validated negative psychological consequences of screening mammography questionnaire (PCQ, scores range from 0 to 36 [high distress], PCQ ≥ 1 suggests a psychological consequence, PCQs <1 are reported at time of screening) and women responded to open-ended questions about their experience. At follow-up, participants described the quality of information received after their benign breast biopsy. We used a linear mixed effects model to examine if PCQs declined over time. We also reviewed participants’ open-ended comments for themes.

RESULTS

Overall, 88 % (83/94) of participants were non-Hispanic white and 33 % (31/94) had a high-school degree or less. At biopsy, 76 % (71/94) reported negative psychological consequences from their biopsy compared to 39 % (37/94) at follow-up (p < 0.01). In open-ended comments, participants noted the anxiety (29 %, 27/94) and discomfort (28 %, 26/94) experienced at biopsy (especially from positioning on the biopsy table). Participants requested more information to prepare for a biopsy and to interpret their negative results. Forty-four percent (39/89) reported at least a little anxiety about future mammograms.

CONCLUSIONS

The high psychological burden of a benign breast biopsy among older women significantly diminishes with time but does not completely resolve. To reduce this burden, older women need more information about undergoing a breast biopsy.

KEY WORDS: older women, breast biopsy, anxiety

INTRODUCTION

Women ≥ 65 years of age are the fastest growing segment of the US population and the incidence of breast cancer increases with age. Mammography is estimated to decrease breast cancer mortality by 15–25 % for women 50–74 years; however, none of the randomized controlled trials included women aged 75 and older.1–3 Mammography is generally recommended to older women with greater than 10-year life expectancy.4 In 1991, Medicare instituted coverage of mammography screening for all women aged 65 and older, and since then, screening rates have risen rapidly among older women. Currently, 60–70 % of women aged 65–74 years and 56 % of women aged 75 and older are regularly screened with mammography.5,6 However, 10–20 % of women ≥ 65 years who are screened will experience a false-positive mammogram and around 25 % of those who experience a false-positive mammogram will undergo a benign breast biopsy.7,8 While it is well known that undergoing a breast biopsy is stressful for younger women, it is not known how this experience affects older women.9–14 To better understand and improve older women’s experience with a benign breast biopsy, we interviewed women aged 65 and older at the time of breast biopsy before they knew their results and 6 months later if not diagnosed with breast cancer. We used both quantitative and qualitative methods to better understand and to develop a conceptual framework of older women’s experience with a benign breast biopsy.

DESIGN AND METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a longitudinal study to examine the psychological impact of a benign breast biopsy among women ≥ 65 years. Between August 2007 and December 2011, we interviewed English speaking older women without dementia (determined by problem list and/or primary care physician [PCP]) at the time of breast biopsy but before women knew the results of their biopsy, and 6 months post-biopsy. This study was restricted to women who were not diagnosed with breast cancer or ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), confirmed by pathology reports.

Participants

We recruited women from the breast imaging centers at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC), Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH), and Boston Medical Center (BMC). An administrator at each site provided research staff with the names of women ≥ 65 years scheduled for breast biopsy. Since we aimed to include numbers of women ≥ 75 years similar to those of women 65–74 years, we recruited women ≥ 75 years continuously and women 65–74 years every third week. We did not recruit women during staff vacations. Women were contacted for this study by 1) telephone if their PCPs gave permission, or 2) in the waiting room at the time of the breast biopsy. Research assistants administered the initial interview over the telephone or in person at the time of the breast biopsy (depending on participants’ preferences). All follow-up interviews were administered over the telephone. Participants gave verbal informed consent. The Institutional Review Board at each site approved this study.

Data Collection

At biopsy, we asked participants about use of mammography screening, personal or family history of breast cancer, and history of breast biopsy. We also assessed educational attainment, social support (Medical Outcomes Study tangible support scale),15 life expectancy (Schonberg mortality index, scores of ten or more indicate ≤ 9-year life expectancy),16 marital status, living arrangement, geography, and race/ethnicity.

Quantitative Outcomes

We assessed the following outcomes at biopsy and at 6-months follow-up:

Psychological Consequence Questionnaire (PCQ): The PCQ is a 12-item validated index that provides information about the psychological consequences of a threat of breast cancer as a result of undergoing mammography.17 It measures how thoughts and feelings about breast cancer impact one’s emotional, social, and/or physical functioning. Each item is measured on a four-point scale from 0 “not at all” to 3 “quite a lot of the time.” Scores range from 0 to 36 (mean scores < 1 are reported in the literature at time of mammography screening).9 The PCQ has been shown to correlate highly with other measures of anxiety during the period between an abnormal mammogram and during the waiting for additional test results.18 It may be analyzed as a continuous measure or dichotomized as 0 vs. ≥ 1 (indicating a negative psychological consequence).9,19 We present both continuous and dichotomous results.

Mood/Worry: We asked participants about the impact of worries about breast cancer on mood and daily activities using questions used in studies of younger women: 1) “How much of the time is your mood made worse because of worrying about breast cancer?” and 2) “How much of the time has worrying about breast cancer interfered with your daily activities?” Both are scored on a four-point Likert scale from “not at all” (0) to “a lot” (3).20,21

General health: We asked women about their general health using the SF-12 physical (PCS) and mental components scales (MCS).22

At follow-up, we also assessed:

Information received: To learn older women’s perceptions of the information they received after their breast biopsy, we asked four questions previously used in a study of younger women.23 The questions assess: 1) the amount of information received about breast cancer, and whether the information was 2) understandable, 3) reassuring, and/or 4) whether it caused worry.23

Concerns about breast cancer: We asked previously developed questions on how much anxiety participants now have about the results of future mammograms (0 = none to 4 = a lot), and whether their concerns about breast cancer have increased, decreased, or not changed.20

Qualitative Component

At biopsy, we asked women to describe the role of family/friends in their medical decision-making after their abnormal mammogram. At the end of both interviews, we asked women if they had any other thoughts or comments about their experience after their abnormal mammogram. Research assistants wrote down participants’ answers to these questions verbatim, and noted any additional comments made by participants related to their experience at any point during the interviews.

Analyses

Quantitative Outcomes

We used bivariable statistics to compare participants’ sociodemographic characteristics by age (65–74 vs. 75+ years). We used linear mixed effects models to examine if PCQ, anxiety about breast cancer, or SF-12 PCS and MCS declined over time. We adjusted our models by age, educational attainment (college vs. high-school or less), life expectancy, personal or family history of breast cancer, and history of benign breast biopsy.24,25 In addition, we examined the linear contrast term from the linear mixed effects model to determine if PCQ differed at either time by age, life expectancy, personal or family history of breast cancer, or history of benign breast biopsy. Missing values for the PCQ were imputed according to standard guidelines. Specifically, if there was only one item missing from a PCQ subscale (emotional, social, physical), then the mean of the other items in that subscale for that individual was substituted.17,25 Imputed data were entered for two women at baseline and three women at follow-up. We also compared perceptions of information received after a breast biopsy by age and by diagnosis (atypia vs. no atypia). All statistical analyses used SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Qualitative Component

For qualitative analyses, we combined each participant’s open-ended comments into one document. Using grounded theory, one investigator (MAS) analyzed the data line-by-line to label concepts and to define and develop codes based on the concepts.26,27 Three investigators (ERM, RAS, JD) then used the code dictionary to recode participants’ comments reviewing the transcripts line-by-line. Based on consensus, three additional codes were added after this review. One investigator (MAS) recoded participants’ comments using the newly identified codes and reviewed the coding of the other investigators. If at least two investigators labeled a comment with a code, then the code was applied to that comment. We used the same code dictionary for both interviews since women could comment on their pre-biopsy experience and/or their experience the day of biopsy during either interview. We combined codes to identify major themes based on consensus.

To best represent what we learned from our analyses, we developed a conceptual framework. To create the framework, the investigative team, which included geriatricians, internists, breast imagers, and health services researchers, discussed how the themes identified in our qualitative analyses interacted to impact older women’s experience at breast biopsy. We also discussed whether there were important findings from the quantitative analyses that needed to be included in the model. Each investigator analyzed and agreed on the validity of the final model.

RESULTS

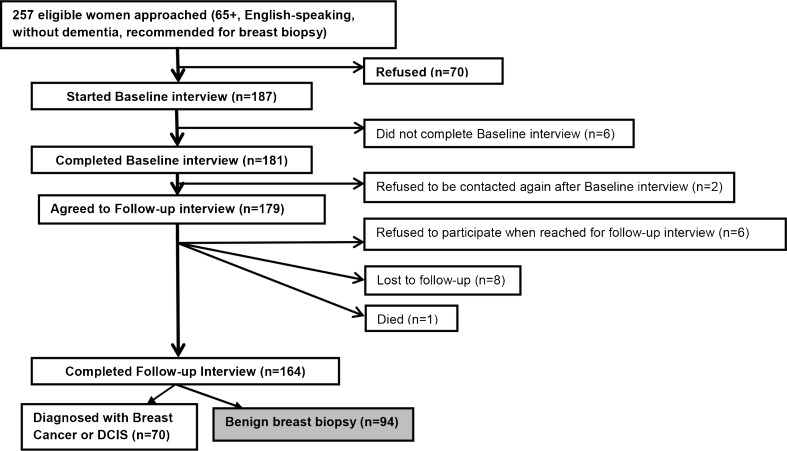

Sample Population (Fig. 1)

Figure 1.

Study sample.

A total of 164 women completed both interviews (64 % of eligible women); 70 were diagnosed with breast cancer. Therefore, our final sample includes 94 women who underwent a benign breast biopsy.

Table 1 describes our sample characteristics. Mean age of the population was 74.1 years (standard deviation [SD] +/− 6.0 years). Overall, 88 % (n = 83) were non-Hispanic white and 33 % (n = 30) had a high-school degree or less. The majority (89 %, n = 84) underwent screening annually and 20 % (n = 19) had a history of breast cancer. Women ≥ 75 years were more likely than women 65–74 years to have had a past breast biopsy, to have ≤ 9-year life expectancy, and to need more emotional support than they were currently receiving.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Overall (n = 94) % (n)* | 65–74 years (n = 56, 60 %) % (n)* | 75+ years (n = 38, 40 %) % (n)* | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | 0.12 | |||

| High-school or less | 33 % (31) | 27 % (15) | 42 % (16) | |

| Some college and beyond | 67 % (63) | 73 % (41) | 58 % (22) | |

| Currently married | 41 % (39) | 46 % (26) | 34 % (13) | 0.24 |

| Lives alone | 51 % (48) | 46 % (26) | 58 % (22) | 0.28 |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.54 | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 88 % (83) | 86 % (48) | 92 % (35) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 11 % (10) | 13 % (7) | 8 % (3) | |

| Other | 1 % (1) | 2 % (1) | 0 | |

| Geography | ||||

| Rural | 14 % (13) | 14 % (8) | 13 % (5) | 0.52 |

| Semi-urban | 51 % (48) | 46 % (26) | 58 % (22) | |

| Urban | 33 % (35) | 39 % (22) | 29 % (11) | |

| Gets annual mammogram | 89 % (84) | 88 % (49) | 92 % (35) | 0.48 |

| History of invasive or non-invasive breast cancer | 20 % (19) | 21 % (12) | 18 % (7) | 0.72 |

| History of benign breast biopsy | 34 % (32) | 25 % (14) | 47 % (18) | 0.02 |

| Family history of breast cancer | 20 % (19) | 20 % (11) | 21 % (8) | 0.87 |

| ≤ 9 year remaining life expectancy† | 22 % (21) | 9 % (5) | 42 % (16) | < 0.001 |

| Breast imaging site | ||||

| Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center | 66 % (62) | 68 % (38) | 63 % (24) | 0.29 |

| Brigham and Women’s | 28 % (26) | 23 % (13) | 34 % (13) | |

| Boston Medical Center | 6 % (6) | 9 % (5) | 3 % (1) | |

| Tangible social support (mean, SD, range 4–20 [none to all the time])‡ | 17.0 (+/−3.9) | 17.0 (+/−4.2) | 17.1 (+/−3.6) | 0.87 |

| Needs more help with daily tasks | 13 % (12) | 13 % (7) | 13 % (5) | 0.93 |

| Needs more emotional support | 18 % (17) | 25 % (14) | 8 % (3) | 0.03 |

| Pathology | ||||

| Atypical ductal hyperplasia | 7 % (7) | 9 % (5) | 5 % (2) | 0.28 |

| Fibroadenoma | 23 % (22) | 18 % (10) | 32 % (12) | |

| Other benign | 69 % (65) | 73 % (41) | 63 % (24) | |

| Type of biopsy | ||||

| Stereotactic core biopsy | 60 % (56) | 59 % (33) | 61 % (23) | 0.15 |

| Ultrasound guided core biopsy | 35 % (33) | 32 % (18) | 39 % (15) | |

| Other | 5 % (5) | 9 % (5) | 0 | |

| Baseline interview conducted in person the day of the biopsy (rather than over the telephone) | 18 % (17) | 20 % (11) | 16 % (6) | 0.63 |

| Median follow-up time (months, interquartile range) | 5.6 (5.1–6.3) | 5.6 (5.0–6.1) | 5.8 (5.3–6.4) | 0.34 |

Quantitative Outcomes

Table 2 presents the psychological impact of a benign breast biopsy over time by participant age. Psychological outcomes are presented both categorically (any impact vs. none) and as means of continuous scores. Overall, 76 % (n = 71) of women reported experiencing a negative psychological consequence at the time of breast biopsy and 39 % (n = 37) at follow-up; there were no significant differences by age, personal or family history of breast cancer, or history of benign breast biopsy (Table 3). Women with ≤ 9 year life expectancy tended to be more likely to report negative psychological consequences at follow-up (mean PCQ 2.4 [+/−3.9]) than women with longer life expectancy (mean PCQ 1.1 [+/−1.9]), but the results were not statistically significant (p = 0.08). Psychological consequences declined significantly over time. In multivariable analyses, women with ≤ 9-year life expectancy (p = 0.07) and those with lower educational attainment (p = 0.09) tended to be more likely to report psychological burden from their biopsy, and the effects were constant over time but did not reach statistical significance. There were no significant differences in SF-12 MCS scores over time; however, SF-12 PCS scores declined significantly over time.

Table 2.

Impact of a Benign Breast Biopsy over Time by Age

| 65–74 (n = 56) | 75+ (n = 38) | p value (group difference)* | 65–74 (n = 56) | 75+ (n = 38) | p Group difference† | Adjusted p ‡ (change with time) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | % (n) | Mean (Standard Deviation) | Mean (Standard Deviation) | ||||

| Psychological Consequences (PCQ)- total§ | |||||||

| At breast biopsy | 77 % (43) | 74 % (28) | 0.73 | 4.3 (4.3) | 5.1 (5.7) | 0.78 | |

| 6 months later | 38 % (21) | 42 % (16) | 0.66 | 1.2 (2.3) | 1.6 (2.9) | 0.81 | < 0.001 |

| How much of the time is your mood made worse because of worrying about breast cancer? (0 = not at all to 4 = a lot of the time) | |||||||

| At breast biopsy | 36 % (20) | 34 % (13) | 0.88 | 1.5 (0.7) | 1.7 (1.0) | 0.53 | |

| 6 months later | 16 % (9) | 26 % (10) | 0.22 | 1.2 (0.5) | 1.3 (0.5) | 0.88 | 0.001 |

| How much of the time has worrying about breast cancer interfered with your daily activities? (0 = not at all to 4 = a lot of the time) | |||||||

| At breast biopsy | 50 % (28) | 42 % (16) | 0.45 | 1.8 (0.9) | 1.7 (0.9) | 0.34 | |

| 6 months later | 25 % (14) | 21 % (8) | 0.66 | 1.3 (0.6) | 1.3 (0.7) | 0.46 | 0.001 |

| SF-12 physical component score‖ | |||||||

| At breast biopsy | NA | NA | 50.5 (10.2) | 48.7 (10.2) | 0.18 | ||

| 6 months later | NA | NA | 47.4 (11.7) | 47.3 (11.6) | 0.14 | 0.03 | |

| SF-12 mental component score‖ | |||||||

| At breast biopsy | NA | NA | 45.3 (7.9) | 45.2 (8.3) | 0.97 | ||

| 6 months later | NA | NA | 44.3 (8.8) | 47.0 (7.6) | 0.16 | 0.73 | |

Participants were unaware of their biopsy results at this time

*We used chi-square statistics at each time point to compare presence of a negative psychological consequence of breast biopsy by age. We dichotomized women who reported any psychological consequence (PCQ of 1 or more or any impact of breast cancer worries on mood or daily activities) compared to none

†We examined the linear contrast term from the linear mixed effects models to determine if mean scores on these outcomes differed at each time point by age

‡These p values are from linear mixed effect models examining the effect of time on each outcome (adjusting for age, education, life expectancy, personal and family history of breast cancer, and history of benign breast biopsy)

§The Psychological Consequences Questionnaire (PCQ) is a 12-item validated index that provides information about the psychological consequences of a threat of breast cancer as a result of undergoing mammography.16 Each item is measured on a four-point scale from 0 “not at all” to 3 “quite a lot of the time.” Scores range from 0 to 36; higher score indicate greater psychological distress

‖SF-12 norms for the general US population are: 1) for Mental Component Score (MCS): 53.5 (Standard Deviation [SD] +/−10.94) for adults ≥ 75 years and 55.3 for adults 65–74 years; and 2) for Physical Component Score (PCS): 38.7 for adults ≥ 75 years and 46.4 for adults 65–74 years.21 Lower scores indicate worse health

Table 3.

Psychological Consequences of a Benign Breast Biopsy Over Time by Life Expectancy, Personal or Family History of Breast Cancer, and History of Benign Breast Biopsy

| > 9-year life expectancy n = 73† | ≤ 9-year life expectancy n = 21† | p value‡ | > 9 years n = 73 | ≤ 9 years n = 21 | p value§ | |

| Psychological Consequences (PCQ)- total* | ||||||

| At breast biopsy | 77 % (56) | 71 % (25) | 0.62 | 4.3 (4.6) | 5.8 (5.6) | 0.25 |

| 6 months later | 37 % (20) | 48 % (10) | 0.38 | 1.1 (1.9) | >2.4 (3.9) | 0.08 |

| History of breast cancer n = 19† | No history of breast cancer n = 75† | History of breast cancer n = 19 | No history of breast cancer n = 75 | |||

| Psychological Consequences (PCQ)- total* | ||||||

| At breast biopsy | 73 % (14) | 76 % (57) | 0.83 | 4.1 (4.1) | 4.8 (5.1) | 0.52 |

| 6 months later | 37 % (7) | 40 % (30) | 0.80 | 1.4 (2.4) | 1.4 (2.6) | 0.95 |

| Family history n = 19† | No family history n = 75† | Family history n = 19 | No family history n = 75 | |||

| Psychological Consequences (PCQ)- total* | ||||||

| At breast biopsy | 68 % (13) | 77 % (58) | 0.42 | 4.5 (5.0) | 4.7 (5.0) | 0.93 |

| 6 months later | 37 % (7) | 40 % (30) | 0.80 | 1.2 (1.8) | 1.4 (2.7) | 0.70 |

| History of benign breast biopsy n = 32† | No history of benign breast biopsy n = 62† | History of benign breast biopsy n = 32 | No history of benign breast biopsy n = 62 | |||

| Psychological Consequences (PCQ)- total* | ||||||

| At breast biopsy | 78 % (32) | 74 % (46) | 0.67 | 4.5 (4.5) | 4.7 (5.1) | 0.77 |

| 6 months later | 31 % (10) | 44 % (27) | 0.25 | 1.1 (2.0) | 1.5 (2.8) | 0.46 |

Participants were unaware of their biopsy results at this time

*The Psychological Consequences Questionnaire (PCQ) is a 12-item validated index that provides information about the psychological consequences of a threat of breast cancer as a result of undergoing mammography.16 Each item is measured on a four-point scale from 0 “not at all” to 3 “quite a lot of the time.” Scores range from 0 to 36; higher score indicate greater psychological distress

†These analyses refer to women who reported any negative psychological consequence (PCQ of 1 or more)

‡We used chi-square statistics at each time point to compare presence of a negative psychological consequence by life expectancy, family or personal history of breast cancer, or history of breast biopsy

§We examined the linear contrast term from the linear mixed effects model to determine if mean PCQs differed by age, life expectancy, family or personal history of breast cancer, or history of breast biopsy

Information Received

At biopsy, 48 % (n = 45) of women reported that they spoke or planned to speak with their PCP about their abnormal mammogram. Most women (84 %, n = 79) were satisfied with the amount of information they received after their biopsy; 77 % (72 of 93) found the information completely understandable; and 58 % (50 of 86) found the information very reassuring. However, 40 % (37 of 92) reported that the information made them worry. Nearly half (44 %, 39 of 89) of women reported that they now had at least a little anxiety about the results of future mammograms and 26 % [23 of 89]) reported that their concerns about breast cancer had increased. There were no differences by age in perceptions of information received after a breast biopsy (data in Appendix). Women diagnosed with atypia tended to be more likely to report anxiety about future mammograms than women without atypia (67 % [2/6] vs. 42 % [35/83], p = 0.24).

Qualitative Outcomes

Table 4 presents the number of women that noted each theme in open-ended comments and example quotes. Overall, 27 women (29 %) commented on the anxiety they experienced at breast biopsy, especially women with a personal or family history of breast cancer. Twenty-six women (28 %) commented on the discomfort they experienced at breast biopsy. Eleven (12 %) specifically mentioned the positioning on the biopsy table as being particularly uncomfortable and even exacerbating their arthritis; all women who made this comment underwent a stereotactic core biopsy.

Table 4.

Themes Identified about Older Women’s Breast Biopsy Experience in Qualitative Analyses

| Theme | Frequency n = 94 | Quotations |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional response | ||

| Anxiety | 27 | Before [biopsy], I had anxiety and sleepless nights. |

| Affected by: | ||

| 1) family history | 9 | I have a family history so I got anxious. |

| 2) breast cancer history | 4 | I had breast cancer before so I am frightened. |

| 3) History of biopsy | 4 | I have been through it before, it didn’t faze me. |

| Traumatic | 8 | A traumatic experience, I don’t want to go through it again. |

| Not bothered | 11 | I wasn’t concerned. |

| Biopsy uncomfortable | 26 | I had lots of trouble with the biopsy. It was very difficult. |

| Positioning | 11 | I was in a very uncomfortable position because of arthritis. |

| Medical system | ||

| Faith in doctor | 27 | I took the attitude that I have the best doctors. |

| PCP involvement | 7 | I didn’t even talk to my primary care doctor. |

| Faith in hospital | 10 | I feel very confident with this hospital. |

| Radiology staff and physicians | ||

| Positive | 28 | Everyone was very professional, compassionate. It alleviated anxiety. The staff complained that they could not get close enough because I was short. |

| Negative | 9 | |

| Dissatisfied with information | 13 | Never told what type of biopsy I would have. |

| Decision-making | ||

| Patient makes decisions | 29 | I like to make my own decisions. |

| Does not want to burden family | 18 | It all depends on how serious it is for me to tell my family. |

| Challenging waiting for results | 20 | Not knowing is the hardest part. |

| Coping mechanisms | ||

| Positive thinking | 20 | I’m going to think positively until I hear. |

| Spirituality | 14 | My faith gets me through. |

| Interpersonal | ||

| Family/friend support: | 46 | My daughter helps as an advisor. |

| Family/friend with experience | 8 | Many friends have had breast cancer, I rely on them. |

| Family friend in medicine | 13 | My daughter is a nurse, I will rely on her. |

| Transportation | 5 | My husband drives me to appointments. |

| Internet | 6 | I found information on the internet. |

| Diversionary | 12 | I try to focus on more beautiful things. |

| Avoidance | 6 | They asked me to come back immediately, but I was busy. |

| Competing issues | ||

| Health | 24 | I am surprised that a lot of attention is focused on breast biopsy instead of other problems. |

| Loss of spouse | 4 | If my husband hadn’t died I would be fighting much harder to get this cleared up immediately. |

| Caretaking | 6 | I’m his [husband’s] primary care giver, so that places a huge burden on me. |

| Age | 14 | The older you get, the more it affects you. |

| Anxiety about future tests | 12 | It is worrisome I have to come back every 6 months for 2 years. |

| Commitment to mammography | 11 | Mammograms are always good. I will always get them. |

| Ways to improve | ||

| Better information | 17 | There wasn’t really any information after the biopsy. |

| Emotion after learning results* | ||

| Relief | 21 | I felt relieved. |

| Happy | 27 | I was quite thrilled. |

| Grateful | 5 | I felt very grateful. |

*The themes reported under the heading “Emotion after learning results” were only abstracted from follow-up interviews. All other themes were abstracted from either interview

Faith in one’s physicians (n = 28, 30 %) and/or hospital (n = 10, 11 %) and empathetic staff and physicians at the breast imaging centers (n = 28, 30 %) helped reduce anxiety. Conversely, less thoughtful staff (n = 9, 10 %) and/or lack of information (n = 13, 14 %) on what to expect at biopsy or on how the biopsy may affect other medical conditions exacerbated worries.

Twenty women (21 %) noted that it was challenging waiting for the results of their biopsy and described using several coping strategies. Most commonly, these women sought support from family or friends (46, 49 %), especially family/friends with past experience with a breast biopsy (n = 8, 9 %) or those that were health professionals (n = 13, 14 %). However, 18 women (19 %) mentioned that they did not want to worry family or friends until they knew their results; 13 (72 %) of the women that made this comment were ≥ 75 years. Thirteen participants (14 %) felt that they were as affected or even more affected by their biopsy because of their age. Participants also noted that the biopsy was only one of several competing health (n = 24, 26 %) or social issues (n = 10, 11 %) affecting their quality of life.

After learning their biopsy was negative, women reported feeling relieved (n = 21, 22 %), happy (n = 27, 29 %), and grateful (n = 6, 6 %). However, 11 women (12 %) noted confusion about the implications of their “negative” results and anxiety about future mammograms. To improve their experience, women requested better information about what to expect at breast biopsy and the meaning of their negative results (n = 17, 18 %).

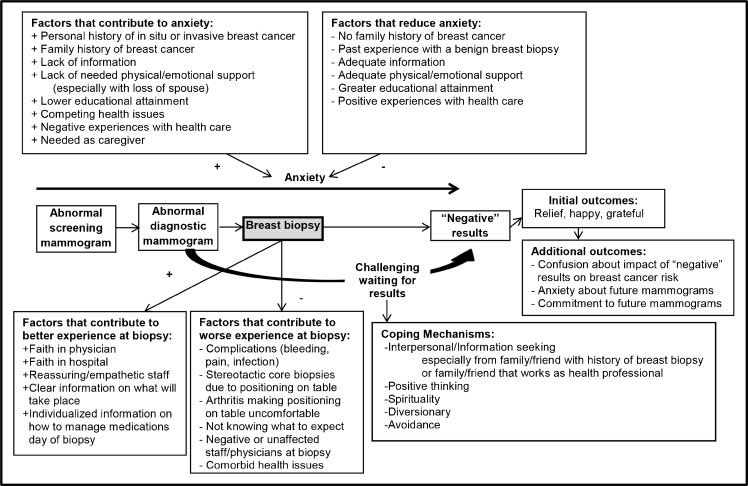

Conceptual Framework (Fig. 2)

Figure 2.

Conceptual framework of older women's experience with a benign breast biopsy.

In Figure 2, we present factors that interact to enhance or worsen older women’s experience with a breast biopsy and which patient experiences (e.g., history of biopsy) and characteristics (e.g., educational attainment) affect older women’s anxiety around a breast biopsy.

DISCUSSION

Undergoing a benign breast biopsy after an abnormal screening mammogram is highly stressful for women ≥ 65 years. Although the psychological burden of a benign breast biopsy declines significantly within 6 months, 39 % of older women continue to report at least one negative psychological consequence of undergoing a benign breast biopsy 6 months later and 44 % report anxiety about future mammograms. To improve older women’s experience with a breast biopsy, older women need to be well informed of: 1) what to expect the day of biopsy; 2) how to manage their other medications before a biopsy; 3) the impact of the biopsy on their chronic medical conditions; and 4) the impact of a negative result on their breast cancer risk. Multilevel interventions are needed to improve older women’s experience with a breast biopsy.

Prior studies have generally found that premenopausal women experience more anxiety at the time of breast biopsy than postmenopausal women;10–12,14,28–32 however, few studies have included women aged ≥ 65 years.13,33–35 Studies of older women diagnosed with breast cancer have found that older women may have more difficulty adjusting to a breast cancer diagnosis than younger postmenopausal women, due to increased comorbidity,36frailty,37 declining social networks,38,39 less access to medical information,40 decreased use of counseling,41 more experience with loss,41–43 and lower socioeconomic status.44 Older women in our study noted that these factors also affected their experience with a breast biopsy.

We found that 26 % of older women reported that their concerns about breast cancer had increased after their breast biopsy. Previous studies have found that 33 to 63 % of women report increased concerns about breast cancer after a false-positive mammogram.12,21,45 Our numbers may be slightly lower due to the age of our participants and that 35 % had experienced a benign breast biopsy before. In addition, older women diagnosed with atypia tended to report more anxiety about future mammograms. Although atypia is a known risk factor for breast cancer, few have examined the effect of atypia on late-life breast cancer risk.46 One study of 82 women ≥ 70 years found no association between atypia and breast cancer risk,47 and others have found that the risk associated with atypia may be greater for premenopausal women.46 Research is needed to better understand the importance of atypia as a risk factor for late-life breast cancer to better inform older women and potentially reduce their anxiety.

To improve older women’s experience at breast biopsy, it may be important for breast imaging staff to inform older women how long they may spend on the biopsy table and that some women find the positioning uncomfortable, particularly those undergoing stereotactic core biopsies. The biopsy table was designed to access every part of the breast and not necessarily to ensure the comfort of older women, especially those with arthritis. How to make older women more comfortable during a breast biopsy warrants further study; however, strategic placement of towels and pillows may be important. As noted by our study participants, older women also benefit from reassuring and positive staff and physicians at breast biopsy.

To help reduce older women’s distress before and after a breast biopsy, health systems may want to encourage older women to contact their PCPs for informational and emotional support, especially since only 48 % of participants planned to speak to their PCP during this highly stressful period. While women diagnosed with breast cancer are given a substantial amount of information, studies have found that women diagnosed with benign conditions may be given less information and/or be dismissed as having an inconsequential problem.18 Study participants requested clear information about what their negative results mean and the impact on their breast cancer risk. Future studies should further examine what content and format of information older women would like to receive before and after a breast biopsy to improve their experience.

Since many women in our study found it challenging waiting for the results of their biopsy, the more quickly women can be informed of their results the better. Breast biopsies could possibly be performed early in a week so that pathologists can review the breast tissue and women can be informed of the results before a weekend delay. Systems should be in place to alert clinicians as quickly as possible as to when results are available so that there is little delay in informing patients of their results. In this context, it may be helpful for clinicians to telephone patients with their results with a follow-up clinic appointment when necessary.

Many women in our study reported seeking emotional and information support from family or friends. However, some older women, particularly those ≥ 75 years, noted that they try to keep their concerns to themselves so as not to burden family members. Meanwhile, women with ≤ 9-year life expectancy, the majority of which were ≥ 75 years, tended to be more likely to report a negative psychological consequence of breast biopsy at follow-up. Therefore, it may be important for clinicians to encourage older women, particularly those in poor health, to discuss their breast biopsy with family or friends. Since women ≥ 75 years were more likely to report lack of available emotional support, it may also be particularly important for systems of care to connect these women with their health professionals at time of breast biopsy for emotional support. Our findings support data that mammography screening may be more harmful than beneficial to older women with short life expectancy.

Despite their experience with a benign breast biopsy, several women in our study commented on the benefits of mammography and pledged to continue getting screened. None of the participants described any regrets about being screened, despite the fact that 92 % were referred for their biopsy as a direct result. We previously found that a history of a benign breast biopsy strongly influences older women to continue being screened.48 Therefore, it may be important to educate older women with a past history of a benign breast biopsy that they likely experienced a burden of mammography screening to allow these women to make informed decisions about whether or not to continue being screened. In addition, experience with a false-positive mammogram not only increases women’s enthusiasm for screening,49 but may lead to increased health care utilization in general.50 Considering the rising costs of health care and the growing population of older women, future studies should examine the impact of false-positive mammograms and resulting benign breast biopsies on health care utilization among older women.

There are important limitations of this study. First, the geographical and ethnic diversity of the current sample was limited, as we only recruited English-speaking older women from Boston-based breast imaging centers. However, we recruited older women from three diverse sites, including a large safety-net hospital in Boston. Our sample size was small, limiting power for some analyses. Research assistants scribed rather than audio-taped participants’ open-ended comments and some comments may not have been captured. Although we interviewed all women before they knew their biopsy results, the timing of the initial interview (before/after, day of biopsy) could have affected anxiety levels. Strengths of this study include that we focused on an understudied population, women ≥ 65 years, and we collected data prospectively using mixed methods.

In conclusion, older women experience considerable anxiety at the time of breast biopsy. The distress declines significantly within 6 months, but does not return to typical pre-mammogram levels. To improve older women’s experience with a breast biopsy, they need clear information on how to prepare for biopsy, individualized information on what to expect considering their chronic medical issues, and information on how to interpret negative findings. Primary care clinicians and radiologists may need to provide additional support and information to older women during this stressful time period, to improve older women’s satisfaction and experience with breast biopsy.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Rossana Valencia, MPH, Christine Gordon, MPH, and Maria Cecilia Griggs, RN, MPH, for their work recruiting patients to this study. We are also grateful to Elena Morozov at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and Julie Ferragamo and Jane Pietrantonio at Brigham and Women’s Hospital for helping us to identify patients for this study. Written permission has been obtained from all persons named in this acknowledgment. Dr. Schonberg had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Dr. Mara Schonberg was supported by a Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award in Aging supported by the National Institute on Aging K23 [K23AG028584], the John A. Hartford Foundation, the Atlantic Philanthropies, the Starr Foundation, and the American Federation for Aging Research. Dr. Ngo received support from Harvard Catalyst, the Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (NIH Award #UL1 RR 025758 and financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers). Dr. Marcantonio was supported by a Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research from the National Institute on Aging (K24 AG035075). The sponsors had no role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Presentations

This work was presented in part at the Presidential poster session of the 2014 annual meeting of the American Geriatrics Society, 15 May 2014. This work was also presented at the 2014 annual meeting of the New England Region of the Society of General Internal Medicine, 7 March 2014.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Fein-Zachary worked as a consultant for Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Inc., in 2014. All other authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Financial Disclosure Information

This research was supported by a Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award in Aging supported by the National Institute on Aging K23 [K23AG028584], the John A. Hartford Foundation, the Atlantic Philanthropies, the Starr Foundation, and the American Federation for Aging Research. Dr. Marcantonio was supported by a Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research from the National Institute on Aging (K24 AG035075).

Appendix

Table 5.

Perceptions of Information Received After a Breast Biopsy by Age

| Overall (n = 94) % (n)a | 65–74 years (n = 56, 60 %) % (n)a | 75+ years (n = 38, 40 %) % (n)a | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spoke of planned to speak to PCP about abnormal mammogram at baseline | 48 % (45) | 48 % (27) | 47 % (18) | 0.94 |

| Amount of information received after biopsy | ||||

| Too much | 3 % (3) | 0 | 8 % (3) | 0.09 |

| Adequate | 84 % (79) | 86 % (48) | 82 % (31) | |

| Too little | 13 % (12) | 14 % (8) | 11 % (4) | |

| Information received completed understandable | 77 % (72 of 93) | 75 % (42) | 81 % (30 of 37) | 0.56a |

| Information very reassuring | 58 % (50 of 86) | 55 % (28) | 63 % (22) | 0.56a |

| Information caused worry | 40 % (37 of 92) | 40 % (22 of 55) | 41 % (15 of 37) | 0.25a |

| At least a little anxiety about future mammograms | 44 % (39 of 89) | 45 % (24 of 53) | 42 % (15 of 36) | 0.74 |

| Concerns about breast cancer | ||||

| Increased | 26 % (23 of 89) | 21 % (11 of 53) | 33 % (12 of 36) | 0.33a |

| Unchanged | 66 % (59) | 72 % (38) | 58 % (21) | |

| Decreased | 8 % (7) | 8 % (4) | 8 % (3) | |

*Mantel-Haenszel test of trend

Contributor Information

Mara A. Schonberg, Phone: 617-754-1414, Email: mschonbe@bidmc.harvard.edu.

Valerie Fein-Zachary, Phone: 617-667-3102, Email: vfeinzac@bidmc.harvard.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gotzsche PC, Jorgensen KJ. Screening for breast cancer with mammography. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;6 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001877.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marmot MG, Altman DG, Cameron DA, Dewar JA, Thompson SG, Wilcox M. The benefits and harms of breast cancer screening: an independent review. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:2205–2240. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson HD, Zakher B, Cantor A, Fu R, Griffin J, O’Meara ES, Buist DS, Kerlikowske K, van Ravesteyn NT, Trentham-Dietz A, Mandelblatt JS, Miglioretti DL. Risk factors for breast cancer for women aged 40 to 49 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:635–648. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-9-201205010-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee SJ, Boscardin WJ, Stijacic-Cenzer I, Conell-Price J, O’Brien S, Walter LC. Time lag to benefit after screening for breast and colorectal cancer: meta-analysis of survival data from the United States, Sweden, United Kingdom, and Denmark. BMJ. 2013;346:e8441. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e8441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schonberg MA, Breslau ES, McCarthy EP. Targeting of mammography screening according to life expectancy in women aged 75 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:388–395. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schonberg MA, Leveille SG, Marcantonio ER. Preventive health care among older women: missed opportunities and poor targeting. Am J Med. 2008;121:974–981. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schonberg MA, Silliman RA, Marcantonio ER. Weighing the benefits and burdens of mammography screening among women age 80 years or older. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1774–1780. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.9877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Welch HG, Fisher ES. Diagnostic testing following screening mammography in the elderly. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1389–1392. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.18.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brett J, Bankhead C, Henderson B, Watson E, Austoker J. The psychological impact of mammographic screening: a systematic review. Psycho Oncol. 2005;14:917–938. doi: 10.1002/pon.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heckman BD, Fisher EB, Monsees B, Merbaum M, Ristvedt S, Bishop C. Coping and anxiety in women recalled for additional diagnostic procedures following an abnormal screening mammogram. Health Psychol. 2004;23:42–48. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liao MN, Chen MF, Chen SC, Chen PL. Healthcare and support needs of women with suspected breast cancer. J Adv Nurs. 2007;60:289–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindfors KK, O’Connor J, Acredolo CR, Liston SE. Short-interval follow-up mammography versus immediate core biopsy of benign breast lesions: assessment of patient stress. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:55–58. doi: 10.2214/ajr.171.1.9648763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Novy DM, Price M, Huynh PT, Schuetz A. Percutaneous core biopsy of the breast: correlates of anxiety. Acad Radiol. 2001;8:467–472. doi: 10.1016/S1076-6332(03)80617-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poole K. The emergence of the ‘waiting game’: a critical examination of the psychosocial issues in diagnosing breast cancer. J Adv Nurs. 1997;25:273–281. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997025273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(6):705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schonberg MA, Davis RB, McCarthy EP, Marcantonio ER. External validation of an index to predict up to 9-year mortality of community-dwelling adults aged 65 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1444–1451. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03523.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cockburn J, De Luise T, Hurley S, Clover K. Development and validation of the PCQ: a questionnaire to measure the psychological consequences of screening mammography. Soc Sci Med. 1992;34:1129–1134. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90286-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pineault P. Breast cancer screening: women’s experiences of waiting for further testing. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34:847–853. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.847-853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brett J, Austoker J. Women who are recalled for further investigation for breast screening: psychological consequences 3 years after recall and factors affecting re-attendance. J Public Health Med. 2001;23:292–300. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/23.4.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lerman C, Daly M, Sands C, Balshem A, Lustbader E, Heggan T, Goldstein L, James J, Engstrom P. Mammography adherence and psychological distress among women at risk for breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:1074–1080. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.13.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lerman C, Trock B, Rimer BK, Boyce A, Jepson C, Engstrom PF. Psychological and behavioral implications of abnormal mammograms. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:657–661. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-8-657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rehnberg G, Absetz P, Aro AR. Women’s satisfaction with information at breast biopsy in breast cancer screening. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;42:1–8. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(99)00118-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drageset S, Lindstrom TC. Coping with a possible breast cancer diagnosis: demographic factors and social support. J Adv Nurs. 2005;51:217–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steffens RF, Wright HR, Hester MY, Andrykowski MA. Clinical, demographic, and situational factors linked to distress associated with benign breast biopsy. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2011;29:35–50. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2011.534024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: grounded theory-procedures and techniques. Newbury Park: Sage Publication; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crabtree F, Miller WL, editors. Doing qualitative research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen CC, David A, Thompson K, Smith C, Lea S, Fahy T. Coping strategies and psychiatric morbidity in women attending breast assessment clinics. J Psychosom Res. 1996;40:265–270. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(95)00529-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lebel S, Jakubovits G, Rosberger Z, Loiselle C, Seguin C, Cornaz C, Ingram J, August L, Lisbona A. Waiting for a breast biopsy. Psychosocial consequences and coping strategies. J Psychosom Res. 2003;55:437–443. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00512-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nosarti C, Roberts JV, Crayford T, McKenzie K, David AS. Early psychological adjustment in breast cancer patients: a prospective study. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:1123–1130. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00350-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schnur JB, Montgomery GH, Hallquist MN, Goldfarb AB, Silverstein JH, Weltz CR, Kowalski AV, Bovbjerg DH. Anticipatory psychological distress in women scheduled for diagnostic and curative breast cancer surgery. Int J Behav Med. 2008;15:21–28. doi: 10.1007/BF03003070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seckel MM, Birney MH. Social support, stress, and age in women undergoing breast biopsies. Clin Nurs Spec. 1996;10:137–143. doi: 10.1097/00002800-199605000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deane KA, Degner LF. Determining the information needs of women after breast biopsy procedures. AORN J. 1997;65(767–72):75–76. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2092(06)62998-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Montgomery M, McCrone SH. Psychological distress associated with the diagnostic phase for suspected breast cancer: systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66:2372–2390. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olsson P, Armelius K, Nordahl G, Lenner P, Westman G. Women with false positive screening mammograms: how do they cope? J Med Screen. 1999;6:89–93. doi: 10.1136/jms.6.2.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Di Maio M, Perrone F. Quality of life in elderly patients with cancer. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:44. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ganz PA, Guadagnoli E, Landrum MB, Lash TL, Rakowski W, Silliman RA. Breast cancer in older women: quality of life and psychosocial adjustment in the 15 months after diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4027–4033. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sammarco A. Quality of life of breast cancer survivors: a comparative study of age cohorts. Cancer Nurs. 2009;32:347–356. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31819e23b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mandelblatt JS, Edge SB, Meropol NJ, Senie R, Tsangaris T, Grey L, Peterson BM, Jr, Hwang YT, Kerner J, Weeks J. Predictors of long-term outcomes in older breast cancer survivors: perceptions versus patterns of care. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:855–863. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Silliman RA, Dukes KA, Sullivan LM, Kaplan SH. Breast cancer care in older women: sources of information, social support, and emotional health outcomes. Cancer. 1998;83:706–711. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19980815)83:4<706::AID-CNCR11>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mor V, Allen S, Malin M. The psychosocial impact of cancer on older versus younger patients and their families. Cancer. 1994;74:2118–2127. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19941001)74:7+<2118::AID-CNCR2820741720>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ballantyne PJ. Social context and outcomes for the ageing breast cancer patient: considerations for clinical practitioners. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13:11–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.00921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deimling GT, Arendt JA, Kypriotakis G, Bowman KF. Functioning of older, long-term cancer survivors: the role of cancer and comorbidities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(Suppl 2):S289–S292. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Neale AV, Tilley BC, Vernon SW. Marital status, delay in seeking treatment and survival from breast cancer. Soc Sci Med. 1986;23:305–312. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(86)90352-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ong G, Austoker J, Brett J. Breast screening: adverse psychological consequences one month after placing women on early recall because of a diagnostic uncertainty. A multicentre study. J Med Screen. 1997;4:158–168. doi: 10.1177/096914139700400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Degnim AC, Visscher DW, Berman HK, et al. Stratification of breast cancer risk in women with atypia: a Mayo cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(19):2671–2677. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chun J, Pocock B, Joseph KA, El-Tamer M, Klein L, Schnabel F. Breast cancer risk factors in younger and older women. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(1):96–99. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0176-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schonberg MA, Ramanan RA, McCarthy EP, Marcantonio ER. Decision making and counseling around mammography screening for women aged 80 or older. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(9):979–985. doi: 10.1007/BF02743148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tosteson AN, Fryback DG, Hammond CS. Consequences of false-positive screening mammograms. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(6):954–961. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barton MB, Moore S, Polk S, Shtatland E, Elmore JG, Fletcher SW. Increased patient concern after false-positive mammograms: clinician documentation and subsequent ambulatory visits. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:150–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.00329.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]