Abstract

Social scientists have long been concerned about how the fortunes of parents affect their children, with acute interest in the most marginalized children. Yet little sociological research considers children in foster care. In this review, we take a three-pronged approach to show why this inattention is problematic. First, we provide overviews of the history of the foster care system and how children end up in foster care, as well as an estimate of how many children ever enter foster care. Second, we review research on the factors that shape the risk of foster care placement and foster care caseloads and how foster care affects children. We close by discussing how a sociological perspective and methodological orientation—ranging from ethnographic observation to longitudinal mixed methods research, demographic methods, and experimental studies—can foster new knowledge around the foster care system and the families it affects.

Keywords: Foster care, child maltreatment, child welfare, Child Protective Services, inequality

INTRODUCTION

How the fortunes of parents shape those of their children is one of the most pressing questions social scientists confront (e.g., Breen & Jonsson, 2005). To that end, researchers have established a vibrant research program considering how parental class and finances (e.g., Blau & Duncan, 1967; Duncan et al., 1994), family structure and parenting (e.g., McLanahan & Sandefur, 1994; Sampson & Laub, 1993), and mobility and neighborhood attainment (e.g., Sampson et al., 2002; Sharkey, 2013; Sharkey & Elwert, 2011) affect children. In a similar vein, they have tested how macro-level shifts in the fortunes of parents shape the life-course for entire cohorts of children (e.g., Elder, 1974 [1998]) and inequality among them (e.g., Wakefield & Wildeman, 2013). Attention to these processes has been particularly sustained for those on the periphery of society. Indeed, from DuBois (1899 [1996]) and Stack (1974) to Wilson (1987) and Desmond (2012b), sociologists have been keenly interested in the intergenerational transmission of social exclusion.

If the presence, fortunes, and behaviors of parents are so consequential for their children, how would we expect the more than 400,000 American children who are currently in foster care2 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012a), who either have no parents, whose parents are no longer their legal caregivers, or who have been temporarily removed from their parents, to fare throughout the life-course?3 The short answer, for better or worse, is that sociologists—and most other social scientists—do not know because they have to date paid little attention to children in foster care. Table 1 demonstrates this inattention in two stages. In the first, Table 1 shows how many articles (and what percentage of all articles) between 1973 and 2012 from the “top three” Sociology, Demography, Economics, Political Science, and Psychology journals included the phrase “foster care” in the full text. We also include the “top three” Social Work journals to show how much attention foster care receives in a discipline where it is central.

Table 1.

Number (%) of Articles on Selected Child Welfare Topics in the “Top Three” Sociology, Demography, Economics, Political Science, Psychology, and Social Work Journals, 1973–2012a

| Foster Care | Infant Mortality | Parental Incarceration | Child Abuse | Corporal Punishment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociology (Total) | 77 (1.1%) | 392 (5.8%) | 2 (0.0%) | 238 (3.5%) | 72 (1.1%) |

| 1973–1982 | 9 (0.4%) | 61 (3.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 43 (2.1%) | 15 (0.7%) |

| 1983–1992 | 4 (0.2%) | 62 (3.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 57 (3.4%) | 14 (0.8%) |

| 1993–2002 | 55 (3.3%) | 224 (13.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 118 (7.0%) | 29 (1.7%) |

| 2003–2012 | 9 (0.7%) | 45 (3.4%) | 2 (0.1%) | 20 (1.5%) | 14 (1.0%) |

| Demography (Total) | 17 (0.4%) | 1398 (34.5%) | 3 (0.1%) | 29 (0.7%) | 4 (0.1%) |

| 1973–1982 | 1 (0.1%) | 379 (34.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (0.4%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| 1983–1992 | 3 (0.3%) | 484 (47.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 10 (1.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| 1993–2002 | 4 (0.4%) | 348 (30.6%) | 1 (0.1%) | 12 (1.1%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| 2003–2012 | 9 (1.1%) | 187 (23.8%) | 2 (0.3%) | 3 (0.4%) | 2 (0.3%) |

| Economics (Total) | 12 (0.1%) | 162 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 14 (0.1%) | 6 (0.1%) |

| 1973–1982 | 1 (0.0%) | 22 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| 1983–1992 | 1 (0.0%) | 31 (1.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| 1993–2002 | 2 (0.1%) | 51 (1.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 9 (0.3%) | 4 (0.1%) |

| 2003–2012 | 8 (0.4%) | 58 (2.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (0.2%) | 2 (0.1%) |

| Political Science (Total) | 11 (0.2%) | 80 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 42 (0.7%) | 9 (0.2%) |

| 1973–1982 | 1 (0.1%) | 13 (0.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (0.2%) | 3 (0.2%) |

| 1983–1992 | 2 (0.1%) | 20 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 16 (1.1%) | 4 (0.3%) |

| 1993–2002 | 7 (0.4%) | 24 (1.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 17 (1.1%) | 2 (0.1%) |

| 2003–2012 | 1 (0.1%) | 23 (1.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 6 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Psychology (Total) | 121 (0.9%) | 88 (0.7%) | 3 (0.0%) | 445 (3.4%) | 66 (0.5%) |

| 1973–1982 | 12 (0.4%) | 16 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 46 (1.3%) | 24 (0.7%) |

| 1983–1992 | 33 (0.9%) | 25 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 134 (3.7%) | 9 (0.3%) |

| 1993–2002 | 28 (0.9%) | 27 (0.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 174 (5.7%) | 17 (0.6%) |

| 2003–2012 | 48 (1.7%) | 20 (0.7%) | 3 (0.1%) | 91 (3.2%) | 16 (0.6%) |

| Social Work (Total) | 2048 (28.6%) | 139 (1.9%) | 49 (0.7%) | 2040 (28.5%) | 113 (1.6%) |

| 1973–1982 | 198 (13.4%) | 19 (1.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 135 (9.1%) | 9 (0.6%) |

| 1983–1992 | 332 (19.4%) | 46 (2.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 38 (22.2%) | 18 (1.0%) |

| 1993–2002 | 470 (30.8%) | 41 (2.7%) | 4 (0.3%) | 529 (34.7%) | 12 (0.8%) |

| 2003–2012 | 1048 (42.8%) | 33 (1.3%) | 45 (1.8%) | 996 (40.7%) | 74 (3.0%) |

Articles are to be considered on a topic if they mentioned the topic anywhere in the full text. We considered American Journal of Sociology, American Sociological Review, and Social Forces for Sociology, Demography, Population and Development Review, and Population Studies for Demography, American Economic Review, Journal of Political Economy, and Quarterly Journal of Economics for Economics, American Journal of Political Science, American Political Science Review, and Journal of Politics for Political Science, Psychological Bulletin, Psychological Review, and American Psychologist for Psychology, and Children and Youth Services Review, Social Service Review, and Social Work for Social Work. Although Annual Review of Sociology is one of the “big three” Sociology journals, we omit it from the list and put Social Forces into the “top three” in its place because we thought this article being commissioned likely indicated the foster care system had received relatively little attention in Annual Review of Sociology, biasing our results toward too few articles. “Foster care” appeared in the text of five Annual Review of Sociology articles from 1973–2012.

According to our estimates, 1.1% of all articles in the “top three” Sociology journals mentioned foster care anywhere in the text from 1973–2012. The share of all Sociology articles mentioning foster care anywhere in the text was between three and ten times that of Demography (0.4%), Economics (0.1%), and Political Science (0.2%) and about comparable to Psychology (0.9%). In Social Work, where children who are in foster care and the foster care system are far more central to the discipline, 28.6% of articles published from 1973–2012 mentioned foster care.

Table 1 also shows how the number of articles mentioning foster care compares to the number of times four other events also consequential for child well-being—infant mortality, parental incarceration, child abuse, and corporal punishment—are mentioned. Foster care received far greater attention over this period than parental incarceration (0.0%), but it received far less attention than infant mortality (5.8%) and child abuse (3.5%).4 For child abuse, this trend did not extend to Social Work, where attention to foster care and child abuse was similar, likely because researchers in Social Work see child maltreatment and foster care placement as linked. To further contextualize this result, consider that corporal punishment (1.1%), an often far less serious negative parenting behavior, received as much attention in Sociology as foster care did.

In this review, we take a three-pronged approach to showing why inattention to the foster care system and the children who end up in it is problematic and, in so doing, call for more research by sociologists on foster care. First, we provide overviews of the history of foster care, how children end up in foster care, and how many children ever enter foster care. Second, we review research on the factors that shape the risk of foster care placement and foster care caseloads and how foster care affects children. Here, we briefly draw connections to two vibrant areas in sociological research. First, we tie research on foster care to the emergent literature on parental incarceration, which, like foster care placement, is far more common for minority children than often thought (e.g., Wildeman, 2009) and may affect them in countervailing ways (e.g., Turney & Wildeman, Forthcoming; Wildeman, 2010), suggesting potentially complex effects on inequality among children. Second, we draw connections to the sociological literature on the social networks of the urban poor (e.g., Desmond, 2012a; Stack, 1974) and how network disruption may affect their subsequent life-chances (e.g., Kirk, 2009; Sampson & Laub, 1993) in order to demonstrate how the sociological perspective can inform understanding of how the network disruptions caused by foster care placement will affect children (Desmond, 2012a:1305; Perry, 2006). We close by discussing how a sociological perspective and, as significantly, methodological orientation could foster new knowledge around the foster care system and the children, families, and communties it affects. By providing this call for sociological research on the foster care system, we hope to enliven the dialogue around adoption already taking place in sociology (e.g., Fisher, 2003; Hamilton et al., 2007), broaden discussion about the processes that may influence the intergenerational transmission of social exclusion and disadvantage, and provide insight into whether foster care exacerbates, ameliorates, or has no effect on inequality.

HISTORY, FROM REFERRAL TO PLACEMENT, AND HOW MANY CHILDREN History5

The child protection, foster care, and adoption systems did not take on their modern form until 1974 with the passage of the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act. Nonetheless, three key events in the history of child protection preceded the mid-1970s. First, Henry Bergh and Elridge Gerry founded the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children in 1875, the first society of its kind. Around 300 parallel organizations quickly sprung up (Myers, 2008:451–452). Second, the Social Security Act of 1935 greatly extended the power of the Children’s Bureau, authorizing it “to cooperate with state public-welfare agencies in establishing, extending, and strengthening, especially in predominantly rural areas, [child welfare services] for the protection and care of homeless, dependent, and neglected children, and children in danger of becoming delinquent” (quoted in Myers, 2008:453). Finally, with the “discovery” (Pfohl, 1976) of child abuse in the 1960s,6 spurred on by a series of highly influential articles on the topic (e.g., Kempe et al., s1962), the public became prepared to act in the interest of maltreated children.7

Pressures created by the growing visibility of child maltreatment led to the passage of the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act of 1974, which established the National Center on Child Abuse and Neglect and sought to improve the monitoring and response to maltreatment.8 Of the legal changes that followed, most focused on two tensions: (1) between family preservation and child safety; and (2) between quicker placement with different-race families and slower placement with same-race families. The Adoption Assistance and Child Welfare Act of 1980, for instance, required states make a “reasonable effort” not to remove children from their homes and reunite them with their parents if they had removed them. In the eyes of critics, the emphasis on family preservation fundamentally went against the goal of Child Protective Services, putting children in the face of unthinkable harm by keeping them with their families (e.g., Bartholet, 1999; Gelles, 1997).9 The Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997 sought to shift the emphasis from family preservation to child safety and, to that end, imposed limits on how long children could be in foster care before parental rights were terminated and allowed states to rapidly remove children from homes in which maltreatment was severe or chronic.

Similar tensions exist surrounding race. These tensions are especially pointed for Native Americans, as upwards of 25% to 35% of Native American children were placed in care prior to the 1970s (Myers, 2008:457). Concern about these high removal rates and placement with non- Native American families led to the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978,10 which had two key stipulations. First, for children living on a reservation, only a tribal court had the authority to place that child in foster care. Second, for Native American children not living on a reservation, Child Protective Services was required to contact the tribe of an impending (or recent) placement, which could intervene in the case. For other children, racial matching preferences have been contentious, as the Multiethnic Placement Act of 1994 stipulated that although race could be a factor in a placement decision, it could not delay the process of finding a foster child a home. Racial matching is an especially salient concern since the number of African American and Native American children in care far exceeds the number of available same-race foster homes.

Turning now to caseloads, American foster care caseloads between 1962 and the present can be divided into three eras. First came the period of relative stability from 1962 to 1985, where the number of children in foster care increased from 272,000 in 1962 to 330,000 in 1971 before tailing off to 262,000 by 1982 (U.S. House of Representatives, 2000:719–720). Second came a period of rapid increase in foster care caseloads from 262,000 in 1982 to nearly 570,000 in 1999. Then came a period of decline to a low of about 400,000 in 2011 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012c). Historical trends in racial disproportionality in the foster care system are harder to track because the Adoption and Foster Care Analysis Reporting and Surveillance System (AFCARS) data did not include the majority of states until roughly 2000. Nonetheless, there is little disagreement that racial disparities in foster care are long-standing.

From Referral to Placement

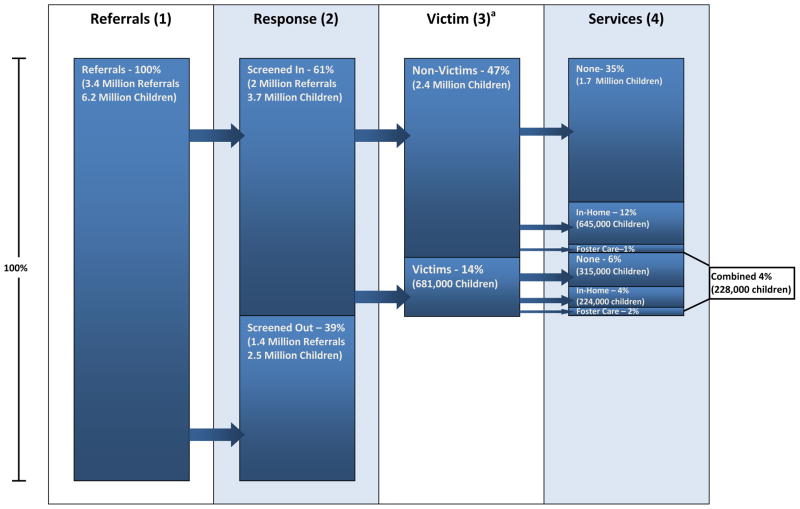

How do children end up in foster care? In Figure 1, we show how children end up in foster care, using 2011 as the sample year.11 In 2011, there were 3.4 million referrals, representing 6.2 million children (Stage 1). Of these 3.4 million referrals, 2.0 million—representing roughly 61% of all referrals and 3.7 million children—received some response from Child Protective Services. The other 1.4 million referrals, representing roughly 39% of all referrals and 2.5 million children, were screened out, meaning that these cases received no additional attention (Stage 2). Of the 3.7 million children who received an investigation, 681,000 were confirmed to have been victims of maltreatment12 and roughly 2.4 million were not determined to have been victims (Stage 3).

Figure 1. Flow of Children through Child Protective Services.

Note: Adapted from U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2013:xi).

a All victim determinations refer to unique victims (meaning that each child could only be counted as a victim once). Referrals, response, and services all refer to duplicate children (meaning children could be counted more than once). Because of this, percentages calculated for Stage 3 and Stage 4 are approximations of the final share of the population included in these categories and are not equivalent to the number divided by 6.2 million.

It is at this point that foster care placement becomes more complicated, as some children determined to be victims received no services, while some children not determined to be victims did. Of the 681,000 children determined to be victims, 315,000 received no services, 224,000 received in-home services, and only 134,000 were placed in foster care. Thus, 2% of children referred to Child Protective Services were confirmed to be victims of maltreatment and placed in foster care. Of the 2.4 million children not confirmed to be victims, 1.7 million received no services, 645,000 received in-home services, and 89,000 were placed in care. Of these 89,000 children, most were removed because they were considered at risk (often due to maltreatment of a sibling), had their parents ask for the child to be removed, or were determined to have service needs better provided in foster care.13 Thus, 4% of all referrals ended up in foster care (Stage 4).

How Many Children Ever Enter Foster Care

With just under 74,000,000 children in the population, under one percent of children enter foster care each year. In light of how few children enter foster care annually, it would be reasonable to wonder how, if at all, the foster care system is important for American society. And, indeed, this concern may partially explain why sociologists have mostly ignored foster care. Yet the daily risk of foster care placement accumulates not just over any year, but also over the course of childhood, meaning that far more children may ever enter foster care than do so annually.

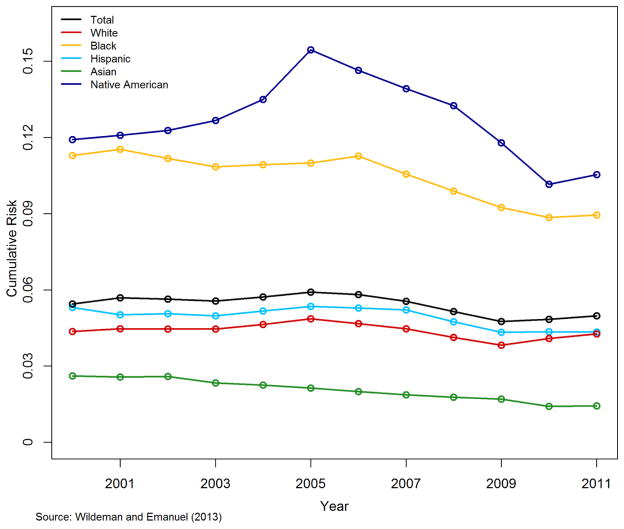

Some research has moved from considering point-in-time risks of foster care placement to cumulative risks of placement using demographic techniques like life tables. Using birth cohort life tables and registry data from California, for instance, Emily Putnam-Hornstein et al. (2013) show that although only 0.5% of children enter foster care annually, by age five, 2.2% of children have ever been placed. African American children (6.2%) are than twice as likely to ever end up in foster care as white children (2.4%).14 In a similar vein, Wildeman and Emanuel (2013) use data from the Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS) and synthetic cohort life tables to estimate what proportion of American children can expect to be placed in foster care by age 18 for each year from 2000 to 2011. The results from this analysis support two conclusions (Figure 2). First, 5% of American children will ever be placed in foster care. Second, Native American (12 to 15%) and African American (9 to 12%) children are far more likely than Hispanic (5%), White (4%), and Asian (2%) children to ever enter care before age 18, suggesting that if foster care placement harms children, the foster care system could play a more significant role in social stratification than is typically imagined because of the large proportion of children who ever enter care and the vast racial disparity in the risk of doing so.

Figure 2. Cumulative Risk of Foster Care Placement by Age 18.

THE CAUSES AND CONSEQUENCES OF PLACEMENT

The Causes of Placement and Foster Care Caseloads

A vast literature considers the causes of child maltreatment (e.g., Belsky, 1993; Garbarino, 1977; Gilbert et al., 2009b:71–72). This body of work links the risk of child maltreatment with a host of child characteristics such as age, disability status, and gender (e.g., Gilbert et al., 2009b:71); parental and familial characteristics such as race, education, socioeconomic status, family structure, domestic violence, and drug use (e.g., Berger et al., 2009b; Berger & Waldfogel, 2011; Cancian et al., 2010; Gilbert et al., 2009b; Kruttschnitt et al., 1994; Sullivan & Knutson, 2000; Taylor et al., 2009); and also to various neighborhood-level characteristics (e.g., Andersen, 2010; Coulton et al., 1999; Drake & Pandey, 1996; Freisthler, 2004; Garbarino & Sherman, 1980).

The body of research considering the causes of foster care placement, on the other hand, is smaller. It also comes with an added difficulty. As Figure 1 shows, the process of foster care placement begins with (1) a referral and then moves on to (2) an investigation which might lead to (3) a substantiated case and, eventually, (4) foster care placement. In this case, is the outcome of interest the probability of being placed in foster care [p(4)] or the probability of being placed in foster care contingent on having a substantiated case [p(4|3)] or an investigation [p(4|2)] or just a referral [p(4|1)]? Unfortunately, most individual-level studies use having an investigation [p(4|2)] or a substantiated case [p(4|3)] as the reference cell (e.g., Berger et al., 2010), while most macro-level studies of the causes of foster care caseloads use no reference cell, predicting only caseloads (e.g., Swann & Sylvester, 2006), so if the results from micro- and macro-level analyses consistently diverged, it would be difficult to know which best captured the process. Thankfully, the micro- and macro-level findings tend to dovetail nicely, so we discuss them jointly.15

Children are supposed to be placed in foster care because the maltreatment they face is severe, chronic, or unlikely to stop. As such, we would expect the best predictors of foster care placement to be the severity and chronicity of maltreatment, as well as factors that drive them. Research finds that in addition to the severity and chronicity of maltreatment, many of the factors (e.g., Gilbert et al., 2009b:71–72), such as parental substance use and abuse, that drive children’s maltreatment risks also drive their foster care placement risks (e.g., Berger et al., 2010; Berger & Waldfogel, 2004; Cunningham & Finlay, 2013; Lery, 2009; Swann & Sylvester, 2006).

Social welfare policies, criminal justice policies, and child welfare policies may also shape foster care caseloads. In each domain, a vital shift took place in the last 20 years: welfare reform; the prison boom, and the Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997. Decreases in welfare generosity, for instance, are associated with increases in the number of substantiated cases of maltreatment (e.g, Paxson & Waldfogel, 2002; 2003)16 and foster care caseloads (e.g., Swann & Sylvester, 2006; Waldfogel, 2004). Increases in female imprisonment associated with the prison boom played a strong role in the increase in foster care caseloads between the mid-1980s and the early 2000s by leaving many children without their primary caregivers. Some accounts even imply that increases in the female imprisonment rate explain one-third of the doubling of foster care caseloads over this period (Swann & Sylvester, 2006:323), a massive effect. There are reasons to question whether increases in female imprisonment had a true causal effect on foster care caseloads, especially since there is no strong micro-level test of the relationship between maternal imprisonment and foster care placement (e.g., Johnson & Waldfogel, 2002). Still, given the provision in the Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997 that parental rights be terminated (absent extenuating circumstances) when a child had been in foster care for 15 of the last 22 months, it would be surprising if maternal imprisonment had no effect on children’s risk of foster care placement (e.g., Swann & Sylvester, 2006:311–312). However, despite great interest in the effect of the Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997 on children of incarcerated parents, very little other research rigorously evaluates its effects on foster care caseloads. Thus, of social policy changes affecting child welfare, nearly all research to date has focused on testing the effects of policy shifts peripherally related to child welfare rather than directly related to it.

Research on the relationship between macro-level policy shifts and foster care caseloads is as notable for what it does not study as for what it does. Most striking is the absence of studies on the effects of policy shifts on racial disparities in foster care. Although African American women experienced far greater (absolute) increases in imprisonment as a result of the prison boom, for instance, no research tests whether the prison boom had an effect on racial inequality in foster care. This gap is endemic to all macro-level research on foster care, which more often than not ignores race—with the exception of including race as a control variable. However, a great deal of research seeks to explain racial disparities in the risk of foster care placement at the individual level, with special attention to African American (e.g., Knott & Donovan, 2010; Miller et al., Forthcoming) and Native American (e.g., Trocmé et al., 2004) children. Much, although not all, of the research on the factors that contribute to racial disproportionality in foster care outside of social work comes from the legal, medical, or public health communities (e.g., Appell, 1996; Hampton & Newberger, 1985; Lane et al., 2002; Roberts, 2002; 2012; Rosner & Markowitz, 1997). Legal scholarship points to the possible role of structural racism. Medical and public health research documents the fact that no matter what controls are included in the model, the placement risks of minority children are always higher than those of otherwise similar White children. Given the dramatic racial disparities in the cumulative risks of foster care placement that we showed in Figure 2, knowing the causes of this racial disproportionality is essential.

In closing, it is worth noting that few of the tests reviewed in this section offer causal evidence (but see Cancian et al., 2010; Cunningham & Finlay, 2013), making it difficult to differentiate causes and correlates. Indeed, Gilbert et al.’s (2009b:72) assessment of the causes of maltreatment applies equally to foster care: “Poverty, mental-health problems, low educational achievement, alcohol and drug misuse, and exposure to maltreatment as a child are strongly associated with parents maltreating their children. The extent to which each of these risk factors is causally related to the occurrence of maltreatment is hard to establish.” Given the lack of causal evidence in this area, a key task for future research is to provide reliable estimates of what factors cause foster care placement, shifts in caseloads, and racial disproportionality in both.

How Foster Care Affects Children

Like other vulnerable populations (e.g., Osgood et al., 2010), children who have ever been in foster care struggle with a host of problems throughout the life-course. These include, but are not limited to, mental health problems as children (e.g., Chisholm, 1999; Pears et al., 2006:69), as well as high rates of homelessness (e.g., Park et al., 2004), criminal justice contact (e.g., Jonson-Reid & Barth, 2000), and sex work (e.g., Ahrens et al., 2012) as adolescents and young adults. They also have poor educational outcomes and employment records (e.g., Pecora et al., 2006), and have more mental and physical health problems (e.g., Zlotnick et al., 2012) later in life.

Given the wealth of insults children in foster care suffer even prior to placement, it is no surprise they go on to struggle mightily throughout childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. And, indeed, this is the fundamental difficulty in estimating the effect of foster care placement on children: Maltreated children—whether or not they go into foster care—suffer from a host of poor outcomes (for an overview, see Gilbert et al., 2009b). Maltreated children are more likely to smoke during adolescence and early adulthood (e.g., Anda et al., 1999), attempt suicide (e.g., Dube et al., 2001), engage in crime and delinquency (e.g., Currie & Tekin, 2012; Widom, 1989), exhibit symptoms consistent with psychopathology (e.g., Molnar et al., 2001), and have higher rates of unintended (e.g., Dietz et al., 1999) and teen (e.g., Elders & Albert, 1998) pregnancy, as well as more unstable relationships (e.g., Cherlin et al., 2004). And this is to say nothing of their high mortality rates (e.g., Putnam-Hornstein et al., Forthcoming). Thus, children who enter foster care already have poorer outcomes than their non-maltreated peers. For example, children have been found to be in poorer health upon foster care entry (e.g., Chernoff et al., 1994; Hochstadt et al., 1987; Needell & Richard, 1998) and to exhibit mental and physical health problems during their time in care that may have preceded placement (e.g., dosReis et al., 1994; Takayama et al., 1994), suggesting foster care may or may not have been a causal factor in their poor outcomes.

Before reviewing research that attempts to tease out the effects of foster care placement on children, five preliminary statements are in order. First, no research provides robust estimates of the effect of foster care placement on subsequent maltreatment, a perplexing gap since the goal of placing children in care is to buffer them from further abuse and neglect. Second, much of the research on the effects of foster care placement on children uses select samples (such as intravenous drug users) to see how foster care accounts for variations in that group (such as age of onset of intravenous drug use). Although such studies are vitally important for practitioners working with these populations, they do not provide generalizable estimates and we therefore do not consider these studies. Third, although the effects of foster care placement likely differ across children (by age, sex, and race/ethnicity, for instance) and across outcomes, a point we return to later, we focus primarily on research estimating the average effects of foster care placement on children because considering moderators and outcome-specific effects would be beyond the scope of this review. Fourth, although little research considers the mechanisms through which foster care placement affects children and, hence, we too provide little attention to mechanisms, some sociological research suggests that network disruption may be an especially important mechanism, as foster care placement massively alters the social networks of children placed in non-kin care (e.g., Desmond, 2012a:1305; Perry, 2006). Yet sociological research provides competing ideas of how this network disruption might affect children. Classic sociological research suggests that social ties are both necessary and sustaining, if in complex ways, for the 15 urban poor (e.g., Stack, 1974), while more recent research suggests that life-course outcomes may improve in some instances when problematic social ties are severed (e.g., Kirk, 2009; Sampson & Laub, 1993). Finally, we focus exclusively on four exceptionally methodologically rigorous studies that go to great lengths to address selection bias in assessing the effects of foster care placement on children (Berger et al., 2009a; Doyle, 2007; 2008; Wald et al., 1988).17,18 Thus, we exclude some of the earlier landmark studies in this area that were less able to address the substantial obstacles to causal inference (e.g., Fanshel & Shinn, 1978; Maas & Engler, 1959).

Crucially, all four of these studies have another key feature: they use children who have come to the attention of Child Protective Services (but not been placed) as the reference cell. Focusing on research on how foster care placement affects the wellbeing of children who have come to the attention of Child Protective Services means that the studies reviewed here provide no insight into alternate reference cells such as being in a home characterized by abuse or neglect but not brought to the attention of Child Protective Services. They also provide little insight into how the different treatments maltreated children could receive, such as being placed with a family or in an institution (e.g., Smyke et al., 2010; Windsor et al., 2011) or left in the home but having their parents receive services (e.g., Olds et al., 1997; 1998) might affect their wellbeing.

In a path-breaking early study, Wald et al. (1988) used a shock in the risk of placement introduced by one county piloting a family preservation model (which dramatically decreased the probability of placement in that county) and a difference-in-difference framework to assess the effects of foster care placement on children. After following the children for two years, they found few differences between the treatment and control groups and, maybe more importantly, that the children who were placed in foster care were actually even slightly advantaged relative to the children who remained in their homes. Although the number of observations is quite small (for most analyses, N = 19 for in-home care, N = 13 for foster care), the strong research design suggests significant weight be placed on their findings. Nonetheless, as the main results exclude Black and Hispanic children, it is unclear whether these results generalize to those populations.

The results from the next attempt to isolate causal effects of foster care placement on children (Doyle 2007, 2008) considerably diverge from the largely null and (even in some cases) positive effects Wald et al. (1978) found. Using rotational assignment of caseworkers in Illinois, which effectively randomizes families to investigators, making it possible to identify causal effects of foster care placement for the marginal child, and administrative data on children’s subsequent outcomes, Doyle considers two sets of outcomes: juvenile delinquency, teen motherhood, and employment in adolescence (2007); and crime in early adulthood (2008). In both cases, Doyle (2007, 2008) finds that placement of the marginal child increases–often markedly—the risk of experiencing negative life course outcomes (such as teenage motherhood and adult crime) while simultaneously impeding positive life course outcomes (such as earnings).

In the fourth study, Berger et al. (2009) used data from the National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being (NSCAW), the first nationally representative longitudinal dataset of children that come into contact with Child Protective Services, to consider the effects of foster care placement on children’s developmental outcomes. They find that the strong, positive descriptive relationship between foster care placement and internalizing and externalizing behaviors disappears entirely for internalizing behaviors and becomes inconsistent—statistically significant in some models, insignificant in others—once stable traits are taken into account. It remains consistently statistically insignificant for both once matched samples are used. For the other outcomes considered, any statistically significant harmful effect of foster care on children disappeared in even simpler models. Based on the most rigorous study to consider the effects of foster care placement using nationally representative data, therefore, the effects appear to be null.

Unfortunately, limiting our review to four of the most methodologically rigorous studies (Berger et al., 2009a; Doyle, 2007; 2008; Wald et al., 1988) does not yield consistent results. Of the most rigorous research considering the effects of foster care placement on children, studies using one dataset show dramatic harm (Doyle, 2007; 2008); those using another dataset show no discernible effects (Berger et al., 2009a); and those using another dataset suggest some benefits (Wald et al., 1988). Although on first glance, these findings might seem incompatible, carefully considering the research designs of the four studies partially reconciles them. For while Doyle’s (2007; 2008) analysis focused on the marginal child—a child who would be placed in foster care by some caseworkers and left in the home by others—the studies by Berger et al. (2009a) and Wald et al. (1988a) estimate effects using a broader swath of children who came into contact with Child Protective Services (and therefore including many children who are suffering more extreme harm at home and who therefore could benefit more from placement). Even though these findings can be reconciled, it may still be worth using methods such as models that allow for heterogeneous treatment effects (e.g., Brand & Xie, 2010), in order to better understand when being placed in foster care helps, hurts, or has no effect on children. Better understanding these effects is vital because although there are substantial racial disparities in the risk of foster care placement, the implications of foster care for inequality remain opaque until we know how it affects children. And, indeed, even if the average effects are null, foster care could have still large effects on inequality in the face of effect heterogeneity (e.g., Wildeman & Muller, 2012).

WHAT SOCIOLOGY CAN ADD

The Sociological Perspective

So what can sociologists bring to this topic beyond what research in Economics, Psychology, Medicine, and Social Work has brought? In this section, we highlight just three components of the distinctly sociological perspective that are likely to enrich the study of foster care.

A vast research literature in sociology focuses on how social problems cluster in space (e.g., Wilson, 1987). Although little research on foster care tests the degree to which foster care overlaps with other ills such as homicide (e.g., Papachristos et al., 2013), infant mortality (e.g., Morenoff, 2003), or incarceration (e.g., Sampson & Loeffler, 2010), it likely does. Largely missing from existing research on foster care are theoretical concepts that could explain this clustering. Sociological concepts such as collective efficacy (e.g., Sampson et al., 1997) or legal cynicism (e.g., Kirk & Papachristos, 2011) could better explain this spatial clustering, as well as how neighborhood changes (beyond shifts in economic factors) might alter foster care caseloads.

Of the research on racial disproportionality19 in the child welfare system, most is either conducted by medical doctors, social workers, or legal scholars, making much of this research very empirical or very theoretical, but rarely both. A key benefit to the sociological perspective is the desire to bridge those two. Consider, for example, recent research on the American penal system. In one compelling recent example, Muller (2012) links racial disparities in incarceration to the Northward migration of Southern blacks between 1880 and 1950, finding not only that this migration dramatically increased black-white disparities in incarceration, but also that these changes are partially attributable to racial threat models proposed by Blalock (1967). Analyses of disproportionality in foster care that follow Muller’s (2012) lead by rigorously testing multiple theoretical frameworks—each situating foster care as an institution with one foot in child protection, the other in social control—would represent a key advance by demonstrating how the uniquely theoretical and empirical sociological perspective can enhance the study of foster care.

One final way in which the sociological perspective could enliven research on foster care is to push it to think more expansively about what inequality is,20 why it matters, and whether foster care solely reflects inequality or also contributes to it. As we noted in the introduction to this article, the degree to which the fortunes of parents shape those of their children is absolutely central to the sociological perspective, as is the degree to which such processes may exacerbate social inequality. Yet this is an idea that research on foster care has currently wrestled with only a small amount—likely because most researchers of the foster care system are acutely interested in the lives of individual children. By focusing on whether the foster care system creates or merely reflects social inequality—and especially whether any inequality it creates is durable (Tilly, 1999)—the study of foster care would be greatly enhanced. Here, research on foster care might follow the lead of research on the consequences of mass imprisonment for racial inequality among not only adult men (Western, 2006) but also children (Wakefield & Wildeman 2013).

While the sociological perspective can—and should—add a great deal to the study of foster care, it is important for sociologists to master the impressive literature on foster care before deciding on what the core contribution of the sociological perspective might be. This will also involve, at a minimum, taking a cue from other distinct disciplinary perspectives. For example, a sociology of foster care that focused solely on estimating average effects of foster care on children without paying attention to existing research in developmental psychology on the various factors that might moderate these effects or how these effects might differ by child age or across outcomes would be far poorer for that inattention to other disciplinary perspectives.

The Sociological Methodological Orientation

As much as the sociological perspective adds to the study of foster care, the contributions of the sociological methodological orientation may be even greater. In this section, we discuss how a combination of ethnographic observation, longitudinal mixed methods research, demographic methods, and experimental studies could pave the way for a vibrant new sociology of foster care. Before doing so, we echo prior research in noting that the longitudinal data available to analyze the effects of foster care placement on children are still woefully inadequate (e.g., Waldfogel, 2000), making it difficult, for instance, for analysts to estimate effects of foster care placement relative to being maltreated but not coming to the attention of Child Protective Services.

In the introduction, we listed several ethnographic studies that enhanced understanding of the contexts in which the urban poor make decisions and the myriad factors contributing to the intergenerational transmission of social exclusion (e.g., Desmond, 2012b; DuBois, 1899 [1996], Stack, 1974). For scholars interested in inequality, such studies are the natural counterpart to quantitative research on this population, and it is only by marrying the quantitative with the qualitative that we gained a more complete understanding of these social processes. Such methods were especially useful, for instance, for studying severely vulnerable populations such as women who had recently been evicted (Desmond, 2012). And ethnographic methods might thus prove especially valuable with such a severely marginalized population as children in foster care. With few exceptions (e.g., Schwartz, 2004), however, research on foster care has been dominated by quantitative research, limiting our understanding and making it impossible for us to fully grasp the inner workings of the foster care system. Ethnographic studies similar to those of medical professionals (e.g., Bosk, 1979) or bench scientists (Latour & Woolgar, 1979 [1986]) would therefore be an especially welcome addition to research on the foster care system.

If ethnographic methods could provide especially vital insights into the decision-making process in the foster care system, marrying qualitative and quantitative data within a longitudinal context might prove to be an especially fruitful method for understanding the long-term effects of foster care placement on children (for a broader discussion of conducting mixed-methods research, see especially Small, 2011). Although undertaking such a novel study would almost certainly be difficult because of the dearth of existing quantitative longitudinal data on children placed in foster care, recent research on the trajectories of crime among juvenile delinquents in a historical dataset provides insight both into how to accomplish such a study—by combining the sophisticated data analysis techniques and life-history interviews with the subjects they could track down—and what a tremendous impact such a study could have (Laub & Sampson, 2004). No other discipline is nearly as well-suited for undertaking such an important study as sociology.

Of course, what is so distinctive about the sociological methodological orientation is the union of qualitative and quantitative methods, and we have thus far not mentioned contributions that might be made by quantitative researchers. The traditional life table—also known as the single decrement life table—treats individuals as moving through the life-course at risk of only one event (e.g., death). Some applications of the single decrement life table to the study of foster care have been discussed earlier (Putnam-Hornstein et al., 2013; Wildeman & Emanuel, 2013), but there are extensions of the traditional life table such as the multiple decrement life table, which treats individuals as at risk not of one event (e.g., death) but multiple events (e.g., death by stroke, suicide, or homicide) (e.g., Preston et al., 2001:71–91). For children at risk of entering foster care, who are also at a host of other risks (as reviewed extensively here), a descriptive method that captures the full spectrum of events they might experience seems especially ideal.

The final series of ways in which sociologists can contribute to the study of foster care would apply the experimental tradition in sociology (e.g., Jackson & Cox, 2013), which includes natural experiments (e.g., Berk et al., 1992; Sherman & Berk, 1982) and audit studies (e.g., Correll et al., 2007; Pager, 2003), to the study of foster care. In this vein, researchers might study how experimentally varying the proportion or type of children placed in foster care affects subsequent child wellbeing (e.g., Wald et al., 1988). Or they could, for instance, examine how racial bias contributes to racial disproportionality in foster care by using an audit study design and experimentally varying child race to evaluate how race affects caseworker decisions.

CONCLUSION

Social workers, doctors, legal scholars, psychologists, and economists have produced an impressive body of knowledge on foster care, but contributions from sociologists have been notably absent (for two recent examples of sociological research on this topic, see Perry, 2006; Swartz, 2004). In this essay, we argued that this inattention from the sociological community is a mistake not just because the foster care system is an inherently interesting social institution and that children who spend time in foster care are an inherently important group, but also because of the unique contribution sociology, with its rich theoretical tradition and vast methodological diversity, could make to research in this area. In so doing, we hope to have simultaneously caught sociologists up to speed on extant research and motivated them to start contributing to it.

Acknowledgments

We thank Julia Adams, Frank Edwards, Valeria Fajardo, Marcus Hunter, Andy Papachristos, Emily Putnam-Hornstein, Chris Muller, Kristin Turney, and Sara Wakefield for their helpful comments. Sara Bastomski, Tony Cheng, and Natalia Emanuel provided exemplary research assistance throughout.

Footnotes

According to 45 § 1355.20, “Foster care means 24-hour substitute care for children placed away from their parents or guardians and for whom the title IV–E agency has placement and care responsibility. This includes, but is not limited to, placements in foster family homes, foster homes of relatives, group homes, emergency shelters, residential facilities, child care institutions, and preadoptive homes. A child is in foster care in accordance with this definition regardless of whether the foster care facility is licensed and payments are made by the State, Tribal or local agency for the care of the child, whether adoption subsidy payments are being made prior to the finalization of an adoption, or whether there is Federal matching of any payments that are made.” Thus, children who are living with kin but whose arrangement is not recognized by the state are not living in foster care (e.g., Stack 1974).

Although earlier research in the United States (e.g., Hacsi, 1998; Jones, 1989; 1993) and contemporary research in countries with high rates of parental mortality (e.g., Atwine et al., 2006; Case et al., 2004) focuses on orphans and orphanages, we focus on foster care instead because of its relevance to contemporary American society, where few children enter state care because of parental death or live for any period of time in an institution like an orphanage.

This differential emphasis on child maltreatment is especially pronounced in the medical community. As but one example of this, consider that the Lancet recently featured a four-part article series on child maltreatment in which foster care was rarely mentioned (Gilbert et al., 2009a, 2009b; MacMillan et al., 2009; Reading et al., 2009).

For two excellent and concise histories of child protection, see especially Myers (2008) and Schene (1998). For a broad overview of the past, present, and future of child protection in America, see especially Waldfogel (1998b).

Although the “discovery” (Pfohl, 1976) of child abuse is often seen as taking place in the early 1960s, a small number of medical doctors had started publishing on child maltreatment as early as the 1940s (e.g., Caffey, 1946)

For a thoughtful follow-up to Kempe et al. (1962) 50 years later, see Leventhal & Krugman (2012).

For a more in-depth discussion, including a much longer list of relevant laws, see especially Schene (1998:28).

For an especially acrimonious debate in this regard, see Bartholet (2000) and Guggenheim (2000).

Recent Supreme Court decisions complicate portions of this law, however (Adoptive Couple v. Baby Girl, 2013).

For a significantly more in-depth analysis of how this process works from start to finish, see Schene (1998:31, 33).

Of those confirmed to be victims of maltreatment, roughly 1,600 were deceased as a result of their maltreatment (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012b:xi), meaning they cannot receive any further services.

States vary dramatically, however, not only in foster care caseloads (e.g., Swann & Sylvester, 2006:322), but also in how children move through the system. In Vermont, for instance, the total referral rate (per 1,000) was 110.2 in 2011; in Georgia, the rate was 13.5 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012b:10). States also dealt with referrals in different ways. In Alabama, for instance, nearly all (98.6%) of referrals were screened-in; in Minnesota only 31.3% of referrals were screened-in (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012b:10).

Parallel estimates of the cumulative risk of ever having a substantiated case of child maltreatment also exist for Cuyahoga County, Ohio to age ten (Sabol et al., 2004) and for California to age five (Putnam-Hornstein et al., 2011). For an innovative alternative strategy for estimating child maltreatment rates, see Stephens-Davidowitz (2013).

There are, of course, dramatic variations in the foster care experiences children have. They include, for instance, whether a child is placed in kinship or non-kinship foster care (e.g., Ehrle & Geen, 2002), how long the child is in care (e.g., Benedict & White, 1991; Fallesen, 2013b), and whether the child ages out of care (e.g., Avery, 2010; Courtney & Dworsky, 2006). Although each of these issues is of vital importance for the children, we focus on the more analytically and conceptually straightforward dichotomy between being placed in foster care and not because a broader survey is beyond the scope of this review. Nonetheless, researchers entering this field should be aware of the extensive literature on prevalence, causes, and consequences of variations in the foster care experience.

This finding is buttressed by large micro-level effects of welfare generosity on maltreatment (Cancian et al., 2010).

Although other research (e.g., Warburton et al., 2011) goes to great lengths to address selection, we do not discuss this work because the sample used (16–18 year old males) represents such a small fraction of children entering foster care. We also focus on only one carefully matched study with small sample sizes (e.g., Lawrence et al., 2006) because small sample sizes make it difficult to decipher what to make of statistically insignificant associations.

We also exclude studies on the consequences of foster care placement for parents, although there is now a substantial body of work that also considers these effects (e.g., Fallesen 2013a; Schofield et al. 2011; Sykes, 2011).

Although we emphasize research on racial disproportionality in foster care, there is also a vast literature on income (and class, more broadly) disproportionality in foster with which sociologists could also usefully engage.

Research in this area has thoughtfully considered how to measure inequality in foster care (e.g., Shaw et al., 2008).

Contributor Information

Christopher Wildeman, Yale University.

Jane Waldfogel, Columbia University.

References

- Adoptive Couple v. Baby Girl. 2013. 570 U.S.

- Ahrens KR, Katon W, McCarty C, Richardson LP, Courtney ME. Association Between Childhood Sexual Abuse and Transactional Sex in Youth Aging out of Foster Care. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2012;36:75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anda RF, Croft JB, Felitti VJ, Nordenberg D, Giles WH, Williamson DF, Giovino GA. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Smoking During Adolescence and Adulthood. JAMA. 1999;282:1652–1658. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.17.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen SH. A Good Place to Live? On Municipality Characteristics and Children’s Placement Risk. Social Service Review. 2010;84:201–244. [Google Scholar]

- Appell AR. Protecting Children or Punishing Mothers: Gender, Race, and Class in the Child Protection System. South Carolina Law Review. 1996;48:577–613. [Google Scholar]

- Atwine B, Cantor-Graae E, Bajunirwe F. Psychological Distress Among AIDS Orphans in Rural Uganda. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;61:555–564. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery RJ. An Examination of Theory and Promising Practice for Achieving Permanency for Teens Before They Age Out of Foster Care. Children and Youth Services Review. 2010;32:399–408. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholet E. Nobody’s Children: Abuse and Neglect, Foster Drift, and the Adoption Alternative. Boston, MA: Beacon Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholet E. Reply: Whose Children? A Response to Professor Guggenheim. Harvard Law Review. 2000;113:1999–2008. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. Etiology of Child Maltreatment: A Developmental Ecological Analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:413–434. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedict MI, White RB. Factors Associated with Foster Care Length of Stay. Child Welfare. 1991;70:45–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger LM, Bruch SK, Johnson EK, James S, Rubin D. Estimating the ‘Impact’ of Outof- Home Placement on Child Well-Being: Approaching the Problem of Selection Bias. Child Development. 2009;80:1856–1876. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01372.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger LM, Paxson C, Waldfogel J. Mothers, Men, and Child Protective Services Involvement. Child Maltreatment. 2009;14:263–276. doi: 10.1177/1077559509337255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger LM, Slack KS, Waldfogel J, Bruch SK. Caseworker-Perceived Caregiver Substance Abuse and Child Protective Services Outcomes. Child Maltreatment. 2010;15:199–210. doi: 10.1177/1077559510368305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger LM, Waldfogel J. Out-of-Home Placement of Children and Economic Factors: An Empirical Analysis. Review of Economics of the Household. 2004;2:387–411. [Google Scholar]

- Berger LM, Waldfogel J. OECD Social, Employment, and Migration Work. Pap. No. #111. OECD Publishing; 2011. Economic Determinants and Consequences of Child Maltreatment. [Google Scholar]

- Berk RA, Campbell A, Klap R, Western B. The Deterrent Effect of Arrest in Incidents of Domestic Violence: A Bayesian Analysis of Four Field Experiments. American Sociological Review. 1992;57:698–708. [Google Scholar]

- Blalock HM. Toward a Theory of Minority-Group Relations. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Blau PM, Duncan OD. The American Occupational Structure. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Bosk CL. Forgive and Remember: Managing Medical Failure. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Brand JE, Xie Y. Who Benefits Most from College? Evidence for Negative Selection in Heterogeneous Economic Returns to Higher Education. American Sociological Review. 2010;75:273–302. doi: 10.1177/0003122410363567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen R, Jonsson JO. Inequality of Opportunity in Comparative Perspective: Recent Research on Educational Attainment and Social Mobility. Annu Rev Sociol. 2005;31:223–243. [Google Scholar]

- Caffey J. Multiple Fractures in the Long Bones of Infants Suffering from Chronic Subdural Hematoma. American Journal of Roentgenology and Radium Therapy. 1946;56:163–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancian M, Slack KS, Yang MY. Institute for Research on Poverty Discussion Paper #1385–10. 2010. The Effect of Family Income on Risk of Child Maltreatment. [Google Scholar]

- Case A, Paxson C, Ableidinger J. Orphans in Africa: Parental Death, Poverty, and School Enrollment. Demography. 2004;41:483–508. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ, Burton LM, Hurt TR, Purvin DM. The Influence of Physical and Sexual Abuse on Marriage and Cohabitation. American Sociological Review. 2004;69:768–789. [Google Scholar]

- Chernoff R, Combs-Orme T, Risley-Curtiss C, Heisler A. Assessing the Health Status of Children Entering Foster Care. Pediatrics. 1994;93:594–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm K. A Three Year Follow-Up of Attachment and Indiscriminate Friendliness in Children Adopted from Romanian Orphanages. Child Development. 1998;69:1092–1106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulton CJ, Korbin JE, Su M. Neighborhoods and Child Maltreatment: A Multi-Level Study. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1999;23:1019–1040. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney ME, Dworsky A. Early Outcomes for Young Adults Transitioning from Out-Of- Home Care in the USA. Child and Family Social Work. 2006;11:209–219. [Google Scholar]

- Correll SJ, Benard S, Paik I. Getting a Job: Is There a Motherhood Penalty? American Journal of Sociology. 2007;112:1297–1339. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham S, Finlay K. Parental Substance Use and Foster Care: Evidence from Two Methamphetamine Supply Shocks. Economic Inquiry. 2013;51:764–782. [Google Scholar]

- Currie J, Tekin E. Understand the Cycle: Childhood Maltreatment and Future Crime. Journal of Human Resources. 2012;47:509–549. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmond M. Disposable Ties and the Urban Poor. American Journal of Sociology. 2012a;117:1295–1335. [Google Scholar]

- Desmond M. Eviction and the Reproduction of Urban Poverty. American Journal of Sociology. 2012b;118:88–133. [Google Scholar]

- Dietz PM, Spitz AM, Anda RF, Williamson DF, McMahon PM, et al. Unintended Pregnancy Among Adult Women Exposed to Abuse or Household Dysfunction During Their Childhood. JAMA. 1999;282:1359–1364. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.14.1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- dos Reis S, Zito JM, Safer DJ, Soeken KL. Mental Health Services for Youths in Foster Care and Disabled Youths. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;91:1094–1099. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.7.1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle JJ. Child Protection and Child Outcomes: Measuring the Effects of Foster Care. American Economic Review. 2007;97:1583–1610. doi: 10.1257/aer.97.5.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle JJ. Child Protection and Adult Crime: Using Investigator Assignment to Estimate Causal Effects of Foster Care. Journal of Political Economy. 2008;116:746–770. [Google Scholar]

- Drake B, Pandey S. Understanding the Relationship Between Neighborhood Poverty and Specific Types of Child Maltreatment. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1996;20:1003–1018. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(96)00091-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Chapman DP, Williamson DF, Giles WH. Childhood Abuse, Household Dysfunction, and the Risk of Attempted Suicide Throughout the Life Span. JAMA. 2001;286:3089–3096. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.24.3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuBois WEB. The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1899 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, Klebanov PK. Economic Deprivation and Early Childhood Development. Child Development. 1994;65:296–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrle J, Geen R. Kin and Non-Kin Foster Care—Findings from a National Survey. Children and Youth Services Review. 2002;24:15–35. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH. Children of the Great Depression. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1974 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Elders MJ, Albert AE. Adolescent Pregnancy and Sexual Abuse. JAMA. 1998;280:648–649. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.7.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallesen P. Downward Spiral: The Impact of Foster Care Placements on Paternal Public Dependency. Presented at Annu. Meet. Population Assoc. of America, 78th; New Orleans. 2013a. [Google Scholar]

- Fallesen P. Rockwool Foundation Research Unit Technical Note. 2013b. The Effect of Foster Care Duration on Later Life Outcomes. [Google Scholar]

- Fanshel D, Shinn EB. Children in Foster Care: A Longitudinal Investigation. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher AP. Still ‘Not Quite As Good As Having Your Own’? Toward a Sociology of Adoption. Annual Review of Sociology. 2003;29:335–361. [Google Scholar]

- Freisthler B. A Spatial Analysis of Social Disorganization, Alcohol Access, and Rates of Child Maltreatment in Neighborhoods. Children and Youth Services Review. 2004;26:803–819. [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino J. The Human Ecology of Child Maltreatment: A Conceptual Model for Research. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1977;39:721–735. [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino J, Sherman D. High-Risk Neighborhoods and High-Risk Families: The Human Ecology of Child Maltreatment. Child Development. 1980;51:188–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelles RJ. The Book of David: How Preserving Families Can Cost Children’s Lives. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert R, Kemp A, Thoburn J, Sidebotham P, Radford L, et al. Child Maltreatment 2: Recognising and Responding to Child Maltreatment. Lancet. 2009;373:167–180. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61707-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E, Janson S. Child Maltreatment 1: Burden and Consequences of Child Maltreatment in High-Income Countries. Lancet. 2009;373:68–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guggenheim M. Somebody’s Children: Sustaining the Family’s Place in Child Welfare Policy. Harvard Law Review. 2000;113:1716–1750. [Google Scholar]

- Hacsi TA. Second Home: Orphan Asylums and Poor Families in America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton L, Cheng S, Powell B. Adoptive Parents, Adaptive Parents: Evaluating the Importance of Biological Ties in Parental Investment. American Sociological Review. 2007;72:95–116. [Google Scholar]

- Hampton RL, Newberger EH. Child Abuse Incidence and Reporting by Hospitals: Significance of Severity, Class, and Race. American Journal of Public Health. 1985;75:56–60. doi: 10.2105/ajph.75.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochstadt NJ, Jaudes PK, Zimo DA, Schachter J. The Medical and Psychosocial Needs of Children Entering Foster Care. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1987;11:53–62. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(87)90033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson M, Cox DR. The Principles of Experimental Design and Their Application in Sociology. Annual Review of Sociology. 2013;39:27–49. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson EI, Waldfogel J. Parental Incarceration: Recent Trends and Implications for Child Welfare. Social Service Review. 2002;76:460–479. [Google Scholar]

- Jones MB. Crisis of the American Orphanage, 1931–1940. Social Service Review. 1989;63:613–629. [Google Scholar]

- Jones MB. Decline of the American Orphanage, 1941–1980. Social Service Review. 1993;67:459–480. [Google Scholar]

- Jonson-Red M, Barth RP. From Placement to Prison: The Path to Adolescent Incarceration from Child Welfare Supervised Foster or Group Care. Children and Youth Services Review. 2000;22:493–516. [Google Scholar]

- Kempe CH, Silverman FN, Steele BF, Droegemueller W, Silver HK. The Battered-Child Syndrome. JAMA. 181:17–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.1962.03050270019004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk DS. A Natural Experiment on Residential Change and Recidivism: Lessons from Hurricane Katrina. American Sociological Review. 2009;74:484–505. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk DS, Papachristos AV. Cultural Mechanisms and the Persistence of Neighborhood Violence. American Journal of Sociology. 2011;116:1190–1233. doi: 10.1086/655754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knott T, Donovan K. Disproportionate Representation of African-American Children in Foster Care: Secondary Analysis of the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System. Children and Youth Services Review. 2010;32:679–684. [Google Scholar]

- Kruttschnitt C, McLeod JD, Dornfeld M. The Economic Environment of Child Abuse. Social Problems. 1994;41:299–315. [Google Scholar]

- Lane WG, Rubin DM, Monteith R, Christian CW. Racial Differences in the Evaluation of Pediatric Fractures for Physical Abuse. JAMA. 2002;288:1603–1609. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.13.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latour B, Woolgar S. Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1979 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- Laub JH, Sampson RJ. Shared Beginnings, Divergent Lives: Delinquent Boys to Age 70. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence CR, Carlson EA, England B. The Impact of Foster Care on Development. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18:57–76. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal JM, Krugman RD. ‘The Battered-Child Syndrome’ 50 Years Later: Much Accomplished, Much Left to Do. JAMA. 2012;308:35–36. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.6416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lery B. Neighborhood Structures and Foster Care Entry Risk: The Role of Spatial Scale in Defining Neighborhoods. Children and Youth Services Review. 2009;31:331–337. [Google Scholar]

- Maas HS, Engler RE. Children in Need of Parents. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan HL, Wathen CN, Barlow J, Fergusson DM, Leventhal JM, Taussig HN. Child Maltreatment 3: Interventions to Prevent Child Maltreatment and Associated Impairment. Lancet. 2009;373:250–266. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61708-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S, Sandefur G. Growing Up With a Single Parent: What Hurts, What Helps. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Miller KA, Cashn K, Anderson-Nathe B, Cause AG, Bender R. Children and Youth Services Review. 2013. Individual and Systemic/Structural Bias in Child Welfare Decision Making: Implications for Children and Families of Color. [Google Scholar]

- Molnar BE, Buka SL, Kessler RC. Child Sexual Abuse and Subsequent Psychopathology: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:753–760. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.5.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morenoff JD. Neighborhood Mechanisms and the Spatial Dynamics of Birth Weight. American Journal of Sociology. 2003;108:976–1017. doi: 10.1086/374405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller C. Northward Migration and the Rise of Racial Disparity in America, 1880–1950. American Journal of Sociology. 2012;118:281–326. [Google Scholar]

- Myers JEB. A Short History of Child Protection in America. Family Law Quarterly. 2008;42:449–463. [Google Scholar]

- Needell B, Barth RP. Infants Entering Foster Care Compared to Other Infants Using Birth Status Indicators. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1998;22:1179–1187. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(98)00096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL, Eckenrode J, Henderson CR, Kitzman H, Powers J, et al. Long-Term Effects of Home Visitation on Maternal Life Course And Child Abuse and Neglect. JAMA. 1997;278:637–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL, Henderson CR, Cole R, Eckenrode J, Kitzman H, Luckey D, Pettitt L, Sidora K, Morris P, Powers J. Long-Term Effects of Nurse Home Visitation on Children’s Criminal and Antisocial Behavior. JAMA. 1998;280:1238–1244. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.14.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osgood DW, Foster EM, Courtney ME. Vulnerable Populations and the Transition to Adulthood. Future of Children. 2010;20:209–229. doi: 10.1353/foc.0.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pager D. The Mark of a Criminal Record. American Journal of Sociology. 2003;108:937–975. [Google Scholar]

- Papachristos AV, Hureau DM, Braga AA. The Corner and the Crew: The Influence of Geography and Social Networks on Gang Violence. American Sociological Review. 2013;78:417–447. [Google Scholar]

- Park JM, Metraux S, Culhane DP. Child Welfare Involvement Among Homeless Children. Child Welfare. 2004;83:423–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxson C, Waldfogel J. Work, Welfare, and Child Maltreatment. Journal of Labor Economics. 2002;20:435–474. [Google Scholar]

- Paxson C, Waldfogel J. Welfare Reforms, Family Resources, and Child Maltreatment. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 2003;22:85–113. [Google Scholar]

- Pears KC, Bruce J, Fisher PA, Kim HK. Indiscriminate Friendliness in Maltreated Foster Children. Child Development. 2010;15:64–75. doi: 10.1177/1077559509337891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecora PJ, Kessler RC, O’Brien K, White CR, Williams J, et al. Educational and Employment Outcomes of Adults Formerly Placed in Foster Care: Results from the Northwest Foster Care Alumni Study. Children and Youth Services Review. 2006;28:1459–1481. [Google Scholar]

- Perry BL. Understanding Social Network Disruption: The Case of Youth in Foster Care. Social Problems. 2006;53:371–391. [Google Scholar]

- Pfohl SJ. The ‘Discovery’ of Child Abuse. Social Problems. 1976;24:310–323. [Google Scholar]

- Preston SH, Heuveline P, Guillot M. Demography: Measuring and Modeling Population Processes. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam-Hornstein E, Cleves M, Licht R, Needell B Forthcoming . Risk of Injury Death Following a Report of Physical Abuse vs. Neglect: Evidence from a Prospective, Population-Based Study. American Journal of Public Health. 2013 doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam-Hornstein E, Needell B, King B, Johnson-Motoyama M. Racial and Ethnic Disparities: A Population-Based Examination of Risk Factors for Involvement with Child Protective Services. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2013;37:33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam-Hornstein E, Webster D, Needell B, Magruder J. A Public Health Approach to Child Maltreatment Surveillance: Evidence from a Data Linkage Project in the United States. Child Abuse Review. 2011;20:256–273. [Google Scholar]

- Reading R, Bissell S, Goldhagen J, Harwin J, Masson J. Child Maltreatment 4: Promotion of Children’s Rights and Prevention of Child Maltreatment. Lancet. 2009;373:332–343. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61709-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DE. Shattered Bonds: The Color of Child Welfare. New York, NY: Basic Civitas Books; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts D. Prison, Foster Care, and the Systematic Punishment of Black Mothers. UCLA Law Review. 2012;59:1474–1500. [Google Scholar]

- Rosner D, Markowitz G. Race, Foster Care, and the Politics of Abandonment in New York City. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87:1844–1849. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.11.1844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabol W, Coulton C, Polousky E. Measuring Child Maltreatment Risk in Communities: A Life Table Approach. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2004;28:967–983. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Laub JH. Crime in the Making: Pathways and Turning Points Through Life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Loeffler C. Punishment’s Place: The Local Concentration of Mass Incarceration. Daedalus. 2010;139:20–31. doi: 10.1162/daed_a_00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Gannon-Rowley T. Assessing ‘Neighborhood Effects’: Social Process and New Directions in Research. Annual Review of Sociology. 2002;28:443–478. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and Violent Crime: A Multilevel Study of Collective Efficacy. Science. 1997;277:918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schene PA. Past, Present, and Future Roles of Child Protective Services. Future of Children. 1998;8:23–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield G, Moldestad B, Hojer I, Ward E, Skilbred D. Managing Loss and a Threatened Identity: Experiences of Parents of Children Growing Up in Foster Care, the Perspectives of Their Social Workers and Implications for Practice. British Journal of Social Work. 2011;41:74–92. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw TV, Putnam-Hornstein E, Magruder J, Needell B. Measuring Racial Disparity in Child Welfare. Child Welfare. 2008;87:23–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman LW, Berk RA. The Specific Deterrent Effects of Arrest for Domestic Assault. American Sociological Review. 1984;49:261–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small ML. How to Conduct a Mixed Methods Study: Recent Trends in a Rapidly Growing Literature. Annual Review of Sociology. 2011;37:57–86. [Google Scholar]

- Swartz TT. Mothering for the State: Foster Parenting and the Challenges of Government- Contracted Care Work. Gender and Society. 2004;18:567–587. [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey P. Stuck in Place: Urban Neighborhoods and the End of Progress Toward Racial Equality. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey P, Elwert F. The Legacy of Disadvantage: Multigenerational Neighborhood Effects on Cognitive Ability. American Journal of Sociology. 2011;116:1934–1981. doi: 10.1086/660009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyke AT, Zeanah CH, Fox NA, Nelson CA, Guthrie D. Placement in Foster Care Enhances Quality of Attachment Among Young Institutionalized Children. JAMA. 2010;81:212–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01390.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stack C. All Our Kin. New York, NY: BasicBooks; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens-Davidowitz S. New York Times. 2013. Jul 14, How Googling Unmasks Child Abuse; p. SR5. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PM, Knutson JF. Maltreatment and Disabilities: A Population-Based Epidemiological Study. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2000;24:1257–1273. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00190-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann CA, Sylvester MS. The Foster Care Crisis: What Caused Caseloads to Grow? Demography. 2006;43:309–335. doi: 10.1353/dem.2006.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sykes J. Negotiating Stigma: Understanding Mothers Responses’ to Accusations of Child Neglect. Children and Youth Services Review. 2011;33:448–456. [Google Scholar]

- Takayama JI, Bergman AB, Connell FA. Children in Foster Care in the State of Washington: Health Care Utilization and Expenditures. JAMA. 1994;271:1850–1855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CE, Guterman NB, Lee SJ, Rathouz PJ. Intimate Partner Violence, Maternal Stress, Nativity, and Risk for Maternal Maltreatment of Young Children. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:175–183. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.126722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trocmé N, Knoke D, Blackstock C. Pathways to the Overrepresentation of Aboriginal Children in Canada’s Child Welfare System. Social Service Review. 2004;78:577–600. [Google Scholar]

- Tilly C. Durable Inequality. Berkley, CA: University of California Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Turney K, Wildeman C. American Sociological Review. 2013. Explaining the Countervailing Consequences of Paternal Incarceration for Parenting. Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services. AFCARS Report #19: Preliminary FY 2011 Estimates as of July 2012. Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services; 2012a. http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/afcarsreport19.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services. Child Maltreatment 2011. Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services; 2012b. http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/cm11.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services. Trends in Foster Care and Adoption—FY 2002-FY 2011. Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services; 2012c. http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/trends_fostercare_adoption.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. House of Reps., Committee on Ways and Means. 2000 Green Book: Background Material and Data on Programs within the Jurisdiction of the Committee on Ways and Means. Washington, DC: U.S. House of Reps., Committee on Ways and Means; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield S, Wildeman C. Children of the Prison Boom: Mass Incarceration and the Future of American Inequality. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wald MS, Carlsmith JM, Leiderman PH. Protecting Abused and Neglected Children. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Waldfogel J. Rethinking the Paradigm for Child Protection. Future of Children. 1998a;8:104–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]