Abstract

As interest grows in the diffusion of evidence-based interventions (EBIs), there is increasing concern about how to mitigate implementation challenges; this paper concerns adapting an EBI for homeless women. Complementing earlier focus groups with homeless women, homeless service providers (n = 32) were engaged in focus groups to assess capacity, needs, and barriers with implementation of EBIs. Deductive analyses of data led to the selection of four EBIs. Six consensus groups were then undertaken; three each with homeless women (n = 24) and homeless service providers (n = 21). The selected EBI was adapted and pretested with homeless women (n = 9) and service providers (n = 6). The structured consensus group process provided great utility and affirmed the expertise of homeless women and service providers as experts in their domain. Engaging providers in the selection process reduced the structural barriers within agencies as obstacles to diffusion.

Keywords: Evidence-based practice, homelessness, women's health, HIV/AIDS prevention

One third of the estimated 43,000 homeless people in Los Angeles County are women.1 Residential instability has been associated with increased risk, including substance use and unsafe sex.2-4 Homeless women are most often at risk of HIV infection through engagement in risky sexual behaviors with men.5,6 Because of these behaviors and the increased likelihood of homeless women to engage in transactional sex,7,8 adapting evidence-based interventions (EBIs) focused on HIV risk reduction among homeless women is imperative.

As interest grows in the diffusion of effective HIV risk reduction interventions, there has been increasing concern about how to mitigate implementation challenges. Efforts to diffuse evidence-based interventions in diverse community settings have been described by others; some focused on increasing fidelity of implementation,9-13 whereas others evaluated outcomes and procedures.14-16 Community practitioners can provide valuable information about which EBIs might be most readily diffused and target populations can determine which EBIs best meet their needs. Considering the viewpoint of clients in decision-making can provide context-specific feedback for EBI implementation. In order to translate and implement EBIs that account for specific community needs and capacity effectively, collaborating with stakeholders (community members, leaders, and experts) at all stages of implementation is essential.17 The current study used the CDC MAP18 and ADAPT-ITT19 frameworks to explore community-specific contexts for HIV prevention among homeless women in Los Angeles. It engaged homeless service providers and homeless women in focus and consensus groups to assess capacity, needs, barriers, and past experiences with similar interventions and select and adapt an EBI for translation to meet the specific needs of homeless women.

Diffusion of efficacious HIV behavioral intervention

During the past decade, substantial research has established the efficacy of several HIV risk reduction interventions; most success occurred among strategies implemented under highly controlled conditions. However, research on the diffusion of these interventions into the community has been limited and remains a primary public health issue.20 It is only when HIV prevention interventions are disseminated effectively that it can be confidently concluded that they have reduced HIV risks.21 In response to the need to translate HIV risk reduction EBIs, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) synthesized interventions identified as highly effective.22 The Diffusion of Effective Behavioral Interventions (DEBI) program is designed to facilitate the dissemination of HIV prevention interventions to community service providers free of cost; the goal is to increase diffusion and implementation of these interventions with fidelity.21-23 Improving capacity for implementation is key to effective translation.

The CDC MAP18 and ADAPT-ITT19 are models that serve as guides to the EBI adaption process. The CDC MAP outlines three distinct phases (assessment, preparation, and implementation) that include the following action steps: assess, select, prepare, pilot, and implement. 18 Inclusion of the target population, stakeholders, and organization employees is recommended. In addition to the assessment, selection (or decision), and preparation (or administration) phases of CDC MAP18, ADAPT-ITT19 more clearly details the inclusion of topical experiences, integration, and training before the testing (pilot) phase. 19 Elements from both models highlight the need for a phased approach to adaptation and the inclusion of diverse stakeholders throughout the process.

Use of these models (among others) has led to cumulative knowledge of issues such as addressing the need for technical support,9 creating a culturally appropriate adaptation of an intervention,24 examining implementation fidelity,10,11 diffusing innovations through training,13 and building community capacity.12 Engaging with the community to adapt interventions is no longer seen as a “one-way transfer” but rather as a “multidimensional technology and information exchange” that emphasizes engagement to exchange knowledge.25[p.6] The process recognizes the need to acknowledge the perspectives of community members and nurture involvement of community practitioners in the adaptation of interventions.

Involvement of stakeholders in EBI implementation

Involvement of stakeholders is recognized as valuable and seen most often during the formative stages of intervention adaptation. However, this involvement should occur at all stages of selection and adaptation of an EBI and should include expanding stakeholder roles to determining specificity and feasibility of implementing the intervention.17 This collaboration not only enables the development of more relevant interventions but also increases acceptability.26 Gandelman, DeSantis, and Rietmeijer27 stressed the importance of assessing community needs and capacity before deciding which EBI is best for a community and suggested guidelines for assessment. These types of needs assessments, if they occur, are not commonly reported in the literature. Developing an intervention with greater understanding of the community context increases the likelihood of its effectiveness and sustainability.27 Key community members can serve as experts on the target issue, reflecting their own values, treatment preferences, and treatment goals;28 participation leads to successful translation and outcomes.29-30

The nominal consensus group has significant utility in exploratory stages of research31 and has advantages over other qualitative decision-making methods due to its greater structure.32 Nominal consensus groups involve a democratic process33 in which participants share their perspectives and solutions regarding a problem before ranking each intervention; the process encourages discussion. Because there has been limited research on involvement of community practitioners and target populations in selecting HIV risk reduction EBIs, use of nominal consensus groups is useful to the decision-making process.31,34

Present study

The importance of practitioner and consumer involvement in the selection of an EBI has been highlighted in previous research on shared decision-making.28,35 Despite their value, these methods have not been widely adopted.36 No publications were found that had undertaken adaptation of an HIV risk reduction intervention for homeless women. Although one study discussed program consumers as important stakeholders who can help evaluate the feasibility, utility, and effectiveness of interventions and increase acceptability and motivation to participate in trials,37 very little is known about the utility of including consumers in the implementation process. Because homeless women are particularly vulnerable to engaging in risky sexual behavior, including their voices in the selection and adaptation of an HIV risk reduction EBI places value on the knowledge and lived experiences of these women and empowers them to make changes to programs and services that affect them. Including providers acknowledges their expertise in the domain of homeless services and empowers them to lead, instead of simply implementing, changes offered by others. This study highlights the process of engaging community providers, consumers, and experts to select an evidence-based HIV risk reduction intervention for adaptation that meets the needs of homeless women. There are few published real-world examples of how to use the CDC MAP18 and ADAPT-ITT19 frameworks to adapt an EBI for a highly vulnerable population (e.g., homeless women); this work serves as an important illustration of the process for other researchers and practitioners.

Methods

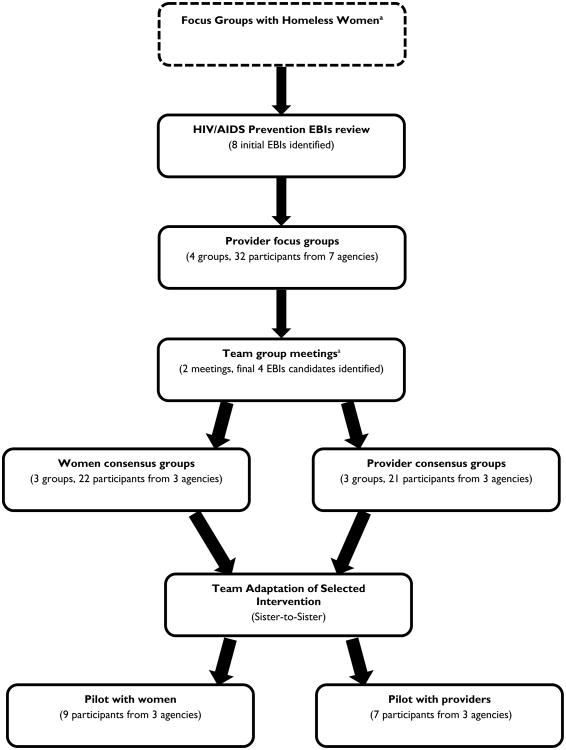

Prior to this study, the study team assessed risk and preferences among homeless women in shelter settings, a critical first step in the adaptation process.3,5,18,38 Findings from focus groups (conducted in 2009 and 2010) with homeless women highlighted that similar to other high-risk women, these women noted issues of substance use and partner type as contributing to condom use; unique findings included expressions of hopelessness and the ways in which it contributed to not using condoms.39 The current study expanded on this work, conducting focus groups with service providers and nominal consensus groups with providers and homeless women to select a DEBI intervention for adaptation. Five stages of data collection occurred, including community partners in the assessment, selection, and pretest stages18 (see Figure 1). Each stage served as the foundation for the subsequent stage. Provider focus groups built on prior group sessions with homeless women and added valuable information related to agency-related desires and constraints. Participants provided consent and completed a short survey to gather agency-level data and personal demographics prior to group sessions. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Southern California and the RAND Corporation.

Fig. 1.

Selection procedures.

aFocus groups were completed as part of a previously funded project and are published elsewhere. bPrior to meetings, an updated HIV/AIDS prevention EBI review (9 EBIs identified) was conducted based on preliminary feedback from provider focus groups and expert interviews.

Settings and sample

Recruitment areas were the downtown, Westside, and northeast areas of Los Angeles. We selected these geographically distinct regions because of the density of homeless women's services and our intention to enhance the applicability of the adapted EBI to a broad population of homeless women. We adopted a purposive sampling strategy to recruit shelter providers and women. Participants in the provider focus and consensus groups were employees affiliated with homeless service organizations who had knowledge of services needed by and available to homeless women, were aware of agency resource capacity, and had direct contact with homeless women. Recruitment flyers were placed in agencies to encourage providers to contact the study coordinator. Providers who participated in the focus groups were also invited to participate in nominal consensus groups and the pretest phase; however, prior participation was not a requirement for later participation. Participants in the consumer consensus groups were homeless women who (a) were at least 18 years old, (b) had engaged in vaginal or anal intercourse during the past six months, and (c) spoke and understood English. Recruitment of these clients occurred through notification by service providers and invitation announcements posted at facilities.

Phase 1: Review of HIV prevention EBIs

One research team member was responsible for reviewing HIV prevention EBIs maintained by DEBI and developing a list with the qualities of each intervention. We considered interventions if they were designed for women reporting heterosexual sexual activity. Nine initial EBIs that matched these criteria were selected, with length of the interventions ranging from one to nine sessions (total programming time of 200–1,080 minutes). Information gathered included targeted behaviors, core elements, activities and procedures (e.g., role-playing), resources needed for implementation (e.g., staffing), program length, and number of sessions. This information informed the protocol for provider focus groups and facilitated discussions.

Phase 2: Provider focus groups

Between April and August 2012, we conducted four provider focus groups about the perceived need for an HIV EBI in each service area, current HIV intervention resources, perceived critical elements of an ideal intervention, and potential barriers and facilitators of intervention implementation. We held two focus groups in the downtown area (one included representatives from multiple agencies) and one in each of the two other regions (see provider demographics in Table 1). All focus groups lasted about 90 minutes; participants received $30 each. Two research team members (principal investigator and coinvestigator) facilitated all groups, which were audio recorded for later transcription.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of providers.

| Variable | Focus groups n (%) |

Consensus groups n (%) |

Adaptation interviews n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 32 (100) | 21 (100) | 6 (100) |

| Gender (female) | 23 (71.9) | 14 (66.6) | 6 (100) |

| Education | |||

| High school | 8 (25.0) | 5 (25.0) | 2 (33.3) |

| Trade or technical degree | 3 (9.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (16.7) |

| Associate's degree | 3 (9.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (16.7) |

| College | 11 (34.4) | 11 (55.0) | 2 (33.3) |

| Graduate school | 6 (18.8) | 4 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Position | |||

| Case manager or intake staff | 10 (31.3) | 9 (47.3) | 4 (66.7) |

| Therapist | 5 (15.6) | 3 (15.8) | 2 (33.3) |

| Director | 2 (6.3) | 1 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 13 (40.6) | 6 (31.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Years in social servicesa | 5.50 (6.29) | 6.67 (5.82) | 8.67 (6.02) |

| Years working with homeless womena | 6.01 (6.55) | 3.75 (3.30) | 5.43 (3.08) |

Figures represent M (SD).

Phase 3: selection of EBIs for use in consensus groups

After focus group data were analyzed, the research team held two meetings in July and August 2012 to narrow down the EBI list to four candidates. All six research team members attended both 90-minute meetings. Notes were taken during both meetings to document the decision-making process. Informed by findings from the focus groups, as well as an updated EBI review, the team decided which EBIs should be kept, dropped, or tabled pending further information based on feasibility for shelter providers, intervention length, and potential costs. During the second meeting, tabled EBIs were discussed and either included or excluded based on the same criteria used during the first meeting. Using an iterative process, four EBIs were selected for discussion by consensus groups.

Phase 4: Consensus groups

Consensus methods are designed to facilitate decision-making among experts and stakeholders on challenging topics, including issues related to health care.40-43 The goal was to generate feedback on each of the selected EBIs, including a conclusive ranked list of EBI preference. In this study, we used a modified nominal group technique to conduct six consensus groups—three with providers and three with homeless women. The consumer groups occurred first, allowing feedback and opinions to be shared and discussed during provider groups. Although the provider group and consumer group scripts were quite similar, the former included a stronger focus on the fit of the EBIs with organizational capacity and constraints. Consensus groups with consumers and providers (one each in each target region) were conducted during September and October 2012. All groups were held at the facility where participants were recruited. After providing verbal consent for participation, each participant completed a short self-administered survey prior to the start of the group. Each session lasted approximately 120 minutes and was facilitated by either the principal or coinvestigator.

Nominal consensus groups began with the facilitator describing the four EBIs (see Table 2 for EBIs). The sequence in which we presented EBIs varied across groups to reduce primacy or recency bias. We orally presented information about each EBI (also provided in written form), including behaviors to be affected, core elements, activities and procedures, and number of sessions, to participants for discussion. During the provider groups, we also presented feedback from consumer consensus groups. After the presentation and discussion of all EBI candidates, each person ranked the four EBIs in order of preference on a piece of paper. Votes were tallied and the top-ranked EBI was discussed further with a focus on how best to adapt the intervention. If a clear preference did not emerge after the first vote, more discussion of the top-ranked EBIs occurred and another vote was conducted. This process continued until there was consensus or near-consensus regarding the top-ranked EBI. The facilitated EBI discussion was audio recorded for later transcription. A note-taker documented the perceived positive and negative traits of each EBI on a board visible to all participants. Both clients and providers received $30 each for their participation.

Table 2. Justification for selection of final HIV/AIDS prevention EBI candidates.

| EBIa | Strengths |

|---|---|

| CLEAR | Easily integrated with existing routine activities in real settings Addresses larger context of HIV prevention beyond sexual risk Can be delivered in shorter sessions with modification |

| RESPECT | Short (two brief sessions) Includes HIV testing and counseling Flexible in terms of adapting to other at-risk populations |

| SHIELD | Incorporates peer-education element Includes both HIV and substance use prevention elements |

| Sister-to-Sister | Delivered in group or one-on-one settings Short (one session). Knowledge and skill focused including both condom use demonstrations and partner negotiation videos and role plays. |

EBI = evidence-based intervention.

Phase 5: Procedures of EBI adaptation

Based on the outcome of the consensus groups and building off the preferences of homeless service providers and homeless women, the principal investigator and coprincipal investigator undertook the first adaptation of the top-ranked intervention. Documentation of all changes, including modifications and the rationale for all changes, occurred throughout the process. The adaptation was reviewed by all study team members and feedback based on data from focus and consensus groups was documented. This adaptation and revision process occurred two more times. When a final draft was complete, interviews were conducted with homeless women and service providers for feedback. Fifteen individuals (six providers and nine homeless women; see Table 3) engaged in dyadic interviews (two individuals in each session; one session included a third participant). Interviews took place at organizations in northeast Los Angeles (two homeless women, two service providers), downtown (five homeless women, four service providers), and the Westside (two homeless women, two service providers). After consent was provided, two facilitators introduced the modified intervention manual (including content and videos) to participants, who provided feedback on each section, including relevance and utility to homeless women. Interviews lasted 1.5 hours and were audio recoded. A note-taker also attended each session. Participants received $30 each for their participation (one volunteer participant was not paid for participation).

Table 3. Demographic characteristics of homeless women.

| Variable | Consensus groups n (%) |

Adaptation interviews n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| N | 24 (100.0) | 9 (100.0) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Black | 11 (47.8) | 3 (33.3) |

| Hispanic | 1 (4.2) | 1 (11.1) |

| Native American | 1 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| White | 7 (29.2) | 2 (22.3) |

| Other/mixed | 3 (12.5) | 3 (33.3) |

| No answer | 1 (4.2) | |

| Condom use during sex during previous 6 months | 13 (54.2) | 3 (33.3) |

| Participation in HIV prevention intervention | 6 (25.2) | 5 (55.6) |

Analysis

All audio recordings were professionally transcribed verbatim. We triangulated notes with audio recordings to create a robust record of group discussions and assist with understanding any inaudible portions of the recordings. Three members of the research team (one coinvestigator and two doctoral students who served as note-takers during groups) completed deductive analysis44 of the focus group data using the qualitative software program Atlas.ti 7.0.45 First, a codebook was created based on the semistructured interview guide. All three individuals then coded the data to identify common themes. Codes with particular value to the implementation and adaptation of the EBI were also generated. Only concepts raised during two or more provider focus groups were considered themes. We did not analyze consensus group data for thematic content but instead used them to triangulate with notes taken during the groups. These included the process of EBI selection, criteria for EBI selection, content deemed relevant to homeless women, and vote counts. Notes taken during the pretesting phased have assisted in the final adaptation currently in process.

Results

Results presented here include a discussion of the four provider focus groups, the selection of four EBIs, a description of the consensus group process, and a discussion of the adaptation and pretesting of the selected EBI. The results highlight both the content and process of adapting an EBI for homeless women.

Provider focus groups

Thirty-two individuals participated in four provider focus groups in downtown Los Angeles (n = 17 across two groups), the Westside (n = 6), and northwest Los Angeles (n = 9). Participants included staff members at various organizational levels; 47% were direct service providers. Demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. Participants shared insights related to perceived needs, critical elements of interventions, and implementation barriers and facilitators.

Perceived needs

Across groups, most providers agreed that HIV risk reduction was a high priority due to risks associated with homelessness. One individual stated, “They live dangerously because they don't have the fear factor that we have when we get to a certain age. And so they are promiscuous and they do what they do.” Another participant commented, “It's so devastating because they are not on drugs or any of the other ailments, but just from the fact that [they] need the basic necessities I've seen some of these young girls turn to selling their bodies, right?” Participants noted a lack of accessible HIV interventions for homeless women; most providers referred consumers to outside agencies for services. Providers believed women prioritized basic needs, such as housing, food, or other urgent necessities for street survival, more highly than education and skills training. One provider said, “We notice a lot of women have a lot of other things that they feel are higher priority, you know, ‘What kind of shelter am I going to be in tonight?’” Across groups, no providers felt homeless women received sufficient services related to HIV risk reduction. Although views differed on how programs might be implemented (generally regarding agency constraints), participants agreed that adapting an EBI to reduce the risk of HIV among homeless women was needed.

Critical elements of prevention programs

Most providers suggested a focus on HIV consequences and related risky behaviors, noting that most women had basic transmission knowledge but lacked perspective on how their behaviors increased their HIV risk. One provider noted:

Sometimes we have to come down where they can understand better where the rubber meets the road to say, you know what, let's show you the truth. Let me show you what it really looks like and what you really need to learn.

Participants asserted that privacy was a significant concern for these women and should be a priority in program development. As noted by one provider, “I think one-on-one is more appealing because for a lot of women, confidentiality and trusting people is really hard, so I don't know, I think one-on-one works.” They also suggested using peer educators with shared life experiences as facilitators or cofacilitators.

Intervention barriers and facilitators

Because most agencies did not have an on-site HIV prevention program, providers highlighted staff training as important to sustaining the intervention. However, they noted physical space and financial limitations at both staff and organizational levels as potential barriers. Participants concluded that a brief intervention would not only help address organizational resource barriers, but also work best because most women reside in homelessness shelters for less than three months. Providing incentives for participation, ensuring that the intervention had an “empowerment perspective,” and bundling the HIV prevention with larger programs (e.g., women's health) were also suggested. One participant recommended “keeping it simple and making it sort of fun and interesting, like, you know, and definitely incentives and, like, fun giveaways.” Some individuals felt that because of continued HIV stigma, a program marketed as HIV-only might deter attendance and interfere with retention.

Intervention delivery

There was no consensus on how the intervention should be delivered (i.e., group vs. one-on-one sessions). This may have been due to differences in characteristics of clients served and organizational resources and culture. Some providers suggested that delivering the intervention in a group could reduce staffing burden and provide an opportunity for women to discuss HIV prevention. However, others said their consumers might not be willing to disclose intimate information in a group setting. For example, “It's a privacy thing, it's personal. And I don't think you would be effective if you do it in a group.” Some felt that conducting one-on-one interventions at teachable moments might be more effective. However, other providers thought that peers might make good facilitators. One participant said, “I think a testimony would be a good one, someone who is willing to share their story where others can relate to it.”

Selection of EBIs

We began the selection process with nine identified EBIs. During the first meeting, four interventions were dropped: PROMISE,34 Future is Ours,46 Real AIDS Prevention Project,47 and VOICES.48 Reasons for these exclusions included being too general or having elements that were difficult to adapt,34 being too long,46 being too difficult to sustain and including male partners,47 and issues regarding reliability of intervention materials and depth of skill acquisition.48 Two interventions were retained: RESPECT49 and Sister-to-Sister (STS).50 We tabled decisions regarding the remaining three interventions—CLEAR,51 SISTA,52 and SHIELD53—because we felt more information was needed. During the second study team meeting SISTA52 was eliminated because of session length and cultural specificity; SHIELD53 and CLEAR51 were retained. The final four interventions selected for presentation to homeless women and providers during nominal consensus groups were CLEAR,51 RESPECT,49 SHIELD,53 and STS.50 CLEAR51 is a one-on-one evidence-based intervention which uses cognitive behavioral techniques for primary and secondary prevention. The intervention targets both males and females ages 16 and older who are either living with HIV/AIDS or individuals who are currently HIV-negative but are at high risk for HIV infection. RESPECT49 is also a one-on-one intervention that consists of two brief interactive counseling sessions; the intervention target population is women at increased risk for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. SHIELD53 is a group-level intervention for men or women who are or former ‘hard’ drug users. The implementation is of SHIELD is through trained peer educators to increase reach and accessibility this hard to reach population. Lastly, STS50 is a brief (30 minutes) one-on-one intervention that is focused on promoting safer sex skills to women at risk for HIV infection. Table 2 provides a rationale for the selection of EBIs for consideration during consensus group meetings.

Client consensus groups

Twenty-four homeless women participated in three consensus group (eight in group one, seven in group two, seven in group three, and two in group four; see demographic characteristics in Table 3). The first group participated in two rounds of ranking and discussion. During the first round, CLEAR and STS were selected most often (votes: CLEAR = 4, STS = 3, RESPECT = 1, SHIELD = 0). After discussion, a second ranking resulted in most participants selecting CLEAR as their top choice (CLEAR = 6, STS = 2). Respondents noted the most significant positive aspect of CLEAR was its inclusion of contextual factors. However, women said the adapted intervention should include the skills and communication training and role-playing found in STS. The second group unanimously selected SHIELD during the first ranking. We believe this group's clear preference for SHIELD, a unique outcome, was due to this agency's strong emphasis on substance use recovery, a primary focus of the intervention. Because the selection was unanimous, no second ranking process occurred. One disadvantage of SHIELD noted by this group was its length, making it problematic for a transitional setting. The third group was split between CLEAR and STS upon first ranking (CLEAR = 4, STS = 3; no votes for RESPECT or SHIELD). Discussion included concern from some participants that STS focused solely on HIV and that the length of this intervention was too short. A second ranking did not occur because, as a group, the women decided to prioritize CLEAR. For the fourth census group, four women were confirmed to attend; only two were able to follow through. While a less traditional group size, we ran this session as we did the others. The women were active participants who both selected STS as their top choice of intervention. A traditional “vote” was not taken at this meeting because of the women's affinity for STS. Results from the consensus groups indicated that the women were fairly split between the CLEAR and the STS interventions, highlighting strengths and concerns related to both. Women liked that CLEAR included contextual factors but thought that it needed the infusion of the skill building, role-playing, and partner negotiation elements found in STS. They emphasized a need for a skills-based intervention that was sensitive to the contexts of homeless women's lives.

Provider consensus groups

Twenty-one individuals participated in the provider consensus groups (eight in group one, five in group two, and eight in group three; see demographics in Table 1). The first ranking by the provider group was split between CLEAR and STS (3 votes each; SHIELD = 1, RESPECT = 0). Comments after the first ranking included concerns that CLEAR might not work for homeless shelters, but that STS needed to be lengthened and should include foundational topics (e.g., why women engage in risk behaviors). The second provider group also prioritized CLEAR and STS on first ranking (CLEAR = 2, STS = 3; no votes for RESPECT or SHIELD). Participants discussed incorporating elements of CLEAR into STS. For groups that did not conduct a second vote, facilitators discussed the elements of the top two choices and asked participants why they had chosen each intervention. The group discussed how these two interventions might be integrated—for example, which intervention might serve as the foundation and what elements from the second might be used to supplement. Finally, facilitators asked if participants agreed to using STS as a framework and supplementing content with elements from CLEAR, including a discussion of the specific elements to be integrated; both groups did. The last group's first ranking was varied (CLEAR = 1, STS = 3, RESPECT = 2, SHIELD = 2). Participants discussed how to prolong STS and include safe drug use. Results from the second ranking showed clear support for STS (STS = 6, CLEAR = 0, RESPECT = 1, SHIELD = 1).

In general, the provider consensus groups indicated a preference for STS, whereas those with homeless women indicated an interest in an adapted model that included elements of both CLEAR and STS. Overall, providers felt that STS was the most feasible EBI to deliver; although the intervention was not ranked highest by homeless women, they liked the skills-building elements, the female-focused empowerment lens, and the personal nature of the engagement. Concerns about its length (too short) and HIV-only focus were discussed during the consensus groups. This discussion in the women's group was mirrored within the provider groups. Facilitators noted these comments and discussed ways in which, for instance, including specific content from the CLEAR intervention as one way to adapt STS to best meet the needs of homeless women; this perspective then guided the adaptation of the STS intervention.

Adaptation interviews

Participants were allowed to freely provide feedback on the manual. Upon review of audio recordings, a chart was created to document and aggregate feedback. Comments were related to content, flow, and value of time spent in each section. Although core elements of the interventions were preserved, changes allowed for a curriculum that meets the unique needs of homeless women. A review by the study team was completed; two doctoral students on the team revisited the final manual draft to ensure all feedback had been integrated appropriately. The study team completed a final review during an in-person meeting to make decisions about which changes to accept. Pilot-testing of the finalized curriculum began in February of 2014 and will continue through Spring 2014.

Discussion

Effective adaptation of interventions is critical for the success of interventions in community-based settings. We adapted an intervention using the CDC MAP18 and ADAPT-ITT19 frameworks and described the process of implementation. There are few published studies that have provided readers with a description of real-world implementation of these frameworks to adapt an EBI for a very marginalized population; the information provided here can be used by any practitioner or organization undertaking a similar process. Use of existing evidence-based interventions allows for the improvement of HIV prevention efforts in the field54,55 and provides the community with a likely cost-effective approach to diffusing HIV risk reduction interventions to vulnerable and often marginalized populations such as homeless women. Although interventions with strong evidence exist and are made available to community providers through the CDC DEBI program, translation of EBIs into community practice has been limited due to site resource constraints, poor fit with target population needs, and mismatches between researcher and site preferences.54-56

Identification of interventions for diffusion is often solely led by researchers, which can decrease the likelihood of sustained diffusion once the project funding is removed. To address gaps in the selection of HIV risk reduction interventions, we included homeless service providers and homeless women in the needs assessment, selection process, and pretesting adaptation process. Providers were able to share their expertise with researchers, describing the provision of services to homeless women and sharing the experiences of the women they serve (as well as noting perceived needs of homeless women). We also engaged homeless women in the process of selecting an intervention that would directly affect them. These women were also treated as experts and helped drive the decision-making process. Although not a traditional community-based participatory research approach, this strategy of engaging stakeholders in the decision-making process showed respect for the unique knowledge and expertise of participants.

Evidence-based interventions must be adapted for use with differing populations and settings to maximize their effectiveness.16,18,54 This is one of few studies that involved engaging stakeholders (providers of services to homeless women, HIV experts, and homeless women) in the process of identifying the unique challenges faced by homeless women and using this information to guide the mutual selection and adaptation of an EBI to reduce HIV risk among homeless women. Our findings provide new evidence of the importance of field-based EBI translation. Conclusions about the four EBIs selected for presentation were driven by data from focus groups; the selection of the final EBI was a provider- and consumer-informed process instead of being led by researchers. Although adaptation was led by researchers, homeless women and service provides were engaged again as experts in the testing and revision of the final adapted intervention.

Lessons learned

The greatest benefit of this approach was the engagement of homeless women in shared decision-making related to interventions in which they will have the opportunity to engage. Homeless women are experts on how women experience homelessness; when empowered as part of the process their input can help increase the likelihood that the adapted EBI will meet their needs (thus increasing participation in and satisfaction with intervention-related services). This is an important lesson not only for researchers who are developing and evaluating these interventions, but for practitioners who are deciding which programs and services best meet the needs of their consumers. Obtaining feedback from prospective consumers on these programs and services prior to implementation would require minimal provider time and effort and could yield gains in terms of both actual and perceived relevance of the programs to consumers. Enhanced relevance to the women in turn may translate into increased participation rates and effectiveness for the population, thus justifying provider investment in the program and enabling all to experience the gratification of improved health and risk reduction. Indeed, in the present study, the providers' unwavering commitment and dedication to serving this population has been abundantly evident in their collaboration and has been a key ingredient in the success of this research initiative.

One of the biggest obstacles to diffusion of interventions is structural barriers within agencies and thus the involvement of providers in the process is critical. When providers are engaged in identifying these issues prior to selection, the likelihood of choosing an EBI that is most feasible for the organization (and thus increasing the likelihood of sustainability) is improved. Further, when providers are part of the selection process, they are engaged in deciding what they most want to learn (increasing their skills and ability) and what best fits a modified practice routine, because the sustainability of the program is dependent on providers making the intervention part of routine services. Including both consumers and providers in the process appeared to have the indirect effect of empowerment. Including disenfranchised individuals in the decision-making process acknowledges the value of their lived experiences and elevates them to the role of expert. When individuals are respected they become invested in the process, and this in turn facilitates the implementation and diffusion process. A secondary positive outcome was enhanced collaborative relationships between the research team and the participating organizations, which were forged through the meeting of mutually agreed-upon goals. Organizational needs were acknowledged and respected and organization members were drivers of the process.

Although we believe the inclusion of providers and consumers in the process of selecting an EBI to reduce HIV among homeless women will contribute to the diffusion of such interventions, the process is time consuming. Coordination of focus groups in busy organizations was a challenge. Incentives were helpful, as was the provision of lunch for those groups held during the midday break period. This should be considered by others planning to collaboratively select an EBI for adaptation. Accounting for the differing needs and missions of each organization and other differences (i.e., length of shelter stay) is also a challenge in the selection process. We believe this element is what drove the selection of a one-dose intervention (single session) for adaptation rather than a multimodule intervention approach. This further emphasizes the need to engage with providers and consumers to generate a culturally relevant HIV risk reduction intervention for homeless women that meets various organizational constraints including time and resources needed. This investment translates to the adaptation of a program that increases the intervention's perceived utility to the population and maps on well to the organizational environment, mission, and goals.

Limitations

We engaged with providers and homeless women who were affiliated with service organizations that agreed to allow outreach and participation. Although the individuals represented some of the largest agencies serving homeless women, they were not representative of all providers who serve homeless women in the county. Further, although 21 agency representatives and 22 homeless women participated in the consensus group process, others may have prioritized the selection of alternative HIV risk reduction EBIs. However, we believe that the consensus group process greatly increased the likelihood that the selection of STS for adaptation to meet the HIV risk reduction needs of homeless women was a thorough process that allowed all opinions to be heard.

Our objective was to develop a collaborative approach to selecting an EBI for HIV sexual risk prevention among homeless women that holds the promise of successful translation into ongoing practice in the Los Angeles homeless community. To reduce HIV incidence, it is necessary to implement and sustain EBIs in communities that serve highly vulnerable populations, yet translation of EBIs to these communities has been minimal.56,57 Evidence-based interventions must address HIV sexual risk behaviors among homeless women, but community-based providers face barriers to translating EBIs into routine practice due to poor fit with new settings and populations. Although efforts to include community stakeholders are time consuming, the costs are outweighed by the value of ownership developed throughout the process and the increased potential for sustained diffusion.

Acknowledgments

We thank the homeless women and service providers who participated in the selection processes.

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R21-DA031610-01A1; PI Wenzel).

Contributor Information

Julie A. Cederbaum, University of Southern California School of Social Work, 669 W.34th Street, Los Angeles, California, USA.

Ahyoung Song, Email: ahyoungs@usc.edu, University of Southern California School of Social Work, 669 W.34th Street, Los Angeles, California, USA.

Hsun-Ta Hsu, Email: hsuntahs@usc.edu, University of Southern California School of Social Work, 669 W.34th Street, Los Angeles, California, USA.

Joan S. Tucker, Email: jtucker@rand.org, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, California, USA.

Suzanne L. Wenzel, Email: swenzel@usc.edu, University of Southern California School of Social Work, 669 W.34th Street, Los Angeles, California, USA.

References

- 1.Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority. 2009 Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count Report. Los Angeles, CA: Author; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wenzel SL, Tucker JS, Elliott MN, et al. Sexual risk among impoverished women: understanding the role of housing status. AIDS Behav. 2007 Nov;11(6 Suppl):9–20. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9193-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryan GW, Stern SA, Hilton L, et al. When, where, why and with whom homeless women engage in risky sexual behaviors: a framework for understanding complex and varied decision-making processes. Sex Roles. 2009 Oct;61(7-8):536–53. doi: 10.1007/s11199-009-9610-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.German D, Latkin CA. Social stability and HIV risk behavior: evaluating the role of accumulated vulnerability. AIDS Behav. 2012 Jan;16(1):168–78. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9882-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kennedy DP, Wenzel SL, Tucker JS, et al. Unprotected sex of homeless women living in Los Angeles County: an investigation of the multiple levels of risk. AIDS Behav. 2010 Aug;14(4):960–73. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9621-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nyamathi A, Flaskerud JH, Leake B, et al. Evaluating the impact of peer, nurse case-managed, and standard HIV risk-reduction programs on psychosocial and health-promoting behavioral outcomes among homeless women. Res Nurs Health. 2001 Oct;24(5):410–22. doi: 10.1002/nur.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jenness SM, Kobrak P, Wendel T, et al. Patterns of exchange sex and HIV infection in high-risk heterosexual men and women. J Urban Health. 2011 Apr;88(2):329–41. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9534-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vogenthaler NS, Kushel MB, Hadley C, et al. Food insecurity and risky sexual behaviors among homeless and marginally housed HIV-infected individuals in San Francisco. AIDS Behav. 2013 Jun;17(5):1688–93. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0355-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fuller TR, Brown M, King W, et al. The SISTA pilot project: understanding the training and technical assistance needs of community-based organizations implementing HIV prevention interventions for African American women—implications for a capacity building strategy. Women Health. 2007;46(2-3):167–86. doi: 10.1300/J013v46n02_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamdallah M, Vargo S, Herrera J. The VOICES/VOCES success story: effective strategies for training, technical assistance and community-based organization implementation. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006 Aug;18(4 Suppl A):171–83. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harshbarger C, Simmons G, Coelho H, et al. An empirical assessment of implementation, adaptation, and tailoring: the evaluation of CDC's national diffusion of VOICES/VOCES. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006 Aug;18(4 Suppl A):184–97. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Somerville GG, Diaz S, Davis S, et al. Adapting the Popular Opinion Leader intervention for Latino young migrant men who have sex with men. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006 Aug;18(4 Suppl A):137–48. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Enhancing adoption of evidence-based HIV interventions: promotion of a suite of HIV prevention interventions for African American women. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006 Aug;18(4 Suppl A):161–70. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fogarty LA, Heilig CM, Armstrong K, et al. Long-term effectiveness of a peer-based intervention to promote condom and contraceptive use among HIV-positive and at-risk women. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(Suppl 1):103–19. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.S1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jemmott JB, 3rd, Jemmott LS, Fong GT, et al. Effectiveness of an HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention for adolescents when implemented by community-based organizations: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health. 2010 Apr;100(4):720–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.140657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller RL, Shinn M. Learning from communities: overcoming difficulties in dissemination of prevention and promotion efforts. Am J Community Psychol. 2005 Jun;35(3-4):169–83. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-3395-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eke AN, Neumann MS, Wilkes AL, et al. Preparing effective behavioral interventions to be used by prevention providers: The role of researchers during HIV prevention research trials. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006 Aug;18(4 Suppl A):44–58. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKleroy VS, Galbraith JS, Cummings B, et al. Adapting evidence-based behavioral interventions for new settings and target populations. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006 Aug;18(4 Suppl A):59–74. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. The ADAPT-ITT model: a novel method of adapting evidence-based HIV interventions. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008 Mar;47(Suppl 1):S40–6. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181605df1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clancy CM, Cronin K. Evidence-based decision-making: global evidence, local decisions. Health Aff. 2005 Jan-Feb;24(1):151–62. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelly JA, Somlai AM, DiFranceisco WJ, et al. Bridging the gap between the science and service of HIV prevention: transferring effective research-based HIV prevention interventions to community AIDS service providers. Am J Public Health. 2000 Jul;90(7):1082–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.7.1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lyles CM, Crepez N, Herbst JH, et al. Evidence-based HIV behavioral prevention from the perspective of the CDC's HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis Team. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006 Aug;18(4 Suppl A):21–31. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wandersman A, Duffy J, Flaspohler P, et al. Bridging the gap between prevention research and practice: the Interactive Systems Framework for Dissemination and Implementation. Am J Community Psychol. 2008 Jun;41(3-4):171–81. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9174-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prather C, Fuller TR, King W, et al. Diffusing an HIV prevention intervention for African American women: integrating Afrocentric components into the SISTA diffusion strategy. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006 Aug;18(4 Suppl A):149–60. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Collins C, Harshbarger C, Sawyer R, et al. The Diffusion of Effective Behavioral Interventions project: development, implementation, and lessons learned. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006 Aug;18(4 Suppl A):5–20. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schensul JJ. Organizing community research partnerships in the struggle against AIDS. Health Educ Behav. 1999 Apr;26(2):266–83. doi: 10.1177/109019819902600209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gandelman AA, DeSantis LM, Rietmeijer CA. Assessing community needs and agency capacity: an integral part of implementing effective evidence-based interventions. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006 Aug;18(4 Suppl A):32–43. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango) Soc Science Med. 1997 Mar;44(5):681–92. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00221-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loh A, Simon D, Wills CE, et al. The effects of a shared decision-making intervention in primary care of depression: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2007 Aug;67(3):324–32. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Castro FG, Barrera M, Jr, Holleran Steiker LK. Issues and challenges in the design of culturally adapted evidence-based interventions. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2010;6:213–39. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-033109-132032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones J, Hunter D. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ. 1995 Aug;311(7001):376–80. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7001.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Ruyter K. Focus versus nominal group interviews: a comparative analysis. Marketing Intell Plan. 1996;14(6):44–50. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carney O, McIntosh J, Worth A. The use of the nominal group technique in research with community nurses. J Adv Nurs. 1996 May;23(5):1024–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1996.09623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.CDC AIDS Community Demonstration Projects Research Group. Community-level HIV intervention in 5 cities: final outcome data from the CDC AIDS Community Demonstration Projects. Am J Public Health. 1999 Mar;89(3):336–45. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.3.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacPhail A. Nominal group technique: a useful method for working with young people. Br Educ Res J. 2001 Apr;27(2):161–70. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Edwards A, Elwyn G. Shared decision-making in health care: achieving evidence-based patient choice. In: Edwards A, Elwyn G, editors. Shared decision-making in health care: achieving evidence-based patient choice. 2nd. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carlsen B, Aakvik A. Patient involvement in clinical decision-making: the effect of GP attitude on patient satisfaction. Health Expect. 2006 Jun;9(2):148–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2006.00385.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nastasi BK, Varjas K, Schensul SL, et al. The participatory intervention model: a framework for conceptualizing and promoting intervention acceptability. Sch Psychol Q. 2000;15(2):207–32. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tucker JS, Wenzel SL, Golinelli D, et al. Is substance use a barrier to protected sex among homeless women? results from between- and within-subjects event analyses. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010 Jan;71(1):86–94. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cederbaum JA, Wenzel SL, Gilbert ML, et al. The HIV risk reduction needs of homeless women in Los Angeles. Womens Health Issues. 2013 May-Jun;23(3):e167–72. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wenzel SL, Ebener P, Farley D. Building a client-level process and outcomes monitoring system: Phoenix House RAND research partnership. Santa Monica, CA: RAND; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fink A, Kosecoff J, Chassin M, et al. Consensus methods: characteristics and guidelines for use. Santa Monica, CA: RAND; 1999. RAND publication N-3367-HHS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Totikidis V. Applying the nominal group technique (NGT) in community based action research for health promotion and disease prevention. Aust Community Psychol. 2010;22(1):18–29. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008 Apr;62(1):107–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Friese S. ATLAS ti 7 User Manual. Berlin: ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ehrhardt AA, Exner TM, Hoffman S, et al. A gender-specific HIV/STD risk reduction intervention for women in a health care setting: short- and long-term results of a randomized clinical trial. AIDS Care. 2002 Apr;14(2):147–61. doi: 10.1080/09540120220104677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lauby JL, Smith PJ, Stark M, et al. A community-level HIV prevention intervention for inner-city women: results of the Women and Infants Demonstration Projects. Am J Public Health. 2000 Feb;90(2):216–22. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.2.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O'Donnell CR, O'Donnell L, San Doval A, et al. Reductions in STD infections subsequent to an STD clinic visit: using video-based patient education to supplement provider interactions. Sex Transm Dis. 1998 Mar;25(3):161–8. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199803000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kamb ML, Fishbein M, Douglas JM, et al. Efficacy of risk-reduction counseling to prevent human immunodeficiency virus and sexually transmitted diseases: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998 Oct;280(13):1161–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.13.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jemmott LS, Jemmott JB, 3rd, O'Leary A. Effects on sexual risk behavior and STD rate of brief HIV/STD prevention interventions for African American women in primary care settings. Am J Public Health. 2007 Jun;97(6):1034–40. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.020271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Comulada WS, Swendeman DT, Rotheram-Borus MJ, et al. Use of HAART among young people living with HIV. Am J Health Behav. 2003 Jul-Aug;27(4):389–400. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.27.4.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM. A randomized controlled trial of an HIV sexual risk–reduction intervention for young African-American women. JAMA. 1995 Oct;274(16):1271–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Latkin CA, Sherman S, Knowlton A. HIV prevention among drug users: outcome of a network-oriented peer outreach intervention. Health Psychol. 2003 Jul;22(4):332–9. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.4.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Crepaz N, Marks G, Liau A, et al. Prevalence of unprotected anal intercourse among HIV-diagnosed MSM in the United States: a meta-analysis. AIDS. 2009 Aug;23(13):1617–29. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832effae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Noar SM. Behavioral interventions to reduce HIV-related sexual risk behavior: review and synthesis of meta-analytic evidence. AIDS Behav. 2008 May;12(3):335–53. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9313-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Glasgow RE, Lichtenstein E, Marcus AC. Why don't we see more translation of health promotion research to practice? rethinking the efficacy-to-effectiveness transition. Am J Public Health. 2003 Aug;93(8):1261–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Glasgow RE, Emmons KM. How can we increase translation of research into practice? types of evidence needed. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:413–33. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]