Abstract

Objective

Fat soluble vitamin (FSV) deficiency is a well-recognized consequence of cholestatic liver disease and reduced intestinal intraluminal bile acids. We hypothesized that serum bile acids (SBA) would predict biochemical FSV deficiency better than serum total bilirubin level (TB) in infants with biliary atresia.

Methods

Infants enrolled in the Trial of Corticosteroid Therapy in Infants with Biliary Atresia (START) after hepatoportoenterostomy were the subjects of this investigation. Infants received standardized FSV supplementation and monitoring of TB, SBA and vitamin levels at 1, 3 and 6 months. A logistic regression model was used with the binary indicator variable insufficient/sufficient as the outcome variable. Linear and non-parametric correlations were made between specific vitamin measurement levels and either TB or SBA.

Results

The degree of correlation for any particular vitamin at a specific time point was higher with TB than SBA (higher for TB in 31 circumstances versus 3 circumstances for SBA). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) shows that TB performed better than SBA (AUC 0.998 vs. 0.821). Including both TB and SBA did not perform better than TB alone (AUC 0.998).

Conclusion

We found that TB was a better predictor of FSV deficiency than SBA in infants with biliary atresia. The role of SBA as a surrogate marker of FSV deficiency in other cholestatic liver diseases, such as PFIC, alpha-one antitrypsin deficiency and Alagille syndrome where the pathophysiology is dominated by intrahepatic cholestasis, warrants further study.

Keywords: fat –soluble vitamin, cholestasis, serum bile acid, biliary atresia, bilirubin

Introduction

Cholestatic liver disease results from diminished bile flow leading to decreased intestinal intraluminal bile acids and increased levels of serum bile acids and serum total bilirubin. One well recognized consequence of cholestatic liver disease and reduced intraluminal bile acids is nutritional deficiency since bile acids are essential for fat and fat soluble vitamin absorption. Intestinal bile acids must be present in excess of the critical micellar concentration for optimal absorption of fat and fat soluble vitamins and commonly fall below this level in cholestasis.

The consequences of fat soluble vitamin deficiency are well described. Recognition of deficiency states and provision of adequate oral or parenteral supplementation with close monitoring is critical to optimal management of infants and children with cholestatic liver disease such as biliary atresia.

Biliary atresia is a progressive cholangiopathy that causes fibrotic obliteration of intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts in infants and presents in the first two months of life. Recent analysis of prospectively collected data from infants with biliary atresia in the Childhood Liver Disease Research and Education Network (ChiLDREN) funded by the National Institutes of Health, characterized rates of fat soluble vitamin deficiency in patients with biliary atresia. Fat soluble vitamin deficiency was inversely correlated to serum total bilirubin and was more prevalent in infants whose serum total bilirubin was greater than 2 mg/dl. 1

Prior studies have proposed that serum bile acids may be a more precise marker of cholestasis in chronic cholestatic liver disease.2–4 We therefore hypothesized that serum bile acid (SBA) would predict biochemical fat soluble deficiency better than total bilirubin (TB) level in infants with biliary atresia. The previously reported study has now been reassessed relative to serum bile acids to test this hypothesis.

Materials and Method

Infants enrolled in the Trial of Corticosteroid Therapy in Infants with Biliary Atresia (START) conducted by the NIH funded ChiLDREN study were the subjects of this investigation. The study was a randomized double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial of corticosteroid therapy after hepatoportoenterostomy.5 Fat soluble vitamin preparation (ADEK, AquADEK), vitamin K and ursodiol were provided to the subjects of the study as part of a cooperative agreement between the manufacturer and the NIDDK. Standardized dosing after hepatoportoenterostomy was established for study participants.5 Target ranges and dosing recommendations for further supplementation with individual fat soluble vitamins was provided to the centers. (Table 1) Informed consent was obtained from the parent or guardian for all study participants and IRB approval was obtained at each local center.

Table 1.

Target Fat Soluble Vitamin Levels and Replacement Regimens

| Vitamin | Target range | Supplementation strategy |

|---|---|---|

| A(retinol) | 19 – 77 µg/dL retinol:retinol binding protein molar ratio > 0.8 |

Increments of 5000 IU(up to 25 – 50,000 IU/day) orally or monthly intramuscular administration of 50,000 IU |

| D (25-hydroxy vitamin D) |

15 – 45 ng/ml | Increments of 1200 to 8000 IU orally daily of cholecalciferol or ergocalciferol Alternatively calcitriol at 0.05 to 0.20 µg/kg/day |

| E (alpha tocopherol) |

3.8 – 20.3 µg/ml Vitamin E:total serum lipids ratio > 0.6 mg/g |

Increments of 25 IU/kg of TPGS orally daily(to 100 IU/kg/day) |

| K (phytonadione) |

INR≤1.2 | 1.2 < INR≤ 1.5 2.5 mg vitamin K orally daily 1.5 < INR≤ 1.8 2.0 – 5.0 mg vitamin K intramuscular and 2.5 mg vitamin K orally daily INR > 1.8 2.0 – 5.0 mg vitamin K intramuscular and 5.0 mg vitamin K orally daily |

Serum concentrations of fat soluble vitamins, RBP and total lipids were performed in the Clinical Translational Research Center Core Laboratory at the Children’s Hospital (Aurora, CO) as previously described.6 Pediatric reference ranges used for target vitamin levels in this study followed published criteria.7,8 Vitamin insufficiency was defined as vitamin measurements (serum level for 25 hydroxyvitamin D, retinol: retinol binding protein for vitamin A and serum alpha tocopherol:total lipid ratio for vitamin E below the lower limit of the normal range or elevated INR for vitamin K. (Table 1) Measures of vitamin sufficiency included both vitamin E and vitamin E:lipid ratio to ensure compensation for hyperlipidemia associated with cholestasis. Similarly, both retinol and retinol: RBP ratio was calculated as indices of vitamin A status to assess hepatic stores.

Total SBA was determined by enzymatic and colorometric method (Diazyme Laboratories, Poway, CA) in the Clinical Translational Research Center Core Laboratory at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Bile acids are converted to 3-oxo bile acids with 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3α-HSD) with concomitant reduction of NAD+ to NADH. Age-specific reference ranges were determined in this laboratory in 1995 – 1996. The ranges are published in Pediatric Reference Ranges, 2nd Ed., AACC Press, Washington D.C., 1997.

Blood testing for prothrombin time/INR, TB, total SBA, total lipids, retinol binding protein (RBP), retinol, alpha tocopherol and 25 hydroxyvitamin D was performed at 1, 3, and 6 months after HPE as part of the START protocol. Vitamin levels, PT/INR, TB and SBA were available 1, 3, and 6 months post-HPE on varying numbers of subjects. A separate analysis was performed for each time point. Treatment with steroids after HPE did not affect outcome by multiple measures including bilirubin at any time point up until 24 months of age, duration of bile drainage, or survival without liver transplantation. As such, subjects in this study were considered in aggregate without knowledge of whether they had received placebo or steroids with respect to all measures.5 All patients received supplementation according to the guidelines noted independent of their randomization status.

Initial analyses of a relationship between TB or SBA and vitamin levels were performed by linear regression. Given the nonlinear relationship between the vitamin levels and TB and SBA, Kendall’s tau was also computed between the vitamin level and TB or SBA and assessed for statistical significance.

To assess the value of using both TB and SBA as biomarkers to identify subjects with vitamin insufficiency, a logistic regression model was used with the binary indicator variable insufficient/sufficient as the outcome variable. Three regression models were compared: TB alone as the predictor, SBA alone as the predictor and both TB and SBA as predictors. The receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve under each model was used to evaluate TB or SBA as risk factors for insufficiency. Specifically, the area under the curve (AUC) of the two ROC curves was assessed for statistical significance. A bootstrap procedure was used to compute the standard error for the difference in the area under the curve for ROCs for any two models. Using the ROC curves for the ‘TB only’ model and the ‘SBA only’ model, the best TB and SBA cutoff values (those values that maximize the probability of correctly classifying a subject as vitamin insufficient/sufficient) were determined. All analyses were performed using SAS/STAT (SAS Institute Inc. 2008. SAS/STATR 9.2 User’s Guide. Cary NC: SAS Institute Inc.)

Results

Between September 21, 2005 and October 31, 2008, 92 infants with BA were enrolled in the study. Data were collected up to July 1, 2009. Information was available at entry, 1, 3 and 6 months after HPE in 92, 86, 83 and 61 infants, respectively. Forty-seven percent of the subjects were male, 23% Hispanic, 60% White, 16% Black, and 24% other races (Asian, Native American and unknown).

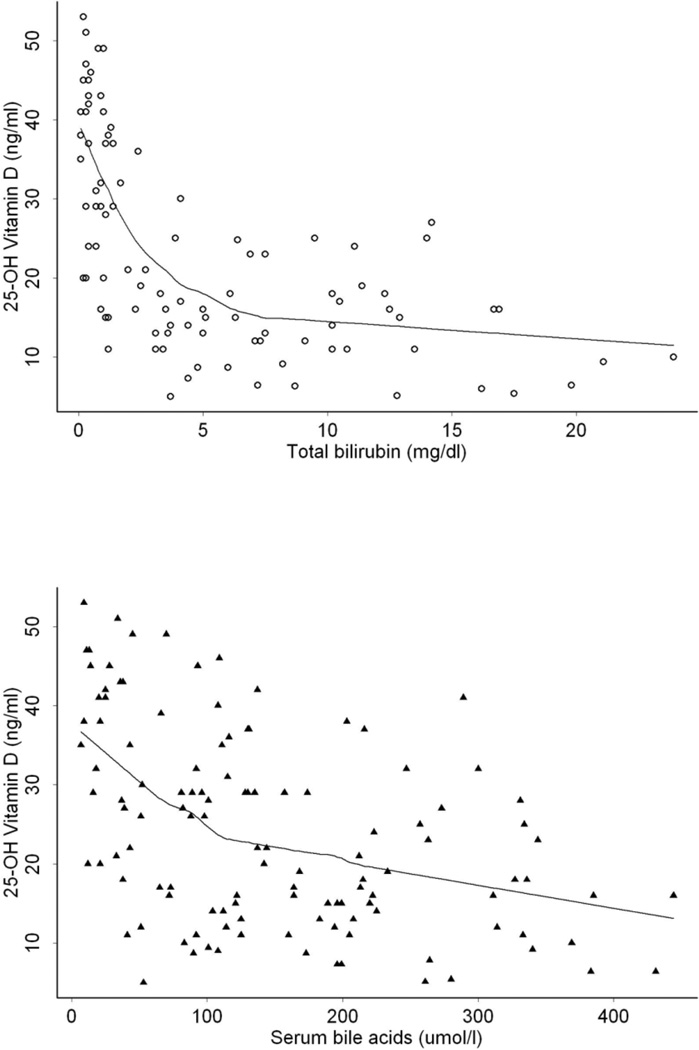

Analysis was performed to determine whether SBA or TB levels were a better predictor of vitamin deficiency at time points after HPE. Comparative scatterplots of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D plotted against SBA and TB levels with spline correlation is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Comparative scatterplots of 25-hydroxyvitamin D plotted against SBA and TB levels. Spline correlation depicted by the solid line with a more apparent inverse relationship between total bilirubin and 25-hydroxyvitamin D.

Linear (Pearson’s) and non-parametric (Kendall’s) correlations were made between specific vitamin measurement levels and either serum TB or SBA concentrations at 1, 3 and 6 months after HPE (Tables 2 and 3, respectively). Negative correlations were demonstrated between TB or SBA and vitamins A, D and E measurements, and positive correlations were demonstrated with INR. The correlation for any particular vitamin at a specific time point was higher with serum TB than SBA and equally distributed across linear (15 circumstances) and non-parametric (16 circumstances) correlations. In total, TB showed a greater degree of correlation with specific vitamin levels at 31 time points compared to 3 circumstances for SBA.

Table 2.

Linear Correlation Analysis of Vitamin Level Relative to Total Bilirubin (TB) or Serum Bile Acids (SBA)

| TB correlation (mg/dl) |

SBA correlation (μMol/L) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| correlation | P-value | correlation | P-value | |

|

Retinol (A) (µg/dl) |

||||

| 1 month | −.300 | .05 | −.372* | <.01 |

| 3 months | −.576 | <.01 | −.408 | <.01 |

| 6 months | −.625 | <.01 | −.394 | .02 |

|

Retinol/RBP (molar ratio) |

||||

| 1 month | −.321 | .05 | −.149 | .35 |

| 3 months | −.398 | .03 | −.395 | .01 |

| 6 months | −.652 | <.01 | −.278 | .15 |

|

Alpha tocopherol (E) (µg/ml) |

||||

| 1 month | −.496 | <.01 | −.227 | .12 |

| 3 months | −.349 | .03 | −.127 | .40 |

| 6 months | −.512 | <.01 | −.231 | .20 |

|

E/lipids (mg/g) |

||||

| 1 month | −.588 | <.01 | −.362 | .03 |

| 3 months | −.602 | <.01 | −.457 | <.01 |

| 6 months | −.498 | .02 | −.525 | <.01 |

|

25−hydroxyvitamin D (ng/ml) |

||||

| 1 month | −.458 | <.01 | −.326 | .03 |

| 3 months | −.600 | <.01 | −.360 | .02 |

| 6 months | −.714 | <.01 | −.680 | <.01 |

| INR (K) | ||||

| 1 month | .495 | <.01 | .135 | .39 |

| 3 months | .536 | <.01 | .318 | .06 |

| 6 months | .595 | <.01 | .200 | .30 |

Correlation in bold has p-value < 0.05 and is of greater magnitude in a comparison between TB and SBA

Table 3.

Nonparametric Correlation Analysis of Vitamin Levels Relative to Total Serum Bilirubin (TB) or Serum Bile Acids (SBA)

| TB (mg/dl) correlation | SBA (μMol/L) correlation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| correlation | P-value | Correlation | P-value | |

|

Retinol (A) (μg/dl) |

||||

| 1 month | −.236 | .03 | −.251* | .01 |

| 3 months | −.395 | <.01 | −.285 | <.01 |

| 6 months | −.585 | <.01 | −.395 | <.01 |

|

Retinol /RBP (molar ratio) |

||||

| 1 month | −.138 | .23 | .000 | 1.00 |

| 3 months | −.352 | <.01 | −.290 | <.01 |

| 6 months | −.493 | <.01 | −.289 | .03 |

|

Alpha tocopherol (E) (μg/ml) |

||||

| 1 month | −.346 | <.01 | −.168 | .09 |

| 3 months | −.329 | <.01 | −.187 | .07 |

| 6 months | −.418 | <.01 | −.143 | .24 |

|

E/lipids (mg/g) |

||||

| 1 month | −.507 | <.01 | −.257 | <.01 |

| 3 months | −.506 | <.01 | −.397 | <.01 |

| 6 months | −.496 | <.01 | −.492 | <.01 |

|

25−hydroxyvitamin D (ng/ml) |

||||

| 1 month | −.333 | <.01 | −.197 | .06 |

| 3 months | −.356 | <.01 | −.227 | .03 |

| 6 months | −.689 | <.01 | −.536 | <.01 |

| INR (K) | ||||

| 1 month | .308 | <.01 | .192 | .08 |

| 3 months | .349 | <.01 | .303 | <.01 |

| 6 months | .449 | <.01 | .055 | .68 |

Correlation in bold has p-value < 0.05 and is of greater magnitude in a comparison between TB and SBA

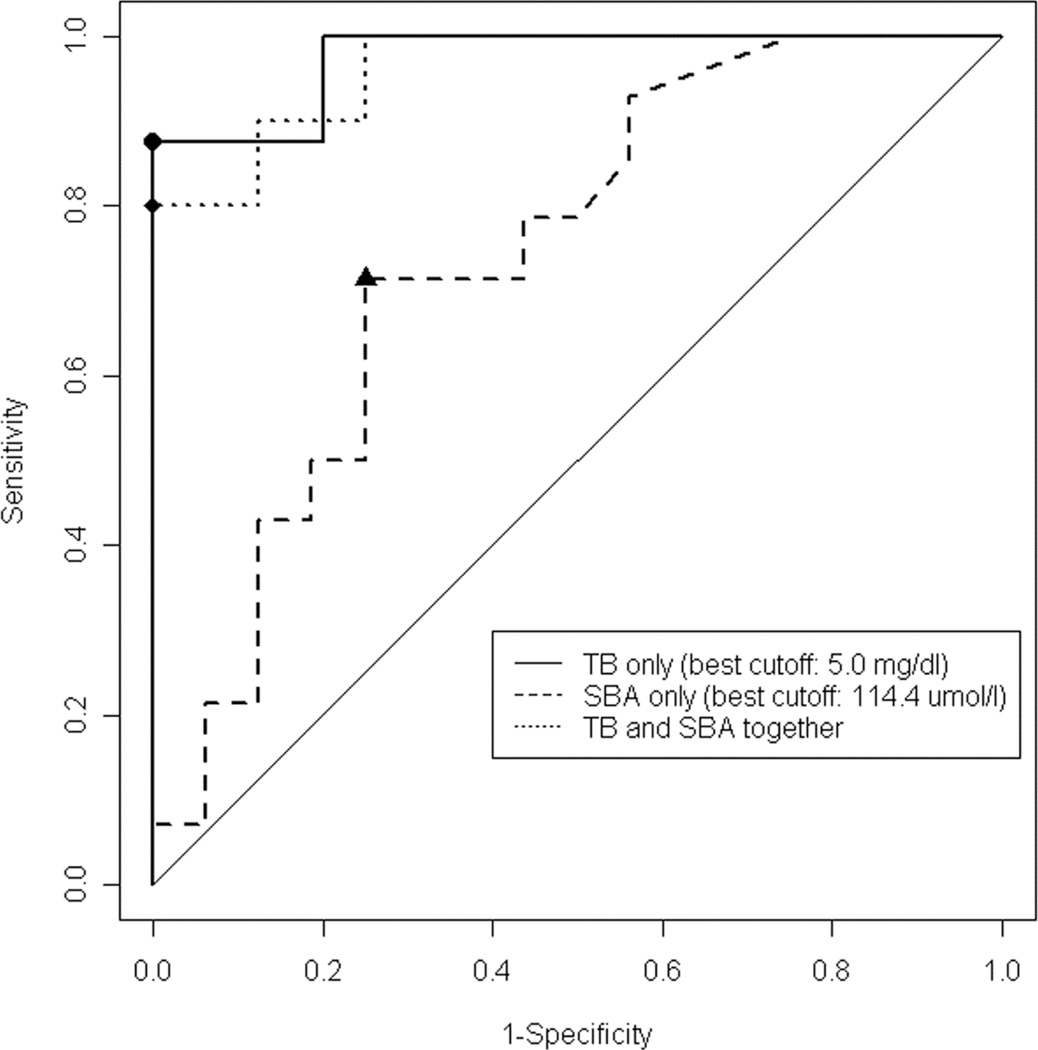

An alternative analysis utilized the ROC of the ability of either TB or SBA to predict a specific or any vitamin insufficiency. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) in the predictive model for any FSV deficiency at 6 months shows that TB performed better than SBA (AUC 0.998 vs. 0.821). Including both TB and SBA level did not perform better than total bilirubin alone (AUC 0.998). (Figure 2) In a comparison between TB and SBA for specific time points for each vitamin level, ROC AUC of TB was of greater magnitude (p<0.05) for more time points. (Table 4)

Figure 2.

Comparison between TB and SBA for specific time points for each vitamin level. The ROC AUC of TB had was of greater magnitude (p<0.05)

Table 4.

ROC Analysis of Prediction of Vitamin Deficiency By Total Serum Bilirubin (TB) or Serum Bile Acids (SBA)

| TB ROC (mg/dl) |

SBA ROC (μM) |

P-value (favored predictor bolded |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC | Cut off | AUC | Cut off | ||

|

Retinol (<20 µg/dl) |

|||||

| 1 month | .694 | 6.9 | .903* | 234 | .01 |

| 3 months | .870 | 6.5 | .765 | 169 | .01 |

| 6 months | .870 | 5.0 | .801 | 125 | .01 |

|

Retinol/RBP (Molar ratio < 0.8) |

|||||

| 1 month | .665 | 3.7 | .531 | 233 | 0.17 |

| 3 months | .767 | 1.4 | .683 | 142 | nc^ |

| 6 months | .964 | nc^ | .814 | 73 | <.01 |

|

Alpha tocopherol (E) (<3.8 µg/ml) |

|||||

| 1 month | .801 | 6.1 | .660 | 268 | .69 |

| 3 months | .929 | 13.2 | .585 | 101 | .17 |

| 6 months | .849 | 12.8 | .750 | 261 | nc^ |

|

E/lipids (<0.6 mg/g) |

|||||

| 1 month | .904 | 6.1 | .784 | 164 | .34 |

| 3 months | .904 | 10.2 | .804 | 215 | .06 |

| 6 months | .890 | 5.0 | .750 | 261 | .98 |

|

25-hydroxyvitamin D (<15 ng/ml) |

|||||

| 1 month | .643 | 3.1 | .556 | 184 | .29 |

| 3 months | .801 | 3.5 | .602 | 90 | .04 |

| 6 months | .941 | 1.2 | .856 | 172 | <.01 |

|

INR (K) (>1.2) |

|||||

| 1 month | .872 | 10.5 | .608 | 117 | .11 |

| 3 months | .820 | 3.5 | .805 | 169 | nc^ |

| 6 months | .938 | 7.5 | .792 | 114 | .18 |

| Any Deficiency | |||||

| 1 month | .856 | 3.1 | .774 | 104 | .18 |

| 3 months | .931 | 3.5 | .776 | 168 | <.01 |

| 6 months | .987 | 5.0 | .821 | 114 | <.01 |

ROC AUC in bold has p-value < 0.05 and is of greater magnitude in a comparison between TB and SBA

nc - not calculable

Optimal cut-off values for predicting vitamin insufficiency were generally in the range of 3-8 mg/dL for TB and 100 to 200 mcMol/Lfor SBA.

Discussion

Contrary to our hypothesis when we initiated this study, we found that serum total bilirubin was a better predictor of fat soluble vitamin deficiency than serum bile acids in infants with biliary atresia when sequential fat soluble vitamin levels were assessed over the three year timeframe of the study. Combining both total bilirubin and serum bile acids in the ROC analysis did not improve the results compared to total bilirubin alone.

In cholestasis, fat soluble vitamin deficiency results from impaired bile flow leading to inadequate concentrations of bile acids in the intestinal lumen. The absorption of fat soluble vitamins requires formation of micelles that solubilize them into the aqueous environment of the intestinal lumen and facilitates their passive diffusion across the enterocyte. Bile acid levels in the intestinal lumen below a critical micellar concentration lead to impaired absorption of fat and fat soluble vitamins in cholestatic liver disease.

The pathophysiology of biliary atresia relates to an inflammatory and progressive fibrotic obstruction of the extrahepatic and intrahepatic biliary tract progressing at variable rates to end stage liver disease. Since the predominant effect is extrahepatic obstruction, TB may have an inordinately weighted contribution as a biochemical manifestation of cholestasis. This occurs despite the well described physiologic role of bile acids as the principal driver of bile flow.

This contrasts with other disorders such as Alagille Syndrome, alpha-1-AT deficiency or PFIC 1, 2 or 3 in which intrahepatic cholestasis is the predominant pathophysiologic finding. Because of the unique pathophysiology of these cholestatic conditions in infancy and childhood, bilirubin might not be as robust a predictor of submicellar concentration of bile acids in the intestinal lumen and SBA might prove more effective. SBA in these conditions may be markedly elevated in the presence of normal or minimally elevated serum bilirubin. 9,10 Even in the absence of overt jaundice, patients with these disorders can present with clinical sequelae of fat soluble vitamin deficiency such as rickets, fractures and bleeding diathesis. 10,11

The results of previous studies in patients with intrahepatic cholestasis (including primary biliary cirrhosis, alpha-1-antityrpsin deficiency, Alagille Syndrome and presumed PFIC patients) have suggested that the SBA concentration might be a surrogate for intraluminal bile acid concentration and thereby could be used as a predictor of fat soluble vitamin absorption.12 A serum cholyglycine between 34-118μMol/l was associated with intraluminal bile acid concentration below 2 mMol /L (the proposed CMC) and likely associated with fat and fat soluble vitamin deficiency. Serum CG likely constitutes no more than 25-30% of the total bile acid pool with concomitant contribution to the total serum bile acid concentrations. It is therefore possible to extrapolate that a CG of 34-118 μMol/l might be equivalent to total bile acid levels measured by the enzymatic method, used in the current study, of 136-472 μMol/l thereby approximating the levels of 100-200 μMol/L as the threshold associated with vitamin malabsorption in this study.12

This relationship between SBA levels, intestinal concentrations of bile acids, and vitamin E absorption has also been described in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Biochemical markers of cholestasis including serum bilirubin and serum cholyglycine were significantly higher in patients with vitamin E deficiency. More importantly, absorption of vitamin E, as measured by analysis of serial levels after an oral loading dose, was impaired in patients with more advanced liver disease based on histologic stage as well as in patients with biochemical evidence of deficiency at baseline.13

The administration of a liquid multiple FSV preparation (ADEKs or AquADEKs© made with tocopherylpolyethylene glycol-1000 succinate (TPGS)) along with additional vitamin K was part of the routine clinical care for this study cohort. Oral tolerance testing of TPGS during the course of studying its use to treat vitamin E deficiency in children with chronic cholestatic conditions has shown improved intestinal absorption with this water soluble preparation compared to conventional formulations.13 The need to bypass physiologic enteral absorption with a water soluble compound or intramuscular/intravenous preparations to attain a state of sufficiency underscores the obligate role of bile acids in fat soluble vitamin absoprtion in patients with cholestatic liver disease. These studies in vitamin E are more accurate markers of absorption as vitamin D is synthesized endogenously and prothrombin time and INR are relatively crude measures of vitamin K deficiency. 14–16

Though the use of an available TPGS-based compound is likely to have attenuated the degree of fat soluble vitamin deficiency1 biochemical evidence of FSV insufficiency is still common in infants with biliary atresia at all time points (1, 3 and 6 months after HPE) for vitamin A (29%–36% of patients), vitamin D (21%–37%), vitamin K (10%–22%), and vitamin E (16%–18%). It is therefore not surprising that the correlation of TB are of increasingly greater magnitude over time after HPE (1, 3, 6 months), as FSV insufficiency is persistent despite treatment with ADEK and AquADEK particularly in patients with cholestasis measured by a TB of >2 ng/dl.

Fat soluble vitamin insufficiency in infants and children with cholestatic liver disease is detected by regular screening. Additionally, after FSV supplementation is prescribed, ongoing monitoring of fat soluble vitamin levels is necessary to ensure sufficiency and to evaluate for toxicity. Measurement of FSV levels in infants and children has practical limitations including blood volume and cost. A reliable biomarker such as the TB above which FSV deficiency is likely could provide a method of screening by which patients should be aggressively monitored for fat soluble vitamin deficiency. Using a cutoff of 3-4 mg/dl TB as an indicator of risk for vitamin deficiency in infants with biliary atresia might be cost effective and subject only the most at risk patients to additional phlebotomy and blood collection to monitoring and prevention of FSV insufficiency in patients with biliary atresia.

Determinants of vitamin D status include not only cholestasis and malabsorption, but also synthetic function of the liver, skin pigmentation and light exposure. Though concentrations representing vitamin D sufficiency/insufficiency are generally accepted, there is no published vitamin D screening guideline either for the general pediatric population or for children at risk. These multiple factors contributing to vitamin D sufficiency may require screening in infants and young children with biliary atresia even if the serum bilirubin is low. Vitamin D supplementation in infants and young children with biliary atresia should follow published recommendations for daily vitamin D intake. 17

There are a few limitations of this study. Though standardized vitamin supplementation and dosing was encouraged as part of the study protocol, center-specific, routine clinical care was permitted at the individual centers. The timing of collection of serum for bile acid measurement was not standardized and there is a recognized postprandial rise in serum bile acids in normal infants, children and adults.18 In cholestatic patients, the differences between fasting and postprandial SBA is likely less significant and this likely had a minimal, if any, effect, on the observed results.19 The ChiLDREN and START studies include 14 clinical sites, geographically located across the United States and should be generalizable to all infants with biliary atresia. However, because this study was specific to infants with biliary atresia, the findings may not be applicable to infants with other liver diseases in which serum bile acids may be required to diagnose cholestasis or to determine if ongoing treatment with ursodehoxycholic acid and fat soluble vitamin supplementation is needed.

The findings of the present study suggest that serum total bilirubin in infants with biliary atresia is a robust biomarker of FSV insufficiency and it is superior to serum bile acid measurement. This is a practical finding as measurement of TB is more readily available than SBA. The role of serum bile acids as a surrogate marker of FSV deficiency in other cholestatic liver diseases in children, with pathophysiologies different from biliary atresia, warrants further study.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING: This work was supported by U01 grants from the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Disease (DK62453 [Dr. Sokol], DK84538 [Dr. Wang], DK62500 [dr. Rosenthal], DK62470 [Dr. Karpen], DK62436 [Dr. Whitington], DK84536 [Dr. Molleston], DK62503 [Dr. Schwarz], DK62452 [Dr. Turmelle], DK62445 [Dr. Arnon], DK62497 [Dr. Bezerra], DK62481 [Dr. Loomes], DK62466 [Dr. Shneider], DK84575 [Dr. Murray], DK62470 [Dr. Hertel]) and CTSA grants from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR000154 [Colorado], UL1TR000130 [Los Angeles], UL1TR000004 [San Francisco], UL1TR000454 [Atlanta], UL1TR000150 [Chicago], UL1TR000006 [Indianapolis], Ul1TR000424 [Baltimore], UL1TR000448 [St.Louis], UL1TR000077 [Cincinnati], UL1TR000003 [Philadelphia], UL1TR000005 [Pittsburgh], UL1TR000423 [Seattle]. Funded by the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Trial Identification Number: NCT00294684, clinicaltrials.gov, childrennetwork.org

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: Dr Sokol is a consultant for and on the scientific advisory board of Yasoo Health, Inc, which is the distributor for AquADEKs and ADEKs. The company had no involvement in designing the research, interpreting the data, or writing the article; the other authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

References

- 1.Shneider BL, Magee JC, Bezerra JA, et al. Efficacy of fat-soluble vitamin supplementation in infants with biliary atresia. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e607–e614. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fausa O, Gjone E. Serum Bile Acid Concentrations in Patients With Liver Disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1976;11:537–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ian A, Bouchier D, Pennington R. Serum Bile Acids in Hepatobiliary Disease. Gut. 1978;19:492–496. doi: 10.1136/gut.19.6.492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skrede S, Solberg H, Blomhoff J, et al. Bile acids Measured in Serum During Fasting as a Test for Liver Disease. Clin Chem. 1978;24:1095–1099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bezerra JA, Spino C, Magee JC, et al. Use of corticosteroids after hepatoportoenterostomy for bile drainage in infants with biliary atresia: the START randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:1750–1759. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feranchak AP, Sontag MK, Wagener JS, et al. Prospective, long term study of fat soluble vitamin status in children with cystic fibrosis identified by newborn screen. J Pediatr. 1999;135:601–610. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heubi JE, Sokol RJ, McGraw C. Comparison of Total Serum Lipids measured by Two Methods. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1990;10:468–472. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199005000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lokitch G, Halstead AC, Quigley G, et al. Age and sex specific pediatric reference intervals: study design and methods illustrated by measurement of serum proteins with the Behrign LN Nephelometer. Clin Chem. 1988;34:1618–1621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whitington PF, Freese DK, Schwarzenberg SJ, et al. Clinical and Biochemical Findings in Progressive Familial Intrahepatic Cholestasis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1994;18:134–141. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199402000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pawlikowska L, Strautnieks S, Jankowska I, et al. Differences in Presentation and Progression Between Severe FIC1 and BSEP deficiencies. J Hepatol. 2010;53:170–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hussain M, Mieli-Vergani G, Mowat A. Alpha One-Antitrypsin Deficiency and Liver Disease: Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis and Treatment. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1991;14:497–511. doi: 10.1007/BF01797920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sokol RJ, Heubi JE, Iannacocone S, et al. Mechanism Causing Vitamin E Deficiency During Chronic Childhood Cholestasis. Gastroenterology. 1983;85:1172–1182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sokol RJ, Kim YS, Hoofnagle JH, et al. Intestinal Malabsorption of Vitamin E in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:479–486. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)91574-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strople J, Glenda L, Heubi JE. Prevalence of Subclinical Vitamin K Deficiency in Cholestatic Liver Disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;49:78–84. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31819a61ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mager DR, McGee PL, Furuya KN, et al. Prevalence of Vitamin K Deficiency in Children with Mild to Moderate Chronic Liver Disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;42:71–76. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000189327.47150.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sokoll LJ, Booth SL, O'Brien ME, Davidson KW, Tsaioun KI, Sadowski J. Changes in serum osteocalcin, plasma phylloquinone, and urinary y-carboxyglutamic acid in response to altered intakes of dietary phylloquinone in human subjects. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1997;65:779–784. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/65.3.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. [Accessed June 9, 2014];Dietary supplement fact sheet: vitamin D. http://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/vitamind.asp. Published June 24, 2011.

- 18.Angelin B, Bjorkhem I, Einarsson K, et al. Hepatic uptake of bile acids in man. Fasting and postprandial concentrations of individual bile acids in portal venous and systemic blood serum. J Clin Invest. 1982;70:724–731. doi: 10.1172/JCI110668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pennington C, Ross P, Bouchier A. Serum Bile Acids in the Diagnosis of Hepatobiliary Disease. Gut. 1977;18:903–908. doi: 10.1136/gut.18.11.903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]