Abstract

Much effort has been made to stratify multiple myeloma patients for targeted therapy. However, responses have been varied and improved patient stratifications are needed. Forty-five diagnostic samples from multiple myeloma patients (median age 65 years) were stratified cytogenetically as 15 having non-hyperdiploidy, 20 having hyperdiploidy and 10 having a normal karyotype. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) assays with FGFR3/IGH, CCND1/IGH, IGH/MAF, RB1 and TP53 probes on bone marrow samples showed that IGH rearrangements were the most common abnormality in the non-hyperdiploid group but these were also found among hyperdiploid patients and patients with normal cytogenetics. Of these, FGFR3/IGH rearrangements were most frequent. Deletion of RB1/monosomy 13 was the most common genetic abnormality across the three groups and was significantly higher among non-hyperdiploid compared to hyperdiploid patients. On the other hand, the study recorded a low incidence of TP53 deletion/monosomy 17. The FGFR3/IGH fusion was frequently seen with RB1 deletion/monosomy 13. FISH with 1p36/1q21 and 6q21/15q22 probes showed that amplification of 15q22 was seen in all of the hyperdiploid patients while amplification of 1q21, Amp(1q21), characterized non-hyperdiploid patients. In contrast, deletions of 1p36 and 6q21 were very rare events. Amp(1q21), FGFR3/IGH fusion, RB1 deletion/monosomy 13, and even TP53 deletion/monosomy 17 were seen in some hyperdiploid patients, suggesting that they have a less than favorable prognosis and require closer monitoring.

Keywords: Amp(1q21), FISH panel, Hyperdiploidy, Non-hyperdiploidy

Introduction

The genetic characteristics of multiple myeloma (MM) have been widely studied because of the prognostication they confer to patients in response to therapy. Therefore, concerted efforts are made to characterize the MM cytogenetic subtypes so as to allow more accurate risk stratification of patients and to inform treatment decisions. This heterogeneous disease has been broadly categorized into two distinct cytogenetic groups according to risk stratification; non-hyperdiploid and hyperdiploid [1–5]. The former is putatively linked to a poorer overall survival while the latter group responds better to treatment. However, attempts to obtain a higher detection rate of chromosomal abnormality have been hampered by the indolent nature of plasma cells in culture with the resultant low pick up rate of only about 30–45 % in most cases by cytogenetic investigations [6]. To circumvent the limitations of karyotyping which are dependent on the availability of metaphases from actively dividing plasma cells, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) assays have been employed as adjunct tests. The utilization of FISH has enabled the detection rate of chromosomal abnormalities to rise over 80 % [7, 8], thereby providing more patients with a firm prognostication. FISH has also enabled the detection of chromosomally cryptic rearrangements which are important poor prognostic markers such as the FGFR3/IGH and IGH/MAF fusions. These translocations have been shown to be much more common among the non-hyperdiploid group compared to the hyperdiploid group. More recently, amplification of 1q21, Amp(1q21), is also thought to be associated with a poor prognosis [9, 10], as well as deletion of chromosome 1p and 6q regions [11, 12], while gains of chromosome 15 is common in hyperdiploid MM [13].

This study undertook to examine the incidences of Amp(1q21), deletion 1p and deletion 6q in MM patients using FISH probes to determine whether patients with a hyperdiploid karyotype might still harbor these abnormalities and therefore have a less than favorable outcome. The study also sought to determine the characteristic recurring rearrangements in normal diploid, non-hyperdiploid and hyperdiploid patients using the multiple myeloma FISH panel.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Sample Collection

This retrospective study included a limited series of 45 consecutive bone marrows that have been morphologically confirmed as MM, comprising 19 males and 26 females, between the ages of 46–84 years (median 65 years). They were referred for diagnostic cytogenetic analysis at the Singapore General Hospital’s Cytogenetics Laboratory between January 2007 and November 2010. Bone marrow samples were routinely aspirated for smears, flow cytometry and for cytogenetic studies.

The hospital’s Ethics Committee had approved all bone marrow aspirates and subsequent testing pertaining to this work and therefore the work has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. All persons have given their informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study.

Cytogenetic Analysis

The bone marrow specimens were each established as a 10 ml 24 h unstimulated culture and a 10 ml 72 h culture with IL6 (Roche Diagnostics Corp., IN, USA). The patients were stratified into a normal diploid karyotype group (N), a hyperdiploid group (H) if they had between 48 and 74 chromosomes and were associated with the usual trisomies especially 5, 9, 11, 15, and 21, and a non-hyperdiploid group (NH) if they had hypodiploidy, pseudodiploidy, or near tetraploidy [14].

Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization

A FISH panel comprising FGFR3/IGH, CCND1/IGH, IGH/MAF, RB1 and TP53 probes (Abbott Molecular, IL, USA) was performed on all samples. A hyperdiploidy FISH panel was also available on request, comprising probes for the centromeres of chromosomes 9, 11 and 15 (Abbott). FISH with probes using the 1q21/1p36, and 6q21/15q22 probe set (Poseidon, KREATECH Biotechnology B.V., Amsterdam, The Netherlands) was also performed on the archival bone marrow cell pellets.

All FISH assays were carried out in accordance to the manufacturers’ specifications. Briefly, cell pellets were obtained after bone marrow harvest for slide-making. A circle with a 12 mm diameter was etched on the underside of the slide and a drop of cell suspension was placed over it and allowed to dry. The slide was appropriately labeled with the patient’s particulars and FISH probes to be used. No prior plasma cell enrichment technique or cytoplasmic immunoglobulin-FISH (cIg-FISH) labeling was performed but each slide was carefully screened for abnormalities during scoring.

Two hundred nuclei were enumerated for each FISH probe with the FISH Panel while 100 cells each were scored with the 1q21/1p36, and 6q21/15q22 probe set. Enumeration was performed by two scorers. Cut-off values were established by the laboratory previously during validation studies.

Statistics

χ2 and Fisher’s exact tests were used where appropriate. A p value of <0.05 was deemed significant. Overall survival (OS) is defined as the percentage of patients who are still alive at last follow up, after they were diagnosed with cancer. Progression free survival (PFS) is defined as the length of time after start of treatment with no progression of disease.

Results

Cytogenetic analysis determined the patients as 15 belonging to the NH group, 20 to the H group and 10 to the N group. Table 1 shows the number of abnormalities detected by the MM FISH panel and the 1q21/1p36, and 6q21/15q22 probe sets associated with each group.

Table 1.

Abnormal FISH results in the NH, H and N groups(N = 45)

| Genetic abnormality | NH (N = 15) | H (N = 20) | N (N = 10) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FGFR3/IGH fusion | 10 (66.7 %)a | 3 (15.0 %)a | 5 (50.0 %) | 18] | 23 |

| CCND1/IGH fusion | 3 (20.0 %) | 0 | 0 | 3 | |

| IGH/MAF fusion | 2 (13.3 %) | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| DelRB1/monosomy 13 | 12 (80 %)b | 6 (30.0 %)b | 6 (60.0 %) | 24 | |

| DelTP53/monosomy 17 | 4 (26.7 %) | 1 (5.0 %) | 1 (10 %) | 6 | |

| Del1p36 | 1 (6.7 %) | 1 (5.0 %) | 0 | 2 | |

| Amp(1q21) | 10 (66.7 %)c | 7 (36.8 %)c | 3 (30.0 %) | 20 | |

| Del(6q21) | 1 (6.7 %) | 1 (5.0 %) | 0 | 2 | |

| Amp(15q22) | 5 (33.3 %)d | 20 (100 %)d/e | 2 (20.0 %)e | 27 |

FISH abnormalities were not mutually exclusive

DelRB1 deletion of RB1, DelTP53 deletion of TP53

a–e, χ 2 test or Fisher’s exact test, significant, p < 0.05 (data with significant differences shown only)

There were 23 IGH rearrangements seen altogether. IGH rearrangements were more commonly associated with the NH and N groups which accounted for 66.7 % and 50.0 % of the cases, respectively, as opposed to the H group (15 %). Among these, the FGFR3/IGH rearrangement was the most frequent IGH aberration. There were just 3 cases of CCND1/IGH and 2 cases of IGH/MAF which were found only in the NH group. Deletion of RB1/monosomy 13 (DelRB1/monosomy 13) was the single most common abnormality ascertained by the FISH panel and common to all groups but was significantly higher in the NH group (NH vs. H, p < 0.05). There was a very low incidence of DelTP53/monosomy and there were no significant differences across all three groups.

There were 17 1p36/1q21 and 6q21/15q22 abnormalities in the NH group, 29 abnormalities in the H group, and just 5 abnormalities in the N group. Amp(1q21) and Amp(15q22) were the predominant abnormalities. Amp(1q21) was significantly more frequent in the NH group (66.7 %) than in the H group (36.8 %). In contrast, Amp(15q22) characterized the H group (100 %) compared to the NH (33.3 %) and N (20 %) groups. Deletions of 1p36 and 6q21 were rare events. There were just 2 cases of Del(1p36) with 1 case each in the NH and H groups, as well as 1 case each of Del(6q21) in the NH and H groups.

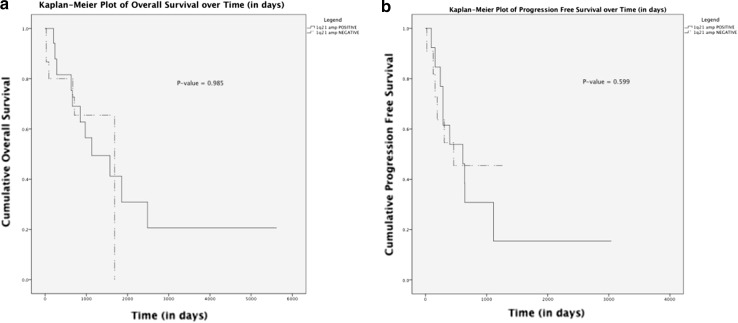

In determining the overall survival (OS), 34 patients were included in the final analysis. Seventeen patients were documented as deceased. Eleven out of 18 patients (61 %) were Amp(1q21) positive and 6/16 patients (37.5 %) were Amp(1q21) negative. Although more patients seemed to die in the Amp(1q21) positive group, the median overall survival for both the groups was similar, 958 days in the Amp(1q21) positive group and 973 days in the Amp(1q21) negative group p > 0.05).

Twenty-five patients were included in the calculation of progression free survival (PFS), depending on whether they achieved a best response via treatment. The median PFS was 460 days. Overall, 16 patients relapsed from best response (64 %). Ten out of 14 patients (71.4 %) who were Amp(1q21) positive and 6 out of 11 (54 %) who were Amp(1q21) negative relapsed from best response. It appeared that more patients from the Amp(1q21) positive group were relapsing from best response.

Out of the 45 patients, 24 (53.3 %) had DelRB1/monosomy 13. The FGFR3/IGH fusion was highly associated with DelRB1/monosomy 13 (62.5 %). In contrast, DelTP53/monosomy 17 appeared to be independent of DelRB1/monosomy 13, co-occurring in only 20.8 %. There were too few cases of CCND1/IGH and IGH/MAF fusions for a statistical analysis (Table 2).

Table 2.

DelRB1/monosomy 13 association with FGFR3/IGH and DelTP53/monosomy 17 abnormalities (abn.)

| Genetic abnormality | DelRB1/monosomy 13 positive | DelRB1/monosomy 13 negative | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. abn. | Total | % | No. abn. | Total | % | p | |

| FGFR3/IGH | 15 | 24 | 62.5 | 3 | 21 | 14.3 | 0.001 |

| DelTP53/monosomy 17 | 5 | 24 | 20.8 | 2 | 21 | 9.5 | >0.05 |

There were 19 (42.2 %) patients with Amp(1q21) out of the 45 patients (Table 3). Amp(1q21) was positively correlated with both FGFR3/IGH fusion (57.9 %) and DelRB1/monosomy 13 (73.7 %). However, Amp(1q21) was not significantly associated with DelTP53/monosomy 17 (26.3 %).

Table 3.

Amp(1q21) associations with other abnormalities (abn.)

| Genetic abnormality | Amp(1q21) positive patients | Amp(1q21) negative patients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. abn. | Total | % | No. abn. | Total | % | p | |

| FGFR3/IGH | 11 | 19 | 57.9 | 7 | 26 | 26.9 | 0.037 |

| DelRB1/monosomy 13 | 14 | 19 | 73.7 | 10 | 26 | 38.5 | 0.020 |

| DelTP53/monosomy 17 | 5 | 19 | 26.3 | 2 | 26 | 7.7 | >0.05 |

Discussion

Multiple myeloma is actually a heterogeneous group of diseases with different cytogenetic abnormalities conveniently consolidated under one main disease type. Much effort has therefore been made to further delineate MM patients according to their response to treatment, in particular the grouping of patients into the poor prognostic NH group and the better prognostic H group [15, 16] and the ISS staging based on serum β2M levels [17]. Furthermore, specific chromosomal abnormalities have been determined to portend an unfavorable prognosis. IGH fusions with FGFR3 and MAF, deletion of TP53 by FISH, and deletion 13q14 by cytogenetics are all associated with a poor outcome. The stratification of patients into the two groups has resulted in better identification of patients for aggressive treatment. Despite this, responses have been varied [18–20]. Most recently, the International Myeloma Workshop issued a consensus recommendation for high risk stratification of newly diagnosed multiple myeloma to include the above and added that patients in good-risk who show these abnormalities at relapse are considered having a high risk [21].

The results from this current study are in agreement with the current literature that IGH translocations occur much more frequently in the NH group, accounting for 65.2 % of IGH translocations with FGFR3 as the predominant partner (Table 1). This rearrangement was also seen in the H group but the incidence was significantly lower, in keeping with the poor prognostication of the NH group. In contrast, CCND1/IGH and IGH/MAF rearrangements were far fewer and only present in the NH group. The picture is less clear with the N group owing to the limited sample size of just 10 patients. By extrapolation, the incidence of FGFR3/IGH fusions is also quite significant in this normal cytogenetics group which may simply reflect a failure to detect the abnormal clone.

The most common genetic lesion was DelRB1/monosomy 13 in all three groups. This is in concordance with previous publications [16, 20, 23]. The finding is consistent with reports that alterations of RB1 are early events in multiple myeloma.

Among all prognostic markers, DelTP53/monosomy 17 is considered the worst prognosis and a late event in the evolution of MM [23]. Although this abnormality was present in all three groups, it appeared at very low frequencies. The observation of low frequencies was expected because these were all patients referred at diagnosis.

The FGFR3/IGH fusion is reportedly closely associated with DelRB1/monosomy 13 [23, 24]. In this study, FGFR3/IGH and DelRB1/monosomy 13 were also shown to be highly correlated (Table 2). This lends further support that DelRB1/monosomy 13 is a purported early event in the evolution of MM prior to divergence into the NH and H groups [25, 26]. On the other hand, TP53 abnormalities were not associated with DelRB1/monosomy 13. The finding is consistent with the current knowledge that TP53 abnormalities are late events.

More recently, deletions of 1p and amplifications of 1q were found to feature strongly in patients with MM and are believed to portend a poor outcome [4, 9, 25–28]. Amp(1q21) was a common abnormality (66.7 %) in the NH group but it was also present in 36.8 % of H patients, and in 30 % of N patients. Cremer et al. (2005) [23] reported that these patients tended to have significantly higher β2-microglobulin values and suggested that Amp(1q21) is an early event that can lead to either non-hyperdiploidy or hyperdiploidy. Our data was too small to stratify between these prognostic groups in determining the OS and PFS so the Kaplan–Meier curves generated were based on all patients with and without Amp(1q21) (Fig. 1a, b). Although the numbers are limited, it appears that the Amp(1q21) positive group showed reduced overall survival and progression free survival with more patients relapsing from partial response or better. Our data is line with published data [20, 29]. The OS and PFS data suggest that H patients who have Amp(1q21) may have a less favorable prognosis. Indeed, as shown earlier, some of these patients also had DelTP53/monosomy 17. Del(1p36) and Del(6q21) were much rarer events in this study. The low incidences suggest that these probes may be of limited clinical utility. It should be noted that the minimum commonly deleted region in the p-arm of chromosome 1 was determined to be between 1p12 and 1p21.1 [30]. In a study of 203 patients, Chang et al. (2007) [12] reported that 1p21 deletions are closely associated with 1q21 gains and are an independent adverse prognostic factor in terms of progression-free survival and shorter overall survival. Our use of the commercial 1p36 probe (KREATECH) outside the 1p12–1p21.1 region could have led to the erroneous low numbers of 1p deletions and precluded any correlative investigation.

Fig. 1.

a, b. Overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) curves of patients with and without Amp(1q21) abnormality

As expected, the H group had far more frequent gains of 15q22 with all cases showing this abnormality, compared to 33.3 % in the NH group and 20 % in the N group. This correlated well with the cytogenetic findings of gains of an entire or partial chromosome 15 which were apparent in 14 out of the 20 hyperdiploid cases [14]. This underscores the importance of including the chromosome 15 enumeration probe for interphase FISH assay for hyperdiploid cases, in addition to probes for chromosomes 9 and 11 which are also commonly seen in this group of patients.

A close association reportedly exists between Amp(1q21) and translocations involving IGH, such as FGFR3/IGH, as well as del(13q14) [9, 12, 31]. The current study found that Amp(1q21) was significantly associated with FGFR3 and DelRB1/monosomy 13 but not with DelTP53/monosomy 17 (Table 3). This might reflect the aggressive tumorigenesis in the NH group in particular, both abnormalities being independent prognosticators of poor outcome. Chen et al. (2007) found that while Amp(1q21) was significantly associated with del(13q14) there was no association with t(4;14) [32]. This disparity might be due to their erroneous selection of the CEP1 probe for 1q amplifications. Such a discrepancy highlights the importance of probe choice in routine diagnostic assays as was the case with our use of the commercial 1p36 probe instead of 1p21. The close correlation between Amp(1q21) with DelRB1/monosomy 13 again lends support that Amp(1q21) is an early event in the evolution of MM.

In the current study, no plasma cell enrichment procedure or cIg-staining was performed with the FISH assay. Despite this, the detection rate of genetic abnormalities such as DelRB1/monosomy 13 obtained by our protocol are similar to some plasma cell enrichment studies which reported incidences of just over 40 % [20, 29]. During FISH enumeration, cells were scored based on certain established in-house laboratory criteria such as the presence of enlarged cytoplasm and large cell morphology. These cells most often harbor genetic changes and are invariably plasma cells. Therefore, we felt that no plasma cell enrichment or cIg-FISH techniques were necessary in this study.

Conclusion

In this study, Amp(1q21) was observed even among hyperdiploid patients. Some of these patients were also found to be FGFR3/IGH positive and who may in rarer instances also harbor a deleted TP53 gene/monosomy 17. Such abnormalities would almost certainly confer a less favorable prognosis, as evidenced by more of such patients relapsing. The study recommends that these patients be monitored more closely. The current study is admittedly limited in terms of the number of patients recruited because multiple myeloma is a rare hematological disease, particularly so in Singapore. Moreover, we have not done any clinical correlation beyond survival as the prognostic staging data has not been included in the study. More patients will need to be assessed to support the findings of this study with regard to the cytogenetic profiling of our population.

Acknowledgments

This study was partly supported by the SingHealth Research Fund SHF/FG426P/2009.

References

- 1.Smadja NV, Bastard C, Brigaudeau C, et al. Hypodiploidy is a major prognostic factor in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2001;98:2229–2238. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.7.2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smadja NV, Leroux D, Soulier J, et al. Further cytogenetic characterization of multiple myeloma confirms that 14q32 translocations are very rare event in hyperdiploid cases. Genes Chromosom Cancer. 2003;38:234–239. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pratt G. Molecular aspects of multiple myeloma. J Clin Mol Pathol. 2002;55:273–283. doi: 10.1136/mp.55.5.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Debes-Marun CS, Dewald GW, Bryant S, et al. Chromosome abnormalities clustering and implications for pathogenesis and prognosis in myeloma. Leukemia. 2003;17:427–436. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaughnessy J, Jacobson J, Sawyer J, et al. Continuous absence of metaphase defined cytogenetic abnormalities especially of chromosome 13 and hypodiploidy assures long term survival in multiple myeloma treated with total therapy I: interpretation in the context of global gene expression. Blood. 2003;101:3849–3856. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rajkumar SV, Fonseca R, Dewald GW, et al. Cytogenetic ab-normalities correlate with the plasma cell labeling index and extent of bone marrow involvement in myeloma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1999;113:73–77. doi: 10.1016/S0165-4608(99)00009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drach J, Schuster J, Nowotny H, et al. Multiple myeloma: high incidence of chromosomal aneuploidy as detected by interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization. Cancer Res. 1995;55:3854–3859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flactif M, Zandecki M, Lai JL, et al. Interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) as a powerful tool for the detection of aneuploidy in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 1995;9:2109–2114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fonseca R, Van Wier SA, Chng WJ, et al. Prognostic value of chromosome 1q21 gain by fluorescent in situ hybridization and increase CKS1B expression in myeloma. Leukemia. 2006;20:2034–2040. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanamura I, Stewart JP, Huang Y, et al. Frequent gain of chromosome band 1q21 in plasma cell dyscrasias detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization: incidence increases from MGUS to relapsed myeloma and is related to prognosis and disease progression following tandem stem-cell transplantation. Blood. 2006;108:1724–1732. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-009910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nimura T, Miura I, Kobayashi Y, et al. Cytogenetic study of 48 patients with multiple myeloma and related disorders. J Clin Exp Hematopathol. 2003;43:53–60. doi: 10.3960/jslrt.43.53. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang H, Qi C, Xu W, et al. 1p21 deletion is a novel poor prognostic factor in multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2007;139:51–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Avet-Loiseau H, Li C, Magrangeas F, et al. Prognostic significance of copy-number alterations in multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4585–4590. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.6136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim AST, Lim TH, See KHS, et al. Cytogenetic and molecular aberrations of multiple myeloma patients: a single center study in Singapore. Chin Med J. 2013;126:1872–1877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fonseca R, Blood E, Rue M, et al. Clinical and biologic implications of recurrent genomic aberrations in myeloma. Blood. 2003;101:4569–4575. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan D, Teoh G, Lau LC, et al. An abnormal non-hyperdiploid karyotype is a significant adverse prognostic factor for multiple myeloma in the Bortezomib era. Am J Hematol. 2010;85:752–756. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greipp PR, San Miguel J, Durie BG, et al. International staging system for multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3412–3420. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barlogie B, Shaughnessy J, Tricot G, et al. Treatment of multiple myeloma. Blood. 2004;103:20–32. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang H, Qi X, Jiang A, et al. 1p21 deletions are strongly associated with 1q21 gains and are an independent adverse prognostic factor for the outcome of high-dose chemotherapy in patients with multiple myeloma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45:117–121. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Avet-Loiseau H, Facon T, Grosbois B, et al. Oncogenesis of multiple myeloma: 14q32 and 13q chromosomal abnormalities are not randomly distributed, but correlate with natural history, immunological features, and clinical presentation. Blood. 2002;99:2185–2191. doi: 10.1182/blood.V99.6.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Munshi NC, Andersen KC, Bergsagel PL, et al. Consensus recommendations for risk stratification in multiple myeloma: report on the International Myeloma Workshop Consensus Panel 2. Blood. 2011;117:4696–4700. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-300970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liebisch P, Wend C, Wellmann A, et al. High incidence of trisomies 1q, 9q, and 11q in multiple myeloma: results from a comprehensive molecular cytogenetic analysis. Leukemia. 2003;17:2535–2537. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cremer WF, Bila J, Buck I, et al. Delineation of distinct subgroups of multiple myeloma and a model for clonal evolution based on interphase cytogenetics. Genes Chromosom Cancer. 2005;44:194–203. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fonseca R, Oken MM, Greipp PR. The t(4;14)(p16.3;q32) is strongly associated with chromosome 13 abnormalities in both multiple myeloma and monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Blood. 2001;98:1271–1272. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.4.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sawyer JR, Waldron JA, Jagannath S, et al. Cytogenetic findings in 200 patients with multiple myeloma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1995;82:41–49. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(94)00284-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang RF, Li CM, Qiu HR, et al. Investigation of chromosome 1 aberrations in patients with multiple myeloma using cIg-FISH method and its significance. Chin Med J. 2010;31:804–808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cigudosa JC, Rao PH, Calasanz MJ, et al. Characterization of non-random chromosomal gains and losses in multiple myeloma by comparative genomic hybridization. Blood. 1998;91:3007–3010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaughnessy JD, Jr, Zhan F, Burington BE, et al. Validated gene expression model of high-risk multiple myeloma is defined by deregulated expression of genes mapping to chromosome 1. Blood. 2007;109:2276–2284. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-038430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Avet-Loiseau H, Attal M, Campion L, et al. Long-term analysis of the IFM 99 trials for myeloma: cytogenetic abnormalities [t(4;14), del(17p), 1q gains] play a major role in defining long-term survival. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1949–1952. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.5726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walker BA, Leone PE, Jenner MW, et al. Integration of global SNP-based mapping and expression arrays reveals key regions, mechanisms, and genes important in the pathogenesis of multiple myeloma. Blood. 2006;108:1733–1734. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-005496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grzasko N, Hus M, Pluta A, et al. Additional genetic abnormalities significantly worsen poor prognosis associated with 1q21 amplification in multiple myeloma patients. Hematol Oncol. 2012 doi: 10.1002/hon.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen LJ, Li JY, Xu W, et al. Molecular cytogenetic aberrations in patients with multiple myeloma studied by interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization. Exp Oncol. 2007;29:116–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]