Abstract

The objectives of this study were to determine whether, and to what degree, the aqueous iron concentration in the growing medium affects the growth of, and Fe uptake by, Phragmites australis, and whether the presence of iron in the growing environment affects the uptake of the essential element phosphate. The wetland macrophyte P. australis was grown under laboratory conditions in nutrient solution (0·31 mg L–1 phosphate) containing a range of iron concentrations (0–50 mg L–1 Fe). A threshold of iron concentration (1 mg L–1) was found, above which growth of P. australis was significantly inhibited. No direct causal relationship between iron content in aerial tissues and growth inhibition was found, which strongly suggests that iron toxicity cannot explain these results. Phosphate concentrations in aerial tissues were consistently sufficient for growth and development (2–3 % d. wt) despite significant variation in concentration of phosphate associated with roots. External Fe concentration had a significant effect on the growth of P. australis and on both Fe and phosphate concentrations associated with roots. However, neither direct toxicity nor phosphate deficiency could explain the reduction in growth above 1 mg L–1 external Fe concentration

Key words: Iron plaque, iron uptake, nutrient deficiency, phosphate, Phragmites australis, wetlands

INTRODUCTION

The common reed [Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin ex. Steudel] is a helophytic grass, widely occurring in temperate regions of the world. It is usually found in saturated soils and thus colonizes a range of habitats including marshes, fens, shallow lakes and salt marshes (Haslam, 1972). Phragmites australis is often one of the first species to invade areas that have been subjected to disturbance, particularly water pollution. This is due to its ability to withstand environmental stress including the presence of potentially toxic metal contaminants (Schierup and Larsen, 1981; (Van der Werff, 1991). The tolerance of P. australis to heavy metals has been exploited during the last two decades in constructed wetlands designed to treat contaminated mine waters (e.g. Hedin et al., 1994; Lamb et al., 1998; Scholes et al., 1998; Younger et al., 2002). The concentrations of metals in waters treated by such systems may vary greatly; in the case of iron (the major contaminant at many sites) it ranges from 3 mg L–1 (Younger, 2000) to more than 200 mg L–1 (Marsden et al., 1997). Aerobic wetlands are also being increasingly utilized in the final ‘polishing process’ in conventional alkali‐dosing systems (Parker, 2000), where they may receive pre‐treated waters containing only 1–2 mg L–1 Fe.

The ability of wetland plants to flourish in environments with high Fe concentrations has been attributed to the oxidation of soluble ferrous iron to insoluble ferric iron in the rhizosphere (Bartlett, 1961). The formation of iron oxyhydroxide deposits on the roots of wetland plants may reduce the amount of iron entering the plant tissues and thus provide a mechanism for the avoidance of toxicity. However, such iron oxide deposits may in turn adsorb nutrients such as phosphate, reducing their uptake into plant tissues and potentially resulting in nutrient deficiency. Indeed, in studies of rice cultivars growing in areas of high iron concentration, poor growth has been attributed to nutrient deficiency rather than iron toxicity (Howeler, 1973; Ottow et al., 1983; Yamauchi, 1989). In some recent experiences of wetland treatment systems, the growth rates of reeds, which originally appeared to thrive in the first growing season after commissioning, have abruptly declined in the second growing season (D. Phillipps, pers. comm.). This may be explained by the sorption of nutrients on the developing iron plaque deposits.

The main objectives of this study were: (a) to determine whether, and to what degree, the aqueous iron concentration in the growing medium affects the growth of, and Fe uptake by, the wetland species P. australis, and (b) whether the presence of iron in the growing environment affects the uptake of the essential element phosphate in the wetland species P. australis. The results have direct relevance to the development of guidelines for the management of wetlands designed to treat mine water.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Seeds of P. australis Trin. ex Steudel collected from an uncontaminated field site in Felixstowe, UK, in 1997 were fully imbibed and chilled at 4 °C in the dark for 2 weeks. The seeds were then transferred to a controlled environment growth chamber (8 h 14 °C night, 16 h 20 °C day, 250–300 µmol m–2 s–1 photon flux density). Once germination had occurred seedlings were grown, supported on polystyrene beads, for 17 d in 10 % Rorison’s nutrient solution (Hewitt, 1966). Seedlings of a uniform size were selected and one transplanted into each of 50 opaque PVC vessels (1 L capacity) containing 10 % Rorison’s solution (pH 6·0). This allowed for five replicates of all treatments and these were arranged in a randomized block design. The seedlings were grown for a further 27 d with the nutrient solution being changed every 3 d to maintain nutrient supply and compensate for any chemical changes in the solution. At the end of this period, iron was added to the containers in the form of FeSO4·7H2O (+ standard nutrient solution without FeEDTA) in appropriate quantities to give the following treatments: 0, 0·05, 0·1, 0·5, 1·0, 2·0, 5·0, 10·0, 20·0 and 50·0 mg L–1 Fe. Phosphorus concentration in the nutrient solution was 0·31 mg L–1. The exposure to varying iron concentrations was continued for 64 d during which solutions were changed at intervals of 3 d.

Visual observations of plant condition were made at each solution change. Measurements of the longest root and shoot extension were made at intervals of 3 d. At the conclusion of the experiment all plants were harvested and rinsed thoroughly in distilled water to remove potential surface contaminants. Each plant was divided into roots, rhizomes and shoots and the individual components placed in labelled envelopes and dried at 40 °C for 3 d. The resulting material was placed in a desiccator and cooled to room temperature before being weighed. A sub‐sample of known weight (0·1–0·3 g) of dried material was then acid digested in 5 mL of 30 % HNO3 at 90 °C for a minimum of 8 h. The concentration of Fe in the digests was determined using an ATI Unicam 929 atomic absorption spectrophotometer. Phosphate was measured using the ascorbic acid method (American Public Health Association, 1995) modified for acid digests. One millilitre of digest was diluted to 50 mL with de‐ionized water, and the pH adjusted with 1 n NaOH and 5 n H2SO4. Absorbance was measured at 880 nm on a UNICAM 8625 spectrometer. Extraction efficiency was checked using BCR (hay powder).

Data on plant growth and concentrations of phosphate were analysed using a one‐way ANOVA followed by a Tukey‐HSD test. Where necessary, data transformations (either loge or log10) were carried out.

RESULTS

Visual appearance of seedlings

Before the imposition of experimental treatments, all seedlings showed similar growth and development of both roots and shoots. Following initiation of Fe treatments, a number of visual differences between the treatments became apparent. Seedlings supplied with 1 mg L–1 Fe and above developed a deep orange staining along the root length from 1 cm behind the root tip, indicating the formation of iron precipitates or ‘iron plaque’. The depth of colour was greater with increasing supply of iron.

Seedlings exposed to 2 mg L–1 Fe and above showed various changes in morphology including stunted shoot growth, browning and/or die‐back of leaves, brown patches on the leaves, stunted root growth, lack of branching of roots and root flaccidity. The severity of the changes was greatest in those seedlings exposed to 20 and 50 mg L–1 Fe, with complete die‐back of shoots in most replicates.

Seedlings exposed to concentrations of less than 0·5 mg L–1 continued to develop normally after Fe treatment was begun with the exception of some yellowing of the leaves. Those seedlings supplied with 0·5 and 1·0 mg L–1 showed no adverse effects.

Effect of Fe supply on seedling growth

In seedlings exposed to 0·5 mg L–1 and below, the rate of root growth (measured as mm d–1) was increased considerably after Fe treatment was initiated (Fig. 1). Those seedlings exposed to 1 mg L–1 Fe showed a gradual increase in root growth after the start of Fe treatments, whereas those subjected to more than 2 mg L–1 Fe showed an immediate decrease in the rate of root growth. All seedlings showed a decline in the rate of growth after the tenth measurement.

Fig. 1. Growth rates of Phragmites australis seedlings exposed to different concentrations of Fe.

Root lengths were significantly greater (P < 0·001) in seedlings exposed to less than 2 mg L–1 Fe than to 2 mg L–1 and above (Table 1). This pattern was also reflected in the shoot : root ratio where seedlings exposed to more than 2 mg L–1 had a lower ratio value than those below (P < 0·001). In addition, seedlings grown in 0 mg L–1 Fe showed a lower shoot : root ratio than those in 0·5 mg L–1 Fe.

Table 1.

Biomass and growth of Phragmites australis seedlings exposed to different concentrations of Fe (mean value ± s.e., n = 5)

| Fe supply concentration (mg L–1) | Dry weight of root (g plant–1) | Dry weight of rhizome (g plant–1) | Dry weight of shoot (g plant–1) | Root length (cm) | Shoot: root ratio |

| 0 | 1·5 ± 0·13a | 0·5 ± 0·08a | 1·5 ± 0·18a | 8·2 ± 0·62a | 1·1 ± 0·13a |

| 0·05 | 1·6 ± 0·21a | 0·4 ± 0·08abc | 1·4 ± 0·09a | 8·6 ± 0·40a | 1·2 ± 0·19ab |

| 0·1 | 2·0 ± 0·16a | 0·5 ± 0·10a | 1·5 ± 0·15a | 8·3 ± 0·18a | 1·4 ± 0·03ab |

| 0·5 | 1·6 ± 0·06a | 0·5 ± 0·08a | 1·1 ± 0·12ab | 9·0 ± 0·62a | 1·6 ± 0·16b |

| 1·0 | 1·6 ± 0·09a | 0·4 ± 0·09ab | 1·3 ± 0·10a | 7·7 ± 0·69a | 1·2 ± 0·08ab |

| 2·0 | 0·3 ± 0·09b | 0·2 ± 0·04abcd | 0·6 ± 0·13bc | 2·8 ± 0·51b | 0·6 ± 0·07c |

| 5·0 | 0·2 ± 0·07b | 0·2 ± 0·07abc | 0·4 ± 0·10c | 2·7 ± 0·42b | 0·5 ± 0·07c |

| 10·0 | 0·08 ± 0·018b | 0·1 ± 0·03bcd | 0·3 ± 0·03c | 2·0 ± 0·19b | 0·3 ± 0·08c |

| 20·0 | 0·04 ± 0·007b | 0·05 ± 0·017d | 0·2 ± 0·03c | 2·0 ± 0·28b | 0·2 ± 0·04c |

| 50·0 | 0·07 ± 0·020b | 0·08 ± 0·032cd | 0·3 ± 0·07c | 2·5 ± 0·20b | 0·2 ± 0·02c |

Different superscript letters in a column indicate a significant difference at P = 0·05, according to the Tukey‐HSD test.

Dry weights of seedlings (Table 1) were also significantly affected by Fe solution concentration (root, P < 0·001; rhizome, P < 0·001; shoot, P < 0·01). Seedlings grown in concentrations of 5 mg L–1 and above had a lower shoot dry weight than those in 1 mg L–1 and below. This was also true for root dry weights, with the exception of those grown in 2 mg L–1 Fe, which yielded weights that were significantly lower than those for seedlings grown in 1 mg L–1 and below. The effect of Fe concentration on rhizome dry weight was less clear, but plants grown in 20 and 50 mg L–1 Fe had significantly lower dry weights than those grown in less than 2 mg L–1.

Effects of Fe concentration on Fe uptake

It is evident from Table 2 that Fe concentrations were highly variable in the majority of cases. This is most likely to be due to variation in Fe distribution within and adsorbed by plant tissues, and it was particularly evident in the root samples. Distribution of iron deposits upon roots is known to be patchy in nature (e.g. Batty et al., 2000) and therefore results gained from digestion of roots are likely to be highly variable. This inherent variability must be considered in the interpretation of results, but major differences between treatments can be identified using rigorous statistical analyses.

Table 2.

Concentration of Fe in roots, rhizomes and shoots of Phragmites australis seedlings exposed to different concentrations of Fe (mean value ± s.e., n = 5)

| Root | Rhizome | Shoot | |||||||

| Fe supply conc. (mg L–1) | Mean Fe concentration (mg kg–1 d. wt) | Low | High | Mean Fe concentration (mg kg–1 d. wt) | Low | High | Mean Fe concentration (mg kg–1 d. wt) | Low | High |

| 0 | 719 ± 297·8a | 50·5 | 1750 | 88·6 ± 50·58ab | BD | 139 | 21·9 ± 4·97a | BD | 31·8 |

| 0·05 | 568 ± 130·1a | 155 | 926 | 24·6 ± 11·68a | 4·25 | 67·8 | 36·1 ± 13·14a | 10·2 | 86·8 |

| 0·1 | 1327 ± 337·0a | 244 | 2174 | 151 ± 72·9ab | 21·6 | 279 | 65 ± 17·8a | 20·9 | 114 |

| 0·5 | 5465 ± 881·8a | 3428 | 8757 | 232 ± 54·8ab | 173 | 442 | 42 ± 11·2a | 10·4 | 67·7 |

| 1·0 | 14 608 ± 1948·5ab | 8851 | 18 070 | 642 ± 84·8ab | 430 | 846 | 125 ± 56·1a | 17·5 | 316 |

| 2·0 | 51 231 ± 2767·7c | 46 734 | 61 991 | 4197 ± 1026·5ab | 1125 | 7497 | 97 ± 37·5a | 22·1 | 240 |

| 5·0 | 41 346 ± 5170·5bc | 30 482 | 56 176 | 6940 ± 2149·1ab | 921 | 10 415 | 144 ± 34·4a | 39 | 253 |

| 10·0 | 59 096 ± 11 416·1c | 42 582 | 100 930 | 13 174 ± 3016·3ab | 8612 | 24 691 | 216 ± 72·8a | 94 | 399 |

| 20·0 | 51 072 ± 3412·7c | 42 202 | 55 691 | 21 818 ± 2586·5ab | 17 170 | 26 582 | 477 ± 162·6ab | 42 | 871 |

| 50·0 | 76 913 ± 13 368·4c | 50 617 | 125 520 | 51 846 ± 26 969·7b | 16 310 | 159 174 | 729 ± 211·1b | 286 | 1501 |

Different superscript letters in a column indicate a significant difference at P = 0·05 according to the Tukey‐HSD test.

BD = below detection.

There was a significant effect of external concentration on root (P < 0·001), rhizome (P < 0·001) and shoot (P < 0·001) Fe concentration. Shoot Fe content was significantly greater in seedlings exposed to 50 mg L–1 Fe. The highest mean shoot content (n = 5) was 729 mg kg–1 dry weight (Table 2). Seedlings exposed to 2 mg L–1 Fe or more had significantly greater root Fe content than those exposed to 0·5 mg L–1 or less. The highest mean (n = 5) Fe content (76913 mg kg–1 d. wt) was found in those seedlings grown in 50 mg L–1 Fe and the lowest (568 mg kg–1 d. wt) in those grown in 0·05 mg L–1 Fe. There were few significant differences between Fe contents of rhizomal material, with the exception that there was a lower rhizomal Fe content in seedlings grown in 0·05 mg L–1 Fe than in 50 mg L–1 Fe.

Effect of Fe supply on phosphate uptake

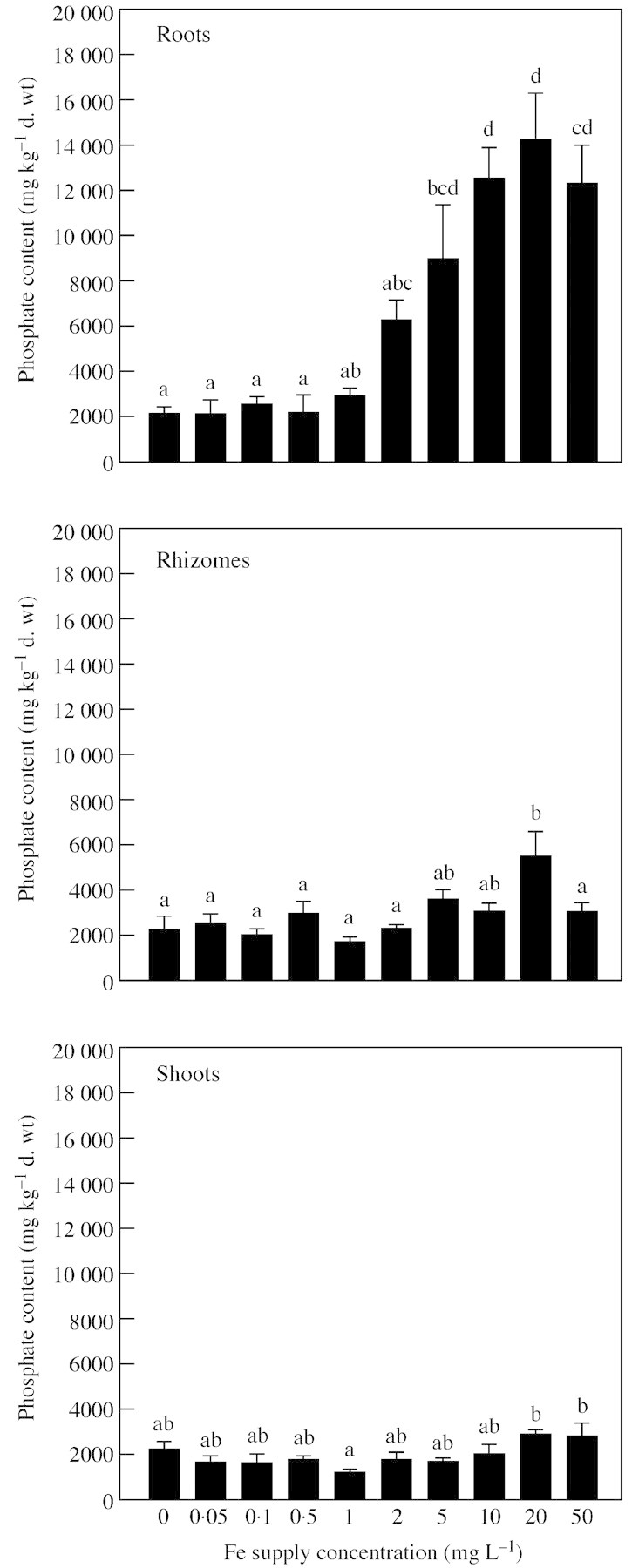

There was a significant effect of external Fe concentration on root (P < 0·001), rhizome (P < 0·005) and shoot (P < 0·05) phosphate concentrations in tissues. Phosphate content of roots was lower in seedlings exposed to less than 1 mg L–1 Fe when compared with those exposed to more than 1 mg L–1 Fe, although this was not statistically significant for those in 2 mg L–1 Fe (Fig. 2). Phosphate concentration of roots was consistently higher than those of shoots or rhizomes when seedlings were exposed to 2 mg L–1 Fe and above, reaching the highest level of 14200 mg kg–1 dry wt when grown in 20 mg L–1.

Fig. 2. Concentration of phosphate in roots, rhizomes and shoots of Phragmites australis seedlings exposed to different concentrations of Fe (root concentration includes external plaque deposits). Different letters indicate a significant difference at P = 0·05 according to the Tukey‐HSD test.

In rhizomal material there were few significant differences in phosphate content among the different Fe solution concentrations. Phosphate content was, however, significantly greater in seedlings exposed to 20 mg L–1 Fe than to 0–2 and 50 mg L–1.

The lowest phosphate content of shoots was found in seedlings growing in 1 mg L–1 Fe, and this was significantly lower than those growing in 20 and 50 mg L–1. No significant difference in phosphate content of shoots was found between the remaining treatments.

DISCUSSION

The growth rates and cycles of macrophytes in constructed wetlands designed to treat metal‐contaminated mine water can be very variable, but the reasons for this are unclear. The chemical characteristics of the range of waters treated by these systems vary greatly and one of the main sources of variation is in the concentration of metals. Iron constitutes the main contaminant in most mine water discharges (e.g. Hedin et al., 1994; Banks et al., 1997) and this could be an important factor in controlling the performance of the macrophytes used. This investigation examined the effects of a range of iron concentrations on the growth of the common reed P. australis, and these were related to the uptake of Fe and phosphate into plant tissues and deposits associated with roots.

It was evident from the data that there was a threshold Fe concentration above which the growth of P. australis seedlings was severely inhibited. When Fe was supplied at a concentration above 1 mg L–1, root length, dry weight of roots and, to a lesser extent, dry weight of shoots were significantly reduced (Table 1). In addition, at these higher Fe solution concentrations plants exhibited visual symptoms of possible iron toxicity, including root flaccidity, reduced root branching, increased shoot die‐back and mottling of leaves. These symptoms were particularly evident when Fe was supplied at concentrations above 10 mg L–1. Previous investigations of wetland species including P. australis, have shown visible effects of high Fe concentrations similar to those found here (Snowden and Wheeler, 1993, 1995).

Root growth measurement in mm d–1 confirmed the inhibitory effect of elevated concentrations of Fe. Upon initiation of Fe treatments, the growth of roots was noticeably reduced in seedlings grown in 2 mg L–1 and above, falling to 0 mm d–1 for those grown in 10 mg L–1 and above. Seedlings exposed to less than 1 mg L–1 Fe actually showed stimulation of root growth upon initiation of Fe treatment. These seedlings suffered a reduction in Fe supply and therefore the plants may have reallocated resources to increase root growth in an attempt to locate new sources of this essential nutrient. Those seedlings grown in 1 mg L–1 did not show a substantial increase in root growth following initiation of Fe treatment, but rather a gradual increase before reaching a peak by the tenth measurement. As the Fe supply in this case was approximately at the optimum concentration for normal seedling development, neither root growth inhibition nor stimulation resulted.

The inhibition of growth with increasing Fe supply can perhaps be explained by one or both of two major causes: (1) elevated concentrations of Fe result in iron toxicity within the plants; and (2) high Fe concentrations impede the uptake of nutrients by the plants, thus resulting in nutrient deficiency.

Visible signs of the presence of iron oxyhydroxide plaque deposits on the roots of the seedlings were found when Fe was supplied at a concentration of 1 mg L–1 and above.

The depth of orange colour on the roots increased with increasing Fe supply. It has been suggested previously that these deposits could adsorb essential elements including phosphate and thus immobilize them, preventing their uptake by the plant (Christensen and Sand‐Jensen, 1998). This could then result in deficiencies of nutrients and corresponding reductions in seedling growth.

Both Fe toxicity (for monocotyledons) and nutrient deficiency have been invoked previously to explain a decrease in the shoot : root ratio (Marschner, 1995; Snowden and Wheeler, 1995), and similar decreases were evident in the seedlings grown in higher Fe concentrations in the present study.

The data presented here showed that Fe uptake by plants did increase with increasing Fe supply but there was not a clear relationship in all cases. In shoot tissues, iron content did not increase significantly until Fe was supplied at a concentration greater than 10 mg L–1 (albeit there was some statistically non‐significant increase above 5 mg L–1). It must be noted here that variability in Fe concentration in shoot tissues was extremely high, particularly when Fe was supplied at high concentrations. The extraction technique used was tested using standard reference materials and was eliminated as a potential cause for analytical problems. It is thought that the variability is due to the use of subsamples of plant material. Fe would not have been evenly distributed throughout plant tissues but concentrated in certain areas, and subsampling of material could have increased such variability in distribution. The use of replicates and statistical techniques, however, still enables differences between treatments to be identified.

The increase in iron content evidently was not related to the inhibition of growth that occurred when Fe was supplied at a concentration greater than 1 mg L–1. The Fe content in shoot tissues at which toxicity is reached varies with each species, but is approx. 1100–1600 mg kg–1 d. wt of leaf tissues for most wetland plants (Marschner, 1995). In none of the seedlings in the present study was this threshold attained. It is possible that the threshold may be lower in young plants, as it has previously been demonstrated that less Fe is required to injure seedlings (5 d old) than mature plants (95 d old) (Foy et al., 1978). The seedlings in the present study were 42 d old when Fe treatment was started and, therefore, it is conceivable that the toxicity threshold could have been lower. However, Fe content of shoots was similar for seedlings grown in 1 mg L–1 , which showed no inhibition of growth, and those grown in 2 and 5 mg L–1 Fe, which showed definite inhibition. It may be possible that, at concentrations of 20 and 50 mg L–1, the internal shoot concentration that was reached was at a critical toxicity level (lower than that previously proposed by Marschner, 1995) resulting in reduced growth of the seedlings. The reduction in growth of seedlings at 2 and 5 mg L–1 may not be due to direct toxicity, but to another mechanism.

Studies of rice cultivars have previously suggested that the inhibition of plant growth and severity of bronzing shown in plants growing in high Fe environments may be related to nutrient deficiency rather than to Fe toxicity (Howeler, 1973; Yamauchi, 1989). Ottow et al. (1983) found that, in studies of rice cultivars from sites toxic in Fe, the plants had P, K and Zn deficiencies in their leaves. In addition, studies on wetland plant species demonstrated that shoot P concentration decreased with increasing external Fe supply (Snowden and Wheeler, 1995). Iron hydroxides have high specific surface areas and are thus able to adsorb cations and anions including phosphate (Kuo, 1986). The presence of iron oxide deposits on the roots of wetland plants could thus act as a filter for nutrients such as phosphate, thereby causing deficiency in the aerial parts of the plant. Zhang et al. (1999) found that the amount of P adsorbed by iron oxide plaque increased with the amount of plaque present on the roots. Examination of the results from the current study showed that, at and above 1 mg L–1 external Fe supply, the roots were characterized by a deep orange colour that extended from 1 cm behind the tip along the length of the root. This reflects the presence of an iron oxide plaque. Phosphate concentrations in the same roots also showed an increase when external Fe supply was above 1 mg L–1 (although this was statistically significant only above 2 mg L–1). This suggests that phosphate was associated with the Fe, most likely as a deposit on the root surface. However, phosphate concentrations in shoot tissues of the same plants showed a different pattern. Despite the apparent immobilization of phosphate at the root surface there were few significant differences in shoot concentrations among the treatments. In fact, phosphate concentration seemed to be greater at the highest external Fe supplies (20 and 50 mg L–1), although this was not statistically significant. It must be noted here that, at an external Fe supply of 50 mg L–1, the seedlings showed complete die‐back of shoots and they were effectively dead. However, the die‐back of shoots was a gradual process and the seedlings continued to function for a number of days after initiation of metal treatments, during which time Fe and phosphate uptake would have continued.

It appears that adsorption of phosphate by iron plaque, although constituting an important process, did not prevent the eventual uptake of phosphate into the aerial tissues in this particular experiment. It is possible that the main pathway by which nutrients are taken up by plants that form iron plaques is not through the root, but rather through submerged hydropotes of the above‐ground part of the aerial shoot (e.g. Luther, 1983). In the case studied here, although some phosphate was immobilized in the root plaque, uptake into plant tissues was still sufficient to prevent deficiency; this may have been achieved through this alternative pathway. In addition, since iron plaque does not cover the whole of the axis of the root, there may be a pathway of uptake around the root tip. However, it has been suggested that, under phosphorus deficiency, the basal zones become more important in P uptake (Marschner, 1995) than the root apex.

It has been suggested previously that iron oxide plaques may act as a nutrient reservoir in times of deficiency (e.g. Conlin and Crowder, 1989). Root exudates have been implicated in the subsequent desorption of phosphorous from the plaque surface, but Zhang et al. (1999) found that phytosiderophores did not affect phosphorous uptake. Other studies (Begg et al., 1994) have implied that acidification, resulting from the oxidation of Fe at the root surface, may help to solubilize nutrients with restricted availability. The increase in shoot phosphate concentration in the present study was negligible, however, and it appears that, although the plaque may store phosphate, this cannot be remobilized. If this remobilization of phosphate had been possible, it would be expected that shoots of seedlings growing in higher external Fe supply would contain a significantly higher phosphate content. The phosphate content in all shoots was approx. 0·2–0·3 % of the total shoot biomass, a level that is sufficient for adequate growth. It may be the case that the store of phosphate in the plaque can be utilized only in times of nutrient deficiency.

The cause of the growth inhibition in seedlings exposed to more than 1 mg L–1 Fe, therefore, remains unclear. Phosphate is not the only nutrient to be implicated in the exacerbation of bronzing in rice cultivars, and it has been suggested that Mg, K, Ca and Zn deficiencies may also be involved (Howeler, 1973; Ottow et al., 1983; Benckiser et al., 1984; Yamauchi, 1989). All of these metals are known to be adsorbed by ferric hydroxide (e.g. Kuo, 1986; Dzombah and Morel, 1990). Further investigations are therefore needed to determine whether deficiency in these nutrients may be involved in the reduction of P. australis growth rate in the presence of high concentrations of soluble Fe.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr A. Borland, Department of Agricultural and Biological Sciences, University of Newcastle for the use of controlled growth facilities. The study was completed as part of PIRAMID (Passive In‐situ Remediation of Acidic Mine/Industrial Drainage), a research project of the European Commission Fifth Framework Programme (Key Action 1: Sustainable Management and Quality of Water) Contract no. EVK1‐CT‐1999‐000021).

Supplementary Material

Received: 13 June 2003; Returned for revision: 8 August 2003; Accepted: 2 September 2003 Published electronically: 17 October 2003

References

- American Public Health Association.1995.Standard methods for the examination of wastewater, 19th edn. New York, USA: American Public Health Association Inc. [Google Scholar]

- BanksD, Younger PL, Arnesen RT, Iversen ER, Banks SB.1997. Mine water chemistry: the good, the bad and the ugly. Environmental Geology 32: 157–174. [Google Scholar]

- BartlettRJ.1961. Iron oxidation proximate to plant roots. Soil Science 92: 372–379. [Google Scholar]

- BattyLC, Baker AJM, Wheeler BD, Curtis CD.2000. The effect of pH and plaque on the uptake of Cu and Mn in Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin ex. Steudel. Annals of Botany 86: 647–653. [Google Scholar]

- BeggCBM, Kirk GJD, Mackenzie AF, Neue HU.1994. Root‐induced iron oxidation and pH changes in the lowland rice rhizosphere. New Phytologist 128: 469–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BenckiserG, Santiago S, Neue HU, Watanabe I, Ottow JCG.1984. The mechanism of excessive iron‐uptake (iron toxicity) of wetland rice. Journal of Plant Nutrition 7: 177–185. [Google Scholar]

- ChristensenKK, Sand‐Jensen K.1998. Precipitated iron and manganese plaques restrict root uptake of phosphorus in Lobelia dortmanna Canadian Journal of Botany 76: 2158–2163. [Google Scholar]

- ConlinTSS, Crowder AA.1989. Location of radial oxygen loss and zones of potential iron uptake in a grass and two nongrass emergent species. Canadian Journal of Botany 67: 717–722. [Google Scholar]

- DzombahDA, Morel, FMM.1990.Surface complexation modelling: hydrous ferric oxide. New York, USA: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- FoyCD, Chaney RL, White MC.1978. The physiology of metal toxicity in plants. Annual Review of Plant Physiology 29: 511–566. [Google Scholar]

- HaslamSM.1972. Biological flora of the British Isles: Phragmites communis Trin. Journal of Ecology 60: 585–610. [Google Scholar]

- HedinRS, Nairn RW, Kleinmann RLP.1994.Passive treatment of coal mine drainage. US Dept of the Interior, Bureau of Mines Information Circular No. 9389. [Google Scholar]

- HewittEJ.1966.Sand and water culture methods used in the study of plant nutrition. Technical Communication No. 22, Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux, Farnham Royal, Bucks. [Google Scholar]

- HowelerRH.1973. Iron induced oranging disease of rice in relation to physico‐chemical changes in a flooded oxisol. Soil Science Society of America Proceedings 37: 898–903. [Google Scholar]

- KuoS.1986. Concurrent sorption of phosphate and zinc, cadmium, or calcium by a hydrous ferric oxide. Soil Science Society of America Journal 50: 1412–1419. [Google Scholar]

- LambHM, Dodds‐Smith M, Gusek J.1998. Development of a long‐term strategy for the treatment of acid mine drainage at Wheal Jane. In: Geller W, Klapper H, Salomons W, eds. Acidic mining lakes. Acid mine drainage, limnology and reclamation Heidelberg: Springer, 335–346. [Google Scholar]

- LutherH.1983. On life forms and aboveground and underground biomass of aquatic macrophytes. Acta Botanica Fennica 123: 1–23 [Google Scholar]

- MarschnerH.1995.Mineral nutrition of higher plants, 2nd edn. London: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- MarsdenM, Kerr K, Holloway D, Wilbraham D.1997. The position in Scotland. In: Bord L, ed. Proceedings of the UK Environment Agency Conference on Abandoned Mines: Problems and Solutions, Leeds: Environment Agency, 74–84. [Google Scholar]

- OttowJCG, Benckiser G, Watanabe I, Santiago S.1983. Multiple nutritional soil stress as the prerequisite for iron toxicity of wetland rice (Oryza sativa L.). Tropical Agriculture (Trinidad) 60: 102–106 [Google Scholar]

- ParkerK.2000. Mine water‐the role of the Coal Authority. Transactions of the Institute of Mining and Metallurgy (Section A: Mining Technology) 109: A219–A223. [Google Scholar]

- SchierupHH, Larsen VJ.1981. Macrophyte cycling of zinc, copper, lead and cadmium in the littoral zone of a polluted and non‐polluted lake. I. Availability, uptake and translocation of heavy metals in Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. Aquatic Botany 11: 197–210. [Google Scholar]

- ScholesL, Shutes RBE, Revitt DM, Forshaw M, Purchase D.1998. The treatment of metals in urban runoff by constructed wetlands. Science of the Total Environment 214: 211–219. [Google Scholar]

- SnowdenRED, Wheeler BD.1993. Iron toxicity to fen plant species. Journal of Ecology 81: 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- SnowdenRED, Wheeler BD.1995. Chemical changes in selected wetland plant species with increasing Fe supply, with specific reference to root precipitates and Fe tolerance. New Phytologist 131: 503–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der WerffM.1991. Common reed. In: Rozema J, Verkleij JAC. Ecological responses to environmental stress. Dordecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 172–182. [Google Scholar]

- YamauchiM.1989. Rice bronzing in Nigeria caused by nutrient imbalances and its control by potassium sulfate application. Plant and Soil 117: 275–286. [Google Scholar]

- YoungerPL.2000. The adoption and adaptation of passive treatment technologies for mine waters in the United Kingdom. Mine Water Environment 19: 84–97. [Google Scholar]

- YoungerPL, Banwart SA, Hedin RS.2002.Mine water: hydrology, pollution, remediation. Dordecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- ZhangX, Zhang F, Mao D.1999. Effect of iron plaque outside roots on nutrient uptake by rice (Oryza sativa L.). Phosphorus uptake. Plant and Soil 209: 187–192. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.