Abstract

Aim

This study aims to investigate the clinical and demographic factors influencing gentamicin pharmacokinetics in a large cohort of unselected premature and term newborns and to evaluate optimal regimens in this population.

Methods

All gentamicin concentration data, along with clinical and demographic characteristics, were retrieved from medical charts in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit over 5 years within the frame of a routine therapeutic drug monitoring programme. Data were described using non-linear mixed-effects regression analysis ( nonmem®).

Results

A total of 3039 gentamicin concentrations collected in 994 preterm and 455 term newborns were included in the analysis. A two compartment model best characterized gentamicin disposition. The average parameter estimates, for a median body weight of 2170 g, were clearance (CL) 0.089 l h−1 (CV 28%), central volume of distribution (Vc) 0.908 l (CV 18%), intercompartmental clearance (Q) 0.157 l h−1 and peripheral volume of distribution (Vp) 0.560 l. Body weight, gestational age and post-natal age positively influenced CL. Dopamine co-administration had a significant negative effect on CL, whereas the influence of indomethacin and furosemide was not significant. Both body weight and gestational age significantly influenced Vc. Model-based simulations confirmed that, compared with term neonates, preterm infants need higher doses, superior to 4 mg kg−1, at extended intervals to achieve adequate concentrations.

Conclusions

This observational study conducted in a large cohort of newborns confirms the importance of body weight and gestational age for dosage adjustment. The model will serve to set up dosing recommendations and elaborate a Bayesian tool for dosage individualization based on concentration monitoring.

Keywords: aminoglycoside, dosing guidelines, neonates, population pharmacokinetics, therapeutic drug monitoring, two compartment model

What is Already Known about this Subject

Gentamicin is one of the most frequently administered drugs to neonates for suspected or proven infections.

Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) has been highly recommended in the past due to variability in drug disposition.

Very preterm newborns need higher doses and longer dosing intervals than term newborns.

What this Study Adds

This study is the largest ever done on an unselected cohort of neonates and confirms the major influence of body weight, gestational and post-natal ages on gentamicin pharmacokinetics.

Our model confirms that recent guidelines for gentamicin dosage decisions are appropriate to reach concentration targets considered effective and safe in neonates.

Introduction

The use of aminoglycosides is limited by their potential ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity, consequent to drug accumulation in the inner ear and kidney [1–5]. Despite their toxicity, aminoglycosides are widely used in clinical practice. In recent guidelines, gentamicin remains the first line of treatment for suspected early-onset neonatal sepsis [6,7]. Pharmacodynamic investigations have shown a concentration-dependent activity, mainly related to the ratio of peak plasma concentration over minimum inhibitory concentration (Cmax : MIC), which should exceed 8 to 10 for optimal efficacy [8].

Gentamicin is essentially eliminated by renal excretion through glomerular filtration and binds to only a limited extent to plasma proteins (between 0–15% [9,10], and up to 30% according to some authors [11]). The majority of nephrons are formed in the third trimester of pregnancy and nephrogenesis is complete between 32 to 36 weeks of gestation [12,13]. In the last decade, preterm births (below 37 weeks of gestation) have constituted about 10% of total births worldwide [12] and the survival rates of these extremely preterm infants have particularly increased. Infants born at 25 weeks of gestation now have up to 80% chance of survival [14]. In this subpopulation, the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is quite low at birth, but this is also typical in term newborns. During the first weeks of life, there is a progressive rise in GFR resulting from an acute increase in cardiac output and renal blood flow induced by birth and a decrease in renal vascular resistance [15]. Thus, renal elimination of gentamicin in neonates is largely linked to both gestational age and post-natal (PNA) age. It is worth noting that, as creatinine crosses the placental barrier, blood creatinine concentrations are not a reliable indicator of renal function in the first days of life as they reflects maternal rather than neonate concentrations [13]. Gentamicin is a polar molecule and is distributed predominantly in extracellular fluid, which varies inversely with gestational age [16,17]. The large amount of extracellular body water in neonates and young infants results in lower plasma concentrations compared with adults for a given body weight-adjusted dosage regimen [18].

Therefore, because of age-associated changes in organ function and body composition, gentamicin treatment regimens must be individualized appropriately to reflect maturation (increase in age) and growth (increase in size). Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM), involving a close monitoring of the exposure of drug plasma concentrations so as to prevent toxicity and lack of efficacy, is the standard of care to optimize the dosage of aminoglycosides. A Bayesian forecasting approach for estimation of individual pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters currently represents the gold-standard approach for TDM [19]. It is becoming increasingly advocated for treatment individualization in neonates [20,21].

The purpose of this study was to characterize the population PK parameters of gentamicin in a large cohort of preterm and term neonates and to investigate the influence of clinical, physiological and environmental factors on the disposition of the drug. The second objective was to evaluate the achievement of target concentrations according to dosage regimen recommendations based on simulations. These recommendations will retrospectively be compared with a dosing regimen based on a two point adjustment approach performed routinely in our hospital within the framework of TDM. The results should ultimately serve to build up gentamicin Bayesian-inspired TDM tools for dosage individualization in patients who need monitoring [22].

Method

Study population

All neonates admitted in the Service of Neonatology of the Lausanne University Hospital between December 2006 and October 2011 and receiving gentamicin were eligible for the study. This retrospective study was approved by the local ethics committee of the Lausanne University Hospital. Initially, 3168 gentamicin concentration measurements collected from 1500 subjects, were retrieved using the clinical information system (MetaVision, iMDsoft, Massachussetts, USA) and the routine TDM database. Of these, 129 samples were excluded from analysis for the following reasons: missing information on drug administration or sampling times, inconsistencies in dosing interval or administered dose or unclear dosing schedules. The following characteristics were systematically collected: gender, body weight (BW) at the time of blood sampling, gestational age (GA), PNA, concomitant treatment with furosemide, dopamine and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (ibuprofen and indomethacin), presence of a patent ductus arterious (PDA) and concomitant respiratory support with invasive or non-invasive ventilation.

Drug administration and serum concentrations

Gentamicin (Garamycin®, Hexal, Holzkirchen, Germany) was administered intravenously over a 30 min infusion, most of the time in association with amoxicillin. The conventional initial dose was 3 mg kg−1 from December 2006 until April 2011, followed by 4 mg kg−1 from May 2011 to October 2011 according to a change in local guidelines. Within the framework of a routine TDM programme in our hospital, plasma drug concentrations were drawn twice, 1 h and 12 h after the first gentamicin dose, in order to individualize the dosage regimen based on a classical two point approach linear regression [23]. Further concentration measurements could be requested by the physician if the treatment was prolonged.

Analytical assay

Serum concentrations were determined by fluorescent polarization immunoassay (Cobas Integra 400 Plus, Roche Diagnostics, Rotkreuz, Switzerland). Lower limits of detection and quantification were, respectively, 0.04 and 0.5 mg l−1. Coefficients of variation (CV) for imprecision were ≤2.5% at 0.9 and 7.8 mg l−1 within run and ≤3.1% at 1.5, 4.4 and 7.0 mg l−1 between runs.

Model-based pharmacokinetic analysis

Base model

The population PK analysis was performed using a non-linear mixed-effect modelling approach with nonmem® (version 7.1.0, ICON Development Solutions, Ellicott City, MD, USA), using first order conditional estimation with interaction (FOCEI). A stepwise procedure was used to identify the model that best fitted the data comparing one and two compartment open models. Exponential errors were used for the description of the between subject variability (BSV) of PK parameters. Proportional, additive and mixed error models were compared which describe the residual variability.

Covariate model

At first, the graphical exploration of continuous covariates (BW, GA, PNA, postmenstrual age (PMA) defined as the sum of PNA and GA) and categorical covariates (gender, co-treatment with furosemide, dopamine and indomethacin, PDA, invasive and non-invasive ventilation) effects were carried out to visualize the relationship between the PK parameters and the covariates. Potentially influencing covariates were then included in the model following a sequential forward selection and backward elimination. Ibuprofen and vancomycin, which can affect renal function, were not administered in this population and their influence could thus not be investigated.

The influence of body weight on gentamicin PK parameters was used as a first covariate characterized using allometric scaling [24].

| (1) |

Other continuous covariates were implemented in the model using a linear (2), allometric (3) or exponential equation (4). Continuous variables were centred on the median:

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

Categorical covariates were implemented in the model according to the following equation:

| (5) |

Since PMA represents the sum of GA and PNA, PNA or GA were not considered if PMA was already included in the model and vice versa.

Parameter estimation and model selection

Difference in objective function value (ΔOF), nonmem® goodness-of-fit statistics, along with diagnostic goodness-of-fit plots, were used for model comparison. Since ΔOF between any two hierarchical models approximates a χ2 distribution, it was considered statistically significant if it exceeded 3.8 (P < 0.05) and 6.6 (P < 0.01) points respectively, for one additional parameter during model building and backward deletion procedures. Akaike's information criterion (AIC) was used for non-hierarchical models. Shrinkage was also examined. When more than one covariate describing the same effect (GA, PNA and PMA) was found significant, the covariate causing the largest drop in objective function was preferred. A sensitivity analysis was performed for patients with absolute values for conditional weighted residuals (CWRES) greater than 5 to test for potential bias in parameter estimation and in covariate exploration. It concerned eight data points for six patients. Four observations were excluded for suspected error in administered dose, one observation for suspected error in time recording and one observation for suspected sampling bias. No obvious reason could explain high CWRES (6.3 and 5.8) associated with the two remaining observations and they were thus kept in the analysis. The sensitivity analysis showed that none of these concentration values affected the PK estimates (data not shown).

Parameters estimates, when scaled on BW, are reported for the median BW, i.e. 2170 g.

Model validation and simulation

The final model stability was assessed by the bootstrap method using the PsN-Toolkit [25] (version 3.5.3, Uppsala, Sweden). Mean parameter values with their 95% confidence interval (95% CI) estimated from 2000 re-sampled data sets were compared with the original model estimations. In addition, prediction-corrected visual predictive checks (pcVPC) [26] were performed with PsN-Toolkit and Xpose4 [27] (version 4.3.5, Uppsala, Sweden) by simulations based on the final PK estimates using 1000 individuals. Mean prediction-corrected concentrations with their 95% percentile interval (95% PI) at each time point were retrieved. Eventually, an independent set of 71 premature and term newborns recruited through TDM between January 2013 and April 2013 was employed for external model validation. From this external dataset, two individuals were excluded for an inconsistent dosing record. Population and individual post hoc concentrations were derived from the final model to assess the accuracy and the precision by means of the mean prediction error (MPE) and the root mean squared error (RMSE) [28], using log-transformed concentrations. Goodness-of-fit plots of population and individual predictions obtained in the final model vs. the observations were generated using R (version 2.15.1, R Development Core Team, Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Finally, observed and simulated concentrations were also compared by the normalized prediction distribution error (NPDE) method where each observation was simulated 3000 times (supporting information Figure S1).

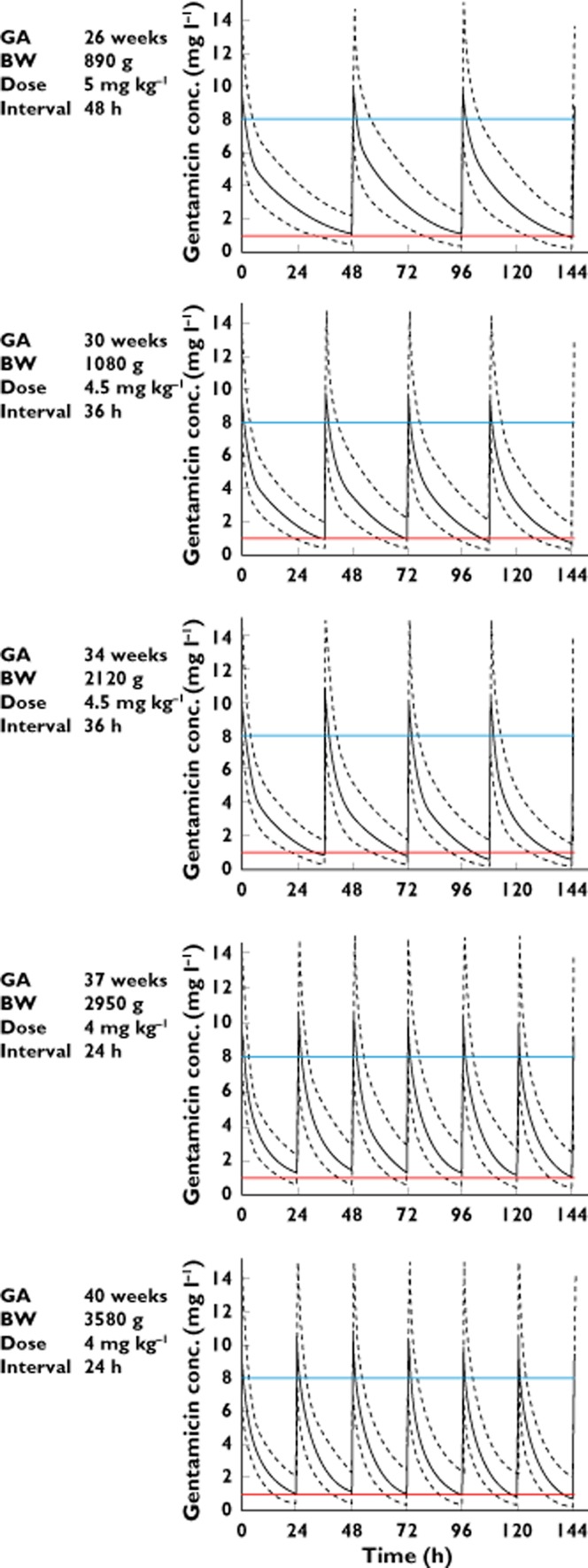

Average concentration−time profiles, with their 90% prediction interval (90% PI), were simulated for five representative patients (with a GA of 26, 30, 34, 37 and 40 weeks and a BW of 890, 1080, 2120, 2950 and 3580 g respectively, chosen as illustrative from the original dataset) using different dosage regimens, without dopamine co-administration. Dosage regimens evaluated were any combination of 4 mg kg−1, 4.5 mg kg−1 or 5 mg kg−1 any 24 h, 36 h or 48 h.

Comparison of dosage adjustment methods

The achievement of target concentrations was evaluated by comparing (i) dosing regimen recommendations based on the previously presented simulations and (ii) by TDM using the classical linear regression [23]. The external validation dataset was used for the comparison between both approaches. Peak and trough concentrations were predicted based on our final model (i) with dosing regimens adjusted for GA and BW according to our recommendations and (ii) based on individual dosage regimens derived from the linear regression method in the frame of TDM. Each set of patients was simulated 1000 times per method. For each set of patients simulated, the proportion of subjects meeting concentration targets at steady-state was retrieved. The mean with the 95% CI of the proportions were calculated.

Results

Gentamicin concentration data were collected from 1449 neonates, including 994 preterm (median gestational age 32 2/7 weeks, range 24 2/7–36 5/7 weeks) and 455 term newborns, representing a total of 1449 neonates who provided 3039 concentration measurements. A summary of the patients' characteristics for the model building and validation datasets is presented in Table 1. Peak concentrations represented 42% of samples (measured between 0.5 and 1.5 h after the start of infusion), while 40% were sampled about 12 h after the first dose (between 11.5 and 12.5 h after the start of infusion). Most drug measurements (86%) were performed after the first gentamicin dose and only 3% of concentrations were sampled beyond 72 h of treatment. The majority of the measurements (98%) were performed within the first week of life. Gentamicin concentration measurements ranged between 0.5 and 22.1 mg l−1 (one subject had a concentration of 29 mg l−1 because he received accidentally 10 times the usual prescribed dose).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the patients at treatment initiation

| Model-building set | External validation set | |

|---|---|---|

| n = 1449 | n = 69 | |

| BW (g) | 2170 (440–5510) | 2060 (600–4200) |

| GA (weeks) | 34 (24–42) | 34 (24–42) |

| PNA (days) | 1 (0–94) | 1 (0–34) |

| PMA (weeks) | 34.4 (24.2–42.4) | 34.2 (24.2–42.1) |

| Male | 834 (57.5%) | 38 (53.5%) |

| IV | 301 (20.8%) | 21 (30.4%) |

| NIV | 861 (59.4%) | 51 (73.9%) |

| PDA | 153 (10.6%) | 9 (13.0%) |

| Furosemide | 5 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Dopamine | 136 (9.4%) | 1 (1.4%) |

| Indomethacin | 27 (1.9%) | 2 (2.7%) |

| Amikacin | 2 (0.1%) | 0 (0%) |

Median (range) or count (percent). BW, body weight; GA, gestational age; IV, invasive ventilation; NIV, non-invasive ventilation; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; PMA, post-menstrual age; PNA, post-natal age.

Base model

A two compartment model parameterized in terms of clearance (CL), inter-compartmental CL (Q), volume of distribution of the central compartment (Vc) and peripheral volume of distribution (Vp) best described the data (ΔOF from the one compartment model was −280.0, P < 0.001). In addition to CL, an improvement of the fit was observed while including BSV on Vc (ΔOF = −252.8, P < 0.001) and a correlation of 87% was estimated between CL and Vc (ΔOF = −186.8, P < 0.001). Intrapatient variability was best described by a combined additive and proportional residual error model. The final base population parameters with their BSV were a CL of 0.087 l h−1 (CV 65%), a Vc of 0.825 l (CV 45%), a Q of 0.185 l h−1 and a Vp of 0.714 l. Additive and proportional residual error were 0.89 mg l−1 and 18%, respectively.

Covariate model

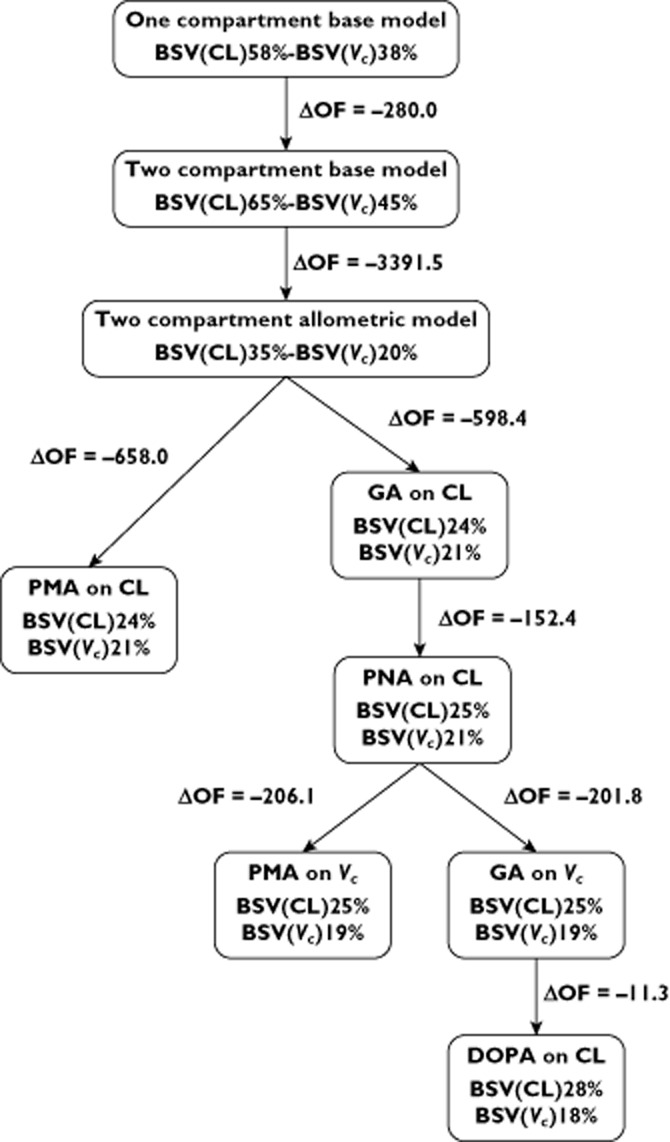

Figure 1 summarizes the model-building steps performed for the covariate analysis. The assignment of BW on CL, Vc, Q and Vp, following an allometric equation with a power of 0.75 on CL and Q and 1 on the volume parameters, markedly improved the description of the data (ΔOF = −3391.5, P < 0.001). The comparison of a one compartment allometric with a two compartment allometric model for BW showed that the latter provided a better fit of the data (supporting information Table S2). The use of a power function of 0.66 for BW on CL parameters was also investigated [29] but was significantly worse than the model with a power of 0.75 (ΔOF = 99.8, P < 0.001). Estimates of CL and Q increased by 68% whilst Vc and Vp on BW doubling increased by 100 %. This explained 45% of the inter-variability in CL and 55% in Vc. Owing to the very large effect of BW on these parameters, this variable was kept in the model for further covariates searches.

Figure 1.

Major steps of model building

The sequential addition of GA, PNA and PMA using a linear function on CL and Vc resulted in a better description of the data. PMA was the most important covariate on CL (ΔOF = −658.1, P < 0.001) and on Vc (ΔOF = −214.6, P < 0.001).

Since PMA is the sum of GA and PNA, we searched which combination of these latter variables provided the best description of the data. Comparing PMA with GA + PNA on CL showed a significant drop in the OF value (ΔOF = −750.8 P < 0.001) in favour of the model with the two distinct covariates GA and PNA.

PMA was slightly more significant than GA on Vc (ΔOF = −206.1 for PMA compared with ΔOF = −201.8 for GA, P < 0.001 with the AIC difference between the two models 4.3 points in favour of PMA). However, PNA did not show any influence on Vc in the univariate analysis (ΔOF = −1.9, P = 0.16). Following the parsimony principle, GA alone was preferred to PMA as a covariate on Vc. Eventually, PMA was also retested in the final model in replacement of GA, confirming that it was not a better predictor than GA (ΔOF = 0.14, P = 0.70, and AIC was 1964 for both models).

CL was reduced by 12% and 18% by co-administration of dopamine (ΔOF = −11.3, P < 0.001) and indomethacin (ΔOF = −7.8, P = 0.005), respectively. Although not statistically significant, furosemide co-administration reduced CL by 34% (ΔOF = −6.3, P = 0.012). No other covariates showed any significant effect on gentamicin disposition (ΔOF > −6.1, P > 0.01).

Model validation and simulation

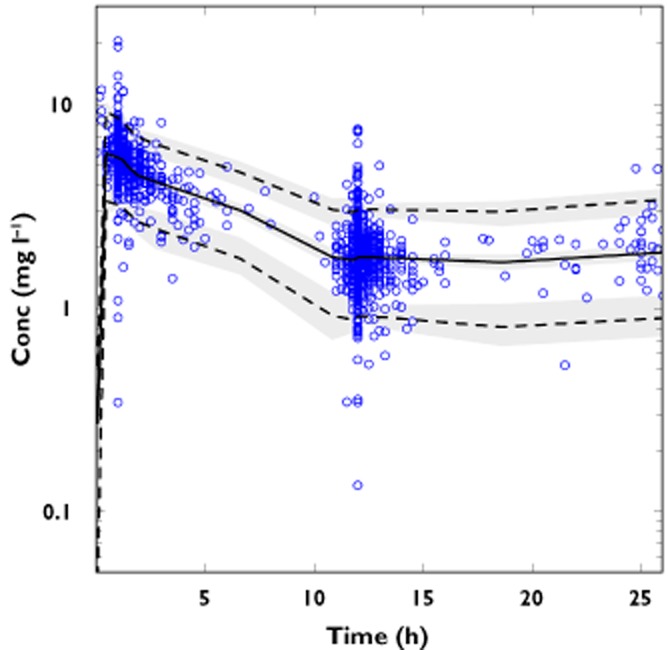

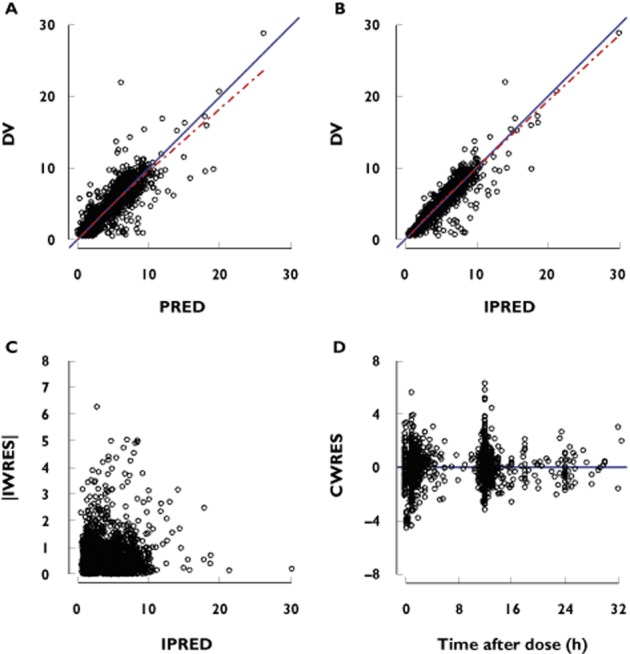

The parameter estimates of the final population PK model, except for indomethacin, remained within the bootstrap 95% CI and differed by less than 9% from the median parameters obtained with the bootstrap analysis, suggesting that the model was acceptable. Since the indomethacin coefficient 95% CI included 0, it was omitted from the final model. It appeared that it did not affect the model as the relative difference in parameter estimates between the model with and without indomethacin was less than 3% (data not shown). The structural and the final model parameter estimates as well as the bootstrap are presented in Table 2. The results of pcVPC supported the predictive performance of the model and are presented in Figure 2. Goodness-of-fit plots are presented in Figure 3. The external validation showed a small bias of −3% (95% CI −1, −4%) in the individual predictions, with an imprecision of 12% (supporting information Figure S3). A similar bias of −6% (95% CI −3, −9%) was calculated for population predictions, with an imprecision of 22%. Only one patient received dopamine among the newborns of the validation dataset.

Table 2.

Parameter estimation of structural and final pharmacokinetic models, with final model associated bootstraps

| Parameters | Structural model | Final model | Final model bootstrap (n = 2000 samples) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimates | SE (%) | Estimates§ | SE (%) | Estimates§ | CI (2.5%) | CI (97.5%) | |

| CL (l h−1) | 0.087 | 1* | 0.089 | 1* | 0.089 | 0.084 | 0.098 |

| θCLBW | 0.75 | – | 0.75 | – | – | ||

| θCLGA | 1.870 | 3 * | 1.879 | 1.638 | 2.010 | ||

| θCLPNA | 0.054 | 6 * | 0.054 | 0.024 | 0.082 | ||

| θCLDOPA | −0.120 | 22 * | −0.118 | −0.198 | −0.034 | ||

| Vc (l) | 0.825 | 1 * | 0.908 | 2 * | 0.895 | 0.481 | 0.950 |

| θVcBW | 1 | – | 1 | – | – | ||

| θVcGA | −0.922 | 8 * | −0.940 | −2.276 | −0.816 | ||

| Q (l h−1) | 0.185 | 9 * | 0.157 | 7 * | 0.172 | 0.108 | 0.737 |

| θQBW | 0.75 | – | 0.75 | – | – | ||

| Vp (l) | 0.714 | 16 * | 0.560 | 4 * | 0.580 | 0.472 | 0.678 |

| θVpBW | 1 | – | 1 | – | – | ||

| BSV CL (%) | 65 | 5 † | 28 | 3 † | 28 | 22 | 30 |

| BSV Vc (%) | 45 | 5 † | 18 | 1 † | 19 | 12 | 39 |

| Correlation CL-Vc (%) | 87 | 3‡ | 86 | 54 | 111 | ||

| Additive residual error (mg l−1) | 0.89 | 14 | 0.10 | 24 * | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.19 |

| Proportional residual error (%) | 18 | 11 | 18 | 1 * | 18 | 16 | 19 |

Standard errors of the estimates (SE),defined as SE/estimate and expressed as percentages.

Standard errors of the coefficient of variation, taken as SE / (Estimates × 2) and expressed as percentage.

Standard error of the correlation estimate directly retrieved from the nonmem® output file and expressed as percentages. BSV, between subject variability; BW, body weight; CL, clearance; DOPA, dopamine; GA, gestational age; PNA, post-natal age; Q, inter-compartmental clearance; Vc, central volume of distribution; Vp, peripheral volume of distribution.

Value estimates for the median body weight 2.170 kg from the current study.

Figure 2.

Prediction-corrected visual predictive check of the final model with gentamicin prediction-corrected concentrations (circles) and population prediction (solid line) with the corresponding 95% prediction interval (dotted lines). Semi-transparent grey fields represent the model-based percentile confidence interval

Figure 3.

Goodness-of-fit plots of observations (DV) vs. the population (PRED, A) and individual predictions (IPRED, B), absolute individual weighted residuals (|IWRES|) vs. IPRED (C) and conditional weighted residuals (CWRES) vs. time after dose (D). The solid line represents the line of identity while the dashed line represents the smoothing line

Average concentration−time profiles for the different GAs and dosing schedules are presented in Figure 4. These results confirm that higher doses and longer dosage intervals are needed in very preterm newborns compared with term infants to reach target concentrations (Cmin ≤ 1 mg l−1 and Cmax ≈ 8 mg l−1). The dosing recommendations that came forth from these simulations were identical to those proposed by reference drug guidelines used in neonatology, namely 5 mg kg−1 every 48 h for GA ≤ 29 weeks, 4.5 mg kg−1 every 36 h for 30 ≤ GA ≤ 34 and 4 mg kg−1 every 24 h in the first days of life [30].

Figure 4.

Model-based predicted concentration−time profiles (solid line) and the 90% prediction interval (dotted lines) for five gestational ages and body weights using the dosage regimen allowing target concentration to be reached (Cmin ≤ 1 mg l−1 and Cmax approximately 8 mg l−1). GA = gestational age, BW = body weight

Comparison of dosage adjustment methods

Table 3 presents the proportion of subjects reaching target trough and peak concentrations at steady state, according to both methods (i.e. the guidelines and the two point linear regression). One subject was excluded because the C12h concentration was missing and the dosage adjustment using the two points approach could not be performed. A broader range of target concentrations was also considered in this comparison to account for different thresholds proposed in the literature (trough concentration <2 mg l−1 and peak concentration between 5–12 mg l−1 [31,32]). This analysis reveals that the application of guidelines would lead to similar, if not better results in terms of target achievement of peak and trough concentrations than the linear regression based on a systematic TDM.

Table 3.

Model-based simulated proportion of patients reaching target concentration according to dosing adjustment method

| GA (weeks) | BW (g) | <1 mg l−1 (% [95% CI]) | <2 mg l−1 (% [95% CI]) | >6 mg l−1 (% [95% CI]) | >8 mg l−1 (% [95% CI]) | >10 mg l−1 (% [95% CI]) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guidelines | Linear regression | Guidelines | Linear regression | Guidelines | Linear regression | Guidelines | Linear regression | Guidelines | Linear regression | ||

| 24–42 n = 68 |

600–4200 | 64 [52, 73] |

42 [32, 52] |

94 [89, 99] |

82 [73, 89] |

93 [86, 99] |

83 [75, 91] |

69 [58, 79] |

55 [45, 65] |

37 [26, 49] |

28 [18, 38] |

BW, body weight; GA, gestational age.

Guidelines were as follows:

GA ≤ 29 weeks 5 mg kg−1 every 48 h

30 ≤ GA ≤ 34 weeks 4.5 mg kg−1 every 36 h

GA ≥ 35 weeks 4 mg kg−1 every 24 h

Linear regression provides an individualized dosing regimen based on a two points method.

Results are based on a small group of 68 patients who were simulated 1000 times each according to both methods of dosing adjustment.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest study evaluating the population PK of gentamicin in a cohort of unselected neonates covering a wide range of body weight and gestational age.

The PK of gentamicin has been previously described using one [33–46] two [47–50] and three [51,52] exponential disposition terms, which probably illustrate the deep compartments and tissue accumulation of gentamicin. Our PK estimates of CL and Vc are in good accordance with previously published studies in a similar population [34,35,37,38,44,46]. The half-life of the terminal phase was estimated to be 12.5 h, much lower than the values derived by others based on three compartment models (87 to 173 h [48], 27 to 693 h [49], 94 h [51] in adults and 425 h [52] in neonates). This discrepancy is most probably related to differences in study design, with short treatment courses and lack of gentamicin concentration measurements beyond 72 h, preventing adequate characterization of the slowest distribution component of the drug in peripheral tissues and thus, of a third exponential term.

Description of gentamicin PK confirmed that the primary factors influencing newborns' exposure are size and age (BW, GA and PNA) [53].

Gentamicin is a hydrophilic drug that is rapidly and predominantly distributed into extracellular fluid. Extracellular fluid represents approximately 65% of BW at 35 weeks of gestation and falls to 40% at term [16]. At the same time, fat mass and intracellular water increase. Decrease in body water also continues after birth and extracellular fluid becomes closely related to BW [54], supporting our observations of an effect of body weight on Vc.

Gentamicin CL increases with age. Because renal maturation progresses before birth [18], it was advocated that PMA would be a better predictor than PNA [53,55,56]. In the present study, PMA was found to be a good predictor of gentamicin CL, but the use of GA and PNA described gentamicin disposition better than PMA alone. Our results are in excellent agreement with the study of Nielsen et al. [52], who found an influence of both GA and PNA on CL and GA on Vc.

Dopamine was found to be a relevant factor associated with a 12% decrease in CL. The impact of dopamine on GFR in neonates is not well documented [57–59] and, has never been observed for gentamicin in others studies. Only a few patients were treated with dopamine (9%). Its influence on gentamicin elimination appears small and of limited clinical significance in this analysis. It might principally reflect cardiovascular instability in critically ill newborns.

Several studies have shown the potential effect of ibuprofen and indomethacin on glomerular filtration reflected by a reduction of renal excretion of drugs such as aminoglycosides [15,42,60–62]. Our results also suggest an influence of indomethacin on gentamicin CL, although this effect was not validated. The small number of patients (n = 27) might have limited the power to detect a true effect. It is also possible that confounding factors were reflected this way, since those newborns had a very low body weight, (mean 852 g, range 440–1390 g), as well as haemodynamically significant PDA, which is associated with poor renal perfusion [63]. Even so, PDA had no significant impact on CL per se in this analysis. Furosemide was not found to significantly reduce gentamicin CL, as opposed to one study which suggested an increase in gentamicin concentrations as a result of furosemide co-administration [64]. Only five patients received it, four of whom were on concomittant dopamine treatment. This might have limited the possibility to detect an independent effect of furosemide. In addition, some studies found a relation between respiratory disorders or invasive and non-invasive ventilation with gentamicin CL or V [34,65,66]. No influence of respiratory support on gentamicin kinetics was observed in our study.

Several limitations of this analysis should be acknowledged, in particular the use of routine TDM data involving for the most part only two concentration measurements collected after the first dose, thus limiting the possibility to characterize deep compartment kinetics. In addition, due to the retrospective design, errors coming from inaccurate times or dosage recording could not be systematically traced and corrected.

Model-based simulations suggest that most infants born at a GA above 34 weeks are expected to reach target concentrations (peak above 8 mg l−1 and Cmin below 1 mg l−1 [67,68]) with a standard dosage of 4 mg kg−1 once daily. Preterm neonates require longer dosing intervals, up to 48 h and extremely preterm neonates (below 28 weeks of GA) will also require higher doses of 5 mg kg−1. These observations are in accordance with dosing recommendations issued since the mid-1990s [31,69] that advocate high doses and extended intervals to reach sufficient peak concentrations whilst minimizing toxicity. Proposed dosing regimens were designed assuming fixed values of concentration thresholds for effect and toxicity, in accordance with numerous studies demonstrating the importance of a high ratio Cmax : MIC for aminoglycosides. One study suggested that the area under the curve (AUC) might be of clinical importance for extreme preterm newborns [70]. Target concentrations can also be challenged, as adaptive resistance can arise within the first hours of therapy, probably through a down regulation of the active transport of gentamicin into the bacteria. The use of extended interval dosing seems thus preferable to improve clinical efficacy, as it allows adaptive resistance to resolve while taking advantage of the post-antibiotic effect [31,70,71].

Considering that a priori dosage regimen recommendations [30] appear appropriate to ensure effective and safe concentration exposure, and that most gentamicin treatments will be stopped after 48 h, TDM has a limited role at treatment initiation in this population. However, the use of TDM to optimize target achievement will still be needed for some patients, since a large variability in drug exposure remains after adjustment for age and body weight, and a proportion of patients will still fail to reach adequate PK targets. This should be particularly considered for those patients receiving prolonged treatment.

In conclusion gentamicin kinetics in newborns are very variable and mostly dependent on growth status (represented by BW) and maturation (represented by GA and PNA). The influence of comedications, such as dopamine, as direct or indirect factors influencing renal function should be confirmed. Recent dosing recommendations showed a benefit in terms of target concentration achievement and reduction of TDM need at treatment initiation. Our model will serve to elaborate a Bayesian tool for dosage individualization based on a single measurement [72], that could be ideally suited for dosage individualization of neonates at particular risk of sub-optimal dosing during prolonged therapy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation through the Nano-Tera initiative. The corresponding project (ISyPeM) involves the implementation of software for Bayesian therapeutic drug monitoring. The authors thank Jocelyne Urfer and David Jenny for data management. The authors are also thankful to Sonja Roetlisberger for the careful reading of the manuscript.

Competing Interests

All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare our institution has support from the Swiss National Science Foundation through the Nano-Tera initiative (the corresponding project, ISyPeM, involves the implementation of software for Bayesian therapeutic drug monitoring) for the submitted work, no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Author contributions

Study concepts: CC

Acquisition of data: AF, DW, CG

Analysis supervision: CC, AW, TB

Analysis and interpretation of data: AF, MG

Clinical interpretation and input: AG, NW

Drafting of the manuscript: AF

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web-site:

Figure S1 Distribution of the normalized prediction distribution error (NPDE) method. (A) Histograms of the distribution of the NPDE and the solid line representing the normal distribution. Distribution of the NPDE (B) vs. time and (C) vs. predicted concentrations

Figure S2 Individual gentamicin predicted concentrations vs. observed concentrations (circles) with the smoothed relationship (dotted line) from the final model from the external validation dataset

Table S1 Parameter estimation of one compartment allometric model and two compartment allometric model

References

- 1.Lopez-Novoa JM, Quiros Y, Vicente L, Morales AI, Lopez-Hernandez FJ. New insights into the mechanism of aminoglycoside nephrotoxicity: an integrative point of view. Kidney Int. 2011;79:33–45. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schultze RG, Winters RE, Kauffman H. Possible nephrotoxicity of gentamicin. J Infect Dis. 1971;124(Suppl):S145–147. doi: 10.1093/infdis/124.supplement_1.s145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilfert JN, Burke JP, Bloomer HA, Smith CB. Renal insufficiency associated with gentamicin therapy. J Infect Dis. 1971;124(Suppl):S148–155. doi: 10.1093/infdis/124.supplement_1.s148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banck G, Belfrage S, Juhlin I, Nordstrom L, Tjernstrom O, Toremalm NG. Retrospective study of the ototoxicity of gentamicin. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand B Microbiol Immunol. 1973;(Suppl. 241):54–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borradori C, Fawer CL, Buclin T, Calame A. Risk factors of sensorineural hearing loss in preterm infants. Biol Neonate. 1997;71:1–10. doi: 10.1159/000244391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Polin RA Committee on F, Newborn. Management of neonates with suspected or proven early-onset bacterial sepsis. Pediatrics. 2012;129:1006–1015. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stocker M, Berger C, McDougall J, Giannoni E. Taskforce for the Swiss Society of N, the Paediatric Infectious Disease Group of S. Recommendations for term and late preterm infants at risk for perinatal bacterial infection. Swiss Med Wkly. 2013;143:w13873. doi: 10.4414/smw.2013.13873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pagkalis S, Mantadakis E, Mavros MN, Ammari C, Falagas ME. Pharmacological considerations for the proper clinical use of aminoglycosides. Drugs. 2011;71:2277–2294. doi: 10.2165/11597020-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bailey DN, Briggs JR. Gentamicin and tobramycin binding to human serum in vitro. J Anal Toxicol. 2004;28:187–189. doi: 10.1093/jat/28.3.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gordon RC, Regamey C, Kirby WM. Serum protein binding of the aminoglycoside antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1972;2:214–216. doi: 10.1128/aac.2.3.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riff LJ, Jackson GG. Pharmacology of gentamicin in man. J Infect Dis. 1971;124(Suppl):S98–105. doi: 10.1093/infdis/124.supplement_1.s98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Black MJ, Sutherland MR, Gubhaju L, Kent AL, Dahlstrom JE, Moore L. When birth comes early: effects on nephrogenesis. Nephrology (Carlton) 2013;18:180–182. doi: 10.1111/nep.12028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guignard JP, Drukker A. Why do newborn infants have a high plasma creatinine? Pediatrics. 1999;103:e49. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.4.e49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kyser KL, Morriss FH, Jr, Bell EF, Klein JM, Dagle JM. Improving survival of extremely preterm infants born between 22 and 25 weeks of gestation. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:795–800. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31824b1a03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cuzzolin L, Fanos V, Pinna B, di Marzio M, Perin M, Tramontozzi P, Tonetto P, Cataldi L. Postnatal renal function in preterm newborns: a role of diseases, drugs and therapeutic interventions. Pediatr Nephrol. 2006;21:931–938. doi: 10.1007/s00467-006-0118-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Besunder JB, Reed MD, Blumer JL. Principles of drug biodisposition in the neonate. A critical evaluation of the pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic interface (Part II) Clin Pharmacokinet. 1988;14:261–286. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198814050-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friis-Hansen B. Body water compartments in children: changes during growth and related changes in body composition. Pediatrics. 1961;28:169–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kearns GL, Abdel-Rahman SM, Alander SW, Blowey DL, Leeder JS, Kauffman RE. Developmental pharmacology - drug disposition, action, and therapy in infants and children. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1157–1167. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheiner LB, Beal S, Rosenberg B, Marathe VV. Forecasting individual pharmacokinetics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1979;26:294–305. doi: 10.1002/cpt1979263294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pons G, Treluyer JM, Dimet J, Merle Y. Potential benefit of Bayesian forecasting for therapeutic drug monitoring in neonates. Ther Drug Monit. 2002;24:9–14. doi: 10.1097/00007691-200202000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Touw DJ, Westerman EM, Sprij AJ. Therapeutic drug monitoring of aminoglycosides in neonates. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2009;48:71–88. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200948020-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fuchs A, Csajka C, Thoma Y, Buclin T, Widmer N. Benchmarking therapeutic drug monitoring software: a review of available computer tools. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2013;52:9–22. doi: 10.1007/s40262-012-0020-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sawchuk RJ, Zaske DE, Cipolle RJ, Wargin WA, Strate RG. Kinetic model for gentamicin dosing with the use of individual patient parameters. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1977;21:362–369. doi: 10.1002/cpt1977213362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holford NH. A size standard for pharmacokinetics. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1996;30:329–332. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199630050-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindbom L, Pihlgren P, PsN JEN. Toolkit - a collection of computer intensive statistical methods for non-linear mixed effect modeling using NONMEM. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2005;79:241–257. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bergstrand M, Hooker AC, Wallin JE, Karlsson MO. Prediction-corrected visual predictive checks for diagnosing nonlinear mixed-effects models. AAPS J. 2011;13:143–151. doi: 10.1208/s12248-011-9255-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jonsson EN, Karlsson MO. Xpose–an S-PLUS based population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model building aid for NONMEM. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 1999;58:51–64. doi: 10.1016/s0169-2607(98)00067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheiner LB, Beal SL. Some suggestions for measuring predictive performance. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1981;9:503–512. doi: 10.1007/BF01060893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McLeay SC, Morrish GA, Kirkpatrick CM, Green B. The relationship between drug clearance and body size: systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature published from 2000 to 2007. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2012;51:319–330. doi: 10.2165/11598930-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Young TE, Mangum B. Neofax. 24th edn. Montvale, NJ: Physician Desk Reference Inc; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Young TE. Aminoglycoside therapy in neonates : with particular reference to gentamicin. Neoreviews. 2002;3:e243–248. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rao SC, Srinivasjois R, Hagan R, Ahmed M. One dose per day compared to multiple doses per day of gentamicin for treatment of suspected or proven sepsis in neonates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(11) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005091.pub3. )CD005091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelman AW, Thomson AH, Whiting B, Bryson SM, Steedman DA, Mawer GE, Samba-Donga LA. Estimation of gentamicin clearance and volume of distribution in neonates and young children. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1984;18:685–692. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1984.tb02530.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomson AH, Way S, Bryson SM, McGovern EM, Kelman AW, Whiting B. Population pharmacokinetics of gentamicin in neonates. Dev Pharmacol Ther. 1988;11:173–179. doi: 10.1159/000457685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Izquierdo M, Lanao JM, Cervero L, Jimenez NV, Dominguez-Gil A. Population pharmacokinetics of gentamicin in premature infants. Ther Drug Monit. 1992;14:177–183. doi: 10.1097/00007691-199206000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weber W, Kewitz G, Rost KL, Looby M, Nitz M, Harnisch L. Population kinetics of gentamicin in neonates. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1993;44(Suppl. 1):S23–25. doi: 10.1007/BF01428387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jensen PD, Edgren BE, Brundage RC. Population pharmacokinetics of gentamicin in neonates using a nonlinear, mixed-effects model. Pharmacotherapy. 1992;12:178–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rocha MJ, Almeida AM, Afonso E, Martins V, Santos J, Leitao F, Falcao AC. The kinetic profile of gentamicin in premature neonates. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2000;52:1091–1097. doi: 10.1211/0022357001775010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stickland MD, Kirkpatrick CM, Begg EJ, Duffull SB, Oddie SJ, Darlow BA. An extended interval dosing method for gentamicin in neonates. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001;48:887–893. doi: 10.1093/jac/48.6.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stolk LM, Degraeuwe PL, Nieman FH, de Wolf MC, de Boer A. Population pharmacokinetics and relationship between demographic and clinical variables and pharmacokinetics of gentamicin in neonates. Ther Drug Monit. 2002;24:527–531. doi: 10.1097/00007691-200208000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Botha JH, du Preez MJ, Adhikari M. Population pharmacokinetics of gentamicin in South African newborns. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;59:755–759. doi: 10.1007/s00228-003-0663-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.DiCenzo R, Forrest A, Slish JC, Cole C, Guillet R. A gentamicin pharmacokinetic population model and once-daily dosing algorithm for neonates. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23:585–591. doi: 10.1592/phco.23.5.585.32196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lanao JM, Calvo MV, Mesa JA, Martin-Suarez A, Carbajosa MT, Miguelez F, Dominguez-Gil A. Pharmacokinetic basis for the use of extended interval dosage regimens of gentamicin in neonates. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;54:193–198. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lingvall M, Reith D, Broadbent R. The effect of sepsis upon gentamicin pharmacokinetics in neonates. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;59:54–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02260.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garcia B, Barcia E, Perez F, Molina IT. Population pharmacokinetics of gentamicin in premature newborns. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;58:372–379. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sherwin CM, Kostan E, Broadbent RS, Medlicott NJ, Reith DM. Evaluation of the effect of intravenous volume expanders upon the volume of distribution of gentamicin in septic neonates. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 2009;30:276–280. doi: 10.1002/bdd.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Adelman M, Evans E, Schentag JJ. Two-compartment comparison of gentamicin and tobramycin in normal volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1982;22:800–804. doi: 10.1128/aac.22.5.800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schentag JJ, Jusko WJ. Renal clearance and tissue accumulation of gentamicin. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1977;22:364–370. doi: 10.1002/cpt1977223364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schentag JJ, Jusko WJ, Plaut ME, Cumbo TJ, Vance JW, Abrutyn E. Tissue persistence of gentamicin in man. JAMA. 1977;238:327–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lopez SA, Mulla H, Durward A, Tibby SM. Extended-interval gentamicin: population pharmacokinetics in pediatric critical illness. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2010;11:267–274. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181b80693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Laskin OL, Longstreth JA, Smith CR, Lietman PS. Netilmicin and gentamicin multidose kinetics in normal subjects. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1983;34:644–650. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1983.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nielsen EI, Sandstrom M, Honore PH, Ewald U, Friberg LE. Developmental pharmacokinetics of gentamicin in preterm and term neonates: population modelling of a prospective study. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2009;48:253–263. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200948040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Anderson BJ, Allegaert K, Holford NH. Population clinical pharmacology of children: modelling covariate effects. Eur J Pediatr. 2006;165:819–829. doi: 10.1007/s00431-006-0189-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Besunder JB, Reed MD, Blumer JL. Principles of drug biodisposition in the neonate. A critical evaluation of the pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic interface (Part I) Clin Pharmacokinet. 1988;14:189–216. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198814040-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rhodin MM, Anderson BJ, Peters AM, Coulthard MG, Wilkins B, Cole M, Chatelut E, Grubb A, Veal GJ, Keir MJ, Holford NH. Human renal function maturation: a quantitative description using weight and postmenstrual age. Pediatr Nephrol. 2009;24:67–76. doi: 10.1007/s00467-008-0997-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Anderson BJ, Allegaert K, Van den Anker JN, Cossey V, Holford NH. Vancomycin pharmacokinetics in preterm neonates and the prediction of adult clearance. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63:75–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02725.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barrington K, Brion LP. Dopamine versus no treatment to prevent renal dysfunction in indomethacin-treated preterm newborn infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003213. )CD003213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Seri I, Rudas G, Bors Z, Kanyicska B, Tulassay T. Effects of low-dose dopamine infusion on cardiovascular and renal functions, cerebral blood flow, and plasma catecholamine levels in sick preterm neonates. Pediatr Res. 1993;34:742–749. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199312000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lynch SK, Lemley KV, Polak MJ. The effect of dopamine on glomerular filtration rate in normotensive, oliguric premature neonates. Pediatr Nephrol. 2003;18:649–652. doi: 10.1007/s00467-003-1148-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.De Cock RF, Allegaert K, Schreuder MF, Sherwin CM, de Hoog M, van den Anker JN, Danhof M, Knibbe CA. Maturation of the glomerular filtration rate in neonates, as reflected by amikacin clearance. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2012;51:105–117. doi: 10.2165/11595640-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Allegaert K, Rayyan M, Anderson BJ. Impact of ibuprofen administration on renal drug clearance in the first weeks of life. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 2006;28:519–522. doi: 10.1358/mf.2006.28.8.1037489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van den Anker JN, Hop WC, de Groot R, van der Heijden BJ, Broerse HM, Lindemans J, Sauer PJ. Effects of prenatal exposure to betamethasone and indomethacin on the glomerular filtration rate in the preterm infant. Pediatr Res. 1994;36:578–581. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199411000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mercanti I, Boubred F, Simeoni U. Therapeutic closure of the ductus arteriosus: benefits and limitations. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;22(Suppl. 3):14–20. doi: 10.1080/14767050903198132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lawson DH, Tilstone WJ, Gray JM, Srivastava PK. Effect of furosemide on the pharmacokinetics of gentamicin in patients. J Clin Pharmacol. 1982;22:254–258. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1982.tb02670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bhatt-Mehta V, Donn SM. Gentamicin pharmacokinetics in term newborn infants receiving high-frequency oscillatory ventilation or conventional mechanical ventilation: a case-controlled study. J Perinatol. 2003;23:559–562. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7210985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Triginer C, Izquierdo I, Fernandez R, Torrent J, Benito S, Net A, Jane F. Changes in gentamicin pharmacokinetic profiles induced by mechanical ventilation. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;40:297–302. doi: 10.1007/BF00315213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pacifici GM. Clinical pharmacokinetics of aminoglycosides in the neonate: a review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65:419–427. doi: 10.1007/s00228-008-0599-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Turnidge J. Pharmacodynamics and dosing of aminoglycosides. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003;17:503–528. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(03)00057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chattopadhyay B. Newborns and gentamicin–how much and how often? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002;49:13–16. doi: 10.1093/jac/49.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mohamed AF, Nielsen EI, Cars O, Friberg LE. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic model for gentamicin and its adaptive resistance with predictions of dosing schedules in newborn infants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:179–188. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00694-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Barclay ML, Begg EJ. Aminoglycoside adaptive resistance: importance for effective dosage regimens. Drugs. 2001;61:713–721. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200161060-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.EzeCHiel. 2013. [online]. Yverdon-Lausanne: ISyPeM Project Jun; Available at http://www.ezechiel.ch/ (last accessed 21 March 2014)

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Distribution of the normalized prediction distribution error (NPDE) method. (A) Histograms of the distribution of the NPDE and the solid line representing the normal distribution. Distribution of the NPDE (B) vs. time and (C) vs. predicted concentrations

Figure S2 Individual gentamicin predicted concentrations vs. observed concentrations (circles) with the smoothed relationship (dotted line) from the final model from the external validation dataset

Table S1 Parameter estimation of one compartment allometric model and two compartment allometric model