Abstract

We present the synthesis and characterization of octaarginine-conjugated Copper-Gad-2 (Arg8CG2), a new copper-responsive magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agent that combines a Gd3+-DO3A scaffold with a thioether-rich receptor for copper recognition. The inclusion of a polyarginine appendage leads to a marked increase in cellular uptake compared to previously reported MRI-based copper sensors of the CG family. Arg8CG2 exhibits a 220% increase in relaxivity (r1 = 3.9 to 12.5 mM−1 s−1) upon 1 : 1 binding with Cu+, with a highly selective response to Cu+ over other biologically relevant metal ions. Moreover, Arg8CG2 accumulates in cells at nine-fold greater concentrations than the parent CG2 lacking the polyarginine functionality and is retained well in the cell after washing. In cellulo relaxivity measurements and T1-weighted phantom images using a Menkes disease model cell line demonstrate the utility of Arg8CG2 to report on biological perturbations of exchangeable copper pools.

Introduction

Copper is an essential element for life, acting as a cofactor in a number of important enzymes that govern redox processes within the body.1 On the other hand, genetic disorders such as Wilson’s and Menkes diseases arise from mutations in copper handling proteins, and disruption of copper homeostasis is associated with a number of neurodegenerative pathologies including Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and prion diseases. A number of fluorescent sensors have been developed to enable visualization of biological copper pools, based on nucleic acids,2,3 proteins,4,5 and small-molecule fluorophores.6–13 Gaining a better understanding of how copper contributes to healthy and disease states, however, requires the development of methods for imaging copper distribution in the whole body rather than in cultured cells or tissue samples. To this end, X-ray fluorescence microscopy,14,15 positron emission tomography (PET),16,17 and near infrared imaging18 have been used to study copper distribution in tissue and animal models of copper mishandling.

Our laboratory has been interested in the application of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for studying copper biology, as this technique is a powerful imaging modality in which whole body images of live specimens can be obtained at high resolution without the use of ionizing radiation.19,20 The observed contrast in MR images can be increased by the use of contrast agents containing paramagnetic ions. Gd3+ (S = 7/2) is most commonly employed for this purpose, owing to its large number of unpaired electrons and its ability to increase the proton relaxation rate of water molecules interacting with the metal center. A number of elegant responsive MR contrast agents have been developed,21,22 in which a relaxivity change can report on pH,23,24 gene expression,25 enzyme activity,26–28 or metal ion concentration.22,29–32 Notably, a number of recent studies have reported MR-based probes that respond to Cu2+.33–36 We are also interested in studying Cu+, which is the primary copper species in the reducing intracellular environment. We have previously developed a series of MR-based probes that exhibit increases in longitudinal relaxivity (r1) in response to Cu+ and/or Cu2+.36–38 Of particular note is CG2, a Cu+-sensitive contrast agent that displays a 360% increase in r1 upon addition of one equivalent of Cu+ (r1 = 1.5 to 6.9 mM−1 s−1; Scheme 1).22,38

Scheme 1.

Copper-Gad contrast agent, CG2.

Despite the promising in vitro behaviour of the many metal-responsive Gd-based contrast agents,22,39 their ability to image changes in metal concentration in cellulo remains insufficiently explored. Previous biological, MR-based metal ion sensing has largely focused on Zn physiology, including elegant studies by Sherry and co-workers on the use of a Gd-based zinc sensor for the in vivo detection of extracellular zinc released by pancreatic beta cells31 and Lippard, Jasanoff, and colleagues on the application of a cell-permeable Mn-based contrast agent to sense zinc levels in vivo.30,40 Encouraged by the large dynamic range of CG2, we sought to exploit its properties in the design of an MR contrast agent for the imaging of Cu+ in living systems. The +1 oxidation state of copper dominates in intracellular spaces; we expected that CG2, like other typical Gd3+-containing MR contrast agents such as Gd-DTPA and Gd-DOTA, would be largely confined to the extracellular space due to a poor ability to cross cellular membranes.41 We therefore considered various strategies to elicit enhanced cellular uptake, which include electroporation,42 encapsulation into liposomes43,44 and conjugation to various macromolecules such as peptides,45–48 dendrimers,49 dextrans,50 and TiO251 or gold52 nanoparticles, and settled on the use of a polyarginine tag as a promising method to this end.53–56 In this context, Weissleder and coworkers have exploited the TAT peptide sequence from the HIV virus to render nanoparticle-based MR contrast agents cell-permeable,57–59 and Meade and coworkers have reported modified Gd3+-DTPA and Gd3+-DOTA complexes containing octaarginine (Arg8) tails.41,45,51 For the latter, cellular uptake of these complexes was confirmed by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrosmetry and X-ray fluorescence techniques. Based on these precedents, we reasoned that appending an Arg8 tag onto our CG2 scaffold should readily deliver our Cu+-responsive agent to the interior of the cell. In this edge article, we now report the design and synthesis of Arg8CG2, and our comparisons of the cellular behaviour of this complex to the parent CG2. We then detail our studies of a murine cell line bearing a mutant form of the copper efflux protein, ATP7A, using Arg8CG2, demonstrating that this molecular imaging agent can distinguish between normal and aberrant labile copper pools in a disease model, and reporting the in cellulo application of a metal-responsive Gd-based MR contrast agent.

Results and discussion

Design and synthesis of a Gd contrast agent bearing a polyarginine tail

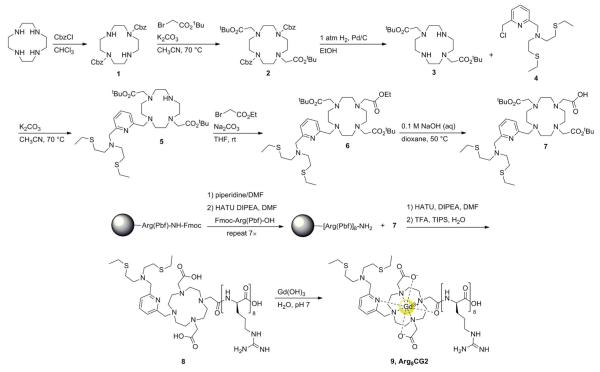

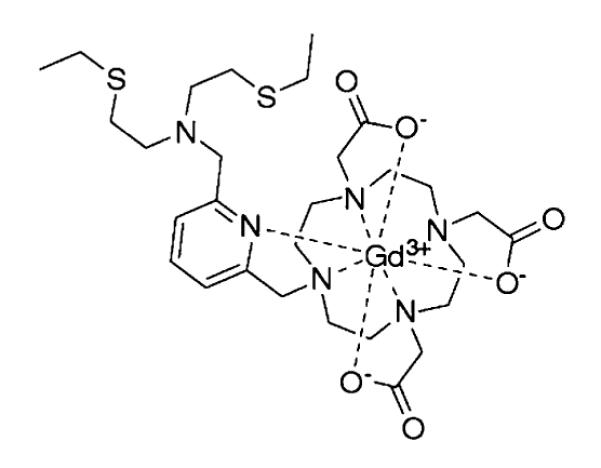

The synthesis of Arg8CG2 is detailed in Scheme 2. Bis-protected cyclen 1 was synthesized by a previously-reported literature procedure in quantitative yield.60 Alkylation of 1 with tert-butyl bromoacetate furnished compound 2. The benzyl carbamate protecting groups were removed by hydrogenation over Pd/C to yield 3 in nearly quantitative yield. The trisubstituted cyclen 5 was prepared by slow addition of electrophile 438 to a heated mixture of 3 and K2CO3. By this method, compound 5 was produced in 42% yield, with the tetrasubstituted by-product also observed. Triester 6 was obtained by alkylation of 5 with ethyl bromoacetate at room temperature in THF. The mono-carboxylate 7 was formed by the selective deprotection of the ethyl ester in 0.1 M NaOH in a water–dioxane (1 : 3) mixture at 50 °C. Arg8-functionalized Wang resin was obtained using standard solid phase peptide synthesis techniques. Coupling of 7 to the resin-bound polyarginine using HATU and DIPEA in DMF, followed by cleavage from the resin using TFA, gave ligand 8 following HPLC purification. Metalation of 8 was achieved with a slight excess of Gd(OH)3 in H2O (pH 6), followed by purification via reversed-phase chromatography using a C18 SepPak cartridge.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Arg8CG2.

Spectroscopic properties and response to Cu+

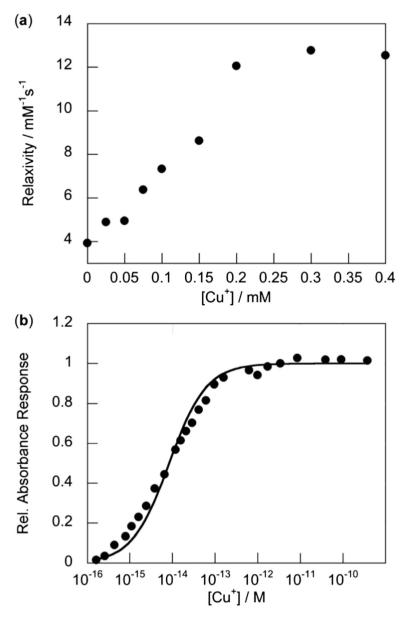

The relaxivity properties of Arg8CG2 were characterized in phosphate buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) at 37 °C and Gd3+ concentrations were determined by ICP-OES. In the absence of Cu+, the relaxivity of Arg8CG2 is 3.9 mM−1 s−1 (Fig. S1†). This r1 is significantly higher than that of the parent complex CG2 (r1 = 1.5 mM−1 s−1), which is likely to reflect an increased rotational correlation time (τR) due to the large octaarginine group, and increased second-sphere hydration due to the presence of additional hydrogen-bonding groups from the arginine residues. Upon addition of Cu+, the r1 of Arg8CG2 increases to 12.5 mM−1 s−1, a 220% increase in relaxivity (Δr1 = 8.6 mM−1 s−1; Fig. 1a). Although the observed turn-on response is a smaller percent increase in r1 than for our original CG2 platform (360%), this value is competent for in vivo applications. We note that the presence of the polyarginine tail does not appear to greatly affect the ability of our platform to respond to Cu+ ions.

Fig. 1.

Interaction of Arg8CG2 with Cu+. (a) Plot of r1 relaxivity versus added Cu+ for a 0.2 mM solution of Arg8CG2 in PBS (pH 7.4), at 37 °C at a proton Larmor frequency of 60 MHz. (b) Normalized absorbance response of 0.2 mM Arg8CG2 to buffered Cu+ solutions for determination of the apparent Kd value. Spectra were acquired in PBS (pH 7.4) at 25 °C. The black trace represents the best fit (Kd = 8.3 × 10−15 M, R2 = 0.986).

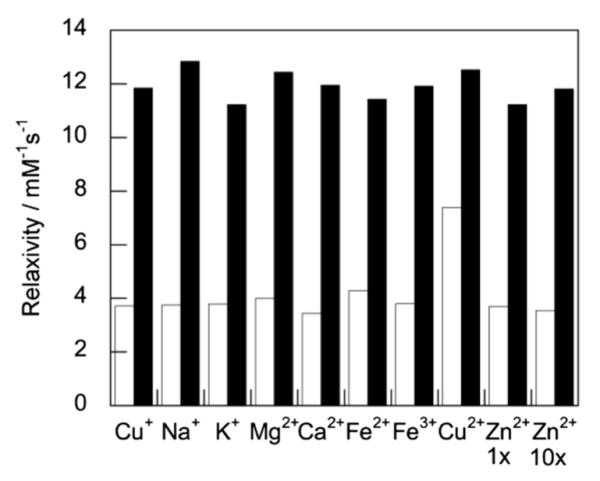

Since our polyarginine-functionalized Gd3+ complex responds to Cu+, we sought to characterize the binding interaction between Arg8CG2 and Cu+. A Job plot analysis confirms a 1 : 1 Arg8CG2/Cu+ binding stoichiometry (Fig. S2†). The binding affinity of our complex for Cu+ was determined by monitoring changes in the absorbance spectrum of the Arg8CG2–Cu+ complex in the presence of varying amounts of thiourea, which is known to be a competitive ligand for Cu+.61 Analysis of the resulting data gave an apparent Kd of 8.3 × 10−15 M (Fig. 1b), signifying even tighter binding than the parent CG2 complex (Kd = 2.6 × 10−13 M). Moreover, the presence of the polycationic tail on the Gd core does not affect the metal ion selectivity of the CG2-based scaffold (Fig. 2). Arg8CG2 selectivity responds to Cu+ over a range of biologically relevant metal ions including 10 mM Na+, 2 mM K+, Mg2+, and Ca2+, 0.2 mM Fe2+, Fe3+, and Cu2+, and Zn2+ at both 0.2 mM and 2 mM concentrations. Arg8CG2 does have some response to Cu2+, but we do not anticipate this behavior to be a drawback for the in cellulo use of Arg8CG2, since the reducing environment of the cell favors Cu+ over Cu2+. Phantom MR images of Arg8CG2 in PBS showed that the probe displays different levels of contrast in samples with and without added Cu+ at clinically-relevant field strengths (Fig. S3†).

Fig. 2.

Relaxivity responses of Arg8CG2 to various metal ions. White bars represent the addition of the appropriate metal ion (10 mM for Na+; 2 mM for K+, Mg2+, and Ca2+; 0.2 mM for Fe2+, Fe3+ and Cu2+) to 0.2 mM Arg8CG2. Response to Zn2+ was measured both at 0.2 mM Zn2+ (Zn2+ 1 ×) and 2 mM Zn2+ (Zn2+ 10 ×). Black bars represent the subsequent addition of 0.2 mM Cu+ to the contrast agent solution. Relaxivity measurements were acquired at 37 °C in PBS (pH 7.4) at a proton Larmor frequency of 60 MHz.

Arg8CG2 exhibits greater cellular uptake and in cellulo relaxivity than CG2

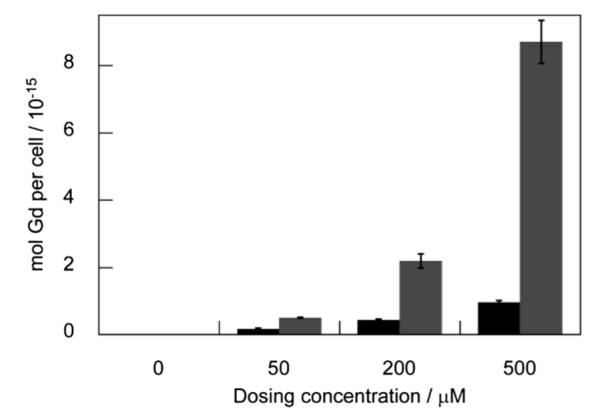

We anticipated that the polyarginine tail would afford Arg8CG2 much greater cellular uptake compared to the parent complex, CG2. This behavior was tested using HEK 293T as a model cell line. Cells were treated for one hour with either of the complexes at a range of concentrations, washed with PBS, lysed and digested prior to the determination of Gd content by ICP-MS. For each sample, protein content was also determined using a BCA assay and Gd uptake per cell was determined by calibration of the BCA assay to total cell number. These results show a ten-fold greater uptake of Arg8CG2 than CG2 at a dosing concentration of 500 μM (Fig. 3), confirming that the octaarginine tail contributes to better transport across the cell membrane. Notably, the calculated number of complexes per cell is within the range of values observed by Allen et al. for their series of polyarginine-containing complexes.41 An analysis of the uptake of Arg8CG2 after 1 h and 15 h indicates greater cellular uptake after the shorter time period (Fig. S4†), which may be due to cellular clearance mechanisms. This observation is consistent with the findings of a broad-scale study of cell-penetrating peptides, which reported that maximal uptake was achieved between 30 min and 2 h.62 On the basis of these results, all subsequent experiments were performed with an incubation time of 1 h and a dosing concentration of 500 μM.

Fig. 3.

Cellular uptake of complexes in HEK 293T cells. (a) CG2 (black) and Arg8CG2 (gray) in HEK 293T cells following 1 h incubation at various dosing concentrations. After incubation, cells were rinsed with PBS, lysed with RIPA buffer, dissolved in nitric acid and analyzed by ICP–MS. Error bars represent one standard deviation (n = 4).

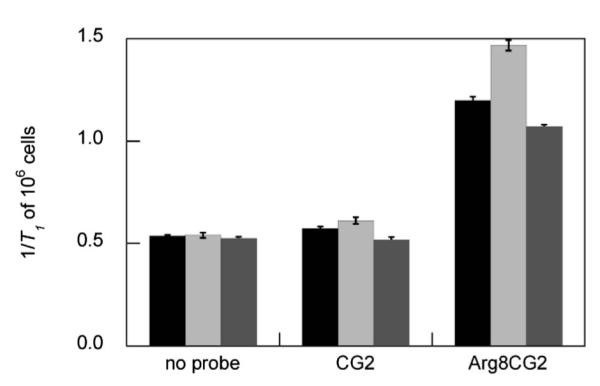

Having established the superior cellular uptake of Arg8CG2, we then sought to investigate whether this difference translated into a change in in cellulo relaxivity. We pretreated HEK cells with CuCl2 or bathocuproine disulfonate (BCS), a membrane-impermeable copper chelator, which is commonly used to globally deplete intracellular copper. After washing, we then treated the cells with 500 μM CG2 or Arg8CG2 for 1 h. The cells were again washed, trypsinized, pelleted, resuspended in PBS, and immediately placed in a relaxometer tube, in which the T1 was measured. Cu-treated cells incubated with CG2 exhibited a relaxivity that was significantly higher than control cells (p < 0.05, Fig. 4), confirming that the probe is able to detect increases in the cellular copper pool. On the other hand, BCS-treated cells, in which there is a global depletion of labile copper, exhibited a significantly lower relaxivity, showing that CG2 is sensitive to basal levels of copper and can detect depletions in this pool. The relaxivity values obtained for this pool, however, were not much greater than those measured for cells alone, in the absence of probe. Cells treated with Arg8CG2, on the other hand, exhibited markedly higher relaxivities than those cells with no probe, and while they showed the same trends as CG2 for Cu- and BCS-treated cells, these differences were much more pronounced. The collective results in the model HEK 293T cell line indicate that, compared to CG2, Arg8CG2 exhibits in cellulo relaxivities that are much more suitable for the study of perturbations in labile cellular Cu levels.

Fig. 4.

1/T1 values of HEK 293T cells treated with 500 mM CG2 or Arg8CG2 following incubation with vehicle control (black), copper (light gray, 100 μM, 48 h) or BCS (dark gray, 200 μM, 48 h). Relaxivity measurements were acquired at 37 °C in PBS (pH 7.4) at a proton Larmor frequency of 60 MHz. Error bars represent one standard deviation (n = 3) and statistical analyses were performed with a two-tailed Student’s t-test relative to the control. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01.

Arg8CG2 can report on labile copper pools in a disease model

Since Arg8CG2 can report on basal labile copper levels, and on increases and decreases in this pool, we sought to apply this probe to study the effects of mutations in the Atp7a gene on intracellular copper availability. This gene encodes the copper-transporting ATPase 1, ATP7A, which is the major copper efflux protein, and is therefore essential in the maintenance of cellular Cu homeostasis.63 In humans, mutations in the X-linked Atp7a gene are responsible for Menkes syndrome. On a cellular level, mutations in Atp7a give rise to elevated copper levels, exacerbated in cases of Cu supplementation.12,64 To investigate whether our probe could detect differences between healthy and disease states, we used the Menkes model WG1005 fibroblast line, which bears mutations in Atp7a, in comparison to control fibroblasts, MCH58, which express wild-type Atp7a.12

We initially sought to evaluate the toxicity of our two Gd complexes in the fibroblast cell lines, as well as in HEK 293T cells, by using the WST-1 assay (Table 1). No appreciable toxicity for CG2 was observed in any cell line at concentrations up to 2 mM over a 24 h period. Arg8CG2, on the other hand, decreased cellular viability over 24 h in the three cell lines, particularly HEK 293T and WG1005. This observation is consistent with reports of the toxicity of octaarginine-bearing compounds.62 The results of the 4 h incubations, however, demonstrate much better tolerance for the complex, and indicate that our dosing conditions of 500 μM for 1 h are unlikely to elicit significant cell death.

Table 1.

Cellular toxicities (IC50) for complexesa

| CG2 IC50/μM |

Arg8CG2 IC50/μM |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 h | 24 h | 4 h | 24 h | |

| HEK | >2000 | >2000 | >2000 | 295 (23) |

| MCH58 | >2000 | >2000 | 1864 (19) | 1153 (58) |

| WG1005 | >2000 | >2000 | 1517 (41) | 499 (18) |

Values represent the mean of triplicate readings of at least 3 independent measurements, with standard deviations in parentheses.

Uptake studies show a 9-fold greater accumulation of Arg8CG2 than CG2 in both cell lines, with similar intracellular Gd concentrations measured to those observed for HEK cells (Fig. S5†). Egress studies were also performed in these cell lines; following 1 h incubation with complex, the medium was removed, and replaced with fresh medium for 30 min, after which time intracellular Gd concentrations were measured. These results show that Arg8CG2 is retained very well, with a greater than 80% retention in both cell lines, while only 20% of CG2 is retained in the cell. These data provide further support for the use of a polyarginine tag for an in cellulo probe. Since all in cellulo relaxivity and phantom imaging studies reported here were performed within 30 min of cell collection, we can be confident that the localization of Arg8CG2 is primarily intracellular.

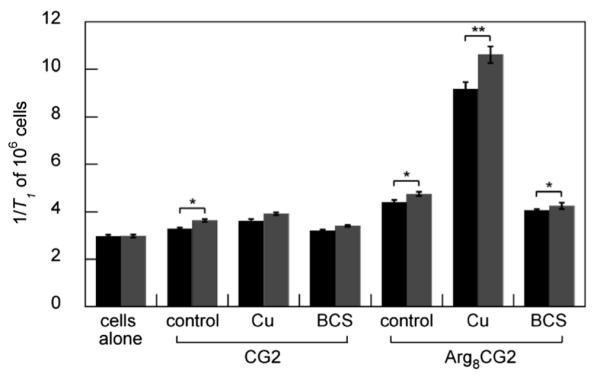

The 1/T1 values of the two cell lines upon treatment with CG2 and Arg8CG2 are shown in Fig. 5. As observed for the HEK 293T cells, there is a significant increase in 1/T1 for cells treated with Cu and then Arg8CG2, and a significant decrease for cells treated with BCS, compared to control and copper-treated cells. Notably, there is a significantly higher relaxivity, corresponding to a higher copper concentration, for the WG1005 cell line than for MCH58 cells. This observation is consistent with a mutation in Atp7a perturbing the ability of the cell to excrete copper. The same trend can also be observed for CG2-treated cells, although only the control cells exhibit a statistically significant difference in relaxivity, highlighting the superiority of Arg8CG2 for the in cellulo assessment of labile copper levels.

Fig. 5.

1/T1 values of MCH58 (black) and WG1005 (gray) cells treated with 500 μM CG2 (left) or Arg8CG2 (right) following incubation with vehicle control, copper (100 μM, 48 h) or BCS (200 μM, 48 h). Relaxivity measurements were acquired at 37 °C in PBS (pH 7.4) at a proton Larmor frequency of 60 MHz. Error bars represent one standard deviation (n = 3) and statistical analysis were performed with a two-tailed Student’s t-test relative to the control. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01.

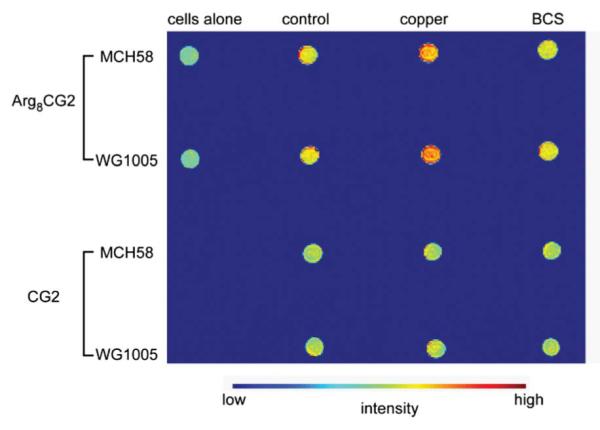

Finally, we collected phantom images of the two cell lines treated in the same manner as for the relaxivity studies (Fig. 6). Cells treated with CG2 or Arg8CG2 exhibit higher contrast than cells alone, with copper-treated cells displaying the highest signal. It is also possible to observe a difference in the contrast between the two cell lines for the copper- and Arg8CG2-treated samples. The phantom images also highlight the enhanced contrast of cells treated with Arg8CG2 compared to CG2-treated cells. These results indicate the potential of this probe for use in MRI studies in higher living model systems.

Fig. 6.

T1-weighted phantom images of MCH58 and WG1005 cells treated with CG2 or Arg8CG2 (500 μM, 1 h). Images were acquired at 25 °C at 1.5 T (~64 MHz proton Larmor frequency).

Conclusions

In summary, we have described the synthesis, relaxivity behavior and cellular characterization of Arg8CG2, a Cu+-responsive MRI contrast agent that exhibits improved cellular uptake. This work demonstrates the utility of the octaarginine group to promote cellular uptake and retention, and the great advantage that such behavior lends to in cellulo experiments. Using this new probe, we have been able to detect differences in copper accumulation between cells bearing a mutant copper transporter and wildtype cells. The clear differences in relaxivity between Atp7a mutant and wildtype cells as detected by Arg8CG2, and the resulting variation in contrast in phantom imaging experiments, points to the applicability of this probe for in vivo imaging in disease states. We have identified a number of animal models of copper mishandling diseases, to which we can apply Arg8CG2, including the toxic milk65 and Atp7b knockout mice,66 which are models for Wilson’s disease, and which exhibit markedly different copper distributions from wildtype mice.17,18 We are currently pursuing the use of Arg8CG2 in a variety of whole animal imaging studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the Packard Foundation, Amgen, Astra Zeneca, and Novartis, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIH GM 79465) for funding this work. C.J.C. is an Investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. E.J.N. was supported by a fellowship from the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851. E.L.Q. acknowledges a Branch Graduate Fellowship from UC Berkeley. We thank Ann Fischer and Michelle Richner (UCB Tissue Culture Facility) for expert technical assistance, Joern Larsen (Department of Earth Sciences, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory) for use of his ICP-MS instrument, and Suzanne Baker (Center for Functional Imaging, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory) for help collecting phantom MR images.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: Synthetic, spectroscopic, and cell assay protocols and data. See DOI: 10.1039/c2sc20273e

Notes and references

- 1.Que EL, Domaille DW, Chang CJ. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:1517–1549. doi: 10.1021/cr078203u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu J, Lu Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:9838–9839. doi: 10.1021/ja0717358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu J, Lu Y. Chem. Commun. 2007:4872–4874. doi: 10.1039/b712421j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wegner SV, Arslan H, Sunbul M, Yin J, He C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:2567–2569. doi: 10.1021/ja9097324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wegner SV, Sun F, Hernandez N, He C. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:2571–2573. doi: 10.1039/c0cc04292g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang L, McRae R, Henary MM, Patel R, Lai B, Vogt S, Fahrni CJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:11179–11184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406547102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller EW, Zeng L, Domaille DW, Chang CJ. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:824–827. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeng L, Miller EW, Pralle A, Isacoff EY, Chang CJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:10–11. doi: 10.1021/ja055064u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Domaille DW, Zeng L, Chang CJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:1194–1195. doi: 10.1021/ja907778b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taki M, Iyoshi S, Ojida A, Hamachi I, Yamamoto Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:5938–5939. doi: 10.1021/ja100714p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dodani SC, Domaille DW, Nam CI, Miller EW, Finney LA, Vogt S, Chang CJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:5980–5985. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009932108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dodani SC, Leary SC, Cobine PA, Winge DR, Chang CJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:8606–8616. doi: 10.1021/ja2004158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lim CS, Han JH, Kim CW, Kang MY, Kang DW, Cho BR. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:7146–7148. doi: 10.1039/c1cc11568e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chwiej J, Trace J. Elem. Med. Biol. 2010;24:78–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ide-Ektessabi A, Rabionet M. Anal. Sci. 2005;21:885–892. doi: 10.2116/analsci.21.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fodero-Tavoletti MT, Villemagne VL, Paterson BM, White AR, Li Q-X, Camakaris J, O’Keefe GJ, Cappai R, Barnham KJ, Donnelly PS. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2010;20:49–55. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peng F, Lutsenko S, Sun X, Muzik O. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2012;14:70–78. doi: 10.1007/s11307-011-0476-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirayama T, Van de Bittner GC, Gray L, Lutsenko S, Chang CJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:2228–2233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113729109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caravan P, Ellison JJ, McMurry TJ, Lauffer RB. Chem. Rev. 1999;99:2293–2352. doi: 10.1021/cr980440x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Werner EJ, Datta A, Jocher CJ, Raymond KN. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:8568–8580. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meade TJ, Taylor AK, Bull SR. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2003;13:597–602. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Que EL, Chang CJ. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010;39:51–60. doi: 10.1039/b914348n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aime S, Castelli D. Delli, Terreno E. Angew. Chem. 2002;114:4510–4512. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kálmán FK, Woods M, Caravan P, Jurek P, Spiller M, Tircsó G, Király R, Brücher E, Sherry AD. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:5260–5270. doi: 10.1021/ic0702926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang Y-T, Cheng C-M, Su Y-Z, Lee W-T, Hsu J-S, Liu G-C, Cheng T-L, Wang Y-M. Bioconjugate Chem. 2007;18:1716–1727. doi: 10.1021/bc070019s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chauvin T, Durand P, Bernier M, Meudal H, Doan B-T, Noury F, Badet B, Beloeil J-C, Tóth É. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:4370–4372. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Y, Sheth VR, Liu G, Pagel MD. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging. 2011;6:219–228. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Urbanczyk-Pearson LM, Meade TJ. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:341–350. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanaoka K, Kikuchi K, Urano Y, Nagano T. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2001;2:1840–1843. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee T, Zhang X.-a., Dhar S, Faas H, Lippard SJ, Jasanoff A. Chem. Biol. 2010;17:665–673. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lubag AJM, De Leon-Rodriguez LM, Burgess SC, Sherry AD. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:18400–18405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109649108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mishra A, Logothetis NK, Parker D. Chem.–Eur. J. 2011;17:1529–1537. doi: 10.1002/chem.201001548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kasala D, Lin T-S, Chen C-Y, Liu G-C, Kao C-L, Cheng T-L, Wang Y-M. Dalton Trans. 2011;40:5018–5025. doi: 10.1039/c1dt10033e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li W-S, Luo J, Chen Z-N. Dalton Trans. 2011;40:484–488. doi: 10.1039/c0dt01141j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patel D, Kell A, Simard B, Xiang B, Lin HY, Tian G. Biomaterials. 2011;32:1167–1176. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Que EL, Chang CJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:15942–15943. doi: 10.1021/ja065264l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Que EL, Gianolio E, Baker SL, Aime S, Chang CJ. Dalton Trans. 2010;39:469–476. doi: 10.1039/b916931h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Que EL, Gianolio E, Baker SL, Wong AP, Aime S, Chang CJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:8527–8536. doi: 10.1021/ja900884j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bonnet CS, Toth E. Future Med. Chem. 2010;2:367–384. doi: 10.4155/fmc.09.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang X.-a., Lovejoy KS, Jasanoff A, Lippard SJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:10780–10785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702393104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Allen MJ, MacRenaris KW, Venkatasubramanian PN, Meade TJ. Chem. Biol. 2004;11:301–307. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Terreno E, Crich SG, Belfiore S, Biancone L, Cabella C, Esposito G, Manazza AD, Aime S. Magn. Reson. Med. 2006;55:491–497. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hak S, Sanders HMHF, Agrawal P, Langereis S, Grüll H, Keizer HM, Arena F, Terreno E, Strijkers GJ, Nicolay K. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2009;72:397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2008.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kabalka GW, Davis MA, Moss TH, Buonocore E, Hubner K, Holmberg E, Maruyama K, Huang L. Magn. Reson. Med. 1991;19:406–415. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910190231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Allen MJ, Meade TJ. JBIC, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2003;8:746–750. doi: 10.1007/s00775-003-0475-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bhorade R, Weissleder R, Nakakoshi T, Moore A, Tung C-H. Bioconjugate Chem. 2000;11:301–305. doi: 10.1021/bc990168d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Curtet C, Maton F, Havet T. Invest. Radiol. 1998;33:752–761. doi: 10.1097/00004424-199810000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heckl S, Debus J, Jenne J, Pipkorn R, Waldeck W, Spring H, Rastert R, von der Lieth CW, Braun K. Cancer Res. 2002;62:7018–7024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wiener EC, Konda S, Shadron A, Brechbiel M, Gansow O. Invest. Radiol. 1997;32:748–754. doi: 10.1097/00004424-199712000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Casali C, Janier M, Canet E. Acad. Radiol. 1998;5:214–218. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(98)80109-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Endres PJ, Paunesku T, Vogt S, Meade TJ, Woloschak GE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:15760–15761. doi: 10.1021/ja0772389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Song Y, Xu X, MacRenaris KW, Zhang X-Q, Mirkin CA, Meade TJ. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48:9143–9147. doi: 10.1002/anie.200904666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Deshayes S, Morris MC, Divita G, Heitz F. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2005;62:1839–1849. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5109-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Matsui H, Tomizawa K, Lu YF, Matsushita M. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2003;4:151–157. doi: 10.2174/1389203033487270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rothbard JB, Jessop TC, Wender PA. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2005;57:495–504. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wender PA, Galliher WC, Goun EA, Jones LR, Pillow TH. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2007;60:452–472. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lewin M, Carlesso N, Tung CH, Tang XW, Cory D, Scadden DT, Weissleder R. Nat. Biotechnol. 2000;18:410–414. doi: 10.1038/74464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wunderbaldinger P, Josephson L, Weissleder R. Bioconjugate Chem. 2002;13:264–268. doi: 10.1021/bc015563u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhao M, Kircher MF, Josephson L, Weissleder R. Bioconjugate Chem. 2002;13:840–844. doi: 10.1021/bc0255236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.De Leon-Rodriguez LM, Kovacs Z, Esqueda-Oliva AC, Miranda-Olvera AD. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:6937–6940. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smith RM, Martell AE. Critical Stability Constants. Plenum Press; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jones SW, Christison R, Bundell K, Voyce CJ, Brockbank SMV, Newham P, Lindsay MA. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2005;145:1093–1102. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kaler SG. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2011;7:15–29. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bellingham SA, Lahiri DK, Maloney B, La Fontaine S, Multhaup G, Camakaris J. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:20378–20396. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400805200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Theophilos MB, Cox DW, Mercer JF. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1996;5:1619–1624. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.10.1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Huster D, Finegold MJ, Morgan CT, Burkhead JL, Nixon R, Vanderwerf SM, Gilliam CT, Lutsenko S. Am. J. Pathol. 2006;168:423–434. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.