Abstract

Oxidative stress is a common denominator of numerous cardiovascular disorders. Free cellular iron catalyzes formation of highly toxic hydroxyl radicals and iron chelation may thus be an effective therapeutic approach. However, using classical iron chelators in diseases without iron overload poses risks that necessitate more advanced approaches, such as prochelators that are activated to chelate iron only under disease-specific oxidative stress conditions. In this study, three cell membrane-permeable iron chelators (clinically-used deferasirox and experimental SIH and HAPI) and five boronate-masked prochelator analogs were evaluated for their ability to protect cardiac cells against oxidative injury induced by hydrogen peroxide. Whereas the deferasirox-derived agents TIP and TRA-IMM displayed negligible protection and even considerable toxicity, aroylhydrazone prochelators BHAPI and BSIH-PD provided significant cytoprotection and displayed lower toxicity following prolonged cellular exposure compared to their parent chelators HAPI and SIH, respectively. Overall, the most favorable properties in terms of protective efficiency and low inherent cytotoxicity were observed with aroylhydrazone prochelator BSIH. BSIH efficiently protected both H9c2 rat cardiomyoblast-derived cells as well as isolated primary rat cardiomyocytes against hydrogen peroxide-induced mitochondrial and lysosomal dysregulation and cell death. At the same time, BSIH was non-toxic at concentrations up to its solubility limit (600 µM) and 72-hour incubation. Hence, BSIH merits further investigation for prevention and/or treatment of cardiovascular disorders associated with a known (or presumed) component of oxidative stress.

Keywords: iron chelation, deferasirox (ICL670A), salicylaldehyde isonicotinoyl hydrazone (SIH), prochelator, BSIH

Introduction

Iron (Fe) is an essential element for all mammalian cells and is the most plentiful transition metal in the human body. Due to its flexibility as both electron donor and acceptor, Fe is a key cofactor of proteins critical to such basic cellular processes as oxygen transport and storage, electron transport, cellular respiration, DNA, RNA and protein synthesis, cellular proliferation and differentiation and regulation of gene expression [1]. The importance of maintaining Fe homeostasis is highlighted by the fact that imbalance in either direction causes pathophysiological disorders: deficiency leads to anemia, and overload leads to tissue damage and organ failure as a result of Fe-promoted oxidative stress [1]. Redox-active Fe species efficiently catalyze the Haber-Weiss reaction of superoxide radical and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) to yield hydroxyl radicals – the most reactive and toxic form of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [2–4].

Considering the propensity of free Fe to mediate oxidative injury, cells acquire, transport and store Fe by employing dedicated proteins that maintain the intracellular labile and redox-active Fe pool at an appropriate level. Nevertheless, due to the lack of effective body Fe excretion, excess body Fe can accumulate in some diseases with over-active Fe absorption and/or regular blood transfusion therapy, such as β-thalassemia major [1]. In addition, local Fe-mediated oxidative injury may occur even without systemic Fe overload [2–4]. Reactive oxygen or nitrogen species may severely deregulate cellular Fe homeostasis [5]. For example, high cellular levels of superoxide and peroxide species, as well as low pH (both of which occur during myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury), cause Fe release from its storage proteins, thereby increasing the cytosolic pool of labile Fe and exacerbating the production of deleterious ROS [6]. Furthermore, redox-active Fe may also promote formation of ROS within mitochondria and lysosomes [7] and thus propagate the vicious cycle of oxidative injury.

Oxidative stress is a common denominator of a wide range of cardiovascular disorders. These include ischemia/reperfusion injury, cardiac arrhythmias, congestive heart failure, myocarditis, atherosclerosis, hypertension, and the cardiotoxicity of redox-cycling drugs [8]. However, conventional treatment of cardiovascular diseases still lacks the use of antioxidants due to mostly negative study outcomes [9, 10]. Unfortunately, efforts to mitigate oxidative stress have so far primarily focused on administering ROS scavengers, rather than on actual prevention of ROS production. The latter can be achieved with Fe chelators, i.e. agents that form redox-inactive complexes with Fe and block the Fe-dependent and site-specific production of hydroxyl radicals [11–13]. Fe chelators have been tested in numerous cardiovascular diseases [14, 15]. However, progress in this area has been hindered by the lack of suitable ligands. Probably due to its commercial availability, most studies have employed desferrioxamine (DFO), a bacterial siderophore clinically used for lowering the body Fe burden in disorders such as β-thalassemia [13]. Unfortunately, this hydrophilic chelator suffers from poor plasma membrane permeability, resulting in limited access to intracellular labile iron pools [13]. Previous results from our laboratory as well as of other groups have shown promising cardioprotective potential (both in vitro and in vivo) of various small-molecular and lipophilic Fe chelators, both clinically-used agents such as deferasirox (ICL670A) or deferiprone (L1) as well as experimental aroylhydrazone chelators including salicylaldehyde isonicotinoyl hydrazone (SIH) or its novel analog with improved hydrolytic stability HAPI ((E)-N´-[1-(2-hydroxyphenyl)ethyliden] isonicotinohydrazide) [16–22].

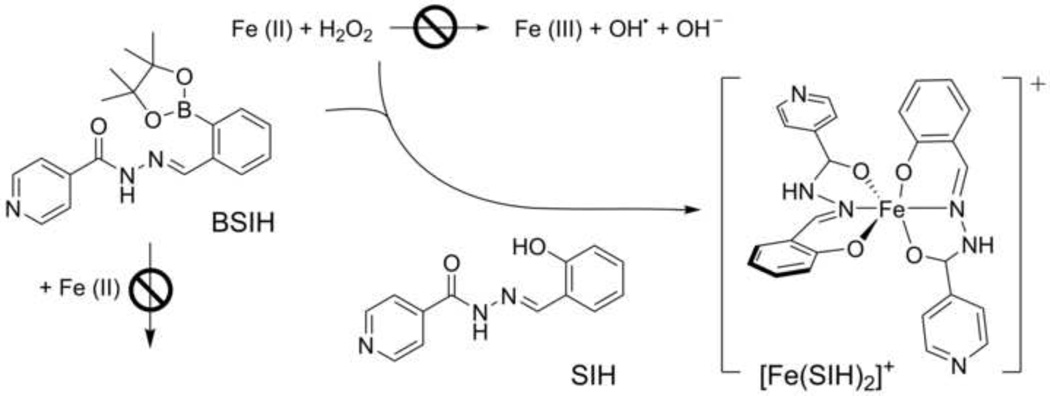

However, the use of Fe chelating agents in states without systemic Fe overload bears a toxicity risk due to chelator-induced deregulation of physiological Fe homeostasis [12]. Hence, for diseases associated with localized Fe-mediated oxidative stress without systemic Fe overload, an optimal chelator should be capable of permeating cell membranes, but preferentially sequester only those Fe ions that are causing damage without withholding Fe or other metals from metalloproteins or inducing systemic metal excretion. To this end, novel boronate-masked prochelators were recently introduced [23]. These prochelators are designed not to bind metal ions unless the protective mask is conditionally removed by H2O2 to reveal an active chelator capable of suppressing Fe-mediated hydroxyl radical generation (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Concept of oxidative stress-activated iron chelation.

Conversion of prochelator BSIH to active chelating agent SIH by reaction with H2O2.

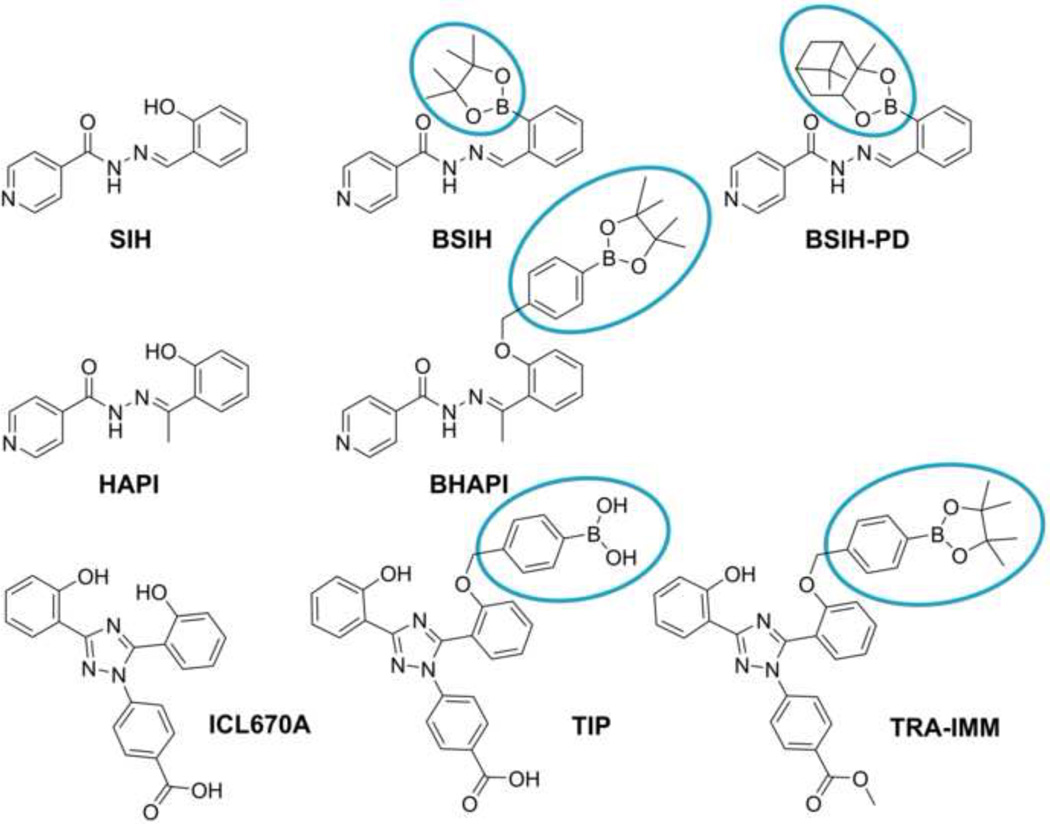

The first of the five prochelators examined in the present study (Fig. 2), BSIH, contains a boronic ester in place of a phenolic oxygen that is a key donor atom of the well-established experimental antioxidant aroylhydrazone metal chelator SIH [23–25]. BSIH-PD is a BSIH analog that contains a pinanediol boronic ester instead of pinacol. The prochelator BHAPI is derived from HAPI, an SIH analog with improved hydrolytic stability [26], but the direct boronic ester group of BSIH is replaced with a self-immolative spacer that undergoes spontaneous elimination after reacting with H2O2 [27]. In addition, two novel triazole prochelators were derived from the clinically-used Fe chelator ICL670A, both with the self-immolative spacer and boronic acid (TIP) or its pinacol diol ester (TRA-IMM) [27]. In this study, the parent chelators and their prochelators were examined and compared for their relative affinity for Fe ions (before and after ROS exposure), ability to penetrate cells and bind labile cellular Fe, potential to protect cardiac cells against the toxic action of model oxidative stress induced by cellular exposure to H2O2, as well as the inherent toxicities of the examined agents.

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of compounds evaluated in this study. Chelators are shown on the left, and their corresponding oxidative stress-activated prochelators on the right, with masking group highlighted.

Methods

Chemicals

Tested compounds (Fig. 2): (E)-N´-(2-hydroxybezylidene) isonicotinohydrazide (SIH) and (E)-N´-[1-(2-hydroxyphenyl)ethyliden] isonicotinohydrazide (HAPI), (E)-N´-[2-(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-[1,2,3]dioxaborolan-2-yl)-benzylidene] isonicotinohydrazide (BSIH), (E)-N´-(1-(2-((4-(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,2,3-dioxoborolan-2-yl)benzyl)oxy)phenyl)ethylidene) isonicotinohydrazide (BHAPI), methyl-4-(3-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-5-(2-((4-(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxoborolan-2-yl)benzyl)oxy)phenyl)-1H-1,2,4-triazol-1-yl) benzoate (TRA-IMM) and 4-(5-(2-((4-boronobenzyl)oxy)phenyl)-3-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-1H-1,2,4-triazol-1-yl)benzoic acid (TIP) ware synthesized as described previously [23, 25–29]. 4-[(3Z,5E)-3,5-bis(6-oxo-1-cyclohexa-2,4-dienylidene)-1,2,4-trizolidin-1-yl] benzoic acid (ICL670A) was purified from commercial pharmaceutical preparation of Novartis (Basel, Switzerland). (E)-N´-[2-(3a,5,5-trimethylhexahydro-4,6-methanobenzo[d][1,2,3]dioxaborolan-2-yl)benzylidene] isonicotinohydrazide (BSIH-PD) was synthesized at Duke University (Durham, NC).

In order to prepare BSIH-PD ((E)-N'-(2-(5,5,7a–trimethylhexahydro-4,6-methanobenzo[d][1,3,2]dioxaborol-2-yl)benzylidene)isonicotinohydrazide), a portion of BASIH was first prepared from equimolar quantities of isonicotinic acid hydrazide and (2-formylphenyl)-boronic acid as previously reported [25]. Equimolar quantities of BASIH (0.20 g; 0.8 mmol) and (1R, 2R, 3S, 5R)-pinanediol (0.136 g; 0.8 mmol) were added to 50 ml of a 9:1 mixture of toluene and DMF in a round-bottom flask. The reaction solution was heated under N2 at 150 °C for 3 h. The solvent was removed by rotary evaporation and the resulting solid triturated 3 times with 10 ml portions of diethyl ether. The solid was dried in vacuo to give 230 mg of product (71 % yield). Purity was confirmed by LC/MS, which showed one clean peak eluting at 17.6 min with a corresponding m/z of 404.3. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ ppm: 12.24 (s, 1H), 8.99 (s, 1H), 8.79 (d, J = 5.60 Hz, 2H), 8.03 (d, J = 7.60 Hz, 1H), 7.83 (d, J = 6.00 Hz, 2H), 7.75 (d, J = 7.60 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (t, J = 7.60, 7.60 Hz, 1H), 7.46 (t, J = 7.20, 7.20 Hz, 1H), 4.58 (d, J = 8.00 Hz 1H), 2.39 (m, 1H), 2.24 (m, 1H), 2.11 (m, 1H), 1.95 (m, 2H), 1.48 (s, 3H), 1.28 (s, 3H), 1.13 (d, J = 10.80 Hz, 1H), 0.87 (s, 3H). HRMS (ES+) 404.2112 (C23H26BN3O3 requires 403.2067) (MH+).

Constituents for various buffers as well as other chemicals were purchased from Sigma (Germany), Fluka (Germany), Merck (Germamy), or Penta (Czech Republic) and were of the highest available pharmaceutical or analytical grade.

Cell cultures

The H9c2 cardiomyoblast cell line derived from embryonic rat heart tissue [30] was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, U.S.A.). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Lonza, Belgium) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Lonza, Belgium), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Lonza, Belgium) and 10 mM HEPES buffer (Sigma, Germany) in 75 cm2 tissue culture flasks (Techno Plastic Products (TPP), Switzerland) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air. Subconfluent cells were subcultured twice weekly. 24 h before experiments, the medium was changed to serum- and pyruvate-free DMEM (Sigma, Germany). Serum deprivation was used to stop cellular proliferation to mimic the situation in post-mitotic cardiomyocytes, whereas pyruvate was omitted because it is an antioxidant and may interfere with ROS-related toxicity. The lipophilic compounds were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma, Germany), which was used at final concentration 0.1% in all experimental groups. At the concentration used it had no effect on cellular viability.

Primary cultures of neonatal ventricular cardiomyocytes (NVCM) were prepared from 1–3 day old Wistar rats. All the procedures have been supervised and approved by the Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Pharmacy, Charles University in Prague. Briefly, neonatal hearts were minced in ADS buffer (1.2 mM MgSO4 7H2O; 116 mM NaCl; 5.3 mM KCl; 1.13 mM NaH2PO4 H2O; 20 mM HEPES) on ice, digested at 37°C with type II collagenase (Invitrogen, U.S.A.). After pre-plating on 150 mm Petri dishes for approximately 20 hearts to minimize non-myocyte contamination, cells were plated on gelatin-coated 12-well plates at a density of 80,000 cells per well. NVCM were cultured at 37°C and 5 % CO2 in the DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10 % horse serum (HS; Lonza, Belgium), 4 mM pyruvate, 5 % FBS and 1 % penicillin/streptomycin. Newly isolated NVCMs were left for 40 h to attach properly and form a culture of spontaneously beating cardiomyocytes. Then the medium was changed for 24 h to DMEM/F12 supplemented with 4 mM pyruvate, 5 % FBS and 1 % penicillin/streptomycin. For the experiments the medium was changed to serum- and pyruvate-free DMEM/F12 with 1 % penicillin/streptomycin. The cells were maintained in this medium until the end of experiments.

Determination of Fe-chelating efficiencies in solution

Measurements of calcein fluorescence intensity were used to asses Fe chelation efficiencies of tested substances [31]. Calcein is a fluorescent probe (λex = 486 nm and λem = 517 nm) that readily forms complexes with Fe ions, which quench its fluorescence. The addition of an Fe-chelating agent to the Fe-calcein complex leads to the removal of Fe from calcein with new complex formation. The calcein dequenching is accompanied by an increase in the fluorescence intensity. The calcein complex (free acid, 20 nM) with ferrous diammonium sulphate (FAS 200 nM; Sigma, Germany) was prepared in HEPES-buffered saline (HBS; 150 mM NaCl, 40 mM HEPES, pH 7.2). Calcein and FAS were continuously stirred for 45 min in the dark after which > 90 % of the fluorescence was quenched. Then 100 µl of the Fe-calcein complex was pipetted into a 96-well plate and a baseline measurement was started. 100 µl of the assayed Fe-chelator or prochelator solution under investigation was added, yielding a final concentration of 5 µM, either alone or with various concentrations of H2O2. Prochelators were preincubated with H2O2 one hour before the measurement. The change in fluorescence intensity was measured as a function of time at 25 °C using a Tecan plate reader for 30 min. The Fe-chelation efficiency of a given substance (with or without H2O2) was expressed as a percentage of efficiency of the reference chelator SIH (100 %).

Assessments of cell membrane permeability and access to the intracellular labile Fe pool

The experiments were performed according to Glickstein et al. [32] with slight modifications. H9c2 cells were seeded in 96-well plates (10,000 cells per well). Prior to the experiment, cells were loaded with Fe by incubating with 100 µM ferric ammonium citrate (FAC) in serum-free medium for 24 h and then washed. To prevent potential interference (especially with regard to various trace elements), the medium was replaced with ADS buffer (pH 7.4) supplemented with 1 mM CaCl2, and 5 mM glucose. Cells were then loaded with 1 µM of calcein green acetoxymethyl ester (Calcein-AM, Molecular Probes/Invitrogen, Czech Republic) for 30 min at 37 °C and washed. Calcein-AM is cell-permeable, and is converted into cell membrane-impermeable calcein by intracellular esterases that cleave the acetoxymethyl groups. Fluorescence of intracellular calcein is quenched by FAC. Intracellular fluorescence (λex = 488 nm; λem = 530 nm) was then followed as a function of time (1 min before and 10 min after the addition of tested compounds with or without H2O2) using a Tecan Infinite 200 M micro-plate spectrophotometer (Tecan, Austria)

Neutral red uptake assay for measurements of cellular viability

The cellular viability of H9c2 cells was determined using an assay based on the ability of viable cells to incorporate neutral red (NR; Sigma, Germany). This weak cationic dye readily penetrates intact cell membranes and accumulates in the lysosomes of viable cells [33]. H9c2 cells seeded in a 96-well plate at a density 10,000 cells per well were incubated with the tested compounds or H2O2 and FAC (alone or in combinations) for 24 or 72 h. At the end of incubation, half of the medium volume had been removed from each well and then the same volume of medium with NR was added yielding final NR concentration of 40 µg/ml. After 3 h at 37°C, the supernatant was discarded and the cells were fixed in 0.5% formaldehyde supplemented with 1% CaCl2 for 15 min. The cells were then twice washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS; Sigma, Germany) and solubilized with 1% acetic acid in 50% ethanol during 30-min continuous agitation. The absorption of soluble NR was measured using the Tecan plate reader at λ = 540 nm. The viability of experimental groups was expressed as a percentage of the untreated control (100 %).

Real-time assessments of cellular viability

The real-time cell analyzer (RTCA xCELLigence System; Roche, Germany) was used to monitor cellular events without the incorporation of labels. It is based on electrical impedance measurement across micro-electrodes integrated on the bottom of tissue culture E-plates. The impedance measurement provides quantitative information about the biological status of the cells, including cell number, viability and morphology [34]. The H9c2 cells were seeded in a 16-well E-plate at a density 10,000 cells per well and incubated with the tested compounds or H2O2 (alone or in combinations) for 42 h.

Epifluorescence microscopy for determination of cellular morphology and mitochondrial inner membrane potential

Photomicrographs were obtained using the epifluorescence inverted microscope Eclipse TS100 (Nikon, Japan) equipped with digital cooled camera (1300Q, VDS Vosskühler, Germany) and software NIS-Elements AR 3.10 (Laboratory Imaging, Czech Republic). Mitochondrial activity was assessed using the JC1 probe (5,5´,6,6´-tetrachlor-1,1´,3,3´-tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide; Molecular Probes/Invitrogen, Czech Republic). JC1 becomes non-specifically accumulated in cellular cytosol as a green fluorescent monomer (λex = 480 nm; λem = 535 nm). In metabolically-active mitochondria with polarized inner membrane, JC1 monomers flock into red fluorescent J-aggregates (λex = 560 nm; λem = 630 nm). Cells were seeded on 6-well (H9c2) and 12-well (NVCM) plates and incubated for 24 h with tested compounds and then loaded with 2 µM JC1 for 30 min at 37 °C after which the medium was replaced with PBS.

Data analysis

In this study, the statistical software SigmaStat for Windows 3.5 (SPSS, U.S.A.) was used. Data are presented as mean ± SD (standard deviation). Statistical significance was determined using ANOVA with a Bonferroni post hoc test (comparisons of multiple groups against a corresponding control). Results were considered to be statistically significant when p < 0.05. The concentrations of tested compounds inducing 50% toxicity / viability decrease (median toxic concentration; TC50) and the concentration leading to 50% protection from toxicity induced by H2O2 (median effective concentration; EC50) were calculated using CalcuSyn 2.0 software (Biosoft, U.K.). The graphs were created using GraphPad Prism 5.04 for Windows.

Results

Determination of Fe-chelating efficiencies in solution

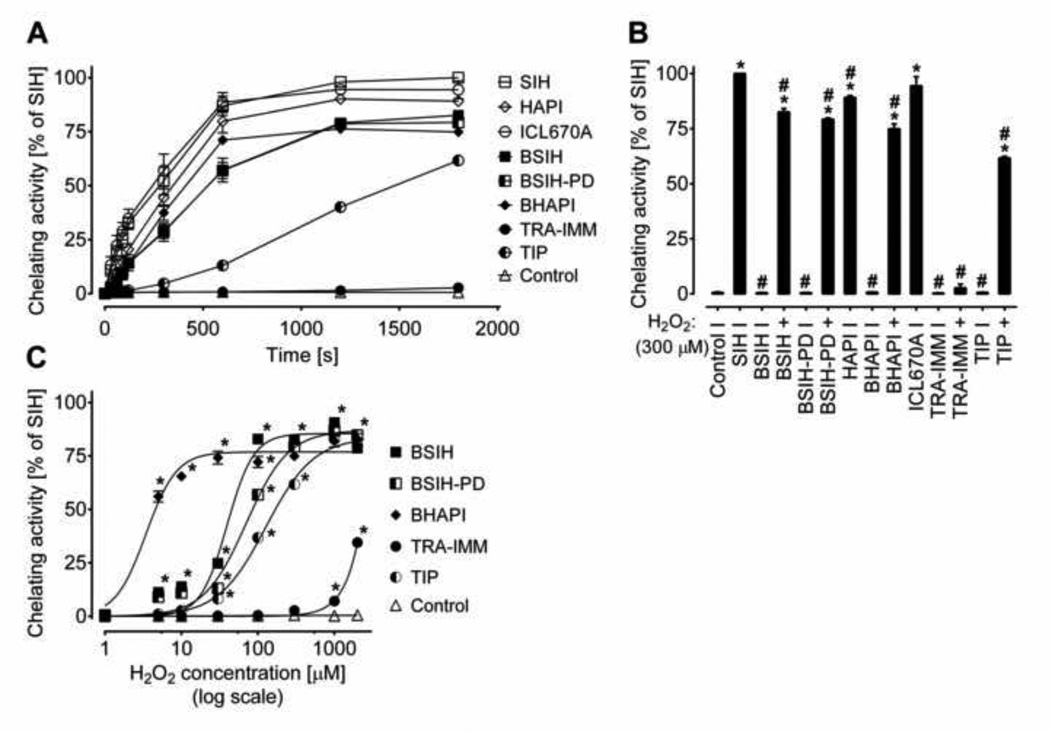

Fe chelation properties of the tested compounds were first assessed in a cell-free system using the well-established calcein assay [31], where the fluorescence intensity was followed for 30 minutes after the addition of (pro)chelator. As seen in Fig. 3A–B, the three parent chelators, SIH, HAPI and ICL670A (all 5 µM), displayed comparable Fe-binding properties as they were all able to quickly and efficiently dequench the calcein fluorescence. In contrast, none of the five examined prochelators showed any measureable increase in calcein fluorescence as compared to control in the absence of H2O2 (Fig. 3B). In contrast, preincubation of BSIH, BSIH-PD, BHAPI and TIP for 1 h with a 60-fold molar excess of H2O2 resulted in calcein dequenching, as seen in Fig. 3A–B. Whereas the Fe chelation efficiency of H2O2-activated BSIH, BSIH-PD and BHAPI reached about 80 % of the SIH-induced fluorescence intensity, the activation of TIP displayed slower dynamics of calcein dequenching, reaching ≈ 60 % of the SIH at the measured time-point. The prochelator TRA-IMM did not show a significant increase in fluorescence intensity (Fig. 3A–B). In addition to the fixed 1:60 prochelator : H2O2 ratio, activations of prochelators (all 5 µM) by various concentrations of H2O2 were determined following 1 h H2O2 exposure and 30 min calcein dequenching. As seen in Fig. 3C, BHAPI was the most H2O2-responsive prochelator, as significant fluorescence increase occurred following its exposure to as low as 5 µM H2O2 concentration (i.e., a 1:1 BHAPI : H2O2 molar ratio). BSIH, BSIH-PD and TIP required higher H2O2 concentrations for their activation. TRA-IMM displayed very poor activation and induced significant calcein dequenching only following the exposure to the two highest tested concentrations of H2O2 (1 mM and 2 mM), i.e., 200- and 400-fold molar excess over the prochelator (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3. Iron-chelating efficiencies of chelators (SIH, HAPI, ICL670A) and prochelators (BSIH, BSIH-PD, BHAPI, TRA-IMM, TIP) in solution and activation of prochelators by H2O2 to active chelators.

Iron chelating activities of tested compounds (alone and following exposure to H2O2) were evaluated by the assessment of Fe displacement from its complex with calcein in buffered solution (pH 7.2). The effectiveness of chelation is expressed as a percentage of the efficiency of SIH (100 %). (A) Dynamics of the dequenching process: mean changes in calcein fluorescence intensity recorded over 30 min after chelators (SIH, HAPI, ICL670A) (all 5 µM) or prochelators (BSIH, BSIH-PD, BHAPI, TRA-IMM, TIP, all 5 µM and pre-incubated with 300 µM H2O2) were mixed with Fe calcein. (B) Mean changes in fluorescence intensity following 30 min of incubation with tested compounds (all 5 µM); (C) Dependence of prochelators’ conversion to active chelators on various concentrations of H2O2. Data are presented as means ± SD; n = 4; statistical significance (ANOVA, p ≤ 0.05): *, as compared to control; #, compared to SIH.

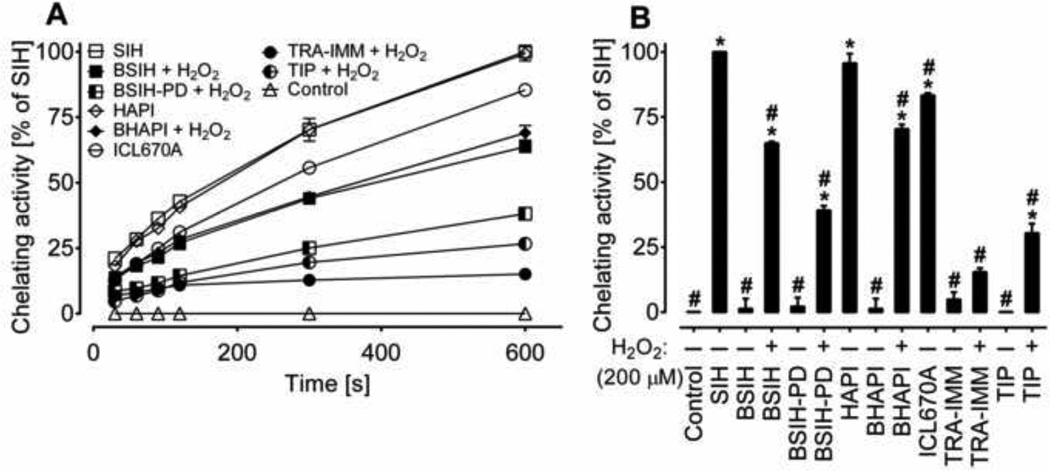

Assessment cell membrane permeability and access to the intracellular labile iron pool

The calcein-AM assay [32] was used to compare the ability of tested compounds to access the labile Fe pool in H9c2 cells. Increases in intracellular fluorescence intensity (caused by the removal of Fe from the intracellularly-trapped complex with calcein) were monitored during a 10-min incubation of cells with chelators and prochelators (all 100 µM concentration) or with these compounds applied to the cells together with 200 µM H2O2, i.e., a dose used for cytotoxicity experiments (see below). All of the three parent chelators, SIH, HAPI and ICL670A, were able to efficiently chelate intracellular Fe. SIH and HAPI displayed the highest chelation efficiency, whereas ICL670A reached ≈ 80 % of the fluorescence increase induced by SIH (Fig. 4). In the absence of added H2O2, none of the five prochelators showed any significant increase in calcein fluorescence (Fig. 4). On the other hand, all of the H2O2-activated prochelators showed a significant increase in fluorescence intensity. BHAPI and BSIH reached ≈70 % of chelating activity of the reference compound SIH. Slight, yet significant increase in calcein fluorescence was observed also with H2O2-activated ICL670A-derived prochelators TIP and TRA-IMM (Fig 4).

Figure 4. Intracellular iron chelation efficiencies of the tested iron chelators (SIH, HAPI, ICL670A) and prochelators (BSIH, BSIH-PD, BHAPI, TRA-IMM, TIP).

Increase in fluorescence after displacement of intracellular labile iron from its complex with intracellularly-trapped calcein in H9c2 cells following the extracellular addition of Fe chelators and prochelators. (A) The time-course of fluorescence change following the addition of chelators or prochelators in combination with 200 µM H2O2. (B) Mean changes in fluorescence intensity following a 10 min incubation with chelators, prochelators and 200 µM H2O2 (alone or in combinations). The effectiveness of chelation is expressed as a percentage of the efficiency of SIH (100 %). Data are presented as means ± SD; n = 4; statistical significance (ANOVA, p ≤ 0.05): *, as compared to control; #, compared to SIH.

Cytoprotective properties of Fe chelators and prochelators against oxidative injury

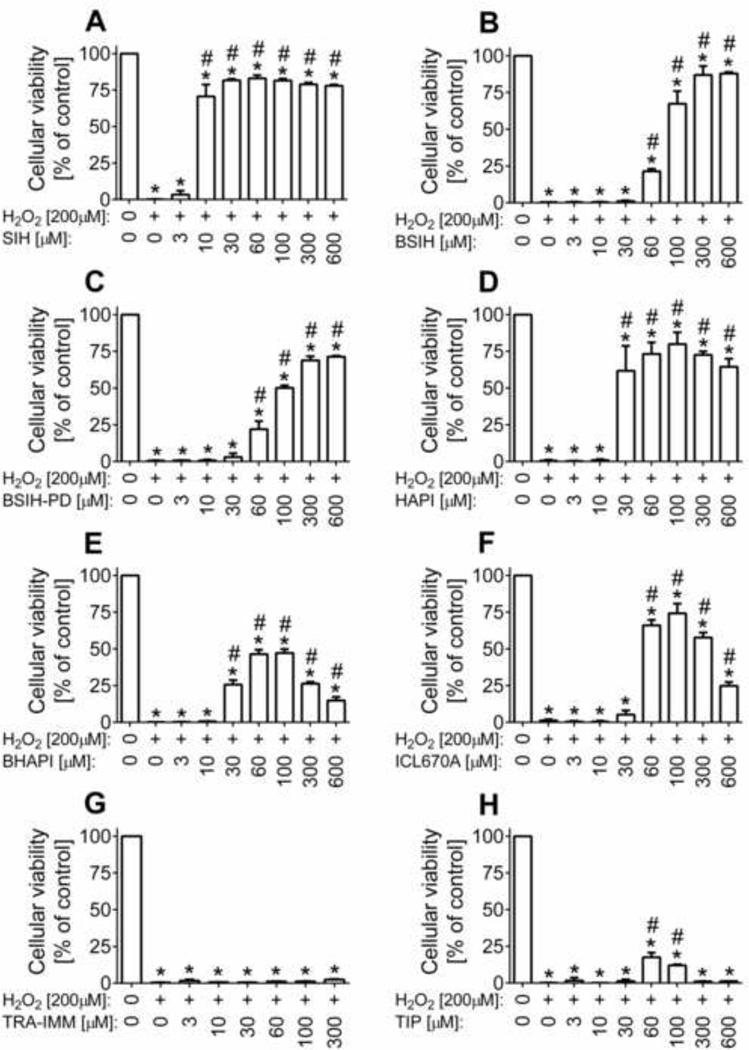

The ability of the examined agents to protect the H9c2 cell line against model oxidative injury was assessed by the neutral red uptake assay after a 24 h exposure of cells to 200 µM H2O2 [33]. As seen in Fig. 5, all three parent chelators dose-dependently protected the H9c2 cells against the complete viability loss induced by H2O2. Their EC50 values, i.e., concentrations reducing the H2O2 toxicity to 50 % of the viability of untreated control cells, are summarized in Table 1. SIH was effective at the lowest concentrations tested – from 10 µM (which is 20-fold lower than the concentration of H2O2). HAPI was able to significantly protect the cells at 30 µM concentration and higher. ICL670A was effective at 60 µM; however, a bell-shaped dose-response occurred as concentrations ≥ 300 µM showed a considerable viability reduction. All three chelators showed an optimal dose that was able to restore viability to ≈ 75 % of the untreated control group of cells. On the contrary, the various prochelators differed considerably in their protective abilities: TRA-IMM did not increase cellular viability at any of the tested concentration up to its solubility limit (300 µM). TIP showed only a slight protective effect at concentrations of 60 and 100 µM. BHAPI was able to preserve viability to nearly 50 % of control cells at its 60 and 100 µM concentrations. SIH-derived prochelators displayed the best protective properties: BSIH-PD and especially BSIH significantly protected H9c2 cells at concentrations ≥ 60 µM. At concentrations ≥ 300 µM, their protective effect was comparable to or even slightly higher (in the case of BSIH) than the cytoprotection afforded by the parent chelator SIH.

Figure 5. Effects of chelators (SIH, HAPI and ICL670A) and prochelators (BSIH, BSIH-PD, BHAPI, TRA-IMM and TIP) on cellular toxicity induced in H9c2 cells by a 24 h exposure to 200 µM H2O2.

Protective properties of chelators (A, D, F) and prochelators (B, C, E, G, H) were determined by neutral red uptake assay and expressed as a percentage of the untreated control group (100 %). Data are presented as means ± SD; n = 3–4; statistical significance (ANOVA, p ≤ 0.05): *, as compared to the control (untreated) group; #, compared to the 200 µM H2O2 group.

Table 1.

Comparison of protective efficiencies against cellular oxidative injury induced by 24 h exposure of cells to 200 µM H2O2 and short-term (24 h) and long-term inherent (72 h) toxicities of iron chelators and prochelators in H9c2 cardiomyblast-derived cell line.

| (Pro)chelator | EC50 [µM] (24 h) |

TC50 [µM] (24 h) |

TC50 [µM] (72 h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SIH | 8.0 ± 0.4 | > 600 | 53.7 ± 4.4 |

| BSIH | 83.9 ± 5.9* | > 600 | > 600* |

| BSIH-PD | 101.6 ± 6.1* | > 600 | 389.6 ± 42.8* |

| HAPI | 28.4 ± 5.3 | > 600 | 15.9 ± 0.3 |

| BHAPI | Ø* | 363.9 ± 36.2* | 37.1 ± 7.7* |

| ICL670A | 52.9 ± 1.7 | 316.7 ± 32.5 | 2.6 ± 0.3 |

| TRA-IMM | Ø* | 80.0 ± 18.8* | 6.3 ± 0.4 |

| TIP | Ø* | 27.4 ± 3.7* | 16.8 ± 2.5* |

EC50 - concentration of (pro)chelator reducing the toxicity induced by 24 h of incubation with H2O2 to 50 % of the viability of control (untreated) cells; TC50 - (pro)chelator concentration inducing 50 % viability reduction as compared to control (untreated) cells following a 24-h or 72-h incubations. Studies were performed using the neutral red uptake assay. Data are presented as means ± SD; n = 3–4; statistical significance (ANOVA, p ≤ 0.05)

prochelator as compared to relevant parent chelator.

Given the efficacy of SIH and BSIH to protect H9c2 cells against H2O2-induced cytotoxicity, the protective properties of these agents were also assessed in H9c2 cells against toxicity caused by other pro-oxidant xenobiotics, namely tert-butyl hydroperoxide (tBHP; 100 µM), the redox-cycling herbicide paraquat (3 mM), the synthetic catecholamine isoprenaline (300 µM) and the anthracycline anticancer agent doxorubicin (3 µM). Both SIH and BSIH significantly protected cells against injury caused by all these pro-oxidants, although the protective efficiency of 600 µM BSIH was consistently lower than that of 100 µM SIH (Supplementary data; Fig. S1).

The cytoprotective effects of SIH and BSIH were also tested on other cell lines, including 3T3 rat embryonal fibroblasts, HaCaT human keratinocytes, HepG2 cells derived from human liver carcinoma, and undifferentiated and differentiated neuronal PC12 cells, derived from rat adrenal gland pheochromocytoma. Both SIH and BSIH significantly protected all cell lines from H2O2-induced toxicity (Supplementary data; Fig. S2).

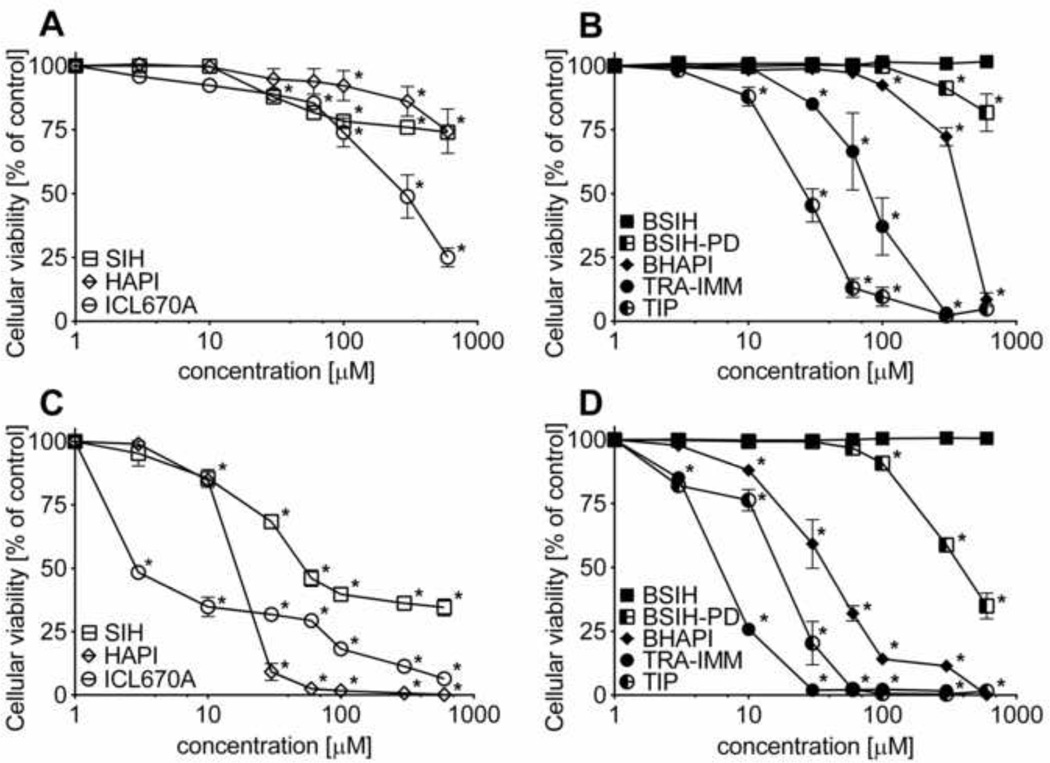

Inherent toxicities of chelators and prochelators

The neutral red uptake assay was used to examine the inherent toxicities of each agent to H9c2 cells. Apart from the 24 h exposures directly corresponding to the cytoprotection experiments (Fig. 6A–B), cells were also incubated with the (pro)chelators for 72 h to assess their toxicities following long-term exposures (Fig. 6C–D). To compare the individual agents, TC50 values were determined at each time point as concentrations inducing 50 % viability loss as compared to untreated control cells (Table 1). Except for BSIH, all the tested compounds induced dose-dependent decreases of cellular viability. Following both the 24 and 72 h exposure times, HAPI and SIH displayed lower toxicity as compared to ICL670A (Fig. 6A,C, Table 1). Whereas HAPI was the least toxic parent chelator in short-term exposures, following the 72 h incubations, its toxicity was markedly augmented, particularly at higher (≥ 30 µM) concentrations. The prochelators TIP, TRA-IMM and BHAPI were more toxic than their parent chelators ICL670A or HAPI following 24 h exposures, but induced lower viability reduction after the 72 h incubations. BSIH and BSIH-PD were less toxic than SIH at both time points. This diminished toxicity was particularly pronounced in the case of BSIH, which did not show any sign of viability reduction even after the 72 h incubation (Fig. 6D). In addition, H9c2 cells were further incubated with BSIH for up to 7 days (168 h) and only minimal viability loss was observed even with its highest achievable (600 µM) concentration (reduction to 92 % cellular viability of untreated control; not shown).

Figure 6. Inherent toxicities of tested compounds - iron chelators (SIH, HAPI and ICL670A) and prochelators (BSIH, BSIH-PD, BHAPI, TRA-IMM and TIP).

H9c2 cells were incubated with increasing concentrations (log scale) of chelators (SIH, HAPI and ICL670A) and prochelators (BSIH, BSIH-PD, BHAPI, TRA-IMM and TIP) for 24 h (A, B) or 72 h (C, D). The cellular viabilities were determined by neutral red uptake assay and expressed as a percentage of the untreated control group (100 %). Data are presented as means ± SD; n = 3–4; statistical significance (ANOVA, p ≤ 0.05): *, as compared to the control.

To examine possible mechanism(s) of toxicities of tested compounds, we measured markers for both autophagy and apoptosis. Fluorescence microscopy using the monodansyl cadaverine probe failed to demonstrate any significant signs of autophagy (data not shown). In contrast, after 72 h incubation with H9c2 cells, all the examined chelators and prochelators caused increases in the activities of caspases 8 and 9, which are key extrinsic (receptor-mediated) and intrinsic (mitochondrial) initiators, respectively, of the apoptotic programmed cell death pathway. Activity of the execution caspases 3/7 also increased. In these experiments, the (pro)chelators were assayed at concentrations that induced viability reduction to ≈ 30 – 50 % of control in previous experiments, or at the highest achievable (600 µM) concentration for BSIH. BSIH and BSIH-PD showed the lowest caspase activation, whereas TRA-IMM and TIP showed the highest propensity for caspase activation (Supplementary data; Fig. S3).

Apart from the H9c2 cardiomyoblasts, the toxicities of SIH and BSIH were also tested on other cell lines. BSIH, assayed at its highest achievable (600 µM) concentration, was in all cells consistently less toxic than SIH (100 µM). BSIH did not show any signs of toxicity on HaCaT keratinocytes and caused only slight viability reduction on 3T3 fibroblast cells. In the case of hepatic HepG2 and neuronal PC12 cells, 600 µM BSIH caused significant viability reduction to ≈ 70 – 75 % of the untreated control cells (Supplementary data; Fig. S4).

The neutral red uptake assay was also used to assess the role of Fe in the toxicities of the tested agents following their 72 h incubations with H9c2 cells. In these experiments, the (pro)chelators were assayed at concentrations that were in previous experiments shown to induce viability reduction to ≈ 30 – 50 % of control and combined with ferric ammonium citrate (FAC), which alone induced dose-dependent viability reduction at concentrations higher than 15 µM (Fig. 7A). As BSIH did not induce toxicity on its own, it was combined at its highest achievable concentration of 600 µM with FAC. All the examined chelators are "tridentate" and were therefore combined with concentrations of Fe corresponding to the iron binding equivalent (IBE) of 1 (2:1 chelator : Fe ratio) as well as concentrations of FAC that were 2-fold higher (1:1 chelator : Fe ratio) and 2-fold lower (4:1 chelator : Fe ratio). As seen in Fig. 7B, Fe supplementation led to a significant reduction, or even a complete loss of chelators’ toxicities. Combined, these results show that Fe-loaded chelators are non-toxic, suggesting that major part of the toxicity of the free ligands is associated with Fe depletion. The only exception was the 1:1 SIH-Fe complex, which was highly toxic at the tested concentration of 100 µM, perhaps due to the three free (uncomplexed) coordination sites of the Fe ions. Neither HAPI nor ICL670A induced marked toxicity at the 1:1 chelator-Fe ratio. Addition of FAC resulted in only slight decreases of the toxicities of prochelators. The toxic effect of BSIH-PD was even additive to that of FAC. On the other hand, non-toxic BSIH was able to significantly reduce the inherent toxicity of FAC (Fig. 7C).

Figure 7. Role of iron in toxicity of tested compounds - iron chelators (SIH, HAPI and ICL670A) and prochelators (BSIH, BSIH-PD, BHAPI, TRA-IMM and TIP).

H9c2 cells were incubated with ferric ammonium citrate chelators (FAC; A), iron chelators SIH, HAPI and ICL670A (B) and prochelators BSIH, BSIH-PD, BHAPI, TRA-IMM and TIP (C) alone or in combinations. The cellular viabilities were determined by neutral red uptake assay and expressed as a percentage of the untreated control group (100 %). Data are presented as means ± SD; n = 4; statistical significance (ANOVA, p ≤ 0.05): *, as compared to the control; # as compared to (pro)chelator without FAC.

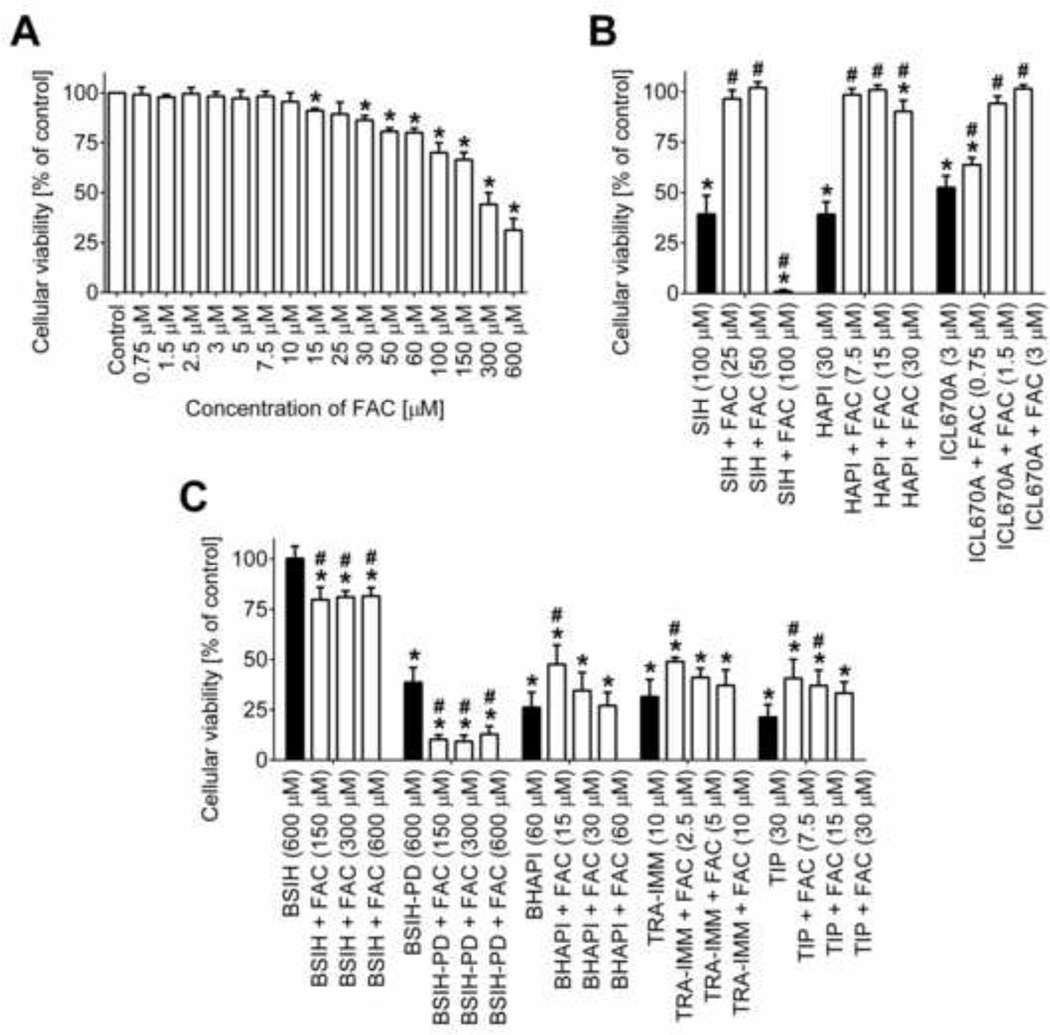

Real-time assessments of cellular viability

In addition to standard determinations of cellular viabilities at the ends of 24 or 72 h incubations, toxic and protective effects of SIH and BSIH (both 100 µM) were assessed in H9c2 cells using the xCELLigence System for label-free and real-time monitoring of cell viability [34]. As seen in Fig. 8, BSIH displayed lack of inherent toxicity as its cellular index curve closely followed that of the untreated control, whereas in SIH-exposed cells, gradual decrease in cellular viability was observed in the time-course of the experiment. Exposure of the cells to 200 µM H2O2 resulted in an abrupt and complete viability loss within 4 h, whereas both SIH and BSIH significantly slowed down the process of H2O2-induced viability loss (Fig. 8).

Figure 8. Dynamic monitoring of cellular viability using the xCELLigence System.

(A) Typical experiment recording when H9c2 cells were incubated with iron chelator SIH or prochelator BSIH (both 100 µM) to determine their inherent toxicities and protective efficiencies against the toxicity induced by exposure to H2O2 (200 µM). The cell index was monitored every 5 min throughout the experiment. (B) Mean cell index values after a 42 h incubation with tested compounds. Results are expressed as means ± SD; n = 3; statistical significance (ANOVA, p < 0.05): *, as compared to control group; #, compared to the H2O2-treated group.

Lysosomal integrity, mitochondrial inner membrane potential and cellular morphology assessments

Lysosomal destabilization and rupture may be important early events in apoptosis caused by oxidative stress as well as a variety of other agents [35]. Hence, using epifluorescence microscopy with the LysoTracker Blue probe, we examined the lysosomal integrity of H9c2 cells exposed for 4 h to the (pro)chelators (all 100 µM) - alone or with 200 µM H2O2. As seen in Fig. S5 (Supplementary data), whereas TRA-IMM induced a slight decrease in blue lysosomal fluorescence, none of the other chelators or prochelators caused apparent differences in LysoTracker staining, suggesting lack of early lysosomal destabilization due to these agents. Four-hour exposure of the cells to H2O2 induced complete loss of lysosmal integrity. With the exception of TRA-IMM, which showed no sign of protection, all the other examined chelators or prochelators were able to reduce or completely prevent lysosomal destabilization induced by H2O2.

Epifluorescence microscopy with the JC1 probe was then used to assess the inner mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm). H9c2 cells were incubated for 24 h with tested compounds (all 100 µM) alone or in combination with H2O2 (200 µM). As seen in Fig. S6 (Supplementary data), the chelators SIH, HAPI and particularly ICL670A induced slight to moderate reduction of red fluorescence intensity and also slight increase in green fluorescence, indicating slow and transient loss of ΔΨm. The most pronounced transition from red to green fluorescence was observed with prochelators TRA-IMM and TIP, whereas BSIH and BSIH-PD did not induce any signs of mitochondrial depolarization. The H2O2-treated cells displayed a distinct red to green fluorescence transition indicating complete ΔΨm dissipation. Whereas TRA-IMM and TIP were unable to effect the H2O2-induced mitochondrial injury, all the other examined chelators and prochelators reduced the H2O2-induced ΔΨm loss.

With respect to cellular morphology, exposure of H9c2 cells for 24 h to most chelators and prochelators (all 100 µM) resulted in rather non-specific signs of toxicity that mostly involved gradual disruption of cellular monolayers and in some cases formation of peripheral plasma membrane blebs. The severity of morphological changes generally corresponded with their toxicity determined with the neutral red uptake assay. Distinct cellular shrinkage and disintegration to particles with apoptotic appearance was observed in the case of prochelators TRA-IMM and TIP. BSIH induced no apparent morphological signs of toxic cellular injury. The incubation of H9c2 cells with 200 µM H2O2 was accompanied by conspicuous membrane blebbing and retraction of filopodia, which was later followed by nuclear condensation and transition of cells from spindle-like to saccular cytosolic appearance. In individual cells, these changes usually took place 2 – 4 h after the start of H2O2 exposure. With exceptions of TRA-IMM and TIP, all the chelators and prochelators (100 µM) were distinctively able to prevent the morphology changes induced by H2O2 (Supplementary data; Fig. S7).

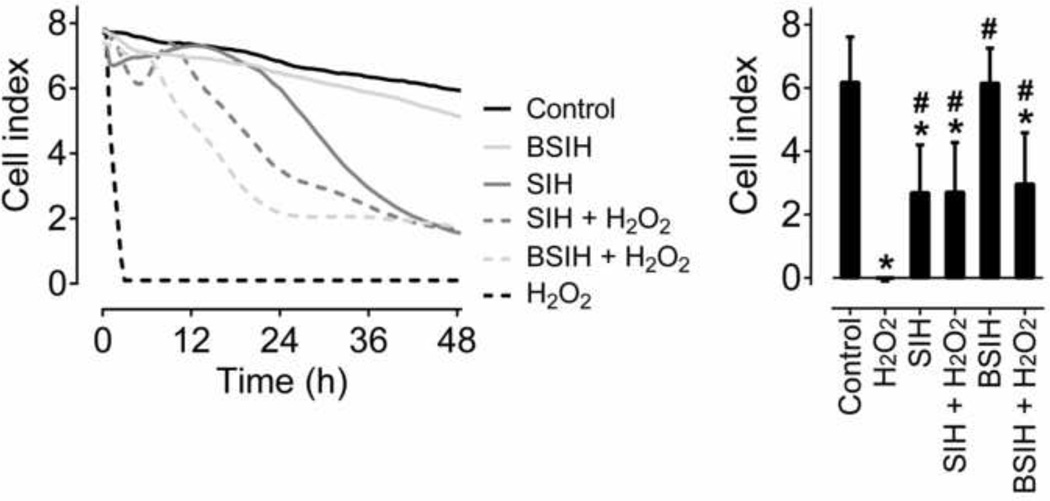

BSIH lacks inherent toxicity and promotes cardioprotection in primary culture of isolated rat cardiomyocytes

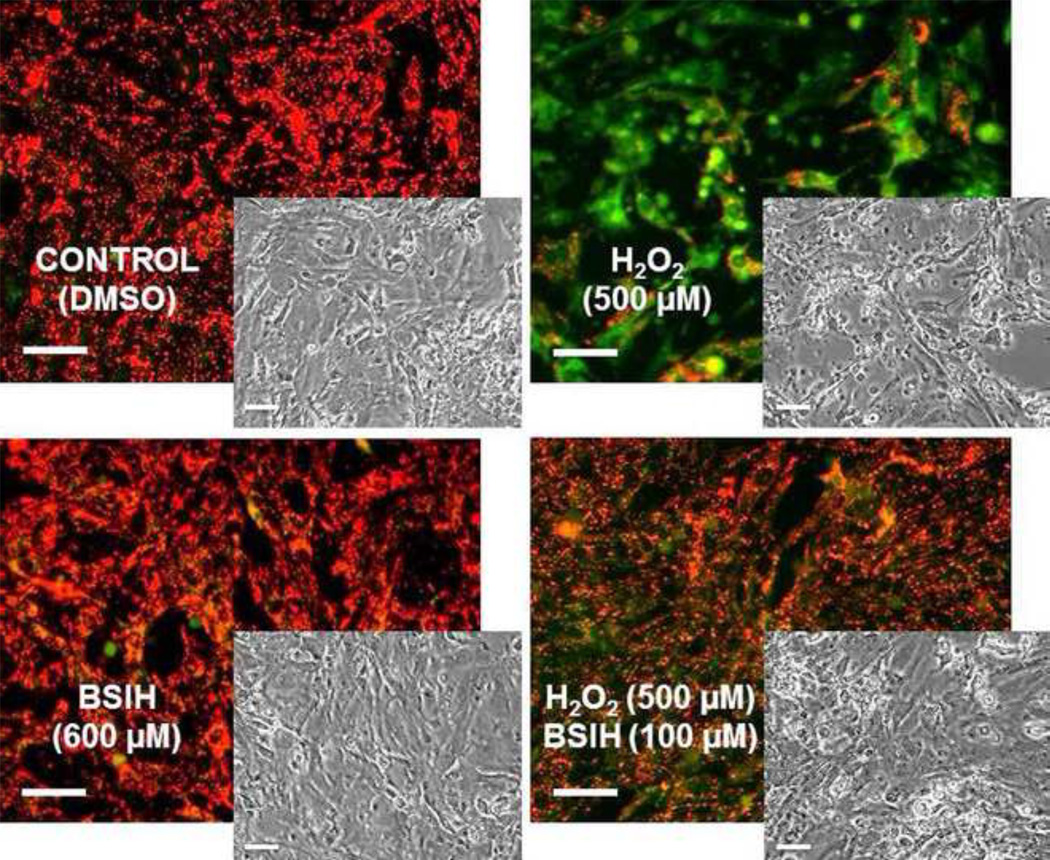

To confirm the key results of experiments performed with the H9c2 cell line, primary cultures of spontaneously beating isolated ventricular cardiomycytes from neonatal rats were used. As seen in Fig. 9, after 24-hour incubation of the cardiomyocytes with 600 µM BSIH (i.e., the highest achievable concentration), neither changes of cellular morphology, nor dissipation of ΔΨm could be observed. Furthermore, 100 µM BSIH was able to prevent the morphological changes and mitochondrial depolarization of cardiomyocytes induced by as high as 500 µM exogenous H2O2.

Figure 9. Evaluation of toxicity and cytoprotective properties of BSIH in primary culture of isolated ventricular cardiomyocytes from neonatal rats.

Cardiomyocytes were incubated with BSIH (600 µM) and with combination of BSIH (100 µM) and H2O2 (500 µM) for 24 h and then stained with JC1 probe for mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) visualization (darkfield epifluorescence images) and observed for changes in myocyte morphology (phase-contrast brightfield insert images). Scale bars represent 50 µm.

Discussion

Fe chelating agents including DFO, L1 and ICL670A have been successfully used in clinical practice for treatment of β-thalassemia major and other pathological states associated with Fe overload. Of note, the most important beneficial effect of Fe chelation therapy has been attributed to the prevention of cardiac mortality due to Fe-catalyzed and ROS-mediated cardiomyopathy [36–38]. Fe-mediated free radical injury is also attributed to cardiac myocyte apoptosis in other pathological conditions not associated with systemic Fe overload, such as ischemia/reperfusion injury, myocardium remodeling after myocardial infarction and heart failure [39–42]. This implicates that shielding cellular redox-active Fe should result in meaningful protection against oxidative stress.

In this study, H2O2 was used as a model to induce oxidative stress, as it is an intermediate in cellular ROS metabolism, being formed from spontaneous or enzyme-mediated superoxide dismutation and being reactive with Fe to generate toxic hydroxyl radicals. Apart from the rat embryonic cardiomyoblast-derived cell line H9c2, key results were also verified in primary cultures of spontaneously beating ventricular cardiomyocytes from neonatal rats. We chose the neutral red uptake assay to assess cell viability because it assesses the ability of viable cells to incorporate the supravital dye neutral red into lysosomes. As the organelles responsible for the degradation of most cellular metalloproteins, lysosomes are particularly vulnerable to oxidative stress and may burst due to intralysosomal Fenton-type reactions and associated peroxidative membrane destabilization [43]. Significant lysosomal rupture irreversibly commits the cell to death as released low mass Fe and lytic enzymes inflict secondary harm to other cellular constituents, including mitochondria [44], the key organelles regulating cellular death of cardiomyocytes [45]. In addition to gauging viability by cellular uptake of neutral red after 24 and 72 h incubation periods, we also determined lysosomal integrity 4 h after the exposure of H9c2 cells to 200 µM H2O2, which is the critical time-point of the H2O2-induced cytotoxicity as demonstrated by both cellular morphology observations and the real-time monitoring of cell viability using the label-free electric impedance measurements.

ICL670A was used in our experiments as a reference compound for its triazole derivative prochelators TRA-IMM and TIP. ICL670A is an orally-active chelator used in clinical practice. It has been shown to reduce cardiac Fe burden and attenuate myocardial oxidative stress [46]. A recent study demonstrated that ICL670A was able to significantly retard spontaneous catecholamine oxidation, block intracellular ROS formation and exert significant protection against the cellular toxicity of catecholamines and their oxidation products [17]. Our present study showed good chelating activity of this compound in buffered solution and in H9c2 cells. While 60 µM ICL670A significantly protected H9c2 cells against H2O2-induced damage, it also displayed considerable intrinsic toxicity, with slight - yet significant -cellular viability reduction observed even at 30 µM concentration.

SIH, the active agent of prochelators BSIH and BSIH-PD, belongs to the group of pyridoxal isonicotinoyl hydrazone analogs [13]. Because of its small size and favorable lipophilicity, SIH can be administered orally and readily enters cells to firmly chelate intracellular Fe. SIH has been shown to protect guinea pig or rat isolated cardiomyocytes, H9c2 cells and other cell types against damage induced by H2O2 [19, 47, 48] tert-butythydroperoxide [16] and catecholamine [18]. SIH has also been shown to protect against the cardiotoxicity of the anthracycline drug daunorubicin – both in vitro, using NVCM cells [49] and in vivo using a rabbit model [22]. Our current study confirmed its excellent chelating activity, which was comparable to that of ICL670A in HBS buffer and significantly better in H9c2 cells, results that correlate with our observations of better cytoprotective properties of SIH compared to ICL670A. SIH significantly protected H9c2 cells against H2O2-induced damage at concentrations down to 10 µM. Moreover, SIH was less toxic than ICL670A both during the 24 h and especially during 72 h incubations.

Our third tested chelator was HAPI, the novel methyl ketone derivative of SIH [26]. Our results demonstrated good chelating efficiency of HAPI in buffered solution and in cells. Its efficiency to protect H2O2-stressed H9c2 cells was comparable to SIH at concentrations of 30 µM and above. Inherent toxicity of HAPI was low after 24 h incubation but greatly increased after 72 h. We speculate that the greater cytotoxicity observed for HAPI and ICL670A compared to SIH at the longer exposure time may be due to differences in the stabilities of these structures. HAPI is significantly more resistant to plasma hydrolysis than SIH [26], and ICL670A is known to have a long plasma half-life [50]. Whereas the chelating efficiency of SIH self-destructs over time, the other agents could potentiate their toxicity by removing or withholding Fe from critical Fe-containing proteins, or otherwise interfering with normal metal metabolism [12].

To reduce the risk of unwanted toxicity due to Fe depletion, novel boronate-masked prochelators have been designed to avoid affecting metal homeostasis under physiological conditions. They do not bind metal ions until a protective mask is removed by H2O2 to reveal an effective chelating agent that can sequester di- and trivalent transition metal ions. While the tridentate chelators on which these prochelators have a thermodynamic binding preference for Fe(III), they can also bind other metal ions, including the biologically relevant Cu(II) and Zn(II) [27, 29]. These prochelators may represent a new approach in the treatment of pathological states induced by oxidative stress without systemic Fe overload [24]. The activation (demasking) is a critical property for the usefulness of potential cytoprotective prochelators, as the masking group is ideally unreactive with physiological ROS, yet can succumb to potentially harmful levels.

In the present study, five different prochelators were examined. Of the ICL670A prochelators, TRA-IMM showed almost no signs of activation in solution, while TIP showed feeble activation that was at least four-fold slower than BHAPI. Although TRA-IMM and TIP were both less toxic to H9c2 than ICL670A following long-term (72 h) exposure, after 24 h they induced greater viability reduction than their mother chelator, which is consistent with a previous study using ARPE-19 cells where TIP displayed greater inherent toxicity than ICL670A. Both TRA-IMM and TIP showed considerable potential to activate caspases, key mediators of cellular apoptosis. Whereas TIP has in this study displayed some tendency to ameliorate H2O2-induced injury, TRA-IMM displayed no cytoprotective potential at all.

BHAPI, the prochelator version of HAPI, has previously displayed promising protective potential on ARPE-19 cells exposed to H2O2 or the redox-active herbicide paraquat [29]. Interestingly, HAPI was generated from BHAPI upon cellular exposure to paraquat, but not when BHAPI was exposed to paraquat in cell-free systems, demonstrating that BHAPI can be activated intracellularly by endogenously-formed ROS (presumably H2O2) [29]. Our results demonstrated good H2O2-induced activation of BHAPI that reached almost 90 % of the chelating activity of its parent chelator in buffered solution and about 75 % in H9c2 cells. BHAPI significantly protected H9c2 cells against H2O2 stress in concentrations higher than 10 µM. It induced partial (≈ 50 %) protection with a maximum at 60 – 100 µM concentrations. BHAPI’s inherent acute toxicity was higher than that of HAPI at the 24 h time-point, but lower than that of ICL670A, TRA-IMM and particularly TIP.

Promising protective properties of BSIH against H2O2-induced damage have been previously described on ARPE-19 cells [24]. Here we observed good chelating activity of BSIH in solution after activation by H2O2 in both calcein fluorescence assays. BSIH-PD, the other prochelator derived from SIH, showed similar chelating activity in buffered solution as BSIH, but lower intracellular activation of Fe chelation activity, which correlated with its slightly lower cellular protective effect. BSIH significantly protected H9c2 cells against H2O2-induced damage at concentrations higher than the effective levels of SIH (the lowest effective concentration of BSIH was 60 µM vs. 10 µM in SIH), but at higher concentrations its protection was comparable or better than SIH. BSIH also significantly protected H9c2 cells against damage caused by several other known pro-oxidant xenobiotics: tert-butyl hydroperoxide, redox-cycling herbicide paraquat, synthetic catecholamine isoprenaline and cardiotoxic anthracycline anticancer agent doxorubicin.

The unique feature of BSIH is its exceptionally low toxicity. The inherent toxicity of BSIH-PD was second best, only after BSIH. At its highest achievable concentration of 600 µM, BSIH did not induce any significant viability reduction on H9c2 cells following 24 and 72 h incubations and even after a week-long (168 h) cellular exposure, only very low toxicity was noticed (insignificant viability reduction to 92 % of control values). Protective efficiency against H2O2 and negligible inherent cytotoxicity of BSIH was verified in isolated primary rat cardiomyocytes and HaCaT keratinocyte cells, with only slight toxicity on 3T3 fibroblast, HepG2 and PC12 cells, which was always lower than in the case of the parent chelator SIH.

While the poor hydrolytic stability of SIH is a drawback during the “waiting” for oxidative stress, this disadvantage has been elegantly overcome by BSIH, which is considerably more resistant against degradation [24]. After activation of BSIH to SIH and subsequent loading with Fe, residual uncomplexed SIH is likely to hydrolyze into salicylaldehyde and isoniazide (an antituberculotic drug with a favorable safety profile). This self-destructive activity may be an advantage, since more stable chelators tend to be cytotoxic. Indeed, SIH has previously shown the best “therapeutic” ratio of inherent toxicity and cytoprotective efficiency against diverse ROS-mediated injuries (H2O2, tert-butyl hydroperoxide, catecholamines and their oxidation products) when compared with other Fe chelators, including the clinically-approved agents DFO, ICL670A or L1 [16, 17]. Of note, SIH has a very favorable in vivo toxicological profile, as it was well tolerated and induced no histopathological signs of organ toxicity or changes of biochemical and hematological parameters following its 10-week repeated administration to rabbits [51].

The results of the present study therefore unambiguously identify BSIH as the single best candidate for further investigations of its: (i) in vivo pharmacokinetics profile, (ii) pharmacodynamics in more complex animal models of cardiovascular (and other) diseases with a known or presumed component of oxidative stress, and, (iii) in vivo safety pharmacological profile for potential undesirable pharmacodynamic effects (in relation to dosage within and above the substance's therapeutic range) to assess whether the exceptionally low toxicity of BSIH in cell lines and isolated cardiomyocytes also translates to whole animal conditions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mrs. Alena Pakostová for her technical assistance in the cell-culture laboratory. This study was supported by the Charles University in Prague (grants GAUK 367911 and SVV 267 004), Czech Science Foundation (grant 13-15008S) and the European Social Fund and the State Budget of the Czech Republic (Operational Program CZ.1.07/2.3.00/30.0061). K.J.F. gratefully acknowledges funding from the US National Institutes of Health (grant GM084176).

Abbreviations

- BHAPI

(E)-N´-(1-(2-((4-(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,2,3-dioxoborolan-2-yl)benzyl)oxy)phenyl)ethylidene) isonicotinohydrazide

- BSIH

(E)-N´-[2-(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-[1,2,3]dioxaborolan-2-yl)-benzylidene] isonicotinohydrazide ;BSIH-PD, (E)-N´-[2-(3a,5,5-trimethylhexahydro-4,6-methanobenzo[d][1,2,3]dioxaborolan-2-yl)benzylidene] isonicotinohydrazide

- DFO

desferrioxamine

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- FAC

ferric ammonium citrate

- FAS

ferrous diammonium sulphate

- HAPI

(E)-N´-[1-(2-hydroxyphenyl)ethyliden] isonicotinohydrazide

- ICL670A

4-[(3Z,5E)-3,5-bis(6-oxo-1-cyclohexa-2,4-dienylidene)-1,2,4-trizolidin-1-yl] benzoic acid

- L1

deferiprone

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SIH

(E)-N´-(2-hydroxybezylidene) isonicotinohydrazide

- tBHP

tert-butyl hydroperoxide

- TIP

4-(5-(2-((4-boronobenzyl)oxy)phenyl)-3-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-1H-1,2,4-triazol-1-yl)benzoic acid

- TRA-IMM

methyl-4-(3-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-5-(2-((4-(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,2,3-dioxoborolan-2-yl)benzyl)oxy)phenyl)-1H-1,2,4-triazol-1-yl) benzoate

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Andrews NC, Schmidt PJ. Iron homeostasis. Annu Rev Physiol. 2007;69:69–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.031905.164337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halliwell B, Gutteridge JMC. Free radicals in biology and medicine. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jomova K, Valko M. Advances in metal-induced oxidative stress and human disease. Toxicology. 2011;283:65–87. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kell DB. Towards a unifying, systems biology understanding of large-scale cellular death and destruction caused by poorly liganded iron: Parkinson's, Huntington's, Alzheimer's, prions, bactericides, chemical toxicology and others as examples. Arch Toxicol. 2010;84:825–889. doi: 10.1007/s00204-010-0577-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mladenka P, Simunek T, Hubl M, Hrdina R. The role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in cellular iron metabolism. Free Radic Res. 2006;40:263–272. doi: 10.1080/10715760500511484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reif DW. Ferritin as a source of iron for oxidative damage. Free Radic Biol Med. 1992;12:417–427. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(92)90091-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Terman A, Brunk UT. Oxidative stress, accumulation of biological 'garbage', and aging. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:197–204. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Griendling KK, FitzGerald GA. Oxidative stress and cardiovascular injury: Part I: basic mechanisms and in vivo monitoring of ROS. Circulation. 2003;108:1912–1916. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000093660.86242.BB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hennekens CH, Buring JE, Manson JE, Stampfer M, Rosner B, Cook NR, Belanger C, LaMotte F, Gaziano JM, Ridker PM, Willett W, Peto R. Lack of effect of long-term supplementation with beta carotene on the incidence of malignant neoplasms and cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1145–1149. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605023341801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee R, Margaritis M, Channon KM, Antoniades C. Evaluating oxidative stress in human cardiovascular disease: methodological aspects and considerations. Curr Med Chem. 2012;19:2504–2520. doi: 10.2174/092986712800493057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franz KJ. Clawing back: broadening the notion of metal chelators in medicine. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2013;17:143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galey JB. Recent advances in the design of iron chelators against oxidative damage. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2001;1:233–242. doi: 10.2174/1389557013406846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalinowski DS, Richardson DR. The evolution of iron chelators for the treatment of iron overload disease and cancer. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57:547–583. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.4.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dobsak P, Siegelova J, Wolf JE, Rochette L, Eicher JC, Vasku J, Kuchtickova S, Horky M. Prevention of apoptosis by deferoxamine during 4 hours of cold cardioplegia and reperfusion: in vitro study of isolated working rat heart model. Pathophysiology. 2002;9:27. doi: 10.1016/s0928-4680(02)00054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan W, Taylor AJ, Ellims AH, Lefkovits L, Wong C, Kingwell BA, Natoli A, Croft KD, Mori T, Kaye DM, Dart AM, Duffy SJ. Effect of iron chelation on myocardial infarct size and oxidative stress in ST-elevation-myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:270–278. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.111.966226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bendova P, Mackova E, Haskova P, Vavrova A, Jirkovsky E, Sterba M, Popelova O, Kalinowski DS, Kovarikova P, Vavrova K, Richardson DR, Simunek T. Comparison of clinically used and experimental iron chelators for protection against oxidative stress-induced cellular injury. Chem Res Toxicol. 2010;23:1105–1114. doi: 10.1021/tx100125t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haskova P, Koubkova L, Vavrova A, Mackova E, Hruskova K, Kovarikova P, Vavrova K, Simunek T. Comparison of various iron chelators used in clinical practice as protecting agents against catecholamine-induced oxidative injury and cardiotoxicity. Toxicology. 2011;289:122–131. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haskova P, Kovarikova P, Koubkova L, Vavrova A, Mackova E, Simunek T. Iron chelation with salicylaldehyde isonicotinoyl hydrazone protects against catecholamine autoxidation and cardiotoxicity. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50:537–549. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horackova M, Ponka P, Byczko Z. The antioxidant effects of a novel iron chelator salicylaldehyde isonicotinoyl hydrazone in the prevention of H(2)O(2) injury in adult cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;47:529–536. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simunek T, Boer C, Bouwman RA, Vlasblom R, Versteilen AM, Sterba M, Gersl V, Hrdina R, Ponka P, de Lange JJ, Paulus WJ, Musters RJ. SIH--a novel lipophilic iron chelator--protects H9c2 cardiomyoblasts from oxidative stress-induced mitochondrial injury and cell death. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;39:345–354. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simunek T, Sterba M, Popelova O, Adamcova M, Hrdina R, Gersl V. Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity: overview of studies examining the roles of oxidative stress and free cellular iron. Pharmacol Rep. 2009;61:154–171. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(09)70018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sterba M, Popelová O, Simůnek T, Mazurová Y, Potácová A, Adamcová M, Guncová I, Kaiserová H, Palicka V, Ponka P, Gersl V. Iron chelation-afforded cardioprotection against chronic anthracycline cardiotoxicity: a study of salicylaldehyde isonicotinoyl hydrazone (SIH) Toxicology. 2007;235:150–166. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Charkoudian LK, Pham DM, Franz KJ. A pro-chelator triggered by hydrogen peroxide inhibits iron-promoted hydroxyl radical formation. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:12424–12425. doi: 10.1021/ja064806w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Charkoudian LK, Dentchev T, Lukinova N, Wolkow N, Dunaief JL, Franz KJ. Iron prochelator BSIH protects retinal pigment epithelial cells against cell death induced by hydrogen peroxide. J Inorg Biochem. 2008;102:2130–2135. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Charkoudian LK, Pham DM, Kwon AM, Vangeloff AD, Franz KJ. Modifications of boronic ester pro-chelators triggered by hydrogen peroxide tune reactivity to inhibit metal-promoted oxidative stress. Dalton Trans. 2007:5031–5042. doi: 10.1039/b705199a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hruskova K, Kovarikova P, Bendova P, Haskova P, Mackova E, Stariat J, Vavrova A, Vavrova K, Simunek T. Synthesis and initial in vitro evaluations of novel antioxidant aroylhydrazone iron chelators with increased stability against plasma hydrolysis. Chem Res Toxicol. 2011;24:290–302. doi: 10.1021/tx100359t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kielar F, Wang Q, Boyle PD, Franz KJ. A boronate prochelator built on a triazole framework for peroxide-triggered tridentate metal binding. Inorganica Chim Acta. 2012;393:294–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ica.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edward JT, Gauthier M, Chubb FL, Ponka P. Synthesis of new acylhydrazones as iron-chelating compounds. J. Chem. Eng. Data. 1988:538–540. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kielar F, Helsel ME, Wang Q, Franz KJ. Prochelator BHAPI protects cells against paraquat-induced damage by ROS-triggered iron chelation. Metallomics. 2012;4:899–909. doi: 10.1039/c2mt20069d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kimes BW, Brandt BL. Properties of a clonal muscle cell line from rat heart. Exp Cell Res. 1976;98:367–381. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(76)90447-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Espósito BP, Epsztejn S, Breuer W, Cabantchik ZI. A review of fluorescence methods for assessing labile iron in cells and biological fluids. Anal Biochem. 2002;304:1–18. doi: 10.1006/abio.2002.5611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glickstein H, El RB, Link G, Breuer W, Konijn AM, Hershko C, Nick H, Cabantchik ZI. Action of chelators in iron-loaded cardiac cells: Accessibility to intracellular labile iron and functional consequences. Blood. 2006;108:3195–3203. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-020867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Repetto G, del Peso A, Zurita JL. Neutral red uptake assay for the estimation of cell viability/cytotoxicity. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1125–1131. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ke N, Wang X, Xu X, Abassi YA. The xCELLigence system for real-time and label-free monitoring of cell viability. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;740:33–43. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-108-6_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brunk UT, Neuzil J, Eaton JW. Lysosomal involvement in apoptosis. Redox Rep. 2001;6:91–97. doi: 10.1179/135100001101536094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berdoukas V, Nord A, Carson S, Puliyel M, Hofstra T, Wood J, Coates TD. Tissue iron evaluation in chronically transfused children shows significant levels of iron loading at a very young age. Am J Hematol. 2013 doi: 10.1002/ajh.23543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hershko C, Link G, Konijn AM, Cabantchik ZI. Objectives and mechanism of iron chelation therapy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1054:124–135. doi: 10.1196/annals.1345.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nienhuis AW, Nathan DG. Pathophysiology and Clinical Manifestations of the beta-Thalassemias. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2:a011726. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a011726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheng Y, Liu X, Zhang S, Lin Y, Yang J, Zhang C. MicroRNA-21 protects against the H(2)O(2)-induced injury on cardiac myocytes via its target gene PDCD4. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;47:5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Han SY, Li HX, Ma X, Zhang K, Ma ZZ, Tu PF. Protective effects of purified safflower extract on myocardial ischemia in vivo and in vitro. Phytomedicine. 2009;16:694–702. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2009.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luo X, Cai H, Ni J, Bhindi R, Lowe HC, Chesterman CN, Khachigian LM. c-Jun DNAzymes inhibit myocardial inflammation, ROS generation, infarct size, and improve cardiac function after ischemia-reperfusion injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:1836–1842. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.189753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mishra PK, Tyagi N, Sen U, Givvimani S, Tyagi SC. H2S ameliorates oxidative and proteolytic stresses and protects the heart against adverse remodeling in chronic heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H451–H456. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00682.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Terman A, Kurz T, Gustafsson B, Brunk UT. The involvement of lysosomes in myocardial aging and disease. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2008;4:107–115. doi: 10.2174/157340308784245801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roberg K. Relocalization of cathepsin D and cytochrome c early in apoptosis revealed by immunoelectron microscopy. Lab Invest. 2001;81:149–158. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Trojel-Hansen C, Kroemer G. Mitochondrial control of cellular life, stress, and death. Circ Res. 2012;111:1198–1207. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.268946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Al-Rousan RM, Paturi S, Laurino JP, Kakarla SK, Gutta AK, Walker EM, Blough ER. Deferasirox removes cardiac iron and attenuates oxidative stress in the iron-overloaded gerbil. Am J Hematol. 2009;84:565–570. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kurz T, Gustafsson B, Brunk UT. Intralysosomal iron chelation protects against oxidative stress-induced cellular damage. FEBS J. 2006;273:3106–3117. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lukinova N, Iacovelli J, Dentchev T, Wolkow N, Hunter A, Amado D, Ying GS, Sparrow JR, Dunaief JL. Iron chelation protects the retinal pigment epithelial cell line ARPE-19 against cell death triggered by diverse stimuli. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:1440–1447. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Simůnek T, Sterba M, Popelová O, Kaiserová H, Adamcová M, Hroch M, Hasková P, Ponka P, Gersl V. Anthracycline toxicity to cardiomyocytes or cancer cells is differently affected by iron chelation with salicylaldehyde isonicotinoyl hydrazone. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;155:138–148. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Galanello R, Piga A, Alberti D, Rouan MC, Bigler H, Sechaud R. Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of ICL670, a new orally active iron-chelating agent in patients with transfusion-dependent iron overload due to beta-thalassemia. J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;43:565–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Klimtova I, Simunek T, Mazurova Y, Kaplanova J, Sterba M, Hrdina R, Gersl V, Adamcova M, Ponka P. A study of potential toxic effects after repeated 10-week administration of a new iron chelator--salicylaldehyde isonicotinoyl hydrazone (SIH) to rabbits. Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove) 2003;46:163–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.