Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between cardiovascular disease risk and alcohol consumption according to facial flushing after drinking among Korean men.

Methods

The subjects were 1,817 Korean men (non-drinker group, 283 men; drinking-related facial flushing group, 662 men; non-flushing group, 872 men) >30 years who had undergone comprehensive health examinations at the health promotion center of a Chungnam National University Hospital between 2007 and 2009. Alcohol consumption and alcohol-related facial flushing were assessed through a questionnaire. Cardiovascular disease risk was investigated based on the 2008 Framingham Heart Study. With the non-drinker group as reference, logistic regression was used to analyze the relationship between weekly alcohol intake and cardiovascular disease risk within 10 years for the flushing and non-flushing groups, with adjustment for confounding factors such as body mass index, diastolic blood pressure, low density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, and exercise patterns.

Results

Individuals in the non-flushing group with alcohol consumption of ≤4 standard drinks (1 standard drink = 14 g of alcohol) per week had significantly lower moderate or high cardiovascular disease risk than individuals in the nondrinker group (adjusted odds ratio, 0.51; 95% confidence interval, 0.37 to 0.71). However, no significant relationship between the drinking amount and cardiovascular disease risk was observed in the flushing group.

Conclusion

Cardiovascular disease risk is likely lowered by alcohol consumption among non-flushers, and the relationship between the drinking amount and cardiovascular disease risk may differ according to facial flushing after drinking, representing an individual's vulnerability.

Keywords: Alcohol, Flushing, Cardiovascular Diseases, Risk

INTRODUCTION

Deaths caused by cardiovascular disease are gradually increasing worldwide, including in Korea.1) The increase in the elderly population has been suggested as a fundamental cause. Further, the westernized life style attributable to the improved economy in developing countries is also a factor. In other words, cardiovascular disease risk increases with a decrease in physical activity and an increase in obesity risk resulting from the conveniences of life such as changes in dietary habits, and automobile use. Thus, cardiovascular disease is emerging as an increasingly important public health problem.

The underlying diseases that could lead to cardiovascular disease include diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. The major factors causing cardiovascular diseases in adults are those related to lifestyle such as drinking, smoking, lack of exercise, stress, and eating habits.2,3) Among these factors, drinking is popular among the Korean people, and hence, examining its influence on the development of cardiovascular disease may be important in promoting public health.

A small amount of 1 to 2 drinks of alcohol per day is known to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease. Several studies have identified a J- or U-shaped relationship between alcohol consumption and cardiovascular disease risk. Corrao et al.4) reported that individuals who drink ≤20 g of alcohol a day have a significantly lower relative risk (0.8) of coronary heart disease than those who do not drink at all, and even up to 72 g of alcohol a day may have a protective effect on the risk of coronary heart disease. Furthermore, Muntwyler et al.5) also showed that alcohol consumption lowers the risk of cardiovascular disease. On observing individuals in a cohort of the Physicians' Health Study with a history of myocardial infarction for 5 years, they found that consumption of 1 to 4 drinks a month had a 0.85 relative risk of death; 2 to 4 drinks a week, a 0.79 relative risk of death; and 2 to 4 drinks a day, a 0.84 relative risk of death compared to not drinking at all. In that study, 1 cup of liquor or 1 glass of wine was considered as 1 drink (14 g alcohol). These results indicate a protective effect of alcohol consumption on cardiovascular disease as alcohol increases high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol and inhibits blood coagulation and platelet aggregation. In contrast, Shaper and Wannamethee6) reported that the relative risk of death increases to 1.05 when people with myocardial infarction drink > 3 drinks a day compared to 'occasional drinkers' who drink 1 to 2 drinks a month, with 8 to 10 g of alcohol being considered as 1 drink.

With regard to alcohol-related flushing symptoms, for individuals who do not flush after drinking, consuming ≤4 drinks (1 drink = 14 g alcohol) per week has been reported to improve insulin resistance and health, but for individuals who do flush, alcohol consumption in even small amounts, does not reduce the risk of insulin resistance and rather can increase it.7)

Alcohol is metabolized to acetaldehyde by a number of enzymes. Acetaldehyde is known to interfere with the DNA synthesis and repair mechanism and increases the risk of cancer by generating free radicals.8) Mutations in the gene encoding aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2), the most important among ALDH isoenzymes that break down acetaldehyde, result in inactive ALDH2. Alcohol consumption in individuals with this inactive form of ALDH2 could result in symptoms such as facial flushing, headache, tachycardia, sweating, and nausea. Inactive ALDH2 is much more common in Asian races, including Korean individuals, than in Westerners.9)

However, currently, there is no research on whether alcohol-related flushing, which has been suggested to be related to insulin resistance, affects cardiovascular disease risk. Since diabetes occurs in a large proportion of those with cardiovascular disease and many Korean adults have inactive ALDH2, studies regarding alcohol-related flushing are needed. Thus, the present study was performed to investigate whether alcohol-related flushing affects the relationship between alcohol consumption and cardiovascular disease risk in Korean men.

METHODS

1. Subjects

We studied 1,817 men over the age of 30 years (non-drinker group, 283 men; drink-related facial flushing group, 662 men; non-flushing group, 872 men) who received health checkups at the comprehensive health promotion center of a Chungnam National University Hospital located in Daejeon between 2007 and 2009.

2. Data Collection

Through retrospective reviews of the research subjects' medical records, information was obtained on body measurements, blood tests, and self-administered questionnaires conducted on the day of health screening. The waist circumference was measured at 0.1 cm increments between the iliac crests and the lowest rib while the subject was in an erect position, as recommended by the World Health Organization.10) Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing the body weight (kg) by the square of the height (m) using a Quetelet Index. The blood levels of total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting glucose, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and gamma glutamyl transferase (GGT) were investigated by laboratory tests.

Exercise status, smoking history, alcohol consumption, and the presence of alcohol-related flushing were also investigated. Based on 30-minute exercise sessions, individuals were classified by exercise status as follows: no exercise, irregular exercise (1 or 2 times a week), and regular exercise (at least 3 times a week). With regard to smoking history, subjects were classified as individuals without a history of smoking, individuals who quit smoking, and current smokers. With regard to drinking status, drinking frequency per week and alcohol consumption per drinking episode were investigated. Alcohol consumption was identified following the guidelines of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA)11) where 14 g of alcohol was considered as 1 standard drink.

Flushing after drinking was surveyed by response options of 'always,' 'sometimes,' and 'not always.' Subjects who responded with 'always' and 'sometimes' were assigned to the flushing group, and those who responded with 'not always' were assigned to the non-flushing group, based on the study by Yokoyama et al.12) who reported a sensitivity and specificity of 96.1% and 79.0%, respectively, for the identification of inactive ALDH2 when identifying flushing using this method.

Cardiovascular disease risk was evaluated using the Framingham risk score.13) The Framingham risk score predicts the risk for cardiovascular disease events, i.e., coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, and heart failure, of each patient within 10 years. This measure is converted into cardiovascular disease risk (%) within 10 years by considering gender, age, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, smoking, and presence of diabetes. In the present study, cardiovascular disease risk within 10 years was classified into three groups: <10% (low risk); 10% ≤ and <20% (moderate risk); and 20% ≤ (high risk).

3. Statistical Analysis

General characteristics, anthropometric measurements, and blood test results of the facial flushing and non-flushing groups were compared with the non-drinker group. Categorical variables such as smoking status, exercise status, and cardiovascular disease risk classification were compared using the chi-square test. Continuous variables such as age, BMI, waist circumference, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting glucose, AST, ALT, GGT, weekly alcohol consumption, and Framingham risk score were compared using the t-test. Based on the number of drinking days per week and alcohol consumption on a drinking day, alcohol consumption per week for drinkers was classified as ≤ 4 standard drinks; 4< and ≤ 12 standard drinks; and >12 standard drinks. These classifications are relatively easy to use in medical interviews for the Koreans, since 1 bottle of 'soju,' the most popular alcoholic drink among Koreans, contains about 4 standard drinks. With the non-drinker group used as reference, moderate or high cardiovascular disease risk within 10 years was analyzed for the non-flushing and flushing groups according to weekly alcohol consumption using logistic regression analysis after adjusting for confounding variables such as exercise behavior, diastolic blood pressure, BMI, LDL cholesterol, and triglycerides. PASW SPSS ver. 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Statistical significance levels were set at <0.05.

RESULTS

1. General Characteristics of the Research Subjects

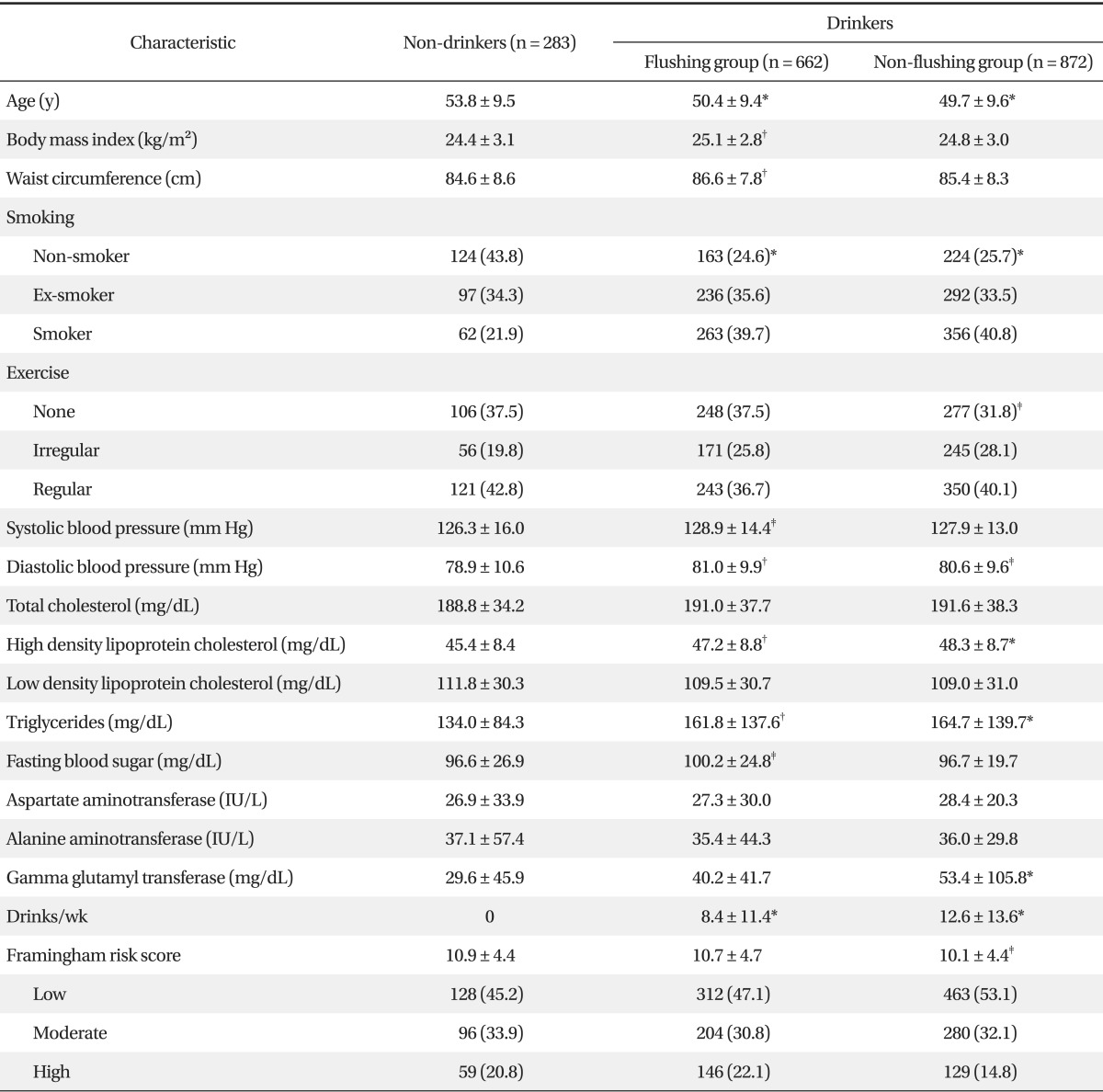

When comparing the general characteristics of the non-flushing and flushing groups with those of the non-drinker group, the mean ± SD age (years) in the flushing group (50.4 ± 9.4) and the non-flushing group (49.7 ± 9.6) was significantly lower than that in the non-drinker group (53.8 ± 9.5). BMI (mean ± SD) in the flushing group (25.1 ± 2.8) was significantly higher than that in the non-drinker group (24.4 ± 3.1). Waist circumference (mean ± SD) in the flushing group was 86.6 ± 7.8 cm, which was significantly higher than that in the non-drinker group (84.6 ± 8.6 cm). With regard to smoking behavior, there were significantly more smokers in the flushing (39.7%) and non-flushing (40.8%) groups than in the non-drinker group (21.9%). With regard to exercise behavior, the non-flushing group had significantly fewer people who did not exercise at all than the non-drinker group.

Systolic blood pressure in the flushing group was significantly higher than that in the non-drinker group. Diastolic blood pressure in both the flushing and non-flushing groups was significantly higher than that in the non-drinker group. The flushing and non-flushing groups showed significantly higher levels of HDL cholesterol and triglycerides than the non-drinker group. The fasting blood glucose level in the flushing group was significantly higher than that in the non-drinker group. GGT in the non-flushing group was significantly higher than that in the non-drinker group. The Framingham risk score of the non-flushing group was 10.1 ± 4.4 points, which was significantly lower than that in the non-drinker group (10.9 ± 4.4 points). Total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, AST, and ALT levels were not significantly different in the flushing and non-flushing groups compared to the non-drinker group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the subjects

Values are presented as mean ± SD or number (%).

*<0.001. †<0.01. ‡<0.05 by the t-test with Bonferroni correction or chi-square test compared with non-drinkers.

2. Difference in the Relationships between Weekly Alcohol Consumption and Moderate or High Cardiovascular Disease Risk According to Facial Flushing

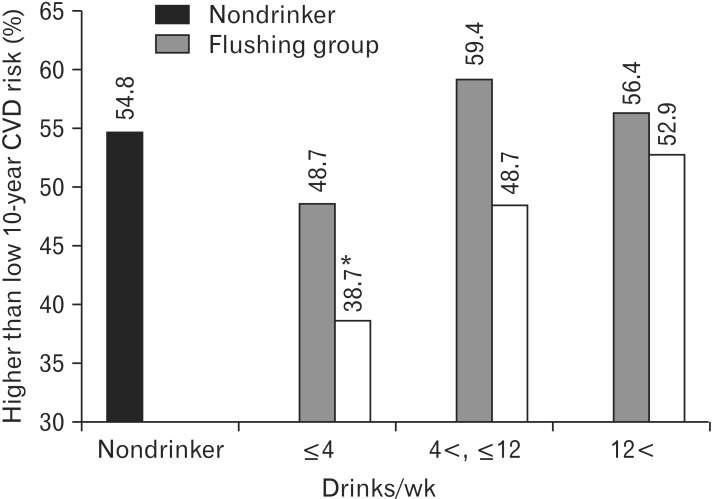

The incidence of moderate or high cardiovascular disease risk (Framingham risk score ≥ 10%) among drinkers was compared with that among non-drinkers, by classifying alcohol consumption as ≤ 4 drinks; 4< and ≤ 12 drinks; and >12 drinks per week. The incidence among non-drinkers was 54.8% and, in the flushing and non-flushing groups, 48.7% and 38.7%, respectively, among those who consumed ≤ 4 drinks; 59.4% and 48.7%, respectively, among those who consumed 4< and ≤ 12 drinks; and 56.4% and 52.9%, respectively, among those who consumed >12 drinks. Individuals in the non-flushing group who consumed ≤ 4 drinks per week had a significantly (P < 0.001) lower incidence of moderate or high cardiovascular disease risk than non-drinkers (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of higher than low 10-year cardiovascular disease risk according to weekly drinking quantity. *P-value < 0.001 by chi-square test comparing with 54.8% of nondrinkers.

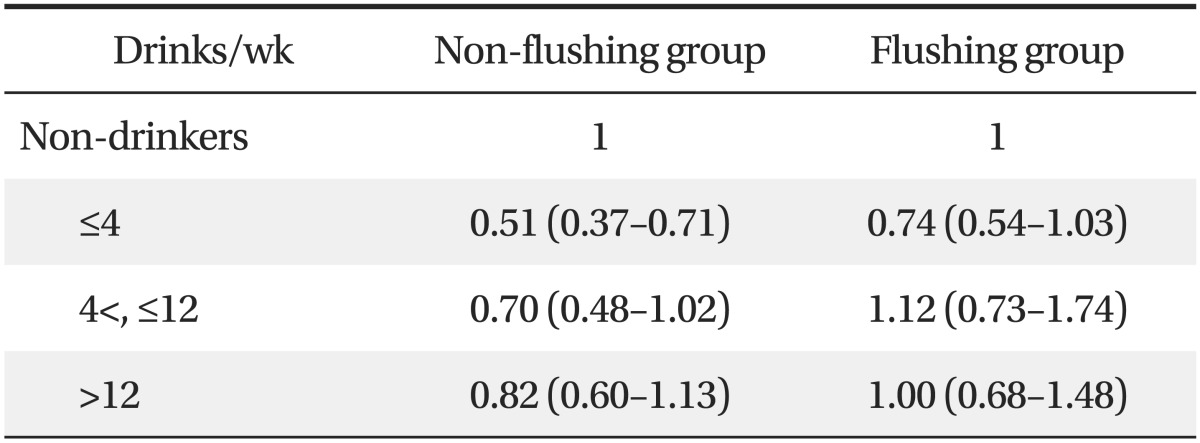

With the non-drinker group used as reference, logistic regression analysis was performed by setting the weekly alcohol consumption of the subjects as the independent variable and the presence of moderate or high cardiovascular disease risk as the dependent variable with adjusting confounding variables being diastolic blood pressure, exercise behavior, BMI, LDL cholesterol, and triglycerides. In the non-flushing group, moderate or high cardiovascular disease risk was significantly decreased (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 0.51; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.37 to 0.71) in those who consumed ≤ 4 drinks per week. However, alcohol consumption did not significantly decrease the moderate or high cardiovascular disease risk in the flushing group for any amount of alcohol consumption (Table 2).

Table 2.

Logistic regression analysis* on higher than low 10-year cardiovascular disease risk† according to weekly drinking quantity in the non-flushing and flushing groups

Values are presented as odds ratio* (95% confidence interval).

*Adjusted for diastolic blood pressure, exercise, body mass index, low density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides. †Defined as 10-year cardiovascular disease risk ≥ 10%.

DISCUSSION

The current study was performed to investigate whether alcohol-related facial flushing affects the relationship between alcohol consumption and cardiovascular disease risk in Korean men. The importance of this study lies in verifying whether the effect of alcohol consumption on moderate or high cardiovascular disease risk within 10 years differs according to individual vulnerability, represented by facial flushing after drinking. In other words, the results of the present study suggest that drinking has a beneficial effect on cardiovascular disease risk in subjects with no facial flushing after drinking, and the subjects who flush after drinking do not experience an alcohol-related reduction in cardiovascular disease risk. These results are thought to have an important meaning in primary care.

In this study, alcohol consumption was related to a significant reduction in moderate or high cardiovascular disease risk in the subjects in the non-flushing group who consumed ≤ 4 drinks per week. These results are consistent with those of Gaziano et al.,14) who found that alcohol consumption of 5 to 6 drinks (1 drink = 14 g alcohol) or less per week can lower the death rate and reduce the mortality caused by cardiovascular disease. Our results also appear to coincide with those of Di Castelnuovo et al.15) in that alcohol consumption of <4 drinks (1 drink = 10 g alcohol) per day in men is associated with a reduction in death rate. The hypothesis that moderate alcohol consumption reduces cardiovascular mortality can be explained as follows: alcohol protects the heart by improving lipid profiles and reducing blood clotting. Suh et al.16) and Djousse et al.17) indicated improved lipid profiles and insulin resistance as the mediating factors in the drinking-related decrease in the mortality caused by cardiovascular disease in women. Arriola et al.18) reported that blood pressure, cholesterol, and diabetes do not affect the relationship between alcohol consumption and the reduction in cardiovascular mortality. Femia et al.19) also reported that these factors are irrelevant for the mortality caused by atherosclerosis and heart disease. Therefore, more studies on the potential mechanism underlying alcohol intake-related decrease in the mortality caused by cardiovascular disease will be needed.

Among the confounding variables adjusted for in this study, LDL cholesterol and triglycerides may affect the total cholesterol and HDL cholesterol levels; hence, we conducted additional analysis with adjustment for exercise behavior, diastolic blood pressure, and BMI without these two variables. The additional analysis showed that the moderate or high cardiovascular disease risk was also significantly decreased (adjusted OR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.49 to 0.92) for individuals in the non-flushing group who consumed 4< and ≤12 drinks per week (data not presented). It is not easy to interpret the results that vary according to the inclusion of LDL cholesterol and triglycerides as confounding variables that were adjusted for. We believe that LDL cholesterol and triglycerides may affect total cholesterol and HDL and may act as independent elements.

For the group with facial flushing after drinking, we were not able to identify an alcohol consumption range associated with reduced cardiovascular disease risk in both the analyses that did and did not include LDL cholesterol and triglycerides in addition to diastolic blood pressure, exercise behavior, and BMI as confounding variables. These results appear to indicate that the impact of alcohol consumption on cardiovascular disease risk can differ according to the presence of facial flushing, because this represents a difference in alcohol metabolism even for the same amount of alcohol consumed. The facial flushing group is thought to show low activity of ALDH2, which decomposes acetaldehyde, compared to the non-flushing group, resulting in acetaldehyde remaining in the body for a long time and potentially acting as a toxin. However, the mechanism by which alcohol adversely affects the cardiovascular system in individuals who show facial flushing as not been studied yet, and therefore, additional studies are required.

In the present study, alcohol consumption appeared to lower the cardiovascular disease risk in the non-flushing group. However, Breslow and Graubard20) reported that consumption of higher amounts of alcohol per drinking episode increases the cardiovascular disease mortality rate. The risk of death from cardiovascular disease with >5 drinks a day (1 drink = 14 g alcohol) was 1.30 compared to 1 drink a day in a cohort study of 20,765 drinkers >18 years of age by the National Health Interview Survey in the United States. Thus the relationship between alcohol consumption and cardiovascular disease risk may depend on the quantity of alcohol consumed, suggesting that alcohol consumption is beneficial in small amounts but harmful in large amounts. Additionally, Breslow and Graubard20) suggested that relatively regular drinking can be beneficial for the risk of cardiovascular disease, reporting that relatively regular and frequent drinkers (range, 120 to 365 drinking days a year) have a 0.79 relative risk of death from cardiovascular disease compared to the most irregular drinkers (range, 1 to 36 drinking days a year). However, despite the possibility of total alcohol consumption in regular and frequent drinkers being higher than that in the most irregular drinkers, Breslow and Graubard20) did not report the total alcohol consumption of the regular, frequent drinkers and the most irregular drinkers, and so it is difficult to verify this.

The result of the current study that the relationship between cardiovascular disease risk and weekly alcohol consumption differs according to the presence of facial flushing is consistent with previous domestic research results that the relationship between weekly alcohol consumption and the risk of metabolic syndrome or hyperhomocysteinemia differs according to the presence of facial flushing. Kim et al.21) reported that the effect of alcohol consumption differed according to the presence of facial flushing, with that the risk of hyperhomocyteinemia decreasing in subjects who consumed ≤8 drinks (1 drink = 14 g alcohol) weekly in the group with no flushing and ≤4 drinks weekly in the group with flushing among 948 health examinees. However, the blood level of homocysteine was not measured in our study, so it is difficult to perform a direct comparison. In another study, Kim et al.22) divided 1,201 health examinees into moderate drinkers (≤14 drinks per week, 1 drink = 14 g alcohol) and heavy drinkers (>14 drinks per week). They reported that the relationship between alcohol consumption and metabolic syndrome differed according to the presence of facial flushing. The group with no facial flushing had a high risk for metabolic syndrome only with heavy drinking, but the group with flushing had a high risk for metabolic syndrome even with moderate drinking. However, while Kim et al.22) classified alcohol consumption as moderate drinking and heavy drinking, the study method in this study was different, with the guideline presented by NIAAA. Alcohol consumption in the present study was further subdivided to identify the threshold of moderate alcohol consumption for Korean subjects. When interpreting the results, the overlap in the research subjects between the study by Kim et al.22) and our study should be considered.

The limitations of this study are as follows. First, the cardiovascular disease risk of Korean men was evaluated using the Framingham risk score, which is targeted for Westerners. In the future, a more appropriate assessment tool needs to be developed to reflect the reality of the Asian population. Second, only men were targeted in the current study. The drinking behaviors of women have changed because of changes in their social life, and the Framingham risk score for women differs from that for men. Further research will be needed to target women. Furthermore, a causal relationship cannot be established with certainty because of the cross-sectional study design, and this will have to be investigated further through a cohort study.

In conclusion, the present study suggests that drinking does not reduce the cardiovascular disease risk for men with facial flushing, while alcohol consumption of ≤4 drinks (56 g alcohol) per week is associated with a significant reduction in cardiovascular disease risk for Korean men with no alcohol-related facial flushing. In addition, the current study suggests that the presence of alcohol-related facial flushing must be considered together with alcohol consumption during health promotion consultation for drinkers.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Statistics Korea. Cause of death statistics 2009 [Internet] Daejeon: Statistics Korea; 2010. [cited 2014 Mar 12]. Available from: http://kostat.go.kr/portal/korea/kor_nw/2/6/1/index.board?bmode=read&aSeq=179505. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinstock RS, Dai H, Wadden TA. Diet and exercise in the treatment of obesity: effects of 3 interventions on insulin resistance. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:2477–2483. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.22.2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lim YT, Park YW, Kim CH, Shin HC, Kim JW. Effect of weight loss on health related quality of life in obese patients. J Korean Acad Fam Med. 2001;22:556–564. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corrao G, Rubbiati L, Bagnardi V, Zambon A, Poikolainen K. Alcohol and coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis. Addiction. 2000;95:1505–1523. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.951015056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muntwyler J, Hennekens CH, Buring JE, Gaziano JM. Mortality and light to moderate alcohol consumption after myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1998;352:1882–1885. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)06351-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaper AG, Wannamethee SG. Alcohol intake and mortality in middle aged men with diagnosed coronary heart disease. Heart. 2000;83:394–399. doi: 10.1136/heart.83.4.394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jung JG, Kim JS, Oh MK. The role of the flushing response in the relationship between alcohol consumption and insulin resistance. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:1699–1704. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poschl G, Seitz HK. Alcohol and cancer. Alcohol Alcohol. 2004;39:155–165. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo R, Ren J. Alcohol and acetaldehyde in public health: from marvel to menace. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010;7:1285–1301. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7041285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry: technical report series 854. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Helping patients who drink too much: a clinician's guide updated 2005 edition [Internet] Bethesda: National Institutes of Health Publication; 2005. [cited 2014 Mar 13]. Available from: http://www.integration.samhsa.gov/clinical-practice/Helping_Patients_Who_Drink_Too_Much.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yokoyama T, Yokoyama A, Kato H, Tsujinaka T, Muto M, Omori T, et al. Alcohol flushing, alcohol and aldehyde dehydrogenase genotypes, and risk for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in Japanese men. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12(11 Pt 1):1227–1233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D'Agostino RB, Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, Wolf PA, Cobain M, Massaro JM, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117:743–753. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaziano JM, Gaziano TA, Glynn RJ, Sesso HD, Ajani UA, Stampfer MJ, et al. Light-to-moderate alcohol consumption and mortality in the Physicians' Health Study enrollment cohort. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:96–105. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00531-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Castelnuovo A, Costanzo S, Bagnardi V, Donati MB, Iacoviello L, de Gaetano G. Alcohol dosing and total mortality in men and women: an updated meta-analysis of 34 prospective studies. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2437–2445. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.22.2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suh I, Shaten BJ, Cutler JA, Kuller LH The Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial Research Group. Alcohol use and mortality from coronary heart disease: the role of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:881–887. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-116-11-881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Djousse L, Lee IM, Buring JE, Gaziano JM. Alcohol consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease and death in women: potential mediating mechanisms. Circulation. 2009;120:237–244. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.832360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arriola L, Martinez-Camblor P, Larranaga N, Basterretxea M, Amiano P, Moreno-Iribas C, et al. Alcohol intake and the risk of coronary heart disease in the Spanish EPIC cohort study. Heart. 2010;96:124–130. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2009.173419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Femia R, Natali A, L'Abbate A, Ferrannini E. Coronary atherosclerosis and alcohol consumption: angiographic and mortality data. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:1607–1612. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000222929.99098.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Breslow RA, Graubard BI. Prospective study of alcohol consumption in the United States: quantity, frequency, and cause-specific mortality. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:513–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim EC, Kim JS, Jung JG, Kim SS, Yoon SJ, Ryu JS. Effect of alcohol consumption on risk of hyperhomocysteinemia based on alcohol-related facial flushing response. Korean J Fam Med. 2013;34:250–257. doi: 10.4082/kjfm.2013.34.4.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim MY, Kim SS, Kim JS, Jung JG, Kwon BR, Ryou YI. Relationship between alcohol consumption and metabolic syndrome according to facial flushing in Korean males. Korean J Fam Med. 2012;33:211–218. doi: 10.4082/kjfm.2012.33.4.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]