This study aimed at the recognition that the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act could potentially greatly impact how local health departments function in providing public health services.

Keywords: Big City Health Coalition, health care reform, Affordable Care Act, public health practice, urban health

Abstract

Context:

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) is changing the landscape of health systems across the United States, as well as the functioning of governmental public health departments. As a result, local health departments are reevaluating their roles, objectives, and the services they provide.

Objective:

We gathered perspectives on the current and future impact of the ACA on governmental public health departments from leaders of local health departments in the Big Cities Health Coalition, which represents some of the largest local health departments in the country.

Design:

We conducted interviews with 45 public health officials in 16 participating Big Cities Health Coalition departments. We analyzed data reflecting participants' perspectives on potential changes in programs and services, as well as on challenges and opportunities created by the ACA.

Results:

Respondents uniformly indicated that they expected ACA to have a positive impact on population health. Most participants expected to conduct more population-oriented activities because of the ACA, but there was no consensus about how the ACA would impact the clinical services that their departments could offer. Local health department leaders suggested that the ACA might create a broad range of opportunities that would support public health as a whole, including expanded insurance coverage for the community, greater opportunity to collaborate with Accountable Care Organizations, increased focus on core public health issues, and increased integration with health care and social services.

Conclusions:

Leaders of some of the largest health departments in the United States uniformly acknowledged that realignments in funding prompted by the ACA are changing the roles that their offices can play in controlling infectious diseases, providing robust maternal and child health services, and more generally providing a social safety net for health care services in their communities. Health departments will continue to need strong leaders to strengthen and maintain their critical role in protecting and promoting the health of the public they serve.

Background

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) reduced the number of Americans without health insurance by 9.3 million between 2013 and 2014.1 However, expanding coverage has had unanticipated impacts for the nation's public health system, particularly in terms of the clinical care services they offer, including infectious disease control, family planning, maternal and child health, and other specific services.2,3 Of the nation's 2800 local health departments (LHDs),

90% provide immunizations to children and adults

75% treat tuberculosis

60% provide STD treatment

50% provide family planning services

25% treat HIV/AIDS

10% provide comprehensive primary care.4

Local health departments are reexamining their roles in the community, particularly for individual clinical care services.5–10 Although the ACA does mandate additional coverage for preventive services, there may be a continuing need for safety net clinical services.3,6,11–13 Local health departments may choose to discontinue clinical services in favor of activities that have a population-oriented focus, in keeping with changes that have been recommended by an Institute of Medicine committee more than 25 years ago.14–17 Alternatively, LHDs may continue to provide clinical care that addresses unmet needs in their communities and/or generates revenue.

Little is known about the attitudes of local public health leaders toward the ACA or their decision-making processes in reaction to the health systems and community changes prompted by its enactment. Addressing this gap in knowledge is important, given the role of LHDs as a safety net provider in their respective communities. We conducted a mixed-methods study among leaders in 16 large, urban LHDs. Our goal was to assess leaders' perspectives, attitudes, and concerns regarding the impact of the ACA on health systems, on the communities they serve, and on their departments. This study was prompted by the recognition that the ACA could potentially greatly impact how LHDs function in providing these and other public health services.

Methods

We conducted the study as part of a larger assessment of the capacities, needs, and priorities of members of the Big Cities Health Coalition (BCHC); detailed methods used in the larger assessment have been described elsewhere.18 The BCHC is a group within the National Association of County & City Health Officials with 20 members*, representing some of the largest LHDs in the country, including those in Atlanta, Baltimore, Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, Dallas, Denver, Detroit, Houston, Los Angeles, Miami, New York, Philadelphia, Phoenix, San Antonio, San Diego, San Francisco, San Jose, Seattle, and Washington, DC.

The study focused on leadership perceptions and attitudes about the potential impacts of ACA. We used a mixed-methods design, beginning with interviews and followed by a Web-based survey. Participants included 45 leaders from 16 participating BCHC LHDs. Each participant held 1 of 3 specific positions: local health official (LHO), chief of policy, or chief science/medical officer. Since LHDs are often structured differently, participants came from departments that did not necessarily have a staff member in each of these positions (eg, 3 LHDs did not have a chief of policy position). All respondents participated in a semistructured interview portion of the study and were asked the same questions. The Web-based survey questions were separated into different modules, with questions regarding the impacts of ACA on specific programs directed only to the 16 LHOs. The questions were closed-ended and focused mainly on organizational characteristics and anticipated programmatic changes. Questions regarding expected changes in provision of services due to the ACA were accompanied by response options on a 7-point ordinal Likert scale. Response options included “My LHD doesn't currently perform this activity and I expect it would not start performing it”; “I expect the LHD will not provide this activity”; “I expect the LHD to perform much less of this activity”; “I expect the LHD to perform somewhat less of this activity”; “I expect the LHD to perform somewhat more of this activity”; and “I expect the LHD to perform much more of this activity.”

We collected interview and survey data between August and October 2013. Interviews lasted 1 hour, on average. Qualitative data were independently coded thematically by 2 researchers and were managed and analyzed in NViVo 10 (QSR International, Cambridge, Massachusetts). Data were analyzed in aggregate, as well as by position type and by location. Quantitative data were cleaned, managed, and analyzed in Stata 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas). Integration of data occurred during analysis, per the embedded mixed-methods design.19 Both instruments were pretested with 5 people who had backgrounds in state and/or local public health.

Results

Forty-five respondents participated in the interviews. Six respondents from 2 LHDs did not respond to requests for interviews. Study participants were leaders of 16 of the 18 LHDs in the BCHC at the time of the study. Twenty-five respondents had a legal or medical degree (JD or MD), 6 had a PhD or DrPH, 12 had a master's degree, and 2 had a bachelor's degree as the highest level of education. At the time of interviews (Fall 2013), participants had served in their current positions for an average of 3.4 years (median, 3.0).

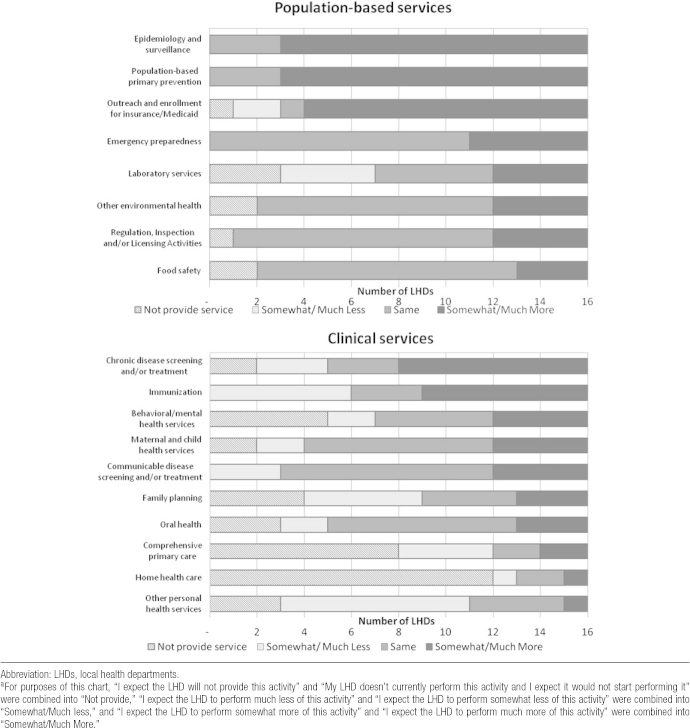

Answers to the closed-ended survey questions by the 16 LHOs also reflected a wide range of expectations about possible changes ACA might bring to specific programs and services (Figure). Generally, participants agreed that population-oriented services would increase in scope and scale, and that the information-related services provided by public health offices would grow in importance. Specifically, 13 of the 16 LHOs said they expected to do more epidemiology and surveillance, 13 expected to do more population-oriented primary prevention, and 12 expected to conduct more outreach/enrollment for health care exchanges and/or Medicaid expansion. There was no consensus about expected changes in clinical care provision. Eight LHOs expected their offices to provide more screening or treatment of chronic disease, 3 LHOs expected to provide somewhat less or much less screening and treatment, and 2 expected that their departments would provide no chronic disease screening or treatment. There was also no consensus about how ACA might impact immunization services. Seven LHOs expected their offices to provide more immunization services, while 6 expected to provide fewer. Several LHOs did not provide certain direct clinical services (most notably behavioral health care) at the time of the study and did not anticipate that they would be doing so in the future. Respondents, respectively, noted that the uncertainty about the continued provision of clinical care services was due both to the complex local political environment and to the fact that ACA was directed at health care reform, rather than public health, per se.

FIGURE •.

Expected Change in Provision of Services at Big Cities Health Coalition LHDs Due to the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (n = 16)a

Examples of Potential Service Changes

Participants said that they believed that 3 particular categories of services might be affected by the ACA: epidemiology/surveillance, safety net clinical services, and immunizations. Thirteen LHOs expected that the ACA might change surveillance activities, perhaps substantially. Eleven respondents noted that a significant amount of new health data might become available through health information exchanges, and that health departments might be best positioned to collect, analyze, and report these data to community partners. The leaders said that they expected that the ACA would prompt more epidemiology and surveillance work, although some expressed concern about funding for these and other core services.

A majority of participants said that they felt that ACA would likely precipitate changes to safety net clinical services. Respondents from 13 cities said they were specifically concerned that the ACA might cause their departments to lose funding, especially for clinical services. In their view, safety net clinical services could be cut if policymakers perceived that expanded health insurance coverage would eliminate the need for safety net services. However, several leaders expressed concern that, regardless of insurance status, demand for services such as treatment of sexually transmitted diseases or family planning would continue. From their perspective, needs of the uninsured will persist, and some insured patients will continue to want to avoid engaging their normal care providers or billing processes for certain treatments.

Several respondents were concerned that there could be decreased immunization rates in their jurisdictions. These respondents noted that expanded health insurance coverage under ACA might change the availability of immunization services, and that despite continued funding for programs such as Vaccines for Children, a confluence of additional financial and policy pressures may lead to a decrease in funding for vaccines that were previously provided by health departments. In addition, participants noted that private providers also might be discouraged from administering vaccines because of both relatively low reimbursement rates and new Centers for Disease Control and Prevention regulations regarding vaccine storage. Several respondents also said that a relatively large proportion of their population was covered by the “grandfather clause” provision of the ACA (>50% of the residents younger than 65 years in one jurisdiction), which does not require insurers to cover preventive treatments, such as vaccines, at no cost to patients. Leaders from 2 cities thought that these factors, taken together, might mean that a substantial number of people may lose both a provider and a payer for immunization services that they had had prior to ACA.

Potential Opportunities Afforded to LHDs by the ACA

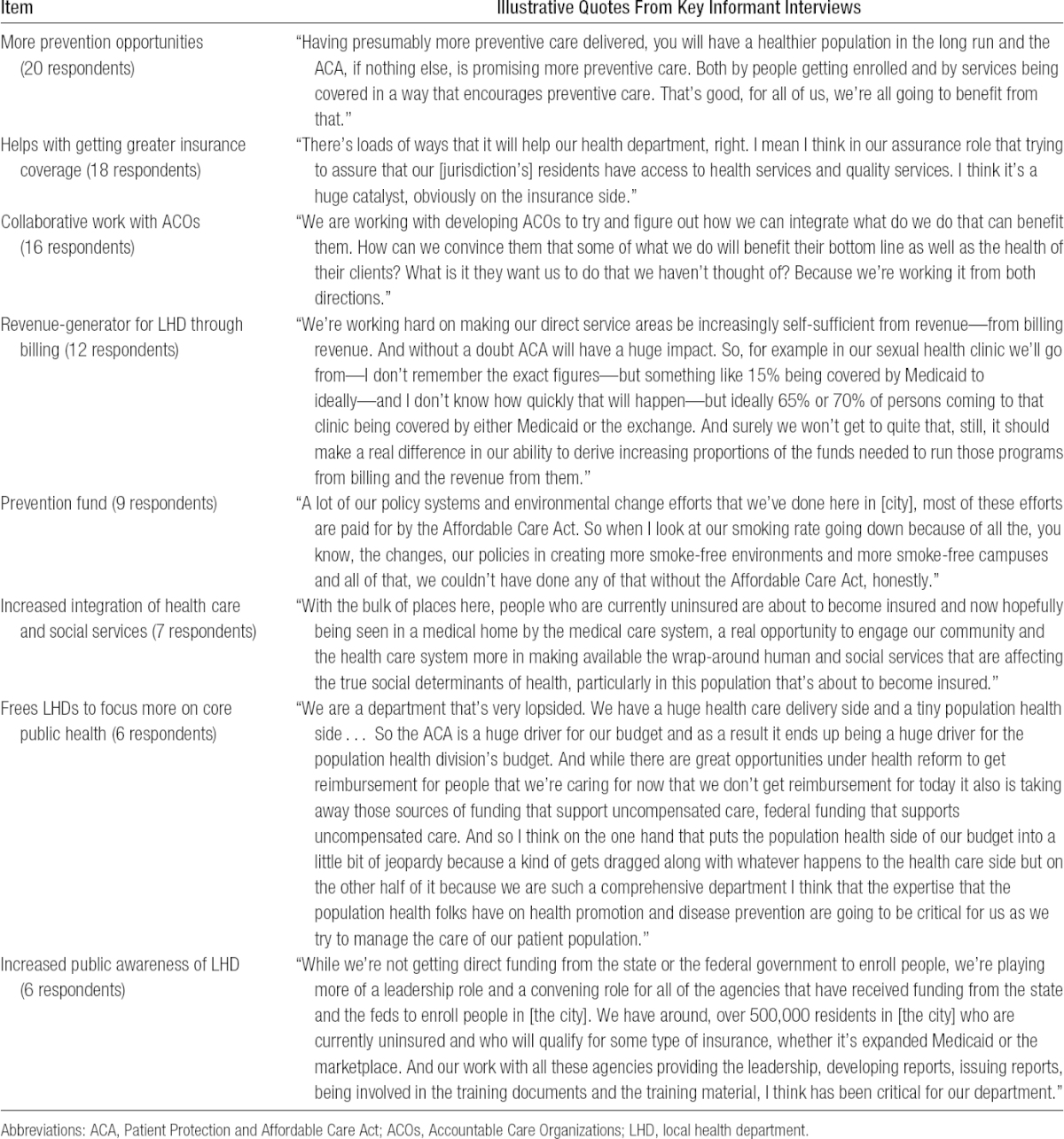

Participants uniformly expressed a belief that ACA would be a boon to population health and would also benefit government efforts to improve public health. Respondents also identified specific potential positive impacts for public health and possible opportunities for their health departments as a result of ACA implementation (Table 1). Respondents from 12 LHDs felt that ACA provided more opportunities for prevention in public health, and respondents from a different set of 12 LHDs said that they felt that greater insurance coverage would benefit population health. Respondents from 10 LHDs thought that collaboration with Accountable Care Organizations held potential to improve population health, and respondents from 9 LHDs said that they thought that additional billing/reimbursement opportunities could be a revenue generator for their LHDs. Five respondents thought that it was too early to tell, because of uncertainty about how ACA would be implemented in their jurisdiction, and 2 said that they did not think that the ACA would help their LHD at all. Nine respondents spontaneously mentioned that the Public Health Prevention Fund created by the ACA could significantly enhance public health by supporting population-oriented programs and services, despite it being a political target.

TABLE 1 •. Illustrative Quotes From Leaders of BCHC LHDs on the Potential Opportunities to Their LHD Due to the ACA.

Potential Challenges Due to ACA

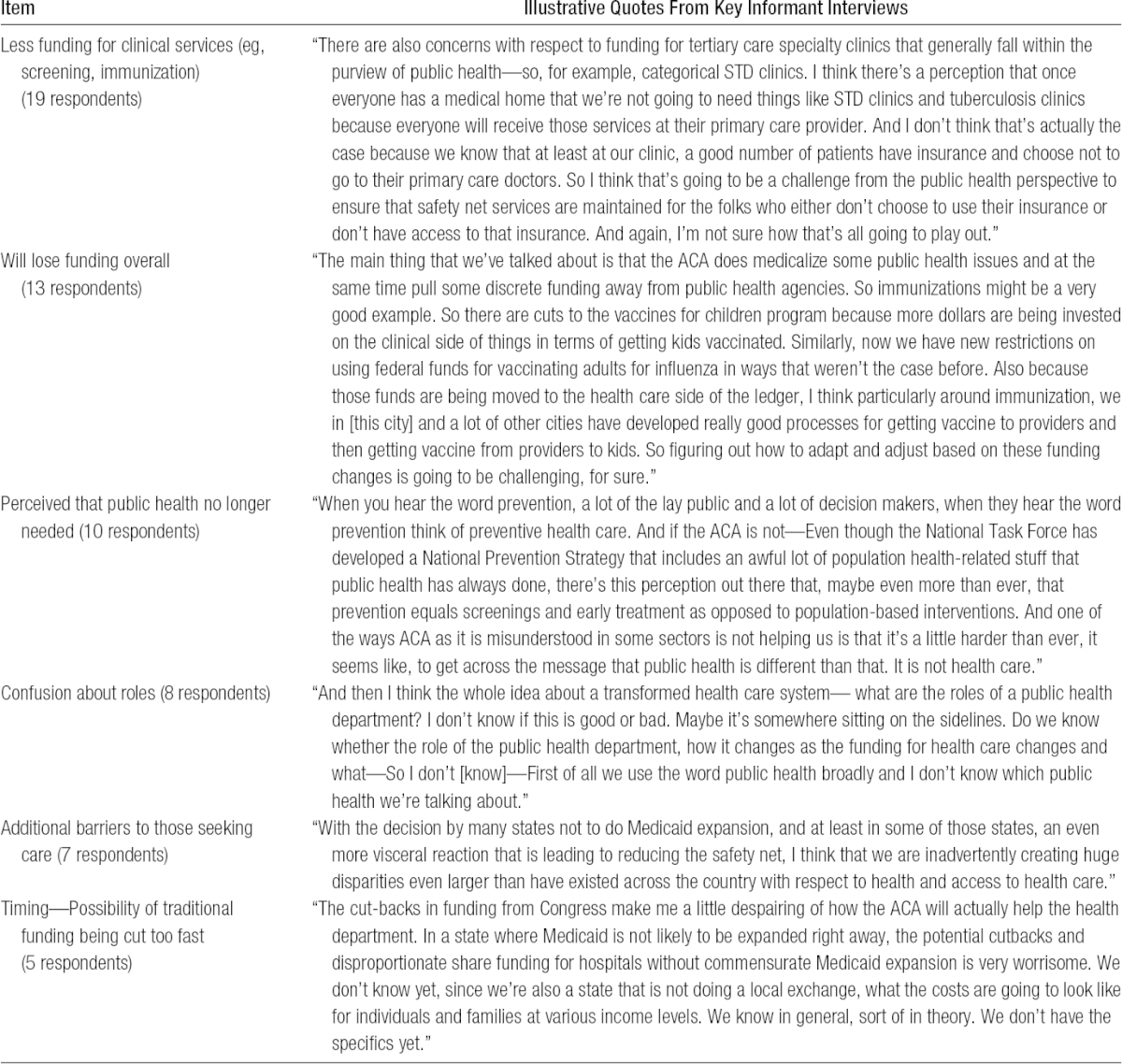

Respondents identified 6 categories of potential challenges for LHDs created by the ACA (Table 2), the most common being decreased funding. At least 1 respondent from 12 of the LHDs thought that funding for clinical services might be reduced by policy makers who believe that the expanded health insurance coverage created by the ACA would eliminate the need for clinical services. All respondents from 3 LHDs agreed on this point. In addition, leaders said that they thought categorical grants from the federal government may be at risk for reduction before their departments were able to find alternative sources of revenue, such as reimbursement through Medicaid. Finally, participants from 10 cities noted that they expected the budgets of health departments to be cut broadly, especially to help pay for Medicaid expansions in cash-strapped states.

TABLE 2 •. Illustrative Quotes From Leaders of Big Cities Health Coalition Local Health Departments on the Potential Downsides to the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act for Their Agency.

Respondents from 10 LHDs were concerned that both the policy makers and the public would think that public health services were no longer necessary because of the expanded insurance coverage for all citizens provided by ACA. Respondents felt that a change in demand for public health services might be more likely if policy makers assumed that patients would prefer to see their primary care physicians or visit their medical home, rather than to turn to services traditionally provided by public health departments. Three respondents believed that their undocumented immigrant communities would still have substantial problems accessing needed health care (Table 2).

Participants also noted significant confusion about roles and responsibilities among partners in the health care community since the passage of the ACA. Several said that although the ACA might allow their departments to focus on population-oriented work, they expected that their department would be providing more clinical services, and perhaps new services such as behavioral health treatment. These respondents pointed to continuing needs for these kinds of services in their communities as ones that might not be addressed by the ACA. They also noted that reimbursement for clinical services could be a revenue driver for health departments.

Collaborations Between Public Health and Primary Care Under ACA

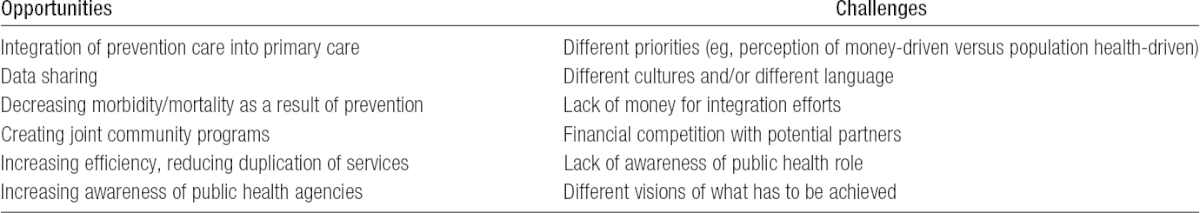

Participants also noted that implementation of the ACA might significantly increase opportunities for collaboration between public health departments and health care providers, especially primary care providers. Although the majority of leaders in this study said that their offices were already connected with the primary care community in their area to some degree, the degree of communication often varied. Participants discussed both challenges and opportunities (summarized in Table 3) associated with more collaboration between the 2 fields, including greater integration of preventive care into primary care (14 respondents), increased data sharing between primary care and public health (11 respondents), and decreased morbidity and mortality due to an increasing focus on prevention (8 respondents).

TABLE 3 •. A Summary of Participant Perspectives on the Opportunities and Challenges Relating to Closer Connections Between Public Health and Primary Care as Identified by Big Cities Health Coalition Members.

Several respondents also noted that more collaboration could lead to business models that could support ongoing partnerships between public health and primary care professionals. As one respondent stated:

If we each do our jobs well, our jobs will both be easier. So if our primary care provider partners are truly promoting healthy eating, smoking cessation, exercise, all of those good qualities of living well, I think we'll see the health of the public improve dramatically. And I think if we as a public health force are really doing our jobs well, we will be here to support our primary care providers more, not only through clinical guidelines but also by implementing systematic changes [and] environmental changes that will promote health and make it easier for our primary care providers to care for their patients.

Respondents also discussed community health needs assessments (CHNAs), and most said that they felt that CHNAs present an opportunity for increased collaboration between public health departments and health care providers. According to new IRS regulations, nonprofit hospitals and health care systems must connect with public health experts during their CHNA as part of community benefit requirements. Leaders from 15 of the 16 BCHC LHDs in the study said that they were already developing CHNAs with local nonprofit hospitals/systems. In these collaborations, BCHC LHDs were providing hospitals with analyses of health data from a variety of sources: 12 were providing hospitals with analysis of local data, 6 were providing analysis of state data, 4 were providing analysis of hospital-generated data, and 3 were providing analysis of national data. Eight of the 16 also said that they were working with hospitals or health care systems in the health improvement planning associated with CHNAs. Although the exact roles of the health department and hospitals in the CHNA vary from community to community, participants in our study indicated that their LHDs are playing a central role in data analysis and policy design and are working with otherwise-competing health systems to engage their community overall, beyond their catchment areas. As one respondent said,

[Hospitals] are all required to do these needs assessments that public health agencies have been doing since the beginning of time. And none of them want to be told what to do, but I think as they rethink their charity care, there's a tremendous opportunity for prevention. And one of the things I'm working on now is trying to frame the findings of their individual needs assessments so we can present it to them and show them the significant consensus that they have—the overlap in their service areas—and then also give them guidance on what's known to work as interventions.

Participants identified differences in communications and priorities as significant challenges to this type of collaboration. They felt, for example, that primary care and public health professionals “spoke” different languages, that the 2 groups had different priorities, and that there was a lack of awareness and knowledge about each other's professions and values. In addition, a perceived lack of interest on the part of primary care was troubling to several of the leaders participating in the interview, as illustrated below.

You know, we've tried a lot. We've met with all the pioneer ACOs. We've got a bunch of proposals on the table. We've submitted some joint grants with some of the community health centers. But I would say nothing's really happening yet. So we're trying to identify where there might be opportunities for a common agenda and common work, but it's not like everybody is beating down our doors saying, ‘Oh, we want to partner with you guys!’

Discussion

The participants in our study, all leaders of large, urban LHDs, said that they were optimistic that the ACA would result in a net benefit both for governmental public health and population health. They believed that expanded health insurance coverage would somewhat alleviate stress on the existing safety net services by providing access to care by other health care providers. They also felt that ACA would help public health departments strengthen their roles as analysts of health information, better regulate factors that impact public health, and more effectively serve as conveners of collaborations that can promote healthy behaviors in communities.

The ACA has profound implications for how governmental public health entities are able to provide services to improve population health. Leaders of public health departments now must make critical choices about what roles they plan to play in the ACA environment. In our study, most respondents said that they plan to provide more population-oriented services. However, most were not clear about the clinical care services they would provide, although they were planning to decrease or discontinue some types of clinical care services, acknowledging that this action may result in reduced revenue used to support other core public health programs. Participants suggested that the variation in the number and kind of clinical services that LHDs may provide is driven both by the services now offered and by local political contexts.

The ACA is largely clinically oriented, and public health was not a primary focus of the legislation. It is, therefore, not surprising that leaders of large, urban health departments are unclear about what clinical services they can and should continue to provide. On the one hand, decreasing clinical care services may lead to a greater focus on population health by their departments; on the other hand, decreasing clinical services may also jeopardize the health of populations that will not be covered by health care insurance, even with the ACA in place. In addition, some participants also acknowledged that if they expand clinical services or seek reimbursements from insurance providers, they may be seen as competitors to local private or other public providers, particularly for patients who were previously uninsured. This shift from a public service to a competitive provider of care may have political implications in some jurisdictions. Beyond the business incentive to provide more clinical services, LHDs planning to increase some of their current direct service offerings or to offer new services (such as behavioral health care) say that they are doing so primarily in response to a priority need in their communities. Addressing persistent need is further complicated for large, urban health departments that often provide services to undocumented immigrants, who will not be covered under the ACA or Medicaid expansion.

Providing clinical care has been a challenge for public health, especially in LHDs, for more than 20 years,14,20–24 and our study supports the fact that these challenges are ongoing. Large LHDs, such as those in the BCHC, tend to provide more clinical services than do those in midsized jurisdictions; the majority of LHDs are discontinuing or planning to discontinue certain types of clinical care—but not uniformly.25,26 In addition, leaders in this study have noted significant opportunity for public health to define its role as a convener, information broker, and analyst in their communities, a sentiment supported by with other research in this area.3,12,13,27

The results of our study also underscore the concern among leaders of large, urban health departments that the ACA could have negative consequences for their jurisdictions. Budget cuts to the federal agencies that provide categorical grant awards may occur as a result of a perception that covered programs and services are no longer needed because of the ACA. If LHDs cannot depend on revenue from clinical services or on funds from local, state, or other federal sources, their ability to fulfill their mission may be compromised. For instance, concern around vaccine shortages or lack of providers in the wake of ACA and new regulation has started to play out in some jurisdictions.28

Limitations

This project had several limitations. First, this was a cross-sectional assessment of a subset of the nation's largest LHDs. Generalizability of the results to all LHDs is, therefore, limited, as the experience and capacity of larger health departments is often quite different from those of medium-sized, small, or rural health departments.4,29 As such, these results should be interpreted only in the context of large, urban health departments. In addition, our results are based on subjective self-reports of participants.

Conclusion

The ACA has helped many public health departments to establish themselves as expert analysts of community data, influencers of policy change, facilitators of community collaboratives, and providers of evidence-based strategies for improving health in communities. Local health departments across the country continue to assess the clinical and population-level needs in their communities and to make important strategic decisions about their evolving role. Leaders see the possibility that the ACA could lead to decreases in or elimination of historically stable grant funding.30 Despite these challenges, however, leaders recognized that the ACA is creating new opportunities to expand their focus on population health and increasing collaborations between public health and health care.

At the time of this study, 18 LHDs constituted the BCHC; 2 have since joined the coalition.

The de Beaumont Foundation and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation funded the Big Cities Health Coalition.

Because data collection for this manuscript focused on key informant interviews from professionals representing their LHDs, because the questions pertained to their professional experiences and professional opinions, and because all information is reported in aggregate or anonymously to preserve confidentiality, IRB submission was not deemed necessary.

The authors thank Elizabeth Rhoades and Philippa Benson for their assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grace Carman K, Eibner C. Changes in health insurance enrollment since 2013. 2014;1:R656. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buck JA. The looming expansion and transformation of public substance abuse treatment under the affordable care act. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(8):1402–1410. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0480; 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koh HK, Sebelius KG. Promoting prevention through the affordable care act. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(14):1296–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Association of County & City Health Officials. National Profile of Local Health Departments. Washington, DC: National Association of County & City Health Officials; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burke T. Federally facilitated insurance exchanges under the affordable care act: implications for public health policy and practice. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(1):94–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stine NW, Chokshi DA. Opportunity in austerity—a common agenda for medicine and public health. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(5):395–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Linde-Feucht S, Coulouris N. Integrating primary care and public health: a strategic priority. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(S3):S310–S311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Plescia M, Richardson LC, Joseph D. New roles for public health in cancer screening. CA: Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(4):217–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoffman S, Guest AP, Leonard W. Public health reform: Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act implications for the public's health: improving health care outcomes through personalized comparisons of treatment effectiveness based on electronic health records. J Law Med Ethics. 2011;39:425–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adashi EY, Geiger HJ, Fine MD. Health care reform and primary care—the growing importance of the community health center. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(22):2047–2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(3):759–769. 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759; 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenbaum S. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: implications for public health policy and practice. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(1):130–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Derksen DJ. The Affordable Care Act: unprecedented opportunities for family physicians and public health. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(5):400–402. 10.1370/afm.1569; 10.1370/afm.1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Institute of Medicine. Committee for the Study of the Future of Public Health. The Future of Public Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beitsch LM, Brooks RG, Menachemi N, Libbey PM. Public health at center stage: new roles, old props. Health Aff (Millwood). 2006;25(4):911–922. 25/4/911 [pii] 10.1377/hlthaff.25.4.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeVille K, Novick L. Swimming upstream? Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and the cultural ascendancy of public health. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2011;17(2):102–109. 10.1097/PHH.0b013e318206b266; 10.1097/PHH.0b013e318206b266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Institute of Medicine. Committee on Integrating Primary Care and Public Health. Primary Care and Public Health: Exploring Integration to Improve Population Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hearne SA. An overview of the BCHC. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2014;21(1):4–13. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Creswell JW, Clark VLP. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Los Angeles, Sage Publications, Inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beitsch LM, Grigg M, Menachemi N, Brooks RG. Roles of local public health agencies within the state public health system. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2006;12(3):232–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gordon RL, Baker EL, Roper WL, Omenn GS. Prevention and the reforming U.S. health care system: changing roles and responsibilities for public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1996;17:489–509. 10.1146/annurev.pu.17.050196.002421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Committee on Public Health Strategies to Improve Health, Institute of Medicine. For the Public's Health: Investing in a Healthier Future. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katz MH. Future of the safety net under health reform. JAMA. 2010;304(6):679–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Institute of Medicine. Committee on Assuring the Health of the Public in the 21st Century. The Future of the Public's Health in the 21st Century. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsuan C, Rodriguez HP. The adoption and discontinuation of clinical services by local health departments. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(1):124–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Etkind P, Gehring R, Ye J, Kitlas A, Pestronk R. Local health departments and billing for clinical services. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2014;20(4):456–458. 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams DR, McClellan MB, Rivlin AM. Beyond the Affordable Care Act: achieving real improvements in Americans' health. Health Aff. 2010;29(8):1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenthal E. The price of prevention: vaccine costs are soaring. The New York Times. July 2, 2014. http://nytimes.com/2014/07/03/health/Vaccine-Costs-Soaring-Paying-Till-It-Hurts.html. Accessed July 9, 2014.

- 29.Harris JK, Mueller NL. Policy activity and policy adoption in rural, suburban, and urban local health departments. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2013;19(2):E1–E8. 10.1097/PHH.0b013e318252ee8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Association of County & City Health Officials. National Profile of Local Health Departments. Washington, DC: National Association of County & City Health Officials; 2011. [Google Scholar]