Abstract

Aims

Medication reviews by a third party have been introduced as a method to improve drug treatment in older people. We assessed whether this intervention reduces mortality and hospitalization for nursing home residents.

Methods

Systematic literature searches were performed (from January 1990 to June 2012) in Medline, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, ProQuest Nursing & Allied Health Sources and Health Technology Assessment databases. We included randomized and nonrandomized controlled trials (RCTs and non-RCTs) of medication reviews compared with standard care or other types of medication reviews in nursing home residents. The outcome variables were mortality and hospitalization. Study quality was assessed systematically. We performed meta-analyses using random-effects models.

Results

Seven RCTs and five non-RCTs fulfilled the inclusion criteria. The mean age of included patients varied between 78 and 86 years. They were treated with a mean of 4–12 drugs. The study quality was assessed as high (n = 1), moderate (n = 4) or low (n = 7). Eight studies compared medication reviews with standard care. In six of them, pharmacists were involved in the intervention. Meta-analyses of RCTs revealed a risk ratio (RR) for mortality of 1.03 [medication reviews vs. standard care; five trials; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.85–1.23]. The corresponding RR for hospitalization was 1.07 (two trials; 95% CI 0.61–1.87).

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that medication reviews for nursing home residents do not reduce mortality or hospitalization. More research in the setting of controlled trials remains to be done in order to clarify how drug treatment can be optimized for these patients.

Keywords: drug treatment, medication review, nursing home

Introduction

Drug treatment in older people, with multiple diseases and long medication lists, is a challenge. In clinical practice, suboptimal pharmacotherapy is common; for example, treatment with inappropriate drugs or dosages and/or omissions of drugs from which the patient would probably benefit 1. Indeed, up to ∼50% of hospital admissions have been reported to be drug related 2. Furthermore, adverse drug reactions cause a substantial number of deaths each year 3. This drug-related morbidity and mortality has received attention not only from healthcare professionals, but also from authorities and regulators.

Medication reviews have been proposed, and introduced, as a method to improve prescribing practices. This intervention is based on a systematic assessment, based on varying sources of patient information 4, with the aim of evaluating and optimizing the drug treatment. Commonly, medication reviews are performed by a third party not directly responsible for the patients. Pharmacists are often involved, either alone or in multiprofessional teams. A medication review may include medication reconciliation, i.e. to identify the most accurate list of medications for a patient. The main contribution, however, is often to assess the appropriateness of the pharmacotherapy; for example, according to general recommendations or with the use of indicators such as the Medication Appropriateness Index (MAI) 5 or Beers criteria 6.

For interventions in healthcare, evidence on a net positive balance between benefits and harms is essential. Preferably, such evidence should include hard end-points, i.e. patient-relevant outcomes. A systematic review on the effect of medication reviews on such outcomes was published in 2008 7. It reported that medication reviews did not significantly affect mortality and hospitalizations. Several new studies have been published in the last 5 years. An update of the documentation on the effects of medication reviews on these important outcomes is therefore needed. A recent Cochrane review concluded that it is uncertain whether medication reviews in hospitalized patients reduce subsequent mortality or hospital admissions 8. Furthermore, another recent Cochrane review, which evaluated all kinds of interventions for optimized prescribing for patients in care homes, did not find evidence for an effect on resident-related outcomes 9. The former review provided pooled risk estimates on the effects of medication reviews on mortality and hospitalization, whereas the latter review did not. Neither of the reviews included nonrandomized controlled trials (non-RCTs). Therefore, we undertook this systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate further whether medication reviews can reduce mortality and hospitalization in nursing home residents.

Methods

We performed a systematic review according to established routines at the Regional Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Centre in the Region Västra Götaland, Sweden. The PICO was defined as follows. Patients (P) were nursing home residents with drug treatment. Intervention (I) was medication review. Comparison (C) was standard care or other type of medication review. Outcomes (O) were mortality and hospitalization. A medication review was defined as any kind of systematic assessment of a patient’s medications with the aim to evaluate and optimize his or her drug treatment. We included both randomized (RCTs) and nonrandomized controlled trials and restricted the publications to English or Scandinavian languages (Swedish, Danish and Norwegian). Furthermore, we allowed randomization at the individual as well as at the aggregated level. Studies in which the medication review was focused on a specific condition or a specific class of drugs were excluded.

Literature search

Systematic searches, covering the period from January 1990 to June 2012, were performed in Medline, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, ProQuest Nursing & Allied Health Sources and Health Technology Assessment databases. We also searched the reference lists of included articles. A detailed description of the search strategies is available in Appendix S1. In order to identify ongoing or completed, but still not published, studies we searched http://www.clinicaltrials.gov, http://www.controlled-trials.com and http://www.who.int/ictrp/en (last accessed 7 January 2014).

Study selection

Two research librarians screened all the identified abstracts and, if needed, also read the full-text articles. Those that did not fulfil the PICO were excluded. All the remaining studies were independently assessed for eligibility by all authors, followed by a consensus discussion for final inclusion in the systematic review.

Data extraction

Data were extracted from the studies by one investigator (SMW) and subsequently checked by two others (JMK and KN). The data extracted included the number of individuals in the intervention and the control groups, type of intervention (including classification into one of three types of medication reviews according to the National Prescribing Centre 4) and comparison, length of follow-up, the defined primary end-point of the specific study, and data on mortality and hospitalizations. When numbers on included, deceased and/or hospitalized individuals were not reported in the RCTs, we sent a request e-mail to the corresponding author.

Quality assessment

The study quality was independently assessed by four investigators (SMW, JMK, KN and AS) according to checklists used by the HTA Centre 10. These include assessments on directness (external validity), risk of bias (internal validity) and precision. The investigators discussed the assessments and set the overall study quality to high, moderate or low. Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Statistical analyses

Randomized controlled trials that compared medication reviews with standard care and provided relevant numbers in the publication were pooled in meta-analyses concerning all-cause mortality and hospitalizations using the software Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.1 (The Cochrane Collaboration, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). The Mantel–Haenszel method was applied in a random-effects model. Risk ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. We did not assess publication bias with funnel plots because we considered the number of studies included in the meta-analyses too few for this purpose. Heterogeneity was measured with the I2 statistic. In the meta-analysis of mortality, two studies of low scientific quality had a great number of patients and, as a consequence, contributed to a large extent to the pooled result. Therefore, as meta-analyses of studies with questionable quality can be hard to interpret 11, we also performed a sensitivity meta-analysis without the low-quality studies. No other sensitivity analyses were performed.

Results

Study selection

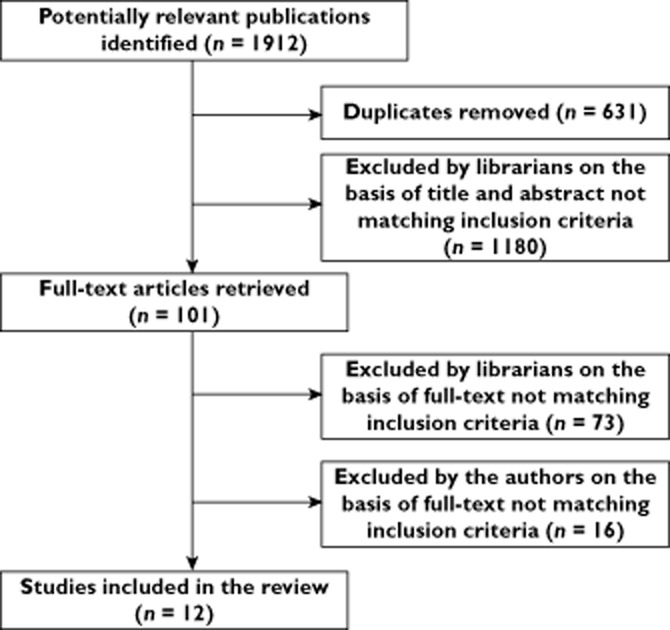

After removal of duplicates, 1281 unique references were identified. The librarians first excluded 1180 by reading the abstract and then excluded another 73 after full-text reading (Figure 1). The remaining 28 articles were read by all five authors, who agreed on 12 fulfilling the inclusion criteria. We identified two ongoing studies that fulfilled our PICO (NCT01876095 and NCT01932632). The recruitment of patients had not yet started.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of studies included in this systematic review

Study characteristics

The included studies are described in Table 1. We assessed the seven RCTs to be of high 12, moderate 13–15 or low scientific quality 16–18. The five non-RCTs were of moderate 19 or low quality 20–23. Ten of the 12 studies contained a total of 10 861 patients (4669 in RCTs and 6192 in non-RCTs). In the remaining two studies, we could not obtain the exact number of patients 14,19. The mean age of included patients varied between 78 and 86 years, and the patients were treated with an average of 4–12 drugs. The time of follow-up was up to 12 months, with only one study having a follow-up of <6 months 13. In none of the studies did the authors report conflicts of interest regarding medication reviews.

Table 1.

Extracted data from the included studies evaluating medication reviews in nursing home residents

| Results (intervention vs. control group) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors (year) | Country | Study design | Patients (n) | Lost to follow-up (n) | Mortality | Hospitalizations | Comments | Study quality* |

| Cavalieri et al. (1993) [16] | USA | Randomized controlled | I: 33 | – | Mean days alive since admission: 274 vs. 235 | Mean number of hospital admissions: 0.6 vs. 0.6 | I: MR3; geriatric assessment team (geriatrician + geriatric nurse practitioners); responsible physician involved | Low |

| C: 36 | C: standard care | |||||||

| F: 12 months | ||||||||

| PE: not defined. No power calculation | ||||||||

| Crotty et al. (2004) [13] | Australia | Randomized (cluster) controlled | I: 50 | – | Deceased: 18 (36.0%) vs. 27 (26.0%) | NR | I: MR3; multidisciplinary case conferences (GP, geriatrician, pharmacist, residential care staff and representative of the Alzheimer’s Association of South Australia); responsible physician involved | Moderate |

| (5 NHs) | C: standard care | |||||||

| C: 104 | F: 3 months | |||||||

| (10 NHs, 5 of which were the same as above) | PE: MAI. Power calculation available | |||||||

| Furniss et al. (2000) [17] | UK | Randomized (cluster) controlled | I: 158 | – | Deceased: 26 (16.5%) vs. 28 (15.8%) | Mean in-patient days: | I: MR1; medication review by pharmacists; responsible physician not involved | Low |

| (7 NHs) | Intervention period only: 4 vs. 14 deceased, P = 0.028 | NR | C: standard care | |||||

| C: 172 | Observation period only, 1.44 vs. 1.51 | F: 4 month observation + 4 month intervention | ||||||

| (7 NHs) | Intervention period only, 0.55 vs. 1.26 | PE: change in CRBS. Power calculation available | ||||||

| Lapane et al. (2011) [14] | USA | Randomized (cluster) controlled | 2003: | – | Incidence rate per 1000 resident-months, 2003 + 2004: 20.8 vs. 23.1 | Incidence rate per 1000 resident-months, 2003 + 2004: 38.7 vs. 34.2 | I: MR1; medication review by pharmacists with GRAM; responsible physician not involved | Moderate |

| I: 1711 | HR: 0.90 | HR: 1.13 | C: medication review by pharmacists without GRAM | |||||

| (12 NHs) | aHR (95% CI): 0.89 (0.73–1.08) | aHR (95% CI): 1.11 (0.94–1.31) | F: time to event, last date in NH, death or 31 December 2004 | |||||

| C: 1491 | PE: ADE-related hospitalization rate per 100 resident-months. Power calculation available | |||||||

| (13 NHs) | ||||||||

| 2004: | ||||||||

| I: 1769 | ||||||||

| (12 NHs) | ||||||||

| C: 1552 | ||||||||

| (13 NHs) | ||||||||

| Pope et al. (2011) [12] | Ireland | Randomized controlled | I: 110 | – | Deceased: 17 (15.5%) vs. 11 (9.6%) | Number of patients with hospitalizations: 10 (9.1%) vs. 6 (5.2%) | I: MR3; specialist geriatric input. Medical assessment by a geriatrician and medication review by a multidisciplinary expert panel including geriatricians pharmacists and nurses; responsible physician not involved | High |

| C: 115 | P = 0.23 | C: standard care | ||||||

| F: 6 months | ||||||||

| PE: number of drugs and medication cost. No power calculation | ||||||||

| Roberts et al. (2001) [18] | Australia | Randomized (cluster) controlled | I: 905 | I: 83 (+2 missing in the flow chart) | Deceased: 216 (23.9%) vs. 617 (26.5%) | Mean number of hospitalizations (95% CI): Prestudy, 17.67 (11.59–23.75) vs. 22.70 (18.83–26.57) Post-study, 15.86 (10.55–21.16) vs. 18.36 (15.07–21.65) Percentage change, +1.30 (–26.32 to 28.91) vs. −16.86 (–30.62 to 3.11) | I: MR1; 1 year clinical pharmacy programme; responsible physician not involved | Low |

| (13 NHs) | C: 51 (+49 missing in the flow chart) | C: standard care | ||||||

| C: 2325 | F: 12 months (pre- and post-study, respectively) | |||||||

| (39 NHs) | PE: not specified. Power calculations according to RCI and mortality | |||||||

| Zermansky et al. (2006) [15] | UK | Randomized controlled | I: 331 | I: 3 | Deceased: 51 (15.3%) vs. 48 (14.5%) P = 0.81 | Number of patients with hospitalizations: 47 (14.2%) vs. 52 (15.8%) | I: MR3; medication review by pharmacist; responsible physician not involved | Moderate |

| C: 330 | C: 4 | P = 0.62 | C: standard care | |||||

| F: 6 months | ||||||||

| PE: number of changes in medication. Power calculation according to measures of cognitive and physical functioning | ||||||||

| Garfinkel et al. (2007) [20] | Israel | Nonrandomized controlled | I: 119 | – | Deceased: 25 (21%) vs. 32 (45%) | NR | I: MR3; medication review by a physician according to a geriatric–palliative algorithm which resulted in a change in medication; responsible physician involved | Low |

| C: 71 | P < 0.001 | C: medication review by a physician according to a geriatric–palliative algorithm which did not result in a change in medication | ||||||

| F: 12 months | ||||||||

| PE: drug discontiuation. No power calculation | ||||||||

| King & Roberts (2001) [21] | Australia | Nonrandomized controlled | I: 75 | I: 0 | Deceased: 7 (6%) vs. 50 (15%) | NR | I: MR3; multidisciplinary case conference reviews by GPs, GP project officer, pharmacist, nurses and other health professionals; responsible physician involved | Low |

| C: 170 | C: 4 | Percentage figures are adjusted for time in NH | C: standard care | |||||

| P = 0.07 | F: 10.5 months | |||||||

| PE: Medication use and cost, and mortality. No power calculation | ||||||||

| Lapane et al. (2011) [19] | USA | Nonrandomized controlled, pre–post design | I: ≈ 1824 (beds) | – | Incidence rate per 1000 resident-months: Prestudy, 12.1 vs. 17.13 Post-study, 14.4 vs. 17.08 | Incidence rate per 1000 resident-months: Prestudy, 45.4 vs. 35.8 Post-study, 49.8 vs. 44.1 | I: MR1; medication review by pharmacists according to the Fleetwood Model of Long-Term Care Pharmacy; responsible physician not involved | Moderate |

| (12 NHs) | C: medication review by pharmacists | |||||||

| C: ≈ 1638 | F: time to event, last date in NH, death or 31 December 2004 | |||||||

| (beds) | PE: ADE-related hospitalization rate per 100 resident-months. Power calculation available | |||||||

| (13 NHs) | ||||||||

| Olsson et al. (2010) [22] | Sweden | Nonrandomized controlled | I: 135 | – | Deceased: 34 (25.2%) vs. 46 (27.5%) | Percentage of patients with hospitalizations: Study period, 7.4 vs. 14.4% Post-study period, 10.4 vs. 10.9% | I: MR3; patient-focused drug surveillance by physicians; responsible physician involved | Low |

| (4 NHs) | C: standard care | |||||||

| C: 167 | F: 12 months | |||||||

| (4 NHs) | PE: death or hospitalization. Power calculation available | |||||||

| Trygstad et al. (2009) [23] | USA | Nonrandomized controlled | n = 5255 | – | NR | In one out of 10 cohorts (retrospective medication review), a reduction in hospitalizations was reported RR: 0.84 (95% CI: 0.71–1.00) P = 0.04 | I: MR1; medication reviews with MTMP; responsible physician not involved | Low |

| (253 NHs) | C: medication reviews | |||||||

| F: 9 months | ||||||||

| PE: drug costs. No power calculation | ||||||||

Abbreviations are as follows: ADE, adverse drug event; aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; C, control; CI, confidence interval; CRBS, Crichton Royal Behaviour Rating Scale; F, follow-up; GP, general practitioner; GRAM, Geriatric Risk Assessment MedGuide; HR, hazard ratio; I, intervention; ITT, intention to treat; MAI, Medication Appropriateness Index; MR1, medication review type 1 4; MR3, medication review type 3 4; MTMP, Medication Therapy Management Program; NH, nursing home; NR, not reported; PE, primary end-point; RCI, Resident Classification Instrument); RR, relative risk.

According to modified instructions by the Swedish Council on Health Technology Assessment.

Eight studies compared medication reviews with standard care. The intervention was performed by a multiprofessional team that included pharmacists 12,13,21, pharmacists only 15,17,18, physicians only 22 or geriatricians and geriatric nurses 16. The other four studies investigated either information technology 14 or educational 19 support for medication reviews, or compared patient groups selected on the basis of the results of the medication review 20,23.

Mortality

Seven RCTs and four non-RCTs reported data on mortality. None had the power to detect differences in mortality, although one non-RCT stated mortality as the primary end-point 22.

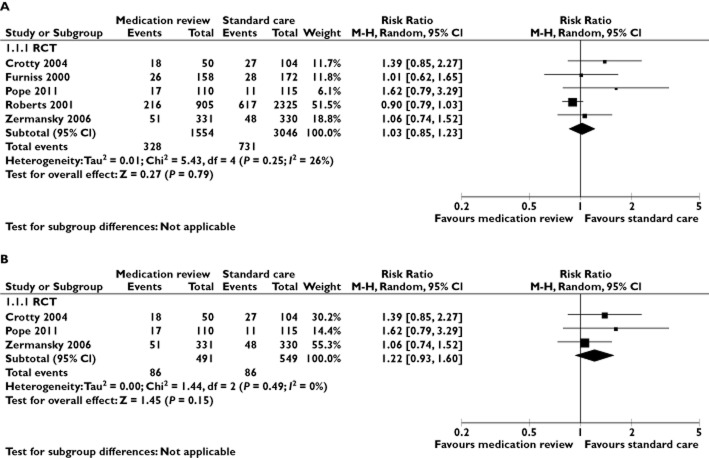

Five RCTs compared medication reviews with standard care and reported the number of deceased patients in the intervention and the control group 12,13,15,17,18. These were pooled in a meta-analysis (Figure 2A). The risk ratio for all-cause mortality was 1.03 for intervention vs. control patients (95% CI 0.85–1.23; I2 = 26%). In the sensitivity meta-analysis that included only studies of high or moderate quality (Figure 2B) 12,13,15, the corresponding risk ratio was 1.22 (95% CI 0.93–1.60; I2 = 0%).

Figure 2.

A meta-analysis of RCTs in nursing home residents comparing the effect of medication reviews with standard care on mortality (A) and in the subgroup of these trials with moderate or high quality (B). CI, confidence interval; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel; RCT, randomized controlled trial

The two RCTs that were not included in the meta-analysis did not observe any statistically significant differences in outcomes related to mortality 14,16. No additional data were obtained.

Two non-RCTs compared medication reviews with standard care. Neither of them reported a statistically significant difference in mortality between the study groups 21,22. Two non-RCTs compared two different kinds of medication reviews. One of them reported significantly fewer deaths in the group of patients in which the medication review had resulted in a change in the medication list in comparison to the group of patients in which no change was made 20. The other reported no statistically significant difference between the study groups 19.

Hospitalizations

Six RCTs and three non-RCTs reported data on hospitalizations. None of them had the power to detect differences in hospitalization, although one non-RCT stated hospitalization as primary end-point 22.

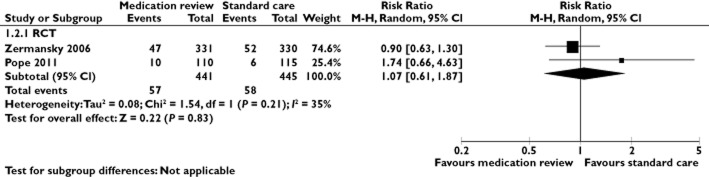

Two RCTs compared medication reviews with standard care and reported the number of hospitalized patients in the intervention and the control group 12,15. These were pooled in a meta-analysis (Figure 3). The risk ratio for hospitalization was 1.07 for intervention vs. control patients (95% CI 0.61–1.87; I2 = 35%).

Figure 3.

A meta-analysis of RCTs in nursing home residents comparing the effect of medication reviews with standard care on hospitalization. CI, confidence interval; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel; RCT, randomized controlled trial

None of the four RCTs that were not included in the meta-analyses reported any statistically significant differences in hospitalization variables between the study groups 14,16–18. We received additional data from one study; there were 87 and 283 hospitalized individuals in the intervention and the control group, respectively 18. In that study, baseline hospitalization rates varied considerably between the randomization groups.

One non-RCT compared medication reviews with standard care. No statistically significant difference was observed between the study groups 22. The remaining two non-RCTs compared different types of medication reviews. In neither of them were relevant differences observed in the rate of hospitalizations 19,23.

Discussion

Main study findings

The main finding of this systematic review and meta-analysis is that medication reviews, performed by pharmacists or multiprofessional teams, for older people who live in nursing homes do not seem to have beneficial effects on mortality or hospitalization. This has important implications, because such reviews have been proposed, and have sometimes even already been introduced, as a method to solve the problem of inappropriate drug treatment in the elderly.

Strengths

The most important strength of the present review is the focus on mortality and hospitalization. The importance of these outcomes for the individual patient and the healthcare system is unquestionable. Other outcome variables, which focus only on potentially harmful effects of drug treatment, may be suboptimal because they represent only one side of the coin. Such effects must be weighed against the potential benefits of pharmacotherapy. Thus, all-cause mortality and hospitalization may represent the overall net effect of any intervention aiming to improve the health of the patients. Moreover, there is a great deal of uncertainty in the judgement of whether a case of death or a hospitalization is primarily drug related or not. Such assessments always include subjective input.

Another strength of this review is the focus on nursing home residents. The need to optimize drug treatment in this category of patients is well known, and medication reviews have been shown to be the most common component to optimize prescribing in this setting 9. Furthermore, the inclusion of non-RCTs in addition to RCTs gives a comprehensive overview of available scientific evidence.

The strict adherence to established HTA routines and the number of individual assessors are further advantages of the review. This approach may be particularly important in the research field of medication reviews, because the field implies potential conflicts of interest. Indeed, a prerequisite for medication reviews is allocation of resources. As this intervention is predominantly performed by pharmacists, and resources are limited, the implementation of medication reviews in clinical practice implicates that resources are reallocated from other healthcare professionals and/or activities. Therefore, conflicts of interests related to funding and contributions by professions are likely.

Limitations

The main limitation is that there were few published studies of sufficient scientific quality that adequately addressed the effects of medication reviews in this particular patient category. Another limitation is that none of the included studies had the power to detect superiority with regard to mortality or hospitalization, nor were they designed to detect non-inferiority. Indeed, only 886 patients could be included in the meta-analysis of hospitalization, which resulted in rather low precision, with a wide confidence interval of the pooled estimate.

Another important limitation is the various settings of the studies. The routines of drug treatment and prescribing differ between countries. Therefore, the content of standard care may vary. Furthermore, the level of care may differ between nursing homes. In addition, the heterogeneity of the intervention needs to be considered. However, all studies included in the meta-analyses involved a third party that was not directly responsible for the patient. This person or team routinely assessed the drug treatment and, when applicable, recommended changes.

Relationship to other studies

The results of this systematic review show that the conclusion of the meta-analysis published in 2008, i.e. that medication reviews do not have any beneficial effects on mortality and hospitalization 7, is valid also in the nursing home setting. Furthermore, the results are in agreement with the recently published Cochrane reviews on medication reviews in hospitalized patients 8 and interventions for optimized prescribing in older people in care homes 9.

Our meta-analyses do not exclude a beneficial effect of medication reviews. Although all point estimates favoured standard care, the confidence intervals crossed the line of unity and were rather wide. However, the sensitivity analysis regarding all-cause mortality indicates that it is unlikely that the addition of future studies would result in a pooled effect that would favour medication reviews. Indeed, inclusion of low-quality studies in a meta-analysis can be questioned because such studies may bias the results 11.

It may be argued that quality of life could be a relevant end-point. However, a recent Cochrane review found no studies that measured this end-point within the field of optimizing prescribing in care homes 9. Furthermore, such an end-point may include interpretation difficulties. Indeed, when you add extra time and effort to a patient, regardless of the focus area, quality of life may be affected. Thus, to take this potential ‘placebo effect’ into consideration, a double-blind design would be preferable. This may be hard to achieve within the field of medication reviews and, as far as we are aware, such studies are lacking. Indeed, a Cochrane review reported that no studies were found concerning pharmacist services vs. services delivered by other health professionals 24.

A previous review 25 reported that MAI or Beers criteria were often used as outcome measures in pharmacist interventions for improved prescribing practices. Indeed, such criteria have been the primary outcomes in a Cochrane review on interventions for improved use of polypharmacy in older people 26. The present review confirms the focus on surrogate outcomes within this research area, as illustrated by the primary end-points number of drugs 12,21, drug costs 12,21,23, number of medication changes 15 and drug discontinuations 20. It is important to point out that such surrogate outcomes, in contrast to patient-relevant outcomes, yield effect estimates that are more favourable for the intervention 27. Furthermore, the relationship between these surrogate outcomes and mortality or hospitalization has not yet been clarified.

There are several potential explanations for our findings. First, selection bias cannot be excluded, especially as most studies were of low or moderate scientific quality. One may also speculate that frail older patients may have a reduced compensatory capacity for the physiological alterations that may occur upon drug treatment changes.

Another possible explanation of our findings may be that medication review often implies that more persons than the responsible physician are involved in the pharmaceutical care of the patient. This kind of teamwork has been perceived not only to prevent, but also to cause prescribing errors, as the responsible physician may rely on another person to identify errors made 28. Furthermore, in order to weigh risks and benefits for treatment alternatives in a specific patient it is sometimes necessary to deviate from general guidelines. The prescribing physician, who has the overall medical responsibility for the care of the patient, is probably the person best suited for such decisions.

A third explanation is that patients and their caretakers who receive conflicting information from different sources regarding the drug treatment may be confused. The responsible physician and the professionals responsible for the medication review may have different opinions on the most appropriate treatment. Indeed, this assumption is supported by the recently reported mean implementation rate of 50% of recommendations 29. One may speculate that conflicting information may reduce patient adherence and, consequently, affect patient outcome.

Although economic evaluations of clinical pharmacy services suffer from methodological limitations 30 and solid evidence with regard to head-to-head comparisons of standard care with interventions that require additional resources are still lacking 24, the studies in the present review indicate that great resources are currently being spent on medication reviews. It may be argued that this intervention reduces costs of drugs and therefore pays for itself. In the review by Holland et al., medication reviews resulted in a statistically significant small reduction in the number of drugs 7. Therefore, it is not surprising that the costs for drugs could be reduced. However, the medication review in itself also requires resources. In two of the studies included in the present systematic review, the savings in drug costs were related to the amount of resources spent on the intervention. In one study, a net cost was reported 12, whereas the other reported a net saving 18. In this context, it is important to emphasize that undertreatment, as well as overtreatment, are both prevailing problems 1. Indeed, when evaluating economical aspects of medication reviews, the benefits of drug treatment also need to be taken into account, preferably by the generic measure of incremental costs per quality-adjusted life year. However, to the best of our knowledge, only two cost–utility analyses of medication reviews in the setting of RCTs have been published. They addressed home-based and in-patient medication reviews, respectively 31,32. Both studies reported that the costs per quality-adjusted life year were higher than normally accepted by the society and, thus, the intervention was probably not cost-effective 33,34.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that medication reviews do not reduce mortality and hospitalization in nursing home residents. The results may be valuable for decision-makers and for researchers designing future studies. Much research remains to be done in order to clarify how drug treatment can be optimized in older people in this setting.

Competing Interests

All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organization for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

The authors are grateful to the research librarians Ann Liljegren and Yommine Holmberg-Hjalmarsson, who performed the literature search and the initial exclusion of studies according to the inclusion criteria.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s website:

Search strategies

References

- Gallagher PF, O’Connor MN, O’Mahony D. Prevention of potentially inappropriate prescribing for elderly patients: a randomized controlled trial using STOPP/START criteria. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89:845–854. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leendertse AJ, Visser D, Egberts AC, van den Bemt PM. The relationship between study characteristics and the prevalence of medication-related hospitalizations: a literature review and novel analysis. Drug Saf. 2010;33:233–244. doi: 10.2165/11319030-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wester K, Jonsson AK, Spigset O, Druid H, Hagg S. Incidence of fatal adverse drug reactions: a population based study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;65:573–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.03064.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clyne W, Blenkinsopp A, Seal R. 2008. A guide to medication review. Accessed at http://www.npc.nhs.uk/review_medicines/intro/resources/agtmr_web1.pdf (last accessed 12 March 2014)

- Samsa GP, Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, Weinberger M, Clipp EC, Uttech KM, Lewis IK, Landsman PB, Cohen HJ. A summated score for the medication appropriateness index: development and assessment of clinimetric properties including content validity. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:891–896. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90192-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Geriatrics Society. Updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:616–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland R, Desborough J, Goodyer L, Hall S, Wright D, Loke YK. Does pharmacist-led medication review help to reduce hospital admissions and deaths in older people? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;65:303–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.03071.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen M, Lundh A. Medication review in hospitalised patients to reduce morbidity and mortality. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008986.pub3. CD008986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alldred DP, Raynor DK, Hughes C, Barber N, Chen TF, Spoor P. Interventions to optimise prescribing for older people in care homes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009095.pub2. CD009095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regional Health Technology Assessment Centre. 2012. [Granskningsmall för randomiserad kontrollerad prövning, Granskningsmall för kohortstudier med kontrollgrupper]. Accessed at http://www.sahlgrenska.se/sv/SU/Forskning/HTA-centrum/Hogerkolumn-undersidor/Hjalpmedel-under-projektet/ (last accessed 12 March 2014)

- Hartling L, Ospina M, Liang Y, Dryden DM, Hooton N, Krebs Seida J, Klassen TP. Risk of bias versus quality assessment of randomised controlled trials: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2009;339:b4012. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope G, Wall N, Peters CM, O’Connor M, Saunders J, O’Sullivan C, Donnelly TM, Walsh T, Jackson S, Lyons D, Clinch D. Specialist medication review does not benefit short-term outcomes and net costs in continuing-care patients. Age Ageing. 2011;40:307–312. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crotty M, Halbert J, Rowett D, Giles L, Birks R, Williams H, Whitehead C. An outreach geriatric medication advisory service in residential aged care: a randomised controlled trial of case conferencing. Age Ageing. 2004;33:612–617. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afh213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapane KL, Hughes CM, Daiello LA, Cameron KA, Feinberg J. Effect of a pharmacist-led multicomponent intervention focusing on the medication monitoring phase to prevent potential adverse drug events in nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1238–1245. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03418.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zermansky AG, Alldred DP, Petty DR, Raynor DK, Freemantle N, Eastaugh J, Bowie P. Clinical medication review by a pharmacist of elderly people living in care homes–randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2006;35:586–591. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalieri TA, Chopra A, Gray-Miceli D, Shreve S, Waxman H, Forman LJ. Geriatric assessment teams in nursing homes: do they work? J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1993;93:1269–1272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furniss L, Burns A, Craig SK, Scobie S, Cooke J, Faragher B. Effects of a pharmacist’s medication review in nursing homes. Randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:563–567. doi: 10.1192/bjp.176.6.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts MS, Stokes JA, King MA, Lynne TA, Purdie DM, Glasziou PP, Wilson DA, McCarthy ST, Brooks GE, de Looze FJ, Del Mar CB. Outcomes of a randomized controlled trial of a clinical pharmacy intervention in 52 nursing homes. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;51:257–265. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2001.00347.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapane KL, Hughes CM, Christian JB, Daiello LA, Cameron KA, Feinberg J. Evaluation of the fleetwood model of long-term care pharmacy. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12:355–363. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel D, Zur-Gil S, Ben-Israel J. The war against polypharmacy: a new cost-effective geriatric-palliative approach for improving drug therapy in disabled elderly people. Isr Med Assoc J. 2007;9:430–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King MA, Roberts MS. Multidisciplinary case conference reviews: improving outcomes for nursing home residents, carers and health professionals. Pharm World Sci. 2001;23:41–45. doi: 10.1023/a:1011215008000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson IN, Curman B, Engfeldt P. Patient focused drug surveillance of elderly patients in nursing homes. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19:150–157. doi: 10.1002/pds.1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trygstad TK, Christensen DB, Wegner SE, Sullivan R, Garmise JM. Analysis of the North Carolina long-term care polypharmacy initiative: a multiple-cohort approach using propensity-score matching for both evaluation and targeting. Clin Ther. 2009;31:2018–2037. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nkansah N, Mostovetsky O, Yu C, Chheng T, Beney J, Bond CM, Bero L. Effect of outpatient pharmacists’ non-dispensing roles on patient outcomes and prescribing patterns. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(7) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000336.pub2. CD000336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur S, Mitchell G, Vitetta L, Roberts MS. Interventions that can reduce inappropriate prescribing in the elderly: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2009;26:1013–1028. doi: 10.2165/11318890-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson SM, Hughes C, Kerse N, Cardwell CR, Bradley MC. Interventions to improve the appropriate use of polypharmacy for older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(5) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008165.pub2. CD008165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciani O, Buyse M, Garside R, Pavey T, Stein K, Sterne JA, Taylor RS. Comparison of treatment effect sizes associated with surrogate and final patient relevant outcomes in randomised controlled trials: meta-epidemiological study. BMJ. 2013;346:f457. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross S, Ryan C, Duncan EM, Francis JJ, Johnston M, Ker JS, Lee AJ, Macleod MJ, Maxwell S, McKay G, McLay J, Webb DJ, Bond C. Perceived causes of prescribing errors by junior doctors in hospital inpatients: a study from the protect programme. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22:97–102. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwint HF, Bermingham L, Faber A, Gussekloo J, Bouvy ML. The relationship between the extent of collaboration of general practitioners and pharmacists and the implementation of recommendations arising from medication review: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2013;30:91–102. doi: 10.1007/s40266-012-0048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Rijdt T, Willems L, Simoens S. Economic effects of clinical pharmacy interventions: a literature review. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65:1161–1172. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland R, Lenaghan E, Harvey I, Smith R, Shepstone L, Lipp A, Christou M, Evans D, Hand C. Does home based medication review keep older people out of hospital? The HOMER randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2005;330:293. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38338.674583.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bladh L, Ottosson E, Karlsson J, Klintberg L, Wallerstedt SM. Effects of a clinical pharmacist service on health-related quality of life and prescribing of drugs: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20:738–746. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2009.039693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacini M, Smith RD, Wilson EC, Holland R. Home-based medication review in older people: is it cost effective? Pharmacoeconomics. 2007;25:171–180. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200725020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstedt SM, Bladh L, Ramsberg J. A cost-effectiveness analysis of an in-hospital clinical pharmacist service. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e000329. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Search strategies