Abstract

Resilient readers are those who, despite their poor phonological decoding skills, have good comprehension abilities (Jackson & Doellinger, 2002). Thus far, these readers have been identified in college settings. The purpose of this study was to a) determine if this reader profile was present in a sample taken from an Adult Basic Education (ABE) population, and b) identify compensatory mechanisms these readers might use to better their reading comprehension. We administered a battery of tasks consisting of non-word reading, comprehension, fluency, and orthographic processing to a diverse sample of adults in ABE classes. Not only did we identify a group of resilient readers in this sample, we identified three other sub-groups: unskilled readers who had poor decoding and comprehension abilities, skilled readers who possessed good decoding and comprehension abilities, and a group of individuals who had good decoding skills but poor comprehension abilities. We found that the resilient readers and good decoders/poor comprehenders had better orthographic and fluency skills compared to the unskilled readers. However, these last two groups produced different error patterns on the orthographic and fluency tasks. We discuss the implications that these very different reader profiles have for ABE programs.

Typically, less skilled readers are characterized by their poor decoding skills, which is the ability to apply letter-sound correspondences to pronounce words. As a result of poor decoding, their comprehension abilities suffer as well. That is, if a reader is devoting considerable resources to sounding out and identifying individual words, few resources are left over to string those words together to form a meaningful, coherent representation of the text. Recent research, however, has identified a segment of the unskilled reader population that deviates from that typical pattern. Jackson and Doellinger (2002) identified a small group of college readers, approximately 3% of their sample, who—despite their poor decoding abilities—had average comprehension abilities. They named these individuals “resilient readers.” This study found that resilient readers’ performance on non-word reading, which is a typical measure of decoding, was well below average (z scores of less than −1.00), but their comprehension performance was much better (z scores of 0 or above) than their decoding abilities.

Researchers hoping to identify resilient readers typically administer a non-word reading task to assess decoding skills. In such a task, a participant might be asked to pronounce letter strings like “saist” or “rox.” A reader with poor decoding skills will struggle to link letters with sounds to perform this task and would, consequently, be identified as a poor decoder. Comprehension is also measured in these studies. To assess comprehension, a participant might be asked to fill in the blank with the appropriate word to complete a sentence or short passage, as they do in the Passage Comprehension subtest of the Woodcock-Johnson III Test of Achievement (Woodcock, McGrew, & Mather, 2001). Resilient readers perform better on this task relative to their non-word reading performance. Thus, while resilient readers may have difficulty with decoding and recognizing words in isolation, they are able to comprehend material, perhaps by relying on the context of some of the words they are able to identify.

Clearly resilient readers have developed skills to compensate for their poor decoding abilities in order to comprehend reading material. This has led researchers to investigate the compensatory mechanisms these readers use. Jackson and Doellinger (2002) compared their resilient readers to two groups: poor readers who were below average on both decoding and comprehension and good readers who had decoding and comprehension abilities expected of a college sample. They assessed readers on spelling, speeded reading, verbal intelligence, listening comprehension, and working memory abilities. Verbal intelligence was assessed using the Vocabulary (e.g., “What is a guitar?”), Similarities (e.g., “In what way are an apple and pear alike?”), and Information (e.g., “Who is the president of Russia?”) subtests from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS III). To measure listening comprehension, participants listened to two different passages and then answered several questions about each passage. Working memory was assessed using a reading span task in which participants had to read an increasing number of sentences while remembering the last word in each sentence. In addition to poor decoding skills, resilient readers and poor readers were deficient on spelling and speeded reading compared to good readers. Additionally, resilient readers did not appear to have superior verbal intelligence, listening comprehension, or working memory spans; thus, these researchers were unable to identify any special compensations resilient readers use.

Welcome, Leonard, and Chiarello (2010) investigated the possibility of orthographic (i.e., spelling patterns) and/or semantic (i.e., meanings and relationships among words) abilities as the source of potential compensations. Welcome et al. compared resilient readers to poor readers and good readers. Both resilient and poor readers had Word Attack scores (i.e., decoding skills) that fell below the 35th percentile. Resilient readers had Passage Comprehension scores above the 45th percentile. Participants who scored above the 45th percentile on both tasks were classified as good readers. Approximately 10% of Welcome et al.’s sample was classified as resilient readers. Orthographic abilities were assessed using an orthographic choice task in which participants had to select the correct spelling from a pair of words. Semantic abilities were assessed with a semantic priming task, in which a prime was either semantically related (e.g., doctor – nurse) or unrelated to a target word (e.g., bread – nurse). While Welcome et al. found that resilient readers did not possess superior orthographic abilities, resilient readers did display an enhanced semantic priming effect compared to both good and poor readers. That is, resilient readers benefitted more when the prime was semantically related to the target word compared to when no such semantic relationship existed between the pair of words. Thus, Welcome et al. concluded that semantic abilities might be the compensatory mechanism these readers use to enhance their comprehension skills.

Thus far, resilient readers have only been identified among samples of college students. The current investigation sought to identify whether resilient readers would be present in a sample of adults with low literacy skills. As outlined above, resilient readers have an uneven profile of performance across component skills of reading. Several studies have demonstrated that adults with low literacy skills also have uneven reading profiles. For example, Greenberg, Ehri, and Perin (1997; 2002) found that adults with low literacy skills had relative strengths in orthographic abilities compared to phonological abilities. That is, the adults outperformed children when they read irregularly spelled words (e.g., ocean, iron) and when they had to select which non-word looked more like a word (e.g., filv vs. filk). However, children were better than adults on phonological tasks: reading non-words (e.g., raff, shab), deleting phonemes from a word (e.g., “Say ‘smile’ without the ‘s’.”), and segmenting phonemes (e.g., How many sounds are in the word ‘see’?”). Thompkins and Binder (2003) found similar results, but they also found that adults outperformed children matched on reading grade level in memory abilities and the use of context. Furthermore, it is commonly assumed that adults with low literacy skills develop sophisticated strategies for circumventing their deficits. There is evidence that some struggling adult readers can use contextual cues to improve comprehension more effectively than children at similar reading levels. For example, Blalock (1981) observed that adults with low literacy skills could read many words in context that they could not read in isolation. Read and Ruyter’s (1985) adult literacy participants’ comprehension scores over-predicted their decoding skills, suggesting that they were able to use context to effectively mask their deficits in word decoding. Binder, Chace, and Manning (2007) examined how sentential contexts were used by adults with low literacy skills compared with skilled adult readers. In one experiment, participants read sentence contexts that were congruent (e.g., The cat chased the mouse.), incongruent (e.g., The cop chased the mouse.), or neutral (e.g., The guy chased the mouse.) with respect to a target word they had to read out loud. Both skilled and less skilled adults benefitted from a congruent context and were not disadvantaged by an incongruent context. Contrary to research conducted on children learning to read, skill level of the adult reader did not interact with context. This suggests that beginning readers, adults and children, may differentially rely on context.

To reiterate, the purpose of the current study was to investigate the existence of resilient readers in a sample of adults with low literacy skills. We administered the Word Attack and Passage Comprehension subtests from the Woodcock-Johnson III Test of Achievement (Woodcock et al., 2001) in order to identify different groups of readers using criteria from Welcome et al. (2010). Thus, our first goal was to get a sense of the prevalence of resilient readers in this population. Given that adults with low literacy skills have been found to have uneven reading profiles (e.g., Greenberg et al., 1997, 2002; Thompkins & Binder, 2003), we expected that we would find resilient readers in our sample. The second goal was to examine some of the potential compensatory mechanisms that resilient readers might use to overcome their poor decoding abilities. We examined orthographic and semantic abilities as potential compensatory mechanisms. For the orthographic task, we had participants read a list of irregularly spelled words (e.g., island, ocean). While past studies of college students did not find that orthographic abilities were used as a compensatory mechanism, we believed adults with low literacy skills might exploit this information in reading since other studies have found that orthographic ability is a relative strength in this population (Greenberg et al., 1997, 2002; Thompkins & Binder, 2003). For the semantic task, we had participants read a passage and then measured their fluency as well as the types of errors they made while reading. We expected that resilient readers might show strength in using contextual information while reading compared to the other groups.

Method

Participants

Most resilient readers have been identified through samples of college students. These students have presumably had access to academic resources not available to adults with low literacy skills and thus perform at or above the expected grade-level on most literacy assessments. Adults with low literacy skills, on the other hand, tend to demonstrate lower scores on many of these assessments. The participants for this study were drawn from a previous sample of 90 Adult Basic Education (ABE) students1. All of the students were enrolled in community-based literacy programs in western Massachusetts. All of the programs from which participants were obtained had both ABE and English Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) courses. Participants were selected from ABE classes of which 44 were native speakers of English and 46 were non-native speakers of English. The mean reading grade level of our participants was 5.1 (median = 4.4). The mean age of the participants was 34 years old (range: 18 to 64). Eleven of the non-native participants indicated that they could not read a newspaper in their native language. The racial background of the sample was varied: 44 individuals of Hispanic background, 29 African American, 13 Caucasian, and 4 Asian. The ages, racial/ethnic backgrounds, and skill levels of this sample are representative of the population of adults who are enrolled in ABE classes in Massachusetts.

In order to investigate the pattern of performance among readers, four groups were created based upon each student’s scores on the Word Attack (WA) and Passage Comprehension (PC) subtests from the Woodcock-Johnson III Test of Achievement (Woodcock et al., 2001) using the criteria established by Welcome et al. (2010). First, percentile rank scores relative to the sample of both subtests were calculated. Students who scored below the 35th percentile on the WA subtest were identified as unskilled decoders, while students who scored above the 65th percentile were identified as skilled decoders. Next, students who scored below the 50th percentile on the PC subtest were identified as below average or unskilled comprehenders relative to the group, while students who scored above 50th percentile on the subtest were identified as average or skilled comprehenders, relative to the group. Our cut-off scores mirrored those of Welcome et al. (2010) with similar justification. By implementing conservative percentiles on the decoding task, we are able to identify and analyze the readers with marked decoding deficits or proficiency relative to our sample. On the other hand, using a less conservative cut-off point for the comprehension task enabled us to capture readers from our sample who were comprehending text at least at the average skill level relative to our group. Our intention was to identify and examine four distinct groups of readers within our sample: (1) skilled readers who performed above the cutoff scores on both tests, (2) unskilled readers who performed below the cutoff scores on both tests, (3) resilient readers who performed below the 35th percentile on WA but above the 50th percentile on PC, and (4) skilled decoders/poor comprehenders who performed above the 65th percentile on WA but below the 50th percentile on PC. Importantly, there was a dissociation between decoding and comprehension abilities for two of our groups: resilient readers and good decoders/poor comprehenders. On average, the difference in percentile scores between decoding and comprehension was 47 points for resilient readers and 50 points for good decoders/poor comprehenders. Thus, these two groups had very different performances on these measures.

Materials

In order to assess reading proficiency and identify groups of readers, the following tests were administered:

First, four subtests of the Woodcock-Johnson III Test of Achievement (Woodcock et al., 2001) were used for the purposes of the current study. These tests were Word Attack, Passage Comprehension, Reading Fluency, and Letter-Word Identification. Standard administration and scoring procedures were used unless otherwise noted.

Word Attack (WA)

In this subtest, participants were asked to pronounce a series of non-words (e.g., ib, yosh). The test is designed such that the complexity of the non-words becomes increasingly difficult. Testing was discontinued when the participant gave six incorrect answers.

Passage Comprehension (PC)

Participants were asked to read sentences with a missing word. Their task was to provide the missing word that completed each sentence. For example, “The drums were pounding in the distance. We could _____ them”. Participants were asked to supply the correct answer, “hear”. The test increases in level of difficulty. Testing was discontinued when the participant gave six incorrect answers.

Reading Fluency (RF)

Participants were asked to read statements and determine if each statement was true or false. For example, an item could be, “Fish live on land.” Testing was discontinued after three minutes.

Letter-Word Identification (LWI)

Participants were asked to read letters and words in increasing difficulty. The task was presented on flashcards. Testing was discontinued when the participant gave six incorrect responses.

Two subtests from the Dynamic Indicators of Basic Literacy Skills (DIBELS; Good & Kaminski, 2002) were used in this study. They were:

DIBELS Non-word Fluency task (NWF)

The participants were provided with a sheet of paper that included a number of vowel-consonant (e.g., ov) or consonant-vowel-consonant (e.g., sig, rav) non-words. Participants were asked to read as many non-words as they could in one minute.

DIBELS Oral Reading Fluency (ORF)

Participants were asked to read a passage aloud for one minute while the examiner recorded the words read correctly per minute (WRCM). If a student hesitated for three seconds, the examiner provided the word. Correctly read words were defined as words read correctly the first time or subsequently self-corrected. Words read incorrectly were words that were mispronounced, skipped, substituted, or hesitated on for three seconds. The passage used in the current study was calibrated at a third grade level of difficulty based upon Spache readability measures (Good & Kaminski, 2002).

Irregular Word Reading (IWR)

In order to assess orthographic abilities, we had participants read irregularly spelled words. This measure was adapted from Adams and Huggins (1985). The participant was given a list of 50 irregularly spelled words, in order of lowest to highest frequency, according to Francis and Kucera norms (1982) and asked to read them aloud. Examples include: ocean, deaf, and yacht. The number of words read correctly out of the total number of words served as the dependent measure. Testing was discontinued when the participant read 10 consecutive words incorrectly.

Procedure

The tests listed above constituted a portion of the tests that were given in the full study (Binder et al., 2011). Tests were administered in two 15–20 minute sessions. On the first test administration day, informed consent was obtained, and participants completed a brief oral demographic survey and then were given the four Woodcock-Johnson measures. On the second day of test administration, participants were asked to complete the DIBELS measures and read the irregular word list.

Results

Using the criteria we outlined in the Method section, we identified four reading groups: (1) skilled readers who had both good decoding and comprehension skills (n = 25), (2) unskilled readers who had poor decoding and comprehension skills (n = 18), (3) resilient readers who were poor decoders but had average comprehension skills (n = 14), and (4) good decoders who had poor comprehension skills (n = 12). We should note that previous studies investigating resilient readers have compared this group to unskilled and skilled readers. Our investigation included a fourth group – good decoders with poor comprehension skills. We will write more about the characteristics of these participants in the Discussion section.

For each of our measures, we conducted a one-way ANOVA in which the reading group was the between groups factor. Each significant main effect was followed by Tukey’s post hoc analyses. See Table 1 for means and standard deviations for all measures. For WA, there was a significant difference among the four reading groups, F(3,65) = 305.1, MSe = 7.3, p < .0001, ηp2 = .934. While there was no difference in the decoding skills of unskilled and resilient readers, these two groups scored lower than the good decoders/poor comprehenders and skilled readers. These latter two groups did not differ from one another.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations for each of the Measures by Reading Group.

| Measure | Unskilled Readers | Resilient Readers | Good Decoders/Poor Comprenders | Skilled Reader |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work Attack | 7.28a (3.18) | 7.93a (2.37) | 26.83b (3.10) | 27.56b (2.30) |

| Passage Comprehension | 18.56a (4.25) | 28.79b (2.61) | 21.75c (2.14) | 32.32d (2.87) |

| Letter Word Identification | 39.28a (8.46) | 46.50b (6.86) | 57.42c (10.82) | 64.36d (4.78) |

| Nonsense Word Fluency | 39.50a (30.39) | 52.57a (34.48) | 91.62b (46.98) | 104.48b (42.34) |

| Oral Reading Fluency | 74.44a (40.85) | 122.86b (36.13) | 132.17b (49.27) | 172.96c (30.62) |

| Reading Fluency | 23.67a (11.95) | 39.43b (14.68) | 36.33b (12.20) | 52.52c (11.86) |

| Irregular Word Reading | 12.5a (9.10) | 27.14b (11.13) | 25.08b (9.68) | 39.44c (9.15) |

Note: When a significant main effect for group was found, superscripts were added to indicate which groups were different from one another. Groups with the same superscript did not differ significantly from one another.

For PC, there was a significant main effect of reader group, F(3,65) = 78.2, MSe = 9.9, p < .0001, ηp2 = .783. There were significant differences among all groups with the unskilled readers performing the worst, followed by the good decoders/poor comprehenders, then the resilient readers, and the skilled readers displaying the best comprehension skills (all ps < .05).

We used WA and PC to establish our groups, but we wanted to make sure the pattern of differences in decoding and reading behavior would be found if we used other tasks. Therefore, we ran additional analyses: the Nonsense Word Fluency subtest from the DIBELS and Letter Word Identification from the Woodcock-Johnson were used as additional decoding/word recognition variables, and the Oral Reading Fluency subtest from DIBELS and Reading Fluency from the Woodcock-Johnson were used as reading measures. Finally, in order to assess whether there were differences across groups in orthographic processing, we also examined performance on Irregular Word Reading.

Decoding/Word Recognition Measures

For Nonsense Word Fluency, there were significant performance differences across groups, F(3,64) = 12.1, MSe = 1504, p < .0001, ηp2 = .361. Unskilled readers and resilient readers performed similarly, and their performance was worse than the good decoders/poor comprehenders and the skilled readers, whose performance did not differ from one another. For Letter Word Identification, there were also significant group differences, but the pattern was different, F(3,65) = 44.0, MSe = 56.4, p < .0001, ηp2 = .670. Unskilled readers had the poorest performance, followed by resilient readers and then good decoder/poor comprehenders; skilled readers performed the best. All differences were significant (ps < .05). The difference in performance across these tasks could be that real words, not non-words, are used in the Letter Word Identification task compared to Nonsense Word Fluency. Thus, the better performance of resilient readers compared to unskilled readers may be due to better orthographic and/or semantic abilities.

Reading Measures

There were significant group differences for both Oral Reading Fluency and Reading Fluency, and the pattern of the differences was the same for both of these measures, F(3,65) = 23.5, MSe = 1454.7, p < .0001, ηp2 = .520; F(3,65) = 18.8, MSe = 157.6, p < .0001, ηp2 = .464, respectively. Poor readers had the worst performance on these two tasks, followed by resilient readers and good decoders/poor comprehenders, whose performance was not different from one another, and skilled readers performed the best on these two tasks. It was surprising that the resilient readers and good decoders/poor comprehenders performed similarly on these two tasks. To better understand this finding, we performed an error analysis on the Oral Reading Fluency task, and we classified the type of errors that readers made while reading. The errors fit into one of the following six categories: omissions, insertions, deletion of a morphological ending (e.g., leaving off the –ed from a past tense verb), adding a morpheme (e.g., adding an –s to pluralize a noun when the noun was singular), verb tense problems, and confusing closed class words (e.g., reading “the” when “a” was in the text). While all readers made more omissions and morphological deletion errors than other categories of errors F(5,325) = 24.91, MSe = .74, p < .0001), ηp2 = .277, there were not interesting differences in error patterns across groups. However, an interesting pattern of errors across groups did emerge when we examined the types of substitutions readers made. The substitutions could be categorized as either a phonological substitution (sounded like the word in the text), an orthographic substitution (looked like the word in the text), or a semantic substitution (the word made sense in the context of the text). First, skilled readers made no substitution errors, while unskilled readers made a mix of phonological, orthographic, and semantic errors. Good decoders/poor comprehenders made semantic and orthographic errors, while resilient readers only made semantic substitutions.

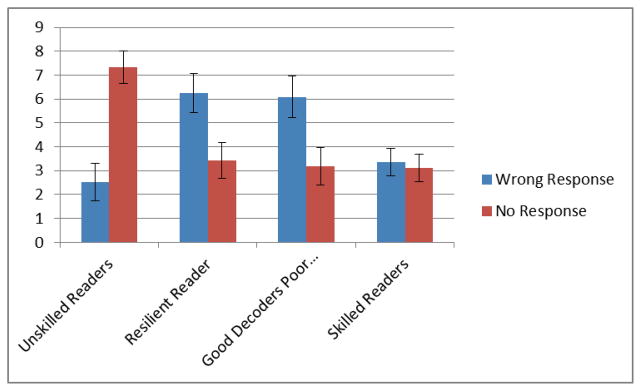

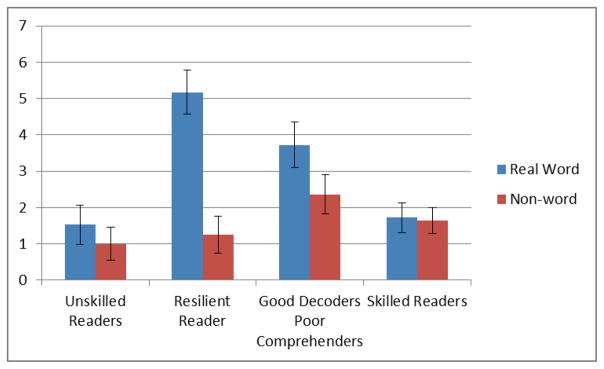

Orthographic measure

There were group differences on Irregular Word Reading, too, F(3,65) = 27.5, MSe = 93.1, p < .0001, ηp2 = .559. Once again, unskilled readers had the worst performance, followed by resilient readers and good decoders/poor comprehenders, whose performance was not different from one another; skilled readers performed the best. Again, we wanted to understand why resilient readers and good decoders/poor comprehenders earned comparable scores. Thus, we conducted another error analysis. For this task, when a participant got an item wrong, it was wrong either because they did not make a response or they produced an incorrect response. For the first analysis, we compared the number of ‘no’ responses to the number of incorrect responses for each participant. For the second analysis, we categorized the incorrect responses into non-word responses (e.g., deef instead of deaf) and real-word responses (e.g., really instead of rely). We conducted two ANOVAs in which the type of error was a repeated measure and group was a between subjects variable. For the first analysis, there was a significant interaction, F(3,59) = 7.20, MSe = 12.42, p < .0001, ηp2 = .243. See Figure 1 for means and standard errors. Unskilled readers had significantly more ‘no’ responses than wrong responses. Skilled readers did not differ in the number of ‘no’ responses and wrong responses. Interestingly, both resilient readers and good decoders/poor comprehenders had significantly more wrong responses than ‘no’ responses. Thus, at least compared to unskilled readers, resilient readers and good decoders/poor comprehenders try harder at the task. Next, we wanted to examine the wrong responses that were generated. When a participant gave a wrong response, that wrong response could have been a real word or a non-word. Once again we ran a 2 (error type) × 4 (reader group) mixed ANOVA and found a significant interaction, F(3,59) = 5.97, MSe = 3.53, p < .001, ηp2 = .256. See Figure 2 for means and standard errors. Resilient readers gave more real word responses than non-word responses. No other differences were significant. From these results we can infer that resilient readers attempt more problems, and when they do attempt difficult items, they use their semantic knowledge to come up with a real word.

Figure 1.

Means and standard error bars for types of errors across groups for irregular word reading.

Figure 2.

Mean (standard error) error type for the irregular word reading task when a wrong response was made to name the word.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was two-fold. First, we wished to identify resilient readers within a sample of adults with low literacy skills. Second, we sought to identify the compensatory mechanisms these readers use in the service of reading comprehension. We identified four distinct groups of readers within our adult sample: readers who had good decoding and comprehension abilities, readers who had poor decoding and comprehension abilities, resilient readers whose decoding skills were poor but whose comprehension abilities were average, and finally, good decoders who had poor comprehension abilities. Second, while these groups differed on non-word reading and comprehension, they also differed on orthographic processing and reading fluency. This highlights the importance of assessing multiple components of reading skill as adults with low literacy skills differ in their reading ability.

Not only did we find that resilient readers exist among adults with low literacy skills, the base rate in this population seems to be greater than what is found in samples of college students. For example, Jackson and Doellinger (2002) found that resilient readers comprised 3% of their sample, while 14% of our sample was classified as resilient readers. The difference between these rates could be due to a larger base rate of skilled readers in the college sample.2 In addition to resilient readers, we also found a group of readers who were good decoders but had poor comprehension skills. In an attempt to know more about who these good decoders but poor comprehenders were, we explored our demographic variables for more information. Interestingly, in this group of 12 individuals, all but one were non-native English speakers and all of the non-native speakers indicated they were print literate in their native language. This finding is akin to the ESL readers identified by Strucker, Yamamoto and Kirsh (2007). They identified different classes of readers among ABE and ESL groups, including a group of poor decoders with stronger vocabulary scores and several groups of ESL learners who demonstrate decoding skills superior to their vocabulary skills. However, it is important to point out that while Strucker et al. found differences in vocabulary skills, the present study identified asymmetrical trajectories in students’ reading comprehension skills in comparison to decoding skills. In both the previous and present research, it appears that second language learners were using the skills they had developed in their native language to help decode words but still had difficulty putting the words together to form a coherent representation of what they read in order to comprehend the material. Interestingly, research has also identified a similar pattern among children. These so-called “word callers” demonstrate effective decoding skills but do not sufficiently comprehend the text they read (Stanovich, 1986).

Researchers have tried to identify the compensatory mechanisms resilient readers use. We found that resilient readers had better orthographic abilities compared to poor readers. This conflicts with the findings of Welcome et al. (2010), who found that resilient readers did not differ from poor readers on measures of orthographic processing. However, our finding is consistent with past research conducted with adults with low literacy skills. Greenberg et al. (1997, 2002) and Thompkins and Binder (2003) found that orthographic skills were a relative strength for adults with low literacy skills compared to children matched on reading grade level. Thus, using orthographic abilities as a compensatory strategy might be one way these readers differ from the resilient readers in the college population. Interestingly, the error analysis on this task demonstrated that, when resilient readers made an error, their error was more likely to be a real word substitution error than a non-word. This pattern was unique for this group.

Welcome et al. (2010) did find that resilient readers used semantic information more efficiently than poor or good readers. In our study, we assessed the use of context by measuring oral reading fluency and sentence fluency. In both tasks, the resilient readers out-performed the unskilled readers. Interestingly, resilient readers did not differ on these two tasks from good decoders/poor comprehenders. To understand this better, we performed an error analysis using the oral reading fluency task. We classified the types of errors that readers made and then looked across our four groups of readers to see if these errors differed across groups. The most interesting finding from our error analysis was that, when resilient readers made a substitution error (i.e., misread one word for another), their error was semantic in nature, while the other groups’ errors were a mixture of phonological, orthographic, and semantic errors. Thus, resilient readers seem to rely on semantic information.

Our resilient readers were more fluent, as measured by an oral reading fluency task, than our unskilled readers. However, speed is only one aspect of fluency. Reading fluency has been defined as reading with speed, accuracy, and expression (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2000). This last aspect, expression or prosody, has become increasingly important to researchers (e.g., Dowhower, 1991; Klauda & Guthrie, 2008; Miller & Schwanenflugel, 2006, 2008). Prosodic reading is the ability to read in expressive rhythmic and melodic patterns. Prosodic readers segment text into meaningful units marked by appropriate prosodic cues such as pauses, varied duration of those pauses, the raising and lowering of pitch, and lengthening of certain vowel sounds (Dowhower, 1991). Using narrative texts, researchers have generally found that better prosody is typically observed in students with greater reading achievement. Better readers pause less frequently while reading, decrease their pitch at the conclusion of sentences, and do not always heavily stress words as do many poor readers (Klauda & Guthrie, 2008). In addition, variables assessing prosody explain significant variance in reading comprehension beyond reading accuracy and speed (e.g., Miller & Schwanenflugel, 2006). It would be very interesting to see if resilient readers use more prosodic cues while reading compared to both the unskilled readers and the good decoders but poor comprehenders.

Currently, typical assessment measures used by ABE programs come from the list of federally approved tests for providing evidence to the National Reporting System that programs are improving students’ literacy, education, and job-related goals. Although assessment of program outcomes is valuable, it cannot replace assessment of readers’ skills for the purpose of guiding instruction. One clear implication from the current study is the need for reading component assessment in adult basic education (see also Strucker et al., 2007), and this aspect is not covered using the tests on the federally approved list. Those tests typically assess general abilities and do not pinpoint the relative strengths and weaknesses of the adult learners. Our study demonstrates that adults with low literacy skills can have very uneven profiles of reading skills. Other studies have arrived at a similar conclusion (MacArthur, Konold, Glutting,& Alamprese, 2010; Nanda, Greenberg, and Morris, 2010; Sabatini, Sawaki, Shore, & Scarborough, 2010). Consequently, it would be detrimental for programs to assume that poor decoding equates to poor comprehension, or good comprehension goes hand–in-hand with good decoding skills. If component skills assessment is used, instructors would be better equipped to tailor instruction to meet the needs of the individual student, as they would be better acquainted with their strengths and weaknesses. Thus, for the resilient readers and unskilled readers, instructional time would be well spent by reviewing grapheme to phoneme correspondence rules. That is, in order for those readers to progress further, they need to work on their decoding skills. For the good decoders/poor comprehenders, instructional time might be best spent by focusing on the semantic relationships within and among words. An intervention that focuses on how words are composed of parts (i.e., morphemes) and how those parts fit together to alter the meaning of root words might be particularly helpful to help these readers grow and comprehend the reading material better. In addition, an interesting extension of this work would be to conduct a longitudinal study examining growth across these four groups of readers. Given their different reading profiles, they may have very different developmental trajectories as well.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by Grant Number R15HD067755 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute Of Child Health & Human Development.

Footnotes

The sample was drawn from data reported in a previously published study (Binder, Snyder, Ardoin, & Morris, 2011). For additional demographic information, please refer to that paper.

We wish to thank a reviewer for this explanation.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute Of Child Health & Human Development or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Adams MJ, Huggins AWF. The growth of children’s sight vocabulary: A quick test with educational and theoretical implications. Reading Research Quarterly. 1985;20:262–281. [Google Scholar]

- Binder KS, Chace K, Manning MC. Context Effects on the Naming Speed of Target Words in Less Skilled and More Skilled Adult Readers. Journal of Research in Reading. 2007;30:360–378. [Google Scholar]

- Binder KS, Snyder M, Ardoin SP, Morris RK. Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills: An Effective Tool to Assess Adult Literacy Students? Adult Basic Education and Literacy Journal. 2011;5:150–160. [Google Scholar]

- Blalock WJ. Persistent problems and concerns of young adults with learning disabilities. In: Cruickshank WM, Silver AA, editors. Bridges to tomorrow: The best of ACDL. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press; 1981. pp. 35–55. [Google Scholar]

- Dowhower S. Speaking of Prosody: Fluency’s Unattended Bedfellow. Theory Into Practice. 1991;30(3):165–175. [Google Scholar]

- Francis W, Kucera H. Word frequency counts of modern English. Providence RI: Brown University Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Good RH, Kaminski RA, editors. Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills. 6. Eugene, OR: Institute for the Development of Educational Achievement; 2002. Available: http://dibels.uoregon.edu/ [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg D, Ehri LC, Perin D. Are word-reading processes the same or different in adult literacy students and third-fifth graders matched for reading level? Journal of Educational Psychology. 1997;89:262–275. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg D, Ehri LC, Perin D. Do adult literacy students make the same word- reading and spelling errors as children matched for word-reading age? Scientific Studies of Reading. 2002;6:221–243. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson NE, Doellinger HL. Resilient readers? University students who are poor recoders but sometimes good text comprehenders. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2002;94:64–78. [Google Scholar]

- Klauda SL, Guthrie JT. Relationships of three components of reading fluency to reading comprehension. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2008;100:310–321. [Google Scholar]

- MacArthur CA, Konold TR, Glutting JJ, Alamprese JA. Reading component skills of learners in adult basic education. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2010;43:108–121. doi: 10.1177/0022219409359342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J, Schwanenflugel PJ. Prosody of syntactically complex sentences in the oral reading of young children. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2006;98:839–853. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.98.4.839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J, Schwanenflugel PJ. A Longitudinal Study of the Development of Reading Prosody as a Dimension of Oral Reading Fluency in Early Elementary School Children. Reading Research Quarterly. 2008;43:336–354. doi: 10.1598/RRQ.43.4.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanda AO, Greenberg D, Morris R. Modeling child-based theoretical reading constructs with struggling adult readers. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2010;43:138–153. doi: 10.1177/0022219409359344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction: Reports of the subgroups. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2000. Report of the National Reading Panel. [Google Scholar]

- Read C, Ruyter L. Reading and spelling skills in adults of low literacy. Remedial and Special Education. 1985;6:43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatini JP, Sawaki Y, Shore JR, Scarborough HS. Relationships among reading skills of adults with low literacy. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2010;43:138–153. doi: 10.1177/0022219409359343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanovich KE. Mathtew effects in reading: Some consequences of individual differences in the acquisition of literacy. Reading Research Quarterly. 1986;21:360– 406. [Google Scholar]

- Strucker J, Yamamoto K, Kirsh I. The relationship of the componet skills of reading to IALS performance: Tipping points and five classes of adult literacy learners. 2007 (NCSALL Report #29) Retrieved from http://www.ncsall.net/fileadmin/resources/research/report_29_ials.pdf.

- Thompkins AC, Binder KS. A comparison of the factors affecting reading performance of functionally illiterate adults and children matched by reading level. Reading Research Quarterly. 2003;38:236–258. [Google Scholar]

- Welcome SE, Leonard CM, Chiarello C. Alternate reading strategies and variable asummerty of the planum temporal in adult resilient readers. Brain and Language. 2010;113:73–83. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock RW, McGrew KS, Mather N. Woodcock-Johnson III Test of Achievement. Itasca, IL: Riverside Publishing; 2001. [Google Scholar]