Abstract

Background and Purpose

Menthol, a naturally occurring compound in the essential oil of mint leaves, is used for its medicinal, sensory and fragrant properties. Menthol acts via transient receptor potential (TRPM8 and TRPA1) channels and as a positive allosteric modulator of recombinant GABAA receptors. Here, we examined the actions of menthol on GABAA receptor-mediated currents in intact midbrain slices.

Experimental Approach

Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings were made from periaqueductal grey (PAG) neurons in midbrain slices from rats to determine the effects of menthol on GABAA receptor-mediated phasic IPSCs and tonic currents.

Key Results

Menthol (150–750 μM) produced a concentration-dependent prolongation of spontaneous GABAA receptor-mediated IPSCs, but not non-NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs throughout the PAG. Menthol actions were unaffected by TRPM8 and TRPA1 antagonists, tetrodotoxin and the benzodiazepine antagonist, flumazenil. Menthol also enhanced a tonic current, which was sensitive to the GABAA receptor antagonists, picrotoxin (100 μM), bicuculline (30 μM) and Zn2+ (100 μM), but unaffected by gabazine (10 μM) and a GABAC receptor antagonist, 1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridin-4-yl)methylphosphinic acid hydrate (TPMPA; 50 μM). In addition, menthol potentiated currents induced by the extrasynaptic GABAA receptor agonist THIP/gaboxadol (10 μM).

Conclusions and Implications

These results suggest that menthol positively modulates both synaptic and extrasynaptic populations of GABAA receptors in native PAG neurons. The development of agents that potentiate GABAA-mediated tonic currents and phasic IPSCs in a manner similar to menthol could provide a basis for novel GABAA-related pharmacotherapies.

Keywords: periaqueductal grey, GABA, synaptic neurotransmission, IPSC, tonic current

Introduction

Menthol is a naturally occurring monoterpenoid alcohol derived from the essential oil of mint plants. Menthol has been widely used as a food additive, local anaesthetic, topical analgesic, antipruritic, antimicrobial and gastric sedative. Topical application of menthol to the skin produces cooling sensations, which can range in quality from pleasant to painful, via activation of transient receptor potential (TRP) channels, TRPM8 and TRPA1 (channel nomenclature follows Alexander et al., 2013a), located on the peripheral terminals of cold-sensitive nociceptive afferents (Wasner et al., 2004; Hatem et al., 2006; Vriens et al., 2008).

In addition to peripheral actions, a number of studies have demonstrated that menthol has actions within the CNS. In animal behavioural tests, systemic or direct central administration of menthol produces a variety of effects, including ambulation promoting (Umezu et al., 2001), sedative/general anaesthetic (Watt et al., 2008), anticonvulsant (Zhang et al., 2008), analgesic (Proudfoot et al., 2006; Su et al., 2011; Pan et al., 2012) and nootropic (Bhadania et al., 2012) actions. In the sensory system, menthol is thought to act at TRPM8 channels located predominantly on primary afferent neurons, whereas expression levels for this channel are low or absent in spinal cord and brain tissues (Peier et al., 2002). Other potential cellular targets for menthol within the CNS include voltage-gated sodium (Haeseler et al., 2002; Gaudioso et al., 2012; Pan et al., 2012) and calcium channels (Swandulla et al., 1987; Baylie et al., 2010; Pan et al., 2012; Cheang et al., 2013), 5-HT3 receptors (Ashoor et al., 2013a), nicotinic ACh receptors (Hans et al., 2012; Ashoor et al., 2013b), glycine receptors (Hall et al., 2004) and GABAA receptors (Hall et al., 2004; Watt et al., 2008). In the case of GABAA receptors, menthol acts as a potent positive allosteric modulator of recombinant human GABAA receptors, possibly via binding sites shared with the i.v. anaesthetic agent propofol (Hall et al., 2004; Watt et al., 2008). Consistent with this, recent studies have shown that menthol enhances GABAA receptor-mediated currents in spinal cord dorsal horn (Pan et al., 2012) and hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons in vitro (Zhang et al., 2008). In addition, menthol was found to suppress respiratory rhythm generation in a brainstem–spinal cord preparation via a GABAA receptor-dependent mechanism (Tani et al., 2010).

GABAA receptors are pentameric anion channels composed of various combinations of α1–6, β1–3, γ1–3, δ, ε, π, θ and ρ1–3 subunits (Alexander et al., 2013a). As a general rule, GABAA receptors containing α1–3 and γ2 subunits (α1–3βxγ2) are enriched in synapses and mediate phasic synaptic inhibition, whereas extrasynaptic GABAA receptors mediate tonic inhibition and most commonly contain α4–6 subunits together with either a γ2 or δ subunit (α4/6βxδ and α5βxγ2) (Farrant and Nusser, 2005). In the present study, we examined the effects of menthol on phasic and tonic GABAA receptor-mediated currents in the midbrain periaqueductal grey (PAG), a region that plays a pivotal role in organizing an organism's behavioural responses to threat, stress and pain (Keay and Bandler, 2001). We found that menthol prolonged synaptic GABAA receptor-mediated currents in a concentration-dependent manner, and enhanced a GABAA receptor-mediated tonic current in neurons throughout PAG. These effects were likely to be mediated via interactions with distinct populations of synaptic and δ subunit-lacking extrasynaptic GABAA receptors. The findings implicate modulation of GABAergic activity in the CNS as a possible cellular substrate for behavioural changes observed following central administration of menthol.

Methods

Brain slice preparation

All animal care and experimental procedures complied with guidelines set out by the National Health and Medical Research Council ‘Australian code of practice for the care and use of animals for scientific purposes’ and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Ethics Committee. All studies involving animals are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath et al., 2010). A total of 62 animals were used in the experiments described here.

Experiments were carried out on male and female Sprague-Dawley rats (2–4 weeks old) obtained from Animal Resources Centre (Canning Vale, Australia). Animals were deeply anaesthetized with isoflurane and then decapitated. Transverse midbrain slices (300 μm) containing the PAG were cut using a vibratome (VT1200S, Leica Microsystems, Nussloch, Germany) in ice-cold artificial CSF (ACSF), as described previously (Drew et al., 2008). PAG slices were maintained at 34°C in a submerged chamber containing ACSF equilibrated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. The slices were then individually transferred to a chamber and superfused continuously (2.0–2.5 mL·min−1) with ACSF (34°C) of composition (in mM): 126 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.4 NaH2PO4, 1.2 MgCl2, 2.4 CaCl2, 11 glucose and 25 NaHCO3.

Electrophysiology

PAG neurons were visualized using infrared Dodt-tube contrast gradient optics on an upright microscope (BX51; Olympus, Sydney, Australia). Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings (Axopatch 200B; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) of synaptic currents (holding potential, −70 mV) were made from ventrolateral, lateral and dorsolateral PAG neurons using a CsCl-based internal solution containing (in mM): 140 CsCl, 0.2 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 1 MgCl2, 2 MgATP and 0.3 NaGTP (pH 7.3; osmolarity, 280–285 mOsm·L−1). Series resistance (<25 MΩ) was compensated by 80% and continuously monitored during experiments. Liquid junction potentials of −4 mV were corrected. All recordings of spontaneous IPSCs and tonic GABAA receptor-mediated currents were obtained in the presence of the non-NMDA glutamate receptor antagonist 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX) (5 μM) and the glycine receptor antagonist strychnine (3 μM), whereas miniature IPSCs were isolated by further addition of the sodium channel blocker tetrodotoxin (TTX) (0.3 μM). All recordings of spontaneous EPSCs were obtained in the presence of the GABAA receptor antagonist picrotoxin (100 μM) and strychnine (3 μM). IPSCs and EPSCs were inward currents with the internal/externals solutions used in these experiments.

Data analysis

IPSCs and EPSCs were filtered (2, 5 kHz low-pass filter) and sampled (10, 20 kHz) for online and later offline analysis (Axograph X; AxoGraph Scientific, Sydney, Australia). Spontaneous IPSCs and EPSCs above a preset threshold (2.5–4.5 SDs above baseline noise) were automatically detected by a sliding template algorithm, then manually checked offline. Multi-peak PSCs were excluded from analysis of PSC kinetics, whereas all PSCs, including multi-peak events, were included in the analysis of PSC frequency. The IPSC and EPSC decay phases were best fit by two exponentials, and results are presented as weighted decay time, τw = [Afast × τfast + Aslow × τslow]/[Afast + Aslow], where A and τ are the amplitudes and time constants for the fast and slow components of IPSC decay phases. Synaptic charge transfer, Q, was calculated as the area under averaged PSC traces. The membrane holding current (Iholding) and noise/variance (Ivar) were measured in segments of traces where PSCs were absent.

All numerical data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical comparisons of individual drug effects were made using paired Student's t-test and comparisons between treatment groups with an unpaired Student's t-test or one-way anova using Dunnett's correction for post hoc comparisons. Differences were considered significant if P < 0.05.

Materials

Bicuculline, CNQX, HC-030031, picrotoxin, strychnine hydrochloride, (−)-menthol, 4,5,6,7-tetrahydroisoxazolo[5,4-c]pyridin-3-ol hydrochloride (THIP, gaboxadol), ZnCl2 and (1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridin-4-yl)methylphosphinic acid hydrate (TPMPA) were obtained from Sigma (Sydney, Australia); capsazepine and gabazine (SR95531) from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK); flumazenil and TTX from Ascent Scientific (Bristol, UK); and icilin from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Stock solutions of drugs were made in distilled water, except menthol (in ethanol vehicle, ethanol:ACSF ≤ 1:2000), flumazenil, capsazepine, HC-030031 and icilin (in dimethyl sulfoxide vehicle, dimethyl sulfoxide:ACSF ≤ 1:3000), then diluted to working concentrations in ACSF immediately before use and applied by superfusion.

Results

Menthol prolongs the duration of spontaneous IPSCs, but not EPSCs

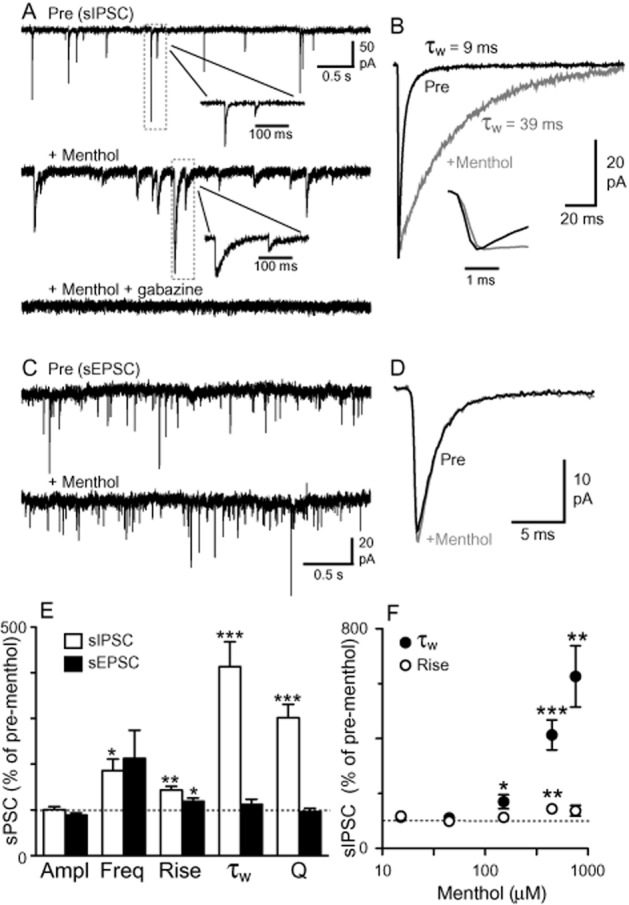

Superfusion of menthol (450 μM) prolonged the duration of spontaneous IPSCs in all PAG neurons tested ( Figures 1A,B and 5A; n = 17). Specifically, menthol produced an increase in the IPSC 10–90% rise time, weighted decay time (τw) and synaptic charge transfer (Q) (Figure 1E; P < 0.001–0.05; Table 2013a). The increase in τw produced by menthol resulted from a similar increase in both τfast (323 ± 52% of baseline) and τslow (276 ± 89% of baseline). Menthol had no significant effect on IPSC amplitude (P = 0.9) and produced a variable but significant increase in IPSC frequency (P = 0.04) (Figure 1E; Table 2013a). The effect of menthol on these spontaneous IPSC parameters was similar in the ventrolateral/lateral (n = 7) and dorsolateral subregions (n = 10) of the PAG (P > 0.05). IPSCs recorded in the presence of menthol were abolished by the competitive GABAA receptor antagonist gabazine (10 μM, n = 3; Figure 1A), confirming that they were mediated by GABAA receptors. Furthermore, superfusion of ethanol vehicle (dilution 1:2000 absolute ethanol in ACSF) had no effect on spontaneous IPSCs or Iholding (P > 0.05, n = 4, data not shown).

Figure 1.

Menthol prolongs the duration of spontaneous GABAA IPSCs, but not non-NMDA EPSCs in PAG neurons. (A) Representative traces of spontaneous IPSCs before and during superfusion of menthol (450 μM) and following addition of gabazine (10 μM). (B) Averaged traces of IPSCs from the same neuron as shown in (A), recorded before (pre) and during menthol. Inset: expanded normalized IPSCs, demonstrating a slowing of the rise time during menthol. (C) Representative traces of spontaneous EPSCs before and during superfusion of menthol (450 μM). (D) Averaged traces of EPSCs from the same neuron as shown in (B), recorded before (pre) and during menthol. (E) Summary bar chart showing the effects of menthol (450 μM) on spontaneous IPSC and EPSC amplitude (Ampl), frequency (Freq), 10–90% rise time (Rise), weighted decay time (τw) and synaptic charge transfer (Q). (F) Concentration–response relationship for the effect of menthol on spontaneous IPSC-weighted decay time and rise time (at concentrations 15, 45, 150, 450 and 750 μM, n = 3, 5, 6, 17, 4). Each point represents the mean ± SEM of 3–17 neurons. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 versus baseline pre-menthol level.

Figure 5.

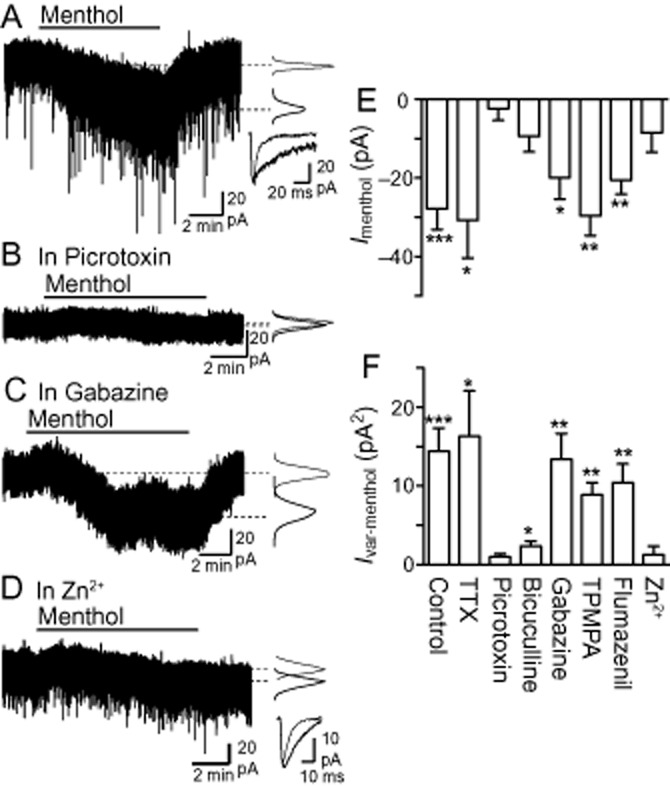

Menthol enhances the tonic GABAA receptor-mediated current. Representative current traces from different PAG neurons during superfusion of menthol (450 μM) in (A) control untreated slices, and slices pre-incubated in (B) picrotoxin (100 μM), (C) gabazine (10 μM) and (D) Zn2+ (100 μM). Insets in (A–D) are probability density distributions of holding current, and in (A, D) averaged spontaneous IPSCs before and during menthol (thin and thick lines respectively). (E, F) Summary bar charts showing changes in (E) holding current (Imenthol) and (F) holding current variance (Ivar-menthol), produced by menthol in untreated slices (control) and slices pre-incubated in TTX (0.3 μM), picrotoxin (100 μM), bicuculline (30 μM), gabazine (10 μM), TPMPA (50 μM), flumazenil (10 μM) and Zn2+ (100 μM). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 when comparing values before and during addition of menthol.

Table 1.

Effect of menthol on spontaneous IPSCs and EPSCs

| Ampl (pA) | Freq (s−1) | Rise time (ms) | Decay time (ms) | Charge transfer (fC) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sIPSC | |||||

| Pre | 42 (5) | 2.7 (1.0) | 0.58 (0.04) | 6.9 (0.6) | 336 (25) |

| +Menthol | 38 (3) | 5.0 (2.0)* | 0.83 (0.06)*** | 28.0 (3.9)*** | 960 (85)*** |

| mIPSC | |||||

| Pre | 42 (3) | 1.5 (0.4) | 0.59 (0.01) | 7.4 (0.4) | 318 (17) |

| +Menthol | 51 (5) | 2.1 (0.5) | 0.79 (0.05)* | 29.8 (5.8)* | 1264 (151)** |

| sEPSC | |||||

| Pre | 22 (2) | 3.9 (1.3) | 0.52 (0.10) | 2.0 (0.2) | 60 (4) |

| +Menthol | 19 (2) | 5.6 (1.9) | 0.59 (0.08)* | 2.2 (0.2) | 56 (3) |

Data shown as mean (SEM) before and during application of menthol (450 μM) for spontaneous IPSCs (sIPSCs), miniature IPSCs (mIPSCs) and spontaneous EPSCs (sEPSCs).

P < 0.05,

0.01,

0.001 for Pre versus +Menthol (sIPSC, n = 17; mIPSC, n = 5; sEPSC, n = 7).

The slowing of spontaneous IPSC decay times by menthol was concentration dependent, with significant increases detected at concentrations ≥150 μM (Figure 1F; n = 3–17). In contrast, IPSC rise times did not appear to be affected by menthol in a concentration-dependent manner, with a significant increase being observed only at 450 μM (Figure 1F). Furthermore, there was no correlation between the effect of menthol (450 μM) on IPSC rise and decay times in individual neurons (Pearson's correlation coefficient, r2 = 0.02, P > 0.05, n = 17), suggesting that the change in rise times may have been a non-specific effect of menthol. At higher concentrations (≥750 μM), menthol dramatically increased baseline noise, which obscured many IPSCs and precluded the determination of the EC50 of menthol's effect on IPSC decay time. The menthol (450 μM)-induced changes in IPSC rise and decay times and charge transfer persisted in the presence of TTX (0.3 μM, Table 2013a, n = 5), indicating that these effects of menthol were action potential independent and likely to be mediated by a direct effect at the GABAergic synapse.

In contrast to IPSCs, superfusion of menthol (450 μM) had no significant effect on spontaneous EPSC frequency, amplitude, decay time or charge transfer (Table 2013a, Figure 1C–E; P > 0.05, n = 7). As observed for IPSCs, however, menthol produced a significant increase in the rise time of spontaneous EPSCs (Figure 1E; P = 0.04). The spontaneous EPSCs were abolished by addition of CNQX (5 μM, n = 6, data not shown).

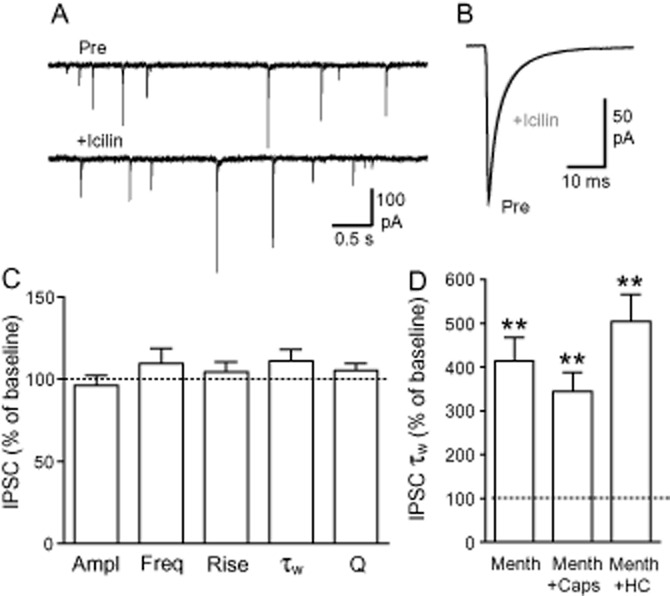

Menthol actions occur independently of TRP channel activation

Menthol interacts with several members of the TRP channel family including, primarily, TRPM8 and TRPA1. To determine whether these channels may have contributed to the actions of menthol, we examined the effects of several TRPM8/A1 agonists and antagonists. Superfusion of the TRPM8 agonist icilin (3 μM) had no significant effect on spontaneous IPSC amplitude, frequency, rise time, decay time or charge transfer (Figure 2A–C; P > 0.05, n = 10). In slices pretreated with the non-selective TRPM8/TRPV1 antagonist capsazepine (20 μM) or the TRPA1 antagonist HC-030031 (50 μM), menthol (450 μM) increased the weighted decay time of IPSCs (Figure 2D; P < 0.01 in each case, n = 5 and 5 respectively). The effect of menthol in the presence of capsazepine and HC-030031 was not significantly different to that observed under control conditions (P > 0.05). These results indicate that TRPM8 and TRPA1 channels do not mediate the effects of menthol on spontaneous IPSCs.

Figure 2.

Menthol effects on IPSCs are not dependent on TRPM8 or TRPA1 channel activation. (A) Representative traces showing spontaneous IPSCs before and during superfusion of icilin (3 μM). (B) Averaged traces of IPSCs from the same neuron as shown in (A), recorded before (control) and during icilin. (C) Summary bar chart of icilin effects on IPSC amplitude (Ampl), frequency (Freq), 10–90% rise time (Rise), weighted decay time (τw) and synaptic charge transfer (Q). (D) Bar chart showing the effects of menthol (450 μM) on IPSC-weighted decay times in the absence and presence of capsazepine (Caps, 20 μM) and HC-030031 (HC, 50 μM). **P < 0.01 versus baseline control.

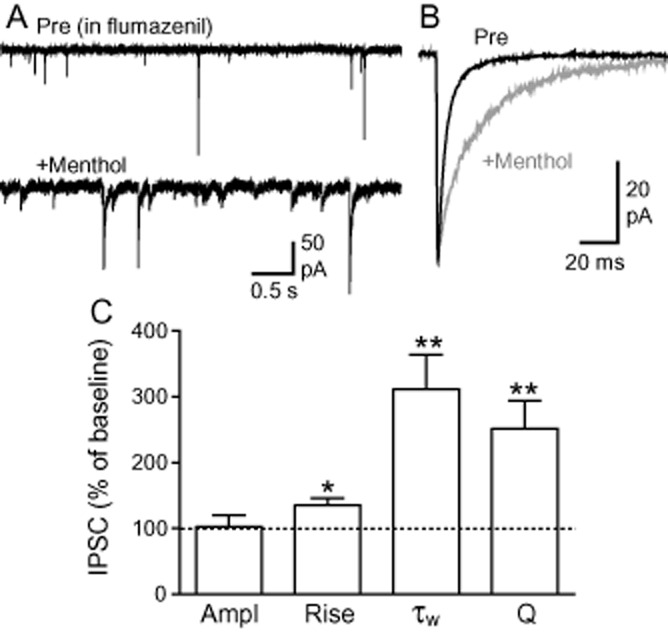

Menthol actions are not mediated via the GABAA receptor benzodiazepine binding site

Previous studies have demonstrated menthol to be a positive allosteric modulator of recombinant GABAA receptors via a binding site distinct to that of benzodiazepines (Hall et al., 2004; Watt et al., 2008). We examined whether this was also the case in native PAG neurons. In slices pretreated with the benzodiazepine antagonist flumazenil (10 μM), menthol produced changes in spontaneous IPSC rise time, decay time and charge transfer that were not significantly different to those observed with menthol alone (P > 0.05, n = 6) (Figure 3). This indicates that menthol modulation of IPSC kinetics in PAG neurons also occurs via a mechanism distinct to that of benzodiazepines.

Figure 3.

Menthol effects on IPSCs are not mediated via the benzodiazepine binding site on GABAA receptors. (A) Representative traces showing spontaneous IPSCs before (pre) and during menthol (450 μM) in the presence of flumazenil (10 μM). (B) Averaged traces of IPSCs from the same neuron as shown in (A), recorded before (pre) and during menthol. (C) Summary bar chart showing the effects of menthol on IPSCs in the presence of flumazenil. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus baseline control.

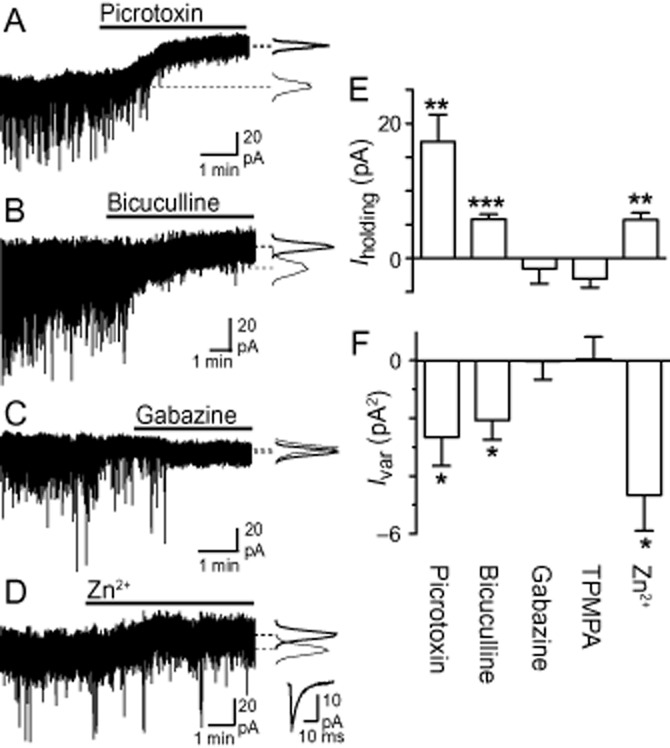

Characterization of GABAA receptor-mediated tonic currents

We next investigated whether tonic GABAA receptor-mediated currents occur within PAG, as previously described in other brain regions, by examining the effect of a range of GABAA/C receptor antagonists (Farrant and Nusser, 2005). Superfusion of the GABAA receptor channel blocker picrotoxin (100 μM, n = 7) abolished spontaneous IPSCs and produced an outward shift in Iholding (Figure 4A and E; P = 0.005). This picrotoxin-induced decrease in Iholding was accompanied by a reduction in Ivar (Figure 4A and F; P = 0.04), consistent with the suppression of a tonic GABAA receptor-mediated conductance. The competitive GABAA receptor antagonist bicuculline (30 μM, n = 6) also abolished spontaneous IPSCs and produced a small but significant outward shift in Iholding and a decrease in Ivar (Figure 4B, E and F; P = 0.004 and 0.03). In contrast, gabazine (10 μM, n = 8) abolished spontaneous IPSCs, but had no effect on either Iholding or Ivar (Figure 4C, E and F; P = 0.5, 0.9). The GABAC receptor antagonist TPMPA (50 μM, n = 6) had no significant effect on spontaneous IPSCs (data not shown), Iholding or Ivar (Figure 4E and F; P = 0.07 and 0.9).

Figure 4.

A tonic GABAA receptor-mediated current is present in PAG neurons. Representative current traces from different PAG neurons during superfusion of (A) picrotoxin (100 μM), (B) bicuculline (30 μM), (C) gabazine (10 μM) and (D) Zn2+ (100 μM). Insets in (A–D) are probability density distributions of holding current, and in (D) averaged spontaneous IPSCs before and during Zn2+ (thin and thick lines respectively). (E, F) Summary bar charts showing the effects of picrotoxin (100 μM), bicuculline (30 μM), gabazine (10 μM), TPMPA (50 μM) and Zn2+ (100 μM) on (E) holding current (Iholding) and (F) holding current variance (Ivar). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 when comparing values before and during addition of each agent.

This pharmacological profile is consistent with menthol acting at extrasynaptic GABAA receptors. To further investigate this possibility, we examined the effect of Zn2+ on basal tonic currents in the PAG. In the micromolar range, Zn2+ has little effect on synaptic γ2 subunit-containing GABAA receptors, but greatly reduces currents mediated by GABAA receptors that lack γ2 subunits, including αβ and δ-GABAA receptors (Saxena and Macdonald, 1994; 1996,; Krishek et al., 1998). Superfusion of Zn2+ (100 μM, n = 5) produced an outward shift in Iholding and a decrease in Ivar (Figure 4D, E and F; P = 0.005 and 0.02), similar to that observed with bicuculline. In these cells, Zn2+ also produced a small but significant decrease in the amplitude of spontaneous IPSCs (P = 0.001, amplitude = 34 ± 7 and 31 ± 6 pA before and during Zn2+, respectively), but had no effect on their kinetics (Figure 4D; rise time = 0.71 ± 0.07 and 0.72 ± 0.12, P = 0.9, τw = 5.5 ± 0.4 and 5.2 ± 0.5 ms, P = 0.5, before and during Zn2+ respectively). These results confirm the presence of an extrasynaptic GABAA receptor-mediated tonic current in our PAG slice preparation.

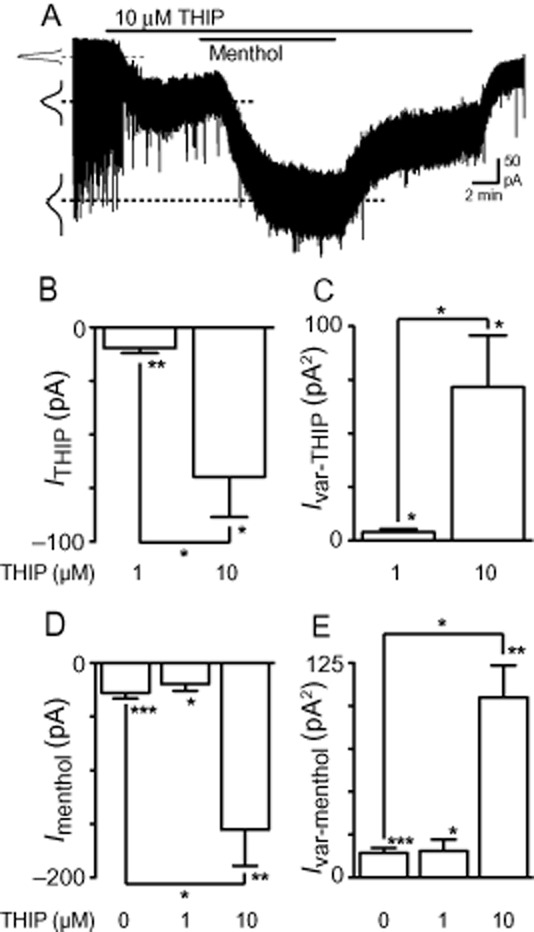

Menthol enhances tonic currents

Next, we examined whether modulation of GABAA receptors by menthol could enhance this basal tonic current. Superfusion of menthol (450 μM) for 8–10 min caused a slowly developing and reversible inward shift in Iholding (P < 0.001) in 14 out of 16 PAG neurons tested (Figure 5A and E). This inward shift in Iholding was accompanied by a marked increase in Ivar (P < 0.001) (Figure 5A and F). There was no correlation between the magnitude of the change in Iholding during menthol application and the change in IPSC decay time for each cell (Pearson's correlation coefficient, r2 = −0.16, P > 0.05, n = 13). The menthol-induced increase in Iholding and Ivar persisted in the additional presence of TTX (0.3 μM, P = 0.03 and 0.04, respectively, n = 5) (Figure 5E and F). Menthol also produced an inward shift in Iholding of 37 ± 6 pA (P < 0.01) and 26 ± 5 pA (P < 0.05) in the presence of capsazepine (20 μM, n = 5) and HC-030031 (50 μM, n = 4), respectively, suggesting that TRP channels had no role in the menthol-induced tonic current.

To further investigate the potential molecular targets of menthol, we examined the effect of a range of GABAA/C receptor ligands on the menthol-induced tonic current. In the presence of picrotoxin (100 μM, n = 6), menthol did not produce a significant change in either Iholding (P = 0.5) or Ivar (P = 0.06) (Figure 5B, E and F). In the presence of bicuculline (30 μM, n = 6), menthol did not significantly alter Iholding (P = 0.06), but produced a small increase in Ivar (P = 0.02) (Figure 5E and F). In contrast, gabazine (10 μM, n = 5), TPMPA (50 μM, n = 5) and flumazenil (10 μM, n = 6) had no effect on menthol-induced increases in either Iholding (P < 0.05) or Ivar (P < 0.05) (Figure 5C, E and F). Finally, menthol did not significantly alter Iholding (P = 0.1) or Ivar (P = 0.3) in the presence of Zn2+ (100 μM, n = 6) (Figure 5D, E and F). Additionally, although menthol increased the decay time of spontaneous IPSCs in the presence of Zn2+ (Figure 5D; P = 0.01, n = 6, τw = 5.2 ± 0.5 and 10.6 ± 1.4 ms before and during Zn2+, respectively), this effect was significantly less than observed under control conditions (P = 0.03, τw = 201 ± 26% and 414 ± 54% of the pre-menthol value in the presence and absence of Zn2+ respectively).

Collectively, these results suggest that menthol might be acting at Zn2+-sensitive peri/extrasynaptic δ-GABAA receptors to potentiate basal tonic currents. In the PAG, extrasynaptic α4βδ GABAA receptors have been proposed as a likely candidate for generating tonic currents, as α4 and δ subunits are present on neurons throughout this brain region (Lovick et al., 2005) and are known to contribute to tonic currents elsewhere in the CNS (Farrant and Nusser, 2005). To test this possibility, we investigated the effect of menthol in the presence of the GABAA receptor agonist THIP (gaboxadol). Superfusion of THIP (1 μM, n = 6), at a concentration that is selective for δ-GABAA receptors (Herd et al., 2009; Meera et al., 2011), produced small but significant increases in Iholding (P = 0.009) and Ivar (P = 0.04) (Figure 6B and C). At a higher concentration, THIP (10 μM, n = 6) markedly increased both Iholding (P = 0.01) and Ivar (P = 0.03) (Figure 6A–C). These effects were significantly larger than observed using 1 μM THIP (P = 0.01 and 0.02 for Iholding and Ivar respectively). Subsequent addition of menthol (450 μM, n = 6) produced increases in Iholding and Ivar at both 1 and 10 μM THIP concentrations (Figure 6A, D and E; P < 0.0001–.05). However, menthol-induced currents were potentiated above control levels only in the presence of the higher concentration of THIP (P < 0.05 for both Iholding and Ivar) (Figure 6D and E), implying that distinct THIP-sensitive receptor subtypes may be differentially targeted by menthol. It should also be noted that, in several cells (see Figure 6A), the frequency of spontaneous IPSCs appeared to be greatly reduced by 10 μM THIP, which is consistent with the inhibitory actions of THIP on network activity and GABA release described in a previous study (Gao and Smith, 2010). This effect could not be adequately analysed, however, because the increase in noise precluded reliable identification of individual IPSCs.

Figure 6.

THIP produces a tonic current that is enhanced by menthol. (A) Representative current trace from a PAG neuron during superfusion of THIP (10 μM), then addition of menthol (450 μM). Insets are probability density distributions of holding current before and during addition of THIP, then menthol. (B, C) Summary bar charts showing changes in (B) holding current (ITHIP) and (C) holding current variance (Ivar-THIP) produced by 1 and 10 μM THIP. (D, E) Summary bar charts showing changes in (D) holding current (Imenthol) and (E) holding current variance (Ivar-menthol) produced by menthol (450 μM) in the absence (0 μM) and presence of 1 and 10 μM THIP. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 when comparing values before and during addition of each agent and comparing between treatment groups.

Discussion

The present study has demonstrated that menthol potentiates both phasic and tonic GABAA receptor-mediated currents in neurons located within all subregions of the PAG in vitro. The effect of menthol on the tonic current appears to be mediated by extrasynaptic GABAA receptors that lack that a δ subunit. This menthol-induced enhancement of GABAergic inhibition within the PAG has the potential to modulate the analgesic and anxiolytic functions of this brain region.

Menthol prolonged the decay time of spontaneous IPSCs in PAG neurons, resulting in an approximately threefold increase in synaptic charge transfer at the concentration used in this study. This differs to a previous study in which menthol enhanced a tonic current but had no effect on IPSC kinetics in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons (Zhang et al., 2008). The effect of menthol on IPSC decay time was concentration dependent, with significant changes observed at concentrations of 150 μM and above, which is in accord with concentration–response profiles previously reported for menthol modulation of GABAA receptor activity (Hall et al., 2004; Watt et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2008; Pan et al., 2012). The increase in IPSC decay time produced by menthol was not accompanied by changes in IPSC amplitude, consistent with its proposed role as an allosteric modulator of GABAA receptors (Hall et al., 2004; Watt et al., 2008). Menthol effects were unaltered by TRPM8 and TRPV1/TRPA1 channel antagonists and not mimicked by the selective TRPM8 agonist icilin, ruling out possible TRP channel involvement. The menthol enhancement of IPSC decay times and tonic current were also unaffected by flumazenil, indicating that menthol was not acting via the benzodiazepine binding site on GABAA receptors. This is in agreement with a previous study in which modulation of recombinant α1β2γ2 (‘synaptic-type’) GABAA receptor activity by menthol, but not benzodiazepines, was abolished by point mutations in the β2 subunit (Watt et al., 2008). Collectively, these results suggest that menthol acts as positive modulator of synaptic GABAA receptors in PAG neurons, possibly via interaction with β2 subunits.

Despite having little effect on IPSCs per se, we found that Zn2+ greatly reduced the effect of menthol on IPSC decay time. Although there is currently little information available regarding the subcellular localization of GABAA receptor subtypes in the PAG, at other synapses α4, α6 and/or δ subunit-containing GABAA receptors are concentrated at perisynaptic sites, where they are thought to contribute to IPSC decay kinetics during GABA spillover following synaptic release (Rossi and Hamann, 1998; Wei et al., 2003; Bright et al., 2011; Herd et al., 2013). Indeed, the δ-GABAA receptor modulator AA29504 was recently shown to prolong miniature IPSC decay time in mouse dentate gyrus granule cells, an effect that was abolished by Zn2+ (Vardya et al., 2012). The authors proposed that AA29504 might selectively increase the GABA affinity of perisynaptic δ-GABAA receptors, thereby promoting their activation during synaptic transmission. It is possible that menthol produces a similar effect on Zn2+-sensitive perisynaptic GABAA receptors in the PAG. Alternatively, Zn2+, an allosteric modulator of GABAA receptor gating (Barberis et al., 2000), could potentially interfere with menthol binding and/or actions at synaptic GABAA receptors. Further research will be required to address these possibilities. In addition to IPSC kinetics, menthol produced a variable increase in the frequency of spontaneous IPSCs. Interestingly, in tractus solitarius neurons, propofol increases spontaneous IPSC frequency by potentiating GABAA receptor-mediated depolarization of presynaptic GABAergic terminals (Jin et al., 2009). It is not known, however, if such a mechanism also occurs in PAG. Regardless of underlying mechanisms, these results indicate that menthol is likely to produce complex neuronal network effects within the PAG.

In the present study, we observed a tonic GABAergic current under basal conditions in PAG slices, which was enhanced by menthol. The tonic current was likely to be mediated by GABAA receptors because it was observed in the presence of strychnine and CNQX, was sensitive to picrotoxin and bicuculline, but was unaffected by the GABAC receptor antagonist TPMPA. The observed enhancement of tonic current by menthol is similar to that reported in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons, where menthol increased a bicuculline-sensitive tonic current (Zhang et al., 2008). Several lines of evidence indicate that distinct populations of GABAA receptors were responsible for the tonic current and phasic IPSCs reported here. First, there was no correlation between the effect of menthol on tonic current and IPSC decay time in individual neurons, implying that the two phenomena occurred independently. Second, these currents could be differentiated pharmacologically based on their sensitivity to various GABAA receptor antagonists. Thus, gabazine abolished phasic IPSCs but had no effect on the tonic basal and menthol-induced currents. This pharmacological profile is similar to tonic GABAA receptor-mediated currents observed in the hippocampus (Bai et al., 2001; Yeung et al., 2003; McCartney et al., 2007). Conversely, Zn2+ greatly reduced tonic basal and menthol-induced currents, while producing only a modest (∼10%) reduction in the amplitude of IPSCs. This is consistent with the lower Zn2+ sensitivity of γ2 subunit-containing synaptic GABAA receptors (Draguhn et al., 1990; Hosie et al., 2003).

Although application of 1 μM THIP produced only a small (∼10 pA) tonic current in PAG neurons and had no effect on menthol-induced tonic currents, it produced a substantial inward current and marked potentiation of menthol-induced tonic currents at a concentration of 10 μM. Together, these observations suggest that δ-GABAA receptors are likely to contribute only partly to the tonic current observed in PAG slices under our experimental conditions, and that these receptors are unlikely to be a target for menthol because δ-subunits confer sub-micromolar sensitivity to THIP (Herd et al., 2009; Meera et al., 2011). These observations also argue against involvement of γ2 subunit-containing GABAA receptors because αβγ2 receptor combinations display relatively weak sensitivity to THIP, with EC50s typically above 100 μM (Ebert et al., 1994; Meera et al., 2011). Thus, menthol is likely to be acting on a population of a THIP- and Zn2+-sensitive, γ2/δ subunit-lacking extrasynaptic GABAA receptors in PAG neurons. In native cerebellar neurons, THIP produces a tonic current in δ-subunit knockout mice with a similar mid-range concentration dependence (EC50 ∼20 μM) as γ2/δ-lacking α4/6β3 GABAA receptors (Meera et al., 2011). Indeed, it has been suggested that αβ GABAA receptor combinations are abundant in brain tissue (Bencsits et al., 1999), are sensitive to Zn2+ (Draguhn et al., 1990; Smart et al., 1991) and have been implicated in the generation of tonic currents in hippocampal pyramidal neurons (Mortensen and Smart, 2006).

Tonic GABAA receptor-mediated currents are generally thought to require the continued presence of low levels of extracellular GABA (Semyanov et al., 2004). One such source of extrasynaptic GABA could arise from action potential-dependent spillover of GABA following synaptic release (Hamann et al., 2002; Bright et al., 2007; Gao and Smith, 2010). The menthol-induced tonic current was unaffected by TTX, however, suggesting that GABA spillover did not contribute significantly to this current under our experimental conditions. Alternatively, tonic currents could arise from the constitutive activity of extrasynaptic GABAA receptors in the absence of ambient GABA (Birnir et al., 2000; McCartney et al., 2007; Wlodarczyk et al., 2013). Indeed, in the present study, the insensitivity of the basal tonic current to gabazine and the small effect produced by bicuculline (relative to that of picrotoxin) is very similar to the pharmacological profile reported in the earlier studies. Thus, the results could be explained by the neutral and inverse agonist properties of these two competitive ligands, respectively, when binding to constitutively active GABAA receptors in the absence of GABA (Ueno et al., 1997; McCartney et al., 2007; Wlodarczyk et al., 2013). In contrast, picrotoxin, an open channel blocker, would be expected to inhibit GABAA receptor activity regardless of whether it was mediated by GABA-dependent or independent gating. Additional research will be required to elucidate the source of tonic GABAA receptor-mediated currents in the PAG slice preparation.

There is accumulating evidence that centrally administered menthol produces a variety of behavioural effects in animal models and that some of these are mediated by GABAA receptor-mediated mechanisms (Watt et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2008; Tani et al., 2010). Interestingly, GABAA receptors are a major target for many sedatives and general anaesthetics (Millan, 2003; Hemmings et al., 2005). In particular, potentiation of tonic GABAA receptor-mediated inhibition has been proposed to play an important role in the suppression of neuronal excitability by general anaesthetics (Bieda and MacIver, 2004). The development of agents that target GABAA-mediated tonic currents and phasic IPSCs in a manner similar to menthol could provide a basis for novel GABAA-related pharmacotherapies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council Project Grants (1003097 to C. W. V. and G. M. D., 457068 and 1028183 to A. K. G.) and Macquarie University SIS to A. K. G.

Glossary

- CNQX

6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione

- THIP

4,5,6,7-tetrahydroisoxazolo[5,4-c]pyridin-3-ol hydrochloride

gaboxadol

- TPMPA

1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridin-4-yl)methylphosphinic acid hydrate

- TTX

tetrodotoxin

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Catterall WA, et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: Ion Channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2013a;170:1607–1651. doi: 10.1111/bph.12447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Catterall WA, et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: Ligand-Gated Ion Channels. Br J Pharmacol. 170:1582–1606. doi: 10.1111/bph.12446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashoor A, Nordman J, Veltri D, Susan Yang KH, Shuba Y, Al Kury L, et al. Menthol inhibits 5-HT3 receptor-mediated currents. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013b doi: 10.1124/jpet.113.203976. 2013a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashoor A, Nordman JC, Veltri D, Yang KH, Al Kury L, Shuba Y, et al. Menthol binding and inhibition of α7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. PLoS ONE. 2013b;8:e67674. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai D, Zhu G, Pennefather P, Jackson MF, MacDonald JF, Orser BA. Distinct functional and pharmacological properties of tonic and quantal inhibitory postsynaptic currents mediated by γ-aminobutyric acid(A) receptors in hippocampal neurons. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59:814–824. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.4.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barberis A, Cherubini E, Mozrzymas JW. Zinc inhibits miniature GABAergic currents by allosteric modulation of GABAA receptor gating. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8618–8627. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-23-08618.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylie RL, Cheng H, Langton PD, James AF. Inhibition of the cardiac L-type calcium channel current by the TRPM8 agonist, (-)-menthol. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2010;61:543–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bencsits E, Ebert V, Tretter V, Sieghart W. A significant part of native γ-aminobutyric acidA receptors containing α4 subunits do not contain γ or δ subunits. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19613–19616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.28.19613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhadania M, Joshi H, Patel P, Kulkarni VH. Protective effect of menthol on beta-amyloid peptide induced cognitive deficits in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;681:50–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieda MC, MacIver MB. Major role for tonic GABAA conductances in anesthetic suppression of intrinsic neuronal excitability. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:1658–1667. doi: 10.1152/jn.00223.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnir B, Everitt AB, Lim MS, Gage PW. Spontaneously opening GABA(A) channels in CA1 pyramidal neurones of rat hippocampus. J Membr Biol. 2000;174:21–29. doi: 10.1007/s002320001028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bright DP, Aller MI, Brickley SG. Synaptic release generates a tonic GABA(A) receptor-mediated conductance that modulates burst precision in thalamic relay neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2560–2569. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5100-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bright DP, Renzi M, Bartram J, McGee TP, MacKenzie G, Hosie AM, et al. Profound desensitization by ambient GABA limits activation of δ-containing GABAA receptors during spillover. J Neurosci. 2011;31:753–763. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2996-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheang WS, Lam MY, Wong WT, Tian XY, Lau CW, Zhu Z, et al. Menthol relaxes rat aortae, mesenteric and coronary arteries by inhibiting calcium influx. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013;702:79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draguhn A, Verdorn TA, Ewert M, Seeburg PH, Sakmann B. Functional and molecular distinction between recombinant rat GABAA receptor subtypes by Zn2+ Neuron. 1990;5:781–788. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90337-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew GM, Mitchell VA, Vaughan CW. Glutamate spillover modulates GABAergic synaptic transmission in the rat midbrain periaqueductal grey via metabotropic glutamate receptors and endocannabinoid signaling. J Neurosci. 2008;28:808–815. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4876-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert B, Wafford KA, Whiting PJ, Krogsgaard-Larsen P, Kemp JA. Molecular pharmacology of γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor agonists and partial agonists in oocytes injected with different α, β and γ receptor subunit combinations. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;46:957–963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrant M, Nusser Z. Variations on an inhibitory theme: phasic and tonic activation of GABA(A) receptors. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:215–229. doi: 10.1038/nrn1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H, Smith BN. Tonic GABAA receptor-mediated inhibition in the rat dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus. J Neurophysiol. 2010;103:904–914. doi: 10.1152/jn.00511.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudioso C, Hao J, Martin-Eauclaire MF, Gabriac M, Delmas P. Menthol pain relief through cumulative inactivation of voltage-gated sodium channels. Pain. 2012;153:473–484. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeseler G, Maue D, Grosskreutz J, Bufler J, Nentwig B, Piepenbrock S, et al. Voltage-dependent block of neuronal and skeletal muscle sodium channels by thymol and menthol. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2002;19:571–579. doi: 10.1017/s0265021502000923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall AC, Turcotte CM, Betts BA, Yeung WY, Agyeman AS, Burk LA. Modulation of human GABAA and glycine receptor currents by menthol and related monoterpenoids. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;506:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann M, Rossi DJ, Attwell D. Tonic and spillover inhibition of granule cells control information flow through cerebellar cortex. Neuron. 2002;33:625–633. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00593-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hans M, Wilhelm M, Swandulla D. Menthol suppresses nicotinic acetylcholine receptor functioning in sensory neurons via allosteric modulation. Chem Senses. 2012;37:463–469. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjr128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatem S, Attal N, Willer JC, Bouhassira D. Psychophysical study of the effects of topical application of menthol in healthy volunteers. Pain. 2006;122:190–196. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmings HC, Jr, Akabas MH, Goldstein PA, Trudell JR, Orser BA, Harrison NL. Emerging molecular mechanisms of general anesthetic action. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:503–510. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herd MB, Foister N, Chandra D, Peden DR, Homanics GE, Brown VJ, et al. Inhibition of thalamic excitability by 4,5,6,7-tetrahydroisoxazolo[4,5-c]pyridine-3-ol: a selective role for δ-GABA(A) receptors. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;29:1177–1187. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06680.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herd MB, Brown AR, Lambert JJ, Belelli D. Extrasynaptic GABAA receptors couple presynaptic activity to postsynaptic inhibition in the somatosensory thalamus. J Neurosci. 2013;33:14850–14868. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1174-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosie AM, Dunne EL, Harvey RJ, Smart TG. Zinc-mediated inhibition of GABA(A) receptors: discrete binding sites underlie subtype specificity. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:362–369. doi: 10.1038/nn1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin YH, Zhang Z, Mendelowitz D, Andresen MC. Presynaptic actions of propofol enhance inhibitory synaptic transmission in isolated solitary tract nucleus neurons. Brain Res. 2009;1286:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.06.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keay KA, Bandler R. Parallel circuits mediating distinct emotional coping reactions to different types of stress. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2001;25:669–678. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(01)00049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. NC3Rs Reporting Guidelines Working Group. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1577–1579. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishek BJ, Moss SJ, Smart TG. Interaction of H+ and Zn2+ on recombinant and native rat neuronal GABAA receptors. J Physiol. 1998;507(Pt 3):639–652. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.639bs.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovick TA, Griffiths JL, Dunn SM, Martin IL. Changes in GABA(A) receptor subunit expression in the midbrain during the oestrous cycle in Wistar rats. Neuroscience. 2005;131:397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCartney MR, Deeb TZ, Henderson TN, Hales TG. Tonically active GABAA receptors in hippocampal pyramidal neurons exhibit constitutive GABA-independent gating. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:539–548. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.028597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath J, Drummond G, Kilkenny C, Wainwright C. Guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1573–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00873.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meera P, Wallner M, Otis TS. Molecular basis for the high THIP/gaboxadol sensitivity of extrasynaptic GABA(A) receptors. J Neurophysiol. 2011;106:2057–2064. doi: 10.1152/jn.00450.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan MJ. The neurobiology and control of anxious states. Prog Neurobiol. 2003;70:83–244. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(03)00087-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen M, Smart TG. Extrasynaptic αβ subunit GABAA receptors on rat hippocampal pyramidal neurons. J Physiol. 2006;577(Pt 3):841–856. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.117952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan R, Tian Y, Gao R, Li H, Zhao X, Barrett JE, et al. Central mechanisms of menthol-induced analgesia. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;343:661–672. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.196717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peier AM, Moqrich A, Hergarden AC, Reeve AJ, Andersson DA, Story GM, et al. A TRP channel that senses cold stimuli and menthol. Cell. 2002;108:705–715. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00652-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proudfoot CJ, Garry EM, Cottrell DF, Rosie R, Anderson H, Robertson DC, et al. Analgesia mediated by the TRPM8 cold receptor in chronic neuropathic pain. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1591–1605. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.07.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi DJ, Hamann M. Spillover-mediated transmission at inhibitory synapses promoted by high affinity α6 subunit GABA(A) receptors and glomerular geometry. Neuron. 1998;20:783–795. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena NC, Macdonald RL. Assembly of GABAA receptor subunits: role of the δ subunit. J Neurosci. 1994;14(11 Pt 2):7077–7086. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-11-07077.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena NC, Macdonald RL. Properties of putative cerebellar γ-aminobutyric acid A receptor isoforms. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;49:567–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semyanov A, Walker MC, Kullmann DM, Silver RA. Tonically active GABAA receptors: modulating gain and maintaining the tone. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:262–269. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart TG, Moss SJ, Xie X, Huganir RL. GABAA receptors are differentially sensitive to zinc: dependence on subunit composition. Br J Pharmacol. 1991;103:1837–1839. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12337.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su L, Wang C, Yu YH, Ren YY, Xie KL, Wang GL. Role of TRPM8 in dorsal root ganglion in nerve injury-induced chronic pain. BMC Neurosci. 2011;12:120. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-12-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swandulla D, Carbone E, Schafer K, Lux HD. Effect of menthol on two types of Ca currents in cultured sensory neurons of vertebrates. Pflugers Arch. 1987;409:52–59. doi: 10.1007/BF00584749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tani M, Onimaru H, Ikeda K, Kawakami K, Homma I. Menthol inhibits the respiratory rhythm in brainstem preparations of the newborn rats. Neuroreport. 2010;21:1095–1099. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3283405bad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno S, Bracamontes J, Zorumski C, Weiss DS, Steinbach JH. Bicuculline and gabazine are allosteric inhibitors of channel opening of the GABAA receptor. J Neurosci. 1997;17:625–634. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-02-00625.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umezu T, Sakata A, Ito H. Ambulation-promoting effect of peppermint oil and identification of its active constituents. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;69:383–390. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00543-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vardya I, Hoestgaard-Jensen K, Nieto-Gonzalez JL, Dosa Z, Boddum K, Holm MM, et al. Positive modulation of δ-subunit containing GABA(A) receptors in mouse neurons. Neuropharmacology. 2012;63:469–479. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vriens J, Nilius B, Vennekens R. Herbal compounds and toxins modulating TRP channels. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2008;6:79–96. doi: 10.2174/157015908783769644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasner G, Schattschneider J, Binder A, Baron R. Topical menthol – a human model for cold pain by activation and sensitization of C nociceptors. Brain. 2004;127(Pt 5):1159–1171. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt EE, Betts BA, Kotey FO, Humbert DJ, Griffith TN, Kelly EW, et al. Menthol shares general anesthetic activity and sites of action on the GABA(A) receptor with the intravenous agent, propofol. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;590:120–126. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W, Zhang N, Peng Z, Houser CR, Mody I. Perisynaptic localization of δ subunit-containing GABA(A) receptors and their activation by GABA spillover in the mouse dentate gyrus. J Neurosci. 2003;23:10650–10661. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-33-10650.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wlodarczyk AI, Sylantyev S, Herd MB, Kersante F, Lambert JJ, Rusakov DA, et al. GABA-independent GABAA receptor openings maintain tonic currents. J Neurosci. 2013;33:3905–3914. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4193-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung JY, Canning KJ, Zhu G, Pennefather P, MacDonald JF, Orser BA. Tonically activated GABAA receptors in hippocampal neurons are high-affinity, low-conductance sensors for extracellular GABA. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:2–8. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XB, Jiang P, Gong N, Hu XL, Fei D, Xiong ZQ, et al. A-type GABA receptor as a central target of TRPM8 agonist menthol. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3386. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]