Abstract

Context

Individuals with diabetes are at greatly increased risk for developing cardiovascular disease (CVD), but more aggressive targets for risk factor control have not been tested.

Objective

To compare the progression of subclinical atherosclerotic disease in diabetic adults treated to aggressive targets of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) ≤ 70 mg/dL and blood pressure (BP) ≤ 115/75 mm Hg (aggressive) versus treatment to standard targets of LDL-C ≤ 100 mg/dL and BP ≤ 130/85 mm Hg (standard).

Design

Randomized, open label, blinded-to-endpoint 3-year trial in individuals with diabetes conducted April 2003-July 2004.

Setting

Four clinical centers in southwestern Oklahoma; Phoenix, AZ; northeastern Arizona; and South Dakota.

Participants

499 American Indian men and women ≥ age 40 with type 2 diabetes and no prior CVD events.

Interventions

Participants were randomized to aggressive vs. standard treatment. The same treatment algorithms were followed for both groups.

Main Outcome Measures

Primary endpoint was a composite of progression of atherosclerosis as measured by common carotid artery intimal medial thickness (IMT) and clinical events. Secondary endpoints included other carotid and cardiac ultrasonographic measures.

Results

LDL-C and systolic BP (SBP) goals for both groups were reached within 12 months and maintained to 36 months. LDL-C and SBP in the last 12 months averaged 72 and 104 mg/dL and 116 and 129 mm Hg in the aggressive and standard groups, respectively. Regression of IMT (-0.017 vs. 0.041 mm, p < .0001) and arterial mass (-0.14 vs. 1.14 mm2, p < .0001) and greater decrease in left ventricular mass (-2.4 vs. -1.3 g/m2.7, p = .05) were observed in the aggressive group. Clinical CVD events were lower than expected and did not differ between groups

Conclusions

Reducing LDL-C and SBP to lower targets resulted in regression of carotid IMT and greater decrease in left ventricular mass in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Clinical events were lower than expected and did not differ significantly between groups. Further follow-up is needed to determine whether these improvements will result in lower long-term CVD event rates and costs and favorable risk-benefit outomes.

Individuals with diabetes are at increased risk for developing cardiovascular disease (CVD), and coronary heart disease (CHD) is the leading cause of death in diabetic adults.1 2 3 The increased diabetes-associated CVD risk is due in large part to the higher prevalence of other major CVD risk factors, such as dyslipidemia and hypertension, in diabetic individuals.4 5 Prevention of CVD and control of CVD risk factors in diabetic individuals has become a priority. Expert panels have defined targets for low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C)6 and blood pressure (BP)7 in diabetic patients based on epidemiological and clinical trial data. However, a number of secondary prevention studies in high-risk patients have suggested that LDL-C lowering beneath the current target may be associated with improved outcomes in diabetic individuals.8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Several studies using statin therapy in high-risk diabetic patients also have suggested that further reduction in CVD events may be achieved in individuals who are at or below current LDL-C targets. 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 In addition, antihypertensive treatment to levels below recommended goals may delay progression of microalbuminuria to clinical proteinuria in diabetes.26 Because no studies have specifically evaluated the benefits and risks of aggressive treatment targets for both LDL-C and BP in diabetic individuals, the optimal treatment targets remain elusive.

A large body of epidemiologic data in American Indians, a population with high prevalence of diabetes and diabetes-related CVD, documents strong relations between LDL-C and BP levels and CVD events.27 28 These data suggest that lowering LDL-C and BP beyond current targets could help retard or reverse CVD in diabetic patients. Thus, the present study was undertaken to compare progression of subclinical atherosclerotic disease, as evaluated by carotid ultrasound, in diabetic American Indians ages ≥ 40 years, randomly assigned to either aggressive targets of LDL-C ≤ 70 mg/dL plus BP ≤ 115/75 mm Hg or current standard targets of LDL-C ≤ 100 mg/dL and BP ≤ 130/85 mm Hg. Impact on cardiac structure and function was also evaluated.

METHODS

Details of this study design and methods have been published.29 30 All participants provided written informed consent, and the study was approved by all participating institutional review boards (IRBs), the National Institutes of Health, and all participating American Indian communities.

Recruitment

Briefly, 548 diabetic men and women ≥ age 40 were enrolled between May 2003 and July 2004 at four clinical centers in the United States: southwestern Oklahoma; Phoenix, AZ; northeastern Arizona; and South Dakota. Participants were randomly assigned to the aggressive (n = 276) or standard treatment group (n = 272), stratified by center and gender. All participants were American Indians as defined by Indian Health Service (IHS) criteria.31 Eligibility criteria included documented type 2 diabetes,32 33 plus LDL-C ≥ 100 mg/dL and systolic BP (SBP) > 130 mm Hg within the previous 12 months. Major exclusion criteria included Class III or IV heart failure, SBP > 180 mm Hg, liver transaminase levels > twice the upper limit of normal, or diagnosis of primary hyperlipidemia or hypercholesterolemia due to hyperthyroidism or nephrotic syndrome.

Lipid and BP Interventions

Study personnel performed BP and lipid management for both groups, with equal frequency of clinic visits. All other medical care, including diabetes management, was performed by the participants’ IHS health care providers.

The algorithm for hypertension management was based on the Sixth Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC VI).7 The goals of therapy were SBP ≤ 115 mm Hg and ≤ 130 mm Hg in the aggressive and standard groups, respectively. Secondary goals were diastolic BP (DBP) of ≤ 75 and ≤ 85 mm Hg, respectively. Step 1 drugs were angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) in the case of intolerance to ACE inhibitors. Step 2 was hydrochlorothiazide. Steps 3-5 added calcium channel blockers, beta-blockers, and then alpha-blockers and other vasodilators.

The algorithm for achieving lipid goals was based on recommendations of the National Cholesterol Education Program - Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP-ATP III). 6 34 LDL-C goals were ≤ 70 and ≤ 100 mg/dL and non high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (non-HDL-C) goals were ≤ 100 and ≤ 130 mg/dL in the aggressive and standard groups, respectively. If lifestyle modification was unsuccessful, a statin was initiated. If the LDL-C goal was not reached with a statin, combination therapy with ezetimibe was used. In addition, the non-HDL-C goals were addressed using fish oil, fenofibrate, or niacin. Details of the intervention procedures and targets have been published.29

Baseline and Follow-up Visits

All procedures followed standardized methods performed by trained, certified personnel. The baseline visit included a physical exam, electrocardiogram, carotid artery ultrasound, echocardiogram, and collection of demographic data, health history, and current medication use. Height, weight, waist circumference, and seated BP were measured, and fasting blood samples were collected to measure chemistry panel, lipoprotein profile, glucose, hemoglobin A1c, C-reactive protein (CRP), and creatinine, and urine samples for urinary albumin and creatinine.29

Participants were followed from date of entry until death, loss-to-follow up, request for no further contact, or completion of the study, regardless of adherence to the medication intervention. At follow-up visits after 1 month, and then every 3 months until 36 months, seated and standing BP (with orthostatic hypotension defined as a SBP fall of > 20 mm Hg after 2 minutes of standing and with symptoms lasting longer than 1 minute) and a lipid profile (using a Cholestech apparatus [Cholestech Corporation, Hayward, CA] standardized against the laboratory assay)35 were measured. Medications were adjusted to meet treatment goals, side effects were assessed, and information on health outcomes was obtained. Fasting blood and urine samples were obtained at 36 months to repeat all baseline measurements; additionally, fasting blood samples for complete lipoprotein profile and urine samples for albumin and creatinine were obtained at 6, 12, 24, and 30 months.

Outcomes Ascertainment

At the baseline, 18-, and 36-month visits, carotid and cardiac ultrasound studies were performed following standardized protocols36 by centrally trained sonographers and interpreted at a core reading center by physician readers blinded to treatment assignment. For carotid ultrasound studies, B-mode imaging from multiple angles was performed to determine the presence and location of plaque (focal protrusion of the vessel ≥ 50% greater than the surrounding wall), as well as arterial wall dimensions. Plaque score (0-8) was determined as the number of segments of each artery containing plaque. End-diastolic B-mode images of the distal right and left common carotid artery were acquired in real-time, and a 1-cm segment of the far wall was measured using an automated system employing an edge detection algorithm with manual override capacity. One hundred separate dimensional measurements were obtained from the 1-cm segment and averaged to obtain mean intimal medial thickness (IMT) and lumen diameter. Arterial mass (cross-sectional area) was calculated using end-diastolic IMT and diameter measurements.37

Echocardiographic measures included assessment of left ventricular (LV) structure and function.38 39 Methods for ascertaining and classifying clinical outcomes have been described.29 Medical records for all hospitalizations and outpatient coronary revascularization procedures were reviewed centrally by a panel of six physician adjudicators blinded to treatment assignment. The primary CVD endpoint included fatal and non-fatal CVD events, defined as fatal CHD or stroke, nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI) or stroke, unstable angina, cardiac revascularization, and carotid arterial revascularization.

Data Analysis

The primary endpoint (identified at the beginning of the trial) was defined as a composite outcome of change from baseline to 36 months in common carotid artery (CCA) IMT and/or a primary CVD event. The primary hypothesis was that, compared with standard ATP III and JNC VI goals, achieving lower targets for LDL-C and BP will retard progression of atherosclerosis, as measured by change in carotid IMT and CVD events. Changes in carotid and ECHO measures were defined as secondary endpoints. The treatment effects on IMT at 18 or 36 months testing the primary hypothesis were compared in an intent-to-treat analysis using the worst-rank score method of Wei and Lachin40 for differences in IMT from baseline to 36 months after adjustment for baseline IMT and center. Participants who had a primary CVD event prior to 18 or 36 months were assigned a worse rank score than those with the greatest increase in IMT. Fatal events were ranked worse than non-fatal ones, and earlier events had worse ranks. The 36-month IMT measures of participants who died from non-CV causes or were lost to follow-up prior to 18 months were considered missing at random, and these participants (n = 10) were excluded from the analysis. For those who had 18- but not 36-month values (n = 18 for carotid measures and 47 for ECHO measures) and no primary event, the 18-month value was used in the 36-month analyses.

Because few CVD events occurred, standard parametric procedures were also used. Mean changes in the aggressive vs. standard groups for carotid and echocardiographic parameters and differences between changes in the two groups were evaluated with log-transformation as needed. Predefined secondary endpoints included CCA mass, plaque score, LV geometry and function, and CRP; safety measures were also examined.

Additional intention-to-treat analyses compared changes in IMT and LV mass index (LVMI) between the treatment groups stratified by predefined baseline characteristics, including age, gender, obesity, SBP, LDL-C, non-HDL-C, CRP, and hemoglobin A1c. Comparisons of means for each stratum across treatment groups, and tests for interactions between baseline characteristics and treatment were conducted. In addition, secondary analyses of factors influencing changes in endpoints were evaluated using change in IMT or LVMI as dependent variables in ordinary least squares regression models. Time of treatment effect was explored using models that included number of months at LDL-C or SBP target. A sensitivity analysis was performed to compare those in the aggressive group who maintained either the LDL-C goal of ≤ 70 mg/dL or the SBP goal of ≤ 115 mm Hg during the last 6 months of follow up with those in the standard group. Finally, ordered logit analyses compared the influence of LDL-C and SBP changes on categorical changes in IMT and LVMI variables; in these models the effect of changes in LDL-C and SBP on the probability of observing no change (defined as no change within the variance of the measurement), a decrease, or an increase was tested in models that also controlled for baseline characteristics (i.e., age, body mass index [BMI], gender, and center).

RESULTS

Recruitment and Baseline Characteristics

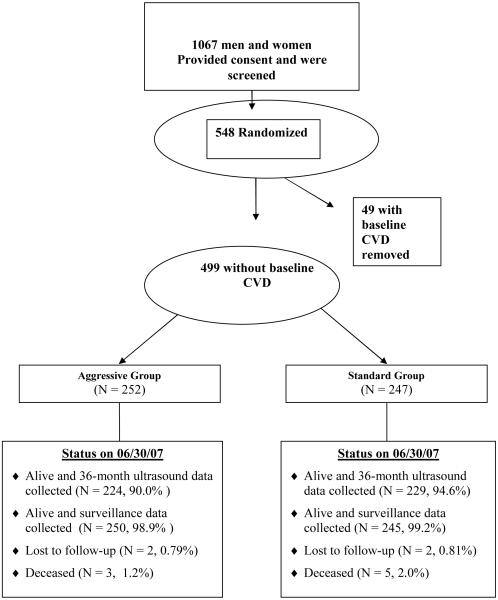

Between April 2003 and July 2004, 548 diabetic men and women ≥ age 40 were randomized (Figure 1). Four months after initiation of recruitment, the Steering Committee voted (with concurrence of the Data and Safety Monitoring Board) to change the LDL-C goal to ≤ 70 mg/dL for those with baseline CVD (n = 49) who had been already randomized into the study to comply with the newly released ATP III recommendations.34 Recruitment was limited thereafter to persons who had not had a prior CVD event, and recruitment continued until the pre-specified sample size was reached. Thus, 499 participants without baseline CVD were included in the analyses (Figure 1). After 36 months, physical examination and blood measurements were obtained on 99%, and carotid ultrasound data were collected on 92% of those alive. Only 4 were lost to follow-up, and CVD endpoints were ascertained in 99%.

Figure 1. Participant Flow in SANDS.

Baseline characteristics of the participants have been described previously (Table 1).30 Mean age was 56 years, 66% were women, average BMI was 33, and 21% were current smokers. At entry, 38% of participants were taking lipid-lowering medication, and 73% were on antihypertensive therapy. Baseline LDL-C averaged 104 mg/dL and systolic BP averaged 131 mm Hg. The majority was on some form of hypoglycemic therapy; hemoglobin A1c averaged 8.1%, and mean duration of diabetes was 8.7 years in the standard group and 9.2 years in the aggressive group.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the SANDS Participants (N = 499)

| Aggressive (N = 252) | Standard (N = 247) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Age (years) | 55.3 (9.3) | 56.9 (8.9) | .05 |

| Gender, women N, %) | 167 (66) | 160 (65) | .73 |

| Body mass index (BMI), kg/m2 | 33.5 (6.6) | 33.2 (6.2) | .57 |

| Waist (cm) | 110.2 (15.4) | 110.1 (14.0) | .90 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | |||

| Total | 184 (33) | 185 (33) | .56 |

| LDL | 104 (30) | 104 (29) | .95 |

| HDL | 46 (13) | 46 (12) | .90 |

| Non-HDL | 138 (32) | 140 (32) | .50 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL)** | 158 (149-167) | 168 (159-177) | .10* |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 128 (15) | 133 (17) | .002 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 74 (10) | 76 (10) | .04 |

| A1c | 8.2 (1.8) | 7.9 (1.8) | .10 |

| Diabetes Therapy | |||

| Lifestyle | 27 (11.0) | 34 (13.9) | .33 |

| Oral hypoglycemics | 206 (82 ) | 180 (73) | .02 |

| Insulin | 70 (28.6) | 53 (22.0) | .10 |

| Insulin plus oral | 247 (98) | 227 (92) | .002 |

| eGFR | 91 (24) | 88 (23) | .21 |

| Smoking | 243 | 244 | |

| Never | 109 (45) | 123 (51) | .20 |

| Current | 54 (22) | 48 (20) | .58 |

| Former | 80 (33) | 73 (30) | .60 |

| Aspirin use (≥ 80 mg) | |||

| Yes | 177 (70) | 168 (69) | .74 |

| CRP (mg/dL)** | 2.7 (2.3-3.1) | 2.8 (2.4-3.3) | .56* |

| Carotid | |||

| IMT (mm) | .810 (.19) | .797 (.17) | .48* |

| Arterial area (mm2) | 17.4 (5.0) | 17.3 (4.6) | .85 |

| Plaque score (1-8) | 1.85 (1.6) | 1.83 (1.7) | .89* |

| Plaque (N, %) | 188 (75) | 188 (76) | .64 |

| Cardiac | |||

| LV mass | 156.7 (38.3) | 156.1 (38.3) | .56* |

| LV mass index (g/m2.7) | 41.2 (9.5) | 40.6 (8.5) | .87* |

| LV ejection fraction | 60.5 (5.7) | 59.8 (5.8) | .26* |

Abbreviations: eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; IMT = intimal medial thickness; LV = left ventricular.

Two-sample comparison t-tests were calculated based on log-transformed variables.

Geometric mean with 95% confidence interval in parenthesis.

The two treatment groups were well matched, with no meaningful differences in baseline characteristics, except that average clinic SBP was 5 mm Hg lower in the group randomized to aggressive therapy. No significant differences were observed in any carotid ultrasound or echocardiographic parameter.

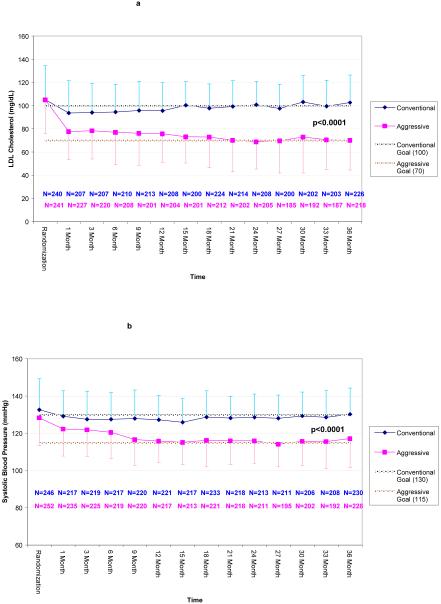

Intervention

On average, the aggressive group achieved the LDL-C goal of ≤ 70 mg/dL within 12 months of randomization, maintaining it consistently throughout 36 months of follow-up. They reached the SBP goal of ≤ 115 mm Hg after 9 months of therapy, also maintaining that goal throughout follow up (Figure 2). Comparable decreases were observed in non-HDL-C, and DBP averaged < 70 mm Hg in the aggressive group (Table 2) throughout the study. LDL-C and BP goals were also maintained in the standard treatment group, with LDL-C at 100 mg/dL during follow up and SBP at 130 mm Hg (Figure 2). During the last 12 months, the difference in LDL-C between the groups was 32 mg/dL and that in SBP was 13 mm Hg (Table 2). Mean weight, average BMI, waist circumference, and fasting glucose also remained unchanged in both groups, but CRP tended to decrease in the aggressive group (p = 0.12 for difference between group changes) at 36 months (Table 2).

Figure 2. Panel A. Mean (SD) LDL cholesterol by treatment group (vertical axis) at 3-month intervals (horizontal axis) throughout the study. Panel B. Mean (SD) systolic blood pressure (vertical axis) by treatment group at 3-month intervals throughout the study.

Note. LDL values were obtained from capillary blood using Cholestech apparatus. For 2292 samples having both laboratory and Cholestech measures, the means (SD) were 89.2 (31.2) and 87.9 (29.1) mg/dL, respectively

Table 2.

Differences in Mean Changes from Baseline to 36 Months, Aggressive vs. Standard Group

| Baseline | 36 months | Mean Change at 36 months | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggressive | Standard | Aggressive | Standard | Aggressive | Standard | Difference | ||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Weight, kg | 90 (20) | 90 (19) | 91 (21) | 91 (21) | 1 (12) | 1 (10) | .22 (-1.8-2.2) | .83 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 33.5 (6.6) | 33.2 (6.2) | 33.8 (6.9) | 33.6 (7.0) | .3 (4.5) | .4 (3.8) | .11 (-.6-.9) | .77 |

| Waist, cm | 110 (15) | 110 (14) | 110 (16) | 110 (15) | .2 (11) | .6 (10) | .4 (-1.5-2.3) | .66 |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 128 (15) | 133 (17) | 116.5 (11) | 129 (10) | -11 (15) | -3 (15) | 8 (5.5-12) | .000 |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 74 (10) | 76 (10) | 67 (8) | 73 (8) | -7 (8) | -3 (9) | 4 (2.5-5.5) | .000 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 184 (33) | 185 (33) | 150 (29) | 187 (27) | -32(39) | 3 (36) | 35(28-42) | .000 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 104 (30) | 104 (29) | 72 (24) | 104 (20) | -31(35) | 1(32) | 32(26-38) | .000 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 46 (13) | 46 (12) | 48 (13) | 48 (13) | 3(9) | 3(11) | .1(-1.9-1.8) | .94 |

| Total cholesterol/HDL-C | 4.2 (1.1) | 4.2 (1.1) | 3.3 (1.0) | 4.0 (1.0) | -1(1.0) | -.1(1.1) | .8(.6-1) | .000 |

| Non-HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 138 (32) | 140 (32) | 102 (29) | 138 (26) | -35 (38) | .2(36) | 35(28-42) | .000 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL (geo mean and 95% CI) | 158(149-167) | 168 (159-177) | 137(130-144) | 160 (153-168) | -26(78)* | -12(84)* | 14(-2.8-29)* | .06* |

| CRP mg/dL (geo mean and 95% CI) | 2.7 (2.3-3.1) | 2.8 (2.4-3.3) | 2.2 (1.9-2.7) | 3.3 (2.8-3.8) | -.7(11)* | .9(9)* | 1.6(-.4-3.6)* | .12* |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 159 (69) | 156 (72) | 169(78) | 169(80) | 11 (88) | 14(97) | 4 (-14-22) | .68 |

| A1c | 8.2 (1.8) | 7.9 (1.8) | 8.3 (2.2) | 8.2 (2.3) | .1(2.0) | .3(2.4) | .2(-.3-.6) | .45 |

Note: N for the 36-month lipids variables was 458 and the means were based on the average of 24th, 30th and 36th month observations.

Based on arithmetic mean.

To achieve the treatment goals in both groups, the mean (SD) numbers of lipid-lowering and antihypertensive drugs used in the aggressive and standard treatment groups were 1.42 (.65) vs. 1.15 (.51) and 2.35 (1.33) vs. 1.62 (1.03), respectively. Rates of adverse events (AEs) and serious adverse events (SAEs) were low (Table 3). No difference was observed between groups in AEs related to lipid lowering drugs (p = .216), but more AEs related to BP drugs occurred in the aggressive group (p = .002). Orthostatic hypotension occurred in two participants in each group. One SAE judged to be possibly related to the interventions occurred in the standard group (hypotension) and four in the aggressive group (two hypotension and two hyperkalemia). All recovered after reduction or withdrawal of medication.

Table 3.

CVD Events and Adverse Events, by Randomization Group

| Aggressive (N = 252) | Standard (N = 247) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CVD EVENTS | |||

| Primary endpoint | 11 | 8 | .51 |

| Other CVD endpoints | 1 | 3 | .31 |

| Total CVD | 12 | 11 | .87 |

| Non-CVD deaths | 2 | 4 | .40 |

| ADVERSE EVENTS | |||

| Participants with AEs* | 97 (38.5%) | 66 (26.7%) | .005 |

| Related to lipid drugs | 46 (18.3%) | 35 (14.2%) | .216 |

| Related to BP drugs | 67 (26.6%) | 38 (15.4%) | .002 |

| Participants with SAEs* | 74 (29.4%) | 55 (22.3%) | .070 |

| Related to drugs | 4 | 1 |

Abbreviations: AE = adverse event; SAE = serious adverse event.

Note: Aggressive group primary events were 2 MI, 4 CABG/PTCA, 2 unstable angina, 1 definite stroke, 1 CHD death; the other CVD was a TIA. Standard group primary events were 2 MI, 4 CABG/PTCA, 1definite stroke, 1 CHD death; other CVD events were 2 possible nonfatal strokes and 1 SVT.

Outcomes

Primary CVD events occurred in 11 and 8 participants in the aggressive and standard treatment groups, respectively (p = .511) (Table 3). Other CV events and non-CVD death occurred in one vs. three and two vs. four participants in the two groups, respectively. The total number of CVD endpoints, either primary or secondary, did not differ significantly between treatment groups.

Carotid IMT progressed slightly in the standard treatment group and regressed in the aggressive group (Table 4). At 36 months, there was a significant difference between the standard vs. aggressive groups by both the worst-rank score method and t-test (both p < .0001). There were also significant differences in arterial mass (cross-sectional area, p < .0001 for both tests). Plaque score increased slightly in both groups at 36 months, with no difference between groups. Similarly, the percentage of individuals with at least one discrete plaque increased slightly in both groups at 36 months without significant intergroup difference.

Table 4.

Baseline and Follow-up Carotid and Cardiac Measures

| Aggressive | Standard | Group Difference | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| Carotid | ||||

|

IMT (mm) Baseline |

.810 (.19) |

.797 (.17) |

||

| 18 mo | .806 (.18) | .801 (.18) | ||

| 36 mo | .795 (.18) | .834 (.20) | ||

| Mean Change 18 mo | -.006 (.11) | .008 (.13) | .014 | .218* |

| Mean Change 36 mo | -.017 (.12)X | .041 (.14)+ | .058 | <.0001* |

|

Arterial Mass (mm2) Baseline |

17.36 (5.02) |

17.28 (4.55) |

||

| 18 mo | 17.04 (4.50) | 17.42 (4.42) | ||

| 36 mo | 17.14 (5.00) | 18.24 (4.95) | ||

| Mean Change 18 mo | -.16 (2.52) | .25 (2.98) | .41 | .131* |

| Mean Change 36 mo | -.14 (2.60) | 1.14 (2.70)+ | 1.29 | <.0001* |

|

Plaque Score Baseline |

1.85 (1.64) |

1.83 (1.56) |

||

| 18 mo | 2.07 (1.64) | 2.02 (1.58) | ||

| 36 mo | 2.40 (1.73) | 2.33 (1.71) | ||

| Mean Change 18 mo | .19 (1.10)+ | .19 (.89)+ | 0 | 1.00 |

| Mean Change 36 mo | .53 (1.22)+ | .50 (1.16)+ | .03 | .79 |

|

% Plaque Baseline |

74.6 |

76.4 |

||

| 18 mo | 82.5 | 80.4 | ||

| 36 mo | 88.9 | 84.3 | ||

| Point Change 18 mo | 7.9X | 4.0 | 3.9 | |

| Point Change 36 mo | 14.3+ | 7.9X | 6.4 | |

| Cardiac | ||||

|

LV mass (g) Baseline |

156.7 (38.3) |

156.1 (38.3) |

||

| 18 mo | 142.2 (33.6) | 147.2 (38.8) | ||

| 36 mo | 147.7 (36.2) | 150.9 (38.5) | ||

| Mean Change 18 mo | -14.7 (23.3)+ | -7.1 (26.3)+ | 7.6 | .002 |

| Mean Change 36 mo | -8.1(22.6)+ | -4.2 (22.4)+ | 3.9 | .069 |

|

LVM index (g/m2.7) Baseline |

41.2 (9.5) |

40.5 (8.5) |

||

| 18 mo | 37.4 (8.0) | 38.7 (9.3) | ||

| 36 mo | 38.6 (8.6) | 39.3 (8.4) | ||

| Mean Change 18 mo | -3.9 (6.2)+ | -1.7 (7.3)+ | 2.1 | .002 |

| Mean Change 36 mo | -2.4 (6.2)+ | -1.3 (6.0)+ | 1.2 | .050 |

|

EF Baseline |

60.5 (5.7) |

59.8 (5.8) |

||

| 18 mo | 59.8 (5.0) | 58.7 (6.3) | ||

| 36 mo | 59.7 (4.9) | 59.2 (5.6) | ||

| Mean Change 18 mo | -.9 (5.2)X | -1.2 (5.6)+ | .36 | .50 |

| Mean Change 36 mo | -.7 (5.3) | -.7 (5.6) | .04 | .93 |

P- values from the worst rank analyses for IMT were .691 and < .0001, and for arterial mass were .194 and < .0001 at 18 and 36 months, respectively.

Significant within-group change (p-value < .01).

Significant within-group change (p-value < .05).(Mihriye’s Nov 19 edit)

Abbreviations: EF = ejection fraction; IMT = intimal medial thickness; LV = left ventricular.

Changes in echocardiographic measures of LV structure (Table 4) also differed significantly between the aggressive and standard groups. LV mass and LV mass normalized for height2.7 decreased in both groups at 36 months, but to a greater degree in the aggressive treatment group (p = 0.069 and 0.050 respectively).

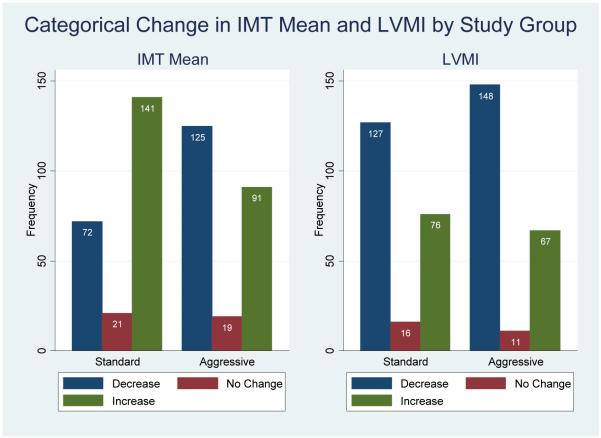

When both treatment groups were divided into those individuals whose measures decreased (improved), remained the same (± 0.01 mm for IMT or ± 0.5 gm/m2.7 for LVMI), or worsened over the treatment period (Figure 3), participants in the aggressive group were more likely to have a decrease in IMT (p < .0001) and a trend toward decreased LVMI (p = .25).

Figure 3. Categorical Changes in IMT Mean (a) and LVMI (b) by Randomization Group.

N for IMT data is 469, p-value <.0001. N for LVMI is 445, p-value = .25.

No change category was defined as ± 0.01 mm for IMT or ± 0.5 gm/m2.7 for LVMI.

Secondary Analyses

Intention-to-treat analyses compared groups stratified by pre-specified characteristics, including age, BMI, baseline LDL-C, non-HDL-C, baseline SBP, gender, A1c, smoking, CRP, and estimated glomerular filtration rate. No significant quantitative interactions were observed between treatment and any of the variables (Appendix Table A).

A sensitivity analysis was performed by evaluating IMT and LVMI changes in individuals in the aggressive group who achieved either the LDL-C goal of ≤ 70 mg/dL (n = 126) or SBP ≤ 115 mm Hg (n = 119) consistently during the last 6 months of the intervention compared with those in the standard treatment group. For IMT and arterial mass, there was a bigger difference in the adherent group compared to the whole aggressive group (Appendix Table B vs. Table 4) (changes of -.025 mm and -.39 mm2, respectively, both p < .0001 compared to the standard group). For differences in LVMI, there was only a marginally greater decrease (-2.7 g/m2.7 in the adherent group, p < .04 compared with the standard group). Participants achieving the aggressive SBP target had greater mean decreases in LVMI (-3.0 g/m2.7 in the adherent group, p < .01 vs. the standard group) compared with the aggressive group as a whole (Appendix Table B vs. Table 4).

Ordered logit analyses were performed on the combined cohort (Appendix Table C). The probability of a decrease in IMT was significantly related to decrease in LDL-C but not related to a decrease in SBP, even when the two factors were present in a combined model (p <.0005). Conversely, probability of decreases in LVMI were significantly related to decreases in SBP (p = .002) but not to LDL-C. In these models, age was a significant positive predictor of IMT increase, and BMI was a significant positive predictor of LVMI increase. To explore the time dependence of the treatment effects on changes in IMT and LVMI, regression models were run for the combined groups, with IMT or LVMI changes as dependent variables, including all other potential covariates plus the number of months the treatment goal was maintained for LDL-C, SBP, or both. The proportion of months at LDL-C goal or at both LDL-C and BP goals in the aggressive group was a significant determinant of IMT changes (p = .022 and p = .010, respectively). For LVMI, the proportion of months at BP or at both LDL-C and BP goals tended to be related to change in LVMI, but the trends were not significant.

COMMENT

This randomized trial in American Indian men and women with type 2 diabetes compared groups treated aggressively to target levels of LDL-C ≤ 70 mg/dL and SBP ≤ 115 mm Hg with a group treated to current LDL-C and SBP targets. The group treated to lower targets had an improvement (decrease) in IMT, whereas the standard treatment group had a worsening (increase) in IMT, a measure of atherosclerosis. There was also a greater decrease in LVMI in the aggressive group. Few CVD events occurred overall, with no intergroup difference.

This trial, the first to test predefined treatment targets for both LDL-C and SBP, answered several questions. First, it showed that lower targets for LDL-C and BP can be successfully and safely achieved. Previous trials of LDL-C lowering8 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 41 42 43 using fixed doses of statins showed reduced CVD in those achieving targets lower than the standard goals, but in none of these trials were lower targets pre-specified; thus those who achieved lower targets may have had lower LDL-C at baseline or may have been more adherent or responsive to the regimen. One previous trial that targeted DBP below standard goals achieved fewer CVD events in the aggressive treatment arm.41 In our trial both LDL-C and BP were treated to aggressive targets, low-dose aspirin therapy was maintained in the majority of both groups, and few individuals smoked.

We used surrogate endpoints for this trial because of a number of practical constraints, including the trial cost, rapidly evolving evidence in this field, and concern about the feasibility of conducting a long-term intervention in a vulnerable population. However, the endpoints selected have been validated as having prognostic significance for CVD events. Carotid ultrasound measures of IMT also have been validated against pathologic specimens. In addition, the carotid and echocardiographic measures used have been demonstrated to be potent predictors of CVD outcomes in the Strong Heart population of American Indians, which closely resembles the current cohort.29 Furthermore, at least twelve lipid lowering trials44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 have employed carotid ultrasound measures as endpoints and showed correlations between changes in carotid measures and reduction in CVD events.

Although the standard treatment group showed progression of carotid IMT, average IMT in the aggressive group decreased. This trial is one of the few to show regression of IMT.49 55 56 More commonly, clinical trials have observed less IMT progression in the treatment versus control group.46 47 54 57 58 59 60 61 This may suggest that intensive control of both lipids and BP may be necessary to reverse the atherosclerotic process. In contrast to IMT, plaque score and percentage of individuals with plaque did not differ between the two groups in the current study. These endpoints are less quantitative measures than IMT and reflect established atherosclerotic lesions. Thus, a longer period of therapy might be needed for improvement to be reflected in these measures of more advanced disease. More importantly, aggressive control of CVD risk factors at younger ages may prevent or retard development of advanced lesions.

LV hypertrophy and/or greater LVMI have been shown to predict CVD outcomes in both observational studies62 and clinical trials.63 64 Echocardiographic measures have not been used as commonly as surrogate endpoints in trials of risk factor reduction. However, lower echocardiographic LV mass and ECG estimates thereof during antihypertensive treatment have recently been shown to predict, independently of changes in BP and other covariates, lower rates of major cardiovascular events;63 64 as well as of incident heart failure,65 sudden death,66 and atrial fibrillation.67 Although LV mass measures declined in both groups, there was a significantly greater reduction in the aggressively treated group. Both treatment arms had normal mean LV ejection fraction upon study entry, and no changes were observed; a longer period of treatment would probably be necessary to detect a treatment effect in such a population.

Because we targeted both BP and lipid goals, the trial was not designed to distinguish which intervention was responsible for the improved measures of atherosclerosis and cardiac structure. Sensitivity analyses exploring the changes in those who met or exceeded LDL-C and SBP goals confirm the results of the intention-to-treat analyses, suggesting that the observed changes in endpoints could be attributable to the interventions on LDL-C and BP. Secondary analyses suggested that the IMT changes appeared to correlate more closely with the extent of lipid lowering. However, BP lowering also correlated with IMT changes, and it is difficult in secondary analyses to rule out confounding by compliance. Conversely, the changes in LVMI appeared more closely related to changes in SBP, although this analysis has the same limitation.

Additional analyses suggested that length of time at LDL-C and SBP targets in the aggressive group were determinants of both IMT and LVMI changes. Stratified analyses suggested that the effects were broadly applicable, regardless of age, obesity, gender, and baseline CVD risk factors.

An important finding was that few CVD events occurred in either treatment group. The rate of events in the combined sample was approximately 1.3 per 100 person-years. In the Strong Heart Study (SHS) population-based longitudinal follow-up of American Indians of comparable age with diabetes, CVD incidence rates were 2.8 to 3.6 per 100 person-years.27 68 In addition, progression of IMT in the standard treatment group in this trial was much lower than expected. A meta-analysis of trials using carotid IMT as an endpoint showed a 3-fold higher rate of progression in control groups than in our standard group,69 and rates of progression of IMT and LVMI in diabetic individuals of comparable ages in the SHS were also much higher (data not shown). Our findings may be the result of achieving defined targets in both groups at or better than current levels and the fact that all participants had frequent access to general medical care. In previous primary prevention studies that suggested major improvements in CVD rates at lower LDL-C targets resulting from statin therapy, BP was not controlled, aspirin use was low, and smoking rates tended to be higher. To our knowledge, no prior trials have had an SBP target as low as ≤ 115 mm Hg. In the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) trial, 41 the group in which DBP was lowered to 70 mm Hg had the lowest incidence of CVD events, although lipid levels were not targeted.

Our study suggests the possibility of incremental CV benefit of achieving more aggressive LDL-C and BP targets. Our data show significant retardation of atherosclerosis progression and regression of LV hypertrophy through more intensive therapy, suggesting that if these targets were achieved and sustained longer, incidence of CVD events would be reduced.

The strength of this study includes it being the first trial to test specific targets for both LDL-C and BP in individuals with diabetes. These targets were reached in each group, and adherence and follow-up were excellent. Subclinical ultrasound measures of atherosclerosis and cardiac function were assessed with standardized protocols. Observational data obtained using this methodology are available from a population-based sample of comparable diabetic American Indians,29 allowing comparison of progression rates as well as disease outcomes.

A reason to be cautious in interpreting this study is that only a single ethnic population was studied, American Indians. Although this group has high rates of CVD, their average LDL-C and BP levels are slightly lower than in other U.S. populations; other treat-to-target studies are needed to assess the safety and feasibility of achieving aggressive targets for LDL-C and BP in groups with higher levels. A second limitation is that surrogate endpoints were used. As the effectiveness of therapy improves and new treatment strategies are widely applied, it is becoming more difficult to conduct a trial in which adequate numbers of endpoints are achievable in a reasonable length of time for individuals without CVD at baseline. Thus, it may become increasingly important in the future to rely upon surrogate endpoints. We are planning an extended follow-up of these individuals to determine whether the improvements in atherosclerosis and cardiac structure are maintained in the aggressive group and whether they are reflected in fewer clinical CVD outcomes.

In conclusion, in this first trial to evaluate lower targets for both LDL-C and BP compared with standard targets in adults with diabetes, regression of IMT and greater decrease in LV mass were observed in the aggressive treatment group. Although there were no differences in clinical CVD outcomes, event rates were low in both groups, and progression of subclinical disease in the standard treatment group was lower than expected. The data suggest that targeted treatment of LDL-C and SBP improved surrogate measures of CVD, with greater benefits being attributable to the lower target levels. Whether these improvements will result in lower long-term CVD event rates or economic benefit remains to be determined.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Indian Health Service facilities, SANDS participants, and participating tribal communities for extraordinary cooperation and involvement without which this study would not have been possible: Tauqeer Ali, PhD; Colleen Begay; Stephanie Big Crow; Verna Cable; Damon Davis, RN; Lynne Dobrovolny, PA; Verdell Kanuho; Tanya Molina; Corinne Wills, CNP; and Jackie Yotter, RN, for coordination of study centers and Rachel Schaperow, MedStar Research Institute, Hyattsville, MD, for editing the manuscript. We also gratefully acknowledge donations of pharmacologic agents by First Horizon Pharmacy (Triglide); Merck and Co. (Cozaar/Hyzaar); and Pfizer, Inc. (Lipitor), and we thank Dr. John Lachin for providing advice on statistical methods.

Funding/Support: Funding was provided by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, NHLBI grant # 1U01 HL67031-01A1.

Role of the Sponsor: The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute has representation on the SANDS Steering Committee, which governed the design and conduct of the study, interpretation of the data, and preparation and approval of the manuscript. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Project Office reviewed the manuscript.

APPENDIX

Table A.

Change in IMT Mean (Columns 1-5) and LV Mass Index (Columns 6-10), by Strata of Baseline Characteristics

|

IMT (1) |

Aggressive (2) |

Standard (3) |

Group Dif. (4) |

p-val. (5) |

LVMI (6) |

Aggressive (7) |

Standard (8) |

Group Dif. (9) |

p-val. (10) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Inter. | N | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Inter. | |||

|

Age (yrs) <51 |

145 | -.010 (.12) | .046 (.12) | .05 | 140 | -3.43 (5.3) | -1.76 (5.5) | 1.67 | ||

| 51-60 | 173 | -.035 (.14) | .028 (.13) | .06 | .70 | 164 | -1.38 (6.5) | -.73 (6.9) | .65 | .86 |

| >60 | 151 | -.007 (.11) | .052 (.16) | .05 | 141 | -2.37 (6.7) | -1.46 (5.4) | .91 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) <30 | 146 | -.013 (.13) | .044 (.15) | .06 | 142 | -2.26 (5.2) | -1.96 (5.6) | .31 | ||

| 30-35 | 159 | -.019 (.14) | .029 (.14) | .05 | .64 | 151 | -2.84 (5.8) | -1.63 (5.5) | 1.21 | .28 |

| >35 | 163 | -.020 (.11) | .052 (.12) | .07 | 152 | -2.14 (7.4) | -.08 (7.0) | 2.06 | ||

| Gender Male | 159 | -.029 (.12) | .038 (.16) | .07 | .47 | 148 | -2.20 (5.2) | -.40 (5.9) | 1.8 | .35 |

| Female | 310 | -.011 (.13) | .042 (.13) | .05 | 297 | -2.50 (6.7) | -1.68 (6.1) | .82 | ||

| LDL-C (mg/dl) <100 | 222 | -.021 (.12) | .047 (.13) | .07 | 212 | -2.37 (6.6) | -1.33 (6.2) | 1.05 | ||

| 100-130 | 159 | -.011 (.12) | .040 (.12) | .05 | .94 | 135 | -2.61 (6.13) | -1.16 (6.27) | 1.44 | .72 |

| >130 | 81 | -.016 (.15) | .021 (.19) | .04 | 74 | -2.26 (5.6) | -1.05 (5.3) | 1.21 | ||

| Non-HDL (mg/dl) <130 | 194 | -.023 (.12) | .029 (.12) | .05 | 186 | -2.56 (6.4) | -1.35 (6.5) | 1.21 | ||

| 130-160 | 158 | -.012 (.12) | .057 (.13) | .07 | .85 | 151 | -3.01 (6.9) | -.91 (6.2) | 2.1 | .95 |

| >160 | 110 | -.010 (.14) | .030 (.18) | .04 | 101 | -1.44 (5.2) | -1.54 (5.2) | .10 | ||

| SBP (mm Hg) <120 | 129 | -.003 (.11) | .046 (.11) | .05 | 125 | -2.03 (6.3) | -2.28 (5.8) | .24 | ||

| 120-130 | 108 | -.019(.11) | .039 (.13) | .07 | .28 | 101 | -2.43 (6.7) | -.44 (6.7) | 1.99 | .59 |

| >130 | 231 | -.027 (.14) | .039 (.16) | .07 | 218 | -2.64(6.0) | -1.21 (5.8) | 1.44 | ||

| A1c <7 | 162 | -.027 (.12) | .042 (.14) | .07 | 153 | -2.27 (6.5) | -1.26 (5.6) | 1.00 | ||

| 7-8 | 107 | -.024 (.11) | .063 (.15) | .09 | .40 | 99 | -1.98 (7.0) | -2.26 (5.6) | .28 | .20 |

| >8 | 193 | -.010(.13) | .022 (.13) | .03 | 186 | -2.76 (5.7) | -.59(6.8) | 2.17 | ||

| CRP (mg/dl) <1.7 | 133 | -.009 (.10) | .053 (.17) | .06 | 127 | -2.30 (5.3) | -.33 (5.3) | 1.98 | ||

| 1.7-4.5 | 138 | -.032(.14) | .032(.12) | .06 | .41 | 128 | -2.05 (6.7) | -1.48 (6.9) | .57 | .66 |

| >4.5 | 142 | -.017(.13) | .041(.14) | .06 | 136 | -2.68 (5.4) | -2.09 (6.0) | .60 | ||

| eGFR <78 | 138 | .004 (.10) | .038 (.17) | .03 | 155 | -2.64(6.2) | .45(5.7) | 2.19 | ||

| 78-96 | 160 | -.023 (.13) | .040 (.12) | .06 | .53 | 151 | -2.56 (5.5) | -1.25 (6.7) | 1.32 | .09 |

| >96 | 161 | -.023(.13) | .041 (.13) | .06 | 155 | -2.64 (6.2) | -.45 (5.7) | 2.18 | ||

| Current smoker Yes | 96 | -.040(.16) | .045 (.14) | .09 | .22 | 87 | -1.96 (6.6) | -1.73 (7.6) | .23 | .38 |

| No | 373 | -.010(.11) | .040 (.14) | .05 | 358 | -2.51 (6.2) | -1.15 (5.6) | 1.45 |

Abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; CRP = c-reactive protein; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL-C = high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; IMT = intimal medial thickness; LDL-C = low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LV = left ventricular; SBP = systolic blood pressure.

Note: A non-parametric test of trend for the ranks of across-ordered groups was used for trends within groups. BMI exhibited a trend for LVMI within the standard group at p = .05. All other trends were non-significant. P-values for interaction terms were obtained by an ordinary least squares equation of IMT mean change variable on each variable of interest and its interaction with the treatment group, controlling for baseline IMT mean and data center.

Table B.

Baseline and Follow-up Carotid and Cardiac Measures: Participants who Achieved the LDL-C Goal of ≤ 70 (N = 126) or the SBP Goal of ≤ 115 (N = 119) vs the Standard Treatment Group

| LDL-C Goal | SBP Goal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adherent Aggressive |

Standard | Adherent Aggressive |

Standard | |||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p-value | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p-value | |

| Carotid | ||||||

| IMT (mm) Baseline |

.830 (.21) |

.797 (.17) |

.803(.21) |

.797 (.17) |

||

| 36 mo | .802 (.19) | .834 (.20) | .785 (.20) | .833 (.20) | ||

| Mean Change | -.025(.13) | .041 (.14) | <.001 | -.018(.12) | .041 (.14) | <.001 |

| Art. Mass Baseline |

18.1 (5.5) | 17.3(4.6) | 16.80(5.2) | 17.3(4.6) | ||

| 36 mo | 17.5(5.3) | 18.2 (5.0) | 16.6(5.0) | 18.2 (5.0) | ||

| Mean Change | -.39 (2.5) | 1.1 (2.7) | <.001 | -.32 (2.4) | 1.1 (2.7) | <.001 |

| Plaque Score Baseline |

2.02 (1.63) | 1.83 (1.56) | 1.76 (1.59) | 1.83 (1.56) | ||

| 36 mo | 2.58 (1.77) | 2.33 (1.71) | 2.27 (1.75) | 2.33 (1.71) | ||

| Mean Change | .54(1.14) | .50 (1.16) | .73 | .50 (1.10) | .50 (1.16) | .97 |

| % Plaque Baseline |

78.6 | 76.4 | .64 | 73.1 | 76.4 | .49 |

| 36 mo | 89.5 | 84.3 | .17 | 86.2 | 84.3 | .63 |

| Percentage Point Difference | 10.9 | 7.9 | 13.1 | 7.9 | ||

| Cardiac | ||||||

| LV Mass (g) Baseline |

160.2(40.1) | 156.1(38.3) | 155.7(38.3) | 156.1(38.3) | ||

| 36 mo | 150.5(37.5) | 150.9(38.5) | 144.8(36.6) | 150.9(38.5) | ||

| Mean Change | -8.8 (24.7) | -4.2 (22.4) | .08 | -10.1(22.3) | -4.2 (22.4) | .02 |

| LVMI(g/m2.7) Baseline |

41.8 (9.2) | 40.6 (8.5) | 40.7 (9.3) | 40.6 (8.5) | ||

| 36 mo | 39.0 (8.2) | 39.3(8.4) | 37.6 (8.2) | 39.3 (8.4) | ||

| Mean Change | -2.7 (6.7) | -1.3(6.0) | .04 | -3.0 (5.9) | -1.3 (6.1) | .01 |

| EF (%) Baseline |

60.5 (5.9) | 59.8 (5.8) | 60.5 (5.0) | 59.8 (5.8) | ||

| 36 mo | 60.2 (4.5) | 59.2(5.6) | 60.0 (4.6) | 59.2 (5.6) | ||

| Mean Change | -.17 (5.8) | -.70 (5.6) | .41 | -.43 (4.2) | -.70 (5.6) | .46 |

Table C.

Ordered Logistic Regression Analyses of Determinants of Change Category for IMT and LV Mass Index Between Baseline and 36 Months

| MODELS | 1. With Change in LDL-C | 2. With Change in SBP | 3. With Changes in LDL-C and SBP |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (SE) | p-value | Coefficient (SE) | p- value |

Coefficient (SE) | p-value | |

| Dependent Variable: IMT Change Category* | ||||||

| Baseline IMT mean | -3.82 (0.71) | .000 | -3.88 (0.69) | .000 | -3.84 (0.72) | .000 |

| Change in LDL-C | 0.008 (0.0025) | .002 | 0.007 (0.003) | .005 | ||

| Change in SBP | 0.008 (0.005) | .127 | 0.005 (0.006) | .345 | ||

| Age | 0.029 (0.012) | .016 | 0.032 (0.012) | .006 | 0.030 (0.012) | .012 |

| BMI | 0.014 (0.015) | .38 | 0.019 (.015) | .214 | 0.016 (0.0016) | .29 |

| N | 445 | 458 | 444 | |||

| LR chi-sq | 54.2 | .000 | 50.4 | .000 | 56.3 | .000 |

| Dependent Variable: LV Mass Index Change Category | ||||||

| Baseline LV mass | -0.096 (.015) | .000 | -0.105 (0.016) | .000 | -0.101 (0.016) | .000 |

| Change in LDL-C | 0.006 (0.003) | .042 | 0.004 (0.003) | .169 | ||

| Change in SBP | 0.021 (0.006) | .001 | 0.020 (0.006) | .002 | ||

| Age | 0.014 (0.012) | .24 | 0.015 (0.012) | .20 | 0.019 (0.012) | .13 |

| BMI | 0.078 (0.019) | .000 | 0.095 (0.020) | .000 | 0.091(0.020) | .000 |

| N | 423 | 436 | 422 | |||

| LR chi-sq | 57.5 | .000 | 72.4 | .000 | 70.4 | .000 |

Change Categories: 1 = Decrease, 2 = No Change, 3 = Increase

Note: Gender and site were not significant.

Abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; IMT = intimal medial thickness; LDL-C = low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LR chi-sq = Likelihood ratio chi-square statistic for the overall model; LV = left ventricular; SBP = systolic blood pressure.

Footnotes

Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT00047424, http://clinicaltrials.gov/

Federal Government/IHS Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Indian Health Service, the Office of Public Health and Science, or the National Institutes of Health.

Financial Disclosure: Medications were donated by: First Horizon Pharmacy, Triglide; Merck and Co., Cozaar/Hyzaar; Pfizer, Inc., Lipitor. Dr. Howard has served on the advisory boards of Merck, Shering Plough, the Egg Nutrition Council, and General Mills, and has received research support from Merck and Pfizer. The other authors have nothing to declare.

Independent Statistical Analyses: Statistical analysis was performed by statisticians at MedStar, under the direction of Dr. Barbara V. Howard, PhD, and the direction of Nawar Shara, PhD, department chair, and by statisticians at the University of Oklahoma under the direction of Dr. Elisa T. Lee.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kannel WB, McGee DL. Diabetes and glucose tolerance as risk factors for cardiovascular disease: The Framingham Study. Diabetes Care. 1979;2:120–126. doi: 10.2337/diacare.2.2.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kleinman JC, Donahue RP, Harris MI, et al. Mortality among diabetics in a national sample. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;128:389–401. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butler WJ, Ostrander LD, Can11an WJ, et al. Mortality from coronary heart disease in the Tecumseh Study: Long-term effect of diabetes mellitus, glucose tolerance and other risk factors. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;121:541–547. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howard BV. Macrovascular complications of diabetes mellitus. In: LeRoith D, Taylor SI, Olefs JM, editors. Diabetes Mellitus. Lippincott-Raven; Philadelphia: 1996. pp. 792–797. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klein R. Kelly West Lecture 1994: Hyperglycemia and microvascular and macrovascular disease in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:258–268. doi: 10.2337/diacare.18.2.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults Executive Summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure . The sixth report of the Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC VI) 1997. NIH Publication No. 98-4080. [No. 98-4080] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cannon CP, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, Rader DJ, Rouleau JL, Belder R, Joyal SV, Hill KA, Pfeffer MA, Skene AM, Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 22 Investigators Intensive versus moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1495–504. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pyǒrälä K, Pedersen TR, Kjekshus J, Faergeman O, Olsson AG, Thorgeirsson G, A subgroup analysis of the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S) Cholesterol lowering with simvastatin improves prognosis of diabetic patients with coronary heart disease. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:614–20. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.4.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sacks FM, Pfeffer MA, Moye LA, Rouleau JL, Rutherford JD, Cole TG, Brown L, Warnica JW, Arnold JM, Wun CC, Davis BR, Braunwald E, Cholesterol and Recurrent Events Trial investigators The effect of pravastatin on coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1001–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610033351401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keech A, Colquhoun D, Best J, Kirby A, Simes RJ, Hunt D, Hague W, Beller E, Arulchelvam M, Baker J, Tonkin A, LIPID Study Group Secondary prevention of cardiovascular events with long-term pravastatin in patients with diabetes or impaired fasting glucose: results from the LIPID trial. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2713–21. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.10.2713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubins HB, Robins SJ, Collins D, Nelson DB, Elam MB, Schaefer EJ, Faas FH, Anderson JW. Diabetes, plasma insulin, and cardiovascular disease: subgroup analysis from the Department of Veterans Affairs high-density lipoprotein intervention trial (VA-HIT) Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2597–604. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.22.2597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pedersen TR, Faergeman O, Kastelein JJ, Olsson AG, Tikkanen MJ, Holme I, Larsen ML, Bendiksen FS, Lindahl C, Szarek M, Tsai J, Incremental Decrease in End Points Through Aggressive Lipid Lowering (IDEAL) Study Group High-dose atorvastatin vs. usual-dose simvastatin for secondary prevention after myocardial infarction: the IDEAL study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294:2437–45. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.19.2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shepherd J, Barter P, Carmena R, Deedwania P, Fruchart JC, Haffner S, Hsia J, Breazna A, LaRosa J, Grundy S, Waters D. Effect of lowering LDL cholesterol substantially below currently recommended levels in patients with coronary heart disease and diabetes: the Treating to New Targets (TNT) study. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1220–6. doi: 10.2337/dc05-2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9326):7–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09327-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Serruys PW, de Feyter P, Macaya C, Kokott N, Puel J, Vrolix M, Branzi A, Bertolami MC, Jackson G, Strauss B, Meier B, Lescol Intervention Prevention Study (LIPS) Investigators Fluvastatin for prevention of cardiac events following successful first percutaneous coronary intervention: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;287:3215–22. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.24.3215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoogwerf BJ, Waness A, Cressman M, Canner J, Campeau L, Domanski M, Geller N, Herd A, Hickey A, Hunninghake DB, Knatterud GL, White C. Effects of aggressive cholesterol lowering and low-dose anticoagulation on clinical and angiographic outcomes in patients with diabetes: the Post Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Trial. Diabetes. 1999;48:1289–94. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.6.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shepherd J, Blauw GJ, Murphy MB, Bollen EL, Buckley BM, Cobbe SM, Ford I, Gaw A, Hyland M, Jukema JW, Kamper AM, Macfarlane PW, Meinders AE, Norrie J, Packard CJ, Perry IJ, Stott DJ, Sweeney BJ, Twomey C, Westendorp RG, PROSPER study group PROspective Study of Pravastatin in the Elderly at Risk. Pravastatin in elderly individuals at risk of vascular disease (PROSPER): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:1623–30. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11600-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collins R, Armitage J, Parish S, Sleigh P, Peto R, Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol-lowering with simvastatin in 5963 people with diabetes: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361:2005–16. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13636-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Colhoun HM, Betteridge DJ, Durrington PN, Hitman GA, Neil HA, Livingstone SJ, Thomason MJ, Mackness MI, Charlton-Menys V, Fuller JH, CARDS investigators Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with atorvastatin in type 2 diabetes in the Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study (CARDS): multicentre randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:685–96. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16895-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Downs JR, Clearfield M, Weis S, Whitney E, Shapiro DR, Beere PA, Langendorfer A, Stein EA, Kruyer W, Gotto AM., Jr. Primary prevention of acute coronary events with lovastatin in men and women with average cholesterol levels: results of AFCAPS/TexCAPS. Air Force/Texas Coronary Atherosclerosis Prevention Study. JAMA. 1998;279:1615–22. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.20.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sever PS, Poulter NR, Dahlöf B, Wedel H, Collins R, Beevers G, Caulfield M, Kjeldsen SE, Kristinsson A, McInnes GT, Mehlsen J, Nieminen M, O’Brien E, Ostergren J. Reduction in cardiovascular events with atorvastatin in 2,532 patients with type 2 diabetes: Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial--lipid-lowering arm (ASCOT-LLA) Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1151–7. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.5.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knopp RH, d’Emden M, Smilde JG, Pocock SJ. Efficacy and safety of atorvastatin in the prevention of cardiovascular end points in subjects with type 2 diabetes: the Atorvastatin Study for Prevention of Coronary Heart Disease Endpoints in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (ASPEN) Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1478–85. doi: 10.2337/dc05-2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial. Major outcomes in moderately hypercholesterolemic, hypertensive patients randomized to pravastatin vs usual care: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT-LLT) JAMA. 2002 Dec 18;288(23):2998–3007. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.23.2998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koskinen P, Mänttäri M, Manninen V, Huttunen JK, Heinonen OP, Frick MH. Coronary heart disease incidence in NIDDM patients in the Helsinki Heart Study. Diabetes Care. 1992 Jul;15(7):820–5. doi: 10.2337/diacare.15.7.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Viberti G, Mogensen CE, Groop LC, Pauls JF, European Microalbuminuria Captopril Study Group Effect of captopril on progression to clinical proteinuria in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and microalbuminuria. JAMA. 1994;271:275–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Howard BV, Lee ET, Cowan LD, et al. Rising tide of cardiovascular disease in American Indians: The Strong Heart Study. Circulation. 1999;99:2389–2395. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.18.2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Howard BV, Robbins DC, Sievers ML, Lee ET, Rhoades D, Devereux RB, Cowan LD, Gray RS, Welty TK, Go OT, Howard WJ. LDL cholesterol as a strong predictor of coronary heart disease in diabetic individuals with insulin resistance and low LDL. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:830–5. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.3.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silverman A, Huang DJ, Russell M, Mete M, Roman MJ, Sylianou M, et al. Stop Atherosclerosis in Native Diabetics Study (SANDS): Baseline Characteristics of the Randomized Cohort. Ethnicity and Health. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Russell M. Examination of lower targets for low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and blood pressure in diabetes--the Stop Atherosclerosis in Native Diabetics Study (SANDS) Am Heart J. 2006;152:867–875. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Indian Health Manual (IHM) 2-1.2. http://www.ihs.gov/PublicInfo/Publications/IHSManual/Part2/pt2chapt1/pt2chpt1.htm#2.

- 32.Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. :1183–97. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.7.1183. 199720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med. 1998;15:539–53. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199807)15:7<539::AID-DIA668>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, et al. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Circulation. 2004;110:227–239. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133317.49796.0E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Allain CC, Poon LS, Chan CS, et al. Enzymatic determination of total serum cholesterol. Clin Chem. 1974;20:470–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics, a Johnson & Johnson company. Cholesterol. 2000 Mar;:1–10. Pub No. MP2-35. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Devereux RB, Roman MJ. Evaluation of cardiac and vascular structure by echocardiography and other nonivasive techniques. In: Laragh JH, Brenner BM, editors. Hypertension: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Management. 2nd ed. Raven Press; New York: 1995. pp. 1969–85. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roman MJ, Pickering TG, Schwartz JE, Pini R, Devereux RB. Relation of arterial structure and function to left ventricular geometric patterns in hypertensive adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28:751–756. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(96)00225-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zoghbi WA, Enriquez-Sarano M, Foster E, Grayburn PA, Kraft CD, Levine RA, Nihoyannopoulos P, Otto CM, Quinones MA, Rakowski H, Stewart WJ, Waggoner A, Weissman NJ, American Society of Echocardiography Recommendations for evaluation of the severity of native valvular regurgitation with two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2003;16:777–802. doi: 10.1016/S0894-7317(03)00335-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quinones MA, Otto CM, Stoddard M, et al. Recommendations for quantification of Doppler echocardiography: a report from the Doppler quantification task force of the nomenclature and standards committee of the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2001;15:167–184. doi: 10.1067/mje.2002.120202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wei LJ, Lachin JM. Two-sample asymptotically distribution-free tests for incomplete multivariate observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1984;79:1151–1170. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, Dahlöf B, Elmfeldt D, Julius S, Ménard J, Rahn KH, Wedel H, Westerling S, HOT Study Group Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trial. Lancet. 1998;351:1755–62. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)04311-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Estacio RO, Jeffers BW, Gifford N, Schrier RW. Effect of blood pressure control on diabetic microvascular complications in patients with hypertension and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(Suppl 2):B54–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patel A, ADVANCE Collaborative Group. MacMahon S, Chalmers J, Neal B, Woodward M, Billot L, Harrap S, Poulter N, Marre M, Cooper M, Glasziou P, Grobbee DE, Hamet P, Heller S, Liu LS, Mancia G, Mogensen CE, Pan CY, Rodgers A, Williams B. Effects of a fixed combination of perindopril and indapamide on macrovascular and microvascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (the ADVANCE trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;370:829–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61303-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blankenhorn DH, Selzer RH, Crawford DW, Barth JD, Liu CR, Liu CH, Mack WJ, Alaupovic P. Beneficial effects of colestipol-niacin therapy on the common carotid artery. Two- and four-year reduction of intima-media thickness measured by ultrasound. Circulation. 1993;88:20–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Furberg CD, Adams HP, Jr, Applegate WB, Byington RP, Espeland MA, Hartwell T, Hunninghake DB, Lefkowitz DS, Probstfield J, Riley WA, et al. Asymptomatic Carotid Artery Progression Study (ACAPS) Research Group Effect of lovastatin on early carotid atherosclerosis and cardiovascular events. Circulation. 1994;90:1679–87. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.4.1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Crouse JR, 3rd, Byington RP, Bond MG, Espeland MA, Craven TE, Sprinkle JW, McGovern ME, Furberg CD. Pravastatin, Lipids, and Atherosclerosis in the Carotid Arteries (PLAC-II) Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:455–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80580-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Salonen R, Nyyssönen K, Porkkala E, Rummukainen J, Belder R, Park JS, Salonen JT. Kuopio Atherosclerosis Prevention Study (KAPS). A population-based primary preventive trial of the effect of LDL lowering on atherosclerotic progression in carotid and femoral arteries. Circulation. 1995;92:1758–64. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.7.1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mercuri M, Bond MG, Sirtori CR, Veglia F, Crepaldi G, Feruglio FS, Descovich G, Ricci G, Rubba P, Mancini M, Gallus G, Bianchi G, D’Alò G, Ventura A. Pravastatin reduces carotid intima-media thickness progression in an asymptomatic hypercholesterolemic mediterranean population: the Carotid Atherosclerosis Italian Ultrasound Study. Am J Med. 1996;101:627–34. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(96)00333-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hodis HN, Mack WJ, LaBree L, Selzer RH, Liu C, Liu C, Alaupovic P, Kwong-Fu H, Azen SP. Reduction in carotid arterial wall thickness using lovastatin and dietary therapy: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124(6):548–56. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-6-199603150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.MacMahon S, Sharpe N, Gamble G, Hart H, Scott J, Simes J, White H, LIPID Trial Research Group Effects of lowering average of below-average cholesterol levels on the progression of carotid atherosclerosis: results of the LIPID Atherosclerosis Substudy. Circulation. 1998;97:1784–90. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.18.1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Groot E, Jukema JW, Montauban van Swijndregt AD, Zwinderman AH, Ackerstaff RG, van der Steen AF, Bom N, Lie KI, Bruschke AV. B-mode ultrasound assessment of pravastatin treatment effect on carotid and femoral artery walls and its correlations with coronary arteriographic findings: a report of the Regression Growth Evaluation Statin Study (REGRESS) J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:1561–7. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00170-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smilde TJ, van Wissen S, Wollersheim H, Trip MD, Kastelein JJ, Stalenhoef AF. Effect of aggressive versus conventional lipid lowering on atherosclerosis progression in familial hypercholesterolaemia (ASAP): a prospective, randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet. 2001;357:577–81. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Taylor AJ, Kent SM, Flaherty PJ, Coyle LC, Markwood TT, Vernalis MN. ARBITER: Arterial Biology for the Investigation of the Treatment Effects of Reducing Cholesterol: a randomized trial comparing the effects of atorvastatin and pravastatin on carotid intima medial thickness. Circulation. 2002;106:2055–60. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000034508.55617.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Taylor AJ, Sullenberger LE, Lee HJ, Lee JK, Grace KA. Arterial Biology for the Investigation of the Treatment Effects of Reducing Cholesterol (ARBITER) 2: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of extended-release niacin on atherosclerosis progression in secondary prevention patients treated with statins. Circulation. 2004;110:3512–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000148955.19792.8D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Crouse JR, 3rd, Raichlen JS, Riley WA, Evans GW, Palmer MK, O’Leary DH, Grobbee DE, Bots ML, METEOR Study Group Effect of rosuvastatin on progression of carotid intima-media thickness in low-risk individuals with subclinical atherosclerosis: the METEOR Trial. JAMA. 2007;297:1344–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.12.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mack WJ, Selzer RH, Hodis HN, Erickson JK, Liu CR, Liu CH, Crawford DW, Blankenhorn DH. One-year reduction and longitudinal analysis of carotid intima-media thickness associated with colestipol/niacin therapy. Stroke. 1993 Dec;24(12):1779–83. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.12.1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Borhani NO, Mercuri M, Borhani PA, Buckalew VM, Canossa-Terris M, Carr AA, Kappagoda T, Rocco MV, Schnaper HW, Sowers JR, Bond MG. Final outcome results of the Multicenter Isradipine Diuretic Atherosclerosis Study (MIDAS). A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1996;276:785–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zanchetti A, Bond MG, Hennig M, Neiss A, Mancia G, Dal Palù C, Hansson L, Magnani B, Rahn KH, Reid JL, Rodicio J, Safar M, Eckes L, Rizzini P, European Lacidipine Study on Atherosclerosis investigators Calcium antagonist lacidipine slows down progression of asymptomatic carotid atherosclerosis: principal results of the European Lacidipine Study on Atherosclerosis (ELSA), a randomized, double-blind, long-term trial. Circulation. 2002;106:2422–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000039288.86470.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lonn E, Yusuf S, Dzavik V, Doris C, Yi Q, Smith S, Moore-Cox A, Bosch J, Riley W, Teo K, SECURE Investigators Effects of ramipril and vitamin E on atherosclerosis: the study to evaluate carotid ultrasound changes in patients treated with ramipril and vitamin E (SECURE) Circulation. 2001;103:919–25. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.7.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hedblad B, Wikstrand J, Janzon L, Wedel H, Berglund G. Low-dose metoprolol CR/XL and fluvastatin slow progression of carotid intima-media thickness: Main results from the Beta-Blocker Cholesterol-Lowering Asymptomatic Plaque Study (BCAPS) Circulation. 2001;103:1721–6. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.13.1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Roman MJ, Alderman MH, Pickering TG, Pini R, Keating JO, Sealey JE, Devereux RB. Differential effects of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition and diuretic therapy on reductions in ambulatory blood pressure, left ventricular mass, and vascular hypertrophy. Am J Hypertens. 1998;(4 Pt 1):387–96. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(97)00492-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vakili BA, Okin PM, Devereux RB. Prognostic significance of left ventricular hypertrophy. Am Heart J. 2001;141:334–341. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.113218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Devereux RB, Wachtell K, Gerdts E, Boman K, Nieminen MS, Papademetriou V, Rokkedal J, Harris K, Aurup P, Dahlöf B. Prognostic significance of left ventricular mass change during treatment of hypertension. JAMA. 2004;292:2350–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.19.2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Okin PM, Devereux RB, Jern S, Kjeldsen SE, Julius S, Nieminen MS, Snapinn S, Harris KE, Aurup P, Edelman JM, Wedel H, Lindholm LH, Dahlöf B, LIFE Study Investigators Regression of electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy during antihypertensive treatment and the prediction of major cardiovascular events. JAMA. 2004;292:2343–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.19.2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Okin PM, Devereux RB, Harris KE, Jern S, Kjeldsen SE, Julius S, Edelman JM, Dahlöf B, LIFE Study Investigators Regression of electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy is associated with less hospitalization for heart failure in hypertensive patients. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:311–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-5-200709040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wachtell K, Okin PM, Olsen MH, Dahlöf B, Devereux RB, Ibsen H, Kjeldsen SE, Lindholm LH, Nieminen MS, Thygesen K. Regression of electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy during antihypertensive therapy and reduction in sudden cardiac death: the LIFE Study. Circulation. 2007;116:700–5. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.666594. Epub 2007 Jul 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Okin PM, Wachtell K, Devereux RB, Harris KE, Jern S, Kjeldsen SE, Julius S, Lindholm LH, Nieminen MS, Edelman JM, Hille DA, Dahlöf B. Regression of electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy and decreased incidence of new-onset atrial fibrillation in patients with hypertension. JAMA. 2006;296:1242–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.10.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lee ET, Cowan LD, Welty TK, Sievers M, Howard WJ, Oopik A, Wang W, Yeh J, Devereux RB, Rhoades ER, Fabsitz RR, Go O, Howard BV. All-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease mortality in three American Indian populations, aged 45-74 years, 1984-1988. The Strong Heart Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147:995–1008. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Espeland MA, O’Leary DH, Terry JG, Morgan T, Evans G, Mudra H. Carotid intimal-media thickness as a surrogate for cardiovascular disease events in trials of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. Curr Control Trials Cardiovasc Med. 2005;6:3. doi: 10.1186/1468-6708-6-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]