Abstract

Cocoa breeders and growers continue to face the problem of high heterogeneity between individuals derived from one progeny. Vegetative propagation by somatic embryogenesis could be a way to increase genetic gains in the field. Somatic embryogenesis in cocoa is difficult and this species is considered as recalcitrant. This study was conducted to investigate the phenolic composition of cocoa flowers (the explants used to achieve somatic embryogenesis) and how it changes during the process, by means of histochemistry and conventional chemical techniques. In flowers, all parts contained polyphenolics but their locations were specific to the organ considered. After placing floral explants in vitro, the polyphenolic content was qualitatively modified and maintained in the calli throughout the culture process. Among the new polyphenolics, the three most abundant were isolated and characterized by 1H‐ and 13C‐NMR. They were hydroxycinnamic acid amides: N‐trans‐caffeoyl‐l‐DOPA or clovamide, N‐trans‐p‐coumaroyl‐l‐tyrosine or deoxiclovamide, and N‐trans‐caffeoyl‐l‐tyrosine. The same compounds were found also in fresh, unfermented cocoa beans. The synthesis kinetics for these compounds in calli, under different somatic embryogenesis conditions, revealed a higher concentration under non‐embryogenic conditions. Given the antioxidant nature of these compounds, they could reflect the stress status of the tissues.

Key words: Theobroma cacao L., somatic embryogenesis, histochemistry, hydroxycinnamic acid amides, N‐trans‐p‐coumaroyl‐l‐tyrosine, deoxiclovamide, N‐trans‐caffeoyl‐l‐tyrosine, N‐trans‐caffeoyl‐l‐DOPA, clovamide, recalcitrance

INTRODUCTION

Cocoa provides a substantial income for smallholders in the Tropics. Cocoa breeders continue to face the problem of high heterogeneity between individuals derived from one cross, and heterogeneous transmission of genetic traits to the progeny. In this context, the use of somatic embryogenesis, a generally efficient micropropagation technique to multiply elite material, would constitute an important step. A few papers report cocoa somatic embryogenesis from floral parts (Lopez‐Baez et al., 1993; Alemanno et al., 1996, 1997; Li et al., 1998). It is now possible to produce plantlets from numerous genotypes (Li et al., 1998). However, cocoa remains a generally recalcitrant species, and the results are inadequate for commercial production of elite material. Recalcitrance is defined as the inability of plant cells, tissues and organs to respond readily to tissue culture (Benson, 2000). One of the factors often considered as a component of in vitro recalcitrance is a high phenolic content and oxidation of these compounds. Naturally, cocoa contains large amounts of polyphenolics (Griffiths, 1958; Kim and Keeney, 1983). Their oxidation could be a limiting factor preventing proper tissue multiplication and maintenance. The objectives of the reported work were to investigate, by histochemical means, the composition and location of phenolic compounds in cocoa flowers, and their evolution throughout the somatic embryogenesis process. This paper reports on the qualitative study of this chemical change, focusing on the isolation and characterization of three hydroxycinnamic acid amides never before identified in cocoa callus cultures. Embryogenic and non‐embryogenic situations were also compared.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant material and in vitro culture

Two genotypes, belonging to two cocoa tree groups, were used: NA 79 (Forastero) and R 106 (Criollo). Flower buds (6–8 mm long) from Theobroma cacao L. were collected from trees grown in the glasshouse and surface‐sterilized for 20 min in a 10 % sodium hypochlorite solution. After dissecting the buds, the staminodes and anthers were cultured on a callogenesis medium (CM) consisting of Murashige and Skoog’s medium (Murashige and Skoog, 1962) supplemented with glycine (3 mg l–1), lysine (0·4 mg l–1), leucine (0·4 mg l–1), arginine (0·4 mg l–1), tryptophan (0·2 mg l–1), 2,4‐dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2 mg l–1), kinetin (0·25 mg l–1), coconut water (50 ml l–1) and sucrose (40 g l–1) as described previously (Lopez‐Baez et al., 1993). After 3 weeks on CM medium, the tissues were transferred onto a hormone‐free expression medium (EM), supplemented with glycine (1 mg l–1), lysine (0·2 mg l–1), leucine (0·2 mg l–1), arginine (0·2 mg l–1), tryptophan (0·1 mg l–1), coconut water (100 ml l–1) and sucrose (40 g l–1). On this medium, somatic embryos regenerated from the calli.

Histochemistry

Histochemical localization of polyphenolics was carried out on fresh flower buds and calli derived from staminodes/anthers (7, 21 and 42 d after culture initiation) of NA 79 (Forastero) and R 106 (Criollo) genotypes. After adding the material to an 8 % agar solution, 50‐µm‐thick sections were cut with a vibration microtome (Micro‐cut H1200; Bio‐rad; frequency 4 and speed 4). Fresh sections were immediately mounted on microscope slides with different chemicals depending on the phenolic compound being sought. Naturally coloured anthocyanins were directly observed with a photonic microscope in visible light on sections mounted in 15 % glycerine water. For red‐staining tannins, sections were placed for a few minutes in chlorhydric vanillin and mounted in a drop of this reagent (Dai et al., 1995). Observations were made in visible light. For hydroxycinnamic derivatives, sections were placed for a few minutes in Neu’s reagent [1 % 2‐aminoethyl diphenyl borinate (Fluka, Chemie AG, Buchs, Switzerland) in absolute methanol] and mounted in 15 % glycerine water (Dai et al., 1995). Observations were carried out using a light microscope (Nikon Optiphot) with two filter sets: a UV filter set with 365 nm excitation and a 400 nm barrier filter, and a blue filter with 420 nm excitation and a 515–560 nm barrier filter. Several sections were used with five replicates for each treatment.

Extraction of polyphenolics

Extraction was identical for both qualitative and quantitative studies. Twenty milligrams of freeze‐dried material were ground in liquid N2 and extracted with 15 ml MeOH–H2O (8 : 2) for 15 min at 4 °C with stirring. The extract was centrifuged for 10 min at 4 °C and 2500 g. The supernatant was isolated and the same operation repeated twice more with the remaining pellet. Total extracts were dry concentrated and resuspended with 15 ml hot water, filtered and freeze‐dried. The lyophilizates were resuspended in 1 ml of pure MeOH and filtered through 0·45 µm Millipore filters.

Two‐dimensional thin layer chromatography

The concentrated extracts were separated on cellulose layers (Merck, ref. 5552 KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) by two‐dimensional thin layer chromatography (2D TLC), using BuOH‐HOAc‐H2O (4 : 1 : 2·2) (solvent I) in one direction then 2 % OHAc (solvent II) in the other.

Analytical HPLC

This was performed on a 250 mm × 4·6 mm Kromasil 5 µm C18 analytical column at 22 °C. A linear gradient from 20–65 % acetonitrile in H2O, pH 2·6 for 20 min was used. The flow rate was 1 ml min–1. Detection was at 330 nm.

Purification and isolation for NMR studies

This was done with an XAD 761 Amberlite column resin (50 cm × 2 cm) which is an absorbant duolite. The fractions containing the hydroxycinnamic acid amides were eluted in water and then purified on a Sephadex LH 20 column (50 cm × 2 cm) with water as the elution solvent. Final purification of the three hydroxycinnamic acid amides was performed with semi‐preparative HPLC on a 250 mm × 10 mm Kromasil 10 µm C18 analytical column at 22 °C. A linear gradient from 30–48 % MeOH in H2O and a flow rate of 20 ml min–1 was used.

NMR studies

NMR spectra were measured at 360·13 MHz for 1H‐NMR and for 90·53 MHz for 13C‐NMR (Brucker AMX 360 apparatus). Chemicals were dissolved in DMSO‐d6 and the chemical shifts were given on the parts per million scale with TMS as the internal standard. The location of 1H and 13C was determined using COSY (correlation spectroscopy) two‐dimensional experiments, NOESY (nuclear overhauser effect spectroscopy), HMQC (heteronuclear multi‐quanta correlation) and HMBC (heteronuclear multi‐bond correlation).

Biochemical measurements

Total phenolics were measured with Folin‐Ciocalteu reagent (Dai et al., 1994). Twenty‐five microlitres of the extracts were mixed with 110 µL Folin‐Ciocalteu reagent, 200 µL 20 % sodium carbonate and 1·9 ml distilled water, and placed at 60 °C for 30 min. Optical density was measured with a spectrophotometer at 750 nm. A standard curve was established beforehand with chlorogenic acid.

Condensed tannins were measured with DMCA (Dai et al., 1995). Ten microlitres of extract were mixed with 200 µL DMCA reagent (100 mg DMCA + 10 mL 12 n hydrochloric acid + 90 mL methanol) and 1 mL methanol. Optical density was measured with a spectrophotometer at 640 nm, after 10 min at room temperature. A standard curve was established beforehand with (–)‐epicatechin. Three hydroxycinnamic derivatives were analysed by HPLC as previously described (Analytical HPLC). For determination of peak surfaces, three standard curves were established beforehand. Two measurements were taken per replicate.

Measurements of total phenolics, condensed tannins, and the three hydroxycinnamic derivatives were taken on three extract replicates for each treatment (genotype and 2,4‐D concentrations). Measurements were taken on days 0, 21, 32 and 42 of the somatic embryogenesis process. The data sets were processed by the Newmann–Keuls test, at the 5 % level.

RESULTS

Histo‐localization of polyphenolics

In cocoa flowers.

The cocoa flower has five free sepals, five free petals, five staminodes, five stamens (Fig. 1A) and an ovary of five united carpels. The petals comprise two distinct parts: a flat yellow ligule and a cup‐shaped white and purple pouch. Several polyphenolics were found in cocoa flowers. Hydroxycinnamic acids and flavonoids were revealed under UV and blue light with Neu’s reagent reactive; tannins were revealed under white light with chlorhydric vanillin; and anthocyanins were naturally stained red. All floral parts contained polyphenolics but their location and grouping were specific to the organ studied (Table 1; Fig. 1B–M). Generally, hydroxycinnamic acids were located in the epidermis of sporophytic organs: sepals (Fig. 1B), petals (Fig. 1C, F and G), staminodes and stamen filaments (Fig. 1I). In the ovary, these compounds were present in all tissues except the epidermis (Fig. 1L). Tannins were often present in all tissues, both epidermal and parenchymal (Fig. 1E, H and K). Anthocyanins were present in the epidermis and parenchyma of specific parts of the petals (Fig. 1D) and staminodes (Fig. 1J). No difference was detected between the two genotypes NA 79 (embryogenic) and R 106 (non‐embryogenic).

Fig. 1. Localization of phenolics in cocoa flowers. A, A cocoa flower. Bar = 0·3 cm. B, Cross‐section of a sepal treated with Neu’s reagent and observed under UV light, showing epidermal hair rich in flavonoids (yellow fluorescence) and hydroxycinnamic acids (blue‐white fluorescence). Bar = 96 µm. C, Cross‐section of cup‐shaped petal pouch treated with Neu’s reagent and observed under UV light. Hydroxycinnamic acids were present only in the epidermis. Bar = 42 µm. D, Naturally occurring anthocyanins in cup‐shaped petal pouch. Bar = 60 µm. E, Presence of tannins (revealed by chlorhydric vanillin and observed under white light) in the epidermis and in the rib of the cup‐shaped petal pouch. Bar = 96 µm. F, Cross‐section of petal ligule. Hydroxycinnamic acids were present only in the epidermis including stomata illustrated in G. Bar = 15 µm. H, Tannins were present in all cells of a cross‐section of the petal ligule. Bar = 84 µm. I, Hydroxycinnamic acids were present only in staminodes epidermis and anther filaments. Bar = 96 µm. J, Anthocyanins were present in staminodes rib cells. Bar = 96 µm. K, Tannins were present in all staminode cell types. Bar = 96 µm. L, Hydroxycinnamic acids were absent from the ovary epidermis but were present in parenchyma cells and inside the ovules. Bar = 120 µm. M, Cross‐section of the ovary showing tannins mainly present in the epidermis and in some parenchyma cells. Bar = 120 µm.

Table 1.

Location of different classes of polyphenolics in cocoa flowers

| Hydroxycinnamic acids | Flavonoids | Anthocyanins | Tannins | |

| Sepal | Epidermis (Fig. 1B) | Epidermal hair (Fig. 1B) | Epidermis and parenchyma | |

| Petal | ||||

| Ligule | Epidermis (Fig. 1F and G) | Sub‐epidermis and parenchyma | Parenchyma (Fig. 1H) | |

| Pouch | Epidermis (Fig. 1C) | Ornamental parenchyma (Fig. 1D) | Epidermis and parenchyma (Fig. 1E) | |

| Staminode | Epidermis (Fig. 1I) | Epidermis | Epidermis and parenchyma (Fig. 1J) | Epidermis and parenchyma (Fig. 1K) |

| Anther filament | Epidermis (Fig. 1I) | Epidermis and parenchyma | ||

| Ovary | All ovary tissues except epidermis | Epidermis (Fig. 1M) | ||

| Ovules (Fig. 1L) |

In staminodes, during the somatic embryogenesis process.

At culture initiation, hydroxycinnamic derivatives were located only in the epidermis of staminodes (Fig. 1I). Seven days after culture initiation, most parenchyma cells of the staminodes contained hydroxycinnamic derivatives, which were probably different from those present at culture initiation (Fig. 2A). Tannins and anthocyanins tended to disappear. At day 21, the embryogenic genotype NA 79 consisted of meristematic nodules (Alemanno et al., 1996) containing hydroxycinnamic derivatives (Fig. 2B). Tannins were exclusively located in cells situated around the meristematic nodules (Fig. 2C). In the second phase of the culture, the same observations were made. When somatic embryos regenerated, they were free of tannins (Fig. 2D) and had very small amounts of hydroxycinnamic derivatives. For the non‐embryogenic genotype R 106 at day 21, calli were compact and non‐meristematic (Alemanno et al., 1996). Such structures contained hydroxycinnamic derivatives distributed in a uniform manner (Fig. 2E). The location of tannins differed from that in embryogenic callus, being distributed in a random manner all over the callus (Fig. 2F). Histo‐localization of tannins could be a marker to distinguish embryogenic from non‐embryogenic calli.

Fig. 2. Localization of phenolics in cocoa explants during somatic embryogenesis process. A, Accumulation of polyphenolics inside staminode cells 7 d after culture initiation, treated with Neu’s reagent. Bar = 60 µm. B, Nodular callus cells derived from staminodes of embryogenic genotype NA 79, 21 d after culture initiation contained hydroxycinnamic derivatives. Bar = 60 µm. C, In a nodular callus derived from staminodes of embryogenic genotype NA 79, 21 d after culture initiation tannins were located on the periphery of the nodule, around meristematic cells. Bar = 60 µm. D, A young globular NA 79 somatic embryo treated with chlorhydric vanillin contained no tannins. Bar = 30 µm. E, Distribution of hydroxycinnamic derivatives in a compact non‐embryogenic callus derived from staminodes of genotype R 106, 21 d after culture initiation. Bar = 60 µm. F, In a compact non‐embryogenic callus derived from staminodes of genotype R 106, 21 d after culture initiation tannins were distributed throughout the callus. Bar = 60 µm.

Biochemical characterization of some phenolic compounds, particularly hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives, found in staminodes/anthers and derived calli

Thin layer chromatography (TLC) studies.

Two‐dimensional TLC was performed on staminodes/anthers (Fig. 3A) and derived calli at day 21 (Fig. 3B). The polyphenolic profiles of these two explants were significantly different. The floral organs contained two anthocyanins as well as three phenolic acids or derivatives. These were not studied in detail, but their response to UV light and to a few spray reagents revealed their chemical nature (Table 2). The profiles were qualitatively identical whichever genotype was analysed. The 2D TLC callus profile was far more complex (Fig. 3B) than that of the original explants (Fig. 3A). Seven hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives were revealed, all differing from those contained in the floral explants. They were identified as phenolic acid derivatives (Table 3). There was no qualitative difference between the tannins present in floral explants and the derived calli (data not shown).

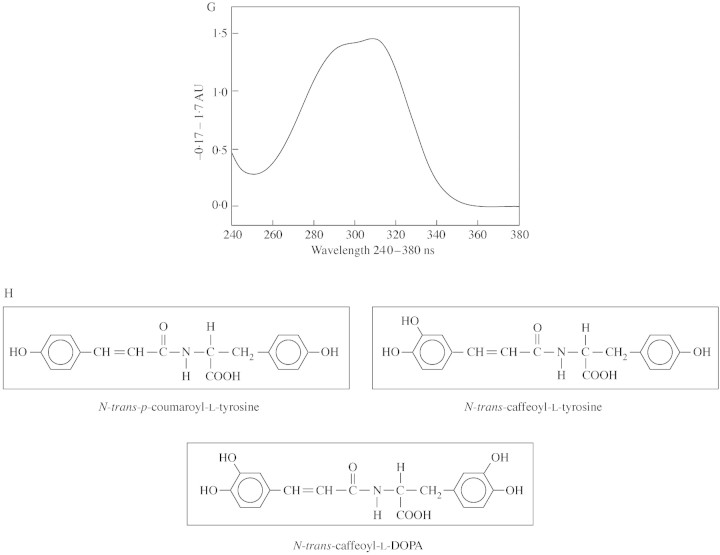

Fig. 3. Characterization of phenolics induced by in vitro culture conditions. A, 2D TLC of NA 79 staminodes with corresponding diagram showing anthocyanins (An) and hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives (A, A′, B and C). B, 2D TLC of NA 79 calli derived from staminodes/anthers 21 d after culture initiation with corresponding diagram showing seven hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives (1–1′, 2–2′, 3–3′, 4–4′, 5–5′, 6–6′ and 7). C and D, HPLC profiles of genotype NA 79 organs. E, UV spectra of peak 1. F, UV spectra of peak 2. G, UV spectra of peak 3. H, Chemical formulae of N‐trans‐p‐coumaroyl‐l‐tyrosine, N‐trans‐caffeoyl‐l‐tyrosine and N‐trans‐caffeoyl‐l‐DOPA.

Table 2.

Characteristics of phenolic compounds in staminodes/anthers separated by 2D TLC

| Spot | Observations | Conclusions |

| A–A′ | Fluorescence after spraying with Benedict’s reagent | Derivative of caffeic acid |

| Separation by an aqueous solvent: 2 % acetic acid | Isomers | |

| B | Non‐extinction of blue fluorescence after spraying with Benedict’s reagent | Hydroxycinnamic derivative |

| C | Non‐extinction of blue fluorescence after spraying with Benedict’s reagent | Sinapic or ferulic derivative |

Benedict’s reagent induces fluorescence of mono‐hydroxylated phenolics and extinction of fluorescence of di‐hydroxylated phenolics.

Table 3.

Characteristics of phenolic compounds in calli separated by 2D TLC

| Spots | Observations | Conclusions |

| 1–1′, 2–2′, 5–5′, 6–6′ | Extinction of fluorescence after spraying with Benedict’s reagent | Derivative of caffeic acid |

| Separation by an aqueous solvent: 2 % acetic acid | Isomers | |

| 3–3′ | Intensification of dark fluorescence under UV light after ammonia spraying | Derivative of para‐coumaric acid |

| Separation by an aqueous solvent: 2 % acetic acid | Isomers | |

| 4–4′ | Non‐extinction of fluorescence after spraying with Benedict’s reagent | Non‐derivative of caffeic acid |

| Separation by an aqueous solvent: 2 % acetic acid | Isomers | |

| 7 | Non‐extinction of fluorescence after spraying with Benedict’s reagent | Non‐derivative of caffeic acid |

Benedict’s reagent induces fluorescence of mono‐hydroxylated phenolics and extinction of fluorescence of di‐hydroxylated phenolics.

HPLC studies.

Hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives of staminodes/anthers and derived calli at day 21 were separated by HPLC (Fig. 3C). A comparison of both profiles confirmed the results obtained by 2D TLC. The two peaks, a and b, which may be minor caffeic acid derivatives, were common to both profiles. Five other peaks, c–g, were present only in calli. Of these, e–g were the most abundant and were more precisely identified. Correspondence between 2D TLC spots and HPLC peaks was established by elution of 2D TLC spots: 1–1′ = a; 2–2′ = b; 3–3′ = c. A comparison with fresh bean extracts showed clearly the presence of these three compounds in the beans (Fig. 3D).

Identification of three hydroxycinnamic amides.

UV spectra for these three compounds (Fig. 3E–G) were characteristic of hydroxycinnamic derivatives. Peaks 1 and 2 with respective maximum absorption (290 nm and 323 nm, Fig. 3E; 296 nm and 322 nm, Fig. 3F) were derivatives of caffeic acid, and peak 3 (292 nm and 310 nm, Fig. 3G) a derivative of p‐coumaric acid. These data confirmed the previous 2D TLC study. Alkaline hydrolysis experiments confirmed the presence of caffeic or p‐coumaric acid in these molecules. A second component of these molecules was identified as an amide or an amino acid.

Final identification was carried out using NMR studies (Table 4). Peak 1 was defined as N‐trans‐caffeoyl‐l‐DOPA, peak 2 as N‐trans‐caffeoyl‐l‐tyrosine and peak 3 as N‐trans‐p‐coumaroyl‐l‐tyrosine. These compounds differed in the degree of hydroxylation and could derive from one another (Fig. 3H).

Table 4.

1H‐ and 13C‐NMR spectrum of the compounds

| 1H | 1 | 2 | 3 | 13C | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Caffeic acid (1 and 2) | 1 | – | – | – | 1 | 126·2 | 126·1 | 125·9 |

| p‐Coumaric acid (3) | 2 | 6·97 (s)* | 6·93 (d; 2·0) | 7·37 (d; 8·2) | 2 | 114·1 | 113·6 | 129·1 |

| 3 | – | – | 6·77 (d; 8·2) | 3 | 145·9 | 145·3 | 115·6 | |

| 4 | – | – | – | 4 | 147·7 | 147·4 | 158·7 | |

| 5 | 6·70 (d; 8·0) | 6·73 (d; 8·0) | 6·77 (d; 8·2) | 5 | 115·8 | 115·5 | 115·6 | |

| 6 | 6·79 (d; 8·0) | 6·82 (dd; 8·0; 2·0) | 7·37 (d; 8·2) | 6 | 120·0 | 120·1 | 129·1 | |

| 7 | 7·14 (d; 15·5) | 7·17 (d; 15·5) | 7·24 (d; 15·5) | 7 | 138·5 | 139·3 | 138·4 | |

| 8 | 6·45 (d; 15·5) | 6·41 (d; 15·5) | 6·52 (d; 15·5) | 8 | 119·2 | 118·1 | 119·0 | |

| 9 | – | – | – | 9 | 164·5 | 165·2 | 164·8 | |

| DOPA (1) | 1′ | – | – | – | 1′ | 130·0 | 127·8 | 128·7 |

| Tyrosine (2 and 3) | 2′ | 6·62 (s) | 7·01 (d; 8·0) | 6·99 (d; 8·0) | 2′ | 117·0 | 129·9 | 130·0 |

| 3′ | – | 6·63 (d; 8·0) | 6·60 (d; 8·0) | 3′ | 144·7 | 114·7 | 114·7 | |

| 4′ | – | – | – | 4′ | 143·3 | 155·7 | 155·6 | |

| 5′ | 6·52 (d; 8·0) | 6·63 (d; 8·0) | 6·60 (d; 8·0) | 5′ | 115·0 | 114·7 | 114·7 | |

| 6′ | 6·39 (d; 8·0) | 7·01 (d; 8·0) | 6·99 (d; 8·0) | 6′ | 120·0 | 139·9 | 130·0 | |

| 7′ | 2·94 (dd; 4·4; 13·3) | 2·99 (dd; 4·4; 13·4) | 3·02 (dd; 3·7; 13·4) | 7′ | 37·2 | 36·2 | 36·6 | |

| 2·75 (dd; 6·7; 13·3) | 2·78 (dd; 8·7; 13·4) | 2·80 (dd; 7·9; 13·4) | ||||||

| 8′ | 4·21 (m) | 4·41 (m) | 4·35 (m) | 8′ | 55·8 | 54·4 | 55·0 | |

| 9′ | – | – | – | 9′ | 174·7 | 174·3 | 174·4 | |

| NH 7·48 (d; 6·4) | NH 8·04 (broad singulet) | NH 7·79 | ||||||

| 4′ OH 9·14 | 4′ OH 9·12 |

* Values shown in brackets are shifts and J values (Hz).

Quantitative studies of variations in phenolics during somatic embryogenesis.

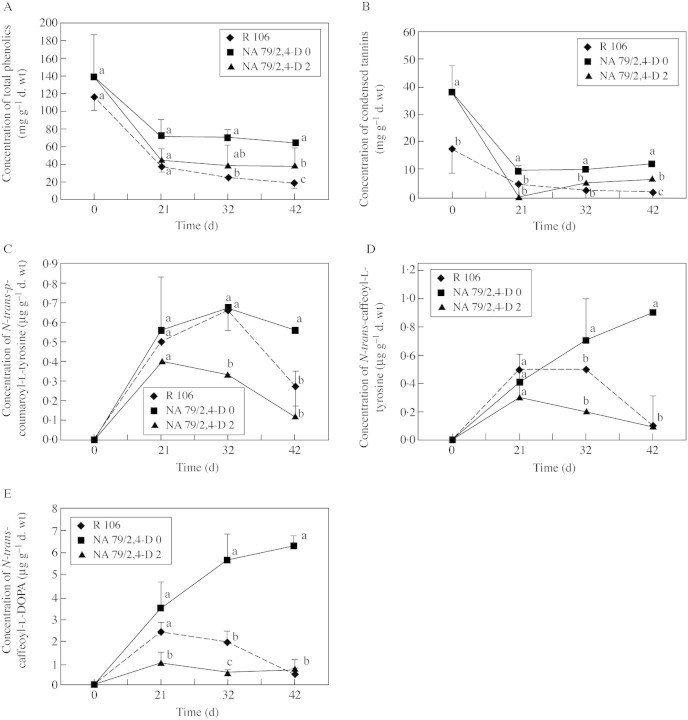

Total phenolics, condensed tannins, N‐trans‐caffeoyl‐l‐DOPA, N‐trans‐caffeoyl‐l‐tyrosine and N‐trans‐p‐coumaroyl‐l‐tyrosine were measured during tissue culture on two genotypes differing in their embryogenic capacity (Fig. 4). R 106 was non‐embryogenic (Table 5) and NA 79 was non‐embryogenic or embryogenic, depending on the 2,4‐D concentration of the callogenesis medium: 0 or 2 mg l–1 (Table 5).

Fig. 4. Variation in the concentration of different polyphenolic compounds throughout the somatic embryogenesis process for non‐embryogenic genotype R 106 and for embryogenic genotype NA 79 cultured either under non‐embryogenic conditions (without 2,4‐D) or under embryogenic conditions (with 2,4‐D). A, Total phenolics; B, condensed tannins; C, N‐trans‐p‐coumaroyl‐l‐tyrosine; D, N‐trans‐caffeoyl‐l‐tyrosine; E, N‐trans‐caffeoyl‐l‐DOPA. Vertical bars represent standard deviations. For each date, points followed by different letters are significantly different at the 5 % level, with the Newman–Keuls test.

Table 5.

Somatic embryogenesis efficiency of two cocoa genotypes

| Genotype | 2,4‐D in induction medium (mg l–1) | No. of cultured explants | Embryogenic explants (%) |

| R 106 | 2 | 69 | 0 |

| NA 79 | 0 | 54 | 0a |

| 2 | 69 | 69·6b |

Values followed by different superscripts letters are significantly different at the 5 % level, with the Newman–Keuls test.

Total phenolics and tannins evolved in a similar way during tissue culture, irrespective of genotype and embryogenic capacity (Fig. 4A and B). They were abundant in flowers, but their concentrations decreased during the process. However, from day 21 for tannins and day 32 for total phenolics, significant concentrations were observed in different calli, with non‐embryogenic R 106 calli containing the smallest amount of phenolics and tannins. These compounds were intermediately concentrated in embryogenic genotype NA 79 cultured under conditions in which embryogenic capacity was expressed. Conversely, total phenolics and tannins were significantly higher in NA 79 explants placed under conditions in which embryogenic capacity could not be expressed (no 2,4‐D in the medium). Under these conditions, a histological study showed that cells of the staminodes/anthers hardly divided, accumulated starch and phenolics, and finally degenerated (data not shown).

The kinetics of the three identified hydroxycinnamic amides were different from those of total phenolics and tannins (Fig. 4C–E). They were absent from flowers, but their synthesis started and increased with tissue culture until approx. day 21. In the second phase of the culture, these compounds decreased except in explants of NA 79 on 2,4‐D‐free medium where they continued to increase. The clearest example is that of clovamide or N‐trans‐caffeoyl‐l‐DOPA, the most abundant hydroxycinnamic amide. In the second phase of the culture, it was significantly higher in NA 79 calli on 2,4‐D free medium. Between R 106 and embryogenic NA 79, this compound was significantly higher in non‐embryogenic R 106. This difference disappeared at the end of the culture process. The same tendency was noticed also for the other two hydroxycinnamic amides.

DISCUSSION

Cocoa flowers contained different polyphenolics: hydroxycinnamic acids were located on the periphery of organs, except in the ovary where they were present in parenchyma cells and ovules; tannins and anthocyanins were located both in the epidermis of different floral parts and also internally; anthocyanins were restricted to ornamentation in petals and staminodes. This mainly external positioning of polyphenolics has been observed in other plants. Tannins are present in fruit pericarp and in the root and stem cortex of Struthanthus vulgaris (Salatino et al., 1993). In the radicle of germinating Brassica napus zygotic embryos, phenolic compounds are located outside the epidermis (Zobel et al., 1989). This external location might suggest a protective chemical‐barrier role for phenolics against damaging environmental factors.

A comparison between cultured floral explants and derived calli, by both histochemistry and chromatography, revealed clearly the synthesis of new phenolic compounds in the calli, including four caffeic derivatives and three hydroxycinnamic amides. The same profile was observed irrespective of the callus stage and genotype. Synthesis of new molecules in cultured tissues compared with the mother plant is sometimes observed. In Eucalyptus robusta, calli derived from seedling hypocotyls had the same qualitative phenolic content as wood and bark, although quantitative differences were observed (Yamaguchi et al., 1986). In Crataegus calli, phenolic composition was simpler than in floral buds (Bahorun et al., 1994). Conversely, on a different original explant of the same species, shoot tips indicated synthesis of new flavonoids, and several benzoic and hydroxycinnamic acid amides in the calli (Kartnig et al., 1993). Tahrouch‐Skouri et al. (1993) showed one newly synthesized caffeic acid heterosidic ester in leaf calli. Surprisingly, the phenolic composition of cocoa calli was closer to that of cocoa beans than to that of the staminodes from which they were derived. The synthesis of new compounds could be due to cellular dedifferentiation and/or to a response to wounding and stress, induced by in vitro culture conditions.

Of the new synthesized phenolics, the three most abundant were identified as hydroxycinnamic amides. Both N‐trans‐caffeoyl‐l‐DOPA, or clovamide, and N‐trans‐p‐coumaroyl‐l‐tyrosine, a deoxy analogue of clovamide: deoxyclovamide, have already been identified in the tropical tree Dalbergia melanoxylon (Van Heerden et al., 1980) and more recently in cocoa liquor (Sanbongi et al., 1998). In this paper, the antioxidant effect of these compounds in vitro has been demonstrated. Clovamide was first reported in Trifolium pratense stems and leaves (Yoshihara et al., 1974). The presence of these two compounds has been demonstrated in cocoa beans and, for the first time, in calli. This is also the first report of N‐trans‐caffeoyl‐l‐tryosine in cocoa beans and calli, although it has already been identified in Angola green coffee beans (Clifford et al., 1989). The physiological roles of hydroxycinnamic amides are not clear. Hydroxycinnamic amides with aliphatic amines (spermidine, putrescine) are widely distributed in flowering plants (Martin‐Tanguy et al., 1978) and are often characteristic of ovaries and anthers (Ponchet et al., 1982; Leubner‐Metzger and Amrhein, 1993) as well as of maize embryos and endosperm tissues where they accumulate (Martin‐Tanguy et al., 1982). Hydroxycinnamic amides containing an amino acid have been found more rarely, and only in tissue cultures. Arabidopsis thaliana cell suspensions synthesized coumaroylaspartate (Mock et al., 1993). Feruloylaspartate was identified in Beta vulgaris (Bokern et al., 1991a) and in Chenopodium rubrum (Bokern et al., 1991b) cell cultures. No physiological role was suggested. In Ephedra distachya, as the production of p‐coumaroylglycine and p‐coumaroylalanine by cell suspensions was induced after adding yeast extracts to the medium, Song et al. (1992) suggested that these compounds might be produced as phytoalexins in intact plants. In a review on hydroxycinnamates and their conjugates, Kroon and Williamson (1999) focused on their potent in vitro antioxidant activity. Pearce et al. (1998) demonstrated the synthesis of E‐feruloyltyramine and E‐p‐coumaroyltyramine in response to wounding in tomato leaves. In cocoa beans and calli, because of the antioxidant nature of N‐trans‐p‐coumaroyl‐L‐tyrosine and N‐trans‐caffeoyl‐l‐DOPA, or clovamide (Sanbongi et al., 1998), the two most abundant hydroxycinnamic amides in calli, the synthesis of these compounds could be a protective reaction against stress.

The purpose of the final experiments described here was to identify a possible relationship between phenolic composition and embryogenic capacity. At the flower level, no significant difference, either quantitative or qualitative, in phenolic composition was found between embryogenic NA 79 and non‐embryogenic R 106 genotypes. In Sorghum bicolor, Jabri et al. (1989) observed a relationship between callogenesis and embryogenic aptitude and the concentration of tannins in the plant. A tannin‐poor variety regenerated somatic embryos; a variety moderately rich in tannins only produced calli; and a tannin‐rich variety barely produced any calli. At the cocoa callus level, during the callogenesis and somatic embryogenesis processes, no clear relationship was detected between the presence or absence of polyphenolics and embryogenic or non‐embryogenic response. In date palm, El Hadrami (1995) distinguished between embryogenic calli and multiplying calli by the presence and accumulation of new flavones and flavonols. However, quantitatively speaking, some significant differences were observed. Under embryogenic conditions (NA at 79, 2,4‐D at 2 mg l–1), the concentrations of total phenols and tannins were intermediate compared with their lower concentrations under non‐embryogenic conditions (R 106, 2,4‐D at 2 mg l–1) and to their higher concentrations under non‐embryogenic condition (NA 79, 2,4‐D at 0 mg l–1). Embryogenic capacity, therefore, seemed to be associated with a balanced concentration of phenolics. High concentrations of hydroxycinnamic acid amides were associated with the non‐embryogenic response. Owing to the antioxidant nature of these molecules (Pearce et al., 1998; Sanbongi et al., 1998; Kroon and Williamson, 1999) they are probably more related to stress conditions than to the embryogenic status itself. The more the tissues were stressed, the more of these substances were synthesized. Somatic embryogenesis could be expressed under less stressful conditions. Apparently, this reaction against stressful conditions was not sufficient to protect the tissues. It is planned to carry out a more detailed study of the different protective systems that protect cocoa tissues against stress in vitro (e.g. detoxification). This should help to define recalcitrance.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Annie Heitz (Centre de Biochimie structurale, Faculté de Pharmacie, 34060 Montpellier, France) for the MNR analysis, and Peter Biggins for checking the English.

Supplementary Material

Received: 4 November 2002;; Returned for revision: 13 May 2003. Accepted: 18 June 2003; Published electronically: 21 August 2003

References

- AlemannoL, Berthouly M, Michaux‐Ferrière N.1996. Histology of somatic embryogenesis from floral tissues in Theobroma cacao L. Plant Cell Tissue and Organ Culture 46: 187–194. [Google Scholar]

- AlemannoL, Berthouly M, Michaux‐Ferrière N.1997. A comparison between Theobroma cacao L. zygotic embryogenesis and somatic embryogenesis from floral explants. In vitro Cellular and Develop mental Biology 33: 163–172. [Google Scholar]

- BahorunT, Trotin F, Vasseur J.1994. Comparative polyphenolic productions in Crataegus monogyna callus cultures. Phytochemistry 37: 1273–1276. [Google Scholar]

- BensonEE.2000.In vitro plant recalcitrance: an introduction. In vitro Cellular and Developmental Biology 36: 141–148. [Google Scholar]

- BokernM, Heuer S, Wray V, Witte L, Macek T, Vanek T, Strack D.1991a. Ferulic acid conjugates and betacyanins from cell cultures of Beta vulgaris. Phytochemistry 30: 3261–3265. [Google Scholar]

- BokernM, Wray V, Strack D.1991b. Accumulation of phenolic acid conjugates and betacyanins, and changes in the activities of enzymes involved in feruloylglucose metabolism in cell‐suspension cultures of Chenopodium rubrum L. Planta 184: 261–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CliffordMN, Kellard B, Ah‐Sing E.1989. Caffeoyltyrosine from green Robusta coffee beans. Phytochemistry 28: 1989–1990. [Google Scholar]

- DaiGH, Andary C, Cosson LM, Boubals D.1994. Polyphenols and resistance of grapevines (Vitis spp.) to downy mildew (Plasmopara viticola). Acta Horticulturae 381: 763–766. [Google Scholar]

- DaiGH, Andary C, Cosson LM, Boubals D.1995. Involvement of phenolic compounds in the resistance of grapevine callus to downy mildew (Plasmopara viticola). European Journal of Plant Pathology 101: 541–547. [Google Scholar]

- ElHadramiI.1995.L’embryogenèse somatique chez Phoenix dactylifera L.: quelques facteurs limitants et marqueurs biochimiques. Thèse d’Etat, University Cadi Ayyad Marrakech, Morocco. [Google Scholar]

- GriffithsLA.1958. Phenolic acids and flavonoids of Theobroma cacao L. Separation and identification by paper chromatography. Biochemistry Journal 70: 120–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JabriA, Chaussat R, Jullien M, Le Deunff Y.1989. Aptitude à la callogenèse et à l’embryogenèse somatique de fragments foliaires de trois variétés de sorgho (Sorghum bicolor L. Moench) avec et sans tannins. Agronomie 9: 101–107. [Google Scholar]

- KartnigT, Kögl G, Heydel B.1993. Production of flavonoids in cell cultures of Crataegus monogyna Planta Medica 59: 537–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KimH, Keeney P.1983.Polyphenols–tannins in cocoa beans 37th PMCA Production Conference, 26–28 April, Lancaster, PA, pp. 60–63. [Google Scholar]

- KroonPA, Williamson G.1999. Hydroxycinnamates in plants and food: current and future perspectives. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 79: 355–361. [Google Scholar]

- Leubner‐MetzgerG, Amrhein N.1993. The distribution of hydroxy cinnamoyl putrescines in different organs of Solanum tuberosum and other solanaceous species. Phytochemistry 32: 551–556. [Google Scholar]

- LiZ, Traore A, Maximova S, Guiltinan M.1998. Somatic embryogenesis and plant regeneration from floral explants of cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) using thidiazuron. In vitro Cellular and Developmental Biology 34: 293–299. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez‐BaezO, Bollon H, Eskes AB, Pétiard V.1993. Embryogenèse somatique de cacaoyer Theobroma cacao L. à partir de pièces florales. Compte Rendus de l’Académie des Sciences, Serie 6 316: 579–584. [Google Scholar]

- Martin‐TanguyJ, Cabanne F, Perdrizet E, Martin C.1978. The distribution of hydroxycinnamic acid amides in flowering plants. Phytochemistry 17: 1927–1928. [Google Scholar]

- Martin‐TanguyJ, Perdrizet E, Prevost J, Martin C.1982. Hydroxycinnamic acid amides in fertile and cytoplasmic male sterile lines of maize. Phytochemistry 21: 1939–1945. [Google Scholar]

- MockHP, Wray V, Beck W, Metzger JW, Strack D.1993. Coumaroylaspartate from cell suspension cultures of Arabidopsis thaliana Phytochemistry 34: 157–159. [Google Scholar]

- MurashigeT, Skoog F.1962. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiologia Plantarum 15: 473–479. [Google Scholar]

- PearceG, Marchand PA, Griswald J, Lewis NG, Ryan CA.1998. Accumulation of feruloyltyramine and p‐coumaroyltyramine in tomato leaves in response to wounding. Phytochemistry 47: 569–664. [Google Scholar]

- PonchetM, Martin‐Tanguy J, Marais A, Martin C.1982. Hydroxycinnamoyl acid amids and aromatic amines in the inflorescences of some araceae species. Phytochemistry 21: 2865–2869. [Google Scholar]

- SalatinoA, Kraus JE, Salatino MLF.1993. Contents of tannins and their histological localization in young and adult parts of Struthanthus vulgaris Mart. (Loranthaceae). Annals of Botany 72: 409–414. [Google Scholar]

- SanbongiC, Osakabe N, Natsume M, Takizawa T, Gomi S, Osawa T.1998. Antioxidative polyphenols isolated from Theobroma cacao Journal of Agriculture and Food Chemistry 46: 454–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SongKSK, Ishikawa Y, Kobayashi S, Sankawa U, Ebizuka Y.1992.N‐Acylamino acids from Ephedra distachya cultures. Phytochemistry 31: 823–826. [Google Scholar]

- Tahrouch‐SkouriS, Andary C, Macheix JJ.1993. Le greffage induit une modification de l’expression du métabolisme phénolique chez Jasminum grandiflorum Compte Rendus de l’Académie des Sciences, Serie 3 316: 293–297. [Google Scholar]

- Van HeerdenFR, Brandt EV, Roux DG.1980. Isolation and synthesis of trans‐ and cis‐(–)‐clovamides and their deoxy analogues from the bark of Dalbergia melanoxylon Phytochemistry 19: 2125–2129. [Google Scholar]

- YamaguchiT, Fukuzumi T, Yoshimoto T.1986. Phenolics of tissue cultures from Eucalyptus spp. I. Analysis of phenolics in callus of Eucalyptus robusta Mokuzai Gakkaishi 32: 203–208. [Google Scholar]

- YoshiharaT, Yoshikawa H, Sakamura S, Sakuma T.1974. Clovamides; L‐Dopa conjugated with trans‐ and cis‐(–)‐caffeic acids in red clover. Agricultural and Biological Chemistry 38: 1107–1109. [Google Scholar]

- ZobelA, Kura M, Tykarska T.1989. Cytoplasmic and apoplastic location of phenolic compounds in the covering tissue of the Brassica napus radicle between embryogenesis and germination. Annals of Botany 64: 149–157. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.