Abstract

This commentary provides a summary of current efforts and successes with billing for public health services, cites a historical analogy that raises concerns regarding the growth of billing for services, and suggests a parallel course of action.

The Maricopa County Department of Public Health (MCDPH) is vigorously pursuing reimbursement for services via billing of health insurance. Many local health departments (LHDs) have begun on this course of action in response to changes in governmental funding. Yet, paradoxically, our very success to date, especially in billing for immunizations, gives cause for concern. This commentary summarizes current efforts and successes with billing, cites a historical analogy that raises concerns regarding the growth of billing for services, and suggests a parallel course of action.

The Billing Imperative

The system-wide momentum for billing is irresistible. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has prohibited the use of Federal Immunization Grant Program (Section 317) funds for insured children since October 2012.1 It has also awarded $27.5 million to 38 grantees to develop billing for vaccines through its Immunization Billables Project, which specifically aims to increase health department capacity for billing for immunization services.2 The National Association of County & City Health Officials offers more than 260 resources in its Billing for Clinical Services Toolkit3 The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) contains the Essential Community Provider Requirement, which requires all insurance plans sold in the marketplace to include “safety net providers” (LHDs included) as 20% of its in-network provider list.4

As a system, compelled by fiscal realities on the local level and pushed from the federal level, public health agencies are plunging headlong toward billing for all sorts of services. The reasons for doing this are understandable. Public health agencies are in an era of funding cutbacks at all levels, and many people believe this trend will likely persist. Finding a mechanism to sustain core services over time is paramount. Many in public health work in jurisdictions that have been chronically underfunded, and the advent of billing offers a chance to provide what public health should have been doing all along.

More broadly, our residents also live in a culture that accepts billing. At one point in history, there may have been an expectation that certain services were free to all. For a number of years, students received certain vaccines at school for free, for example. Now, some clients express surprise that there is no charge, even for interventions such as treatment for outbreak control.

With implementation of the ACA and increasing coverage of preventive services, governments at all levels are encouraging LHDs to bill for whatever services they can. Our own department is no exception. Pursuing billing for public health services is a perfectly rational course of action.

And yet, it is our own initial relative success that prompts my cautionary tale. Let me relate our experience with billing for one of the most basic, cost-effective, and core of all public health services: immunizations.

Billing for Immunizations in Maricopa County

MCDPH covers an area with a population of more than 4 million people. That makes us the third most populous local public health jurisdiction in the United States, behind only New York City and Los Angeles County. We have 60% of the state's population and are roughly the geographic size of the state of Massachusetts. Although public health departments frequently complain about funding deficiencies, it is worth noting that MCDPH is among the least resourced LHDs for a large jurisdiction in the United States, receiving less than $3 per person per year from local tax revenue.

MCDPH has only 6 immunization nurses and only 3 sites for vaccine delivery amidst our 9224 square miles. Nevertheless, we immunized approximately 50 000 children last year. This achievement is in part due to good fortune; MCDPH is part of an active and effective statewide nonprofit immunization coalition, the Arizona Partnership for Immunization (TAPI). TAPI began working on behalf of LHDs to provide an infrastructure for billing for immunizations in 2008. It took years for TAPI to navigate the system, establish a process for billing, and negotiate contracts with insurers. TAPI began with the Medicaid plans in our entirely managed care Medicaid system, the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System (AHCCCS), and established a mechanism for billing for only the administration costs associated with vaccines, since children covered by AHCCCS are eligible for Vaccines for Children vaccine.

Reimbursements from AHCCCS plan to cover administration costs began to arrive in 2010. An entirely new process of negotiating contracts with private insurance plans soon followed, requiring negotiation of reimbursement rates and contract agreements as well as the creation of an infrastructure to handle claims. Purchasing MCDPH's own supply of private stock vaccines followed, and billing of private insurance began in 2012. On behalf of MCDPH and most other local public health departments in Arizona, TAPI now contracts with the 6 largest insurers, which together cover more than 80% of Arizona's privately insured population.

In calendar year 2013, TAPI collected $2252 960 from private insurers statewide for vaccines. Even with the administrative overhead that TAPI must keep to maintain billing, MCDPH is coming out modestly ahead. During fiscal year 2013 (the first partial year of billing), MCDPH spent $301 682 to purchase vaccines and received $366 688 in reimbursements, giving us $65 000 to support the program that we did not have before. We have a net gain of 21.5% over our vaccine supply expenses, although this does not include staff time and related costs, which are, of course, considerable.

Sounds OK, right? Excluding personnel expenses, MCDPH is creating a stable system that can persist despite funding cuts at the state and federal levels. And whatever funds are brought in beyond the administrative overhead needed for billing are resources that the program did not have previously. This is all perfectly rational. Yet sometimes, courses of action that are perfectly rational, and, indeed, imperative in the short term, can be disastrous in the long run.

The Analogy of US Health Care Financing

Consider the analogy of billing within the American health care system. The seeds were sown in the 1930s and 1940s for the complex employment-based health insurance system in the United States. The rapid expanse of labor unions that occurred during the depression ran smack into the national wage freeze of World War II. Without wages as an issue for contract negotiations, unions needed to maintain their relevance. They sought, and were granted, the ability to negotiate benefits outside of the wage freeze.5

By negotiating for benefits, including health insurance, unions were happy to demonstrate meaning to their membership, employers were happy to provide a then-inexpensive benefit in lieu of higher payroll costs, employees were happy to receive the health care coverage, and politicians were happy to please their constituents without risking the potentially ruinous consequences of labor unrest during the war effort. Other rulings followed to reinforce this trend.5

It was a perfectly rational course of action.

The trouble is that this rational course of action ultimately led, in part, to the incredibly inefficient US health care system. The United States left a huge portion of the population uncovered; has experienced increasingly burdensome costs, which now total approximately 18% of the Gross National Product (half again as much as the next closest industrialized country6); and has shown mediocre outcomes at best on most important health measures.7

Much of the expense is inherent in the process of billing individual insurance plans for individual services provided to insured individuals. The administrative costs of the health care system stand at approximately one-fourth of total health care spending, much higher than those of any other country.8

The Point of Immunizations

Now return to the concept of immunizations as a public health service. Are they just another type of health care for individuals?

No vaccine is perfect. Yet, many formerly common diseases are now quite rare due to herd immunity. Simply put, by keeping the rate of immunity high in the entire population, the odds decrease that a single individual's germs can find a susceptible person to infect. When the level of immunity reaches the point that there is less than 1 new infection per original case of disease, then outbreaks become unsustainable. Thus, whether an individual's personal vaccine succeeds in protection no longer matters—because one never gets exposed in the first place.

The success of herd immunity transforms vaccines from an individual health measure into a communal benefit. In other words, whether your neighbor is immunized matters to your health. There is a social imperative to keep immunization levels high.

Is society risking herd immunity by billing for vaccines? At first blush, one might argue not. The ACA requires first dollar coverage of immunizations, without a deductible or co-pay, so what's the harm in billing insurance for vaccines? Furthermore, billing insurance carriers seems only right, since insurance premiums are already paid—by individuals, by employers, and by government—to include coverage of vaccines. This rationale fits nicely within a cultural expectation of billing for services. And as for the bottom line, in MCDPH's early experience, it is even covering the cost of vaccines.

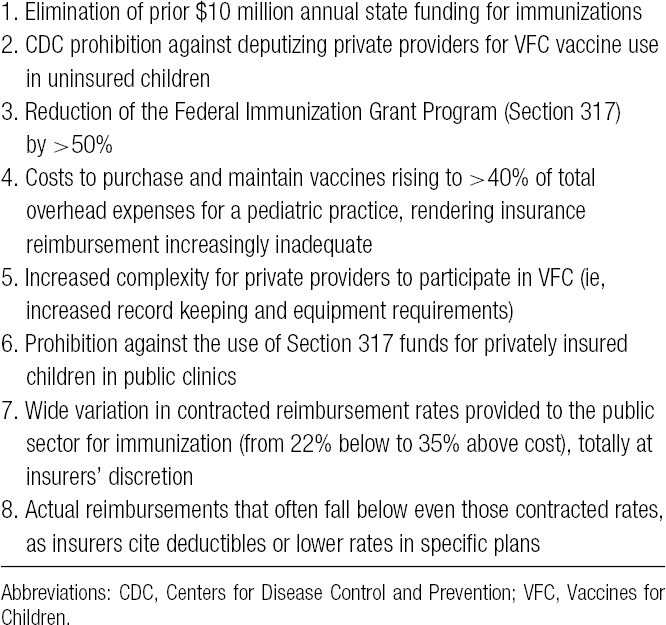

So how could this possibly risk the communal benefit of herd immunity? In a nutshell, because of continuous flux in the system, unintended consequences are inevitable. The Table illustrates that flux with examples of developments over the past few years in Arizona.9

TABLE •. Developments Impacting Community Immunization Status in Arizona, 2009-2014.

These developments have placed further pressure on the private sector, resulting in increased rates of providers referring even fully insured patients to public clinics for some or all vaccines (already at 50% of providers polled).10 Aside from creating an additional step and a hurdle for obtaining immunizations, this further discourages patients from maintaining an active relationship with their medical home, as parents take their children directly to public health sites for immunizations when next needed. Presently, approximately 10% of MCDPH immunization recipients are privately insured.

In turn, this shifts costs to local governments, which many elected officials are unwilling to bear, which in turn forces some LHDs to turn patients away. Meanwhile, individuals who are receiving vaccines in providers' offices and are currently within their insurance deductibles are forced to choose between paying out-of-pocket for very expensive vaccines and forgoing them, sometimes choosing the latter.

A pattern of back-and-forth referral between private and public clinics is emerging, with some patients being turned away from some settings or facing significant obstacles to receiving vaccines, which ultimately may lead to decreased immunization rates, loss of herd immunity, and the threat of outbreaks.

There appears to be a common perception that the ACA has already solved all of this, despite the fact that (a) “first dollar coverage” does not affect the actual reimbursement rate (which is often less that the cost); and (b) that an estimated 65% of current privately insured individuals in Arizona are in grandfathered/self-insured plans that will be unaffected by the vaccine requirements of the ACA.9

All of this is occurring against a backdrop of gradually increasing vaccine exemption rates in schools, as more and more parents choose not to immunize. Some may actually be influenced to do so by extra hurdles in obtaining vaccines from private providers, such as waiting for an appointment only to be referred elsewhere for particular vaccines the provider chooses not to offer. Arizona allows parents to choose exemption based upon personal belief (which often translates to simple preference), in addition to medical or religious exemption.

In addition, it must be noted that billing service-by-service, client-by-client, insurance company-by-company, particular plan-by-plan, adds significant administrative overhead. Again, MCDPH is fortunate that TAPI, as a nonprofit partner agency, adds no profit margin to these overhead costs. Nevertheless, TAPI must currently retain approximately 20% of total reimbursement received to cover its costs. This does not include MCDPH's own personnel costs for the time needed to collect insurance information, record and code the vaccines provided, and submit it all for the more than 20 000 insured children (counting both AHCCCS and private insurance) that we immunized last year.

Billing based upon individual recipients and services is the hallmark of American health care financing. Yet, it is primarily responsible for the incredible administrative overhead of the entire system. This is inarguably the most administratively expensive way to fund anything.

Does it make any sense to choose such a method to fund a communal benefit?

Of course, the private health care system has long been forced to bill for individual vaccines. America treats immunizations as an individual health care commodity, to be sold the same way as any other health care service. Why should it make any difference to add public health to that same billing system?

Public perception, combined with continuous flux in the system, makes unintended consequences inevitable. Most elected officials and even many public administrators do not grasp the concept of “herd immunity.” The more that vaccines are treated as a commodity—even if expenses are covered by billing in the short run—the more public health risks reinforcing the notion that vaccines are an individual choice, rather than a societal measure. The more we get away from the concept of communal benefit, the more policies may evolve that endanger herd immunity.

In Arizona, state elected officials have already chosen to not fill any funding gaps for vaccines. The state already allows parents to exempt their children from school vaccine requirements as a simple matter of choice. The legislature has already set the precedent of precluding certain vaccines from ever being a school requirement, starting with human papillomavirus vaccine.11 Meanwhile, officials have trimmed immunization funding, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has given clear direction that we must bill for the vaccines we provide to insured individuals.

The Implications

Again, in the short run, in the context of the US health care system, billing for public health services such as immunizations makes sense, much as encouraging employer-based health insurance made sense in the 1940s. But what consequences might the future hold?

Right now, MCDPH turns no one away from immunization clinics, even if the recommended vaccine he or she seeks is not covered by insurance. Perhaps your LHD does the same. (Remember, many individuals are insured by “grandfathered” plans, not subject to ACA coverage requirements.) And MCDPH is not yet losing money on the actual cost of vaccines, excluding personnel costs. Will that always be the case?

Might not the elected or managerial leadership someday force health departments to pay for immunization-related personnel out of reimbursement? Might not the cost of vaccines continue to rise? Of note, the cost to vaccinate each child, through 18 years of age, with all ACIP-recommended vaccines has ballooned from $70 in 1990 to $1712 in 2012, at federal contract prices. That is a 24-fold increase over 22 years.12

Would not either of those events force us to turn clients away for uncovered vaccines? What other unforeseen changes in the system will impact immunizations?

Will my successor feel the same as I do about never turning a client away? Will the next leader of your LHD? Might they not turn away those who are uninsured or attempt to collect from individuals if insurers fail to reimburse? What effect will that have on herd immunity? The further we slip away from funding communal benefits via some sort of single payer or global budget model, the more we risk losing those benefits on a societal level.

Now apply the same principles to other public health services. Desperate to maintain or expand core functions, public health is in the early stages of exploring billing for all manner of services.

Many of these are arguably individual health care services, although some provide a demonstrably positive return on investment to society. Examples include various home visitation services, nutrition counseling, and chronic disease self-management training.

On the contrary, some services for which we are exploring billing fall squarely in the communal benefit category, just like immunizations. Examples include sexually transmitted disease and tuberculosis clinic services. These clinics exist not to provide optional, personal care but as efficient adjuncts to communicable disease control programs for these particular conditions. They may appear to be personal health care, but they are part of the communal benefit of keeping those diseases from spreading. If billing for these creates a perceived hurdle and discourages persons from seeking care, third parties are placed at risk, and the cost of containing the disease after it has spread further is higher.

Other disease intervention services are under consideration as well. If one could contract with insurers as a specialty service, perhaps all communicable disease reporting might be considered provision of a “provider referral.” Could public health then bill insurance plans for testing, counseling, and treatment related to reportable disease interventions as “specialty care” resulting from that provider referral? Once this is in place and time has passed, does public health risk elected or appointed leaders eliminating other funding sources for classic disease control programs or telling public health that we must decline to intervene for uninsured individuals or must bill clients for uncovered claims?

The Plea

I'm not saying public health should not bill. Given this time in history, funding imperatives, and societal expectations, there is no way out of it. Billing promises to backfill much of the revenue losses of the recent past and even to expand services by adding funding that we never had. Public health will help a lot of people with the revenue generated through billing.

However, public health should also recognize that this is a course toward the least efficient mechanism of funding possible, and future battles to defend serving those who lack a payment mechanism will follow. So while these billing systems are built, public health had better be simultaneously building arguments for the communal benefits accrued by essential public health services and the positive returns on investment realized by some other personal preventive services. And public health had better be strategizing how to make this understandable to the public and to decision makers.

If we do not, our successors will view us the same way we view those who, in the 1940s, set in motion the future of the US health care system with which we still struggle.

Footnotes

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Questions & answers about vaccines purchased with 317 funds webpage. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/guides-pubs/qa-317-funds.html Published 2013. Accessed April 27, 2014.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Immunization Billables Project. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/billables-project/billing.html. Accessed April 27, 2014.

- 3.National Association of County & City Health Officials. http://www.naccho.org/toolbox. Accessed April 27, 2014.

- 4.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Frequently Asked Questions on essential community providers. http://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Fact-Sheets-and-FAQs/Downloads/ecp-faq-20130513.pdf. Accessed April 27, 2014.

- 5.Blumenthal D. Employer-sponsored health insurance in the United States—origins and implications. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(1):82–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The World Bank. Health expenditure, total (% of GDP). http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.TOTL.ZS. Accessed April 27, 2014.

- 7.Davis K, Schoen C, Stremikis K. Mirror Mirror on the Wall: How the Performance of the US Health Care System Compares Internationally, 2010 Update. New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund; 2010. http://www.commonwealthfund.org/∼/media/Files/Publications/Fund%20Report/2010/Jun/1400_Davis_Mirror_Mirror_on_the_wall_2010.pdf. Accessed April 27, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Why does health care cost so much in America? PBS Newshour. November 19, 2013. http://www.pbs.org/newshour/rundown/why-does-health-care-cost-so-much-in-america-ask-harvards-david-cutler. Accessed April 27, 2014.

- 9.The Arizona Partnership for Immunization. Arizona vaccine delivery system & issues: an overview and history. In: CDC Billables Project. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tinney J. Keeping kids strong through The Arizona Partnership for Immunization. NACCHO Exchange. 2013;12(3):17–18. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arizona Revised Statutes 36-672(C).

- 12.Schuchat A. Vaccine management. Vaccination News. http://www.vaccinationnews.com/sites/default/files/CostofVaccinesfromBirthtoEighteen.pdf. Accessed April 27, 2014.