Abstract

Leaf senescence is the last stage of leaf development and is accompanied by cell death. In contrast to senescence in individual organisms that leads to death, leaf senescence is associated with dynamic processes that include the translocation of nutrients from old leaves to newly developing or storage tissues within the same plant. The onset of leaf senescence is largely regulated by age and internal and external stimuli, which include the plant hormone ethylene. Earlier studies have documented the important role of ethylene in the regulation of leaf senescence. The production of ethylene coincides with the onset of leaf senescence, whereas the application of ethylene to plants induces precocious leaf senescence. Recently, many studies have described the components of ethylene signaling and biosynthetic pathways that are involved in modulating the onset of leaf senescence. Particularly, transcription factors (TFs) integrate ethylene signals with those from environmental and developmental factors to accelerate or delay leaf senescence. This review aims to discuss the regulatory cascade involving ethylene and TFs in the regulation of onset of leaf senescence.

Keywords: AP2/ERF, ethylene, leaf development, leaf senescence, NAC, transcription factor, TCP, WRKY

INTRODUCTION

Leaf senescence occurs alongside color changes in leaves and is an easily visible phenomenon in the life cycle of a plant. Leaf senescence involves degradation of chlorophylls, carbohydrates, lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids and contributes to the mobilization of such nutrients from old leaves to growing or storage tissues. The importance of the efficient regulation of leaf senescence was reported by a study on the domestication of cultivated wheat. Loci tightly linked to the enrichment of several important nutrients in cereal grains encode transcription factors (TFs) that regulate the onset of leaf senescence in ancestral wheat plants (Uauy et al., 2006; Waters et al., 2009). The onset of leaf senescence is largely affected by the age of the plant, but is also influenced by changes in environmental conditions. Ethylene and other plant hormones accelerate or delay leaf senescence so that plants are better able to cope with severe environmental changes and achieve the maximum yield of seed and biomass production (Buchanan-Wollaston et al., 2003; Lim et al., 2007; Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The regulation of the onset of leaf senescence. Leaf senescence occurs alongside color changes from green to yellow and brown. The onset of leaf senescence is affected by the age of the plant, but is also influenced by environmental conditions, developmental cues, ethylene, and other plant hormones. Nutrients derived from senescing leaves are translocated to newly growing or storage tissues within the same plant.

Upon leaf senescence, physiological events progress, which include chlorophyll breakdown, photosynthesis cessation, protein and nucleic acids degradation, catabolites and nutrients transport, and cell death responses, and the genes responsible for each event are dynamically up- or downregulated at the transcriptional level. Earlier studies have identified a group of senescence-associated genes (SAGs) that are induced upon senescence, and recent studies have shown specific roles for SAGs in leaf senescence (Gan and Amasino, 1997; Buchanan-Wollaston et al., 2005; Veyres et al., 2008). Indeed, treating plants with ethylene induces the expression of SAG genes (Jing et al., 2002). Dynamic changes in the expression profile of genes during leaf senescence can be visualized at the transcript and metabolite levels (Lin and Wu, 2004; Buchanan-Wollaston et al., 2005; van der Graaff et al., 2006; Balazadeh et al., 2008; Breeze et al., 2011; Watanabe et al., 2013).

Extensive transcriptome analysis revealed differential expression patterns of various families of TFs during leaf senescence (Lin and Wu, 2004; Buchanan-Wollaston et al., 2005; Breeze et al., 2011). Analysis of the promoters of differentially expressed genes during leaf senescence has found enrichment of certain TF motifs such as, NO APICAL MERISTEM, Arabidopsis TRANSCRIPTION ACTIVATION FACTOR, CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON (NAC), APETALA2/ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR (AP2/ERF), and WRKY families (Breeze et al., 2011). Genetic and molecular studies also provide strong evidence that the activities of NAC, AP2/ERF, WRKY, and several other TF family members influence the onset of leaf senescence (Buchanan-Wollaston et al., 2003; Lim et al., 2007). Significantly, ethylene modulates the activity of these TFs. These findings illustrate that ethylene-mediated modulation of TF activities underlie the onset of leaf senescence.

This review aims to provide a detailed overview of the regulatory cascade involving ethylene and TFs in the regulation of the onset of leaf senescence. This review first provides a brief overview of the role of ethylene in this process and then focuses on the detailed actions of NAC, AP2/ERF, WRKY, and other developmental regulators (Table 1). Emphasis is also placed on how ethylene modulates TF activities and interacts with other hormones during the development of leaf senescence.

Table 1.

Transcription factors (TFs) regulating the onset of leaf senescence.

| Namea | Accession numberb,c,d,e,f | Family | Functiong | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARF2a | AT5G62000b | ARF | Positive | Ellis et al. (2005), Lim et al. (2010) |

| NtERF3 | D38124d | AP2/ERF | Positive | Koyama et al. (2013) |

| AtERF4 | AT3G15210b | AP2/ERF | Positive | Koyama et al. (2013) |

| AtERF8 | AT1G53170b | AP2/ERF | Positive | Koyama et al. (2013) |

| SlERF36 | SGN-U564952c | AP2/ERF | Positive | Upadhyay et al. (2013) |

| RAV1 | AT1G13260b | AP2/ERF | Positive | Woo et al. (2010) |

| GmRAV | NM_001250671d | AP2/ERF | Positive | Zhao et al. (2008) |

| EDF1 | AT1G25560b | AP2/ERF | Negative | Chen et al. (2011) |

| EDF2 | AT1G68840b | AP2/ERF | Negative | Chen et al. (2011) |

| SUB1A | LOC_Os09g11480e | AP2/ERF | Negative | Fukao et al. (2012) |

| CBF2 | AT4G25470b | AP2/ERF | Negative | Sharabi-Schwager et al. (2010) |

| CBF3 | AT4G25480b | AP2/ERF | Negative | Sharabi-Schwager et al. (2010) |

| CRF6 | AT3G61630b | AP2/ERF | Negative | Zwack et al. (2013) |

| CIB | Glyma11g12450f | bHLH | Positive | Meng et al. (2013) |

| EIN3 | AT3G20770b | EIN3 | Positive | Li et al. (2013), Kim et al. (2014) |

| GLK2 | AT5G44190b | GARP | Negative | Rauf et al. (2013) |

| GBF1 | AT4G36730b | GBF | Positive | Smykowski et al. (2010) |

| GAIa | AT1G14920b | GRAS | Negative | Chen et al. (2014) |

| GRF3 | AT2G36400b | GRF | Negative | Debernardi et al. (2014) |

| Knotted1 | AY312169d | homeodomain | Negative | Ori et al. (1999) |

| KNAT2 | AT1G70510b | homeodomain | Negative | Hamant et al. (2002) |

| FYF | AT5G62165b | MADS | Negative | Chen et al. (2011) |

| MYBR1/MYB44 | AT5G67300b | MYB | Negative | Jaradat et al. (2013) |

| NAM-B1 | DQ871219d | NAC | Positive | Uauy et al. (2006) |

| AtNAP | AT1G69490b | NAC | Positive | Guo and Gan (2006), Zhang and Gan (2012) |

| ORE1 | AT5G39610b | NAC | Positive | Kim et al. (2009) |

| ANAC019 | AT1G52890b | NAC | Positive? | Hickman et al. (2013) |

| ANAC055 | AT3G15500b | NAC | Positive? | Hickman et al. (2013) |

| OsNAP | LOC_Os03g21060e | NAC | Positive | Zhou et al. (2013), Liang et al. (2014) |

| ORS1 | AT3G29035b | NAC | Positive | Balazadeh et al. (2011) |

| VNI2 | AT5G13180b | NAC | Negative | Yang et al. (2011) |

| JUB1a | AT2G43000b | NAC | Negative | Wu et al. (2012) |

| TCP2 | AT4G18390b | TCP | Positive | Schommer et al., 2008 |

| TCP3 | AT1G53230b | TCP | Positive | Schommer et al. (2008), Koyama et al. (2013) |

| TCP4 | AT3G15030b | TCP | Positive | Schommer et al. (2008), Koyama et al. (2013) |

| TCP5 | AT5G60970b | TCP | Positive | Koyama et al. (2013) |

| TCP10 | AT2G31070b | TCP | Positive | Schommer et al. (2008), Koyama et al. (2013) |

| TCP13 | AT3G02150b | TCP | Positive | Koyama et al. (2013) |

| TCP19 | AT5G51910b | TCP | Negative | Danisman et al. (2012) |

| TCP20 | AT3G27010b | TCP | Negative | Danisman et al. (2012) |

| TCP24 | AT1G30210b | TCP | Positive | Schommer et al. (2008) |

| WRKY6 | AT1G62300b | WRKY | Positive | Robatzek and Somssich (2002) |

| WRKY53 | AT4G23810b | WRKY | Positive | Miao and Zentgraf (2007) |

| WRKY54 | AT2G40750b | WRKY | Negative | Besseau et al. (2012) |

| WRKY57 | AT1G69310b | WRKY | Negative | Jiang et al. (2014) |

| WRKY70 | AT3G56400b | WRKY | Negative | Besseau et al. (2012) |

| SlZF2 | ADZ15317d | Zn finger | Negative | Hichri et al. (2014) |

aAbbreviations: GIBBERELLIC ACID INSENSITIVE (GAI) and JUNGBRUNNEN1 (JUB1). Other TF names are defined in the main text. b,c,d,e,fAccession numbers: The sequence data can be found in bArabidopsis Genome Initiative, cSol genomic network, dGenbank, eMichigan State University Rice Genome Annotation Project, and fPhytozome libraries. gFunction: Positive and negative indicate TFs that accelerate and delay leaf senescence, respectively.

ETHYLENE AS A REGULATOR OF THE ONSET OF LEAF SENESCENCE

Earlier studies reported the involvement of ethylene in the regulation of leaf senescence. Ethylene production is associated with the onset and progression of leaf senescence in various plant species (Abel et al., 1992). Application of ethylene to leaves stimulates senescence, but inhibitors of ethylene perception or biosynthesis delay leaf senescence (Aharoni and Lieberman, 1979; Kao and Yang, 1983). Furthermore, downregulation of an ethylene biosynthesis gene in tomato plants led to a decrease in ethylene production and substantially delayed leaf senescence, clearly suggesting that ethylene, produced as plants age, accelerates leaf senescence (John et al., 1995).

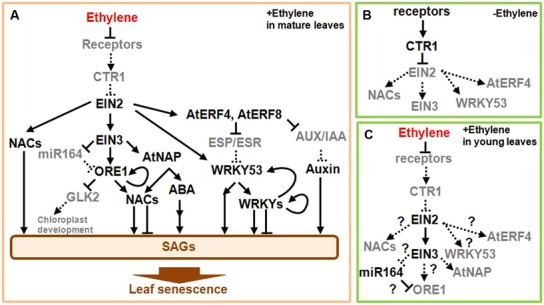

Knowledge of the ethylene signaling pathway will help to clarify the regulatory gene network involved in the onset of leaf senescence. As shown in Figure 2A, receptors localized on the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane detect ethylene (Kendrick and Chang, 2008). Since these receptors repress the activity of downstream signaling components in the absence of ethylene (Figure 2B), ethylene reverses this repression and thus activates the signaling pathway. The signal generated following the detection of ethylene is subsequently transmitted to a complex composed of CONSTITUTIVE TRIPLE RESPONSE1 (CTR1), a Raf-like serine/threonine protien kinase, and ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE2 (EIN2), which is an integral ER membrane protein (Ju et al., 2012; Qiao et al., 2012). In the absence of the ethylene signal, CTR1 directly phosphorylates the cytosolic carboxyl-terminal domain of EIN2 (EIN2-C), whereas the ethylene signal prevents this phosphorylation and results in cleavage of EIN2-C, which then translocates to the nucleus and activates ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE3 (EIN3) and EIN3-LIKE (EIL) TFs. The ethylene signal stabilizes EIN3 and EIL TFs, which are short-lived proteins in the absence of ethylene (Guo and Ecker, 2003; Potuschak et al., 2003), consequently inducing various physiological responses including the onset of leaf senescence.

FIGURE 2.

Scheme of the ethylene signaling pathway leading to the onset of leaf senescence. (A) In mature leaves, the detection of ethylene activates the downstream signaling pathway leading to SAG induction and leaf senescence. (B) In young and mature leaves, the receptors constitutively repress the downstream signaling in the absence of ethylene. (C) In young leaves, the detection of ethylene activates the downstream signaling pathway, but does not itself induce leaf senescence. Note that EIN2 and EIN3 are active and induce some ethylene responses, but not leaf senescence by an uncharacterized mechanism, in which some regulators of leaf development are likely involved. Arrows and bars at the end of each line show positive and negative regulations, respectively. Solid lines and black gene names designate the active form, while dotted lines and gray gene names indicate the inactive form. Several transcription factors (TFs) and signals such as jasmonic acid are not drawn in this scheme owing to space limitations. A detailed description on the scheme is presented in the main text.

Mutations in components of the ethylene signaling pathway exhibit differential timing of the onset of senescence, clearly suggesting that these components are involved in the regulation of such process. Consistent with the repressive role of ethylene receptors including ETHYLENE RESISTANT1 (ETR1) in the signaling pathway, a dominant-negative version of the receptors, such as the etr1 mutation, delays leaf senescence in Arabidopsis and petunia plants (Grbić and Bleecker, 1995; Wang et al., 2013). In contrast, an Arabidopsis null mutant that lacks two of five ethylene receptor genes has a phenotype consistent with constitutive ethylene response as well as accelerated leaf senescence (Qu et al., 2007). A pivotal role of EIN2 in the positive regulation of leaf senescence was documented by characterizing the genetic loci controlling the onset of leaf senescence in Arabidopsis (Oh et al., 1997; Kim et al., 2009). EIN3 positively regulates the onset of leaf senescence, since the ein3 mutant delays leaf senescence whereas overexpression of EIN3 gene accelerates it (Li et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2014). In contrast, the ctr1 mutant does not induce precocious leaf senescence and the involvement of CTR1 in the regulation of leaf senescence remains unclear. (Jing et al., 2005).

ETHYLENE-REGULATED NAC AND OTHER TFs CONTROL THE ONSET OF LEAF SENESCENCE

Several reports have attempted to elucidate the mechanism through which the ethylene signaling pathway modulates NAC activities during the onset of leaf senescence (Kim et al., 2009, 2014; Li et al., 2013; Figure 2A). The NAC TF family includes 105 members in Arabidopsis that are important during development and stress responses (Mitsuda and Ohme-Takagi, 2009). Among NAC genes upregulated during leaf senescence, six NAC genes including ORESARA1 (ORE1)/ANAC092, ANAC019, NAC-like activated by AP3 (AtNAP), ANAC047, ANAC055, and ORE1 SISTER1 (ORS1)/ANAC059 are activated through the EIN2-dependent pathway (Kim et al., 2009, 2014; Figure 2A). ORE1 positively regulates the onset of leaf senescence and activates the expression of ORE1 itself, other NAC, nuclease, a sugar transporter, and various SAG genes (Kim et al., 2009; Balazadeh et al., 2010; Breeze et al., 2011; Matallana-Ramirez et al., 2013; Rauf et al., 2013). ORE1 interacts with GOLDEN-LIKE2 (GLK2), the GARP family TF required for chloroplast development (Rauf et al., 2013). ORE1 attenuates GLK2 activity and may stop the maintenance of chloroplast development. ORE1 activity is modulated at both transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels (Kim et al., 2009; Figure 2A). ORE1 mRNA is targeted by the micro RNA miR164. The decrease in miR164 content with leaf aging is largely dependent on the EIN2 gene and thus leads to the accumulation of ORE1 mRNA in old leaves. Recent studies have further revealed that EIN3 directly activates expression of ORE1 (Li et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2014). Interestingly, EIN3 represses three miR164 precursor genes and is also involved in both positive and indirect regulation of the ORE1 gene (Li et al., 2013). Consistent with the molecular evidence, ORE1 expression is reduced in ein3 mutant during leaf senescence. These observations suggest that EIN3, miR164, and ORE1 comprise a regulatory network that operates downstream of the ethylene signaling pathway (Figure 2A).

Among other NAC genes downstream of EIN2, the AtNAP gene is under the direct control of EIN3, whereas ORS1, ANAC019, ANAC047, and ANAC055 genes are activated in an EIN3-independent manner (Kim et al., 2014; Figure 2A). AtNAP positively regulates the onset of leaf senescence and activates a component of the abscisic acid (ABA) signaling pathway, which promotes both leaf senescence and stress responses (Guo and Gan, 2006; Zhang and Gan, 2012). A rice homolog gene, OsNAP1, acts as a positive regulator of leaf senescence and its product directly targets an ABA biosynthesis enzyme gene (Zhou et al., 2013; Liang et al., 2014). ORS1 positively regulates the onset of leaf senescence (Balazadeh et al., 2011). ANAC019 and ANAC055 seem to function under the control of C-REPEAT/DEHYDRATION RESPONSIVE ELEMENT BINDING FACTORS (CBFs) of AP2/ERF TFs and other TFs during stress response and leaf senescence (Hickman et al., 2013; See below). A role for ANAC047 in leaf senescence is yet to be determined.

Five additional NAC genes including VND-INTERACTING2 (VNI2) are thought to function downstream of ORE1 and AtNAP (Kim et al., 2014). VNI2 negatively regulates the onset of leaf senescence via the direct activation of COLD REGULATED (COR) and RESPONSIVE TO DEHYDRATION (RD) genes that are also responsive to environmental stimuli (Yang et al., 2011). By contrast, the functions of other NAC genes remain to be clarified. The regulation of EIN2, EIN3, NAC TFs, and the ABA response pathway are likely to be important in the integration of various inputs from diverse environmental factors as well as the age of the plant (Figure 2A).

ETHYLENE-RESPONSIVE TFs IN THE REGULATION OF ONSET OF LEAF SENESCENCE

Ethylene activates a substantial number of AP2/ERF genes, and several of these regulate the onset of leaf senescence. The AP2/ERF TFs comprise 146 members that include both activators and repressors of transcription (Mitsuda and Ohme-Takagi, 2009). A subgroup of transcriptional repressors with the ERF-associated repression (EAR) motif, such as NtERF3, AtERF4, and AtERF8, positively regulate the onset of leaf senescence in Arabidopsis (Ohta et al., 2001; Koyama et al., 2013; Figure 2A). The finding of EIN2-dependent AtERF4 expression in leaves suggests that there is AtERF4 activity downstream of EIN2 (Fujimoto et al., 2000). AtERF4 and AtERF8 are degraded by a proteasomal-dependent pathway, but accumulate within the plant as a result of increasing age (Koyama et al., 2013). These ERF TFs directly repress expression of the EPITHIOSPECIFIER PROTEIN/EPITHIOSPECIFYING SENESCENCE REGULATOR (ESP/ESR) gene, a negative regulator of the onset of leaf senescence (Miao and Zentgraf, 2007; Koyama et al., 2013). The ESP/ESR transcript is highly expressed in young leaves, but decreased in old ones (Koyama et al., 2013). ESP/ESR inhibits the activity of WRKY53, a positive regulator of the onset of leaf senescence, at both transcriptional and post-translational levels (Miao and Zentgraf, 2007; See below). These findings imply that AtERF4 and AtERF8 activate WRKY53 by removing the ESP/ESR-mediated inhibition. Therefore, AtERF4, AtERF8, ESP/ESR, and WRKY53 form another regulatory network for the onset of leaf senescence (Figure 2A). Moreover, AtERF4 and AtERF8 repress the expression of AUXIN/INDOLE-3-ACETIC ACID (AUX/IAA) genes. AUX/IAA TFs generally suppress auxin responses that include positive effects on leaf senescence. Therefore, it is possible that the AtERF4- and AtERF8-mediated AUX/IAA repression enhances auxin response and then stimulates the onset of leaf senescence. In addition, a tomato homolog of AtERF4, SlERF36, accelerates leaf senescence when overexpressed in tomato plants (Upadhyay et al., 2013).

By contrast, RAV1 and GmRAV1, which possess another type of repression domain (Ikeda and Ohme-Takagi, 2009), negatively regulate the onset of leaf senescence, because overexpression of these RAV1 genes delays leaf senescence in Arabidopsis (Woo et al., 2010). Other two Arabidopsis RAV genes, namely, ETHYLENE RESPONSE DNA BINDING FACTOR1 (EDF1) and EDF2, are proposed to regulate the onset of leaf senescence downstream of the MADS box TF, FOREVER YOUNG FLOWER (FYF; Chen et al., 2011). These RAV genes are transcriptionally induced by ethylene (Alonso et al., 2003). Based on studies investigating EAR- and RAV-type AP2/ERF TFs, the ethylene signal appears to balance positive and negative regulations thus determining the rate of leaf senescence.

Transcriptional activators of ERF TFs are also involved in regulating the onset of leaf senescence. SUBMERGENCE1A (SUB1A) negatively regulates the onset of leaf senescence in rice (Fukao et al., 2012), while CYTOKININ RESPONSE FACTOR6 (CRF6) negatively regulates leaf senescence (Zwack et al., 2013). Overexpression of CBF2 and CBF3 genes delays leaf senescence in Arabidopsis (Sharabi-Schwager et al., 2010). Since CBFs target COR15 and RD29 genes and possibly control ANAC019 and ANAC055 (Yang et al., 2011; Hickman et al., 2013), CBFs seem to regulate the onset of leaf senescence via these downstream genes. However, there have been no reports on the involvement of ethylene in the regulation of these ERF activators.

WRKY TFs INTEGRATE ETHYLENE AND JASMONIC ACID SIGNALS DURING LEAF SENESCENCE

Jasmonic acid (JA) is another important factor regulating the onset of leaf senescence, because a mutant that lacks a JA-biosynthetic enzyme gene delays leaf senescence and application of JA to leaves accelerates senescence (He et al., 2002; Seltmann et al., 2010). JA often cooperatively interacts with ethylene to underpin many physiological responses (Lorenzo et al., 2004; Zhu et al., 2011). It has been well documented that JA, along with the age of the plant, induce transcription of many WRKY genes. (Lin and Wu, 2004). Among WRKY TFs activated by JA, WRKY53 positively regulates the onset of leaf senescence and its activity is modulated by ESP/ESR at both transcriptional and post-translational levels (Miao and Zentgraf, 2007; Figure 2A). ESP/ESR physically interacts with WRKY53 and, presumably, prevents WRKY53 binding to DNA. ESP/ESR also inhibits the accumulation of WRKY53 transcripts in leaves. It has also been reported that WRKY6, WRKY54, WRKY57, and WRKY75 regulate leaf senescence (Robatzek and Somssich, 2002; Besseau et al., 2012; Li et al., 2012b). Since WRKY6 and WRKY53 have been shown to increase many WRKY transcripts in addition to SAGs (Robatzek and Somssich, 2002; Miao et al., 2004), some self-amplification of WRKY activity may contribute to the robust control of leaf senescence.

Several reports provide intriguing insights into the interactions between WRKY TFs and the ethylene signaling pathway. Nematode-induced WRKY53 expression in leaves requires a functional EIN2 gene, suggesting the involvement of EIN2 in the modulation of WRKY53 activity (Murray et al., 2007). WRKY75 is also involved in the ethylene-dependent defense-signaling pathway (Chen et al., 2013). WRKY33, whose transcript is markedly increased during leaf senescence, directly activates ethylene biosynthetic genes and is involved in ethylene production (Breeze et al., 2011; Li et al., 2012a). Thus, it is possible that WRKY TFs are activated by the cooperative action of the ethylene and JA signaling pathways in the regulation of the onset of leaf senescence.

In addition, the single stranded-DNA binding protein WHIRLY1A and a histone methyltransferase target the WRKY53 gene in Arabidopsis (Ay et al., 2009; Miao et al., 2013). A basic loop-helix-loop TF activates the WRKY53 gene and positively regulates the onset of leaf senescence in soybean (Meng et al., 2013). However, an association between ethylene and these WRKY53 regulators remains to be addressed.

THE ONSET OF LEAF SENESCENCE IS AFFECTED BY TFs THAT ARE REQUIRED FOR LEAF DEVELOPMENT

In contrast to the pivotal role of ethylene in the onset of leaf senescence, it is known that ethylene inhibits leaf expansion in young plants, but does not always induce leaf senescence (Kieber et al., 1993; Hua and Meyerowitz, 1998). Moreover, Arabidopsis ctr1 mutant has constitutive responses to ethylene resulting in the formation of a small rosette, but does not appear to induce precocious leaf senescence (Kieber et al., 1993; Jing et al., 2005). These apparent discrepancies suggest that the mechanism leading to leaf senescence might require some developmental regulators even when the ethylene signaling pathway is activated (Figure 2C). Whereas the functional interaction between ethylene and developmental regulators during leaf senescence is not fully understood, it is expected that such regulators have pivotal roles in the onset of leaf senescence.

KNOTTED1-like homeodomain (KNOX) TFs, which are required for shoot meristem and leaf development, negatively regulate the onset of leaf senescence (Ori et al., 1999; Hamant et al., 2002; Hay and Tsiantis, 2010). When KNOX genes are ectopically expressed in tobacco and Arabidopsis leaves, they markedly delay the onset of leaf senescence (Ori et al., 1999; Hamant et al., 2002). Ectopic KNOX expression confers an undifferentiated cell fate in leaves and inhibits their differentiation (Hay and Tsiantis, 2010). As a consequence, this disordered cellular regulation may indirectly delay the onset of leaf senescence. Otherwise, KNOX TFs regulate biosynthetic genes of cytokinin (Sakamoto et al., 2001; Hay et al., 2002), which acts as a negative regulator of the onset of leaf senescence, and therefore, possibly influences leaf senescence. In agreement with the antagonism between KNOX genes and the gibberellin (GA) signaling pathway observed in shoot meristem and leaf development (Hay and Tsiantis, 2010), plants treated with GA and Arabidopsis mutants of the GRAS-type TF genes, which are negative regulators of the GA signaling pathway, accelerate leaf senescence (Chen et al., 2014).

Another class of regulators for both leaf senescence and development is the TEOSINTE BRANCHED1, CYCLOIDEA, PCNA BINDING FACTOR (TCP) TFs family. A combined analysis of high-resolution temporal clustering of genes differentially expressed during leaf senescence and TF-binding motif searching in the promoters of each cluster demonstrates that the TCP-binding motif is significantly enriched in certain downregulated gene clusters (Breeze et al., 2011). This indicates the co-regulation of these gene clusters and TCP activity. Consistent with bioinformatic surveillance, reverse genetic analysis revealed that inhibition of the CINCINNATA (CIN) subfamily of TCP (CIN-like TCP) delays leaf senescence whereas overexpression of a CIN-like TCP gene accelerates it (Schommer et al., 2008; Koyama et al., 2013). A possible scenario to explain the positive roles of CIN-like TCP TFs in the onset of leaf senescence is that CIN-TCP TFs activate JA biosynthetic enzyme genes (Schommer et al., 2008). Alternatively, CIN-like TCP TFs suppress an auxin signaling pathway, which is a negative regulator of leaf senescence, and also activates negative regulators of KNOX genes (Koyama et al., 2007, 2010). Moreover, CIN-like TCPs act as heterochronic regulators of leaf development and consequently influence the onset of leaf senescence (Efroni et al., 2008). By contrast, TCP19 and TCP20, which are grouped into a class I subgroup, negatively regulate the onset of leaf senescence and results in the opposite effects of CIN-like TCPs (Danisman et al., 2012).

In addition to KNOX and TCP TFs, Arabidopsis GROWTH-REGULATING FACTOR (GRF) TFs and a tomato C2H2 type-EAR repressor regulate both leaf development and senescence (Debernardi et al., 2014; Hichri et al., 2014). Taking the roles of the developmental regulators into account, these regulators, thus, prevent precocious leaf senescence. Ethylene meditates various signals required for the induction of defense responses against biotic and abiotic stressors (Kendrick and Chang, 2008); however, these responses are not always followed by cell death. Therefore, such developmental regulators are likely to determine the fate of leaves upon ethylene exposure. In comparison to fully maturated leaves, young leaves accumulate low amounts of carbon and nitrogen sources that would be mobilized to growing and storage organs and therefore it is reasonable that young leaves are kept away from senescence even in the presence of ethylene.

CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

In addition to ethylene, JA and the developmental signals discussed in this review, additional factors such as cytokinin, auxin, ABA, and hydrogen peroxide are involved in the regulation of leaf senescence (Ellis et al., 2005; Lim et al., 2010; Smykowski et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2012; Jaradat et al., 2013). Several TFs are reported to regulate the onset of leaf senescence under these additional signals and details of such TF are listed in Table 1. Ethylene and these signals are integrated for the regulation of the onset of leaf senescence; however, there have been no reports of a direct interaction between ethylene and such TFs acting downstream of these signals. It is interesting to investigate whether these TFs act in an ethylene-dependent manner during the onset of leaf senescence.

This review focuses on the roles of TFs and ethylene in the regulation of the onset of leaf senescence and emphasizes that regulation occurs at multiple levels downstream of the ethylene signaling pathway. Moreover, leaf development is tightly linked to the onset of senescence and further clarification of such mechanisms is in progress. Furthermore, the effect of ethylene on the stimulation of leaf senescence is dependent on the duration of ethylene exposure (Jing et al., 2005). Regulation of the appropriate duration of ethylene exposure could represent another candidate for modulating the ethylene signal and thus, the onset of leaf senescence. Further efforts to determine the mechanism that transforms the ethylene signal into the onset of leaf senescence will improve our current understanding of the roles of ethylene in leaf senescence.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the study was conducted in the absence of any financial, commercial or other relationships that might be perceived by the academic community as representing a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The author appreciates Drs. Makoto Suematsu and Honoo Satake for helpful comments on the manuscripts. This work is supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 26440158.

REFERENCES

- Abel F. B., Morgan P. W., Saltveit M. S., Jr. (1992) “Regulation of ethylene production by internal, environmental, and stress factors,” in Ethylene in Plant Biology, (San Diego, CA: Academic Press; ), 56–119. [Google Scholar]

- Aharoni N., Lieberman M. (1979). Ethylene as a regulator of senescence in tobacco leaf discs. Plant Physiol. 64 801–804 10.1104/pp.64.5.801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso M., Stepanova A. N., Leisse T. J., Kim C. J., Chen H., Shinn P., et al. (2003). Genome-wide insertional mutagenesis of Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 301 653–657 10.1126/science.1086391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ay N., Irmler K., Fischer A., Uhlemann R., Reuter G., Humbeck K. (2009). Epigenetic programming via histone methylation at WRKY53 controls leaf senescence in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 58 333–346 10.1111/j.1365-3139.2008.03782.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balazadeh S., Kwasniewski M., Caldana C., Mehrnia M., Zanor M. I. Z., Xue G.-P., et al. (2011). ORS1, an H2O2-Responsive NAC transcription factor, controls senescence in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Plant 4 346–360 10.1093/mp/ssq080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balazadeh S., Riaño-Pachón D. M., Mueller-Roeber B. (2008). Transcription factors regulating leaf senescence in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Biol. (Stuttg.) 10 63–75 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2008.00088.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balazadeh S., Siddiqui H., Allu A. D., Matallana-ramirez L. P., Caldana C. (2010). A gene regulatory network controlled by the NAC transcription factor ANAC092/AtNAC2/ORE1 during salt-promoted senescence. Plant J. 62 250–264 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04151.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besseau S., Li J., Palva E. T. (2012). WRKY54 and WRKY70 co-operate as negative regulators of leaf senescence in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 63 2667–2679 10.1093/jxb/err450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breeze E., Harrison E., McHattie S., Hughes L., Hickman R., Hill C., et al. (2011). High-resolution temporal profiling of transcripts during Arabidopsis leaf senescence reveals a distinct chronology of processes and regulation. Plant Cell 23 873–894 10.1105/tpc.111.083345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan-Wollaston V., Earl S., Harrison E., Mathas E., Navabpour S., Page T., et al. (2003). The molecular analysis of leaf senescence – a genomics approach. Plant Biotechnol. J. 1 3–22 10.1046/j.1467-7652.2003.00004.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan-Wollaston V., Page T., Harrison E., Breeze E., Lim P. O., Nam H. G., et al. (2005). Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals significant differences in gene expression and signalling pathways between developmental and dark/starvation-induced senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 42 567–585 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02399.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M., Hsu W., Lee P., Thiruvengadam M., Chen H., Yang C. (2011). The MADS box gene, FOREVER YOUNG FLOWER, acts as a repressor controlling floral organ senescence and abscission in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 68 168–185 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04677.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M., Maodzeka A., Zhou L., Ali E., Wang Z., Jiang L. (2014). Plant science removal of DELLA repression promotes leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant Sci. 219–220, 26–34 10.1016/j.plantsci.2013.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Liu J., Lin G., Wang A., Wang Z., Lu G. (2013). Overexpression of AtWRKY28 and AtWRKY75 in Arabidopsis enhances resistance to oxalic acid and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Plant Cell Rep. 32 1589–1599 10.1007/s00299-013-1469-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danisman S., van der Wal F., Dhondt S., Waites R., de Folter S., Bimbo A., et al. (2012). Arabidopsis class I and class II TCP transcription factors regulate jasmonic acid metabolism and leaf. Plant Physiol. 159 1511–1523 10.1104/pp.112.200303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debernardi J. M., Mecchia M. A., Vercruyssen L., Smaczniak C., Kaufmann K., Inze D., et al. (2014). Post-transcriptional control of GRF transcription factors by microRNA miR396 and GIF co-activator affects leaf size and longevity. Plant J. 79 413–426 10.1111/tpj.12567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efroni I., Blum E., Goldshmidt A., Eshed Y. (2008). A protracted and dynamic maturation schedule underlies Arabidopsis leaf development. Plant Cell 20 2293–2306 10.1105/tpc.107.057521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis C. M., Nagpal P., Young J. C., Hagen G., Guilfoyle T. J., Reed J. W. (2005). AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR1 and AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR2 regulate senescence and floral organ abscission in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development 132 4563–4574 10.1242/dev.02012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto S. Y., Ohta M., Usui A., Shinshi H., Ohme-Takagi M. (2000). Arabidopsis ethylene-responsive element binding factors act as transcriptional activators or repressors of GCC box-mediated gene expression. Plant Cell 12 393–404 10.1105/tpc.12.3.393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukao T., Yeung E., Bailey-serres J. (2012). The submergence tolerance gene SUB1A delays leaf senescence under prolonged darkness through hormonal regulation in rice. Plant Physiol. 160 1795–1807 10.1104/pp.112.207738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan S., Amasino R. M. (1997). Making sense of senescence (molecular genetic regulation and manipulation of leaf senescence). Plant Physiol. 113 313–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grbić V., Bleecker A. B. (1995). Ethylene regulates the timing of leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 8 595–602 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1995.8040595.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H., Ecker J. R. (2003). Plant responses to ethylene gas are mediated by SCF(EBF1/EBF2)-dependent proteolysis of EIN3 transcription factor. Cell 115 667–677 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00969-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y., Gan S. (2006). AtNAP, a NAC family transcription factor, has an important role in leaf senescence. Plant J. 46 601–612 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02723.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamant O., Nogue F., Belles-boix E., Jublot D., Grandjean O., Traas J. (2002). The KNAT2 homeodomain protein interacts with ethylene and cytokinin signaling. Plant Physiol. 130 657–665 10.1104/pp.004564.1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay A., Kaur H., Phillips A., Hedden P., Hake S., Tsiantis M. (2002). The gibberellin pathway mediates KNOTTED1-type homeobox function in plants with different body plans. Curr. Biol. 12 1557–1565 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)01125-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay A., Tsiantis M. (2010). KNOX genes: versatile regulators of plant development and diversity. Development 137 3153–3165 10.1242/dev.030049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y., Fukushige H., Hildebrand D. F., Gan S. (2002). Evidence supporting a role of jasmonic acid in Arabidopsis leaf senescence. Plant Physiol. 128 876–884 10.1104/pp.010843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hichri I., Muhovski Y., Zi E., Dobrev P. I., Franco-zorrilla J. M., Solano R., et al. (2014). The Solanum lycopersicum zinc finger2 cysteine2/histidine2 repressor-like transcription factor regulates development and tolerance to salinity in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 164 1967–1990 10.1104/pp.113.225920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman R., Hill C., Penfold C. A., Breeze E., Bowden L., Moore J. D., et al. (2013). A local regulatory network around three NAC transcription factors in stress responses and senescence in Arabidopsis leaves. Plant J. 75 26–39 10.1111/tpj.12194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua J., Meyerowitz E. M. (1998). Ethylene responses are negatively regulated by a receptor gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana. Cell 94 261–271 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81425-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda M., Ohme-Takagi M. (2009). A novel group of transcriptional repressors in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 50 970–975 10.1093/pcp/pcp048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaradat M. R., Feurtado J. A., Huang D., Lu Y., Cutler A. J. (2013). Multiple roles of the transcription factor AtMYBR1/AtMYB44 in ABA signaling, stress responses, and leaf senescence. BMC Plant Biol. 13:192 10.1186/1471-2229-13-192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Liang G., Yang S., Yu D. (2014). Arabidopsis WRKY57 functions as a node of convergence for jasmonic acid – and auxin-mediated signaling in jasmonic acid – induced leaf senescence. Plant Cell 26 230–245 10.1105/tpc.113.117838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing H., Schippers J. H. M., Hille J., Dijkwel P. P. (2005). Ethylene-induced leaf senescence depends on age-related changes and OLD genes in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 56 2915–2923 10.1093/jxb/eri287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing H., Sturre M. J. G., Hille J., Dijkwel P. P. (2002). Arabidopsis onset of leaf death mutants identify a regulatory pathway controlling leaf senescence. Plant J. 32 51–63 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01400.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John I., Drake R., Farrell A., Cooper W., Lee P., Horton P., et al. (1995). Delayed leaf senescence in ethylene-deficient ACC-oxidase antisense tomato plants: molecular and physiological analysis. Plant J. 7 483–490 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1995.7030483.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ju C., Mee G., Marie J., Lin D. Y., Ying Z. I., Chang J., et al. (2012). CTR1 phosphorylates the central regulator EIN2 to control ethylene hormone signaling from the ER membrane to the nucleus in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111 10013–10018 10.1073/pnas.1214848109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao C. H., Yang F. A. (1983). Role of ethylene in the senescence of detached rice leaves. Plant Physiol. 73 881–885 10.1104/pp.73.4.881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendrick M. D., Chang C. (2008). Ethylene signaling: new levels of complexity and regulation. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 11 479–485 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieber J. J., Rothenberg M., Roman G., Feldmann K. A., Ecker J. R. (1993). CTR1, a negative regulator of the ethylene response pathway in Arabidopsis, encodes a member of the raf family of protein kinases. Cell 72 427–441 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90119-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. J., Hong S. H., Kim Y. W., Lee I. H., Jun J. H., Phee B., et al. (2014). Gene regulatory cascade of senescence-associated NAC transcription factors activated by ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE2-mediated leaf senescence signalling in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 65 4023–4036 10.1093/jxb/eru112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. H., Woo H. R., Kim J., Lim P. O., Lee I. C., Choi S. H., et al. (2009). Trifurcate feed-forward regulation of age-dependent cell death involving miR164 in Arabidopsis. Science 323 1053–1057 10.1126/science.1166386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama T., Furutani M., Tasaka M., Ohme-Takagi M. (2007). TCP transcription factors control the morphology of shoot lateral organs via negative regulation of the expression of boundary-specific genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19 473–484 10.1105/tpc.106.044792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama T., Mitsuda N., Seki M., Shinozaki K., Ohme-Takagi M. (2010). TCP transcription factors regulate the activities of ASYMMETRIC LEAVES1 and miR164, as well as the auxin response, during differentiation of leaves in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 22 3574–3588 10.1105/tpc.110.075598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama T., Nii H., Mitsuda N., Ohta M., Kitajima S., Ohme-Takagi M., et al. (2013). A regulatory cascade involving class II ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR transcriptional repressors operates in the progression of leaf senescence. Plant Physiol. 162 991–1005 10.1104/pp.113.218115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G., Meng X., Wang R., Mao G., Han L., Liu Y., et al. (2012a). Dual-level regulation of ACC synthase activity by MPK3/MPK6 cascade and its downstream WRKY transcription factor during ethylene induction in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 8:e1002767 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Peng J., Wen X., Guo H. (2012b). Gene network analysis and functional studies of senescence-associated genes reveal novel regulators of Arabidopsis leaf senescence. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 54 526–539 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2012.01136.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Peng J., Wen X., Guo H. (2013). Ethylene-insensitive3 is a senescence-associated gene that accelerates age-dependent leaf senescence by directly repressing miR164 transcription in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25 3311–3328 10.1105/tpc.113.113340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang C., Wang Y., Zhu Y., Tang J., Hu B., Liu L., et al. (2014). OsNAP connects abscisic acid and leaf senescence by fine-tuning abscisic acid biosynthesis and directly targeting senescence-associated genes in rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111 10013–10018 10.1073/pnas.1321568111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim P. O., Kim H. J., Nam H. G. (2007). Leaf senescence. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 58 115–136 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim P. O., Lee I. C., Kim J., Kim H. J., Ryu J. S., Woo H. R., et al. (2010). Auxin response factor 2 (ARF2) plays a major role in regulating auxin-mediated leaf longevity. J. Exp. Bot. 61 1419–1430 10.1093/jxb/erq010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J.-F., Wu S.-H. (2004). Molecular events in senescing Arabidopsis leaves. Plant J. 39 612–628 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02160.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo O., Chico J. M., Sa J. J. (2004). JASMONATE-INSENSITIVE1 encodes a MYC transcription factor essential to discriminate between different jasmonate-regulated defense responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 16 1938–1950 10.1105/tpc.022319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matallana-Ramirez L. P., Rauf M., Farage-barhom S., Dortay H., Xue G. (2013). NAC transcription factor ore1 and senescence- constitute a regulatory cascade in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 6 1432–1452 10.1093/mp/sst012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Y., Li H., Wang Q., Liu B., Lin C. (2013). Blue light-dependent interaction between cryptochrome2 and CIB1 regulates transcription and leaf senescence in soybean. Plant Cell 25 4405–4420 10.1105/tpc.113.116590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao Y., Jiang J., Ren Y., Zhao Z. (2013). The single-stranded DNA-binding protein WHIRLY1 represses WRKY53 expression and delays leaf senescence in a developmental stage-dependent manner in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 163 746–756 10.1104/pp.113.223412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao Y., Laun T., Zimmermann P., Zentgraf U. (2004). Targets of the WRKY53 transcription factor and its role during leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. 55 853–867 10.1007/s11103-005-2142-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao Y., Zentgraf U. (2007). The antagonist function of Arabidopsis WRKY53 and ESR/ESP in leaf senescence is modulated by the jasmonic and salicylic acid equilibrium. Plant Cell 19 819–830 10.1105/tpc.106.042705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuda N., Ohme-Takagi M. (2009). Functional analysis of transcription factors in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 50 1232–1248 10.1093/pcp/pcp075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray S. L., Ingle R. A., Petersen L. N., Denby K. J. (2007). Basal resistance against Pseudomonas syringae in Arabidopsis involves WRKY53 and a protein with homology to a nematode resistance protein. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 20 1431–1438 10.1094/MPMI-20-11-1431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh S. A., Park J., Lee G. I., Paek K. H., Park S. K., Nam H. G. (1997). Identification of three genetic loci controlling leaf senescence in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 12 527–535 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1997.00527.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta M., Matsui K., Hiratsu K., Shinshi H., Ohme-Takagi M. (2001). Repression domains of class II ERF transcriptional repressors share an essential motif for active repression. Plant Cell 13 1959–1968 10.1105/tpc.13.8.1959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ori N., Juarez M. T., Jackson D., Yamaguchi J., Banowetz G. M., Hake S. (1999). Leaf senescence is delayed in tobacco plants expressing the maize homeobox gene knotted1 under the control of a senescence-activated promoter. Plant Cell 11 1073–1080 10.1105/tpc.11.6.1073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potuschak T., Lechner E., Parmentier Y., Yanagisawa S., Grava S., Koncz C., et al. (2003). EIN3-dependent regulation of plant ethylene hormone signaling by two Arabidopsis F box proteins: EBF1 and EBF2. Cell 115 679–689 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00968-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao H., Shen Z., Huang S. C., Schmitz R. J., Urich M. A., Briggs S. P., Ecker J. R. (2012). Processing and subcellular trafficking of ER-tethered EIN2 control response to ethylene gas. Science 338 390–393 10.1126/science.1225974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu X., Hall B. P., Gao Z., Schaller G. E. (2007). A strong constitutive ethylene-response phenotype conferred on Arabidopsis plants containing null mutations in the ethylene receptors ETR1 and ERS1. BMC Plant Biol. 7:3 10.1186/1471-2229-7-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauf M., Arif M., Dortay H., Matallana-ram L. P., Waters M. T., Gil Nam H., et al. (2013). ORE1 balances leaf senescence against maintenance by antagonizing G2-like-mediated transcription. EMBO Rep. 14 382–388 10.1038/embor.2013.24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robatzek S., Somssich I. E. (2002). Targets of AtWRKY6 regulation during plant senescence and pathogen defense. Genes Dev. 16 1139–1149 10.1101/gad.222702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto T., Kamiya N., Ueguchi-Tanaka M., Iwahori S., Matsuoka M. (2001). KNOX homeodomain protein directly suppresses the expression of a gibberellin biosynthetic gene in the tobacco shoot apical meristem. Genes Dev. 15 581–590 10.1101/gad.867901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schommer C., Palatnik J. F., Aggarwal P., Chételat A., Cubas P., Farmer E. E., et al. (2008). Control of jasmonate biosynthesis and senescence by miR319 targets. PLoS Biol. 6:e230 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seltmann M. A., Stingl N. E., Lautenschlaeger J. K., Krischke M., Mueller M. J., Berger S. (2010). Differential impact of lipoxygenase 2 and jasmonates on natural and stress-induced senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 152 1940–1950 10.1104/pp.110.153114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharabi-Schwager M., Lers A., Samach A., Guy C. L., Porat R. (2010). Overexpression of the CBF2 transcriptional activator in Arabidopsis delays leaf senescence and extends plant longevity. J. Exp. Bot. 61 261–273 10.1093/jxb/erp300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smykowski A., Zimmermann P., Zentgraf U. (2010). G-Box Binding Factor1 reduces CATALASE2 expression and regulates the onset of leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 153 1321–1331 10.1104/pp.110.157180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Uauy C., Distelfeld A., Fahima T., Blechl A., Dubcovsky J. (2006). A NAC gene regulating senescence improves grain protein, zinc, and iron content in Wheat. Science 314 1298–1301 10.1126/science.1133649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay R. K., Soni D. K., Singh R., Dwivedi U. N., Pathre U. V., Nath P. (2013). SlERF36, an EAR-motif-containing ERF gene from tomato, alters stomatal density and modulates photosynthesis and growth. J. Exp. Bot. 64 3237–3247 10.1093/jxb/ert162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Graaff E., Schwacke R., Schneider A., Desimone M., Kunze R. (2006). Transcription analysis of Arabidopsis membrane transporters and hormone pathways during developmental and induced leaf senescence. Plant Physiol. 141 776–792 10.1104/pp.106.079293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veyres N., Danon A., Aono M., Galliot S., Karibasappa Y. B., Diet A., et al. (2008). The Arabidopsis sweetie mutant is affected in carbohydrate metabolism and defective in the control of growth, development and senescence. Plant J. 55 665–686 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03541.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Liu G., Li C., Powell A. L., Reid M. S., Zhang Z., et al. (2013). Defence responses regulated by jasmonate and delayed senescence caused by ethylene receptor mutation contribute to the tolerance of petunia to Botrytis cinerea. Mol. Plant Pathol. 14 453–469 10.1111/mpp.12017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe M., Balazadeh S., Tohge T., Erban A., Giavalisco P., Kopka J., et al. (2013). Comprehensive dissection of spatiotemporal metabolic shifts in primary, secondary, and lipid metabolism during developmental senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 162 1290–1310 10.1104/pp.113.217380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters B. M., Uauy C., Dubcovsky J., Grusak M. A. (2009). Wheat (Triticum aestivum) NAM proteins regulate the translocation of iron, zinc, and nitrogen compounds from vegetative tissues to grain. J. Exp. Bot. 60 4263–4274 10.1093/jxb/erp257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo H. R., Kim J. H., Kim J., Kim J., Lee U., Song I., et al. (2010). The RAV1 transcription factor positively regulates leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 61 3947–3957 10.1093/jxb/erq206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu A., Allu A. D., Garapati P., Siddiqui H., Dortay H., Zanor M. I., et al. (2012). JUNGBRUNNEN1, a reactive oxygen species-responsive NAC transcription factor, regulates longevity in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24 482–506 10.1105/tpc.111.090894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S.-D., Seo P. J., Yoon H.-K., Park C.-M. (2011). The Arabidopsis NAC transcription factor VNI2 integrates abscisic acid signals into leaf senescence via the COR/RD genes. Plant Cell 23 2155–2168 10.1105/tpc.111.084913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K., Gan S.-S. (2012). An abscisic acid-AtNAP transcription factor-SAG113 protein phosphatase 2C regulatory chain for controlling dehydration in senescing Arabidopsis leaves. Plant Physiol. 158 961–969 10.1104/pp.111.190876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L., Luo Q., Yang C., Han Y., Li W. (2008). A RAV-like transcription factor controls photosynthesis and senescence in soybean. Planta 227 1389–1399 10.1007/s00425-008-0711-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Huang W., Liu L., Chen T., Zhou F., Lin Y. (2013). Identification and functional characterization of a rice NAC gene involved in the regulation of leaf senescence. BMC Plant Biol. 13:1 10.1186/1471-2229-13-132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z., An F., Feng Y., Li P., Xue L., Mu A., et al. (2011). Derepression of ethylene-stabilized transcription factors (EIN3/EIL1) mediates jasmonate and ethylene signaling synergy in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108 12539–12544 10.1073/pnas.1103959108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwack P. J., Robinson B. R., Risley M. G., Rashotte A. M. (2013). Cytokinin response factor 6 negatively regulates leaf senescence and is induced in response to cytokinin and numerous abiotic stresses. Plant Cell Physiol. 54 971–981 10.1093/pcp/pct049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]