Abstract

Depression is one of the most frequent causes of disability in the 21st century. Despite the many preclinical and clinical studies that have addressed this brain disorder, the pathophysiology of depression is not well understood and the available antidepressant drugs are therapeutically inadequate in many patients. In recent years, the potential role of lipid-derived molecules, particularly endocannabinoids (eCBs) and endovanilloids, has been highlighted in the pathogenesis of depression and in the action of antidepressants. There are many indications that the eCB/endovanilloid system is involved in the pathogenesis of depression, including the localization of receptors, modulation of monoaminergic transmission, inhibition of the stress axis and promotion of neuroplasticity in the brain. Preclinical pharmacological and genetic studies of eCBs in depression also suggest that facilitating the eCB system exerts antidepressant-like behavioral responses in rodents. In this article, we review the current knowledge of the role of the eCB/endovanilloid system in depression, as well as the effects of its ligands, models of depression and antidepressant drugs in preclinical and clinical settings.

Keywords: Animal model of depression, antidepressant drug, depression, endocannabinoid system, endovanilloid.

INTRODUCTION

Depression is one of the most common mental disorders in the general population and is projected to become the second leading contributor to the global burden of disease by 2020 [1]. This disorder affects all aspects of human life and is characterized by feelings of sadness, loss of interest or pleasure, guilt, loneliness, low self-worth, disturbed sleep or appetite, low energy level, and poor concentration [2].

Multiple potential mechanisms have been indicated in the etiology of depression. The first theory achieved broad popularity in the mid-1960s and associated depression with reduced brain monoamine levels [3]. The monoamine hypothesis of depression was associated with the therapeutic effect of antidepressant drugs and has dominated our understanding of the pathophysiology of depression for the last decades. However, it is now known that etiology of this mental disorder is much more complex. The role of several agents (i.e., stress, infections and genes) in depression have been well examined, but the psychopharmacology of antidepressant drugs is poorly known and the causes of depression have not been completely explained [4].

A few years ago, the first preclinical reports showing antidepressant-like actions of substances that change the activity of lipid-derived molecules, such as endocannabinoids (eCBs) and endovanilloids, generated a new hypothesis concerning the etiology of depression and novel brain targets for new antidepressant drugs [5]. This idea about the engagement of the eCB system in affective disorders derived from observations of marijuana smokers and the drug’s effects on mood improvement [6-8]. Δ9-THC, which is the principle active cannabinoid in cannabis, mediates most of the drug’s psychoactive and mood-related effects [9]. Although high-dose cannabis use predicts the escalation of risks for anxiety disorders, depression, psychosis and cognitive impairment, especially among teenagers [10-12], a notably high prevalence of comorbid cannabis use occurs in depressed patients (30–64%) as a form of self-medication [7]. This continued use of cannabis in an attempt to control depressive symptoms suggests possible therapeutic benefits in depression [6, 13].

The present review will summarize the current knowledge of the roles of the eCB system and the endovanilloid system in depression and the mechanism of action of antidepressant drugs and will discuss new directions in studies of depression based on a more comprehensive understanding of the eCB system with its cellular signaling targets that participate in this brain disorder.

THE eCB SYSTEM AND DEPRESSION

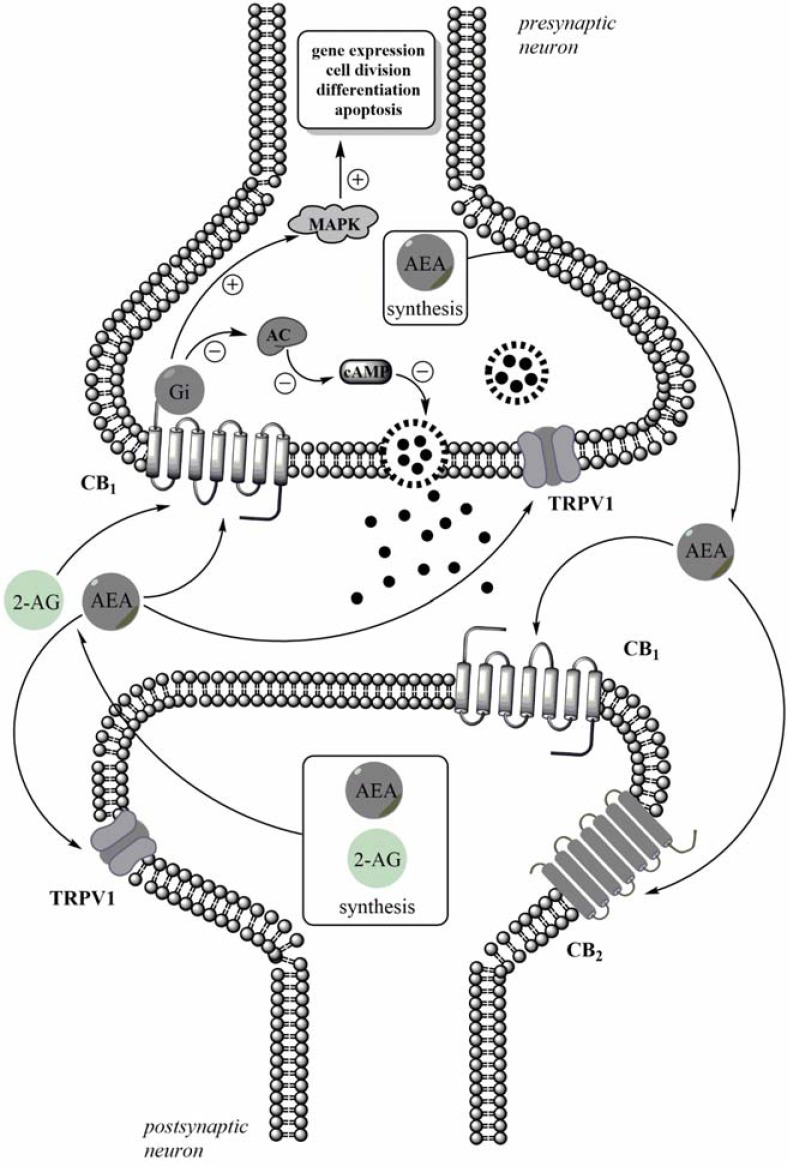

The eCB system consists of eCBs, enzymes responsible for the synthesis and degradation of endogenous ligands and G-coupled CB receptors (CB1 and CB2). eCBs are the arachidonic acid derivatives formed by the hydrolysis of membrane phospholipids. The most defined eCBs is N-arachidonylethanolamide (anandamide, AEA), which is also classified as N-acylethanolamine [14], endovanilloid [15], and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) [16]. Unlike other neurotransmitters, AEA and 2-AG are not stored in secretory vesicles, but are synthesized “on demand” in the postsynaptic neuron through activity-dependent cleavage of membrane lipid precursors and then activate CB receptors as retrograde messengers [17]. AEA is formed presynaptically and travels across the synaptic cleft to activate postsynaptic receptors [18]. AEA is removed from the extracellular space through cellular reuptake and enzymatic degradation. Fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) terminates the biological activity of AEA by hydrolyzing it to arachidonic acid and ethanolamine, while 2-AG can be metabolized by either FAAH in the postsynaptic neurons or by monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL) in pre-synaptic neurons (for review, see [17]). The enzymes involved in eCB catabolism may be important targets for pharmaceutical development. CB1 and CB2 are the primary cannabinoid receptors of the eCB system. CB receptors are metabotropic receptors that are made up of an extracellular, ligand-binding, transmembrane part of the heptahelicase and an intracellular part that activates the Gi protein [19]. Following CB receptor stimulation, G protein activation, inhibition of adenylate cyclase and reduction in cAMP concentrations are observed inside the cell. At the same time, the mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway is stimulated, causing changes in gene expression, cell division, differentiation and apoptosis in cells Fig. (1).

Fig. (1).

Schematic illustration of the eCBs action on CB receptors. 2-AG is synthetized in the postsynaptic dendritic compartment, whereas AEA synthesis may occur post- and pre-synaptically. eCBs are released into extracellular and act as retrograde messengers. Activation of CB1 receptors are associated with Gi-dependent inhibition of adenylyl cyclase (AC) activity, which evoked a decrease of the production of cAMP and resulted in modulation of neurotransmitter release. Via the G-protein, activation of the CB1 receptor activates MAPK pathway, affecting intracellular gene expression, cell division, differentiation and apoptosis.

eCBs and Depression

Animal Research

At the preclinical level, a deficiency in eCB signaling is linked to a "depressive-like" phenotype. In fact, following exposures to several stressors (i.e., chronic unpredictable stress (CUS) and social defeat stress), reduced AEA levels have been noted in the rat hippocampus, hypothalamus, ventral striatum and prefrontal cortex [20], and in the hippocampus and hypothalamus of mice [21]. These data parallel observations in the striatum of olfactory-bulbectomized rats [22] and in the hippocampus of Wistar-Kyoto rats [23], when AEA tissue concentrations were decreased. These findings conflict with recent data in adult rats after a maternal deprivation procedure, in which the levels of AEA increased in some brain areas, such as the nucleus accumbens, caudate-putamen nucleus and mesencephalon [24] (Table 1). The reasons for these differences are unknown, however, several factors such as the ages of the animals and nervous system development, should be taken into account when comparing the levels of AEA.

Table 1.

Changes within the eCB system in animal models of depression.

| Animal Model of Depression | Animal | eCB System Change | References | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eCBs Levels | Degradative Enzymes | Receptors Density | ||||

| AEA | 2-AG | |||||

| Chronic Mild Stress | rat | midbrain- - thalamus- - striatum- - hippocampus- - prefrontal cortex- - | midbrain- - thalamus- ↑ striatum- - hippocampus- - prefrontal cortex- - | FAAH: midbrain- - striatum- - hippocampus- - | midbrain- ↓ hippocampus- - prefrontal cortex- ↑ | [25] |

| rat | No data. | No data. | FAAH: dorsal hippocampus- ↑ (male and female rats) | dorsal and ventral hippocampus- ↓ CB1 in male rats dorsal hippocampus- ↑ CB1 in female rats | [36] | |

| mice | No data. | No data. | No data. | hippocampus- ↓ CB2 | [102] | |

| Chronic Unpredictable Stress | rat | hippocampus- - limbic forebrain- - | hippocampus- ↓ limbic forebrain- - | No data. | hippocampus- ↓ CB1 limbic forebrain- - | [65] |

| rat | prefrontal cortex- ↓ hippocampus- ↓ hypothalamus- ↓ amygdala- ↓ midbrain- ↓ ventral striatum- ↓ | prefrontal cortex- - hippocampus- - hypothalamus- ↑ amygdala- - midbrain- ↑ ventral striatum- - | FAAH: prefrontal cortex- - hippocampus- - hypothalamus- - amygdala- - midbrain- - ventral striatum- - | prefrontal cortex- ↑ CB1 hippocampus- ↓ CB1 hypothalamus- ↓ CB1 amygdala- - midbrain- - ventral striatum- ↓ CB1 | [20] | |

| rat | No data. | No data. | No data. | ventromedial prefrontal cortex- ↑ CB1 dorsomedial prefrontal cortex- - | [71] | |

| Social Defeat Stress | mice | frontal cortex- - hippocampus- ↓ hypothalamus- ↓ striatum- - (acute and repeated social stress) | frontal cortex- ↑ hippocampus- ↑ hypothalamus- ↑ striatum- - (repeatedsocialstress) | No data. | No data. | [21] |

| Maternal Deprivation | rat | hippocampus- - | hippocampus- ↑ (male rats) | No data. | No data. | [26] |

| rat | No data. | No data. | No data. | hippocampus- ↓ CB1- CA1, CA3 ↑ CB2- dentate gyrus, CA1, CA3 | [70] | |

| rat | No data. | No data. | No data. | frontal cortex- ↓ CB1 hippocampus- ↓ CB1 | [66] | |

| rat | No data. | No data. | No data. | CB1: frontal cortex- ↓ CB1 ventral striatum- ↑ CB1 hippocampus- - CB2: frontal cortex- - ventral striatum- - hippocampus- - | [67] | |

| rat | No data. | No data. | No data. | hippocampus- ↓ CB1 | [69] | |

| Maternal Deprivation | rat | nucleus accumbens- ↑ (adolescent and adult) caudate–putamen nucleus- ↑ (adolescent and adult) mesencephalon- ↑ (adolescent) | nucleus accumbens- ↑ (adult) caudate–putamen nucleus- ↑ (adult) mesencephalon- - | No data. | No data. | [24] |

| rat | No data. | No data. | No data. | frontal cortex- ↓ CB1 hippocampus- ↓ CB1 frontal cortex- ↑ CB2 hippocampus- - (male and female rats) | [68] | |

| Olfactory Bulbectomy | rat | No data. | No data. | No data. | prefrontal cortex- ↑ CB1 caudate putamen- - hippocampus- - amygdala- ↑ CB1 dorsal raphe nucleus- - | [72] |

| rat | ventral striatum- ↓ cerebellum- - piriform cortex- - hippocampus- - amygdala- - | ventral striatum- ↓ cerebellum- - piriform cortex- - hippocampus- - amygdala- - | No data. | basal ganglia- - cerebral cortex- -hippocampus- - amygdala- - diencephalon- - brain stem- - | [22] | |

| Wistar-Kyoto Rats | rat | frontal cortex- - hippocampus- ↓ | No data. | FAAH: frontal cortex- ↑ hippocampus- ↑ | frontal cortex- - hippocampus- ↑ CB1 | [23] |

Animal models of depression and stress procedures alter rodent 2-AG brain tissue concentrations. Thus, the 2-AG either decreased in the ventral striatum of olfactory-bulbectomized rats [22] or increased in the thalamus after a chronic mild stress (CMS) procedure [25], in the hypothalamus and midbrain after a CUS procedure [20], in the frontal cortex, hippocampus and hypothalamus after repeated social stress [21], or in the hippocampus and nucleus accumbens after maternal deprivation [24, 26] (Table 1). On the whole, the evidence from preclinical modelsof dysfunction in the eCB levelsis dependent on brain-region and the research tools (the procedures used to generate “depressed” animals).

Reduced AEA levels in rodent models of depression parallel behavioral studies, in which the facilitation of eCB signaling by the AEA uptake inhibitor AM404 [5, 27-29] orAEAalone evoked antidepressant-like activity, which was observed as a reduction of the immobility time in the forced swim test (FST) in animals [28].

Based on the assumption that the eCB system is dampened during depression, antidepressant drugs should alter (reverse) the reduced levels of the eCBs, however, the published evidence is equivocal. A three-week treatment with desipramine, which inhibits the reuptake of noradrenaline (NA) and to a minor extent serotonin (5-HT), did not alter eCB levels [30]. Additionally, the selective 5-HT reuptake inhibitor, fluoxetine, given chronically, does not change the level of eCBs, whereas the monoamine oxidase inhibitor, tranylcypromine, decreases AEA levels in limbic areas and increases 2-AG in the prefrontal cortex [31]. The NA and 5-HT reuptake inhibitor, imipramine, administered chronically (14 days),increases the level of eCBs in the dorsal striatum [32]. Furthermore, unpublished data from our laboratory reveals that 14 days of escitalopram treatment (a selective 5-HT reuptake inhibitor) either increased eCB levels in the hippocampus and dorsal striatum or decreased them in the cortical structures and cerebellum. Finally, chronically administered tianeptine (14 days), a selective 5-HT reuptake enhancer, provoked an increase of the eCB levels in the hippocampus (AEA), dorsal striatum (AEA and 2-AG) and frontal cortex (2-AG) [32] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Modulation of the eCB system by antidepressants.

| Drug (Dose, Treatment, Route) | Animal/ Animal Model of Depression | eCB CHANGE | References | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eCBs Levels | Degradative Enzymes | Receptors Density | ||||

| AEA | 2-AG | |||||

| Desipramine (10 mg/kg); chronic (21 days), i.p. | rat | prefrontal cortex- - hippocampus- - hypothalamus- - amygdala- - | prefrontal cortex- - hippocampus- - hypothalamus- - amygdala- - | No data. | prefrontal cortex- - hippocampus- ↑ CB1 hypothalamus- ↑ CB1 amygdala- - | [30] |

| Imipramine (20 mg/kg), chronic (35 days), i.p. | rat; chronic mild stress | midbrain- - thalamus- - striatum- - hippocampus- - prefrontal cortex- - | No data. | No data. | No data. | [25] |

| Imipramine (10 mg/kg); chronic (21 days); i.p. | rat; chronic unpredictable stress | Reduction not reversed. | Rise not reversed. | prefrontal cortex- - hippocampus- - hypothalamus- - amygdala- - midbrain- ↑ FAAH ventral striatum- ↑ FAAH | Reduction in the hippocampus fully reversed. | [20] |

| Imipramine (15 mg/kg); single; i.p. | rat | prefrontal cortex- - frontal cortex- - hippocampus- ↑ dorsal striatum- - nucleus accumbens- - cerebellum- - | prefrontal cortex- - frontal cortex- ↑ hippocampus- - dorsal striatum- - nucleus accumbens- - cerebellum- ↓ | No data. | No data. | [32] |

| Imipramine (15 mg/kg); chronic (14 days); i.p. | rat | prefrontal cortex- - frontal cortex- - hippocampus- ↑ dorsal striatum- ↑ nucleus accumbens- - cerebellum- - | prefrontal cortex- - frontal cortex- ↑ hippocampus- - dorsal striatum- ↑ nucleus accumbens- - cerebellum- ↓ | No data. | No data. | [32] |

| Tranylcypromine (10 mg/kg); chronic (21 days), i.p. | rat | prefrontal cortex- ↓ hippocampus- ↓ hypothalamus- ↓ | prefrontal cortex- ↑ hippocampus- - hypothalamus- - | No data. | prefrontal cortex- ↑ CB1 hippocampus- ↑ CB1 hypothalamus- - | [31] |

| Fluoxetine (5 mg/kg); chronic (21 days), i.p. | rat | prefrontal cortex- - hippocampus- - hypothalamus- - | prefrontal cortex- - hippocampus- - hypothalamus- - | No data. | prefrontal cortex- ↑ CB1 hippocampus- - hypothalamus- - | [31]{Hill, 2008, Differential effects of the antidepressants tranylcypromine and fluoxetine on limbic cannabinoid receptor binding and endocannabinoid contents} |

| Fluoxetine (10 mg/kg); chronic (14 days), s.c. | rat; olfactory bulbectomy | No data. | No data. | No data. | Rise in the prefrontal cortex fully reversed. | [72] |

| Fluoxetine (10 mg/kg); chronic (14 days), s.c. | rat | No data. | No data. | No data. | prefrontal cortex- - cerebellum- - (- ↑ CB1 receptor inhibition of adenylyl cyclase- prefrontal cortex; - ↓ CB1 receptor inhibition of adenylyl cyclase- cerebellum) without altering receptor density | [86] |

| Citalopram (10 mg/kg); chronic (14 days), s.c. | rat | No data. | No data. | No data. | hypothalamus- ↓ CB1 hippocampus- ↓ CB1 medial geniculate nucleus- ↓ CB1 | [87] |

| Escitalopram (10 mg/kg); single, i.p. | rat | prefrontal cortex- - frontal cortex- - hippocampus- - dorsal striatum- - nucleus accumbens- - cerebellum- - | prefrontal cortex- - frontal cortex- ↓ hippocampus- - dorsal striatum- - nucleus accumbens- - cerebellum- - | No data. | No data. | [32] |

| Escitalopram (10 mg/kg); chronic (14 days), i.p. | rat | prefrontal cortex- - frontal cortex- - hippocampus- ↑ dorsal striatum- ↑ nucleus accumbens- - cerebellum- - | prefrontal cortex- ↓ frontal cortex- ↓ hippocampus- ↑ dorsal striatum- ↑ nucleus accumbens- - cerebellum- ↓ | No data. | No data. | [32] |

| Tianeptine (10 mg/kg); single, i.p. | rat | prefrontal cortex- - frontal cortex- - hippocampus- - dorsal striatum- - nucleus accumbens- - cerebellum- - | prefrontal cortex- - frontal cortex- - hippocampus- - dorsal striatum- - nucleus accumbens- - cerebellum- - | No data. | No data. | [32] |

| Tianeptine (10 mg/kg); chronic (14 days), i.p. | rat | prefrontal cortex- - frontal cortex- - hippocampus- ↑ dorsal striatum- ↑ nucleus accumbens- - cerebellum- - | prefrontal cortex- - frontal cortex- ↑ hippocampus- - dorsal striatum- ↑ nucleus accumbens- - cerebellum- - | No data. | No data. | [32] |

These data seem to support the participation of eCBs in the mechanism of action of clinically effective and potential antidepressants, however, in rats subjected to experimental stress, imipramine given acutely [25] or chronically [20] did not reverse the changes in eCB levels in rats exposed to CMS or CUS, respectively, in several brain structures (Table 2). Because there have been no studies with other antidepressant drugs, further research is urgently needed to validate the relationship between depression-like phenotypes and eCB levels.

Human Research

In humans, there are several lines of evidence that a dysfunction in the eCB system is implicated in the pathogenesis of depression. In postmortem studies, elevated levels of eCBs have been observed in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of alcoholic suicide victims [33]. The authors proposed that such increases in eCB levels, linked with memories of aversive stimuli, may induce emotional discomfort during depression. In clinical trials of untreated depressed patients, a rise in serum AEA level has been observed [34, 35], while reductions in 2-AG have been observed in human female patients with major depression [34].

eCB Degradative Enzymes

Animal Research

Inpreclinical studies, depression-like behavior seems to be associated with raised brain levels of FAAH (and subsequently reduced local levels of AEA). In animal models of depression, Wistar-Kyoto rats display higher levels of FAAH in the frontal cortex and hippocampus, with unaltered levels of the AEA-synthesizing enzyme N-arachidonyl phosphatidyl ethanolamine specific phospholipase-D (NAPE-PLD) [23], and CMS evokes an up-regulation of FAAH levels in the dorsal hippocampi of both male and female animals [36] (Table 1). These findings are supported by studies in FAAH knockout mice that revealed anxiolytic-like and antidepressant-like effects linked to altered 5-HT transmission and postsynaptic 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A/2C receptor function [37]. These findings revealed a relationship between abnormalities in FAAH function and the depressive phenotype that were not confirmed by Hill et al. [20] and Bortolato et al. [25]. In fact, neither CUS nor CMS affected the maximal hydrolytic activity of FAAH or the binding affinity of AEA for FAAH in several rat brain regions [20] or the FAAH activity in the midbrain, striatum and hippocampus of animals [25]. In enzymes related to 2-AG degradation, a decrease of the membrane-associated MAGL expression has been observed in stressed mice [38]. Enhancing eCB signaling by inhibiting degradative enzymes evokes anti-inflammatory effects. In fact, increased AEA levels reduce the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and inflammatory mediators [39, 40] and enhance the release of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 [41]. Notably, one hypothesis of the pathogenesis of depression is that it is highly connected with increased concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines [42].

Pharmacological manipulations of FAAH activity alter mood and exert antidepressant-like behavioral responses in rodents. Administration of the FAAH inhibitor (URB597 [5, 23, 27, 28, 43-49]) or the MAGL inhibitor (URB602 [50]) to rodents decreases their immobility time in the FST. Further, a 5-week administration of URB597 resulted in inhibited brain FAAH activity accompanied with a reduction in the body weight and sucrose intake induced by CMS in rats [25]. A very recent study demonstrated a reduction in chronic stress-induced depressive-like behaviors by inhibiting the MAGL with JZL184, followed by an enhancement of eCB signaling in the hippocampus that was linked to the mammalian target of rapamicin (mTOR) pathway [51]. These data point to the potential therapeutic application of eCB-strengthening agents indepression.

Little is known about the effects of antidepressants in FAAH activity assays, however, one study showed that imipramine administration resulted in increased activation of FAAH activity in the ventral striatum and midbrain of rats subjected to CUS and that co-treatment of imipramine and CUS robustly activated FAAH function [20] (Table 2).

Human Research

In the latest study by [52], greater FAAH activity was identified in the ventral striatum of alcohol-dependent suicides, compared to alcohol-dependent nonsuicides. This postmortem study seems to indicate increased FAAH activity as a crucial factor for depression and suicide in depressed human patients.

CB Receptors

CB1 Receptors

CB1 receptors contributed to the depressive-like phenotypes in both animal and human studies. These receptors are widely localized in brain structures implicated in the pathogenesis of depression (the prefrontal cortex, frontal cortex, hippocampus, cerebellum) and are linked to anhedonia (the dorsal striatum and nucleus accumbens) [53, 54]. At the functional level, CB1 receptors modulate brain neurotransmission, including the NA, 5-HT, dopamine (DA),

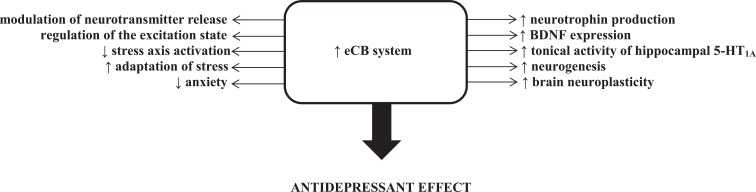

γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glutamate systems, inhibit the stress axis and restore brain neuroplasticity Fig. (2) [55]. The GABAergic interneurons (inhibitory) and glutaminergic (excitatory) neurons represent opposing players regulating the excitation state of the brain. Interestingly, these cell types both highly express CB1 receptors [56], thus, CB receptor-mediated signaling is responsible for maintaining the homeostasis of excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters. Additionally, they are many findings which suggest a functional correlation among eCBs and dopaminergic systems during striatal signaling. In fact, in vivo striatal administration of the D2 dopamine receptor agonist quinpirole induces a local increase in the level of AEA [57] and quinpirole perfusion into striatal slices in vitro evokes the same increase [58]. Additionally, CB1 receptor agonists stimulate DA release in the nucleus accumbens [59].

Fig. (2).

Increased eCB stimulation produced several biochemical changes (modulation of neurotransmitter release, regulation of the excitation state, inhibition of the stress axis, rise of neurotrophin production and promotion of the neurogenesis process), which are implicated in antidepressant effects.

Animal Research

In preclinical studies, genetic deletion of CB1 receptors in mice results in a phenotype that strikingly resembles the profile of severe, typical depression; a similar depression-like behavioral phenotype was found after CB1 receptor blockade [60-64]. These findings correlate well with the lower density of CB1 receptors in animal models of depression induced by stress in rats [20, 25, 36, 65], and such down-regulation of CB1 receptors has been observed in the midbrain, hippocampus, hypothalamus and ventral striatum. In maternal deprivation models, a reduction of the CB1 receptors occurs in the frontal cortex [66-68] and hippocampus [66, 68-70]. Interestingly, thischange in CB1 receptor density was also apparent in the rat prefrontal cortex, where a rise was observed in animal models of depression evoked by stress factors [20, 25, 71] or by lesion of the olfactory bulbs [72] (Table 1).

Facilitation of CB1 receptor signaling exerts antidepressant-like behavioral responses in rodents, but it is worth noting that many side effects, particularly related to psychosomatic activation, will limit the therapeutic use of direct agonists. Nonselective (CB1/CB2) agonists such Δ9-THC [13, 73, 74], CP55,940 [27], WIN55,212-2 [46] and HU-210 [5, 45, 75] given acutely or subchronically decrease immobility time in the FST in rodents, indicating their antidepressant activity. In contrast, long-term exposure to Δ9-THC [76] and WIN55,212-2 [77] during adolescence (but not during adulthood) induces depression-like and anxiety-like behaviors in adulthood in rats, and the extended immobility time after Δ9-THC exposure was also observed in mice [78]. However, based on the bimodal action of eCB ligands on mood, a case could be made for the opposite. The antagonism of CB1 receptors with rimonabant (SR141716) or AM251 produces antidepressant effects in rodents [63, 74, 79-85], but these findings are not useful for translational research as they have not been replicated in human studies (see below).

Based on these observations, in which the eCB system is damped during depression (above), antidepressant drugs should increase brain CB1 receptor levels and/orreverse the reduced levels of the CB1 receptor density associated with depressive phenotypes. In fact, a rise in CB1 receptor expression has been demonstrated following chronic treatment with desipramine in the hypothalamus and hippocampus [30], following tranylcypromine in the the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus and after fluoxetine in the prefrontal cortex [31]. Furthermore, fluoxetine-induced enhancement of the CB1 receptor-dependent inhibition of adenylyl cyclase in the prefrontal cortex did not correlate with receptor density [86], and chronically administered citalopram caused a reduction in the CB1 receptor density in the hypothalamus, hippocampus and medial geniculate nucleus [87] (Table 2).

With animal models of depression, chronic fluoxetine administration reversed the increased CB1-receptor signaling in the prefrontal cortex of bulbectomized rats [72], while imipramine reversed the reduced CB1 receptor density only in the rat hippocampus during exposure to CUS [20] (Table 2).

The eCB system alters the activity of the serotonergic system through CB1 receptors, including transmission and receptor expression [37]. In the CB1 knockout mice, the activity of serotonergic neurons was facilitated in the dorsal raphe nucleus along with altered 5-HT feedback and with increased 5-HT extracellular levels in the prefrontal cortex. In this mouse genotype, fluoxetine failed to facilitate serotonergic neurotransmission in the prefrontal cortex [88], while the antidepressant effect of desipramine was blocked [63]. Recently, microdialysis in the rat prefrontal cortex revealed that CB1 receptors control extracellular 5-HT levels; selective CB1 receptor stimulation reduced the effect of citalopram on local 5-HT levels, while CB1 receptor blockade increased it [89].

These data not only link CB1 receptor functionality with serotonergic antidepressants [63, 86, 90] but strongly support the engagement of CB1 receptors in depression.

Human Research

In human postmortem studies, the CB1 density in cortical areas either decreased in mood disorders [34, 91] or increased in depressed suicide victims [92, 93]. Elevated level of the CB1 receptors have been observed in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex [33] and in the ventral striatum [52] of alcoholic suicide victims; the latter changes were not associated with alcohol dependence, as in alcohol-dependent non-suicides a downregulation of CB1 receptors was noted [52]. To support the involvement of tonic CB1 receptor activation in the pathophysiology of depression, the body of clinical evidence indicates that the dysfunction of the CB1 receptors is a critical factor for the development of depressive symptoms. In clinical trials administration of the CB1 receptor antagonist rimonabant (SR141716A) to humans for the treatment of obesity evoked adverse psychiatric effects [94]. 20 mg/kg/day of the drug caused depressed mood disorders and an increased risk of developing anxiety in the obese people, leading to their exclusion from the rimonabant therapy [94]. Treatment with rimonabant also resulted in suppression of positive affective memories, a decrease of neural responses to rewarding stimuli and the development of anhedonia [95]. In other clinical trials, acute and multiple doses of taranabant, a CB1 receptor inverse agonist,used for the treatment of obesity, caused anxiety and mood changes in healthy male volunteers [96, 97].

CB2 Receptors

Some investigators indicate that CB2 receptors can play a role in depression [98-100]. These receptors are localized in glial cells and neurons in the hippocampus, hypothalamus, amygdala, cerebellum and cerebral cortex [101], which suggests that they may be involved in the regulation of mood disorders [102].

Animal Research

The first study of CB2 receptors in depression uncovered a decreased density of these receptors in the midbrain, striatum and hippocampus in stressed mice [103]. In the CMS model, a reduced CB2 receptor density was reported in the mouse hippocampus [102]. These findings were not confirmed in a maternal deprivation model where the density of CB2 receptors either increased in the rat frontal cortex [68] and hippocampus [70], or did not change in the hippocampus [67, 68] (Table 1). These conflicting changes in CB2 receptor density may be a result of the sensitivity of the different methods used (immunohistochemistry [70] vs. Western blot [67, 68]). Are duction in brain CB2 receptors noted in some models of depression correlates with genetic studies in which CB2 receptor overexpression creates a behavioral endophenotype resistant to depressogenic stimuli [102]. Additionally, CMS evokes a drop in the expression of the BDNF and CB2 receptor genes in the hippocampus of stressed mice, which was reversed by chronic administration of a CB2 antagonist (AM630) [102]. Further, chronic administration of the CB2 receptor agonist JWH015 increased sucrose consumption in control mice in CMS [103], while another agonist,GW405833, decreased the immobility time in FST in rats with neuropathic pain [99]. In contrast to CB2 receptor stimulation, the chronic administration of a CB2 receptor antagonist did not change the sucrose consumption in mice in CMS, but it also reduced the immobility time during FST [102, 103].

Presently, there is no data showing the changes in CB2 receptor density elicited by antidepressant drugs.

Human Research

A high incidence of Q63R polymorphism in the CB2 gene was found in depressed and alcoholic Japanese subjects [103]. In postmortem studies, the CB2 mRNA levels in the prefrontal cortex, in contrast to CB1 levels, did not decrease during postnatal development in humans ranging in age from birth to 50 years, and the CB2 levels in the prefrontal cortex of either major depression or bipolar disorder patients were not significantly different when compared to age-matched controls [92]. Based on this human research, CB2 receptors seem to display secondary/additional targeting during depression, in contrast to the CB1 receptors’ dominant role in depression.

THE ENDOVANILLOID SYSTEM AND DEPRESSION

The endovanilloid system is composed of endogenous vanilloids, synthesizing and catabolic enzymes and receptors (TRPV1). Three different classes of endovanilloids have been recognized, including AEA and its congeners (i.e., the N-acylethanolamines (NAEs)), the N-acyldopamines (N-oleoyl-dopamine and N-arachidonoyl-dopamine (NADA)) and some lipoxygenase derivatives of arachidonic acid (i.e.,12-hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acid (12-HPETE)) [104]. These endovanilloids are synthesized and released in an activity-dependent manner via enzymatic conversion. AEA and NAEs biosynthesis depends on NAPE-PLD activity while 12-lipoxygenase (12-LOX) is required for 12-HPETE formation. The endovanilloids are inactivated rapidly by FAAH (the main degrading enzyme for AEA and NAEs) and cathechol-O-methyl-transferase (COMT) (required for NADA degradation). The endovanilloids activate TRPV1 receptors, nonselective cation channels that may be activated by physical and chemical agents. TRPV1 receptors are widely expressed in various areas of the brain, including the hippocampus (pyramidal neurons of the CA3 region) and cerebellum (Purkinje’s neurons). In line with this information, the co-expression of TRPV1 and CB1 receptors in brain neurons allows for cross-talk between endovanilloids and eCBs [104].

The physiological and pathological roles of the endovanilloid system still have not been fully elucidated, however, pharmacological manipulation of the activity of TRPV1 receptors might be useful to treatpain, anxiety, emesis and locomotor disorders. Despite the demonstrated the roles of TPRV1 receptors in locomotion, emotion and cognitive behaviors, their role in depression is still not established. The localization of the TRPV1 receptors in the brain suggests their role in emotional responses [105]. Stimulation of TPRV1 receptors causes the depolarization of neurons and the release of glutamate, which is implicated in the release of others neurotransmitters (GABA, DA, NA or 5-HT) [15]. Additionally, the endovanilloid ligands with the eCB ligands bi-directionally modulate presynaptic Ca2+ levels and neurotransmitter release [106]. The endovanilloids seem to play a role as autocrine neuromodulators and/or second messengers in the brain.

Animal Research

From the preclinical point of view, the loss of TRPV1 induces “antidepressant, anxiolytic, abnormal social and reduced memorial behaviors” [107]. TRPV1 knockout mice exhibit reduced immobility time the FST and reduced latency times in the novelty-suppressed feeding paradigm, demonstrating a decreased depressive response [107]. An acute, desensitizing dose of selective agonists of TRPV1 (olvanil and capsaicin) reduce the immobility time in mice [108-110] but raises this parameter in rats (olvanil) [111], while selective antagonists of TRPV1 (capsazepine) reduce the immobility in mice [109]. In addition, capsazepine also increases the antidepressant activity of a sub-threshold dose of fluoxetine in the FST in mice [109]. Moreover, a synthetic agonist of CB1 and TRPV1 receptors, arvanil, elicits significant antidepressant-like effects in mice [108]. TRPV1 receptors modulate input to the locus coeruleus, which is implicated in major depression, stress and memory [112].

Human Research

No data.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, the eCB and endovanilloid system, through different effects on cellular processes (levels of neurotransmitters, neurogenesis, the HPA axis) may function as a central player to connect previously known theories of depression and may play a significant role in the pathogenesis of the disease and the mechanism of action of antidepressants, and it may serve as a target for drug design and discovery. It should be emphasized that, according to recent theories of depression, one of the causes of this disease is impaired neurogenesis, and endogenous ligands of the eCB system can reinforce hippocampal neurogenesis by increasing brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression, raising the possibility of a role for the eCB system in antidepressant drug action, and underscoring the role of these fascinating lipid mediators in depression. The endovanilloid ligands as potential brain modifiers could also be novel therapeutic targets for the treatment of depression. However, their role in depression is still poorly understood and future studies are needed to clarify the exact contribution of endovanilloids to the pathogenesis of depression and to the mechanism of action of antidepressant drugs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the research grant UMO-2012/05/B/NZ7/02589 from the National Science Centre, Kraków, Poland and statutory funds from the Jagiellonian University (K/ZDS/001425).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author(s) confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- AEA

= anandamide

- 2-AG

= 2-arachidonoylglycerol

- eCBs

= endocannabinoids

- 12-HPETE

= 12-hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acid

- LC-MS/MS

= liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry

- NAEs

= N-acylethanolamines

- NADA

= N-arachidonoyl-dopamine

REFERENCES

- 1.Pilkington K. Anxiety, depression and acupuncture A review of the clinical research. Auton. Neurosci. 2010;157(1-2):91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nardi B, Francesconi G, Catena-Dell'osso M, Bellantuono C. Adolescent depression: clinical features and therapeutic strategies. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2013;17(11):1546–1551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prins J, Olivier B, Korte SM. Triple reuptake inhibitors for treating subtypes of major depressive disorder the monoamine hypothesis revisited. Expert Opin. Invest. Drugs. 2011;20(8):1107–1130. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2011.594039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Massart R, Mongeau R, Lanfumey L. Beyond the monoaminergic hypothesis neuroplasticity and epigenetic changes in a transgenic mouse model of depression. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2012;367(1601):2485–2494. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill MN, Gorzalka BB. Pharmacological enhancement of cannabinoid CB1 receptor activity elicits an antidepressant-like response in the rat forced swim test. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;15(6):593–599. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bambico FR, Gobbi G. The cannabinoid CB1 receptor and the endocannabinoid anandamide possible antidepressant targets. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 2008;12(11):1347–1366. doi: 10.1517/14728222.12.11.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ashton CH, Moore PB, Gallagher P, Young AH. Cannabinoids in bipolar affective disorder a review and discussion of their therapeutic potential. J. Psychopharmacol. 2005;19(3):293–300. doi: 10.1177/0269881105051541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ware MA, Adams H, Guy GW. The medicinal use of cannabis in the UK: results of a nationwide survey. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2005;59(3):291–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2004.00271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huestis MA, Gorelick DA, Heishman SJ, Preston KL, Nelson RA, Moolchan ET, Frank RA. Blockade of effects of smoked marijuana by the CB1-selective cannabinoid receptor antagonist SR141716. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2001;58(4):322–328. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.4.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Copeland J, Rooke S, Swift W. Changes in cannabis use among young people impact on mental health. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry. 2013;26(4):325–329. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328361eae5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tziraki S. Mental disorders and neuropsychological impairment related to chronic use of cannabis. Rev. Neurol. 2012;54(12):750–760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chadwick B, Miller ML, Hurd YL. Cannabis Use during Adolescent Development Susceptibility to Psychiatric Illness. Front. Psychiatry. 2013;4:129. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bambico FR, Hattan PR, Garant JP, Gobbi G. Effect of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol on behavioral despair and on pre- and postsynaptic serotonergic transmission. Prog. Neuropsycho-pharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2012;38(1):88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Devane WA, Hanus L, Breuer A, Pertwee RG, Stevenson LA, Griffin G, Gibson D, Mandelbaum A, Etinger A, Mechoulam R. Isolation and structure of a brain constituent that binds to the cannabinoid receptor. Science. 1992;258(5090):1946–1949. doi: 10.1126/science.1470919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Starowicz K, Nigam S, Di Marzo V. Biochemistry and pharmacology of endovanilloids. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007;114(1):13–33. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sugiura T, Kondo S, Sukagawa A, Nakane S, Shinoda A, Itoh K, Yamashita A, Waku K. 2-Arachidonoylglycerol a possible endogenous cannabinoid receptor ligand in brain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995;215(1):89–97. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahn K, McKinney MK, Cravatt BF. Enzymatic pathways that regulate endocannabinoid signaling in the nervous system. Chem. Rev. 2008;108(5):1687–1707. doi: 10.1021/cr0782067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castillo PE, Younts TJ, Chavez AE, Hashimotodani Y. Endocannabinoid signaling and synaptic function. Neuron. 2012;76(1):70–81. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howlett AC, Barth F, Bonner TI, Cabral G, Casellas P, Devane WA, Felder CC, Herkenham M, Mackie K, Martin BR, Mechoulam R, Pertwee RG. International Union of Pharmacology.XXVII. Classification of cannabinoid receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 2002;54(2):161–202. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hill MN, Carrier EJ, McLaughlin RJ, Morrish AC, Meier SE, Hillard CJ, Gorzalka BB. Regional alterations in the endocannabinoid system in an animal model of depression effects of concurrent antidepressant treatment. J. Neurochem. 2008;106(6):2322–2336. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05567.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dubreucq S, Matias I, Cardinal P, Haring M, Lutz B, Marsicano G, Chaouloff F. Genetic dissection of the role of cannabinoid type-1 receptors in the emotional consequences of repeated social stress in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(8):1885–1900. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eisenstein SA, Clapper JR, Holmes PV, Piomelli D, Hohmann AG. A role for 2-arachidonoylglycerol and endocannabinoid signaling in the locomotor response to novelty induced by olfactory bulbectomy. Pharmacol Res. 2010;61(5):419–429. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2009.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vinod KY, Xie S, Psychoyos D, Hungund BL, Cooper TB, Tejani-Butt SM. Dysfunction in fatty acid amide hydrolase is associated with depressive-like behavior in Wistar Kyoto rats. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e36743. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naudon L, Piscitelli F, Giros B, Di Marzo V, Dauge V. Possible involvement of endocannabinoids in the increase of morphine consumption in maternally deprived rat. Neuro- pharmacology. 2013;65:193–199. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bortolato M, Mangieri RA, Fu J, Kim JH, Arguello O, Duranti A, Tontini A, Mor M, Tarzia G, Piomelli D. Antidepressant-like activity of the fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibitor URB597 in a rat model of chronic mild stress. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(10):1103–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Llorente R, Llorente-Berzal A, Petrosino S, Marco EM, Guaza C, Prada C, Lopez-Gallardo M, Di Marzo V, Viveros MP. Gender-dependent cellular and biochemical effects of maternal deprivation on the hippocampus of neonatal rats: a possible role for the endocannabinoid system. Dev. Neurobiol. 2008;68(11):1334–1347. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adamczyk P, Golda A, McCreary AC, Filip M, Przegalinski E. Activation of endocannabinoid transmission induces antidepressant-like effects in rats. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2008;59(2):217–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Umathe SN, Manna SS, Jain NS. Involvement of endocannabinoids in antidepressant and anti-compulsive effect of fluoxetine in mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2011;223(1):125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mannucci C, Navarra M, Pieratti A, Russo GA, Caputi AP, Calapai G. Interactions between endocannabinoid and serotonergic systems in mood disorders caused by nicotine withdrawal. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2011;13(4):239–247. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hill MN, Ho WS, Sinopoli KJ, Viau V, Hillard CJ, Gorzalka BB. Involvement of the endocannabinoid system in the ability of long-term tricyclic antidepressant treatment to suppress stress-induced activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31(12):2591–2599. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hill MN, Ho WS, Hillard CJ, Gorzalka BB. Differential effects of the antidepressants tranylcypromine and fluoxetine on limbic cannabinoid receptor binding and endocannabinoid contents. J. Neural Transm. 2008;115(12):1673–1679. doi: 10.1007/s00702-008-0131-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smaga I, Bystrowska B, Gawlinski D, Pomierny B, Stankowicz P, Filip M. Antidepressants and Changes in Concentration of Endocannabinoids and N-Acylethanolamines in Rat Brain Structures. Neurotox. Res. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s12640-014-9465-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vinod KY, Arango V, Xie S, Kassir SA, Mann JJ, Cooper TB, Hungund BL. Elevated levels of endocannabinoids and CB1 receptor-mediated G-protein signaling in the prefrontal cortex of alcoholic suicide victims. Biol. Psychiatry. 2005;57(5):480–486. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hill MN, Miller GE, Ho WS, Gorzalka BB, Hillard CJ. Serum endocannabinoid content is altered in females with depressive disorders a preliminary report. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2008;41(2):48–53. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-993211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ho WS, Hill MN, Miller GE, Gorzalka BB, Hillard CJ. Serum contents of endocannabinoids are correlated with blood pressure in depressed women. Lipids Health Dis. 2012;11:32. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-11-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reich CG, Taylor ME, McCarthy MM. Differential effects of chronic unpredictable stress on hippocampal CB1 receptors in male and female rats. Behav. Brain Res. 2009;203(2):264–269. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bambico FR, Cassano T, Dominguez-Lopez S, Katz N, Walker CD, Piomelli D, Gobbi G. Genetic deletion of fatty acid amide hydrolase alters emotional behavior and serotonergic transmission in the dorsal raphe, prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(10):2083–2100. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sumislawski JJ, Ramikie TS, Patel S. Reversible gating of endocannabinoid plasticity in the amygdala by chronic stress a potential role for monoacylglycerol lipase inhibition in the prevention of stress-induced behavioral adaptation. Neuropsycho-pharmacology. 2011;36(13):2750–2761. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Puffenbarger RA, Boothe AC, Cabral GA. Cannabinoids inhibit LPS-inducible cytokine mRNA expression in rat microglial cells. Glia. 2000;29(1):58–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tham CS, Whitaker J, Luo L, Webb M. Inhibition of microglial fatty acid amide hydrolase modulates LPS stimulated release of inflammatory mediators. FEBS Lett. 2007;581(16):2899–2904. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Correa F, Hernangomez M, Mestre L, Loria F, Spagnolo A, Docagne F, Di Marzo V, Guaza C. Anandamide enhances IL-10 production in activated microglia by targeting CB(2) receptors: roles of ERK1/2, JNK, and NF-kappaB. Glia. 2010;58(2):135–147. doi: 10.1002/glia.20907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dantzer R. Cytokine, sickness behavior, and depression. Immunol. Allergy Clin. North Am. 2009;29(2):247–264. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rutkowska M, Jachimczuk O. Antidepressant--like properties of ACEA (arachidonyl-2-chloroethylamide) the selective agonist of CB1 receptors. Acta Pol. Pharm. 2004;61(2):165–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gobbi G, Bambico FR, Mangieri R, Bortolato M, Campolongo P, Solinas M, Cassano T, Morgese MG, Debonnel G, Duranti A, Tontini A, Tarzia G, Mor M, Trezza V, Goldberg SR, Cuomo V, Piomelli D. Antidepressant-like activity and modulation of brain monoaminergic transmission by blockade of anandamide hydrolysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci U. S. A. 2005;102(51):18620–18625. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509591102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jiang W, Zhang Y, Xiao L, Van Cleemput J, Ji SP, Bai G, Zhang X. Cannabinoids promote embryonic and adult hippocampus neurogenesis and produce anxiolytic- and antidepressant-like effects. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115(11):3104–3116. doi: 10.1172/JCI25509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bambico FR, Katz N, Debonnel G, Gobbi G. Cannabinoids elicit antidepressant-like behavior and activate serotonergic neurons through the medial prefrontal cortex. J. Neurosci. 2007;27(43):11700–11711. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1636-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Realini N, Vigano D, Guidali C, Zamberletti E, Rubino T, Parolaro D. Chronic URB597 treatment at adulthood reverted most depressive-like symptoms induced by adolescent exposure to THC in female rats. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60(2-3):235–243. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Naidu PS, Varvel SA, Ahn K, Cravatt BF, Martin BR, Lichtman AH. Evaluation of fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibition in murine models of emotionality. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;192(1):61–70. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0689-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McLaughlin RJ, Hill MN, Bambico FR, Stuhr KL, Gobbi G, Hillard CJ, Gorzalka BB. Prefrontal cortical anandamide signaling coordinates coping responses to stress through a serotonergic pathway. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;22(9):664–671. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wright LK, Liu J, Nallapaneni A, Pope CN. Behavioral sequelae following acute diisopropylfluorophosphate intoxication in rats: comparative effects of atropine and cannabinomimetics. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2010;32(3):329–335. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhong P, Wang W, Pan B, Liu X, Zhang Z, Long JZ, Zhang HT, Cravatt BF, Liu QS. Monoacylglycerol Lipase Inhibition Blocks Chronic Stress-Induced Depressive-Like Behaviors via Activation of mTOR Signaling. Neuropsycho-pharmacology. 2014 doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vinod KY, Kassir SA, Hungund BL, Cooper TB, Mann JJ, Arango V. Selective alterations of the CB1 receptors and the fatty acid amide hydrolase in the ventral striatum of alcoholics and suicides. J. Psychiatry Res. 2010;44(9):591–597. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cao X, Liu Z, Xu C, Li J, Gao Q, Sun N, Xu Y, Ren Y, Yang C, Zhang K. Disrupted resting-state functional connectivity of the hippocampus in medication-naive patients with major depressive disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2012;141(2-3):194–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Robinson OJ, Cools R, Carlisi CO, Sahakian BJ, Drevets WC. Ventral striatum response during reward and punishment reversal learning in unmedicated major depressive disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2012;169(2):152–159. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11010137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Micale V, Di Marzo V, Sulcova A, Wotjak CT, Drago F. Endocannabinoid system and mood disorders priming a target for new therapies. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013;138(1):18–37. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Marsicano G, Lutz B. Expression of the cannabinoid receptor CB1 in distinct neuronal subpopulations in the adult mouse forebrain. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1999;11(12):4213–4225. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Giuffrida A, Parsons LH, Kerr TM, Rodriguez de Fonseca F, Navarro M, Piomelli D. Dopamine activation of endogenous cannabinoid signaling in dorsal striatum. Nat. Neurosci. 1999;2(4):358–363. doi: 10.1038/7268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Centonze D, Battista N, Rossi S, Mercuri NB, Finazzi-Agro A, Bernardi G, Calabresi P, Maccarrone M. A critical interaction between dopamine D2 receptors and endocannabinoids mediates the effects of cocaine on striatal gabaergic Transmission. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29(8):1488–1497. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gardner EL. Endocannabinoid signaling system and brain reward emphasis on dopamine. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2005;81(2):263–284. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mikics E, Vas J, Aliczki M, Halasz J, Haller J. Interactions between the anxiogenic effects of CB1 gene disruption and 5-HT3 neurotransmission. Behav. Pharmacol. 2009;20(3):265–272. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32832c70b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sanchis-Segura C, Cline BH, Marsicano G, Lutz B, Spanagel R. Reduced sensitivity to reward in CB1 knockout mice. sycho-pharmacology (Berl) 2004;176(2):223–232. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1877-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aso E, Ozaita A, Valdizán EM, Ledent C, Pazos A, Maldonado R, Valverde O. BDNF impairment in the hippocampus is related to enhanced despair behavior in CB1 knockout mice. J. Neurochem. 2008;105(2):565–572. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Steiner MA, Marsicano G, Nestler EJ, Holsboer F, Lutz B, Wotjak CT. Antidepressant-like behavioral effects of impaired cannabinoid receptor type 1 signaling coincide with exaggerated corticosterone secretion in mice. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33(1):54–67. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Valverde O, Torrens M. CB1 receptor-deficient mice as a model for depression. Neuroscience. 2012;204:193–206. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hill MN, Patel S, Carrier EJ, Rademacher DJ, Ormerod BK, Hillard CJ, Gorzalka BB. Downregulation of endocannabinoid signaling in the hippocampus following chronic unpredictable stress. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30(3):508–515. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Reyes Prieto NM, Romano Lopez A, Perez Morales M, Pech O, Mendez-Diaz M, Ruiz Contreras AE, Prospero-Garcia O. Oleamide restores sleep in adult rats that were subjected to maternal separation. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2012;103(2):308–312. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2012.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Romano-Lopez A, Mendez-Diaz M, Ruiz-Contreras AE, Carrisoza R, Prospero-Garcia O. Maternal separation and proclivity for ethanol intake: a potential role of the endocannabinoid system in rats. Neuroscience. 2012;223:296–304. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Marco EM, Valero M, de la Serna O, Aisa B, Borcel E, Ramirez MJ, Viveros MP. Maternal deprivation effects on brain plasticity and recognition memory in adolescent male and female rats. Neuropharmacology. 2013;68:223–231. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lopez-Gallardo M, Lopez-Rodriguez AB, Llorente-Berzal A, Rotllant D, Mackie K, Armario A, Nadal R, Viveros MP. Maternal deprivation and adolescent cannabinoid exposure impact hippocampal astrocytes, CB1 receptors and brain-derived neurotrophic factor in a sexually dimorphic fashion. Neuroscience. 2012;204:90–103. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.09.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Suarez J, Llorente R, Romero-Zerbo SY, Mateos B, Bermudez-Silva FJ, de Fonseca FR, Viveros MP. Early maternal deprivation induces gender-dependent changes on the expression of hippocampal CB(1) and CB(2) cannabinoid receptors of neonatal rats. Hippocampus. 2009;19(7):623–632. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.McLaughlin RJ, Hill MN, Dang SS, Wainwright SR, Galea LA, Hillard CJ, Gorzalka BB. Upregulation of CB(1) receptor binding in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex promotes proactive stress-coping strategies following chronic stress exposure. Behav. Brain Res. 2013;237:333–337. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.09.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rodriguez-Gaztelumendi A, Rojo ML, Pazos A, Diaz A. Altered CB receptor-signaling in prefrontal cortex from an animal model of depression is reversed by chronic fluoxetine. J. Neurochem. 2009;108(6):1423–1433. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.05898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.El-Alfy AT, Ivey K, Robinson K, Ahmed S, Radwan M, Slade D, Khan I, ElSohly M, Ross S. Antidepressant-like effect of delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol and other cannabinoids isolated from Cannabis sativa L. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2010;95(4):434–442. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Haring M, Grieb M, Monory K, Lutz B, Moreira FA. Cannabinoid CB(1) receptor in the modulation of stress coping behavior in mice the role of serotonin and different forebrain neuronal subpopulations. Neuropharmacology. 2013;65:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Morrish AC, Hill MN, Riebe CJ, Gorzalka BB. Protracted cannabinoid administration elicits antidepressant behavioral responses in rats: role of gender and noradrenergic transmission. Physiol. Behav. 2009;98(1-2):118–124. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rubino T, Vigano D, Realini N, Guidali C, Braida D, Capurro V, Castiglioni C, Cherubino F, Romualdi P, Candeletti S, Sala M, Parolaro D. Chronic delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol during adolescence provokes sex-dependent changes in the emotional profile in adult rats behavioral and biochemical correlates. Neuro- psychopharmacology. 2008;33(11):2760–2771. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bambico FR, Nguyen NT, Katz N, Gobbi G. Chronic exposure to cannabinoids during adolescence but not during adunglthood impairs emotional behaviour and monoaminergic neurotransmission. Neurobiol. Dis. 2010;37(3):641–655. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Egashira N, Matsuda T, Koushi E, Higashihara F, Mishima K, Chidori S, Hasebe N, Iwasaki K, Nishimura R, Oishi R, Fujiwara M. Delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol prolongs the immobility time in the mouse forced swim test involvement of cannabinoid CB(1) receptor and serotonergic system. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2008;589(1-3):117–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tzavara ET, Davis RJ, Perry KW, Li X, Salhoff C, Bymaster FP, Witkin JM, Nomikos GG. The CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716A selectively increases monoaminergic neurotransmission in the medial prefrontal cortex implications for therapeutic actions. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2003;138(4):544–553. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Takahashi E, Katayama M, Niimi K, Itakura C. Additive subthreshold dose effects of cannabinoid CB(1) receptor antagonist and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor in antidepressant behavioral tests. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2008;589(1-3):149–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Griebel G, Stemmelin J, Scatton B. Effects of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist rimonabant in models of emotional reactivity in rodents. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57(3):261–267. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Beyer CE, Dwyer JM, Piesla MJ, Platt BJ, Shen R, Rahman Z, Chan K, Manners MT, Samad TA, Kennedy JD, Bingham B, Whiteside GT. Depression-like phenotype following chronic CB1 receptor antagonism. Neurobiol. Dis. 2010;39(2):148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lee S, Kim DH, Yoon SH, Ryu JH. Sub-chronic administration of rimonabant causes loss of antidepressive activity and decreases doublecortin immunoreactivity in the mouse hippocampus. Neurosci. Lett. 2009;467(2):111–116. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Verty AN, Lockie SH, Stefanidis A, Oldfield BJ. Anti-obesity effects of the combined administration of CB1 receptor antagonist rimonabant and melanin-concentrating hormone antagonist SNAP-94847 in diet-induced obese mice. Int. J. Obes. (Lond) 2013;37(2):279–287. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shearman LP, Rosko KM, Fleischer R, Wang J, Xu S, Tong XS, Rocha BA. Antidepressant-like and anorectic effects of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor inverse agonist AM251 in mice. Behav. Pharmacol. 2003;14(8):573–582. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200312000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mato S, Vidal R, Castro E, Diaz A, Pazos A, Valdizan EM. Long-term fluoxetine treatment modulates cannabinoid type 1 receptor-mediated inhibition of adenylyl cyclase in the rat prefrontal cortex through 5-hydroxytryptamine 1A receptor-dependent mechanisms. Mol. Pharmacol. 2010;77(3):424–434. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.060079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hesketh SA, Brennan AK, Jessop DS, Finn DP. Effects of chronic treatment with citalopram on cannabinoid and opioid receptor-mediated G-protein coupling in discrete rat brain regions. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2008;198(1):29–36. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-1033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Aso E, Renoir T, Mengod G, Ledent C, Hamon M, Maldonado R, Lanfumey L, Valverde O. Lack of CB1 receptor activity impairs serotonergic negative feedback. J. Neurochem. 2009;109(3):935–944. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kleijn J, Cremers TI, Hofland CM, Westerink BH. CB-1 receptors modulate the effect of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, citalopram on extracellular serotonin levels in the rat prefrontal cortex. Neurosci. Res. 2011;70(3):334–337. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mato S, Aso E, Castro E, Martin M, Valverde O, Maldonado R, Pazos A. CB1 knockout mice display impaired functionality of 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A/C receptors. J. Neurochem. 2007;103(5):2111–2120. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Koethe D, Llenos IC, Dulay JR, Hoyer C, Torrey EF, Leweke FM, Weis S. Expression of CB1 cannabinoid receptor in the anterior cingulate cortex in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression. J. Neural Transm. 2007;114(8):1055–1063. doi: 10.1007/s00702-007-0660-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Choi K, Le T, McGuire J, Xing G, Zhang L, Li H, Parker CC, Johnson LR, Ursano RJ. Expression pattern of the cannabinoid receptor genes in the frontal cortex of mood disorder patients and mice selectively bred for high and low fear. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2012;46(7):882–889. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hungund BL, Vinod KY, Kassir SA, Basavarajappa BS, Yalamanchili R, Cooper TB, Mann JJ, Arango V. Upregulation of CB1 receptors and agonist-stimulated [35S] GTPgammaS binding in the prefrontal cortex of depressed suicide victims. Mol. Psychiatry. 2004;9(2):184–190. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Christensen R, Kristensen PK, Bartels EM, Bliddal H, Astrup A. Efficacy and safety of the weight-loss drug rimonabant a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2007;370(9600):1706–1713. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61721-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Horder J, Cowen PJ, Di Simplicio M, Browning M, Harmer CJ. Acute administration of the cannabinoid CB1 antagonist rimonabant impairs positive affective memory in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2009;205(1):85–91. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1517-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Addy C, Rothenberg P, Li S, Majumdar A, Agrawal N, Li H, Zhong L, Yuan J, Maes A, Dunbar S, Cote J, Rosko K, Van Dyck K, De Lepeleire I, de Hoon J, Van Hecken A, Depre M, Knops A, Gottesdiener K, Stoch A, Wagner J. Multiple-dose pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and safety of taranabant, a novel selective cannabinoid-1 receptor inverse agonist, in healthy male volunteers. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008;48(6):734–744. doi: 10.1177/0091270008317591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Addy C, Li S, Agrawal N, Stone J, Majumdar A, Zhong L, Li H, Yuan J, Maes A, Rothenberg P, Cote J, Rosko K, Cummings C, Warrington S, Boyce M, Gottesdiener K, Stoch A, Wagner J. Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamic properties of taranabant, a novel selective cannabinoid-1 receptor inverse agonist, for the treatment of obesity results from a double-blind, placebo-controlled, single oral dose study in healthy volunteers. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008;48(4):418–427. doi: 10.1177/0091270008314467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Onaivi ES, Ishiguro H, Gong JP, Patel S, Meozzi PA, Myers L, Perchuk A, Mora Z, Tagliaferro PA, Gardner E, Brusco A, Akinshola BE, Liu QR, Chirwa SS, Hope B, Lujilde J, Inada T, Iwasaki S, Macharia D, Teasenfitz L, Arinami T, Uhl GR. Functional expression of brain neuronal CB2 cannabinoid receptors are involved in the effects of drugs of abuse and in depression. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008;1139:434–449. doi: 10.1196/annals.1432.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hu B, Doods H, Treede RD, Ceci A. Depression-like behaviour in rats with mononeuropathy is reduced by the CB2-selective agonist GW405833. Pain. 2009;143(3):206–212. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Navarrete F, Perez-Ortiz JM, Manzanares J. Cannabinoid CB(2) receptor-mediated regulation of impulsive-like behaviour in DBA/2 mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012;165(1):260–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01542.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gong JP, Onaivi ES, Ishiguro H, Liu QR, Tagliaferro PA, Brusco A, Uhl GR. Cannabinoid CB2 receptors immuno-histochemical localization in rat brain. Brain Res. 2006;1071(1):10–23. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Garcia-Gutierrez MS, Perez-Ortiz JM, Gutierrez-Adan A, Manzanares J. Depression-resistant endophenotype in mice overexpressing cannabinoid CB(2) receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2010;160(7):1773–1784. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00819.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Onaivi ES, Ishiguro H, Gong JP, Patel S, Meozzi PA, Myers L, Perchuk A, Mora Z, Tagliaferro PA, Gardner E, Brusco A, Akinshola BE, Hope B, Lujilde J, Inada T, Iwasaki S, Macharia D, Teasenfitz L, Arinami T, Uhl GR. Brain neuronal CB2 cannabinoid receptors in drug abuse and depression from mice to human subjects. PLoS One. 2008;3(2):e1640. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Starowicz K, Cristino L, Di Marzo V. TRPV1 receptors in the central nervous system potential for previously unforeseen therapeutic applications. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2008;14(1):42–54. doi: 10.2174/138161208783330790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Khairatkar-Joshi N, Szallasi A. TRPV1 antagonists the challenges for therapeutic targeting. Trends Mol. Med. 2009;15(1):14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kofalvi A, Pereira MF, Rebola N, Rodrigues RJ, Oliveira CR, Cunha RA. Anandamide and NADA bi-directionally modulate presynaptic Ca2+ levels and transmitter release in the hippocampus. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2007;151(4):551–563. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.You IJ, Jung YH, Kim MJ, Kwon SH, Hong SI, Lee SY, Jang CG. Alterations in the emotional and memory behavioral phenotypes of transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1-deficient mice are mediated by changes in expression of 5-HT(1)A, GABA(A) and NMDA receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62(2):1034–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hayase T. Differential effects of TRPV1 receptor ligands against nicotine-induced depression-like behaviors. BMC Pharmacol. 2011;11:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2210-11-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Manna SS, Umathe SN. A possible participation of transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 channels in the antidepressant effect of fluoxetine. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2012;685(1-3):81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kulisch C, Albrecht D. Effects of single swim stress on changes in TRPV1-mediated plasticity in the amygdala. Behav. Brain Res. 2013;236(1):344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kasckow JW, Mulchahey JJ, Geracioti TD. Effects of the vanilloid agonist olvanil and antagonist capsazepine on rat behaviors. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2004;28(2):291–295. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Benarroch EE. The locus ceruleus norepinephrine system functional organization and potential clinical significance. Neurology. 2009;73(20):1699–1704. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c2937c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]