Abstract

The current study examined the main effects of hostile attributional bias (HAB) and negative emotional responding on a variety of aggressive behaviors in adults, including general aggression, physical aggression, relational aggression, and verbal aggression. Effects of both externalizing (anger) and internalizing (embarrassment/upset) negative emotions were considered. In addition, the moderating roles of gender and impulsivity on the effects of HAB and negative emotional responding were explored. Multilevel models were fitted to data from 2,749 adult twins aged 20–55 from the PennTwins cohort. HAB was positively associated with all four forms of aggression. There was also a significant interaction between impulsivity and HAB for general aggression. Specifically, the relationship between HAB and general aggression was only significant for individuals with average or above-average levels of impulsivity. Negative emotional responding was also found to predict all measures of aggression, although in different ways. Anger was positively associated with all forms of aggression, whereas embarrassment/upset predicted decreased levels of general, physical, and verbal aggression but increased levels of relational aggression. The associations between negative emotional responding and aggression were generally stronger for males than females. The current study provides evidence for the utility of HAB and negative emotional responding as predictors of adult aggression and further suggests that gender and impulsivity may moderate their links with aggression.

Keywords: hostile attributional bias, negative emotional responding, gender differences, impulsivity, aggression

INTRODUCTION

Aggressive behaviors have serious emotional and social consequences. Associations between aggression and peer rejection, depression, and academic failure have been consistently documented in samples of children and adolescents [Crick et al., 1999; Ostrov and Godleski, 2009]. In adults, aggression is often comorbid with a wide variety of psychiatric conditions and can lead to severe social and economic consequences [Asberg, 1994; Caspi et al., 1998; Coccaro et al., 2009; Friedman and Booth-Kewley, 1987; Riley et al., 1989; Swanson et al., 1990]. Therefore, understanding the etiology of aggressive behaviors has been an important focus in past research [Bailey and Ostrov, 2008].

Information-processing theories were first introduced in 1960s and 1970s to explain a variety of social behaviors, such as decision making and problem solving [e.g., Abelson, 1968; Simon, 1969; Wyer, 1974]. Enlightened by this pioneering work, a number of information-processing models were developed in the 1980s and 1990s to specifically explain individual differences in aggressive behaviors [e.g., Crick and Dodge, 1994; Dodge, 1980; Huesmann, 1982, 1988, 1998]. Overall, these information-processing models highlighted two broad cognitive processes underlying aggressive responses: (1) encoding and interpretation of cues (e.g., attribution of intent); and (2) response assessment and enactment (e.g., evaluation of the likelihood that each alternative will produce the desired outcomes). In particular, hostile attributional bias (HAB) consistently plays a central role across different information-processing theories of aggression [Guerra and Huesmann, 2004; Huesmann, 1998].

HAB, defined as a tendency to interpret the intent of others as hostile when social context cues are ambiguous [Milich and Dodge, 1984], has been viewed as a key element in the etiology of problem behaviors [Orobio de Castro et al., 2002]. According to information-processing perspectives, aggressive individuals make hostile attribution to others’ intent more often than nonaggressive individuals [Dodge, 1980; Huesmann, 1998]. Consistent with this hypothesis, empirical studies routinely find a positive relationship between HAB and aggressive behaviors [e.g., Bailey and Ostrov, 2008; Crick, 1995; Crick et al., 2002; Dodge, 1980; Dodge and Somberg, 1987; Feldman and Dodge, 1987; Hubbard et al., 2001]. In a recent meta-analysis, the relationship between HAB and aggressive behaviors across studies had a weighted mean effect size of r = .17 [Orobio de Castro et al., 2002].

Although the relationship between HAB and aggressive behaviors has been widely examined using child or adolescent samples [e.g., Crick et al., 2002; Crick and Dodge, 1996; Hubbard et al., 2001; see Orobio de Castro et al., 2002 for a review], only a small number of published studies have examined the HAB–aggression link in adult populations [i.e., Bailey and Ostrov, 2008; Barefoot et al., 1989; Basquill et al., 2004; Epps and Kendall, 1995; MacBrayer et al., 2003; Matthews and Norris, 2002; Miller and Lynam, 2006]. Although these studies all supported a positive association between HAB and aggression, findings were based on relatively small samples (ranging from N = 45–263). In addition, the majority of the studies were not conducted on samples of general adult population, but on college students [i.e., Bailey and Ostrov, 2008; Barefoot et al., 1989; Epps and Kendall, 1995; Miller and Lynam, 2006] or adult males with mild mental retardation [i.e., Basquill et al., 2004], which has limited generalizability. Thus, there is a need to further evaluate the role of HAB in the development of aggressive behaviors in large, epidemiologically based samples of adults.

The Role of Emotions in Information-Processing Models of Aggression

Existing research on information-processing models of aggression has largely examined the effects of HAB on aggression without taking the role of emotions into account. Cognitive and emotional processes are interrelated dimensions [Loeber and Coie, 2001] and both HAB and emotion reactions are closely associated key components of information-processing models [Crick and Dodge, 1994; Guerra and Huesmann, 2004; Lemerise and Arsenio, 2000]. Not only can the interpretation of other’s intent as hostile lead to negative emotional responses, but negative emotions in the context of ambiguous social situations may facilitate both hostile attributions and the retrieval of aggressive responses [Berkowitz, 1990; Crick and Dodge, 1994; Huesmann, 1998; Lemerise and Arsenio, 2000].

Empirically, negative emotions have been in general positively associated with both aggressive behaviors [e.g., Arsenion et al., 2000; Cornell et al., 1999; Deater-Deckard et al., 2010; Eisenberg et al., 2009] and hostile attributions of intent [see Lemerise and Maulden, 2010 for a review]. However, previous studies have usually not taken an integrative perspective of HAB and negative emotional responding by examining the effects of these two processes on aggression simultaneously. In addition, the majority of prior work has not consistently differentiated externalizing (e.g., anger) and internalizing (e.g., sadness or embarrassment) negative emotions, although theoretical work suggests that these two forms of negative emotions vary in their functions [Izard and Ackerman, 2000]. For instance, while anger is proposed to lead to increased levels of motor activity, sadness is hypothesized to decelerate the cognitive and motor systems [Izard and Ackerman, 2000]. Thus, an angry emotional response may increase aggressive behaviors, while feelings of embarrassment or upset might actually be associated with lower levels of aggression. The positive association between anger and aggression has been widely supported [e.g., Arsenion et al., 2000; Baker and Bramston, 1997; Cornell et al., 1999; Deater-Deckard et al., 2010; Eisenberg et al., 2009; Fives et al., 2011; Lemery et al., 2002; Murray-Close et al., 2010; Peled and Moretti, 2007, 2010; Sprague et al., 2011]; however, only a handful of studies have examined the role of sadness in aggression and findings from these studies are mixed. While there is evidence that sadness is inversely related to aggression [Peled and Moretti, 2007, 2010; Zeman et al., 2002], other studies have found a positive relationship between sadness and externalizing behavioral problems [Eisenberg et al., 2002, 2009; Lemery et al., 2002]. Furthermore, previous research on anger or sadness has been focused largely on childhood or adolescence, with limited attention paid to aggressive behaviors in adulthood [c.f., Baker and Bramston, 1997; Murray-Close et al., 2010; Peled and Moretti, 2010; Sprague et al., 2011].

Gender Differences in Aggression and Information Processing

It has been well established that males tend to engage in more aggressive behaviors than females [e.g., Block, 1983; Crick and Grotpeter, 1995; Parke and Slaby, 1983]. Prior studies suggest that part of the difference in frequency of aggression between males and females may be due to gender differences in information processing and responses. For example, previous research has found that males are more likely to externalize negative affect and respond with anger/aggression, while females tend to internalize their responses [e.g., Ogle et al., 1995; Taylor et al., 2000; Verona and Curtin, 2006]. Men are also less able to regulate their behavioral responses to emotional evocations than women [Knight et al., 2002]. Similarly, there is evidence that unpleasant or aversive events, such as interpersonal provocation or frustration, are more likely to trigger externalizing responses in men than in women [Verona and Curtin, 2006]. These studies suggest that the effects of HAB and negative emotional responding on aggression may be stronger among males; however, this hypothesis has not been tested explicitly in prior studies.

Impulsivity, Aggression, and Information Processing

Aggressive behaviors can be explained by both cognitively controlled factors as well as automatic and thoughtless processes, such as impulsivity [Berkowitz, 2008], defined as a tendency to act on the spur of the moment or to respond quickly to a given stimulus, without deliberation and evaluation of consequences [Buss and Plomin, 1975; White et al., 1994]. Impulsivity has been found to predict aggression both cross-sectionally [e.g., Barry et al., 2007; Campbell and Muncer, 2009; Ferguson et al., 2005; Houston and Stanford, 2005; Raine et al., 2006; Vigil-Colet et al., 2008] as well as longitudinally [e.g., Fite et al., 2008; Luengo et al., 1994; Ostrov and Godlecki, 2009]. Moreover, impulsivity has been associated with multiple forms of aggression, including general aggression [Fite et al., 2008; Houston and Stanford, 2005], verbal aggression [Campbell and Muncer, 2009; Vilgil-Colet et al., 2008], and physical aggression [Campbell and Muncer, 2009; Ferguson et al., 2005; Ostrov and Godlecki, 2009; Vigil-Colet et al., 2008], although its relationship with relational aggression is less clear [Ostrov and Godlecki, 2009].1

Recently, expansions of information-processing models have explicitly proposed that impulsivity may moderate the effects of cognitive and emotional aspects of information processing on aggression [Fontaine and Dodge, 2006]. Specifically, it is hypothesized that, in the context of social situations, response evaluation and decision requires consideration of both the immediate and long-term consequences of a given response. This implies that compared with nonimpulsive individuals, HAB or negative emotional responding are more likely to be associated with aggressive behaviors among impulsive individuals because they are more likely to respond immediately to the negative stimulus without evaluating their responses or considering possible consequences of their behaviors. In contrast, the relationships between HAB or negative emotional responding and aggressive behaviors are hypothesized to be weaker for individuals with low levels of impulsivity because they are more likely to be constrained by the evaluative process of information processing, and are therefore less likely to react in an aggressive way when they make hostile attribution to other’s intent or when they experience negative emotions in a social event.

The moderating effect of impulsivity on the relationship between information processing and aggressive behaviors has only been explored in one empirical study. Fite et al. [2008] examined the moderating effect of impulsivity on the relationship between immediate response evaluation (assessed by endorsement of aggressive responses) and later aggressive behaviors assessed by Child Behavior Checklist [CBCL; Achenbach, 1991] using a sample of 585 adolescents. They found that greater endorsement of aggressive responses measured at age 13 predicted aggressive behaviors assessed from age 14 to age 17. However, the association between response evaluation and aggressive behaviors was moderated by prior levels of impulsivity. Specifically, endorsement of aggressive responses predicted aggressive behaviors for adolescents with high levels of impulsivity but not for adolescents with low levels of impulsivity. Fite et al.’s [2008] work thus provides initial empirical support for the moderating effect of impulsivity on the link between information processing and aggression; however, their work focused exclusively on the evaluation process, and did not consider the effects of impulsivity on associations between attribution of intent or negative emotional responding and aggression.

Heterogeneity of Aggression

The heterogeneous nature of the aggression construct has been widely discussed [e.g., Buss and Perry, 1992; Crick and Grotpeter, 1995; Poulin and Boivin, 2000; Suris et al., 2004]. Previous work has distinguished between both forms [i.e., verbal, physical, and relational aggression; e.g., Buss and Perry, 1992; Crick and Grotpeter, 1995; Ostrov and Godleski, 2009] and functions [i.e., reactive and proactive aggression; e.g., Poulin and Boivin, 2000; Vitaro et al., 1998] of aggressive behaviors. It has been proposed that different forms or functions of aggression are triggered by separate neural control mechanisms [Ramirez and Andreu, 2006] and that different types of aggressive behaviors have different genetic etiologies [e.g., Cates et al., 1993; Coccaro et al., 1997a; Vernon et al., 1999; Yeh et al., 2010]. Different forms of aggression may also have different psychological and social antecedents and sequelae. For example, parental physical punishment and social dominance predict physical aggression, whereas parental psychological control and peer exclusion predict relational aggression [Kuppens et al., 2009; Murray-Close and Ostrov, 2009], and physical aggression, but not relational aggression, has been found to be associated with impulsivity–hyperactivity longitudinally [Ostrov and Godlecki, 2009].

The evidence supporting distinctions between various forms of aggression highlights the importance of considering variations in effects of HAB and negative emotional responding across different forms of aggression. Prior studies have provided evidence for the utility of HAB in the explanation of general aggression [e.g., Epps and Kendall, 1995; Katsurada and Sugawara, 1998; VanOostrum and Horvath, 1997], physical aggression [e.g., Bailey and Ostrov, 2008; Crick et al., 2002; Nelson et al., 2008], and relational aggression [e.g., Bailey and Ostrov, 2008; Crick, 1995; Crick et al., 2002; Godleski and Ostrov, 2010]. There is also evidence that negative emotions, such as anger and sadness, correlate with both overt aggression [e.g., Peled and Moretti, 2007, 2010; Sullivan et al., 2010; Zeman et al., 2002] and relational aggression [Peled and Moretti, 2007, 2010; Sullivan et al., 2010]. However, findings from these studies are primarily based on children or adolescents [c.f., Baily and Ostrov, 2008; Epps and Kendall, 1995; Peled and Moretti, 2010], and therefore more research needs to be done using adult samples. Moreover, none of these studies have considered the moderating effects of gender and impulsivity on processes of intent attributions and emotional responses across different forms of aggression. Finally, although a few studies have compared the functions of hostile attributions or negative emotions in the etiology of physical/overt aggression and relational aggression, no agreement has been reached. While some work revealed that HAB was consistently associated with both physical and relational aggression [i.e., physical aggression was associated with HAB for instrumental provocation contexts and relational aggression was associated with HAB for relational provocation contexts; Bailey and Ostrov, 2007; Crick et al., 2002], work by Nelson et al. [2008] failed to find a relationship between relational intent attributions and relational aggression. Similarly, patterns of associations between negative emotions and different forms of aggression observed in prior studies have not been consistent. Specifically, anger rumination predicted both overt aggression and relational aggression, whereas sadness rumination was associated with the overt but not the relational form of aggression in the studies by Peled and Moretti [2007, 2010]. In contrast, Sullivan et al. [2010] found that sadness regulation coping was related to relational aggression but not physical aggression, and that anger regulation coping accounted for differences in physical aggression but not relational aggression.

The Present Study

In summary, although previous studies have provided substantial empirical support for the relationship between HAB and aggressive behaviors in childhood and adolescence, this link has not been widely tested in adulthood. In addition, despite the importance of negative emotional responding in information-processing models and its connectedness with HAB, few studies have investigated differences in the functions of externalizing versus internalizing negative emotions. Moreover, studies have not examined the importance of HAB and negative emotional responding in the etiology of aggression simultaneously. Furthermore, previous studies have not systematically evaluated whether the associations between these two components of information-processing models and aggression differ for males and females and/or are moderated by individual levels of impulsivity. Finally, prior research has not adequately considered variations in the importance of HAB and negative emotional responding or differences in the moderating effects of gender and impulsivity across different forms of aggression in adulthood.

The present study seeks to address these limitations using a large, population-based sample of adults to test relationships between HAB, externalizing negative emotional responding (i.e., anger), and internalizing negative emotional responding (i.e., embarrassment/upset) with four different forms of aggression (general aggression, physical aggression, relational aggression, and verbal aggression).2 This study further explores whether gender and/or impulsivity moderate associations between HAB, negative emotional responding, and aggression. We predict that (1) HAB and negative emotional responding will independently predict different forms of aggression, although the importance of negative emotional responding may vary for internalizing versus externalizing emotions; (2) the relationships between HAB and negative emotional responding with aggression will be stronger for males than females; and (3) the relationships between HAB and negative emotional responding with aggression will be stronger for individuals with higher levels of impulsivity.

METHODS

Sample and Procedures

Participants in the current study are from the PennTwins Cohort, a population-based sample of twins born in Pennsylvania between 1959 and 1978. Full details of the cohort development can be found in Coccaro and Jacobson [2006]. In brief, beginning in 1996, an initial list of 77,012 individuals who were likely to be part of a twin pair was extracted from computerized birth records kept by the Division of Vital Statistics at the Pennsylvania Department of Health. This list was then cross-referenced with active driving license records on file with the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation, resulting in an address list of 30,801 individuals. Of these 30,801 individuals, 9,341 returned consent-to-contact forms. Differences on various demographic characteristics (e.g., age, race/ethnicity, household income) between individuals who consented to participate and those who were unresponsive or could not be located were negligible and nonsystematic [Coccaro and Jacobson, 2006].

Twins who consented to participate in the PennTwins cohort were mailed a brief questionnaire containing basic demographic questions as well as standard twin similarity items. A total of 7,282 twins returned this questionnaire (a response rate of ~76%). The Behavioral Health Questionnaire (BHQ) was then sent to all twin pairs in which both twins had returned the previous questionnaire. The response rate to the BHQ was between 70% and 75%. The BHQ contains a battery of personality and behavioral measures, including the impulsivity, HAB, negative emotional responding, and aggression measures examined in the current study. BHQ data are currently available for 3,070 participants. Missing data were processed with listwise deletion, which resulted in a final study sample of N = 2,749 participants who were between 20 and 55 years of age (89.5% of the sample). The average age of the sample was 33.2 (SD = 6.0). There were slightly more females (58.4%) than males.

Measures

Measures of age, gender, and SES were included in the current study as control variables. Impulsivity, HAB, and measures of negative emotional responding (i.e., anger and embarrassment/upset) were used as the primary predictors of four forms of aggression: general aggression, physical aggression, relational aggression, and verbal aggression.

Gender

For the current analyses, gender was coded as 0 = female and 1 = male.

SES

Participants’ social economic status (SES) was measured by their current family income. Responses were given as 1 = less than $15,000, 2 = $15,000 to $24,999, 3 = $25,000 to $49,999, 4 = $50,000 to $75,000, 5 = $75,000 to $99,999, and 6 = more than $100,000. On average, participants in the present study had a family income between $50,000 and $75,000.

Impulsivity

Impulsivity was measured with the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale version 11 [BIS-11; Patton et al., 1995]. The BIS-11 is a 30-item self-report questionnaire designed to assess participants’ general impulsiveness. Items asked respondents to rate statements describing how they think and behave in general (e.g., “I plan tasks carefully”). Responses were given on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = rarely/never to 4 = almost always/always). A scale score was computed using the sum of the responses of all 30 items (α = .82 for both males and females).

Information processing (hostile attributional bias and negative emotional responding)

Measures of HAB and negative emotional responding were assessed with the Social Information Processing-Attribution and Emotional Response Questionnaire [SIP-AEQ; Coccaro, Noblett, and McCloskey, 2009]. Based on similar protocols used in studies of children [Crick, 1995; Crick et al., 2002; Fite et al., 2008; Lansford et al., 2010], the SIP-AEQ consists of written descriptions of eight vignettes designed specifically for adults. Four vignettes represent direct aggressive scenarios (e.g., being “hit” by someone) and four represent relational aggressive scenarios (e.g., being “rejected” by someone).

Each vignette was followed by four questions that assess direct hostile intent (e.g., “This person wanted to physically hurt me”), indirect hostile intent (e.g., “This person wanted to make me look bad”), instrumental nonhostile intent (e.g., “This person wanted to win the match”), and neutral or benign intent (e.g., “This person did this by accident”). Responses were given in a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = not at all likely to 3 = very likely. The scale score for HAB was computed by summing the responses of the 16 questions (two for each vignette) that assessed direct and indirect hostile intent (α = .87 for both males and females). The correlation between direct and indirect hostile intent was .77 (P < .001) across all eight vignettes.

Each of the vignettes was also followed by two items designed to reflect negative emotional responding including anger (i.e., “How likely is it that you would be angry if this happened to you?”) and embarrassment or upset (i.e., “How likely is it that you would be embarrassed if this happened to you?”). The negative emotional responding items were also measured using a 4-point Likert scale (i.e., 0 = not at all likely to 3 = very likely). The anger (male: α = .80; female: α = .80) and embarrassment/upset (male: α = .81; female: α = .79) scores were created using the sum of the responses to the eight items assessing each form of negative emotional responding, respectively.

General aggression

General aggression was measured by the aggression subscale of the Lifetime History of Aggression Questionnaire [LHA, Coccaro et al., 1997b]. The aggression subscale of LHA (LHA-AGG) contains five items related to adult frequency of temper tantrums, general fighting, specific physical assault, specific property assault, and verbal assault (e.g., “Since you were 18 years old, how many times had you gotten into physical fights with other people”). Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale, based on the total number of occurrences of a given behavior since age 18 (0 = no occurrences, 1 = one occurrence, 2 = two or three occurrences, 3 = four to nine occurrences, 4 = ten or more occurrences, and 5 = more occurrences than can be counted). Initial development of the LHA-AGG indicated good concurrent validity, internal consistency, inter-rater reliability, and test–retest reliability [Coccaro et al., 1997b]. The general aggression score was computed by summing the responses of the five items (α = .75; for both males and females).

Physical aggression

Physical aggression was assessed with the nine-item physical aggression subscale of the Buss–Perry Aggression Questionnaire [BPAQ; Buss and Perry, 1992]. Participants were asked to rate how well each item described themselves (e.g., “Once in a while, I can’t control the urge to hit another person”). Responses were given on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = extremely uncharacteristic of me to 5 = extremely characteristic of me. The physical aggression score was computed by summing the responses of the nine items (male: α = .82; female: α = .80). As the score distribution of the physical aggression was modestly skewed (skewness = 1.07), this variable was transformed using natural log-transformation.

Relational aggression

Relational aggression was measured with 11 items from the Self-Report of Aggression and Social Behavior Measure (SRASBM) developed by Morales and Crick [1998]. Five items assess proactive relational aggression (e.g., “I have threatened to share private information about my friends with other people in order to get them to comply with my wishes”). Six items assess reactive relational aggression (e.g., “When I am not invited to do something with a group of people, I will exclude those people from future activities”). In the present study, the response scale was adapted from the original 7-point Likert scale to range from 0 = never to 4 = very often. The scale score of relational aggression was created by summing the responses of the 11 items (male: α = .84; female: α = .79).3 This variable was also transformed with natural log-transformation as its distribution was skewed (skewness = 1.37).

Verbal aggression

Verbal aggression was measured using the five-item verbal aggression subscale from the BPAQ [Buss and Perry, 1992]. Participants were asked to rate verbal aggression behaviors using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = extremely uncharacteristic of me to 5 = extremely characteristic of me (e.g., “I can’t help getting into arguments when people disagree with me”). The verbal aggression score was computed using the sum of the item responses (male: α = .74; female: α = .71).

Plan of Analyses

Research questions for the current study were tested using a multilevel hierarchical regression analysis in SPSS [Peugh and Enders, 2005]. Because the sample consists of twins, a multilevel modeling strategy was used in order to take into account the clustering of the observations within families. Specifically, participants were identified by their own personal ID and by the family ID they shared with their co-twins. By incorporating the family ID as a random effect, the variance in aggression can be decomposed into variance attributable to differences between individuals (level 1), and variance due to differences between families (level 2), the latter of which are accounted for by the random effect [Teachman and Crowder, 2002]. All study constructs were assessed at the individual level (level 1). The multilevel approach thus accounts for the clustered data and allows the model to produce accurate standard errors and significance tests for individual-level (level-1) effects while controlling for family-level (level-2) variations [Papp, 2004].

A series of five hierarchical models was specified for each measure of aggression. First, an unconditional means model was fitted to compute the proportion of variability in each measure of aggression that existed between individuals and families (Model 1). Second, a model with only age, gender, and SES was specified (Model 2). In Model 3, the main effects of impulsivity, HAB, anger, and embarrassment/upset were tested simultaneously net the effects of the control variables. Next, Model 4 tested the moderating effects of gender on the relationships between impulsivity, HAB, anger, embarrassment/upset, and measures of aggression (i.e., gender × impulsivity, gender × HAB, gender × anger, gender × embarrassment/upset). Finally, the interaction between impulsivity and HAB and the interactions between impulsivity and measures of negative emotional responding were examined in Model 5 (impulsivity × HAB, impulsivity × anger, impulsivity × embarrassment/upset).4

Age and SES were centered using grand mean centering. For interpretation purposes, measures of impulsivity, HAB, and measures of negative emotional responding and aggression were standardized so that regression coefficients could be compared within models and across outcome measures. Hierarchical models were compared using change in log-likelihood (−2LL) statistics, which follows a χ2 distribution. A significant decrease in −2LL indicates that the test model fit significantly better than the comparison model. Significant interactions were plotted and interpreted using methods outlined by Preacher et al. [2006]. Briefly, this method is based on calculation of simple slopes at different levels of the moderator variables as outlined in Aiken and West [1991], but is specifically designed for interpretation of interaction terms with clustered data.

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Table I shows descriptive statistics for the main study variables. Findings based on one-way ANOVA indicated that on average, males reported higher levels of HAB, general aggression, physical aggression, relational aggression, and verbal aggression, and lower levels of anger and embarrassment/upset than females. The between-gender difference in levels of impulsivity was not statistically significant.

TABLE I.

Descriptive Statistics for Impulsivity, Hostile Attributional Bias (HAB), Negative Emotional Responding, and Aggression Measures

| Scales | Total sample (N = 2,749)

|

Males (N = 1,144)

|

Females (N = 1,605)

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Min. | Max. | Mean | SD | Min. | Max. | Mean | SD | Min. | Max. | |

| Impulsivity | 63.11 | 9.75 | 37.00 | 104.00 | 62.95 | 9.64 | 39.00 | 100.00 | 63.22 | 9.83 | 37.00 | 104.00 |

| HABa | 14.66 | 5.94 | .00 | 39.00 | 15.08 | 5.91 | .00 | 36.00 | 14.36 | 5.94 | .00 | 39.00 |

| Angera | 14.04 | 3.64 | .00 | 24.00 | 13.76 | 3.64 | .00 | 24.00 | 14.25 | 3.62 | .00 | 24.00 |

| Embarrassment/Upseta | 11.44 | 4.16 | .00 | 24.00 | 10.55 | 4.11 | .00 | 24.00 | 12.07 | 4.09 | .00 | 24.00 |

| General aggressiona | 7.55 | 4.53 | .00 | 25.00 | 8.20 | 4.64 | .00 | 25.00 | 7.09 | 4.39 | .00 | 25.00 |

| Physical aggressiona | 16.54 | 6.30 | 9.00 | 44.00 | 18.54 | 6.56 | 9.00 | 44.00 | 15.11 | 5.70 | 9.00 | 41.00 |

| Relational aggressiona | 5.13 | 4.32 | .00 | 38.00 | 5.71 | 4.74 | .00 | 38.00 | 4.72 | 3.94 | .00 | 24.00 |

| Verbal aggressiona | 12.77 | 3.83 | 5.00 | 25.00 | 13.49 | 3.81 | 5.00 | 24.00 | 12.25 | 3.75 | 5.00 | 25.00 |

Note: Descriptive statistics of unadjusted (i.e., untransformed and unstandardized) variables were reported in the table.

Between-gender differences in means were statistically significant for these variables based on findings from the one-way ANOVA.

Table II exhibits the Pearson correlations between impulsivity, HAB, the two measures of negative emotional responding, and aggression, by gender. There were statistically significant and positive relationships between all four measures of aggression and impulsivity (r = .19–.33), HAB (r = .10–.31), and anger (r = .15–.34). Embarrassment/upset was significantly and positively correlated with general aggression (r = .09–.14) and was strongly related to relational aggression (r = .24–.30). Embarrassment/upset did not significantly correlate with verbal aggression. In addition, embarrassment/upset had a significant and positive relationship with physical aggression for females (r = .12) but not for males. Finally, measures of HAB, anger, and embarrassment/upset were strongly correlated (r = .44–.51), whereas they were only modestly related to impulsivity (r = .10–.17).

TABLE II.

Correlation Between Impulsivity, Hostile Attributional Bias (HAB), Negative Emotional Responding, and Aggression Measures

| Female

|

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | ||||||||

| 1. Impulsivity | .17** | .11** | .16** | .29** | .33** | .24** | .26** | |

| 2. HAB | .10** | .47** | .45** | .17** | .30** | .31** | .15** | |

| 3. Anger | .11** | .44** | .48** | .19** | .24** | .32** | .15** | |

| 4. Embarrassment/upset | .14** | .51** | .51** | .14** | .12** | .24** | − .04 | |

| 5. General aggression | .23** | .18** | .26** | .09* | .53** | .33** | .34** | |

| 6. Physical aggression | .23** | .19** | .23** | .04 | .53** | .32** | .44** | |

| 7. Relational aggression | .19** | .30** | .34** | .30** | .30** | .26** | .30** | |

| 8. Verbal aggression | .24** | .10** | .19** | − .01 | .35** | .38** | .25** |

Note:

P < .01;

P < .001. Correlation statistics between adjusted variables were reported in the table.

Multilevel Modeling

Hierarchical, multilevel modeling strategies were utilized to predict measures of aggression. Findings from these models for each form of aggression are reported separately in Tables III–VI.

TABLE III.

Multilevel Regression Predicting General Aggression by Impulsivity, Hostile Attributional Bias (HAB), and Negative Emotional Responding

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effecta | |||||

| Intercept | .00 | − .08** | − .08** | − .09*** | − .09*** |

| Male | .20*** | .19*** | .18*** | .18*** | |

| Age | .02*** | .02*** | .02*** | .02*** | |

| SES | − .06*** | − .03 | − .03 | − .03 | |

| HAB | .07*** | .06* | .06* | ||

| Anger | .18*** | .13*** | .13*** | ||

| Embarrassment/upset | − .05* | .01 | .01 | ||

| Impulsivity | .23*** | .24*** | .25*** | ||

| Male × HAB | .04 | .04 | |||

| Male × Anger | .13** | .13** | |||

| Male × Embarrassment/upset | − .14*** | − .15*** | |||

| Male × Impulsivity | − .02 | − .03 | |||

| Impulsivity × HAB | .05* | ||||

| Impulsivity × Anger | .01 | ||||

| Impulsivity × Embarrassment/upset | − .02 | ||||

| Random effect | |||||

| Residual (level 1) | .64*** | .64*** | .59*** | .59*** | .59*** |

| Intercept (level 2) | .36*** | .33*** | .28*** | .27*** | .29*** |

| Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) | .64 | ||||

| Model fit | |||||

| −2LL | 7,653.41 | 7,588.46 | 7,284.42 | 7,267.87 | 7,259.79 |

| Comparison modelb | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Δ−2LL | 64.954*** | 304.04*** | 16.55** | 8.08* | |

| Δdf | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | |

| Variance explained | |||||

| Level 1 | 0% | 8% | 8% | 8% | |

Note:

P < .05;

P < .01;

P < .001.

All variables included in the model are level-1 variables.

Log-likelihood statistics (i.e., −2LL) were compared between the present model and the comparison mode.

TABLE VI.

Multilevel Regression Predicting Verbal Aggression by Impulsivity, Hostile Attributional Bias (HAB), and Negative Emotional Responding

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effecta | |||||

| Intercept | .00 | − .15** | − .12** | − .12** | − .12** |

| Male | .37** | .30** | .31** | .31** | |

| Age | − .01** | − .01* | − .01* | − .01** | |

| SES | − .05** | − .02 | − .02 | − .02 | |

| HAB | .10** | .13** | .13** | ||

| Anger | .17** | .15** | .15** | ||

| Embarrassment/upset | − .19** | − .21** | − .21** | ||

| Impulsivity | .23** | .24** | .24** | ||

| Male × HAB | − .07 | − .07 | |||

| Male × Anger | .06 | .06 | |||

| Male × Embarrassment/upset | .06 | .06 | |||

| Male × Impulsivity | − .02 | − .03 | |||

| Impulsivity × HAB | .02 | ||||

| Impulsivity × Anger | − .01 | ||||

| Impulsivity × Embarrassment/upset | − .01 | ||||

| Random effect | |||||

| Residual (level 1) | .68** | .67** | .63** | .63** | .63** |

| Intercept (level 2) | .32** | .30** | .23** | .23** | .23** |

| ICC | .68 | ||||

| Model fit | |||||

| −2LL | 7,689.29 | 7,587.07 | 7,306.06 | 7,299.77 | 7,298.17 |

| Comparison modelb | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Δ−2LL | 102.22** | 281.01** | 6.29 | 1.60 | |

| Δdf | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | |

| Variance explained | |||||

| Level 1 | 1% | 7% | 8% | 8% | |

Note:

P < .01;

P < .001.

All variables included in the model are level-1 variables.

Log-likelihood statistics (i.e., −2LL) were compared between the present model and the comparison model.

Unconditional model (Model 1)

Variance components of the unconditional model (Model 1) revealed statistically significant variability in all measures of aggression between individuals (σ2 = .62–.70, P < .001). The intraclass correlation coefficient indicated that 62% (physical aggression) to 70% (relational aggression) of the variance in measures of aggression existed between individuals. Statistically significant variability of aggression between twin pairs was also found (τ00 = .30–.38, P < .001), which provided support for using multilevel modeling strategies to take into account the nested nature of the data in the current study.

Control model (Model 2)

Age, gender, and SES were entered as control variables in Model 2. Model 2 had a significantly better fit than the baseline model for all forms of aggression [see Tables III–VI]. Based on Model 2, males were more likely to show higher levels of general aggression (β = .20, P < .001), physical aggression (β = .59, P < .001), relational aggression (β = .20, P < .001), and verbal aggression (β = .37, P < .001) than females. Age was significantly related to general aggression (β = .02, P < .001) and inversely associated with verbal aggression (β = −.01, P < .001), although the magnitudes of the relationships were small. SES had weak negative relationships with general aggression (β = −.06, P < .001) and verbal aggression (β = −.05, P < .001) and was weakly and positively associated with physical aggression (β = .09, P < .001).

Main effect models (Model 3)

The main effect models had a significantly better fit than the control model for all measures of aggression (see Tables III–VI]. In the main effect models, higher levels HAB and impulsivity were consistently associated with higher levels of aggression (HAB: β = .07–.17, P < .001; impulsivity: β = .16–.23, all P < .001). Similarly, anger was significantly and positively associated with all measures of aggression (β = .17–.20, all P < .001). However, different patterns were observed for embarrassment/upset. Specifically, embarrassment/upset was negatively associated with general aggression (β = −.05, P < .05), physical aggression (β = −.12, P < .001), and verbal aggression (β = −.19, P < .001); in contrast, it had a significantly positive relationship with relational aggression (β = .07, P < .001).

Interactions with gender (Model 4)

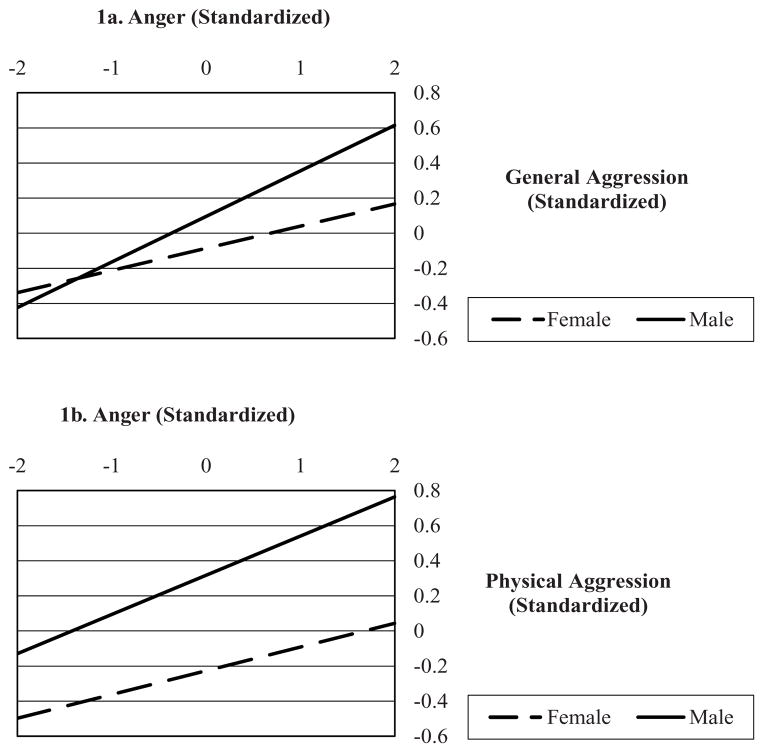

There were no interactions between gender and HAB for any of the four aggression measures. However, results from Model 4 indicate that gender moderated the effects of anger on general aggression (β = .13, P < .01) and physical aggression (β = .09; P < .05). The moderating effects of gender are plotted in Figure 1. Simple slopes were calculated separately for males and females. Anger was significantly and positively associated with general and physical aggression for both males (general aggression: β = .26, P < .001; physical aggression: β = .22, P < .001) and females (general aggression: β = .13, P < .001; physical aggression: β = .14, P < .001), although the relationships were stronger for males (Fig. 1). There was no interaction between gender and anger for relational or verbal aggression.

Fig. 1. Prototypical plot for moderating effects of gender on anger–aggression links.

Note: Simple slopes were significant for both females and males.

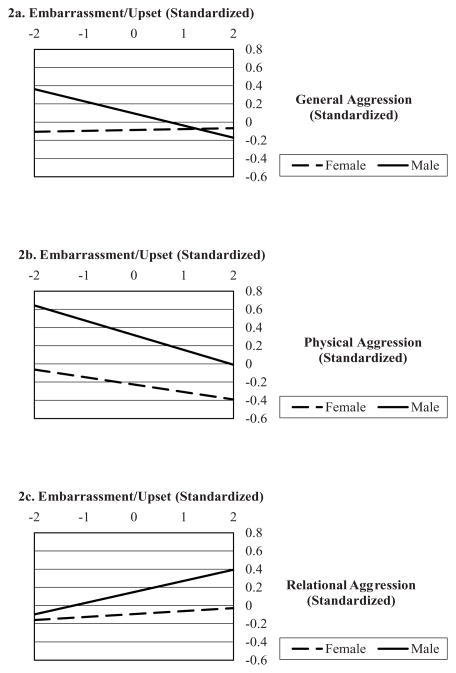

In addition, significant interactions between gender and embarrassment/upset were found for general aggression (β = −.14, P < .001), physical aggression (β = −.08; P < .05), and relational aggression (β = .09; P < .05). Simple slopes calculated for males and females depicting these interactions are shown in Figure 2. For general aggression, there was an inverse correlation between embarrassment/upset for males (β = −.13, P < .001), but the relationship between embarrassment/upset and general aggression was not significant for females (β = .01, P = .72; Fig. 2). For physical aggression, the inverse correlation with embarrassment/upset was significantly stronger in males (β = −.16, P < .001) than females (β = −.08, P < .01; Fig. 2). A different pattern emerged for relational aggression (Fig. 2), where embarrassment/upset was associated with increased levels of relational aggression (β = .12, P < .001) for males, but was not significantly associated with relational aggression in females (β = .03, P = .23). Gender did not moderate the effects of embarrassment/upset on verbal aggression.

Fig. 2. Prototypical plot for moderating effects of gender on embarrassment/upset–aggression links.

Note: Simple slopes of general aggression and relational aggression were not significant for females. All the other simple slopes were significant.

Moderating effects of impulsivity (Model 5)

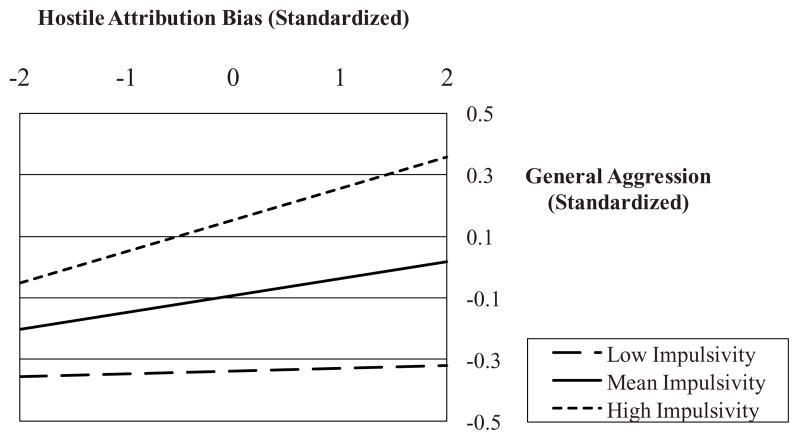

Model 5 revealed a significant interaction effect between impulsivity and HAB, but only for general aggression (β = .05, P < .05). None of the interactions between impulsivity and either measure of negative emotional responding were statistically significant.

To explore the significant interaction between impulsivity and HAB, we plotted the relationships between HAB and general aggression as a function of different levels of impulsivity (see Fig. 3). The simple slopes of HAB were estimated at a low level of impulsivity (i.e., 1 SD below the sample mean), the mean level of impulsivity, and a high level of impulsivity (i.e., 1 SD above the sample mean). The plot was generated within −2 to +2 standard deviations of HAB. Positive relationships between HAB and general aggression were found for individuals with the mean (β = .06, P < .05) and high levels (β = .10, P < .01) of impulsivity. However, the relationship between HAB and general aggression was not significant for individuals with the low level of impulsivity (β = .01, P = .79). Therefore, the relationship between HAB and general aggression was stronger for individuals with higher levels of impulsivity. Significant region tests indicated that the positive relationship between HAB and general aggression was statistically significant for individuals with a standardized impulsivity score above −.05 in the present study. In other words, there was no relationship between HAB and general aggression among participants who had below-average levels of impulsivity.

Fig. 3. Prototypical plot for moderating effect of impulsivity on the hostile attributional bias–general aggression link.

Note: Simple slopes were significant for individuals with the mean and high levels of impulsivity but not for individuals with the low level of impulsivity.

DISCUSSION

The current study examined the relationships between HAB, negative emotional responding, and various forms of aggression (i.e., general aggression, physical aggression, relational aggression, and verbal aggression) in a large sample of adults aged 20–55. The present work extends previous research in three important ways. First, the current study examined the importance of HAB and negative emotional responding in the etiology of adult aggression simultaneously, and further considered the functions of both externalizing (anger) and internalizing (embarrassment/upset) forms of negative emotional responding. Second, the study investigated the moderating effects of gender and impulsivity on the relationships between HAB, negative emotional responding, and measures of aggression. Finally, the current study systematically explored the functions of HAB and negative emotional responding, as well as the moderating effects of gender and impulsivity, across different forms of aggression in the same study.

Negative Emotional Responding, Gender, and Aggression

Previous studies have reported associations between externalizing negative emotions, such as anger, and aggression, in children, adolescents, and adults [e.g., Arsenion et al., 2000; Baker and Bramston, 1997; Cornell et al., 1999; Deater-Deckard et al., 2010; Fives et al., 2011; Murray-Close et al., 2010; Sprague et al., 2011]. Consistent with findings from these studies, we found positive main effects for angry emotional responses and all four forms of aggression. Importantly, our study provided evidence for independent effects of anger on aggression controlling for the cognitive process of HAB. In addition, males were less likely than females to indicate an angry response to ambiguous social stimulations. Nevertheless, as hypothesized, the relationships between an angry response and both general and physical aggression were significantly stronger in males than females. These findings replicate prior studies showing that males are more likely to externalize their anger than women [Ogle et al., 1995; Taylor et al., 2000; Verona and Curtin, 2006].

Although embarrassment/upset was weakly and positively associated with general and physical aggression in the correlational analyses, once hostile attributions and anger were controlled for, we found that the embarrassment/upset form of negative emotional responding was inversely related to these two forms of aggression. Likewise, regression models revealed that embarrassment/upset was also negatively associated with verbal aggression. Although none of the prior studies of emotional responding specifically examined the function of embarrassment/upset in the etiology of aggression, sadness, which is another internalizing form of negative affect, has been implicated in theoretical models and empirical studies of information processing and aggression. From the functionalist perspectives, sadness is thought to slow cognitive and motor systems. Thus, individuals may be better able to process social cues, plan their behaviors more carefully, and to generate more adaptive behavioral responses when they experiences sadness [Izard and Ackerman, 2000]. Our results demonstrating that increased embarrassment/upset was related to lower levels of general, physical, and verbal aggression are therefore consistent with this hypothesis and in support of findings from some of the previous research on sadness [Peled and Moretti, 2007, 2010; Zeman et al., 2002]. Similar to the results for anger, however, the inverse relationship between embarrassment/upset and general and physical aggression was stronger in males than females, despite the fact that males endorsed embarrassment/upset responses less often than females. The stronger relationships between both forms of negative emotional responding and aggression in males found in the current study imply that emotions may play a more salient role in the etiology of aggressive behaviors for males than for females.

Finally, we found yet a different pattern for the relationship between internalizing negative emotional responding and relational aggression. First, the positive correlation between embarrassment/upset and aggression was markedly stronger for relational aggression (r = .24–.30) than for the other three forms of aggression (r = −.04 to .14). Even after controlling for anger and HAB in the regression analyses, higher levels of embarrassment/upset were associated with higher levels of relational aggression, but only among males. This discrepancy of results across different forms of aggression may be related to the hypothesis that sadness triggers a unique social need, namely strengthening social bonds [Sullivan et al., 2010; Witherington and Crichton, 2007]. As one of the social functions of relational aggression is to strengthen social connections and to build social status, engaging in relational aggression may satisfy, at least in the short term, the sadness-driven need to connect with others, although it may ultimately undermine social relationships [Conway, 2005; Izard and Ackerman, 2000; Sullivan et al., 2010; Underwood, 2003].

The difference in results for associations between internalizing emotional responses and relational aggression is also partially consistent with Sullivan et al.’s study [2010], which found an inverse relationship between sadness regulation coping and relational aggression. This implies that dysregulated expression of internalizing negative emotions may be a risk factor for relational aggression. Furthermore, their finding that sadness regulation coping did not predict the physical form of aggression suggests that the role of internalizing emotional responding in the etiology of physical aggression may not be as salient as its role in relational aggression. The gender differences further suggest that while feelings of embarrassment/upset may not be a risk factor in the etiology of female aggression, this form of negative emotional responding may increase males’ tendency to engage in relational aggression, consistent with the hypothesis that aggressive behaviors in males are more sensitive to emotional cues.

Given the complexity of the relationships between different forms of negative emotional responding and aggression, as well as differences in the moderating effects of gender, it is clear that the associations between negative emotional responding and aggression cannot be summarized simply using one hypothesis. Moreover, as only a limited number of studies have examined the effects of internalizing negative emotions, such as sadness, across different forms of aggression [Peled and Moretti, 2007, 2010; Sullivan et al., 2010], we cannot rule out the possibility that the differences between embarrassment/upset across the various types of aggressive behaviors may be stochastic. Nevertheless, findings from the current study highlight the importance of considering externalizing and internalizing negative emotions as separate constructs that may have varying effects on aggression. Future theoretical and empirical work needs to take into account variations in the moderating effects of gender across different forms of negative emotions and aggression.

Hostile Attributional Bias and Aggression

The current study found significant independent main effects of HAB on aggression, even after controlling for negative emotional responding. Our results are consistent with prior studies using younger samples that have shown that highly aggressive children and adolescents are more likely to make more hostile attributions to other people’s intent than their nonaggressive peers [Bailey and Ostrov, 2008; Crick, 1995; Crick et al., 2002; Dodge, 1980; Dodge and Somberg, 1987; Hubbard et al., 2001]. Moreover, in contrast to our results with negative emotional responding, the effects of HAB on aggression were consistent for males and females, as well as across the different forms of aggression. Thus, our study indicates that models of HAB that have been used to explain social behaviors in childhood and adolescence are widely applicable to studies of adult aggression.

On the other hand, we also found a significant interaction between HAB and impulsivity for general aggression, where the positive relationship between HAB and general aggression was weaker at lower levels of impulsivity, and HAB was not significantly associated with general aggression for individuals with below-average levels of impulsivity. Our findings that HAB predicted general aggression only among individuals with average or higher levels of impulsivity are consistent with Fontaine and Dodge’s [2006] conceptual model of information processing and aggression. According to their model, the response evaluation and decision step of information processing is a very complex process that requires at least some degree of active cognitive processing. These cognitive processes may be bypassed among individuals with higher levels of impulsivity, as impulsive processing is characterized by immediate gratification and little executive control. Individuals who make hostile attribution to other’s intent may therefore be more likely to react aggressively when they have higher levels of impulsivity, as impulsive people are less likely to evaluate alternative responses and think about the consequences of their behaviors. On the other hand, HAB may not be as strongly associated with aggression for nonimpulsive individuals, as these individuals are capable of engaging in the complicated response evaluation and decision step, and their behaviors are therefore constrained by the cognitive process. Our findings are also consistent with the only previous study of moderating effects of impulsivity on relationships between information processing and aggressive behaviors [Fite et al., 2008], despite the fact that the prior study focused on response evaluation, rather than attribution of intent, as the cognitive measure of information processing. Findings of the present study therefore suggest that the moderating effect of impulsivity on the relationship between information processing and aggression may generalize across developmental periods, and may further generalize across different components of information processing.

It should be noted that the interaction effect between hostile attribution biases and impulsivity was only significant for general aggression and not for physical, relational, and verbal aggression. As the current study is the very first to examine the moderating effects of impulsivity on the associations between hostile attributional bias, negative emotional responding, and different forms of aggression, it is possible that the significant interaction with impulsivity might be stochastic. While findings of the current study clearly warrant replication in other samples of adults, they do highlight the need to compare the moderating effect of impulsivity on different components of information processing, and to examine this effect across different forms of aggression.

CONCLUSION AND LIMITATIONS

Results from the current study support the importance of HAB and negative emotional responding in the development of individual differences in aggression among adults. In addition, our study provides evidence that externalizing and internalizing negative emotional responding are differentially related to aggression. Finally, the current study provides at least partial support for the hypotheses that gender and impulsivity moderate the effects of HAB and negative emotional responding on different forms of aggression. It is worth noting that the current effort is an important initial step but not a definitive study of the research questions addressed. Patterns observed in the present study need future replications before any firm conclusions could be drawn.

In addition, a number of study limitations require mention. First, findings from the current study were based on cross-sectional data; therefore causality cannot be inferred. For example, it is possible that more aggressive adults are more likely to experience social rejection, and are therefore more inclined to make hostile attributions to other’s intent. Future work therefore needs to replicate findings from the present study using longitudinal data that span adulthood. In addition, the present study only taps into one cognitive process and one emotional component of the comprehensive information-processing models. Thus, the importance of other cognitive (response evaluation) and emotional (e.g., emotion regulation) processes involved in information processing in the etiology of adult aggression and the potential moderating effects of gender and impulsivity on these processes are unknown. Third, given the complexity of the aims of the present study, we did not consider the potential moderating effects of contextual factors on the associations between hostile attribution bias, negative emotional responding, and aggression. However, we acknowledge the importance of the contextual effects, and therefore we are currently exploring how environmental factors (e.g., childhood maltreatment) may interact with HAB and negative emotional responding to predict aggression using the same sample. Finally, the present study did not take the provocation contexts (i.e., instrumental vs. relational provocation contexts) into account when examining the effects of HAB on different forms of aggression. Recent work has found that physical aggression is more strongly associated with HAB in instrumental provocation situations, whereas relational aggression is more strongly associated with HAB in relational provocation scenarios [Bailey and Ostrov, 2008; Crick et al., 2002]. Despite these limitations, findings from the current study suggest that in order to thoroughly capture the complex relationships between HAB, negative emotional responding, and aggression, research needs to consider the moderating effects of gender and impulsivity, as well as distinctions across various forms of negative emotions and different types of aggression.

TABLE IV.

Multilevel Regression Predicting Physical Aggression by Impulsivity, Hostile Attributional Bias (HAB), and Negative Emotional Responding

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effecta | |||||

| Intercept | .00 | − .24*** | − .22*** | − .23*** | − .23*** |

| Male | .59*** | .55*** | .54*** | .54*** | |

| Age | − .00 | − .00 | − .00 | − .00 | |

| SES | .09*** | − .05*** | − .05*** | − .06*** | |

| HAB | .17*** | .20*** | .20*** | ||

| Anger | .17*** | .14*** | .14*** | ||

| Embarrassment/upset | − .12*** | − .08** | − .08** | ||

| Impulsivity | .22*** | .25*** | .25*** | ||

| Male × HAB | − .06 | − .06 | |||

| Male × Anger | .09* | .09* | |||

| Male × Embarrassment/upset | − .08* | − .08* | |||

| Male × Impulsivity | − .06 | − .07 | |||

| Impulsivity × HAB | .01 | ||||

| Impulsivity × Anger | .01 | ||||

| Impulsivity × Embarrassment/upset | − .01 | ||||

| Random effect | |||||

| Residual (level 1) | .62*** | .60*** | .54*** | .54*** | .54*** |

| Intercept (level 2) | .38*** | .30*** | .22*** | .22*** | .24*** |

| ICC | .62 | ||||

| Model fit | |||||

| −2LL | 7,633.87 | 7,378.56 | 6,985.56 | 6,971.41 | 6,970.08 |

| Comparison modelb | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Δ−2LL | 255.31*** | 393.00*** | 14.15** | 1.33 | |

| Δdf | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | |

| Variance explained | |||||

| Level 1 | 3% | 12% | 12% | 12% | |

Note:

P < .05;

P < .01;

P < .001.

All variables included in the model are level-1 variables.

Log-likelihood statistics (i.e., −2LL) were compared between the present model and the comparison model. Genders were found to moderate the effects by impulsivity and HAB on physical aggression when the interaction terms male × impulsivity and male × HAB were tested separately. It was found that the positive relationship between HAB and physical aggression and the relationship between impulsivity and physical aggression were significant for both males (HAB: β = .13, P < .001; impulsivity: β = .18, P < .001) and females (HAB: β = .20, P < .001; impulsivity: β = .25, P < .001), however the relationships were stronger for females.

TABLE V.

Multilevel Regression Predicting Relational Aggression by Impulsivity, Hostile Attributional Bias (HAB), and Negative Emotional Responding

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effecta | |||||

| Intercept | − .00 | − .09*** | − .10*** | − .09*** | − .10*** |

| Male | .20*** | .23*** | .24*** | .24*** | |

| Age | − .00 | − .00 | − .00 | − .00 | |

| SES | − .02 | .02 | .02 | .02 | |

| HAB | .15*** | .16*** | .17*** | ||

| Anger | .20*** | .20*** | .19*** | ||

| Embarrassment/upset | .07*** | .03 | .03 | ||

| Impulsivity | .16*** | .17*** | .16*** | ||

| Male × HAB | − .04 | − .04 | |||

| Male × Anger | .01 | .01 | |||

| Male × Embarrassment/upset | .09* | .09* | |||

| Male × Impulsivity | − .02 | − .02 | |||

| Impulsivity × HAB | .01 | ||||

| Impulsivity × Anger | − .02 | ||||

| Impulsivity × Embarrassment/upset | .03 | ||||

| Random effect | |||||

| Residual (level 1) | .70*** | .70*** | .64*** | .63*** | .63*** |

| Intercept (level 2) | .30*** | .29*** | .19*** | .19*** | .19*** |

| ICC | .70 | ||||

| Model fit | |||||

| −2LL | 7,701.32 | 7,675.59 | 7,209.95 | 7,204.63 | 7,200.36 |

| Comparison modelb | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Δ−2LL | 25.73*** | 465.64*** | 5.32 | 4.27 | |

| Δdf | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | |

| Variance explained | |||||

| Level 1 | 0% | 9% | 10% | 10% | |

Note:

P < .05;

P < .001.

All variables included in the model are level-1 variables.

Log-likelihood statistics (i.e., −2LL) were compared between the present model and the comparison model.

Acknowledgments

Drs. Chen and Jacobson were partially supported by an NIH Director’s New Innovator Award (DP2 OD003021) to Dr. Jacobson.

Grant sponsor: National Institute of Mental Health; Grant number: R01 MH063262.

Footnotes

It was found in Ostrov and Godlecki’s [2009] study that impulsivity–hyperactivity predicted relational aggression cross-sectionally but not longitudinally.

As previous studies focused largely on general aggression [Orobio de Castro et al., 2002], this form of aggression is also examined in the current study.

Additional analyses compared results for proactive and reactive relational aggression (results available from the author). As no meaningful differences were observed, these findings are not reported, and the total relational aggression score is used in the present study.

The interactions between HAB and measures of negative emotional responding as well as the three-way and four-way interactions among gender, HAB, measures of negative emotional responding, and impulsivity (i.e., gender × HAB × anger, gender × HAB × embarrassment/upset, gender × HAB × impulsivity, gender × anger × impulsivity, gender × embarrassment/upset × impulsivity, HAB × anger × impulsivity, HAB × embarrassment/upset × impulsivity, gender × HAB × anger × impulsivity, gender × HAB × embarrassment/upset × impulsivity) were also tested. However, as no significant interaction effects were found, these higher order interactions are omitted from the current analyses.

References

- Abelson RP. Simulation of social behavior. In: Lindzey G, Aronson E, editors. Handbook of Social Psychology. II. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1968. pp. 274–356. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4–18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken L, West S. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Arsenio WF, Cooperman S, Lover A. Affective predictors of preschoolers’ aggression and peer acceptance: Direct and indirect effects. Dev Psychol. 2000;36:438–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asberg M. Monomamine neurotransmitters in human aggressiveness and violence: A selective review. Crim Behav Ment Health. 1994;4:303–327. [Google Scholar]

- Baker W, Bramston P. Attritional and emotional determinants of aggression in people with mild intellectual disabilities. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 1997;2:169–185. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey C, Ostrov J. Differentiating forms and functions of aggression in emerging adults: Associations with hostile attribution biases and normative beliefs. J Youth Adolesc. 2008;37(6):713–722. [Google Scholar]

- Barefoot JC, Dodge KA, Peterson BL, Dahlstrom WG, Williams RB. The Cook–Medley hostility scale: Item content and ability to predict survival. Psychosom Med. 1989;51:46–57. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198901000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry C, Frick P, Adler K, Grafeman S. The predictive utility of narcissism among children and adolescents: Evidence for a distinction between adaptive and maladaptive narcissism. J Child Fam Stud. 2007;16(4):508–521. [Google Scholar]

- Basquill M, Nezu C, Nezu A, Klein T. Aggression-related hostility bias and social problem-solving deficits in adult males with mental retardation. Am J Ment Retard. 2004;109(3):255–263. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2004)109<255:AHBASP>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz L. On the formation and regulation of anger and aggression: A cognitive-neoassociationistic analysis. Am Psychol. 1990;45(4):494–503. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.4.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz L. On the consideration of automatic as well as controlled psychological processes in aggression. Aggress Behav. 2008;34(2):117–129. doi: 10.1002/ab.20244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block J. Differential premises arising from differential socialization of the sexes: Some conjectures. Child Dev. 1983;54(6):1335–1354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss A, Perry M. The aggression questionnaire. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1992;63(3):452–459. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss A, Plomin R. A Temperament Theory of Personality Development. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Interscience; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell A, Muncer S. Can ‘risky’ impulsivity explain sex differences in aggression? Pers Indiv Diff. 2009;47(5):402–406. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Newman DL, Silva PA. Behavioral observations at age 3 years predict adult psychiatric disorders: Longitudinal evidence from a birth cohort. In: Herzig ME, Farber EA, editors. Annual Progress in Child Psychiatry and Child Development. Bristol, PA: Brunner/Mazel Inc; 1998. pp. 319–331. [Google Scholar]

- Cates DS, Houston BK, Vavak CR, Crawford MH, Uttley M. Heritability of hostility-related emotions, attitudes, and behaviors. J Behav Med. 1993;16:237–256. doi: 10.1007/BF00844758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coccaro EF, Bergerman C, Kavoussi RJ, Seroczynski A. Heritability of aggression and irritability: A twin study of the Buss—Durkee Aggression Scales in adult male subjects. Biol Psychiatry. 1997a;41(3):273–284. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(96)00257-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coccaro EF, Berman ME, Kavoussi RJ. Assessment of life history of aggression: Development and psychometric characteristics. Psychiatry Res. 1997b;73:147–157. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(97)00119-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coccaro EF, Jacobson KJ. PennTwins: A population-based cohort for twin studies. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2006;9(6):998–1005. doi: 10.1375/183242706779462633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coccaro E, Noblett K, McCloskey M. Attributional and emotional responses to socially ambiguous cues: Validation of a new assessment of social/emotional information processing in healthy adults and impulsive aggressive patients. J Psychiatr Res. 2009;43(10):915–925. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway AM. Girls, aggression, and emotion regulation. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2005;75:334–339. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.75.2.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornell DG, Peterson CS, Richards H. Anger as a predictor of aggression among incarcerated adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:108–115. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick N. Relational aggression: The role of intent attributions, feelings of distress, and provocation type. Dev Psychopathol. 1995;7(2):313–322. [Google Scholar]

- Crick N, Dodge K. A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychol Bull. 1994;115(1):74–101. [Google Scholar]

- Crick N, Dodge K. Social information-processing mechanisms in reactive and proactive aggression. Child Dev. 1996;67:993–1002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick N, Grotpeter J. Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child Dev. 1995;66(3):710–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick N, Grotpeter J, Bigbee M. Relationally and physically aggressive children’s intent attributions and feelings of distress for relational and instrumental peer provocations. Child Dev. 2002;73(4):1134–1142. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick N, Werner N, Casas J, O’Brien K, Nelson D, Grotpeter J, Markon K. Childhood aggression and gender: A new look at an old problem. In: Bernstein D, editor. Gender and Motivation. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press; 1999. pp. 75–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Beekman C, Wang Z, Kim J, Petrill S, Thompson L, DeThorne L. Approach/positive anticipation, frustration/anger, and overt aggression in childhood. J Pers. 2010;78:991–1010. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00640.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge K. Social cognition and children’s aggressive behavior. Child Dev. 1980;51(1):162–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge K, Somberg D. Hostile attributional biases among aggressive boys are exacerbated under conditions of threats to the self. Child Dev. 1987;58(1):213–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1987.tb03501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Sadovsky A, Spinrad TL, Fabes RA, Losoya SH, Valiente C, Shepard SA. The relations of problem behavior status to children’s negative emotionality, effortful control, and impulsivity: Concurrent relations and prediction of change. Dev Psychol. 2005;41:193–211. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.1.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Valiente C, Spinrad TL, Cumberland A, Liew J, Reiser M, Losoya SH. Longitudinal relations of children’s effortful control, impulsivity, and negative emotionality to their externalizing, internalizing, and co-occurring behavior problems. Dev Psychol. 2009;45:988–1008. doi: 10.1037/a0016213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epps J, Kendall PC. Hostile attributional bias in adults. Cogn Ther Res. 1995;19:159–178. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman E, Dodge K. Social information processing and sociometric status: Sex, age, and situational effects. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1987;15(2):211–227. doi: 10.1007/BF00916350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson CJ, Averill PM, Rhoades H, Rocha D, Gruber N, Gummattira P. Social isolation, impulsivity and depression as predictors of aggression in a psychiatric inpatient population. Psychiatr Q. 2005;76:123–137. doi: 10.1007/s11089-005-2335-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fite J, Goodnight J, Bates J, Dodge K, Pettit G. Adolescent aggression and social cognition in the context of personality: Impulsivity as a moderator of predictions from social information processing. Aggress Behav. 2008;34(5):511–520. doi: 10.1002/ab.20263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fives CJ, Grace K, Ryan FJ, Raymond D. Anger, aggression, and irrational beliefs in adolescents. Cogn Ther Res. 2011;35:199–208. [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine R, Dodge K. Real-time decision making and aggressive behavior in youth: A heuristic model of response evaluation and decision (RED) Aggress Behav. 2006;32(6):604–624. doi: 10.1002/ab.20150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman HS, Booth-Kewley S. The ‘disease-prone personality’. A meta-analytic view of the construct. Am Psychol. 1987;42:439–455. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.42.6.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godleski SA, Ostrov JM. Relational aggression and hostile attribution biases: Testing multiple statistical methods and models. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2010;38:447–458. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9391-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra NG, Huesmann LR. A cognitive-ecological model of aggression. Rev Int Psychol Soc. 2004;2:177–204. [Google Scholar]

- Houston R, Stanford M. Electrophysiological substrates of impulsiveness: Potential effects on aggressive behavior. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005;29(2):305–313. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard J, Dodge K, Cillessen A, Coie J, Schwartz D. The dyadic nature of social information processing in boys’ reactive and proactive aggression. J Person Soc Psychol. 2001;80(2):268–280. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.80.2.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huesmann LR. Information processing models of behavior. In: Hirschberg N, Humphreys L, editors. Multivariate Applications in the Social Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1982. pp. 261–288. [Google Scholar]

- Huesmann LR. An information processing model for the development of aggression. Aggress Behav. 1988;14:13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Huesmann LR. The role of social information processing and cognitive schema in the acquisition and maintenance of habitual aggressive behavior. In: Geen R, Donnerstein E, editors. Human Aggression. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1998. pp. 73–109. [Google Scholar]

- Izard CE, Ackerman BP. Motivational, organizational, and regulatory functions of discrete emotions. In: Lewis M, Haviland-Jones JM, editors. Handbook of Emotions. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2000. pp. 253–264. [Google Scholar]

- Katsurada E, Sugawara AI. The relationship between hostile attributional bias and aggressive behavior in preschoolers. Early Child Res Q. 1998;13:623–636. [Google Scholar]

- Knight G, Guthrie I, Page M, Fabes R. Emotional arousal and gender differences in aggression: A meta-analysis. Aggress Behav. 2002;28(5):366–393. [Google Scholar]

- Kuppens S, Grietens H, Onghena P, Michiels D. Associations between parental control and children’s overt and relational aggression in a sample of Flemish elementary school children. Br J Dev Psychol. 2009;27(3):607–623. doi: 10.1348/026151008x345591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Malone PS, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates J. Developmental cascades of peer rejection, social information processing biases, and aggression during middle childhood. Dev Psychopathol. 2010;22:593–602. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemerise E, Arsenio W. An integrated model of emotion processes and cognition in social information processing. Child Dev. 2000;71(1):107–118. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemerise E, Maulden J. Emotions and social information processing: Implication for understanding aggressive (and non-aggressive) children. In: Arsenio W, Lemerise E, editors. Emotions, Aggression, and Moral Development: Bridging Development and Psychopathology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010. pp. 157–176. [Google Scholar]

- Lemery KS, Essex MJ, Smider NA. Revealing the relation between temperament and behavior problem symptoms by eliminating measurement confounding: Expert ratings and factor analyses. Child Dev. 2002;73:867–882. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Coie J. Continuities and discontinuities of development, with particular emphasis on emotional and cognitive components of disruptive behaviour. In: Hill J, Maughan B, editors. Conduct Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2001. pp. 379–407. [Google Scholar]

- Luengo M, Otero J, Carrillo-de-la-Peña M, Mirón L. Dimensions of antisocial behaviour in juvenile delinquency: A study of personality variables. Psychol Crime Law. 1994;1(1):27–37. [Google Scholar]

- MacBrayer EK, Milich R, Hundley M. Attributional biases in aggressive children and their mothers. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112:698–708. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews B, Norris F. When is believing ‘seeing’? Hostile attribution bias as a function of self-reported aggression. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2002;32(1):1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Milich R, Dodge KA. Social information processing in child psychiatric populations. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1984;12:471–490. doi: 10.1007/BF00910660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J, Lynam D. Reactive and proactive aggression: Similarities and differences. Pers Indiv Diff. 2006;41(8):1469–1480. [Google Scholar]

- Morales JR, Crick NR. Unpublished measure. Twin Cities Campus, MN: University of Minnesota; 1998. Self-Report Measure of Aggression and Victimization. [Google Scholar]