Abstract

We present a new transcriptome assembly of the Pacific whiteleg shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei), the species most farmed for human consumption. Its functional annotation, a substantial improvement over previous ones, is provided freely. RNA-Seq with Illumina HiSeq technology was used to analyze samples extracted from shrimp abdominal muscle, hepatopancreas, gills and pleopods. We used the Trinity and Trinotate software suites for transcriptome assembly and annotation, respectively. The quality of this assembly and the affiliated targeted homology searches greatly enrich the curated transcripts currently available in public databases for this species. Comparison with the model arthropod Daphnia allows some insights into defining characteristics of decapod crustaceans. This large-scale gene discovery gives the broadest depth yet to the annotated transcriptome of this important species and should be of value to ongoing genomics and immunogenetic resistance studies in this shrimp of paramount global economic importance.

Litopenaeus vannamei is a prawn native to the eastern Pacific Ocean from Sonoran Mexico to northern Peru where it has long been caught by inshore fisherman and offshore trawlers. Commonly called both the whiteleg shrimp and Pacific white shrimp, this species was first aquacultured in Florida in 1973 using a mated individual from Panama. By the early 1980's it was being cultured in Hawaii, the contiguous United States, Central and South America, and its mariculture spread to Asia in the 2000's1. It is now the dominant crustacean species grown in aquaculture worldwide, its use having surpassed that of the giant tiger prawn Penaeus monodon2. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization lists global production of this species growing from 146,382 tons in 2000 to 2,721,929 tons (>$11 billion US) in 2010, making the production of this species one of the fastest growing global food crops.

L. vannamei's dominant role in shellfish aquaculture has generated demand for genetic tools in this species that can be applied to nutrition, reproduction, development, and resistance to infectious disease. There have been several RNA-Seq and transcriptome reports for L. vannamei, including next-generation sequencing datasets3, studies of transcriptomic response to pollutant exposure4, different tissues5, and infection6,7,8,9,10,11. However, this report is the most extensive gene discovery work in the species to date and the first to make extensive functional annotation publicly available to the scientific community.

In this study, we used Illumina Hiseq for RNA-Seq experiments in hepatopancreas, gill, pleopod and abdominal muscle of one male shrimp to produce a robust pooled transcriptome assembly for L. vannamei using the Trinity software package. The output contigs were then functionally annotated employing Trinotate. These RNA-Seq reads have been availed to the public via these BioSample accessions: SAMN02918336, SAMN02918337, SAMN02918338, SAMN02918339 at NCBI, and our results are available at: http://repository.tamu.edu/handle/1969.1/152151. We demonstrate the utility of this resource with verification of immune transcripts, identification of novel shrimp genes, and metabolic pathway analysis.

Results

High quality de novo assembly of L. vannamei transcriptome

A total of 400,228,040 Illuimina HiSeq reads from hepatopancreas, gill, pleopod and abdominal muscle tissues were generated. After trimming the adapters, 399,056,712 (Table 1) reads were assembled with Trinity resulting in 110,474 contigs (Supplemental Data 1) with an N50 of 2,701 bases (Table 2). The HiSeq platform, the diversity of tissues sampled and the highly efficient Trinity pipeline allowed this significant improvement over recent transcriptomics efforts yielding only N50 values < 10003,4,6.

Table 1. RNA-Seq reads before and after adapter filtering.

| Gill | Hepatopancreas | Pleopods | Tail Muscle | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reads - Before Trimming Adapters | 111,119,234 | 59,419,932 | 122,556,454 | 107,132,420 | 400,228,040 |

| Reads - After Trimming Adapters | 110,846,074 | 59,190,538 | 122,146,844 | 106,873,256 | 399,056,712 |

| Yield (Gb) | 11.112 | 5.942 | 12.256 | 10.713 | 40.023 |

Table 2. Summary statistics of L. vannamei transcriptome assembly.

| Trinity Outputs | |

|---|---|

| Total trinity ‘genes’ | 87,307 |

| Total trinity transcripts | 110,474 |

| Percent GC | 44.12 |

| Longest contig (b) | 31,344 |

| Shortest contig (b) | 201 |

| Greater than 10 Kb | 595 |

| Greater than 5 K | 4,281 |

| Greater than 2 K | 17,726 |

| Transcrip contig N10 | 8,571 |

| Transcrip contig N20 | 6,003 |

| Transcrip contig N30 | 4,551 |

| Transcrip contig N40 | 3,542 |

| Transcrip contig N50 | 2,701 |

| Median contig length | 429 |

| Average contig | 1137.44 |

| Total assembled bases | 125,657,935 |

Functional annotation of shrimp transcriptome

Following the transcriptome assembly, we annotated the contigs by the Trinotate pipeline. The Trinotate software suite automates the functional annotation of the transcriptome.

Our annotation report from the Trinotate pipeline is presented as a document with the following column headers: 1) gene_id, 2) transcript_id, 3) Top_BLASTX_hit, 4) RNAMMER, 5) prot_id, 6) prot_coords, 7) Top_BLASTP_hit, 8) Pfam, 9) SignalP, 10) TmHMM, 11) eggNOG, 12) gene_ontology, and 13) prot_seq. The first two columns are: “gene_id” and “transcript_id”, representing predicted genes and their corresponding transcripts, respectively. The columns “Top_BLASTX_hit” and “Top_BLASTP_hit” show the top BlastX and BlastP hit results of homology searches against the NCBI database. BlastX is one of the latest additions to the Trinotate annotation pipeline and compares all six open reading frames (ORF) of the query sequences against the protein database. The RNAMMER column shows information about predicted ribosomal RNA genes discovered in the transcriptome assembly that were predicted by hidden Markov models (HMM). The prot_id, prot_coords and prot_seq columns provide the ID, location and translation of the longest ORFs, respectively. The Pfam column represents the HMMER/PFAM protein domain identification search results. HMMER is used to search databases for homologs of proteins, employing hidden Markov models. The SignalP column shows the presence and location of predicted signal peptides. Similarly, the TmHMM column presents the predicted transmembrane regions. The eggNOG (Evolutionary genealogy of genes: Non-supervised Orthologous Groups) column has the search result of the database of orthologous groups of genes, which are further annotated with functional description lines. Lastly, the gene_ontology column shows the relationship of these shrimp data to the Gene Ontology (GO) terms that aim to unify the representation of genes and gene products across all species.

Using the Trinotate pipeline, a total of 165,922 annotations were determined for our Trinity assembled contigs. We have designated the last eleven columns of Trinotate output detailed above (Top_BlastX_hit through prot-seq) as Annotation Holding Output Columns (AHOC). Considering that more than 165 K annotations for our contigs are too numerous for careful examination, we have created the following three filters: Filter A selects rows that have at least 10 AHOC, Filter B selects rows that have at least 9 AHOC, and Filter C selects rows that have at least 8 AHOC. Applying these filters to our data, Filter A results in selecting 590 gene IDs, Filter B 4,843 gene IDs, and finally Filter C 21,323 gene IDs. This method ensures that predicted genes/transcripts with maximum annotation information can be selected for targeted manual curating. Supplemental Data 2 represents the results of these filtrations graphically, and the filtered datasets are available in Supplemental Data 3.

In comparing these shrimp translated transcriptome contigs to those of other animals we were also curious as to know what proteins in NCBI's non-redundant database and from which species were most highly represented in BlastX hits of these assembled contigs (Supplemental Data 4). Drosophila myosin had the most (107) hits, and Drosophila proteins dominated these BlastX results. Many of the proteins with high hits could be considered “housekeeping” gene products, but some tissue-specific proteins were in the top twenty, such as Downs syndrome cell adhesion molecule (Dscam)12. Dscam receptors are diversified through mutually exclusive alternative exon splicing13, have roles in self-recognition in immunity and neural development14, and have been characterized in this species of shrimp15 as well as other crustaceans16.

Immune gene survey

To test the depth and accuracy of this annotated transcriptome, we searched in our dataset for the immune-related transcripts discovered by Sookruksawong et al.9. These transcripts were particularly interesting to us because they were representing differentially expressed immune-related genes between shrimp lines resistant and susceptible to Taura syndrome virus (TSV) and may also represent genes important in shrimp resistance to current scourges such as early mortality syndrome (EMS), also known as acute hepatopancreatic necrosis syndrome (AHPNS)17.

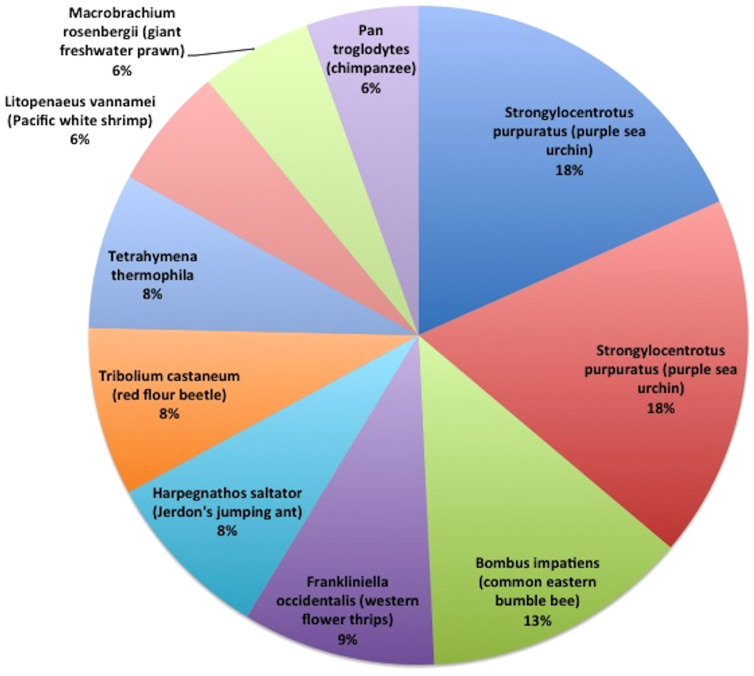

We used BlastX to find similarity between our 110,474 contigs as queries and the proteins identified in the TSV transcriptomic study9. There were 4,493 hits with an e-value < 1E-4 among our 110,474 contigs, and 3,088 hits with an e-value < 1E-10. In our subsequent analysis, we used the 3,088 hits resulting from this more restrictive (<1E-10) e-value filtering. Supplemental Data 5 shows the complete list of these proteins with additional information for each protein. In the first post-processing, we selected the top 50 BlastX hits with the more stringent e-value filtering and completed their annotation information by adding corresponding NCBI information to their records. Additionally, we selected the most frequently appearing (>40 hits) of these previously identified immune related proteins among our top BlastX hits and showed their representation as a pie chart. Figure 1 shows these proportions among our 3,088 BlastX results for all contigs. The highest three hits are zinc-finger 658b-like and serine/threonine phosphatase ankyrin repeat-like both from the purple sea urchin Strongylocentrus purpatus and zinc-finger BTB domain from the bee Bombus impatiens. This initial comparison survey will springboard studies of other immune gene families18,19.

Figure 1. Immune gene relative representation.

Of immune genes previously identified in resistance to Taura virus in L. vannamei, these twenty had the most hits from the transcriptome described here. Others outside of the top 20 accounted for the remaining 22% of hits.

Arthropod conservation and new decapod crustacean genes

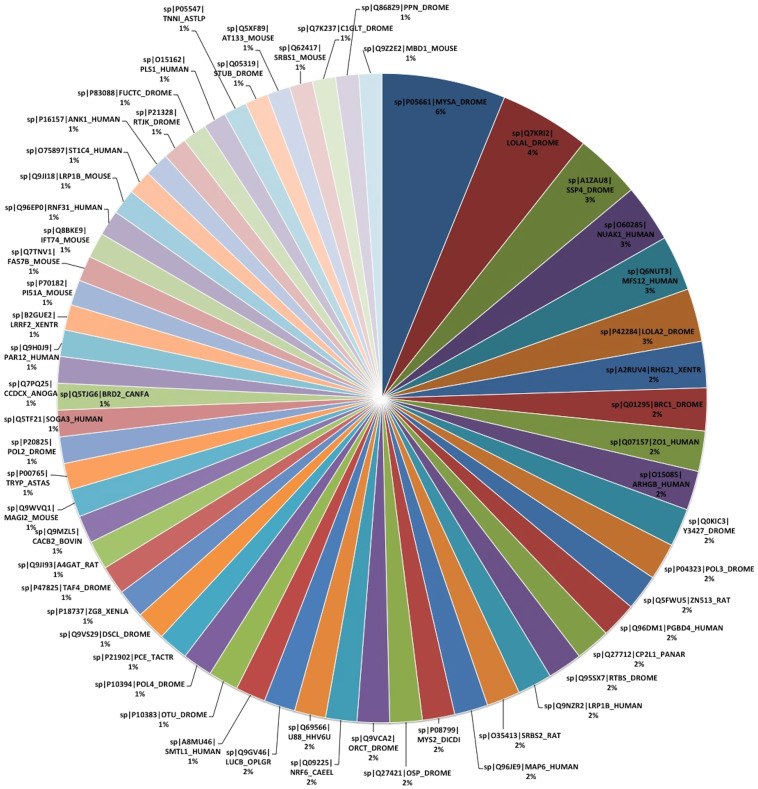

We also categorized the BlastX results to understand the distribution and frequency of the species that appear in the homology search between our contigs and the NCBI database. Figure 2 depicts all of the hits that had at least twenty BlastX hits and their frequency of appearing. Drosophila melanogaster is greatly represented (20 of the 59 top BlastX hits) as the model arthropod that has received most intensive study for decades and we suspect has the best coverage in the bioinformatic databases of tissue and developmental stage specific expression of any arthropod. Well-studied mammals are interspersed with invertebrate hits (13 human, 8 mouse, 3 rat, 3 Xenopus, and 1 zebrafish in the top 59 that hit 20 or more times).

Figure 2. Species percentages in BLASTX hits.

Sorting BLASTX results against our contigs, these 59 database hits appeared most frequently. These proteins were hit from 20 to 107 times.

Furthermore, we used BLAST to search similarities between our Trinity assembled contigs and the Daphnia pulex genome. The Joint Genome Institute annotation of v1.0 “Frozen Gene Catalog” was employed, which has all manual curations, as well as automatically annotated models chosen from the FilteredModels v1.1 set. In the first search, we used the BlastN tool to search for sequence similarities between our contigs and the D. pulex transcripts and CDs. We found 5,668 contigs with blast hits that had e-values < 1E-4, and 2,610 with hits scores as e-value < 1E-10 (Table 3). Table 4 shows the BlastN search results of the contigs against the D. pulex transcripts and CDs, for the latter case. The results are sorted by the most abundant hits, representing the top twenty genes, which had annotation information available at wFleaDatabase. It provides the gene IDs assigned by wFleaDatabase, as well as NCBI IDs. The complete 960 hits are available as Supplemental Data 6.

Table 3. Blast of L. vannamei contigs against D. pulex.

| Lowest E-value < 1E-4 | Lowest E-value < 1E-10 | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of contigs with protein hits | 30,534 | 26,224 |

| Number of contigs with transcript/CDS hits | 5,668 | 2,610 |

Table 4. Top BlastN search results for Trinity assembled contigs against D. pulex transcripts and CDS database.

In order to find the proteins corresponding to our contigs, we employed BlastX to examine all six frames. The D. pulex protein database was used. The BlastX search resulted in 30,534 hits with e-value < 1E-4 and 26,224 hits with e-value < 1E-10. The results are represented in Table 5 for the twenty most frequents BlastX hits, with e-value < 1E-10. For each entry, the corresponding UniProt link is provided for inquiring further information.

Table 5. Top BlastX search results for Trinity assembled contigs against D. pulex protein database.

| Total Appearance | Accession | UniProt Link | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 113 | jgi|Dappu1|313136|NCBI_GNO_0800085 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/E9G2Y1 |

| 2 | 87 | jgi|Dappu1|190169|estExt_Genewise1Plus.C_10589 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/E9FR09 |

| 3 | 75 | jgi|Dappu1|49585|e_gw1.19.281.1 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/E9GEX0 |

| 4 | 72 | jgi|Dappu1|30981|gw1.291.11.1 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/E9HUJ3 |

| 5 | 70 | jgi|Dappu1|232498|SNAP_00000556 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/E9FR26 |

| 6 | 64 | jgi|Dappu1|305108|PASA_GEN_3300053 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/E9GNX9 |

| 7 | 63 | jgi|Dappu1|307561|PASA_GEN_6500041 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/E9H319 |

| 8 | 60 | jgi|Dappu1|260966|SNAP_00029024 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/E9HK86 |

| 9 | 55 | jgi|Dappu1|61826|e_gw1.107.25.1 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/E9HEH7 |

| 10 | 54 | jgi|Dappu1|308707|PASA_GEN_8300084 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/E9H8T0 |

| 11 | 53 | jgi|Dappu1|330675|NCBI_GNO_14500072 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/E9HKB3 |

| 12 | 50 | jgi|Dappu1|233798|SNAP_00001856 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/E9FVR9 |

| 13 | 49 | jgi|Dappu1|197424|estExt_Genewise1Plus.C_290215 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/E9GLU7 |

| 14 | 49 | jgi|Dappu1|213970est|Ext_Genewise1.C_460168 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/E9GLU7 |

| 15 | 49 | jgi|Dappu1|327214|NCBI_GNO_8800026 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/E9HA35 |

| 16 | 47 | jgi|Dappu1|228567|estExt_fgenesh1_pg.C_1090053 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/E9HEW2 |

| 17 | 47 | jgi|Dappu1|304667|PASA_GEN_0300133 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/E9FVJ5 |

| 18 | 43 | jgi|Dappu1|232691|SNAP_00000749 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/E9FRF0 |

| 19 | 42 | jgi|Dappu1|190748|estExt_Genewise1Plus.C_20519 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/E9FTM1 |

| 20 | 42 | jgi|Dappu1|20391|gw1.30.80.1 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/E9GM72 |

KEGG and GO pathway analyses

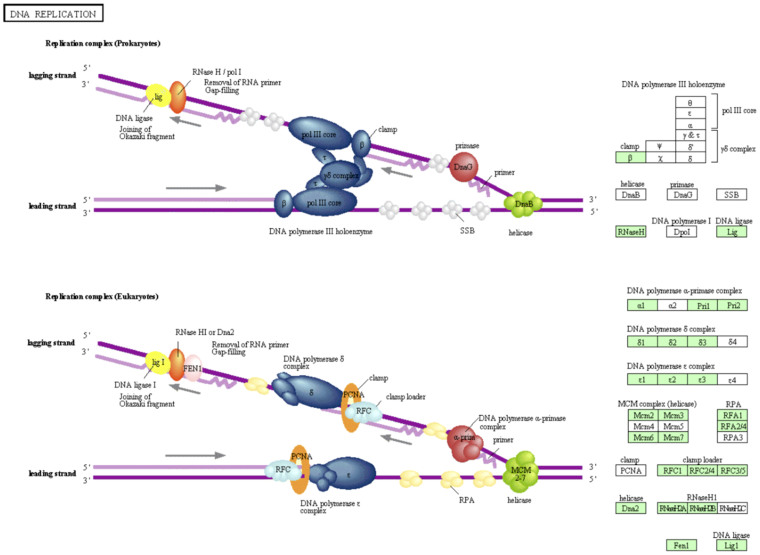

We also analyzed our contigs with the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway database20. Figure 3 shows an example of this analysis denoting the transcripts identified by our study involved in DNA replication. The protein products of several of these transcripts are required for White Spot Syndrome Virus (WSSV) replication21 and offer potential targets for interference with the pathogen's replication cycle22. An additional 337 pathways with shrimp orthologs represented in our transcriptome highlighted are available from the authors.

Figure 3. DNA replication pathway in L. vannamei.

KEGG pathway analysis20 shows orthologs in shrimp involved in DNA replication, as indicated by green highlighting. This is one example of hundreds of such pathway analyses available in Supplemental Data 5.

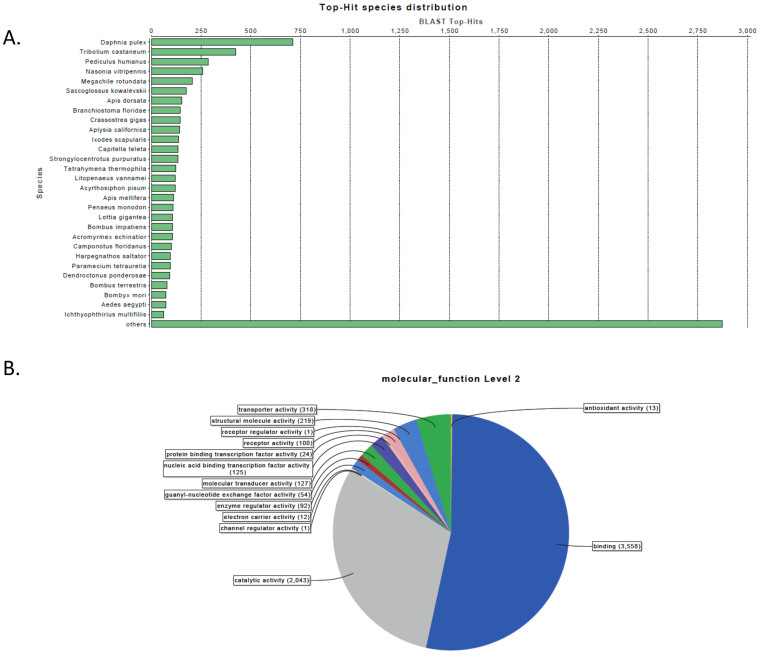

BLAST2GO (Figure 4) identified D. pulex as the top-hit species to this L. vannamei transcriptome by Blast analysis, followed by Tribolium castaneum and in third place Pediculus humanus. Chen et al6 identified the latter species as the one with most Blast hits of the White Spot Syndrome response transcriptome. Our comparison seems more consistent with the evolutionary relationship between Daphnia and Penaeid crustaceans.

Figure 4. BLAST2GO identifies D. pulex homologues and gene ontology profile.

(A) Protein BLAST top hit species distribution for the shrimp transcriptome. For identifying homologous proteins, the transcriptome shrimp proteins were BLASTed (BLASTP) against the non-redundant (nr) database using the Blast2GO package. The E-value cut-off was set at 1.0E−3. (B) Distribution of Gene Ontology terms related to Molecular function at level 2 for the shrimp transcriptome. Supported by Blast2GO trascriptome proteins were functionally mapped to GO terms and annotated by setting the following parameters: E-Value-Hit-Filter: 1.0E−3; Annotation cut-off: 55; GO weight: 5; Hsp-Hit Coverage cut-off: 0.

At the level of molecular function, binding molecules were found to be most abundant among the transcriptome (53%) followed by proteins with catalytic activity (28%). Antioxidant responses are invoked as a key component of the shrimp immune response, and in this reference transcriptome appeared in less than one percent of the transcripts. However, it is known that they are more abundant upon an immune challenge6.

Discussion

Invertebrate shrimp do not have a classical adaptive immune system based upon antibodies, T cells and specific memory of antigen23,24. Although our definitions of immunity beyond the jawed vertebrates are shifting25, there is so far only a consensus of evidence of the more ancient innate system in shrimp26. Thus, we cannot vaccinate shrimp for protection against WSSV or EMS27, making understanding of the total expressed transcriptome, genetic variability in the innate immune genes and regulatory regions of this invertebrate species all the more important. This improved transcriptome for L. vannamei is a step towards that goal.

L. vannamei is the most farmed of many important decapod crustacean food species including other shrimp and prawns, crayfish, lobster and crabs. Intensive aquaculture methods continue to improve as the global demand for shellfish increases. Thus, the application of this work in the whiteleg shrimp transcriptome will be applied back into the production organism in the aquaculture facility, and will pave the way for similar immunogenomic enhancement in other species28. For example the congener Litopenaeus setiferus of the northwest Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico is sometimes still cultured and is also susceptible to white spot syndrome virus, findings in L. vannamei will likely be readily adaptable to this sister species29,30. On even broader aquaculture industry supply and biosphere “One Health” levels, the improvements to this decapod crustacean transcriptome (and eventually other –omics) could have relevance for studies of krill. These small shrimp-like crustaceans are increasingly harvested for fish-meal and are often cited as the keystone species of the polar ecosystems31. They are threatened by climate change, and krill decline due to diatom losses in 1998 were linked to plummeting shearwater populations and the lack of that year's salmon spawn32.

Also of note is the potential ability this robust transcriptome affords in addressing the question of what it is that makes decapod crustaceans unique. Our comparison of the L. vannamei transcriptome to D. pulex also reveals the decapod shrimp transcripts that do not match any transcript from the branchiopod Daphnia. Besides the importance of these animals to fisheries, the order Decapoda provides crucial scavenging of aquatic ecosystems. Comparative transcriptomics can now address the developmental genetics that have allowed these crustaceans to diversify and dominate this ecological niche. In addition, this shrimp transcriptome can in turn serve as a point of genetic contrast for other more derived groups such as Brachyuran crabs that may have undergone carcinisation several independent times during their natural history by tagmosis of segments, anterial-posterial compression and ventral fusion of the abdomen33.

Several lines of inquiry have suggested that arthropods are capable of mounting specific immune responses subsequent to immune priming34,35,36,37,38. The gene that has drawn the most attention for possibly conferring adaptive immune capabilities in these invertebrates is DSCAM. Shrimp DSCAM employs alternative splicing to greatly diversify the expressed DSCAM repertoire, using many more possible introns for the diverse portion of the third immunoglobulin domain (79 in L. vannamei and P. monodon, versus 48 in D. melanogaster, 24 in Daphnia magna and 39 in Eriocheir sinensis)39. DSCAM transcripts with diverse immunoglobulin domains, transmembrane regions, and cytoplasmic tails are represented in the transcriptome described here (e.g. comp873 and comp34255, Supplemental Data 1).

Germane to analyses of taxa specific genes and particularly immune related genes are the assembly of transcripts encoded by multigene families employing only short NGS data de novo without a genome. The lack of introns is problematic for the more difficult to resolve multigene families. For example, a newly birthed retrogene lacking an intron could be incorrectly assembled with its progenitor gene using our NGS dataset, a confusion that would be easily avoided with genomic data. This is both a cautionary warning against over-extrapolating these data and also mandates genomic tools in this species.

With a genome of 2.5 gigabases spread over 44 pairs of chromosomes40, genomic resources for L. vannamei are still lacking. This annotated transcriptome should help to accelerate functional genomics in this species and perhaps other commercially and environmentally important decapod crustaceans while full genome sequencing projects are in progress. As food produced from global aquaculture now exceeds beef globally, shrimp is primed to play a major role in the “blue revolution” if the genetics of nutrition, growth and immunity can quickly catch up to the decades of study species such as cattle and poultry have enjoyed41.

Methods

Shrimp

Total RNA was prepared from one male Pacific white leg shrimp (L. vannamei) collected near Bahia Kino, Sonora, Mexico. Four tissues were targeted for distinct RNA-Seq experiments: hepatopancreas, gills, abdominal (tail) muscle, and pleopods. These four tissues allow transcriptomic profiling of cells engaged in many physiological processes in this arthropod including production of digestive enzymes, absorption of food, respiration, long-sarcomere muscle contraction (unique to invertebrates), mucosal immunity and reproduction.

RNA isolation and Illumina sequencing

Total RNA was prepared from the four tissues using Trizol Reagent (Life Technologies) per the manufacturer's instructions. From total RNA, mRNA was purified using magnetic oligo(dT) beads, then fragmented using divalent cations under elevated temperature. cDNA was synthesized from the fragmented mRNA using Superscript II (Invitrogen), followed by second strand synthesis. cDNA fragment ends were repaired and phosphorylated using Klenow, T4 DNA Polymerase and T4 Polynucleotide Kinase. Next, an adenosine was added to the 3′ end of the blunted fragments, followed by ligation of Illumina adapters via T-A mediated ligation. The ligated products were size selected by AMPure XP Beads and then PCR amplified using Illumina primers. The library creation, quality determination using an Agilent Bioanalyzer, and analysis were performed by Ambry Genomics. The Illumina HiSeq2000 was employed for sequence analysis. The libraries were seeded onto the flowcell at 9pM per lane yielding approximately 745 K pass-filter clusters per mm2 tile area. The libraries were sequenced using 116 + 10 + 101 cycles of chemistry and imaging.

Data preprocessing

Initial data processing and base calling, including extraction of cluster intensities, was done using RTA 1.13.48 (HiSeq Control Software 1.5.15). Sequence quality filtering script was executed in the Illumina CASAVA software (version 1.8.2, Illumina, Hayward, CA). Data yield (in Mbases), percent pass-filter (%PF), number of reads, percent raw clusters per lane, and quality (%Q30) was examined in Demultiplex_Stats.htm files. Other quality metrics were assessed in All.htm and IVC.htm including IVC plots and visualizations of cluster intensity over the duration of the sequencing run. The percentage of Q30 bases that passed filtering was above 77 for all lanes of the Illumina HiSeq flowcell.

Transcriptome assembly

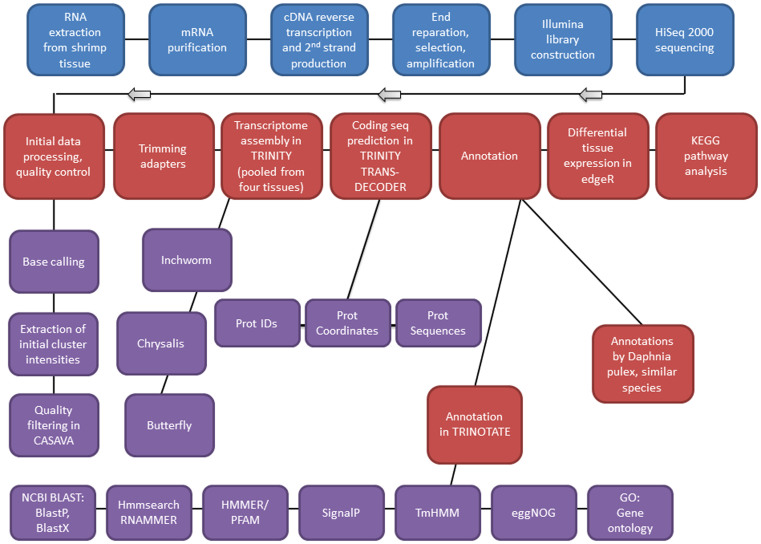

De novo assembly of the L. vannamei transcriptome was performed from the RNA-Seq data from the four pooled tissues with the trimming off adaptor sequences. The February 25, 2013 release of Trinity was used for assembly, Trinity Trans-decoder for coding sequence prediction, and Trinotate for functional annotation. The overall workflow is summarized graphically in Figure 5, and the transcriptome assembly in more detail in the next paragraph.

Figure 5. Overview of workflow.

Schematic flowchart shows the molecular biology and bioinformatic methods and software employed in this study. Blue steps are wet-lab procedures, red and purple steps are in silico.

After initial quality control steps, any reads that had adapter sequences attached to them were discarded. For adapter trimming the Cutadapt software was used42. The adapter-free reads were used for transcriptome assembly using the Trinity software43. Trinity is a de novo algorithm developed specifically for reconstructing the transcriptome, using de Bruijn graphs. Transcriptome assembly is challenging mainly because RNA-Seq data coverage levels are not evenly distributed. Furthermore, alternative splicing complicates assembly from individual genes. The goal of the Trinity package is to deliver one graph per expressed gene. Trinity consists of three parts: 1) Inchworm, 2) Chrysalis, and 3) Butterfly. During these three steps, Trinity makes linear contigs from RNA-Seq reads, generates and expands de Bruijn graphs, and finally outputs the transcripts and isoforms. The process starts by decomposing the reads into small overlapping pieces called Kmers and extending them by coverage. Finding the common sections of the intermediate transcripts determines alternative splicing, and those transcripts are re-grouped. The de Bruijn graphs are generated by integration of isoforms that are similar except one base. And finally, by finding and expanding the common section of transcripts and representing the most compact path on the graph, Trinity delivers the fully assembled transcriptome. The outputs are saved in a FASTA format, which includes all the transcripts. These can be accessed here: http://repository.tamu.edu/handle/1969.1/152151.

KEGG pathway and gene ontology analysis

The KEGG Automatic Annotation Server (KAAS, http://www.genome.jp/kaas-bin/kaas_main?mode=est_b) was employed to map KEGG pathways of assigned shrimp orthologs20. KEGG orthology (KO) assignments were performed based on the bi-directional best hit (BHH) of BLAST44. Functional annotation of the gene ontology (GO) terms was done using the BLAST2GO program (http://www.BLAST2GO.org/)45.

Author Contributions

N.G., L.B., E.R., J.A.S., C.D.J., S.V.D., R.R.S. and M.F.C. designed the project. A.A.L., J.S.C., R.R.S. and M.F.C. collected specimens and harvested tissues. R.D., K.D.G., P.C., A.A.L., J.S.C., C.H., S.V.D., R.R.S. and M.F.C. prepared nucleic acids and sequencing libraries. N.G., A.S., A.O., C.H., P.D.B., S.V.D. and R.R.S. performed bioinformatics analyses. N.G. and M.F.C. drafted the text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Information (Supplemental Data 2)

Supplemental Data 1

Supplemental Data 3

Supplemental Data 4

Supplemental Data 5

Supplemental Data 6

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Texas A&M Agrilife and Texas Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory #124151 to CDJ, SVD, and MFC, Texas A&M and Mexican CONACyT to RRS, SVD and MFC, USDA Formula Animal Health to MFC and SVD, and Mexican National Institute of Fisheries (INAPESCA) to RRS, LGB, ERP, SVD and MFC. The generation of RNA-Seq raw data was outsourced to Ambry Genetics, Aliso Viejo CA. This work used the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE), which is supported by National Science Foundation grant number OCI-1053575, to provide compute time on the Blacklight system at the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center (PSC).

References

- Cock J., Gitterle T., Salazar M. & Rye M. Breeding for disease resistance of Penaeid shrimps. Aquaculture 286, 1–11, DOI 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2008.09.011 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Tran L. et al. Determination of the infectious nature of the agent of acute hepatopancreatic necrosis syndrome affecting penaeid shrimp. Dis Aquat Organ 105, 45–55, Doi 10.3354/Dao02621 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C. et al. Analysis of Litopenaeus vannamei transcriptome using the next-generation DNA sequencing technique. PLoS One 7, e47442, 10.1371/journal.pone.0047442 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H. et al. Trascriptome analysis of the Paci fi c white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei exposed to nitrite by RNA-seq. Fish & shellfish immunology 35, 2008–2016, 10.1016/j.fsi.2013.09.019 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary N. A. et al. Analysis of multiple tissue-specific cDNA libraries from the Pacific whiteleg shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei. Integrative and comparative biology 46, 931–939, 10.1093/icb/icl006 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X. et al. Transcriptome analysis of Litopenaeus vannamei in response to white spot syndrome virus infection. PLoS One 8, e73218, 10.1371/journal.pone.0073218 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clavero-Salas A. et al. Transcriptome analysis of gills from the white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei infected with White Spot Syndrome Virus. Fish & shellfish immunology 23, 459–472, 10.1016/j.fsi.2007.01.010 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robalino J. et al. Insights into the immune transcriptome of the shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei: tissue-specific expression profiles and transcriptomic responses to immune challenge. Physiological genomics 29, 44–56, 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00165.2006 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sookruksawong S., Sun F., Liu Z. & Tassanakajon A. RNA-Seq analysis reveals genes associated with resistance to Taura syndrome virus (TSV) in the Pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. Dev Comp Immunol 41, 523–533, 10.1016/j.dci.2013.07.020 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veloso A., Warr G. W., Browdy C. L. & Chapman R. W. The transcriptomic response to viral infection of two strains of shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Dev Comp Immunol 35, 241–246, 10.1016/j.dci.2010.10.001 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng D. et al. Transcriptome analysis of Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) hepatopancreas in response to Taura syndrome Virus (TSV) experimental infection. PLoS One 8, e57515, 10.1371/journal.pone.0057515 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerenius L. & Soderhall K. Variable immune molecules in invertebrates. The Journal of experimental biology 216, 4313–4319, 10.1242/jeb.085191 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijers R. et al. Structural basis of Dscam isoform specificity. Nature 449, 487–491, nature06147 [pii] 10.1038/nature06147 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L. & Lee T. Molecular diversity of Dscam and self-recognition. Advances in experimental medicine and biology 739, 262–275, 10.1007/978-1-4614-1704-0_17 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung H. Y. et al. Properties of Litopenaeus vannamei Dscam (LvDscam) isoforms related to specific pathogen recognition. Fish & shellfish immunology 35, 1272–1281, 10.1016/j.fsi.2013.07.045 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watthanasurorot A., Jiravanichpaisal P., Liu H., Soderhall I. & Soderhall K. Bacteria-Induced Dscam Isoforms of the Crustacean, Pacifastacus leniusculus. PLoS pathogens 7, e1002062, 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002062 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Bondad-Reantaso M. G., Subasinghe R. P., Josupeit H., Cai J. N. & Zhou X. W. The role of crustacean fisheries and aquaculture in global food security: Past, present and future. Journal of invertebrate pathology 110, 158–165, DOI 10.1016/j.jip.2012.03.010 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley K. M. & Rast J. P. Characterizing immune receptors from new genome sequences. Methods Mol Biol 748, 273–298, 10.1007/978-1-61779-139-0_19 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tassanakajon A., Somboonwiwat K., Supungul P. & Tang S. Discovery of immune molecules and their crucial functions in shrimp immunity. Fish & shellfish immunology 34, 954–967, 10.1016/j.fsi.2012.09.021 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriya Y., Itoh M., Okuda S., Yoshizawa A. C. & Kanehisa M. KAAS: an automatic genome annotation and pathway reconstruction server. Nucleic acids research 35, W182–185, 10.1093/nar/gkm321 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco-Miranda J. S. et al. Crystal structure of the shrimp proliferating cell nuclear antigen: structural complementarity with WSSV DNA polymerase PIP-box. PLoS One 9, e94369, 10.1371/journal.pone.0094369 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attasart P. et al. Inhibition of white spot syndrome virus replication in Penaeus monodon by combined silencing of viral rr2 and shrimp PmRab7. Virus research 145, 127–133, 10.1016/j.virusres.2009.06.018 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann J. A., Kafatos F. C., Janeway C. A. & Ezekowitz R. A. B. Phylogenetic perspectives in innate immunity. Science 284, 1313–1318, DOI 10.1126/science.284.5418.1313 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauton C. & Smith V. J. Adaptive immunity in invertebrates: a straw house without a mechanistic foundation. Bioessays 29, 1138–1146, Doi 10.1002/Bies.20650 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criscitiello M. F. & de Figueiredo P. Fifty shades of immune defense. PLoS pathogens 9, e1003110, 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003110 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderhall K. Special issue: Invertebrate immunity. Developmental and Comparative Immunology 23, 263–266 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. Y. & Soderhall K. Early events in crustacean innate immunity. Fish & shellfish immunology 12, 421–437, DOI 10.1006/fsim.2002.0420 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauton C. & Smith V. Studying immunity at the whole organism level - Reply. Bioessays 30, 406–406, Doi 10.1002/Bies.20737 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lightner D. V. Epizootiology, distribution and the impact on international trade of two penaeid shrimp viruses in the Americas. Rev Sci Tech Oie 15, 579–601 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lightner D. V., Hasson K. W., White B. L. & Redman R. M. Experimental infection of western hemisphere penaeid shrimp with Asian white spot syndrome virus and Asian yellow head virus. J Aquat Anim Health 10, 271–281, Doi 10.1577/1548-8667(1998)0100271:Eiowhp>2.0.Co;2 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Simard Y. & Harvey M. Predation on Northern krill (Meganyctiphanes norvegica Sars). Advances in marine biology 57, 277–306, 10.1016/B978-0-12-381308-4.00010-8 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macklin S. A. Report on the FOCI International Workshop on Recent Conditions in the Bering Sea. 22–26 (National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration Seattle, 1998). [Google Scholar]

- Tsang L. M., Chan T. Y., Ahyong S. T. & Chu K. H. Hermit to King, or Hermit to All: Multiple Transitions to Crab-like Forms from Hermit Crab Ancestors. Systematic biology 60, 616–629, DOI 10.1093/sysbio/syr063 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moret Y. & Siva-Jothy M. T. Adaptive innate immunity? Responsive-mode prophylaxis in the mealworm beetle, Tenebrio molitor. Proceedings. Biological sciences/The Royal Society 270, 2475–2480, 10.1098/rspb.2003.2511 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M. M., Roberts H. L., Sarjan M., Asgari S. & Schmidt O. Induction and transmission of Bacillus thuringiensis tolerance in the flour moth Ephestia kuehniella. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101, 2696–2699, 10.1073/pnas.0306669101 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadd B. M. & Schmid-Hempel P. Insect immunity shows specificity in protection upon secondary pathogen exposure. Current biology: CB 16, 1206–1210, 10.1016/j.cub.2006.04.047 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham L. N., Dionne M. S., Shirasu-Hiza M. & Schneider D. S. A specific primed immune response in Drosophila is dependent on phagocytes. PLoS pathogens 3, e26, 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030026 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth O. et al. Paternally derived immune priming for offspring in the red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum. The Journal of animal ecology 79, 403–413, 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2009.01617.x (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng T. H., Chiang Y. A., Yeh Y. C. & Wang H. C. Review of Dscam-mediated immunity in shrimp and other arthropods. Dev Comp Immunol 46, 129–138, 10.1016/j.dci.2014.04.002 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow S., Dougherty W. J. & Sandifer P. A. Meiotic Chromosome Complements and Nuclear-DNA Contents of 4 Species of Shrimps of the Genus Penaeus. J Crustacean Biol 10, 29–36, Doi 10.2307/1548667 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- Simpson S. The Blue Food Revolution. Sci Am 304, 54–61, DOI 10.1038/scientificamerican0211-54 (2011). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet.journal 17, 10–12 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Haas B. J. et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nature protocols 8, 1494–1512, 10.1038/nprot.2013.084 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M. & Goto S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic acids research 28, 27–30 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conesa A. et al. Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics 21, 3674–3676, 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti610 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Information (Supplemental Data 2)

Supplemental Data 1

Supplemental Data 3

Supplemental Data 4

Supplemental Data 5

Supplemental Data 6