Abstract

Because informed consent requires discussion of alternative treatments, proper consent for dialysis should incorporate discussion about other renal replacement options including kidney transplantation (KT). Accordingly, dialysis providers are required to indicate KT provision of information (KTPI) on CMS Form-2728; however, provider-reported KTPI does not necessarily imply adequate provision of information. Furthermore, the effect of KTPI on pursuit of KT remains unclear. We compared provider-reported KTPI (Form-2728) with patient-reported KTPI (in-person survey of whether a nephrologist or dialysis staff had discussed KT) in a prospective ancillary study of 388 hemodialysis initiates. KTPI was reported by both patient and provider for 56.2% of participants, by provider only for 27.8%, by patient only for 8.3%, and by neither for 7.7%. Among participants with provider-reported KTPI, older age was associated with lack of patient-reported KTPI. Linkage with the Scientific Registry for Transplant Recipients showed that 20.9% of participants were subsequently listed for KT. Patient-reported KTPI was independently associated with a 2.95-fold (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.54 to 5.66; P=0.001) higher likelihood of KT listing, whereas provider-reported KTPI was not associated with listing (hazard ratio, 1.18; 95% CI, 0.60 to 2.32; P=0.62). Our findings suggest that patient perception of KTPI is more important for KT listing than provider-reported KTPI. Patient-reported and provider-reported KTPI should be collected for quality assessment in dialysis centers because factors associated with discordance between these metrics might inform interventions to improve this process.

Keywords: transplantation, age disparities, CMS Form 2728, provision of information, listing

The informed consent process for any medical intervention requires a discussion of risks and benefits of the chosen treatment as well as alternative treatment options, their risks and benefits, and a rationale for selecting the chosen treatment.1,2 For patients with ESRD, the informed consent process for initiating hemodialysis should include a discussion of kidney transplantation (KT) as an alternative, regardless of patient age or appropriateness for this treatment option. If the patient is too old or is otherwise at high risk for transplantation, this should be explained to the patient during the informed consent discussion.3 This principle of informed consent is reflected in the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services requirement for providers to document on Form-2728 within 45 days of dialysis initiation either KT provision of information (KTPI) or a reason for not giving information.4 During the first 2 years in which KTPI questions were included, only approximately 70% of incident patients with ESRD were reported by their provider to be informed at the time of Form-2728 filing.5

Thus far, studies of KTPI have been limited to those of provider report5; however, even when KTPI is reported by the provider, whether adequate provision of information has been delivered to the patient and whether the patient perceives the information to have been delivered remain unknown. For example, in some clinical care and clinical research settings, providers have reported obtaining informed consent only for legal protection rather than patient understanding.6,7 Although studies of patient knowledge after provision of medical information have shown that patient characteristics, such as age, race, or education, might affect patient understanding,8 no studies have investigated patient perceptions of KTPI or factors associated with discordance between patient-reported and provider-reported KTPI.

The relationships between patient-reported KTPI, provider-reported KTPI, and steps in the process to KT access also remain unknown. Although various possible steps could be assessed, intermediate steps (e.g., referral and evaluation) require continued active participation from both the nephrologist and patient, and this continued engagement could be affected by KTPI as well. Because KT listing represents the final step in this process, it represents all steps of participation beginning with KTPI. Furthermore, because listing requires mandated reporting, whereas evaluation is not reliably captured, listing provides a more robust outcome. Given the potential for patient and provider discordance in KTPI, and the importance of patient knowledge in the shared decision-making process regarding KT, we explored the relationship between patient- and provider-reported KTPI. Furthermore, we explored patient characteristics associated with concordance or discordance. Finally, we estimated associations between KTPI and subsequent listing for KT.

Results

Study Population

Of 388 participants who had recently initiated hemodialysis, the average age was 56.3 years (SD 13.9), 27.3% were aged≥65 years, 45.4% were women, 67.5% were African American, 47.5% had seen a nephrologist for ≥12 months before dialysis initiation, and 20.9% were ultimately listed for KT. The median time on dialysis at enrollment was 2.1 months (interquartile range, 1.4–3.1) (Table 1). All participants were followed for the duration of the study, which had a median follow-up time of 2.2 years (interquartile range, 1.6–3.1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study population at dialysis initiation

| Participant Characteristic | Value (N=388) |

|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 56.3 (13.9) |

| Female sex | 45.4 |

| African American race | 67.5 |

| Marital status | |

| Married/cohabitating | 34.1 |

| Single | 25.5 |

| Separated/divorced | 26.6 |

| Widowed | 13.8 |

| Highest education level | |

| Grade school or less | 37.1 |

| High school | 20.5 |

| Postsecondary | 42.5 |

| Working | 16.0 |

| Current smoking | 20.9 |

| BMI | 28.3 (24.2, 34.1) |

| Number of comorbidities | 3 (2, 4) |

| Diabetes | 57.5 |

| Hypertension | 98.5 |

| Heart failure | 30.2 |

| Atherosclerotic disease | 23.2 |

| Cardiovascular disease, other | 22.9 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 19.9 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 7.2 |

| Asthma/COPD | 22.2 |

| HCV/HBV | 15.0 |

| Cancer history (prior 10–5 yr)a | 2.3 |

| Time on dialysis (mo) | 2.1 (1.4, 3.1) |

| Time between first seeing nephrologist and dialysis initiation (mo) | |

| 0 | 22.9 |

| <3 | 13.3 |

| 3 to <12 | 16.4 |

| ≥12 | 47.5 |

Data are presented as the percentage of the total study sample, mean (SD), or median (interquartile range). COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HCV, hepatitis C viral infection; HBV, hepatitis B viral infection.

Excluding those with a history within the prior 5 years and those with a history of only nonmelanoma skin cancer.

Provision of Information about KT

Providers reported KTPI in 84.0% of the participants, whereas only 64.4% of participants reported receiving it. KTPI was reported concordantly by both patient and provider in 56.2% of participants, concordantly by neither in 7.7%, discordantly by provider only in 27.8%, and discordantly by patient only in 8.3% (Table 2). The agreement between patient and provider was only slightly better than what would be expected by chance alone (63.9% observed agreement versus 59.8% expected agreement, κ=0.10).

Table 2.

Patient- and provider-reported provision of information about KT

| Patient-Reported KTPI | Provider-Reported KTPI | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| No | 30 | 108 | 138 |

| Yes | 32 | 218 | 250 |

| Total | 62 | 326 | 388 |

Provision of information about KT was reported by patient and provider in 56.2% of participants, provider only in 27.8%, patient only in 8.3%, and neither in 7.7%. The interrater agreement between patients and providers was only slightly better than what would be expected by chance alone (63.9% observed agreement versus 59.8% expected agreement; κ=0.10).

Patient-Provider Discordance in Provision of Information about KT

Older age was independently associated with discordant provider-only report of KTPI (i.e., for a given patient, the provider reported providing information but the patient reported no information was given). After adjusting for sex, race, education level, number of comorbidities, body mass index (BMI), current smoking, and seeing a nephrologist for ≥12 months before dialysis initiation, each 5-year increase in age through age 65 years was associated with 1.10-fold (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.00 to 1.21; P=0.05) greater likelihood and each 5-year increase in age beyond age 65 years was associated with an additional 1.23-fold greater likelihood (95% CI, 1.08 to 1.39; P=0.002) of provider-only report of KTPI. In other words, a person aged 75 years was 1.83-fold more likely to have provider-only reported KTPI compared with a person aged 55 years (i.e., 1.102×1.232). In the fully adjusted model, neither female sex (relative risk [RR], 1.17; 95% CI, 0.87 to 1.57; P=0.31) nor African-American race (RR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.59 to 1.09; P=0.20) was associated with provider-only discordance. Estimates were consistent in fully adjusted and parsimonious models (Table 3).

Table 3.

Associations between patient characteristics and patient-provider discordance in provision of information about KT

| Characteristic | Discordant Provider-Only Report of KTPI (n=326)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | Parsimoniousb | |

| Age (yr; per continuous per 5-yr increase); spline with knot at 65 | |||

| <65 | 1.10 (1.01 to 1.21) | 1.10 (1.00 to 1.21) | 1.12 (1.02 to 1.24) |

| ≥65 | 1.22 (1.08 to 1.38) | 1.23 (1.08 to 1.39) | 1.26 (1.11 to 1.44) |

| Female sex | 1.14 (0.84 to 1.56) | 1.17 (0.87 to 1.57) | |

| African American race | 0.71 (0.52 to 0.97) | 0.80 (0.59 to 1.09) | |

| Highest education level | |||

| Grade school or less | ref | ref | |

| High school | 0.54 (0.33 to 0.91) | 0.59 (0.36 to 0.98) | |

| Postsecondary | 0.78 (0.57 to 1.08) | 0.88 (0.64 to 1.21) | |

| Number of comorbidities | 1.09 (0.99 to 1.19) | 1.07 (0.97 to 1.17) | |

| BMI≥30 | 0.74 (0.53 to 1.03) | 0.91 (0.65 to 1.28) | |

| Current smoking | 1.49 (1.08 to 2.05) | 1.67 (1.18 to 2.36) | 1.66 (1.20 to 2.30) |

| Time between first seeing nephrologist and dialysis initiation (mo) | |||

| <12 | ref | ref | ref |

| ≥12 | 0.75 (0.54 to 1.03) | 0.65 (0.48 to 0.88) | 0.65 (0.48 to 0.88) |

Data are presented as the RR (95% CI). RRs and 95% CIs were modeled using modified Poisson regression. Age was modeled as a continuous variable using a linear spline term with a knot at age 65 years, and the risk was modeled per 5-year increase in age.

Limited to participants who had provider-reported KTPI (i.e., excluding participants with patient-only reported KTPI or neither patient- nor provider-reported KTPI).

Parsimonious model derived using Akaike information criteria from the adjusted model.

Provision of Information about KT and Listing

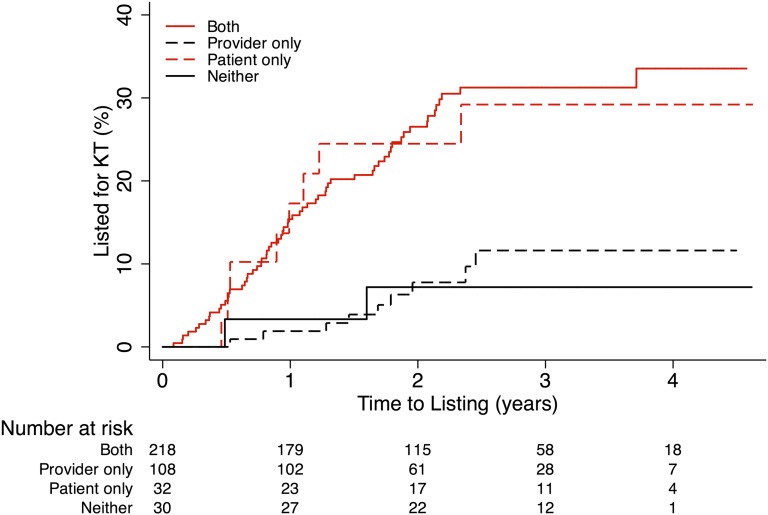

Of participants who were uninformed about KT according to both patient and provider, only 3.3% were listed for KT within 1 year of dialysis initiation. Likewise, of those who were informed according to the provider only, 1.9% were listed within 1 year of dialysis initiation. By contrast, of those receiving KTPI according to the patient only or according to both patient and provider, 17.3% and 15.4% were listed for KT within 1 year of dialysis initiation, respectively. With longer follow-up, this difference remained (Figure 1). For example, at 2 years, 7.2%, 7.8%, 24.5%, and 26.5% were listed among those with neither, provider-only KTPI, patient-only KTPI, and both patient and provider KTPI, respectively. Although two participants were marked as medically unfit by their provider, neither had patient- nor provider-reported KTPI, and neither was listed for KT.

Figure 1.

Listing for KT, by patient and provider report of provision of information. Estimated cumulative incidence of listing for KT by provider or patient report of provision of information. Curves are estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. The log-rank test for difference by provision of information and the log-rank test for trend across age groups are statistically significant (P<0.001). Entry (time zero) is the date of dialysis initiation. Participants are censored at time of listing for KT, death, or end of study.

Patient-reported KTPI was independently predictive of KT listing. Irrespective of provider-reported KTPI, and after adjusting for age, sex, race, number of comorbidities, BMI, smoking status, and time between first seeing a nephrologist and dialysis initiation, patient-reported KTPI was associated with 2.95-fold (95% CI, 1.54 to 5.66; P=0.001) higher likelihood of being listed for KT. By contrast, provider report was not associated with listing (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.18; 95% CI, 0.60 to 2.32; P=0.62), even in adjusted models that excluded patient-reported KTPI (aHR, 1.22; 95% CI, 0.62 to 2.40; P=0.56). Estimates were consistent in fully adjusted and parsimonious models (Table 4). In a sensitivity analysis in which the discordant patient-only group was excluded, inferences were consistent. Patient-reported KTPI was associated with 3.07-fold (95% CI, 1.51 to 6.25; P=0.002) higher likelihood of being listed for KT, whereas provider report was not associated with listing (aHR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.22 to 4.76; P=0.99). Similarly, in a sensitivity analysis in which those who participated in the survey before Form-2728 filing were excluded, patient-reported KTPI was associated with 3.25-fold (95% CI, 1.64 to 6.43; P=0.001) higher likelihood of being listed for KT, whereas provider report was not associated with listing (aHR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.57 to 2.22; P=0.73). Finally, although rates of death were nondifferential across the groups being compared, we performed a sensitivity analysis using death as a competing risk and found no change in inference; patient-reported KTPI was associated with 3.08-fold (95% CI, 1.66 to 5.69; P<0.001) higher likelihood of being listed for KT, whereas provider report was not associated with listing (aHR, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.61 to 2.35; P=0.53).

Table 4.

Associations between provision of information about KT and listing for transplantation

| Association | Listing among Participants Informed According to the Provider | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Parsimoniousb | |

| Provider-reported KTPI | 1.37 (0.70 to 2.65) | 1.18 (0.60 to 2.32) | |

| Patient-reported KTPI | 3.94 (2.08 to 7.43) | 2.95 (1.54 to 5.66) | 3.02 (1.57 to 5.78) |

Data are presented as the HR (95% CI). HRs were estimated using Cox proportional hazards models.

Adjusted for age, sex, race, number of comorbidities, BMI, and current smoking.

Parsimonious model derived using Akaike information criteria from the adjusted model. Adjusted for age, race, BMI, and smoking status.

Discussion

In this multicenter prospective cohort study of 388 patients who had recently initiated hemodialysis, only two thirds of participants whose nephrologist reported providing KT information confirmed receiving this information. Furthermore, only patient-reported KTPI was independently predictive of subsequent listing: participants were 2.95-fold more likely to be listed for KT if the participant reported receiving KT information from a nephrologist or dialysis staff, but no association was seen with provider-reported KTPI.

With only 64.4% of participants indicating that a nephrologist or dialysis staff had discussed KT with them, our study is consistent with the many other studies suggesting that knowledge of RRTs among patients with ESRD remains suboptimal.9,10 Discordance in our study population ranged from 25% to 50% (depending mostly on patient age), which is consistent with poor recall of treatment details, risks, and benefits conveyed during the informed consent process among patients undergoing medical procedures11 as well as healthy controls in clinical trials.12 In addition, our finding that older adults (despite excluding those with dementia) were less likely to report receiving KTPI even when they were informed according to their provider is consistent with the documented age disparity in referral and access to KT.5,13–16 In other words, older age is consistently associated with lack of access in all steps in the process to KT from provision of information to transplantation. Finally, whereas other studies have shown that provider-reported KTPI is associated with listing,5 our study suggests a novel mechanism in which patient perception of KTPI is actually what drives the association between KTPI and listing.

The exact mechanism for patient-only discordance among 8.3% of participants remains unclear. Nevertheless, this discordance is likely the result of Form-2728 filing before survey administration for these participants. Whereas Form-2728 must be filed within 45 days of dialysis initiation, the survey was administered within 6 months of dialysis initiation; therefore, some participants may have had an opportunity to receive KTPI between Form-2728 filing and survey administration. In fact, all but one participant with patient-only reported KTPI had Form-2728 filed before survey administration, and none of these participants were indicated as medically unfit or unsuitable on Form-2728 as a reason for lack of KTPI. This temporal difference, however, does not explain the 27.8% of participants with discordant provider-only KTPI, because Form-2728 also was filed before survey administration for these participants. Among the 326 participants who were informed according to their provider, only 37.7%, 17.5%, and 11.7% of participants reported KTPI by both nephrologist and dialysis staff, nephrologist only, and dialysis staff only, respectively.

This study has several other limitations. First, patient-reported KTPI was only captured at study entry and provider-reported KTPI was only captured at Form-2728 filing. However, Form-2728 was filed before survey administration for 94% of participants, giving the providers maximum opportunity to provide information before the patient was asked about this provision. Second, we did not capture referral or evaluation for KT, two intermediate outcomes between KTPI and listing; as such, we cannot be certain if a patient was not listed because they were not referred, or if they were not listed because they failed evaluation. However, bias would be expected only if provider- and patient-reported KTPI differentially affected referral, evaluation, and, ultimately, listing, and this differential effect is unlikely. Third, information about the provider was not collected, so associations with provider characteristics could not be determined. Finally, African Americans were over-represented in our study population compared with those initiating dialysis in the United States (67.5% versus 28%17). However, this difference would only bias our inferences if race modified the relationship between age and KTPI or between KTPI and listing. Because no interactions with race were identified, we feel confident that the over-representation of African Americans was unlikely to have affected our inferences; in fact, this over-representation might actually be advantageous in terms of statistical power to have detected such interactions.

This study also has several strengths. The novel collection of both patient and provider report of KTPI for the same patient allowed ascertainment of discordance between these constructs, which to our knowledge has not been previously studied. In addition, linkage to the national registry of patients who are waitlisted for transplantation enabled us to validate these constructs (i.e., to determine correlation between patient and/or provider report of KTPI and a clinically relevant outcome). Furthermore, the high prevalence of African American participants enabled us to evaluate disparities by race. Finally, by using an incident sampling method, prevalence sampling bias was minimized.18 Thus, our inferences are more likely to be generalizable to the total population of patients with ESRD rather than to a select group of survivors.

In conclusion, discordance between patient and provider report of KTPI was high, and only patient report of KTPI was predictive of listing. Whether KTPI was documented when information was not actually provided, whether information was provided but patients did not recall receiving it, or whether providers and patients disagree on what constitutes adequate KTPI remains unknown. Regardless, because patient perception of KTPI appears to be most important for listing, patient report might be a valuable litmus test of the quality of a provider’s KTPI. Empowering all patients to make informed treatment choices through informed consent and shared decision-making processes is the standard of care.19 Thus, exploration of better ways of informing patients about KT, particularly older adults, is needed, especially as indications for transplantation expand20–22 and survival and quality of life improve after transplantation.23–27 Finally, interventions to improve information disclosure and patient-provider communication may be useful in discussion of transplantation with patients initiating hemodialysis, because these have shown benefit in patient comprehension of treatment options, risks, and benefits in other clinical settings.8

Concise Methods

Study Population

This was a prospective cohort study of 388 patients initiating hemodialysis within the prior 6 months at 26 for-profit outpatient dialysis centers in Baltimore and 6 surrounding counties in Maryland. Participants completed in-person staff-administered surveys between January 2009 and March 2012 (ancillary study to the Predictors in Arrhythmic Cardiovascular Events study [R01-DK072367]). The parent study was designed to study sudden unexpected cardiac death in an incident dialysis population with eligibility criteria including age≥18 years and English speaking and strict exclusion criteria including living in a hospice, nursing facility, or prison; having a pacemaker or automatic implantable cardioverter defibrillator; or having cancer other than nonmelanoma skin cancer within the prior year. The parent study visits included exposure to ionizing radiation so those who were pregnant or breastfeeding were also excluded. Those who were unable to complete consent or follow through on a study visit and those with a diagnosis of dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, or schizophrenia were also excluded, although participants with some mild cognitive deficits may have participated. Of eligible, screened potential participants for the parent study, 59% were enrolled. The ancillary study also excluded individuals who were HIV infected and those who had a diagnosis of cancer other than nonmelanoma skin cancer within the prior 5 years, because these are relative contraindications to transplantation, as well as individuals who were preemptively listed for KT (i.e., listed before initiation of dialysis), because they had already achieved the outcome of listing for transplantation. Participants who were missing Form-2728 were also excluded (n=4). All participants provided informed consent. The Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures.

Participant Characteristics

Demographics (age, sex, race, education, employment, household size, and income), alcohol use, and time between first seeing a nephrologist and dialysis initiation were obtained through participant self-report. Current smoking was assessed using by self-reported data augmented with data from Form-2728. BMI was calculated from self-reported height and weight. The number of comorbidities was assessed using self-reported medical history and augmented with data from Form-2728. Comorbidities included hypertension, diabetes, heart failure, atherosclerotic disease, cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hepatitis C or hepatitis B infections, and history of cancer excluding nonmelanoma skin cancers 5 to 10 years before study entry. Time on dialysis was obtained from Form-2728.

Provision of Information about KT

KTPI was assessed in two ways: provider-reported KTPI and patient-reported KTPI. Specifically, copies of Form-2728 were obtained from participants’ medical records to determine whether the provider reported informing patients. Participants were asked two dichotomous (yes/no) questions as to whether a nephrologist or dialysis staff had discussed KT with them; participant report of discussion with a nephrologist only, dialysis staff only, or both was considered as patient-reported KTPI.

Patient-Provider Discordance in Provision of Information about KT

The relationship between patient and provider report of KTPI was assessed, and a κ statistic was calculated. Univariate and multivariable linear models using modified Poisson regression28,29 were used to estimate the RRs of discordant provider-only KTPI and were limited to only participants who were informed according to Form-2728. Two models were fit to ensure that inferences were not sensitive to covariate selection: one based on statistical significance or a priori biologic rationale and one empirically reflecting optimal parsimony by minimizing the Akaike information criterion. The best functional form of age was determined empirically to be continuous with a linear spline at age 65 years for univariate and multivariable models of the RR of provider-only KTPI.

Listing for KT

This study used data from the Scientific Registry for Transplantation (SRTR). The SRTR data system includes data on all donors, waitlisted candidates, and transplant recipients in the United States, submitted by members of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. The US Department of Health and Human Services Health Resources and Services Administration provides oversight to the activities of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and SRTR contractors. Study participant data were linked to SRTR data for KT listing date. No participants received a living donor KT before listing. The associations between KTPI and subsequent listing for KT were estimated using Cox models. Proportional hazards assumptions were assessed by visual inspection of complimentary log-log plots. Participants entered the study at date of dialysis initiation and were censored at listing date, date of death, or last available SRTR date for listing (June 30, 2013). Two models were fit to ensure that inferences were not sensitive to covariate selection: one based on statistical significance or a priori biologic rationale and one empirically reflecting optimal parsimony by minimizing the Akaike information criterion.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were performed using STATA 12.1/SE software (College Station, TX).

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the study participants and the staff at the participating dialysis clinics.

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01-AG042504 and R21-AG034523 to D.L.S., R01-DK072367 to R.S.P., and K01-AG043501 to M.M.-D.), the National Institute on Aging (T32-AG000247 to M.L.S.), and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (F32-DK093218 to B.O.). M.M.-D. is also supported by the American Society of Nephrology Carl W. Gottschalk Research Award as well as a grant from the Johns Hopkins Pepper Center (2P30-AG021334-11).

The data reported here have been supplied by the Minneapolis Medical Research Foundation as the contractor for the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR). The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and in no way should be seen as an official policy of or interpretation by the SRTR or the US government.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

See related editorial, “Asking Dialysis Patients About What They Were Told: A New Strategy for Improving Access to Kidney Transplantation?,” on pages 2683–2685.

References

- 1.Appelbaum P, Lidz C, Miesel A: Informed Consent: Legal Theory and Practice, New York, Oxford University Press, 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Health : Reference Guide to Consent for Examination or Treatment, London, Department of Health, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wachterman MW, Marcantonio ER, Davis RB, Cohen RA, Waikar SS, Phillips RS, McCarthy EP: Relationship between the prognostic expectations of seriously ill patients undergoing hemodialysis and their nephrologists. JAMA Intern Med 173: 1206–1214, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: Form CMS: 2728; ESRD Medical Evidence Report Medicare Entitlement and/or Patient Registration. OMB #0938-0046 January 27, 2012; Available from: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/CMS-Forms/CMS-Forms/Downloads/CMS2728.pdf. Accessed May 3, 2014

- 5.Kucirka LM, Grams ME, Balhara KS, Jaar BG, Segev DL: Disparities in provision of transplant information affect access to kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant 12: 351–357, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jefford M, Moore R: Improvement of informed consent and the quality of consent documents. Lancet Oncol 9: 485–493, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cahana A, Hurst SA: Voluntary informed consent in research and clinical care: An update. Pain Pract 8: 446–451, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Werner A, Holderried F, Schäffeler N, Weyrich P, Riessen R, Zipfel S, Celebi N: Communication training for advanced medical students improves information recall of medical laypersons in simulated informed consent talks—a randomized controlled trial. BMC Med Educ 13: 15, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finkelstein FO, Story K, Firanek C, Barre P, Takano T, Soroka S, Mujais S, Rodd K, Mendelssohn D: Perceived knowledge among patients cared for by nephrologists about chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease therapies. Kidney Int 74: 1178–1184, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright JA, Wallston KA, Elasy TA, Ikizler TA, Cavanaugh KL: Development and results of a kidney disease knowledge survey given to patients with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 57: 387–395, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lavelle-Jones C, Byrne DJ, Rice P, Cuschieri A: Factors affecting quality of informed consent. BMJ 306: 885–890, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fortun P, West J, Chalkley L, Shonde A, Hawkey C: Recall of informed consent information by healthy volunteers in clinical trials. QJM 101: 625–629, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Segev DL, Kucirka LM, Oberai PC, Parekh RS, Boulware LE, Powe NR, Montgomery RA: Age and comorbidities are effect modifiers of gender disparities in renal transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 621–628, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vamos EP, Novak M, Mucsi I: Non-medical factors influencing access to renal transplantation. Int Urol Nephrol 41: 607–616, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grams ME, Kucirka LM, Hanrahan CF, Montgomery RA, Massie AB, Segev DL: Candidacy for kidney transplantation of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 60: 1–7, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kucirka LM, Grams ME, Lessler J, Hall EC, James N, Massie AB, Montgomery RA, Segev DL: Association of race and age with survival among patients undergoing dialysis. JAMA 306: 620–626, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Renal Data System : USRDS 2009 Annual Data Reports: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan KC, Wang MC: Estimating incident population distribution from prevalent data. Biometrics 68: 521–531, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farrell EH, Whistance RN, Phillips K, Morgan B, Savage K, Lewis V, Kelly M, Blazeby JM, Kinnersley P, Edwards A: Systematic review and meta-analysis of audio-visual information aids for informed consent for invasive healthcare procedures in clinical practice. Patient Educ Couns 94: 20–32, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heldal K, Hartmann A, Grootendorst DC, de Jager DJ, Leivestad T, Foss A, Midtvedt K: Benefit of kidney transplantation beyond 70 years of age. Nephrol Dial Transplant 25: 1680–1687, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang E, Segev DL, Rabb H: Kidney transplantation in the elderly. Semin Nephrol 29: 621–635, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jassal SV, Krahn MD, Naglie G, Zaltzman JS, Roscoe JM, Cole EH, Redelmeier DA: Kidney transplantation in the elderly: A decision analysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 187–196, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chuang FP, Novick AC, Sun GH, Kleeman M, Flechner S, Krishnamurthi V, Modlin C, Shoskes D, Goldfarb DA: Graft outcomes of living donor renal transplantations in elderly recipients. Transplant Proc 40: 2299–2302, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gill JS, Schaeffner E, Chadban S, Dong J, Rose C, Johnston O, Gill J: Quantification of the early risk of death in elderly kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 13: 427–432, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rao PS, Merion RM, Ashby VB, Port FK, Wolfe RA, Kayler LK: Renal transplantation in elderly patients older than 70 years of age: Results from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients. Transplantation 83: 1069–1074, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, Ojo AO, Ettenger RE, Agodoa LY, Held PJ, Port FK: Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med 341: 1725–1730, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neipp M, Karavul B, Jackobs S, Meyer zu Vilsendorf A, Richter N, Becker T, Schwarz A, Klempnauer J: Quality of life in adult transplant recipients more than 15 years after kidney transplantation. Transplantation 81: 1640–1644, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Behrens T, Taeger D, Wellmann J, Keil U: Different methods to calculate effect estimates in cross-sectional studies. A comparison between prevalence odds ratio and prevalence ratio. Methods Inf Med 43: 505–509, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E: Easy SAS calculations for risk or prevalence ratios and differences. Am J Epidemiol 162: 199–200, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]