Summary

The fungal meningitis pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans is a central driver of mortality in HIV/AIDS. We report a genome-scale chemical genetic data map for this pathogen that quantifies the impact of 439 small molecule challenges on 1448 gene knockouts. We identified chemical phenotypes for 83% of mutants screened and at least one genetic response for each compound. C. neoformans chemical-genetic responses are largely distinct from orthologous published profiles of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, demonstrating the importance of pathogen-centered studies. We used the chemical-genetic matrix to predict novel pathogenicity genes, infer compound mode-of-action, and to develop an algorithm, O2M, that predicts antifungal synergies. These predictions were experimentally validated, thereby identifying virulence genes, a molecule that triggers G2/M arrest and inhibits the Cdc25 phosphatase, and many compounds that synergize with the antifungal drug fluconazole. Our work establishes a chemical-genetic foundation for approaching an infection responsible for greater than one-third of AIDS-related deaths.

Introduction

Invasive fungal infections are notoriously difficult to diagnose and treat, resulting in high mortality rates, even with state-of-the art treatments. The three most common pathogenic agents are Cryptococcus neoformans, Candida albicans, Aspergillus fumigatus (Mandell et al., 2010). These organisms are opportunistic fungi that prey on individuals with varying degrees of immune deficiency. Susceptible patient populations include premature infants, diabetics, individuals with liver disease, chemotherapy patients, organ transplant recipients, and those infected with HIV (Mandell et al., 2010). Compounding the clinical challenge is the slow pace of antifungal drug development: only a single new class of drugs (the echinocandins) has been approved for use in the United States in the last 30 years (Butts and Krysan, 2012; Mandell et al., 2010; Roemer et al., 2011).

Fungal infections are estimated to cause 50% of deaths related to Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS), and have been termed a “neglected epidemic” (Armstrong-James et al., 2014). The fungus chiefly responsible for deaths in this population is Cryptococcus neoformans (Armstrong-James et al., 2014). C. neoformans is an encapsulated basidiomycetous haploid yeast distantly related Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe. A 2009 CDC study estimated that ~1 million infections and ~600,000 deaths annually are caused by Cryptococcus neoformans, exceeding the estimated worldwide death toll from breast cancer (Lozano et al., 2012; Park et al., 2009). Cryptococcus neoformans is widespread in the environment and exposure occurs through inhalation of desiccated yeast or spores (Heitman et al., 2011). In immunocompromised patients, C. neoformans replicates and disseminates, causing meningoencephalitis that is lethal without treatment (Heitman et al., 2011). Induction therapy involves flucytosine and intravenous infusions of amphtotericin B (Loyse et al., 2013). Both drugs are highly toxic, difficult to administer, and neither is readily available in the areas with the highest rates of disease. The current recommendation for Cryptococcosis treatment is at least a year of therapy, which is difficult to accomplish in resource-limited settings (WHO, 2011). Thus, as is the case with infections caused by other fungal pathogens, effective treatment of cryptococcal infections is limited by the efficacy, toxicity, and availability of current pharmaceuticals.

We implemented chemogenomic profiling to approach the challenges of therapeutic development in C. neoformans. This method involves the systematic measurement of the impact of compounds on the growth of defined null mutants to produce a chemical-genetic map. Such a map represents a quantitative description composed of numerical score indicative of the growth behavior of each knockout mutant under each chemical condition. Cluster analysis of the growth scores for large numbers of mutants under many chemical conditions can reveal genes that function in the same pathway and even those whose products are part of the same protein complex (Collins et al., 2007; Parsons et al., 2004; Parsons et al., 2006). In addition, the identity of genes whose mutation produce resistance or sensitivity is useful for uncovering compound mode-of-action (MOA) (Hillenmeyer et al., 2008; Jiang et al., 2008; Nichols et al., 2010; Parsons et al., 2006; Xu et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2009). Large-scale studies have been restricted to model organisms for which gene deletion collections have been constructed, namely S. cerevisiae, S. pombe, and Escherichia coli K12 (Hillenmeyer et al., 2008; Nichols et al., 2010; Parsons et al., 2006). However, as none of these are pathogens, the extent to which the resulting insights translate to pathogenic organisms is unknown. A variation on chemogenomic profiling, chemically-induced haploinsufficiency, was first developed using a diploid heterozygote gene deletion library S. cerevisiae to identify compound MOA. This method, which identifies genes that impact compound sensitivity based a two-fold gene dosage change, is suited for diploid organisms and has been used in the pathogen C. albicans (Jiang et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2009).

We report here the generation of a large-scale chemogenomic map for C. neoformans using defined, commonly available knockout mutants, assessments of data quality, and extensive experimental verification. Comparisons of the C. neoformans profile with two large-scale published profiles from S. cerevisiae revealed that for most types of compounds, the chemical-genetic interactions are distinct even among orthologous genes, emphasizing the importance of pathogen-focused investigation. We used nearest-neighbor analysis to predict new genes involved in polysaccharide capsule formation and infectivity, which we validated through experiment. We also utilized genetic responses to predict the G2/M phase of the cell cycle and the Cdc25 phosphatase as targets of a thiazolidone-2,4-dione derivative, which we confirmed in vivo and in vitro. Finally, because of the unmet need for improved antifungal drug efficacy, we developed a new algorithm, O2M, to predict new compound synergies based on the profiles of pairs known to be synergistic. Experimental tests demonstrate that the method performs vastly better than random expectation, thereby enabling the identification of synergistic compound combinations. Our studies establish a chemical-genetic foundation to approach the biology and treatments C. neoformans infections, which are responsible for more than one-third of HIV/AIDS deaths worldwide.

Results

A chemical-genetic map of C. neoformans

We assembled 1448 Cryptococcus neoformans gene deletion strains (Chun et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2008) (Table S1), corresponding to a substantial fraction of 6,967 predicted C. neoformans genes (Janbon et al., 2014), and a collection of compounds for screening (Table 1). Compounds were selected based on cost and literature evidence that they could inhibit the growth of fungi. Where feasible, compounds were chosen that are known to target specific biological processes. For each small molecule, we determined an approximate minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) in agar, then measured growth of the knockout collection on each small molecule at 50%, 25%, and 12.5% MIC using high density agar plate colony arrays and a robotic replicator. We then measured the size of each colony using flatbed scanning and colony measurement software (Dittmar et al., 2010). We performed a minimum of four replicate colony measurements for each mutant-condition pair. Plate-based assays are subject to known non-biological effects, such as spatial patterns. To mitigate these errors, a series of corrective measures were implemented using approaches described previously, including manual filtration of noisy data, spatial effect normalization and machine learning-based batch correction (Baryshnikova et al., 2010). In addition, the data for each deletion mutant and compound was centered and normalized. Each mutant-small molecule combination was assigned a score with positive scores representing relative resistance and negative scores representing compound sensitivity (Table S2). A global summary of the processed data organized by hierarchical clustering is shown in Fig. 1A.

Table 1. Small molecules and targets.

A list of compounds used in this study, their targets, and the screening concentration.

| Inhibitor (Activator) | Highest screening conc. | Process/enzyme | Category | Pubchem ID | FDA approval? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–10 phenanthroline hydrochloride monohydrate | 2uM | broad/transition metal complexes | broad spectrum | 2723715 | no |

| 2-aminobenzothiazole | 30uM | cytoskeleton function/kinesin Kip1 | cell structure | 8706 | no |

| 2-hydroxyethylhydrazine | 0.156% | lipid synthesis/phospholipid methylation | lipid biosynthesis | 8017 | no |

| 3-aminotriazole | 6.25mM | histidine synthesis/IMP dehydratase | metabolism | 1639 | no |

| 4-hydroxytamoxifen | 1.56uM | estrogen receptor (mammals) | signaling | 449459 | yes |

| 5-fluorocytosine | 2.5ug/ml | DNA/RNA biosynthesis | DNA homeostasis/protein synthesis | 3366 | yes |

| 5-methyltryptophan | 8mM | tryptophan synthesis | metabolism | 150990 | no |

| abietic acid | 1mM | lipid synthesis/lipoxygenase | lipid biosynthesis | 10569 | no |

| acifluorfen methyl | 156.25ng/ml | porphyrin synthesis/protoporphyrinogen oxidase | metabolism | 91642 | no |

| (aconitine) | 200ug/ml | membrane potential/Na+ channels (mammals) | membrane polarization | 245005 | no |

| aflatoxin B1 | 100ug/ml | DNA damaging agent | DNA homeostasis | 14403 | no |

| agelasine D | 5ug/ml | membrane potential/Na+/K+-ATPase (mammals) | membrane polarization | 46231918 | no |

| alamethicin/U-22324 | 60uM | membrane integrity/forms a voltage-depended ion channel | membrane polarization | 16132042 | no |

| alexidine dihydrochloride | 125ug/ml | anti-microbial/mitochondria | mitochondria | 102678 | yes |

| allantoin | 100ug/ml | nitrogen-rich compound | metabolism | 204 | topical |

| alternariol | 2.5ug/ml | cholinesterase inhibitor/sodium channel activator and DNA supercoiling/topoisomerase I | broad spectrum | 5359485 | no |

| alumininum sulfate | 1.5625mM | unknown | unknown | 24850 | no |

| (amantadine hydrochloride) | 1.25mM | neurotransmitter release/glutamate receptor | signaling | 64150 | yes |

| amiodarone | 60ug/ml | membrane potential/Na+/K+-ATPase (mammals) | membrane polarization | 2157 | yes |

| (ammonium persulfate) | 50mM | reactive oxygen species | apoptosis/stress response/damage response | 62648 | no |

| amphotericin B | 1ug/ml | lipid biosynthesis/ergosterol | membrane integrity | 5280965 | yes |

| andrastin A | 4ug/ml | protein modification/farnesyltransferase | protein trafficking | 6712564 | no |

| anisomycin | 50uM | translation/peptidyl transferase | gene expression | 253602 | no |

| antimycin | 100ug/ml | respiration/cytochrome B | metabolism | 14957 | no |

| apicidin | 312.5ng/ml | chromatin regulation/HDACs | gene expression | 6918328 | no |

| artemisinin | 312.5mM | iron metabolism/hematin detoxification | metabolism | 68827 | yes |

| ascomycin | 3.125uM | signaling/calcineurin | signaling | 6437370 | yes |

| azide | 62.5uM | respiration/cytochrome C oxidase | metabolism | 33558 | no |

| barium chloride | 16mM | metal homeostasis/diverse | broad spectrum/unknown | 25204 | no |

| bafilomycin | 4ug/ml | autophagy/vacuolar-type H+-ATPase | protein turnover | 6436223 | no |

| bathocuproine disulphonic acid (BCS) | 3mM | copper acquisition | metabolism | 16211287 | no |

| bathophenanthroline disulfonate (BPS) | 300uM | iron acquistion/Fet3-Ftr1 | metabolism | 65368 | no |

| benomyl | 100ug/ml | cytoskeleton function/tubulin | cell structure | 28780 | no |

| (betulinic acid) | 64ug/ml | protein degradation/proteasome | protein turnover | 64971 | no |

| bifonazole | 50ug/ml | lipid biosynthesis/HMG-CoA and ergosterol biosynthesis | membrane integrity | 2378 | no |

| brefeldin A | 40ug/ml | ER-Golgi Transport/ARF GEF | secretion | 5287620 | no |

| calcium chloride | 16mM | metal homeostasis/diverse | broad spectrum | 5284359 | no |

| caffeine | 2.5mM | DNA damage checkpoint/ATM | DNA homeostasis | 2519 | no |

| calcium ionophore A23187 | 2.5ug/ml | membrane integrity/peptide that acts as ionophore | membrane integrity | 40486 | no |

| calcofluor white | 500ug/ml | cell wall synthesis/chitin and cellulose | cell wall | 6108780 | no |

| camptothecin | 500ug/ml | DNA supercoiling/topoisomerase I | DNA homeostasis | 24360 | analog |

| castanospermine | 2.4mM | protein modification/glycosidation | protein modification | 54445 | derivative |

| cadmium chloride | 1mM | metal homeostasis/diverse | broad spectrum/un known | 24947 | no |

| cerulenin | 312.5ng/ml | fatty acid synthesis/beta-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase | lipid biosynthesis | 5282054 | no |

| cesium chloride | 128mM | metal homeostasis/diverse | broad spectrum/unknown | 24293 | no |

| chlorpromazine hydrochloride | 1.5625uM | phenothiazine antipsychotic drug (mammals)/dopamine, seratonin, and other neuroreceptors | signaling | 6240 | yes |

| chromium (III) chloride | 8mM | metal homeostasis/diverse | broad spectrum | 16211596 | no |

| ciclopirox olamine | 750ng/ml | iron acquisition and other | metabolism | 38911 | yes |

| cisplatin | 100ug/ml | DNA synthesis | DNA homeostasis | 157432 | yes |

| climbazole | 0.03125% | lipid biosynthesis/ergosterol biosynthesis and respiration/cytochrome P450 | broad spectrum | 37907 | topical |

| clotrimazole | 500nM | lipid biosynthesis/ergosterol biosynthesis | membrane integrity | 2812 | yes |

| colistin | 1mg/ml | membrane integrity | membrane integrity | 5311054 | yes |

| congo red | 0.0625% | cell wall synthesis/chitin, cellulose, and glucan | cell wall | 11313 | no |

| coniine | 0.15625% | neurosignaling (mammals)/nicotinic receptor | signaling | 441072 | no |

| (crystal violet) | 0.0012500% | oxidative stress inducer | stress response | 11057 | topical |

| CuCl2 | 8mM | copper homeostasis/diverse | metabolism | 24014 | no |

| cycloheximide | 1.875ug/ml | translation/ribosome | gene expression | 6197 | no |

| cyclopiazonic acid | 15.625uM | ion transport and cell polarization (mammals)/Ca2+- ATPase | metabolism | 54682463 | no |

| cyclosporin | 75ug/ml | signaling/calcineurin | signaling | 5284373 | yes |

| cyproconazole | 1.5625ug/ml | lipid biosynthesis/ergosterol biosynthesis | membrane integrity | 86132 | no |

| cyprodinil | 10ug/ml | methionine biosynthesis | metabolism | 86367 | no |

| daphnetin | 100uM | signaling/PKA, PKC, EGR receptor, others | signaling | 5280569 | no |

| desipramine hydrochloride | 250uM | neurosignaling (mammals)/norepinephrine transporter | signaling | 65327 | yes |

| dyclonine hydrochloride | 3.125uM | lipid biosynthesis/ergosterol biosynthesis | membrane integrity | 68304 | yes |

| emetine dihydrochloride hydrate | 5mM | translation/ribosome | gene expression | 3068143 | yes |

| emodin | 62.5uM | signaling/CK2, others | signaling | 3220 | yes |

| erlotinib | 50ug/ml | signaling (mammals)/EGFR tyrosine kinase | signaling | 176870 | yes |

| FeCl3 | 32mM | iron acquisition, metal homeostasis | metabolism | 24380 | no |

| fenoxanil | 80ug/ml | melanin biosynthesis | metabolism | 11262655 | no |

| fenpropimorph | 2.5ug/ml | sterol synthesis | lipid biosynthesis | 93365 | no |

| FK506 | 312.5ng/ml | signaling/calcineurin | signaling | 445643 | yes |

| fluconazole | 10ug/ml | lipid biosynthesis/ergosterol biosynthesis | membrane integrity | 3365 | yes |

| fluspirilene | 25uM | antipsychotic drug, mechanism of action unknown | unknown | 3396 | yes |

| gallium (III) nitrate | 25mM | metal homeostasis/diverse | broad spectrum | 57352728 | no |

| geldanamycin | 2uM | protein folding/Hsp90 | protein folding | 5288382 | trials |

| (H2O2) | 6mM | reactive oxygen species | apoptosis/stress response/damage response | 784 | topical |

| haloperidol | 125uM | phenothiazine antipsychotic drug (mammals)/dopamine, seratonin, and other neuroreceptors | signaling | 3559 | yes |

| harmine hydrochloride | 1mM | cell differentiation (mammals)/PPARgamma | signaling | 5359389 | yes |

| hydroxyurea | 12.5mM | DNA replication/replication fork progression | DNA homeostasis | 3657 | yes |

| hygromycin | 37.5ug/ml | translation/ribosome | gene expression | 35766 | no |

| imazalil | 25ug/ml | lipid biosynthesis/ergosterol synthesis | membrane integrity | 37175 | no |

| iodoacetate | 500uM | protein degradation/cysteine peptidases | protein turnover | 5240 | no |

| itraconazole | 1.5625ug/ml | lipid biosynthesis/ergosterol synthesis | membrane integrity | 55283 | yes |

| K252a | 10ug/ml | signaling/variety of kinases | signaling | 127357 | trials |

| latrunculin | 25uM | cytoskeleton function/actin | cell structure | 445420 | no |

| lead (II) nitrate | 64mM | metal homeostasis/diverse | broad spectrum | 24924 | no |

| leptomycin | 1.25ug/ml | nucleocytoplasmic transport/Crm1 | gene expression | 6917907 | no |

| LiCl | 37.5mM | metal homeostasis/diverse | broad spectrum/un known | 433294 | no |

| lovastatin | 37.5ug/ml | sterol synthesis/HMG CoA reductase | metabolism | 53232 | yes |

| LY 294002 | 375uM | signaling/PI3K | signaling | 3973 | no |

| magnesium chloride | 150mM | metal homeostasis/diverse | broad spectrum | 21225507 | no |

| malachite green | 3.125ug/ml | anti-microbial/unknown | anti-microbial | 11294 | no |

| manganese sulfate | 128mM | metal homeostasis/diverse | metabolism | 177577 | no |

| mastoparan | 5uM | signaling/G-proteins | signaling | 5464497 | no |

| (menadione) | 150uM | vitamin K3/reactive oxygen species | diverse | 4055 | yes |

| menthol | 1mM | voltage-dependent ion channels (mammals)/sodium channel | signaling | 16666 | yes |

| methotrexate | 2.5uM | folate synthesis/DHFR | metabolism | 126941 | yes |

| methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) | 0.0165% | DNA replication/replication fork progression | DNA homeostasis | 4156 | no |

| methylbenzethonium chloride (MBT) | 0.25% | anti-microbial | anti-microbial | 5702238 | topical |

| MG132 | 12.5uM | protein degradation/proteasome | protein turnover | 462382 | no |

| miconazole | 6.25ug/ml | lipid biosynthesis/ergosterol synthesis | membrane integrity | 4189 | yes |

| mitomycin C | 12uM | DNA damaging agent | DNA homeostasis | 5746 | yes |

| myclobutanil | 2ug/ml | lipid biosynthesis/ergosterol synthesis | membrane integrity | 6336 | no |

| mycophenolic acid | 2.5ug/ml | GMP synthesis/IMP dehydrogenase | metabolism | 446541 | yes |

| myriocin | 12.5ug/ml | sphingolipid synthesis | metabolism | 6438394 | analog |

| NA8 | unknown | unknown | no | ||

| (NaCl) | 37.5mM | osmotic regulation/HOG pathway | stress response | 5234 | yes |

| (NaNO2) | 150uM | reactive nitrogen species | stress response | 23668193 | no |

| neomycin sulfate | 2.4mM | protein synthesis/ribosome | gene expression | 8378 | yes |

| nicotinamide | 25uM | chromatin regulation/sirtuins | gene expression | 936 | yes |

| nigericin | 100ug/ml | membrane integrity/ion gradient | membrane polarization | 34230 | no |

| nikkomycin | 5ug/ml | chitin synthesis | cell wall | 72479 | trials |

| NiSO4 | 1mM | anti-fungal/diverse | anti-fungal | 5284429 | no |

| nocodazole | 30uM | cytoskeleton function/tubulin | cell structure | 4122 | no |

| ophiobolin A | 62.5ng/ml | signaling/calmodulin | signaling | 5281387 | no |

| parthenolide | 150uM | immune and inflammatory response/NF-kB | signaling | 6473881 | no |

| pentamidine isethionate | 500uM | anti-microbial/mitochondrial function | anti-microbial | 8813 | yes |

| pH | 8.0, 8.5, 9.0 | pH homeostasis | diverse | no | |

| phenylarsine oxide | 2.5uM | broad/XCXXCX protein phosphatases | broad spectrum | 4778 | no |

| picoxystrobin | 6.25ug/ml | quinone outside inhibitor class/fungal cytochrome bcI | mitochondria | 11285653 | no |

| (plumbagin) | 2.8uM | reactive oxygen species | stress response | 10205 | no |

| PMSF | 10mM | vacuolar proteolysis/proteinase B | signaling | 4784 | no |

| polyoxin B | 200ug/ml | chitin synthesis | cell wall | 3084093 | no |

| povidone iodine | 2% | anti-microbial | anti-microbial | 410087 | topical |

| prussian blue | 75mM | monocation chelator | metabolism | 16211064 | yes |

| quinic acid | 2mM | anti-microbial | anti-microbial | 6508 | no |

| rapamycin | 0.125uM | signaling/TOR kinases | signaling | 5284616 | yes |

| rubidium chloride | 150mM | potassium metabolism/competitor | metabolism | 62683 | no |

| rifamycin SV monosodium salt | 200ug/ml | RNA synthesis/RNA polymerase | gene expression | 6324616 | yes |

| S10 | unknown | unknown | no | ||

| S8 | unknown | unknown | no | ||

| S-aminoethyl-L-cysteine (thialysine) | 10uM | amino acid metabolism/lysine analog | metabolism | 20048 | no |

| SDS | 0.0015625 % | cell membrane integrity | membrane integrity | 3423265 | no |

| selumetinib | 150ug/ml | signaling/MAPK (ERK) | signaling | 10127622 | trials |

| sertraline | 15ug/ml | neurosignaling (mammals)/seratonin reuptake | neurosignaling | 68617 | yes |

| sodium azide | 62.5uM | respiration/cytochrome oxidase | mitochondria | 33557 | no |

| sodium borate | 10mM | anti-microbial/diverse | anti-microbial | 21749317 | no |

| sodium hydrosulfite | 6.25mM | anti-microbial, counteracts some anti-microbials | anti-microbial | 24489 | no |

| sodium iodide | 75mM | anti-microbial | anti-microbial | 5238 | yes |

| sodium metavanadate | 10mM | signaling/protein phosphotyrosine phosphatases | signaling | 4148882 | no |

| (sodium molybdate) | 64mM | respiration/oxygen uptake | diverse | 61424 | no |

| sodium selenite | 4mM | respiration/oxygen uptake | diverse | 16210997 | yes |

| sodium sulfite | 100mM | ATP synthesis and accumulation/unknown | metabolism | 24437 | no |

| sodium tungstate | 64mM | metal homeostasis/diverse | broad spectrum/unknown | 150191 | no |

| sorafenib | 100uM | signaling/VEGF tyrosine kinase | signaling | 216239 | yes |

| staurosporine | 3uM | signaling/PKC1 | signaling | 5279 | yes |

| (STF-62247) | 400uM | autophagy | protein turnover | 704473 | trials |

| sulfometuron methyl | 100ug/ml | branch chain amino acid synthesis/acetolactate synthase | metabolism | 52997 | no |

| suloctidil | 400uM | Ca2+ homeostasis in blood vessels (mammals)/putative Ca2+ channel blocker | vascular system/metabolism | 5354 | formerly |

| tamoxifen citrate | 10uM | estrogen signaling (mammals)/estrogen receptor, mixed agonist/antagonist | signaling | 2733525 | yes |

| taurolidine | 0.01% | anti-microbial/lipopolysaccharide detection and signaling | host defense | 29566 | yes |

| tautomycin | 250nM | signaling/PP2A | signaling | 3034761 | no |

| tellurite | 0.1% | sulfate assimilation | metabolism | 115037 | no |

| terbinafine | 75uM | sterol synthesis/squalene epoxidase | metabolism | 1549008 | yes |

| thiabendazole | 200ug/ml | respiration/NADH oxidase | mitochondria | 5430 | yes |

| thonzonium bromide | 25uM | anti-microbial, pH homeostasis/V-ATPase | broad spectrum | 11102 | yes |

| tomatine | 5ug/ml | glycoalkaloid anti-fungal of unknown mechanism/ergosterol biosynthesis | anti-fungal/membrane integrity | 28523 | no |

| trichostatin A | 100uM | chromatin regulation/HDACs | gene expression | 444732 | no |

| trifluoperazine | 200uM | signaling/calmodulin | signaling | 5566 | yes |

| trimethoprim | 1.6mg/ml | folate synthesis/DHFR | metabolism | 5578 | yes |

| tunicamycin | 2.5ug/ml | glycosylation/Alg7 | secretion | 11104835 | no |

| usnic acid | 25ug/ml | anti-microbial | anti-microbial | 6433557 | trials |

| valinomycin | 20uM | membrane integrity/potassium exclusion | membrane polarization | 5649 | no |

| verrucarin | 5uM | protein biosynthesis/polysome | protein turnover | 6437060 | no |

| ZnCl2 | 4mM | metal homeostasis/diverse | diverse | 5727 | no |

Figure 1. Chemical-genetic profiling of C. neoformans.

A) Heat map of full dataset following hierarchical clustering. Compounds are arrayed on the x-axis and gene knockouts on the y-axis. See also Tables S1–S2.

B) Probability density function for pairwise correlation scores between the chemical genetic profiles of different compounds (grey) and the same compounds at different concentrations (purple) screened on different days (different batches).Scores between the chemical-genetic profiles of different concentrations of the same compounds are significantly higher than those between different compounds (Wilcoxon test, p = 2.7 × 10−176). See also Fig. S1.

C) Probability density function for pairwise correlation scores between the chemical genetic profiles of different compounds (grey) and azole family compounds (purple). Pairwise comparisons between azoles exhibit higher correlation scores than non-azole compounds (Wilcoxon test, p = 2.8 × 10−6). Molecules with the highest pairwise comparisons scores are listed on the right.

D) Pearson’s correlation score between two different concentrations of the same compounds. Concentrations with similar correlation scores are binned together (y-axis). For compounds with the greatest correlation scores between concentrations, Venn diagrams of significant genes (Z < −2.5) present in profiles from the same compounds at different concentrations and the small molecule structure are shown. The orange line indicates a hypergeometric p-value ≤ 0.05

E) Distribution of the number of significant phenotypes for each knockout mutant. Significant is considered |Z| > 2.5 and we identified significant phenotypes independently for each small molecule concentration. Knockout mutants with similar numbers of significant phenotypes are binned together (x-axis).

F) Distribution of the number of significant phenotypes (|Z| > 2.5) for each small molecule condition/concentration. Molecules with similar numbers of significant phenotypes were binned together (x-axis) and the # phenotypes per bin is shown on the y-axis. Bin range on the x-axis is 0, 1–5, 6–10, etc.

The importance and validity of the computational corrections is shown in Fig. 1B and Fig. S1. We estimated how reproducible the chemical-genetic profiles were by calculating the correlation scores for data obtained for different concentrations of the same small molecule (purple). This measures the degree of overlap between the overall chemical-genetic profiles, which are themselves each composed of a score for each mutant-small molecule combination. We found significant correlation (p = 2.67 × 10−176) between data obtained for different concentrations of the same small molecule compared to those between profiles generated by dataset randomization, suggesting significant reproducibility. Moreover, correlation scores between chemical-genetic profiles of different concentrations of different compounds (gray) are centered at approximately zero (Fig. 1B). This difference in correlation scores is apparent even when comparing experiments performed on the same day, when spurious batch signal can contribute to false positives (Baryshnikova et al., 2010). Our batch-correction algorithms resulted in same-batch screening data with strong positive correlation scores for the same compounds but correlation scores close to zero for different compounds (Fig. S1), demonstrating successful removal of spurious signal (Baryshnikova et al., 2010). We compared chemical-genetic profiles between compounds in the azole family (Fig. 1C). Despite the fact that the azoles tested includes those of diverse uses, from agricultural pesticides to FDA-approved drugs (Table 1), many exhibit a significant profile correlation (p = 2.82 × 10−6), further indicating significant signal in the data. As a final assessment, we performed hypergeometric testing across all compounds to determine whether the same sensitive gene knockouts (defined by Z < −2.5) are identified at different concentrations of the same compounds. Using a Bonferonni-corrected p-value cutoff, nearly all compounds display significant overlap of responsive genes at different concentrations (Fig. 1D).

We assigned at least one phenotype (sensitivity or resistance to a compound) to 1198 of 1448 mutants (Fig. 1E, Table S2–S4). Of these, 855 exhibit one to ten phenotypes, while remaining 343 displayed from 11 to 146 phenotypes. Gene deletions with the greatest number of phenotypes are cnag_07622Δ (encoding the COP9 signalosome subunit 1) and cnag_05748Δ (encoding a N to 1 subunit of the NuA3 histone acetyltransferase). Compounds that elicit the greatest number of responsive gene deletions (Fig. 1F) are the heavy metal salt sodium tungstate and the trichothecene protein synthesis inhibitor verrucarin (Table S5), presumably reflecting the pleiotropic impact of these molecules on cells.

Gene Ontology analysis reveals processes associated with drug sensitivity

Drug influx and efflux is thought to be a major general determinant of microbial drug susceptibility (Fernández and Hancock, 2012), but we also sought functions involved in drug sensitivity. We investigated this question in an unbiased fashion by analyzing chemogenomic profiles using Gene Ontology (GO), a gene annotation approach useful for comparative analyses. We first identified annotated orthologs of C. neoformans genes represented in the deletion library and associated GO terms with these orthologs. We then determined whether the sensitive gene knockouts that respond to each small molecule are enriched for association with particular GO terms relative to a randomized control set (Fig. 2, Table S6). We observed that protein transport-related terms are highly enriched, as are processes related to ubiquitin modification/proteolysis and vesicle-mediated transport. These terms are associated with nine and five compounds, respectively, suggesting that intracellular transport and ubiquitin-mediated protein turnover may play important general roles in drug sensitivity.

Figure 2. Determinants of compound sensitivity.

We calculated whether molecules elicited a significant response from C. neoformans ORFs that are enriched for association with specific GO terms. Terms are listed on the y-axis and the number of compounds whose responding gene knockouts associated with that GO term are listed on the x-axis. See also Table S6.

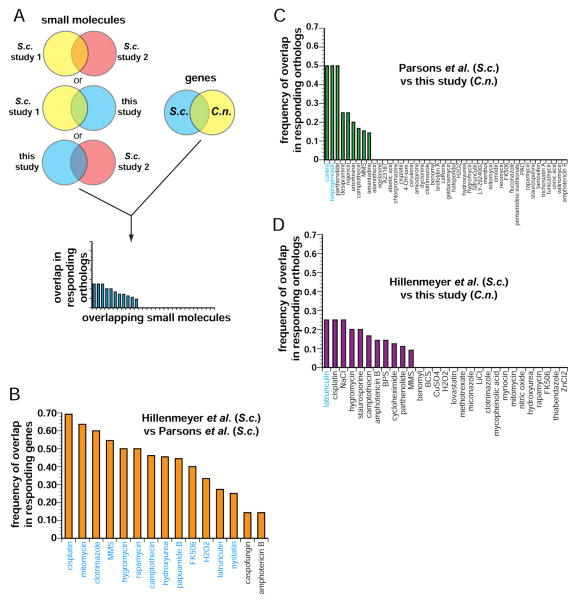

Comparison with S. cerevisiae chemogenomic profiling datasets

Chemogenomic profiling has been performed extensively in S. cerevisiae, allowing us to ask whether genetic responses to compounds were conserved. We performed a three-way comparison with two large-scale studies (Hillenmeyer et al., 2008; Parsons et al., 2006) (Fig. 3A). Our dataset has 46 compounds in common with Parsons et al. and 29 with Hillenmeyer et al.; the two S. cerevisiae datasets had 15 compounds in common. First we identified genes whose knockouts exhibited a significant (Z ≤ −2.5 or ≥ +2.5) score (“responding”) when treated with a small molecule used in more than one dataset, then identified which of those genes had orthologs in both S. cerevisiae and C. neoformans. We then calculated how many orthologs responded in both datasets. To adjust for a greater starting number of common genes when comparing the S. cerevisiae datasets to each other and control for functional biases, we limited this comparison to genes that also have orthologs in the C. neoformans knockout collection. The blue labels for compounds in Fig. 3B–D indicate statistically significant similarities (p ≤ 0.05) in drug responses. Nearly all of the compounds in common between the two S. cerevisiae studies display statistically significant overlap in the genes that produced sensitivity to a given compound, despite the very different experimental platforms were used to assess drug sensitivity/resistance (13/15 cases; Fig. 3B). In striking contrast, few compounds show significantly conserved genetic responses when comparing either S. cerevisiae dataset with the C. neoformans data. For the two C. neoformans-S. cerevisiae comparisons, only two of 46 compounds (Fig. 3C) and one of 29 compounds (Fig. 3D) show conserved responses, respectively.

Figure 3. Chemical-genetic signatures of C. neoformans genes differ from orthologous S. cerevisiae genes.

A) Flowchart of computation process for comparing datasets. We identified C. neoformans and S. cerevisiae orthologous genes that were present in all datasets, then compared the responses of only those genes in all the datasets. We compared genes whose knockout mutants significantly (|Z| > 2.5) responded to compound that were common in at least two of the datasets.

B) Comparison between Parsons et al. and Hillenmeyer et al., comparing the response (|Z| > 2.5) of genes that have orthologs present in the C. neoformans dataset. Compounds whose profiles exhibit significant overlaps (p < 0.05) are labeled in blue.

C) Comparison between our dataset and Parsons et al. Compounds whose profiles exhibit significant overlaps (p < 0.05) are labeled in blue.

D) Comparison between our dataset and Hillenmeyer et al. Compounds whose profiles exhibit significant overlaps (p < 0.05) are labeled in blue.

The responses to azole compounds exhibit limited response conservation between species. Comparing our dataset with Parsons et al., the responses to fluconazole (FLC) and clotrimazole, the azoles in both datasets, do not show significant overlap (Fig. 3C). Likewise, between our dataset and Hillenmeyer et al., no gene orthologs respond to miconazole and clotrimazole in both datasets (Fig. 3D). In contrast, between the two S. cerevisiae datasets, the only shared azole, clotrimazole, shows a significantly similar response (Fig. 3B). We compared published work that examined the transcriptome responses of S. cerevisiae (Kuo et al., 2010) and C. neoformans (Florio et al., 2011) to FLC. We found that, while there was significant overlap in orthologous genes impacted in the two species, (p = 1.6 × 10−3), there were also considerable differences: 67% of the genes with an altered response in C. neoformans whose orthologs in S. cerevisiae did not exhibit significant change, (Table S7) (Kuo et al., 2010).

Using chemical-genetic signatures to identify capsule biosynthesis mutants

Studies in S. cerevisiae have shown that that the phenotypic signatures of gene deletions for genes that act in the same process or protein complex tend to be similar (Collins et al., 2007; Costanzo et al., 2010; Nichols et al., 2010; Parsons et al., 2004; Parsons et al., 2006). We reasoned that this property of could be used in a pathogen to identify candidates for new genes involved in virulence by simply testing gene deletions that displayed phenotypic profiles similar to those corresponding to known virulence factors.

C. neoformans harbors an inducible polysaccharide capsule that is unusual among fungi (Del Poeta, 2004; Doering, 2009; Haynes et al., 2011; Kumar et al., 2011; O’Meara and Alspaugh, 2012; O’Meara et al., 2010; Vecchiarelli et al., 2013). The principal polysaccharide component, glucuronylxylomannan (GXM), consists of repeating glycan unit that has α-1,3-linked mannose backbone with side chains of β-linked glucuronic acid and xylose (Kozel et al., 2003). Capsule production is critical for virulence and the ability of C. neoformans to evade detection and destruction by the host immune system (Vecchiarelli et al., 2013).

To identify candidates for genes involved in capsule formation and/or attachment, we organized our dataset using hierarchical clustering of growth phenotypes produced by compound exposure. We focused on two clusters, each containing a gene(s) previously implicated in capsule biosynthesis: PBX1 and CPL1 (Liu et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2007b) in one cluster (Fig. 4A) and CAP60 (Chang and Kwon-Chung, 1998) in a second cluster (Fig. 4B). The pbx1Δ/cpl1Δ cluster contains nine genes and the cap60Δ cluster seven. We quantified capsule accumulation after induction by computing the ratio of the diameter of the cell and capsule to the diameter of the cell alone (Fig. 4C, Fig. 4D). Wild-type cells exhibit high capsule production, pbx1Δ mutants display a partial defect (Liu et al., 2007a) and cpl1Δ and cap60Δ mutants are acapsular (Chang and Kwon-Chung, 1998; Liu et al., 2008). We found that seven of nine mutants in the pbx1Δ/cpl1Δ cluster exhibit a statistically significant capsule defect, as did four of the seven mutants in the cap60Δ cluster. In contrast, previous work from our laboratory found that approximately 1% of the original C. neoformans library shows a gross defect in capsule production (Liu et al., 2008).

Figure 4. Chemical-genetic profiling identifies genes involved in capsule biosynthesis.

A) Cluster containing the chemical signatures of the pbx1Δ and cpl1Δ mutants.

B) Cluster containing the chemical signatures of the cap60Δ mutants.

C) Images of individual cells grown in 10% Sabouraud’s broth to induce capsule. Representative cells are shown for mutants that exhibit a statistically significant phenotype. Scale bar represents 5 μm.

D) Quantification of capsule sizes from all mutants in pbx1Δ/cpl1Δ (purple labels) cluster or cap60Δ(green labels) cluster. 100 cells were measured for each strain, the error bars represents the standard deviation, and p-values were calculated using Student’s t-test.

E) Colony counts from colony forming units (cfu) extracted from mouse lungs following an inhalation infection. Three mice are shown for each datapoint; the error bars represent the standard deviation and p-values were calculated using Student’s t-test.

Previous work showed that pbx1Δ mutants produce polysaccharide capsule whose attachment to the cell wall is sensitive to sonication, a finding that we confirmed (Fig. 4C, D). We refer to the cell’s ability to retain GXM on the cell surface as “capsule maintenance.” Knockout mutants in cnag_01058 do not exhibit a basal capsule defect but lost nearly 40% of their capsule diameter following sonication. Cells deleted for the GCN5 gene, like pbx1Δ cells, show both decreased capsule levels and sonication-sensitive capsule. None of the mutants from the cap60Δ cluster produces a sonication-sensitive phenotype, suggesting that the pbx1Δ/cpl1Δ and cap60Δ clusters organize mutants that have distinct phenotypes. However, because several mutants do not produce visible capsule, the sonication test is insufficient to definitively measure capsule maintenance. We therefore analyzed how much glucoronoxylomannan (GXM), the major capsular polysaccharide (Doering, 2009), is secreted into the growth medium by blotting with α-GXM antibodies (Fig. S2A). We found that two mutants that produce little (gcn5Δ) or no (yap1Δ) visible capsule still shed GXM into the medium, suggesting that they cannot retain capsule on their cell surface. Indeed, we found that they shed more GXM than pbx1Δ cells. Four of nine mutants in the pbx1Δ/cpl1Δ cluster exhibit a maintenance defect, whereas none of the cap60Δ cluster mutants do. We also found that GXM produced by these cells can be taken up and added to the surface (“donated”) of an acapsular mutant using a standard GXM transfer assay (Kozel and Hermerath, 1984; Reese and Doering, 2003). Moreover, apparent capsule-defective mutants shed GXM (Fig. S2B, C) and can donate GXM from conditioned medium (Fig. S2C). Mutants that appear to not secrete GXM (pbx1Δ, cpl1Δ, and sgf73Δ) can donate it, but only if conditioned medium concentration is increased 10-fold (Fig. S2D). These data are consistent with a recently published study on the role of Pbx1 in capsule attachment and assembly (Kumar et al., 2014).

Since the capsule is a major virulence trait of C. neoformans, we tested whether knockout mutants that exhibited a capsule defect displayed a defect in the mammalian host, using a murine inhalation model. We infected mice with a mixture of differentially-tagged wild-type and mutant cells at a ratio of 1:1. At 10 days post infection (dpi), we sacrificed animals, harvested and homogenized lung tissue, then plated on the appropriate selective media for colony forming units (CFUs). All but one of the pbx1Δ/cpl1Δ cluster members were significantly underrepresented relative to wild-type; the exception was the cnag_01058Δ mutant, which is defective in capsule maintenance but not capsule biosynthesis (Fig. 4C, S4A). yap1Δ cells, which appear acapsular but secrete GXM, displayed a major defect in fitness in the host (Fig. 4E). Three of four cap60Δ cluster mutants also display a defect in accumulation of CFUs in host lungs (Fig. 4E).

Chemogenomics identifies the cell cycle as a target of the anti-fungal small molecule S8

We included a number of drug-like antifungal compounds in our screen in order to identify their targets (Table 1). Our use of C. neoformans chemogenomics to assist in the identification of a target of toremifene is described elsewhere (Butts et al., 2014). Here we investigate the thiazolidine-2,4-dione derivatives originally described for their activity against C. albicans biofilms (Kagan et al., 2013).

Our chemogenomic profiling data of the thiazolidine-2,4-dione derivative S8 revealed a striking outlier: a knockout mutant in the gene coding for a C. neoformans ortholog of the conserved cell cycle kinase Wee1, is relatively resistant (Fig. 5A). We observed resistance at multiple concentrations of S8 (Table S2). The related compound NA8, which contains a replacement of a sulfur atom with a carbon atom on the thiazolidinedione moiety (Fig. 5B), does not elicit the same resistance (Fig. S3A). The wee1Δ mutant is also resistant to S10 (Fig. S3B), which harbors a C10 alkyl chain instead of C8 but is otherwise identical to S8 (Fig. S3C).

Figure 5. C. neoformans Cdc25 is a target of S8 in vivo and in vitro.

A) Chemical-genetic data of the growth scores of each knockout mutant grown on S8 (y-axis). The mutant that exhibited the greatest resistance is wee1Δ. The mutant strain that showed the greatest sensitivity to S8 is cnag_04462Δ.

B) Structures of S8, NA8, and NSC 663284. The structure of S10 is shown in Fig. S3C.

C) G2/M regulation (Morgan, 2007).

D) DNA content of asynchronous C. neoformans culture split into aliquots for treatment with compounds of interest, with samples harvested at appropriate times. Data for DMSO-treated culture is shown.

E) DNA content from NA8-treated culture from same starting culture as Fig. 5F.

F) DNA content from S8-treated culture from same starting culture as Fig. 5F.

G) Phosphatase activity of purified C. neoformans Cdc25 catalytic domain (CNAG_01572, aa442–662).

H) Michaelis-Menten kinetics of S8 inhibition of CnCdc25 from in vitro phosphatase activity. A noncompetitive model of enzyme inhibition produced the best R2 value (0.94).

Wee1 regulates the G2/M cell cycle checkpoint through inhibitory phosphorylation of Cdk1, which in turn is required for cells to traverse the checkpoint. The essential phosphatase Cdc25 activates Cdk1 by removing the inhibitory phosphorylation added by Wee1 (Morgan, 2007) (Fig. 5C). Because the wee1Δ is relatively resistant to S8, we hypothesized that S8 targeted a protein that acts through Wee1 to regulate Cdk1. One such target could be Cdc25.

We reasoned that if the Wee1/Cdc25-regulated step of the cell cycle were an important target of S8 in vivo, wild-type C. neoformans cells treated with S8 would arrest at G2/M. To test this prediction, we treated exponential cultures with S8, S10, or NA8 and examined the impact on the cell cycle. We harvested and fixed representative samples every 30 minutes, then analyzed DNA content by flow cytometry. Control cultures treated with DMSO (carrier) (Fig. 5D) or the control compound NA8 (Fig. 5E) stayed asynchronous for the entire 3.5 hrs of the time course. Strikingly, S8-treated (Fig. 5F) cells accumulated with 2C DNA content, which indicates G2/M arrest in C. neoformans, a haploid yeast (Whelan and Kwon-Chung, 1986). At later timepoints, cells synthesize DNA but do not complete mitosis and cytokinesis. This is consistent with observations in S. pombe that partial inhibition of Cdk1 permits re-replication of DNA (Broek et al., 1991).

Because inhibition of Cdc25 would provide a parsimonious explanation for the genetic and biological properties of S8, we tested whether S8 inhibits C. neoformans Cdc25 in vitro. We expressed and purified the catalytic domain of a C. neoformans ortholog (CNAG_07942) in E. coli (Fig. S3D) and then performed in vitro phosphatase assays using 3-O-methyl fluorescein phosphate (OMFP) as a substrate (Fig. 5G, H) (Hill et al., 1968). We observed that S8 inhibits Cdc25 activity (Ki ~140μM, Fig. 5E), as do both S10 (Fig. S3E) and NSC 663284 (Ki~250μM, Fig. S3F), a commercially available inhibitor of mammalian Cdc25 (Pu et al., 2002). The control compound NA8 does not inhibit C. neoformans Cdc25 in vitro (Fig. S3G). For S8, the in vitro inhibition constant is roughly comparable to the liquid MIC value against C. neoformans, which we measured to be ~60μM in YNB. S10 has a higher Ki (Ki~310μM) but similar to the MIC value (~55μM) measured in YNB agar compared to S8.

O2M: a genetic biomarker algorithm to predict compound synergies

Drug resistance is a major clinical challenge in the treatment of both bacterial and fungal infections (Anderson, 2005; Cantas et al., 2013). An effective therapeutic strategy is to treat patients with drugs that act synergistically, enhancing each other’s effectiveness beyond that produced by the sum of each drug’s individual impact (Kalan and Wright, 2011). This approach is thought to decrease acquisition drug resistance, increase the available drug repertoire (Kalan and Wright, 2011) and ameliorate toxicities (Kathiravan et al., 2012; Lehar et al., 2009).

We hypothesized that we could use the chemogenomic information from our screens of drugs known to act synergistically, such as FLC and fenpropimorph (Jansen et al., 2009) to identify new synergistic interactions (Fig. 6A). When we compared the identity of genes whose knockouts “responded” to each individual small molecule in a known synergistic pair (|Z| ≥ 2.5, Table S3–S4), we found that this “responsive” gene set was significantly enriched over the expected value (Fisher’s exact test, p ≤ 6 × 10−5) (Fig. 6A, top). This observation is consistent with a previous report that the chemical-genetic response to each drug in a synergistic pair is enriched for overlapping genes (Jansen et al., 2009).

Figure 6. O2M approach for predicting compound synergy.

A) Approach for predicting compound synergistic interaction.

B) FICI values for fluconazole (FLC). Predicted synergistic compounds are labeled in purple and known synergistic compounds in green. Bars represent the average of two assays but both had to be FICI < 0.5 to be considered synergistic. Compounds labeled in blue are negative controls from one of two categories: 1) predicted to synergize with geldanamycin (GdA) but not FLC or 2) randomly generated list of compounds not predicted to be synergistic with either FLC or GdA. Yellow bars represent an FICI < 0.5 (synergistic) and blue bars and FICI ≥ 0.5 (not synergistic).

C) FICI values for GdA. Labels and colors are analogous to those in part B.

D) Contingency table of synergistic vs non-synergistic interactions with FLC. p < 0.0008 (Fisher’s exact test).

E) Contingency table of synergistic vs non-synergistic interactions with GdA. p < 0.0008 (Fisher’s exact test).

This overlap in responsive gene sets led us to consider the possibility that overlapping responsive genes from known synergistic compound pairs could be used as biomarkers to predict new synergistic combinations. Our method involves first identifying the overlaps in responsive gene sets for all compounds that had been reported in the literature to synergize with a small molecule of interest (“compound X”), selecting those genes common to all of those sets (Fig. 6A, middle – the overlaps of overlaps). We refer to these genes as “synergy biomarker genes.” Critically, we next hypothesized that any compound that contains one or more of these synergy biomarker genes in its responsive gene set would be synergistic with compound X. Because our method used the overlaps of response gene overlaps between compounds known to be synergistic, we refer to it as the “overlap-squared method” or “O2M.”

We then tested O2M using two drugs for which substantial literature synergy information was available: FLC and geldanamycin (GdA). FLC is an approved antifungal drug. GdA is an inhibitor of Hsp90, a chaperone protein with many physical and genetic interactions (Taipale et al., 2010). We performed our analysis on fenpropimorph and sertraline, which are known to act synergistically with FLC (Jansen et al., 2009; Zhai et al., 2012) and cyclosporine and rapamycin, which are known to act synergistically with GdA (Francis et al., 2006; Kumar et al., 2005). Using this prior knowledge and our data, we identified synergy biomarker genes for FLC (CNAG_00573, CNAG_03664, and CNAG_03917) and GdA (CNAG_01172, CNAG_03829, and CNAG_01862). We generated a list of compounds from our chemical-genetics dataset that contain one or more of these genes in their responsive genes set.

We then used a standard “checkerboard” assay to experimentally determine fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI), and we adopted the standard that an FICI value below 0.5 is synergistic (Meletiadis et al., 2010). We determined FICIs for FLC and GdA with three sets of compounds: 1) the compounds predicted from synergy biomarker genes, 2) the predicted synergistic compounds for the other drug (e.g. we tested compounds predicted to be synergistic with GdA for synergy with FLC), and 3) a randomly generated subset of the compounds not predicted to act synergistically with either FLC or GdA. The second and third groups are as controls for compounds that are generally synergistic and to determine the background frequency of synergistic interactions within a set of compounds.

Respective experimental FICI values for FLC and GdA are shown in Fig. 6B and 6C (yellow bars: synergy; blue bars additive or worse interactions). The labels for compounds we predicted to be synergistic are colored purple, positive controls (published synergistic compound pairs) are colored green, and predicted negative control compounds colored blue (Fig. 6). We observed that only ~10% of the negative control compounds act synergistically with either FLC or GdA. In striking contrast, we found ~80% and ~60% of the compounds selected by O2M are synergistic with FLC and GdA, respectively. Thus, for two unrelated compounds, O2M is highly successful at predicting synergistic interactions and performs vastly better than the brute force trial-and-error approach (Fig. 6D, E) (p < 0.0008, Fisher’s exact test).

Discussion

We applied chemogenomic profiling to the major fungal driver of AIDS-related death, the encapsulated yeast C. neoformans, to produce a chemical-genetic atlas of this important pathogen. Beyond identifying new virulence factors and compound mode-of-action, we describe a conceptually general approach to identifying drug synergies that combines prior knowledge and chemogenomic profiles to identify compound synergies.

A chemical-genetic atlas for Cryptococcus neoformans

We maximized the quality of the atlas in several ways. To capture concentration-dependent impacts of compounds, we obtained MIC for each compound and examined the genetic responses at multiple concentrations below MIC. In addition, we performed a large number of control screens and incorporated batch information for systematic correction. Overall benchmarks of data quality (Fig. 1) together with nearest neighbor and Gene Ontology analysis (Fig. 2) support the existence of substantial chemical-genetic signal in the data. Even genes with orthologs in both S. cerevisiae and C. neoformans show considerable differences in responses (Fig. 3). While this may not be surprising given the large phylogenetic distance between these fungi, it shows that understanding the chemical responses of pathogens requires pathogen-focused studies, even when considering conserved genes and processes. For example, we observed differences in the responses to azole drugs between S. cerevisiae and C. neoformans (Fig. 3). Since azoles are heavily used clinically, differences in responses between species are of significant interest.

Insights gained from initial use of the C. neoformans chemical-genetic atlas

Identification of mutants that impact capsule formation and mammalian infection

Our studies on capsule biosynthesis genes focused two different clusters that contained genes that we and others have shown to be required for capsule formation, the pbx1/cpl1Δ cluster and the cap60Δ cluster. As anticipated from model organism studies (Collins et al., 2007; Costanzo et al., 2010; Nichols et al., 2010; Parsons et al., 2004; Parsons et al., 2006), these clusters were indeed enriched for genes whose mutants are defective in capsule biosynthesis and mammalian pathogenesis. The genes represented by the two clusters differed functionally in that genes in the pbx1/cpl1Δ cluster but not the cap60Δ cluster are required for association of capsule polysaccharide with the cell surface (Fig. 4, S4). A recent study on Pbx1 and its ortholog, Pbx2, proposes that the two proteins act redundantly in capsule assembly (Kumar et al., 2014). pbx1Δ and pbx2Δ cells shed lower amounts of GXM into the culture medium but that the GXM functions in a capsule transfer assay. Electron microscopy studies indicate that these mutants exhibit defects in the cell wall. Our data are fully consistent with these data. Other genes from the pbx1Δ/cpl1Δ cluster likely play a role in these processes. Some, like GCN5 and SGF73, which encode orthologs of the yeast SAGA histone acetylase/deubiquitylase complex, are clearly regulatory, while others could act more directly. While detailed validation and investigation of these many candidates (including gene deletion reconstruction studies) will be required to obtain mechanistic insight into capsule biology, their enrichment suggests value of this Cryptococcal chemogenomic resource in identifying mutants defective in virulence.

Compound target identification

Chemogenomic profiling has proven useful in identifying targets of uncharacterized compounds (Parsons et al., 2006), including in the pathogenic fungus C. albicans (Jiang et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2009). Chemical-genetic data can be used to determine the target of compounds within complex mixtures (Jiang et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2009). Our goal differed: we sought to identify targets of repurposed compounds, as described elsewhere (Butts et al., 2013), or, in the case of S8, a compound identified as an inhibitor of Candida biofilms (Kagan et al., 2013). The identification of the Wee1 kinase as a sensitivity determinant for S8, the cell cycle arrest produced by S8, and the ability of the compound to inhibit CnCdc25 in vitro together support the model that S8 inhibits growth through via the cell cycle at least in part via inhibition of Cdc25. Whether this explains its impact on biofilms requires further investigation. As with any compound target, ultimate proof that Cdc25 is the target of S8 will require the isolation of resistance alleles of CDC25.

Given the simplicity of the pharmacophore and its Ki for CnCdc25, it would not be surprising if S8 had additional cellular targets, as recently described (Feldman et al., 2014). Cdc25 is a conserved cell cycle phosphatase and therefore might be considered a poor drug target a priori but cyclin-dependent kinases are a focus of recent anti-parasite therapeutics (Geyer et al., 2005). It is also notable that the target of azole antifungals, lanosterol 14-demethylase (Ghannoum and Rice, 1999) is conserved from yeast to human.

O2M: predicting compound synergies using prior knowledge and chemical profiles

Identifying synergistic drug interactions is of considerable clinical interest, but efficient methods for their identification are elusive. Systematic examination of combinations of a small set of compounds using S. cerevisiae suggests that synergies are relatively rare and often involve so-called “promiscuous” synergizers, compounds that are synergistic with multiple partners (Cokol et al., 2011). Chemogenomic studies have shown that drugs known to be synergistic tend to have overlapping “responding” gene sets (Jansen et al., 2009). We expanded on this concept to develop a highly parallel method, O2M, for efficiently predicting synergistic drug interactions. Our work utilizes prior knowledge of drug synergies to identify a discrete set of predictive biomarker genes for a given compound. We experimentally demonstrated the utility of O2M for two compounds, FLC and geldanamycin. Our method identified dozens of synergistic interactions and discovered a small number of biomarkers that could serve as readouts for further screens for synergistic drugs. The method appears to not simply select promiscuous synergiziers: five of six drugs previously classified as promiscuous synergizers (Cokol et al., 2011) were tested in our studies but most were not predicted to be synergistic by O2M. One of the promiscuous compounds was a positive control (fenpropimorph with FLC) and another (dyclonine) was predicted synergistic with FLC but was not and was predicted not synergistic with GdA but was. We anticipate that O2M could be used to identify synergistic compound interactions in published E. coli and C. albicans chemical-genetics datasets (Jiang et al., 2008; Nichols et al., 2010; Xu et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2009).

Experimental Procedures

Determination of MICs

We determined minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) on solid growth medium for each compound used in screening (Table 1).

Colony array-based chemogenomic profiling

C. neoformans knockouts were inoculated from frozen 384-well plates to YNB + 2% glucose. Plates were grown 24hrs at 30°C, then used to inoculate screening plates containing compounds of interest.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed as previously described (Baryshnikova et al., 2010) with the a few exceptions.

C. neoformans ortholog identification and GO term mapping

Mapping from S. cerevisiae Uniprot Proteins to C. neoformans Uniprot Proteins was done using One-to-one mappings in MetaPhOrs (http://metaphors.phylomedb.org/). C. neoformans ORFs were compared to a database of S. cerevisiae Uniprot Proteins using blastp (Altschul et al., 1997) with a E-score cutoff of 10−30. Corresponding yeast GO annotations were mapped onto the C. neoformans ORFs.

Comparison of transcriptional response to FLC

Compared transcriptional responses between S. cerevisiae (Kuo et al., 2010) and C. neoformans (Florio et al., 2011).

Capsule induction assay

Samples were grown overnight at 30°C in 100% Sabouraud’s broth, then diluted 1:100 into 10% Sabouraud’s broth buffered with 50mM HEPES pH 7.3 and grown for 3 days at 37°C. India ink was added at 3:1 ratio and samples imaged on a Zeiss Axiovert microscope.

Capsule transfer assay

Performed as in (Reese and Doering, 2003), with minor modifications.

GXM immunoblot assay

Conditioned medium was made from donor GXM donor strains as described above.

Mouse infection assay

Mouse lung infections were performed as previously described (Chun et al., 2011).

Cdc25 protein purification

We identified the C. neoformans ortholog of Cdc25, CNAG_01572, by best reciprocal BLAST (Altschul et al., 1997) hit with the human Cdc25A, Cdc25B, and Cdc25C protein isoforms. We then inserted the exonic sequence of the catalytic domain into a 6x-His tag expression vector for purification.

Cdc25 phosphatase assay

Cdc25 phosphatase activity was analyzed in activity buffer (50mM Tris pH 8.3, 5% glycerol, 0.8mM dithiolthreitol, and 1% PVA).

Cdc25 inhibitor treatment and FACS analysis

Wild-type C. neoformans was grown overnight in 1x YNB at 30°C with rotation. Cultures were diluted to OD600 ~ 0.2 into 150ml 1x YNB, then incubated 3hr at 30°C. Samples were then split and NA8, S8, and S10 added to 60μM. Equivalent volume of DMSO was added to the control culture.

Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Index (FICI) assay for synergy

We determined FICI using a standard checkerboard assay (Hsieh et al., 1993), calculating FICI as described using a 50% growth inhibition cutoff for MICs for individual compounds (Hsieh et al., 1993; Meletiadis et al., 2010), then using a standard cutoff of FICI < 0.5 to define synergy.

See Extended Experimental Procedures for additional details.

Supplementary Material

A) Pairwise correlation scores between the chemical genetic profiles of different compounds (grey) and the same compounds at different concentrations (purple) screened on same day (same batch). Pairwise correlation scores of similar value were binned together (x-axis) shown relative to the percentage of the total population (y-axis). Correlation scores between the chemical-genetic profiles of the same compounds are significantly higher than those between different compounds (Wilcoxon test, p = 5.3 × 10−69).

Table S1: List of strains used in this study, related to Figure 1.

Scores for each small molecule-gene knockout strain combination. Scores were generated as described in Experimental Procedures. Related to Fig. 1.

A) Blot against GXM from conditioned medium. Cells were grown for one week to produce conditioned medium.

B) Representative images from capsule transfer assay. Scale bar represents 5 8m.

C) Quantification of capsule transfer assay. 200 cells were counted for each experiment. Columns show the average of three experiments and error bars represent the standard deviation. Asterisk represents p-value of 0.007 or lower (Student’s t-test).

A: Chemical-genetic data of the growth scores of each knockout mutant grown on NA8 (y-axis). Unlike S8, wee18 did not exhibit significant resistance.

B: Chemical-genetic data of the growth scores of each knockout mutant grown on S10 (y-axis). As with S8, the mutant that exhibited the greatest resistance is wee18. C: S10 structure

C: Structure of S10.

D: Purified C. neoformans Cdc25 protein.

E: Michaelis-Menten kinetics of S10 inhibition of CnCdc25 from in vitro phosphatase activity. A noncompetitive (allosteric) model of enzyme inhibition produced the best R2 value (0.96). Grey box is shown in inset.

F: Michaelis-Menten kinetics of NSC 663284 inhibition of CnCdc25 from in vitro phosphatase activity. A noncompetitive (allosteric) model of enzyme inhibition produced the best R2 value (0.88).

G: Michaelis-Menten kinetics of CnCdc25 in vitro phosphatase activity NA8 inhibition of CnCdc25 from in vitro phosphatase activity. NA8 does not detectably inhibit CnCdc25.

List of small molecule sensitive phenotypes for each gene knockout. Significant sensitivities are shown for Z scores < −2.5 at two or more concentrations of a single small molecule unless only a single concentration was screened. Related to Fig. 1.

List of small molecule resistant phenotypes for each gene knockout. Significant resistances are shown for Z scores > +2.5 at two or more concentrations of a single small molecule unless only a single concentration was screened.

List of compounds and the genes whose knockouts exhibit sensitive or resistant phenotypes. Related to Figure 1.

List of compounds and the GO terms enriched among genes whose knockout mutants exhibit sensitive phenotypes. Related to Fig. 2.

Comparison of transcriptional response to FLC in S. cerevisiae (Kuo et al., 2010) and C. neoformans (Florio et al., 2011). Related to Fig. 3.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants 5R01AI099206 to H.D.M., 1R01AI091422 to D.J.K., 1R01HG005084 and 1R01GM04975 to C.L.M, and a grant from the CIFAR Genetic Networks Program to C.L.M.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

J.C.S.B. and H.D.M. designed the study. J.C.S.B. carried out all of experiments described in the paper. J.N. and C.L.M. performed data analysis shown in Figs. 1B–D, Fig. 2 and Fig. 3. B.V., R.D., and C.L.M. filtered, de-noised and scored the primary colony array data. A.B., S.K., I.P., and D.J.K. provided compounds and guidance. J.C.S.B. and H.D.M. wrote the manuscript with input from all co-authors.

Supplemental Material includes Extended Experimental Procedures, Literature References for Table 1, three supplementary figures and seven supplementary tables.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaeffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JB. Evolution of antifungal-drug resistance: mechanisms and pathogen fitness. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2005;3:547–556. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong-James D, Meintjes G, Brown GD. A neglected epidemic: fungal infections in HIV/AIDS. Trends Microbiol. 2014;22:120–127. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baryshnikova A, Costanzo M, Kim Y, Ding H, Koh J, Toufighi K, Youn JY, Ou J, San Luis BJ, Bandyopadhyay S, et al. Quantitative analysis of fitness and genetic interactions in yeast on a genome scale. Nat Meth. 2010;7:1017–1024. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broek D, Bartlett R, Crawford K, Nurse P. Involvement of p34cdc2 in establishing the dependency of S phase on mitosis. Nature. 1991;349:388–393. doi: 10.1038/349388a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butts A, DiDone L, Koselny K, Baxter BK, Chabrier-Rosello Y, Wellington M, Krysan DJ. A Repurposing Approach Identifies Off-Patent Drugs with Fungicidal Cryptococcal Activity, a Common Structural Chemotype, and Pharmacological Properties Relevant to the Treatment of Cryptococcosis. Eukaryot Cell. 2013;12:278–287. doi: 10.1128/EC.00314-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butts A, Koselny K, Chabrier-Roselló Y, Semighini CP, Brown JCS, Wang X, Annadurai S, DiDone L, Tabroff J, Childers WE, et al. Estrogen Receptor Antagonists Are Anti-Cryptococcal Agents That Directly Bind EF Hand Proteins and Synergize with Fluconazole In Vivo. mBio. 2014:5. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00765-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butts A, Krysan DJ. Antifungal Drug Discovery: Something Old and Something New. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002870. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantas L, Shah SQA, Cavaco LM, Manaia C, Walsh F, Popowska M, Garelick H, Bürgmann H, Sørum H. A brief multi-disciplinary review on antimicrobial resistance in medicine and its linkage to the global environmental microbiota. Front Microbiol. 2013;4:96. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang YC, Kwon-Chung KJ. Isolation of the Third Capsule-Associated Gene, CAP60, Required for Virulence in Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2230–2236. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2230-2236.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun CD, Brown JCS, Madhani HD. A Major Role for Capsule-Independent Phagocytosis-Inhibitory Mechanisms in Mammalian Infection by Cryptococcus neoformans. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;9:243–251. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cokol M, Chua HN, Tasan M, Mutlu B, Weinstein ZB, Suzuki Y, Nergiz ME, Costanzo M, Baryshnikova A, Giaever G, et al. Systematic exploration of synergistic drug pairs. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7:544. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins SR, Miller KM, Maas NL, Roguev A, Fillingham J, Chu CS, Schuldiner M, Gebbia M, Recht J, Shales M, et al. Functional dissection of protein complexes involved in yeast chromosome biology using a genetic interaction map. Nature. 2007;446:806–810. doi: 10.1038/nature05649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo M, Baryshnikova A, Bellay J, Kim Y, Spear ED, Sevier CS, Ding H, Koh JLY, Toufighi K, Mostafavi S, et al. The Genetic Landscape of a Cell. Science. 2010;327:425–431. doi: 10.1126/science.1180823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Poeta M. Role of phagocytosis in the virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot Cell. 2004;3:1067–1075. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.5.1067-1075.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittmar J, Reid R, Rothstein R. ScreenMill: A freely available software suite for growth measurement, analysis and visualization of high-throughput screen data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:353–363. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doering TL. How sweet it is! Cell wall biogenesis and polysaccharide capsule formation in Cryptococcus neoformans. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2009;63:223–247. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman M, Al-Quntar A, Polacheck I, Friedman M, Steinberg D. Therapeutic Potential of Thiazolidinedione-8 as an Antibiofilm Agent against Candida albicans. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández L, Hancock REW. Adaptive and Mutational Resistance: Role of Porins and Efflux Pumps in Drug Resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25:661–681. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00043-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florio A, Ferrari S, De Carolis E, Torelli R, Fadda G, Sanguinetti M, Sanglard D, Posteraro B. Genome-wide expression profiling of the response to short-term exposure to fluconazole in Cryptococcus neoformans serotype A. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:97. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis LK, Alsayed Y, Leleu X, Jia X, Singha UK, Anderson J, Timm M, Ngo H, Lu G, Huston A, et al. Combination Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Inhibitor Rapamycin and HSP90 Inhibitor 17-Allylamino-17-Demethoxygeldanamycin Has Synergistic Activity in Multiple Myeloma. Clinical Cancer Research. 2006;12:6826–6835. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer JA, Prigge ST, Waters NC. Targeting malaria with specific CDK inhibitors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1754:160–170. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2005.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghannoum MA, Rice LB. Antifungal agents: mode of action, mechanisms of resistance, and correlation of these mechanisms with bacterial resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:501–517. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.4.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes BC, Skowyra ML, Spencer SJ, Gish SR, Williams M, Held EP, Brent MR, Doering TL. Toward an integrated model of capsule regulation in Cryptococcus neoformans. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002411. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitman J, Kozel TR, Kwon-Chung KJ, Perfect JR, Casadevall A, editors. Cryptococcus: from human pathogen to model yeast. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hill HD, Summer GK, Waters MD. An automated fluorometric assay for alkaline phosphatase using 3-O-methylfluorescein phosphate. Analytical Biochemistry. 1968;24:9–17. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(68)90054-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillenmeyer ME, Fung E, Wildenhain J, Pierce SE, Hoon S, Lee W, Proctor M, St Onge RP, Tyers M, Koller D, et al. The Chemical Genomic Portrait of Yeast: Uncovering a Phenotype for All Genes. Science. 2008;320:362–365. doi: 10.1126/science.1150021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh MJ, Yu CM, Yu VL, Chow JW. Synergy assessed by checkerboard: a critical analysis. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 1993;16:343–349. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(93)90087-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janbon G, Ormerod KL, Paulet D, Byrnes EJ, III, Yadav V, Chatterjee G, Mullapudi N, Hon C-C, Billmyre RB, Brunel F, et al. Analysis of the Genome and Transcriptome of Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii Reveals Complex RNA Expression and Microevolution Leading to Virulence Attenuation. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen G, Lee AY, Epp E, Fredette A, Surprenant J, Harcus D, Scott M, Tan E, Nishimura T, Whiteway M, et al. Chemogenomic profiling predicts antifungal synergies. Mol Syst Biol. 2009:5. doi: 10.1038/msb.2009.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang B, Xu D, Allocco J, Parish C, Davison J, Veillette K, Sillaots S, Hu W, Rodriguez-Suarez R, Trosok S, et al. PAP Inhibitor with In Vivo Efficacy Identified by Candida albicans Genetic Profiling of Natural Products. Chem Biol. 2008;15:363–374. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan S, Jabbour A, Sionov E, Alquntar AA, Steinberg D, Srebnik M, Nir-Paz R, Weiss A, Polacheck I. Anti-Candida albicans biofilm effect of novel heterocyclic compounds. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013:68. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalan L, Wright GD. Antibiotic adjuvants: multicomponent anti-infective strategies. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2011;13:null–null. doi: 10.1017/S1462399410001766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kathiravan MK, Salake AB, Chothe AS, Dudhe PB, Watode RP, Mukta MS, Gadhwe S. The biology and chemistry of antifungal agents: A review. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 2012;20:5678–5698. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozel TR, Hermerath CA. Binding of cryptococcal polysaccharide to Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 1984;43:879–886. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.3.879-886.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozel TR, Levitz SM, Dromer F, Gates MA, Thorkildson P, Janbon G. Antigenic and Biological Characteristics of Mutant Strains of Cryptococcus neoformans Lacking Capsular O Acetylation or Xylosyl Side Chains. Infect Immun. 2003;71:2868–2875. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.5.2868-2875.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P, Heiss C, Santiago-Tirado FH, Black I, Azadi P, Doering TL. Pbx proteins in Cryptococcus neoformans cell wall remodeling and capsule assembly. Eukaryot Cell. 2014 doi: 10.1128/EC.00290-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P, Yang M, Haynes BC, Skowyra ML, Doering TL. Emerging themes in cryptococcal capsule synthesis. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 2011;21:597–602. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Musiyenko A, Barik S. Plasmodium falciparum calcineurin and its association with heat shock protein 90: mechanisms for the antimalarial activity of cyclosporin A and synergism with geldanamycin. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2005;141:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo D, Tan K, Zinman G, Ravasi T, Bar-Joseph Z, Ideker T. Evolutionary divergence in the fungal response to fluconazole revealed by soft clustering. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R77. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-7-r77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehar J, Krueger AS, Avery W, Heilbut AM, Johansen LM, Price ER, Rickles RJ, Short GF, III, Staunton JE, Jin X, et al. Synergistic drug combinations tend to improve therapeutically relevant selectivity. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:659–666. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Apodaca J, Davis LE, Rao H. Proteasome inhibition in wild-type yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells. Biotechniques. 2007a;42:158–162. doi: 10.2144/000112389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu OW, Chun CD, Chow ED, Chen C, Madhani HD, Noble SM. Systematic Genetic Analysis of Virulence in the Human Fungal Pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Cell. 2008;135:174–188. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu OW, Kelly MJS, Chow ED, Madhani HD. Parallel β-Helix Proteins Required for Accurate Capsule Polysaccharide Synthesis and Virulence in the Yeast Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot Cell. 2007b;6:630–640. doi: 10.1128/EC.00398-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loyse A, Bicanic T, Jarvis JN. Combination Antifungal Therapy for Cryptococcal Meningitis. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2522–2523. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1305981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Adair T, Aggarwal R, Ahn SY, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2095–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 7. Philidelphia: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Meletiadis J, Pournaras S, Roilides E, Walsh TJ. Defining fractional inhibitory concentration idex cutoffs for additive interactions based on self-drug additive combinations, Monte Carlo simulation analysis, and in vitro-in vivo correlation data for antifungal drug combinations against Aspergillus fumigatus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:602–609. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00999-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]