Abstract

In many rural regions of developing countries, natural resource dependency means changes in climate patterns hold tremendous potential to impact livelihoods. When environmentally-based livelihood options are constrained, migration can become an important adaptive strategy. Using data from the Mexican Migration Project, we model U.S. emigration from rural communities as related to community, household and climate factors. The results suggest that households subjected to recent drought conditions are far more likely to send a U.S. migrant, but only in communities with strong migration histories. In regions lacking such social networks, rainfall deficits actually reduce migration propensities, perhaps reflecting constraints in the ability to engage in migration as a coping strategy. Policy implications emphasize diversification of rural Mexican livelihoods in the face of contemporary climate change.

Variability associated with climate change will most likely increase the frequency and severity of natural disasters such as hurricanes (Trenberth et al. 2007) and more prolonged, lower-intensity events such as droughts (Kundzewicz 2007). Both of these phenomena might alter patterns of human migration (e.g., Gutmann and Field 2010), an issue that has increasingly garnered attention among the public as well as in policy and academic realms (Hartmann 2010). Our analytical focus is on Mexico-U.S. migration, one of the largest and longest-sustained international flows of people in the world (Massey and Sana 2003) and the main source of both legal and undocumented migration into the U.S. (Passel and Cohn 2011). Even so, only a handful of peer-reviewed studies exist on potential environmental factors shaping Mexico-U.S. migration.

Most scholars contend that climate change will likely increase mobility within a nation’s borders rather than create a wave of international “climate refugees” (e.g., Bardsley and Hugo 2010; Hartmann 2010). Yet, the association between climatic variability and migration distance is contingent on factors such as household socioeconomic status (Gray 2009, Gray and Mueller 2012a, 2012b). Further, internal or international migrant networks play a key role in determining whether people move within or across national boundaries in response to economic conditions (Lindstrom and Lauster 2001). In the Mexican setting, a strong association has been identified between migrant networks and migration (Massey and Riosmena 2010) especially from rural areas (Fussell and Massey 2004). Likewise, prior migration experience within the household decreases the uncertainty surrounding, and costs associated with, subsequent migration thereby facilitating mobility (e.g., Massey and Espinosa 1997). As such, we argue migrant networks and prior migration experience will be important mediators on whether migration is used as an adaptation strategy to economic and social vulnerability associated with climatic stress and variability.

To test the association between broad availability of migrant networks, U.S.-bound migration and environmental stress and variability, we model the association between variation in state-level rainfall and U.S.-bound migration from Mexico’s historical sending regions as contrasted with other regions. We use data from 66 rural communities surveyed by the Mexican Migration Project (MMP). Although substantial research has examined the social, economic, and policy drivers of Mexican migration to the U.S. (e.g., Angelucci, forthcoming; Hamilton and Villarreal 2011; Lindstrom and Lauster 2001; Massey et al. 1987; Massey and Espinosa 1997), less is known about the environmental dimensions of migration streams.

Theoretical Perspectives on Migration-Environment Linkages

A special issue of Global Environmental Change (Black et al. 2011a) presented a useful comprehensive conceptual framework and also brought together several empirical contributions to the migration-environment literature. The framework, by Black et al. (2011b), “steps back to consider major migration theories” including neoclassical, social capital, and the new economics of labor migration, while also integrating environmental factors. Commonly understood migration predictors – such as employment opportunities, family/kin obligations, and political conflict/insecurity – are shown to be indirectly influenced by environmental factors. In addition, spatial and temporal variability in environmental influences are considered since environmental shocks may be cyclical (e.g., seasonal monsoons), short-term (e.g., hurricane), or more gradual in their development (e.g., drought).

Also useful within our work is the Sustainable Rural Livelihoods Framework (IFAD 2010) which classifies “capital assets” that shape livelihood options including human (e.g., labor), financial (e.g., savings), physical (e.g., automobiles), social (e.g., support networks), and natural capital (e.g., wild foods and fuels). The relative availability of various assets is further impacted by individual and household actions as well as broader socioeconomic-political structures and processes. In turn, differential capital availability shapes livelihood strategies which may include how households allocate human capital across space (e.g., labor migration, see Collinson et al. 2006) or how they use natural capital (e.g., resource-based crafts for market, Pereira, Shackleton and Shackleton 2006).

Within both the framework by Black et al. (2011b) and Sustainable Livelihoods, natural capital holds a prominent position in livelihood and migration decision-making – albeit sometimes acting as an indirect influence. Such centrality is logical since in rural regions of developing nations, proximate natural resources are often essential in meeting basic living requirements and responding to household stress and shocks (e.g., Hunter, Twine and Patterson 2007). In rural Mexico, environmental change has immediate and direct impacts on the health and well-being (Koziell and Saunders 2001) since it shapes vulnerability through impacts on agricultural productivity (Eakin 2005; Feng et al. 2010; Skoufias and Vinha 2013).

Previous Empirical Studies

Livelihood diversification reduces household vulnerability (Ellis 2000; Skoufias and Vinha 2013) and migration is a particular adaptation strategy used by households facing environmental strain (Bilsborrow 1992; de Sherbinin et al. 2008; McLeman and Hunter 2010; Njock and Westlund 2010). In this way, changes in proximate natural capital shape household decisions about use of human capital.

There is empirical evidence of this association from rural areas across the globe. Massey, Axinn and Ghimire (2010) find that environmental factors play a role in migration in Nepal, particularly short-distance moves. Similar results emerge in Burkina Faso (Henry, Schoumaker and Beauchemin 2004) where residents of drier regions are more likely to engage in both temporary and permanent migrations to other rural areas as compared to residents of high-precipitation regions. During a severe drought in 1983–1985 Mali, too, experienced an increase in short-term cyclical migration and the migration of women and children (Findley 1994). Lower natural capital in the form of smaller fish catches also intensified livelihood vulnerability in East Africa, resulting in the migration of fisherfolk (Njock and Westlund 2010).

Although these results are consistent with the notion that migration increases in times of “environmental scarcity,” others hypothesize that vulnerability can actually constrain migration, particularly costly long-distance moves. In rural Bangladesh, for example, disasters actually reduce mobility through heightened resource constraints (Gray and Mueller 2012a). Further, crop failure and flooding are more likely to propel migration among women who have less secure access to land in this setting.

Finally, the “environmental capital” hypothesis finds support in other research. In rural Ecuador, for example, land provides capital that can facilitate migration (Gray 2010). Studies in villages of the Kayes area, Mali, also observed that relatively more advantaged households were willing to invest a sizable amount of resources to send migrants given the prospect of increasing wealth through remittances and thus, reinforce their social status (Azam and Gubert 2006).

As mentioned at the outset, there is little work on how rural Mexican households might respond to natural capital shocks (i.e., climatic variability) using U.S.-bound migration as an adaptation strategy. We draw on three existing studies. Seminal work by Munshi (2003) made use of an earlier version of the MMP sample in rural areas of historical sending regions. The analysis used precipitation patterns as an instrumental variable to predict the size of the international migrant network available to residents of rural sending communities. The focus of that project was the effect of networks on Mexican migrant wages in the U.S. and, indeed, networks exhibit a positive effect on employment and wages (Munshi 2003). But examination of the rainfall effects shows higher levels of recent precipitation are negatively associated with proportions of recent migrants (1–3 years) in a given migrant network. In other words, periods likely characterized by higher agricultural productivity (with more rainfall) exhibit less emigration. This suggests recent drought, and thereby intensified agricultural vulnerability, may push U.S. bound migrants.

Other research examines Mexican migration at scales coarser than the household. Using data from the 2000 Census and the 2005 Population Count, Feng et al. (2010) found a negative association between crop yields (as a proxy of the confluence of climatic shifts and structural conditions) and state-level U.S. migration rates, particularly for the most rural states (Feng and Oppenheimer 2012). Also using the 2000 Mexican Census, Saldaña-Zorilla and Sandberg (2009) found that local vulnerability to natural disasters was associated with municipal out-migration. Here, dimensions of vulnerability included absence of credit and associated declines in income. Related to this institutional focus, Eakin (2005) argues that migration, as a livelihood adaptation strategy, must be seen as a product of not only climatic forces but also rising production costs, decreasing producer subsidies and obstacles in access to commercial agricultural markets. In this way, institutional changes are key to understanding migration and rural vulnerabilities to climate change (see also Liverman 1990, 2001).

Rural Mexican Context: Trends and Patterns in Livelihoods and Migration

Rural Livelihoods

Rural Mexican livelihoods are particularly vulnerable to weather stress and shocks given the high level of agricultural dependence. Using data from four communities, Wiggins et al. (2002) found that 78% of households farmed, predominantly maize and beans.1 Also testifying to the importance of rainfall within rural Mexican agriculture, approximately 82% of cultivated land is rainfed (INEGI 2007), thereby highly susceptible to both short- and longer-term weather fluctuations (Conde, Ferrer, and Orozco 2006; Endfield 2007). Indeed, Appendini and Liverman (1994) estimate that droughts are responsible for more than 90% of all crop losses in Mexico. Off-farm employment and migration appear to stabilize rural livelihoods through diversification and reduced environmental reliance (De Janvry and Sadoulet 2001) with such diversification also insuring against income risks arising from crop price fluctuations (Stark and Bloom 1985).

Rural livelihood diversification and institutional failure have become particularly relevant in recent times given economic restructuring and changes in the Mexican political economy disproportionately affecting the countryside. Studies have documented the negative implications of the nation’s global economic integration for Mexico’s smallholder farmers (Eakin 2005). After decades of public investment and supportive, protective agricultural policies spurring agricultural growth, liberalization of the agricultural sector and food policy during the Salinas de Gortari administration (1988–1994) brought dramatic and longstanding changes to the countryside. Such changes further concentrated poverty in rural places as agricultural employment diminished considerably and commodity prices declined (e.g., Nevins 2007). These changes, paired with increases in foreign direct investment and employment in (maquiladora) manufacturing helped exacerbate urban-rural and North-South inequality in the country (Polaski 2004). Such inequalities further stimulated internal and international migration (Lozano-Ascencio, Robert, and Bean 1999). Informed by these broader trends, we include both state and year fixed effects in the models presented below to control for space-varying-time-fixed and space-fixed-time-varying unobserved characteristics respectively.

Key to examination of a potential migration-environment connection within Mexico are ejidos -- rural communities which collectively possess rights to land and whose resident members (ejidatarios) are entitled to work a plot of their own (Wiggins et al. 2002). Ejidos, created through land transfers starting in the 1930s, contain approximately 60% of the rural population (de Janvry and Sadoulet 2001). Market liberalization during the 1990s allowed ejidatarios to attain individual titles and therefore enable sale of their lands, although very few have sold (Barnes 2009).

Ejido residents are even more dependent on natural capital than the rural households described by Wiggins et al. (2002). In Winters, Davis and Corral’s (2002) examination of a nationally representative sample of Mexican ejido households, fully 93.7% participated in crop production while agricultural activities as a whole (crops, livestock and agricultural employment) comprised over half (55%) of total rural ejido household income. De Janvry and Sadoulet (2001) further document that agricultural contributions to ejidatario household income range from 23 to 67% depending on landholding size.

Recent work suggests that contemporary efforts to provide ejido households with a certificate of land ownership are associated with an increase in U.S. emigration, inferring that more secure access to such natural capital provides a foundation from which to engage in the relatively-expensive livelihood diversification strategy of international migration (Valsecchi 2010). As such, our modeling strategy includes type of land ownership at the household scale.

Yet other forces clearly shape livelihood strategies. Winters and colleagues (2002:141) note that livelihood decision-making “is conditioned on the context in which the household operates – influenced through natural forces, markets, state activity and societal institutions”, which may shape access to water resources (e.g., irrigation systems). In this way, environmental change acts in concert with political-economic forces to shape livelihood strategies. As such we turn now to reviewing the history and political economy of Mexico-U.S. migration.

Mexico-U.S. Migration

Mexican migration to the U.S. has a long history. Sustained, massive movement of labor migrants dates back to recruitment efforts by U.S. employers in the early 20th century (Cardoso 1980; Foerster 1925). Migration streams plummeted during the Great Depression (Balderrama and Rodriguez 2006) but emerged again in 1942 due to a bi-national labor accord with Mexico, the Bracero Program (Calavita 1992). The Bracero Program survived its original purpose of providing emergency farm labor but was discontinued in 1964 as part of broader civil rights and immigration reform. Despite the end of the program, immigration from Mexico continued, both legally and undocumented, in a somewhat circular fashion (Cornelius 1992; Massey et al. 2002). Considerable increases in migration streams occurred in the 1990s and for part of the first decade of the 21st century (Passel and Cohn 2011; Warren and Warren 2013) as Mexican emigration increased (Bean et al. 2001) and short-term return migration rates plummeted (Massey et al. 2002; Riosmena 2004). Yet recent estimates suggest that unauthorized immigration to the U.S. has declined substantially since 2008 (Warren and Warren 2013), that net immigration from Mexico has reached a standstill and that the Mexican-born population in the U.S. has actually declined in recent years. (Passel et al. 2012). Even so, migration networks remain strong and it remains to be seen if Mexico-U.S. flows will again rise in better economic times and with climate pressures on agricultural livelihoods in origin communities.

Historically, much of the Mexico-U.S. migration flows have come from rural areas in Central-Western Mexico. The geography of these migration flows was associated with the location of the main railroad lines (Cardoso 1980) coupled with low population levels in the border region. Through the years, these flows perpetuated and gained strength (Durand et al. 2001; Durand and Massey 2003). Key to the present analyses, this regional concentration relates to the buildup of strong translocal connections between sending and destination communities (Massey et al. 1987). Social capital in the form of migration networks can decrease costs associated with migration by providing information and assistance that lessen the risks and expenses associated with border-crossing and unemployment upon arrival. In fact, having familial and community-wide connections with migrants in the U.S. is one of the best predictors of U.S.-bound migration from Mexico (Massey and Espinosa 1997; Phillips and Massey 2000; Massey and Riosmena 2010), particularly from rural areas (Fussell and Massey 2004; Massey et al. 1994). Therefore, migrant networks help perpetuate emigration in communities once they reach substantial levels (Lindstrom and Lopez-Ramirez 2010; McKenzie and Rapoport, 2007).

Although migration networks have traditionally been concentrated in the Central-Western region, a nontrivial portion of migrants has always, and increasingly, come from less traditional sending regions South and East of Mexico City (e.g., Durand and Massey 2003; Cornelius 2009). As these areas are disproportionately rural, the particular speed of this social network build-up and diffusion over rural communities in less traditional sending regions may in turn be associated with the deep restructuring of the Mexican countryside over the last two decades (Nevins 2007; Riosmena and Massey 2012). For this reason we conduct our analyses separately on regions with high historical sending rates as compared to other regions without these deeper historical ties.

Additionally, an individual’s prior experience is strongly associated with the likelihood of subsequent migration as it is argued that the relevance of migration-specific social capital diminishes as individuals acquire their own migration-specific human capital (Massey and Espinosa 1997). In addition to controlling for this prior U.S. experience, we examine if rainfall variability is associated with migration in similar ways according to the prior U.S. migration experience of household members.

Data

We use data from the Mexican Migration Project, a bi-national research initiative based at Princeton University and the University of Guadalajara. Since 1987, the MMP has annually selected between 4 and 6 Mexican communities and interviews a random sample of approximately 200 households in each community. Given the focus on rural livelihoods, our sample is restricted to non-urban communities, defined traditionally in Mexico as those with less than 2,500 inhabitants. Since we include state-level rainfall data and in order to ensure representation and variation in state-level variables over time, only states in which more than one community has been surveyed are included (see Appendix A). This also allows for inclusion of state fixed effects in our regression specification (see Munshi 2003). With this restriction, our working sample includes 23,686 households in 66 communities located in 12 states surveyed from the year of 1987 to 2005.

Since migration has consistently varied by region within Mexico, and given the strength of Mexican migration’s association with existing migrant networks, we disaggregated the data into two key categories. Communities located in the "historical region" represent central-western states that have historically contributed most of the emigrant flow (Durand and Massey 2003). In our data, 74% of households are located within this region, namely in the states of Zacatecas, Guanajuato, Jalisco, Michoacán, San Luis Potosí, Aguascalientes, and Colima. The remainder set of communities comprises “all other regions” located in the states of Chihuahua in the border region; Puebla, Guerrero, and Oaxaca in the central region; and Veracruz in the southeast (for a full regional classification, see Durand and Massey 2003).

The MMP questionnaire collects basic socio-demographic and retrospective migration questions about all members of the household at the time of survey. Data are also collected on all children of the household head regardless of their place of residence. Among these questions, respondents report the dates and duration (if applicable) of the first and last U.S. trip for all people listed in the household roster. Our dependent variable reflects emigration to the U.S. by any individual age 15+ in the household roster within three years prior to the survey (that is, during the survey year and two years prior). U.S.-bound migration is a relatively common phenomenon among the MMP respondents, with approximately 21% of households sending a migrant to the U.S. during the three-year window. As expected, there are large differences between the emigration rates from historical and other sending communities in our sample: whereas 25% of households in the historical region sent a migrant to the United States in the 3-year window of observation, only 11% of households in other regions did so (see Table 1).2

Table 1.

Means (and Standard Deviations) of Dependent Variable and Covariates in the Analysis

| All communities | Historical Region | All Other Regions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (S.D.) | Mean | (S.D.) | Mean | (S.D.) | |

| Outcome of interest | ||||||

| Proportion households sending a migrant | 0.206 | (0.404) | 0.245 | (0.430) | 0.106 | (0.308) |

| State-level climatic variability (natural capital shifts) | ||||||

| Current year a drought year | 0.179 | (0.384) | 0.207 | (0.405) | 0.100 | (0.300) |

| Current year is a Severe drought year | 0.058 | (0.235) | 0.016 | (0.127) | 0.181 | (0.385) |

| Last year a drought year | 0.316 | (0.465) | 0.384 | (0.486) | 0.120 | (0.325) |

| Last year was a severe drought year | 0.067 | (0.251) | 0.032 | (0.176) | 0.170 | (0.375) |

| Two years ago was a drought year | 0.301 | (0.459) | 0.384 | (0.486) | 0.062 | (0.242) |

| Two years ago was a Severe drought year | 0.058 | (0.234) | 0.033 | (0.180) | 0.130 | (0.336) |

| Current year a wet year | 0.175 | (0.380) | 0.145 | (0.352) | 0.261 | (0.439) |

| Current year is a severe wet year | 0.110 | (0.313) | 0.125 | (0.331) | 0.067 | (0.250) |

| Last year was a wet year | 0.132 | (0.338) | 0.136 | (0.343) | 0.120 | (0.325) |

| Last year was a severe wet year | 0.105 | (0.306) | 0.079 | (0.269) | 0.181 | (0.385) |

| Two years ago was a wet year | 0.098 | (0.298) | 0.111 | (0.314) | 0.062 | (0.242) |

| Two years ago was a severe wet year | 0.100 | (0.300) | 0.035 | (0.183) | 0.287 | (0.452) |

| Household's human capital | ||||||

| No. of household members | 4.9 | (2.4) | 5.0 | (2.5) | 4.6 | (2.1) |

| Proportion of household in labor force | 0.397 | (0.234) | 0.397 | (0.236) | 0.394 | (0.225) |

| Proportion of household that is daughters | 0.234 | (0.195) | 0.240 | (0.196) | 0.215 | (0.192) |

| Household head is employed | 0.855 | (0.352) | 0.851 | (0.356) | 0.864 | (0.343) |

| Age of household head | 47.675 | (15.632) | 47.473 | (15.889) | 47.998 | (14.903) |

| Schooling years, household head | 5.0 | (4.4) | 4.9 | (4.4) | 5.6 | (4.3) |

| Age of spouse (if applicable) | 35.3 | (20.0) | 35.2 | (19.9) | 35.7 | (20.1) |

| Schooling years, spouse (if applicable) | 4.2 | (3.9) | 4.1 | (3.9) | 4.5 | (4.0) |

| Household's financial and physical capital | ||||||

| Household engaged in farming | 0.263 | (0.440) | 0.215 | (0.411) | 0.316 | (0.465) |

| Household owns a business | 0.221 | (0.415) | 0.215 | (0.411) | 0.231 | (0.422) |

| Household has both a farm and business | 0.062 | (0.241) | 0.048 | (0.215) | 0.093 | (0.291) |

| Primary property is in community/ejido land | 0.157 | (0.364) | 0.135 | (0.342) | 0.217 | (0.412) |

| Amenities in HH (out of 11) | 7.489 | (2.386) | 7.608 | (2.343) | 7.152 | (2.496) |

| Percent of Sample with more than Median Amenities | 0.545 | (0.498) | 0.556 | (0.497) | 0.512 | (0.499) |

| Household's migration-specific social capital | ||||||

| Percent HH head has been to US | 0.351 | (0.5) | 0.402 | (0.490) | 0.203 | (0.403) |

| Percent spouse has been to US | 0.061 | (0.240) | 0.1 | (0.3) | 0.0 | (0.2) |

| Municipal-level socioeconomic levels, community-level migration-specific social capital | ||||||

| Female labor force participation | 0.131 | (0.053) | 0.131 | (0.045) | 0.133 | (0.070) |

| Female labor force in manufacturing | 0.206 | (0.151) | 0.196 | (0.151) | 0.234 | (0.149) |

| Male labor force in agriculture | 0.500 | (0.190) | 0.465 | (0.155) | 0.585 | (0.240) |

| Community Migration Prevelance in 1980 | 0.185 | (0.152) | 0.237 | (0.144) | 0.049 | (0.050) |

| Community Migration Prevelance Lagged 1 year | 0.246 | (0.137) | 0.286 | (0.132) | 0.129 | (0.072) |

| Sample Size | 23,686 | 17,613 | 6,073 | |||

Central to this project are variables reflecting the availability of natural capital as shaped by variability in rainfall. Rainfall measurements are commonly used to reflect the consumption impacts of weather shocks (e.g., Dercon and Krishnan 2000; Skoufias et al. 2011). Our main predictor variables represent deviations from long-term average rainfall at the state level. We follow the lead of a large body of climate science and use a 30-year mean as “climate normal” for assessment of variability (NCDC 2011). We define “drought” years as those in which the state-level rainfall measurement was one standard deviation below the 30-year mean, while “severe drought” years represent two standard deviations below the 30-year mean. Inversely, we define “wet” or “severe wet” years as those with rainfall one or two standard deviations above the 30-year mean respectively.

There is substantial variation in precipitation regimes in our total sample, with an overall mean of 18% of households subjected to drought during the survey year. In addition 32% of our sample had a drought the year prior to the survey while a similar level (30%) experienced drought two years prior. As would be anticipated, severe droughts are far less frequent with only 6% of households experiencing them during the survey year, 7% the year prior, and 6% two years prior.

Fewer sample households experienced relatively high levels of rainfall, although “wet” locations are more consistently wet across time. For example, 18% of households experienced a wet year during their survey year, 13% the year prior and 10% two years prior. Similar levels characterize “severe wetness” with 11% of households experiencing rainfall at least 2 standard deviations above the 30-year normal during their survey year, 11% in the year prior and 10% two years prior.

With regard to the categorization by historical sending regions, the clearest distinctions relate to drought. Households in regions with stronger histories of sending migrants to the U.S. are more likely to have been subject to drought during the 3-year window compared to those in other sending regions (20% to 10% respectively). On the other hand, households in non-historical regions were more likely to have experienced severe drought as compared to historical region households (20% compared to 2%, respectively, for year of survey). No clear patterns emerge with regard to wetness by region.

At the household level, included variables reflect access to human capital (e.g., household composition, percent female, life cycle stages, and educational levels), financial capital (e.g., business ownership), physical capital (e.g., land and livestock ownership, possessions), and social capital (e.g., trips to U.S. prior to the 3-year measurement window, perhaps a measure of both migration-specific social and human capital). On human capital, the average household has almost 5 members with only 5% of households having no children. A large portion of households, 42%, have both young and teenage children and on average 40% of household members are in the labor force (reflecting the presence of older children). On average 23% of the family members are daughters, which is controlled for as female family members are less prone to migrate (Cerrutti and Massey 2001). Eighty-six percent of household heads are employed; heads have on average 5 years of formal schooling. Differences in human capital across regions are minimal, with households located out of the historical region being smaller (4.6 vs. 5.0 members) and having heads with slightly higher levels of schooling (4.5 vs. 4.1 years).

On financial and physical capital, about 25% of households are engaged in farming, with percentages slightly higher in non-historical sending regions compared to historical sending regions (32% vs. 22% respectively). This relates to the higher levels of ejido land as well, with 22% of households in the historical region having ejido land as their primary property, compared to only 14% in all other regions. On the other hand, business ownership occurs at the same level across regions (22% vs. 23% in the historical vs. other regions), as does ownership of a variety of physical capital (“amenities”) with the overall sample noting 7.5 out of 11 classified possessions.

On social capital, 35% of surveyed households have a head with prior U.S. migration experience. However this average is composed of a higher rate of migration in the historical regions with approximately 40% of household heads with prior US migration experience and only 20% of households in non-historical regions with experience. Fewer spouses have made the journey – overall only 6%, and virtually none within the non-historical regions (see footnote 2).

The various capitals represented by the household-level data are supplemented with information collected by the MMP at the community and municipal scales that reflect access to livelihood diversification options. For instance, prior work has shown that migration is associated with local economic conditions that are particularly indicative of opportunities for remunerated work for women (Kana'iaupuni 2000; Riosmena 2009). As such, we use female labor force participation rates and the proportion of the female labor force in manufacturing. We also measure the municipality’s dependence on agriculture in terms of the proportion of males in the labor force devoted to these activities. Finally, we include the previous year’s community-level migration prevalence to control for varying levels of community-level social capital, the strength of broader migrant networks (see Fussell and Massey 2004; Lindstrom and Lopez-Ramirez 2010).

Lending credence to our disaggregation by regions characterized by different migration histories, 24% of individuals aged 15 and over in historical sending regions had been to the United States in 1980, compared to only 4.9% in less traditional sending communities. Further, communities located outside the historical regions have higher dependence on agriculture (male participate rate 59% vs. 47%). And although the regions have nearly identical rates of female labor force participation, non-historical sending regions have slightly higher levels of female labor participation in manufacturing specifically (23% vs. 20%).

Methods

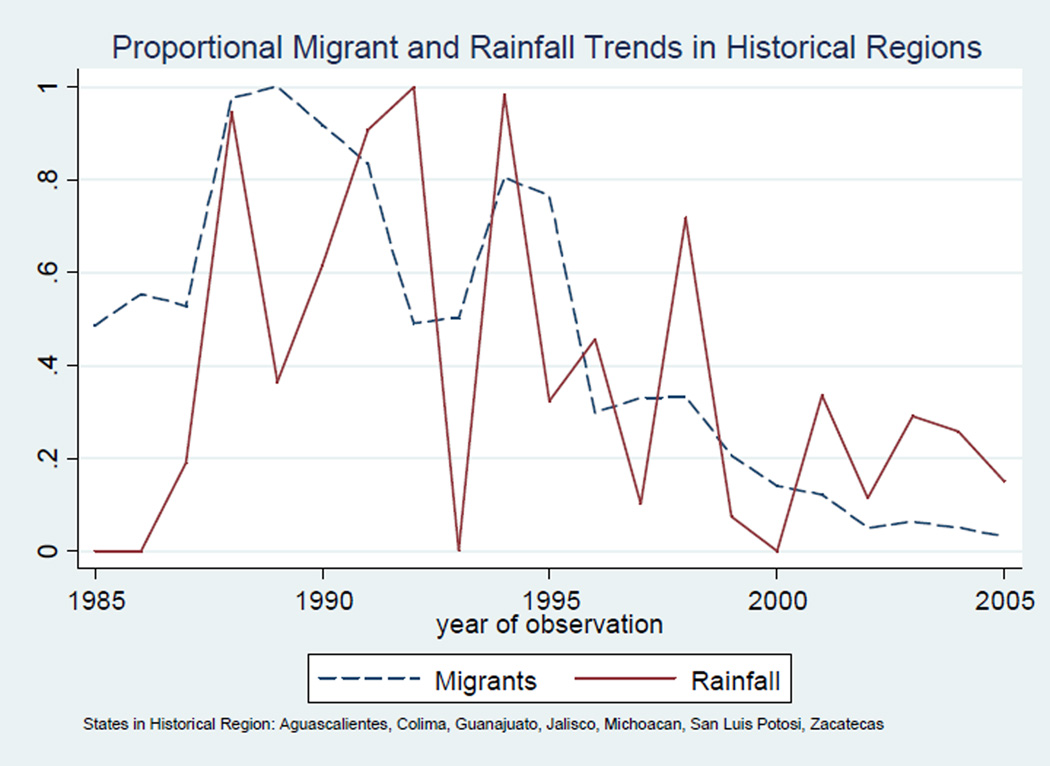

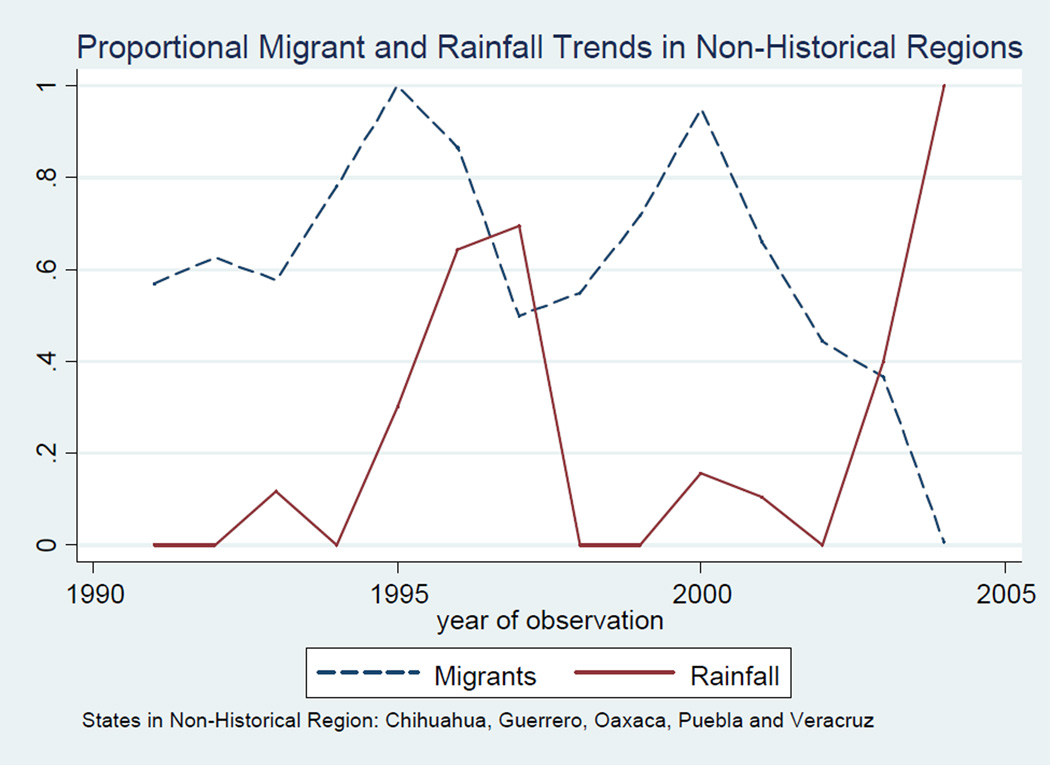

We first simply graph aggregated migration and precipitation trends across time, by state. Importantly, we present migration trends only after high levels of migration motivated by the 1986 Immigration and Reform Control Act (IRCA), which provided amnesty to approximately 2.3 million seasonal and undocumented Mexican workers in the U.S. We also present separate graphs for historical and non-historical migration-sending regions. Rainfall trends are calculated as the percentage of rain in the most recent year in comparison to maximum of the sample timeframe. Similarly, migration prevalence represents the number of adults reported in the MMP, retrospectively, as having left in each year and the trend line is formed by calculating the percentage of migration prevalence in the current year in comparison to the maximum within the overall sample timeframe.

As noted, the MMP is a repeated cross-sectional survey that includes retrospective questions. To undertake multivariate analyses, we use information from the retrospective questions to generate a pseudo-panel across a 3-year window for each household. We then estimate event history models predicting the probability of migration within a household during that 3-year period. We model migration at the household level since, in this context, such livelihood strategies represent household decision processes (e.g., Hondagneu-Sotelo 1994). We use a three-year recall window to: 1) minimize potential memory biases (Auriat 1991; Smith and Thomas 2003); 2) increase representativeness by avoiding going too far back in time, when the experience of people emigrating is lost; and 3) maximize available covariates for modeling purposes as many of the community and household characteristics are measured only in the survey year (e.g., our household amenity index; as such, we assume they remained stable during the 3-year window). Static measurements such as these clearly limit our ability to use retrospective information too far back due to obvious temporal mismatch.

Our outcome of interest is a time-dependent event which has a probability of occurrence derived from a censored distribution since the potential migration ‘window’ ends at the point of data collection. As such, we employ discrete-time event survival analysis techniques and, following Allison (1982), fit a logistic regression model on a set of pseudo-observations, in this case household-years of exposure before the first household member’s emigration (if one) during the three-year window (see also Singer and Willett 2003). To control for changing economic conditions, we use both state and year fixed effects. Finally, since data from each MMP community comes from a random sample, pooling communities in any analysis implies the clustering of households within communities. We estimate robust standard errors accordingly.

Tables 2 and 3 present three models run separately for historical and other sending regions respectively. For each region, we model the probabililty that a household member initiates a U.S. trip as a function of:

indicators of state-level rainfall at least one deviation below or above the 30-year average for the survey year, one year prior and two years prior,

indicators of state-level rainfall either one standard deviation below or two standard deviations below the 30-year average for the survey year, one year prior and two years prior. As compared to the measurement outlined in #1, distinguishing two standard deviations represents more severe drought or wet conditions;

interactions between household head prior international migration experience and the one and two standard deviation rainfall measures. These models test the relevance of migration-specific social capital as a facilitator of environmentally-associated international migration (Massey 1990).3

All models include the comprehensive suite of community- and household-level control variables described before as well as state and year fixed effects.

Table 2.

Discrete Time Logit predicting the Likelihood of Household Sending a Migrant in Historical Regions

| (I) | (II) | (III) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | |

| Community Level Capital | ||||||

| Female Labor Force Participation in 1900 between 10–20% | −0.32+ | (0.18) | −0.29+ | (0.17) | −0.28 | (0.17) |

| Female Labor Force Participation in 1990 above 20% | −0.01 | (0.25) | 0.01 | (0.23) | 0.03 | (0.22) |

| Female Labor force in manufacturing is over 50% | 0.82*** | (0.23) | 0.69*** | (0.21) | 0.69*** | (0.21) |

| Male labor force participation in Agriculture is over 50% | 0.42*** | (0.13) | 0.40 ** | (0.12) | 0.40*** | (0.12) |

| Household's human capital | ||||||

| % of HH members in labor force | 0.65*** | (0.14) | 0.64*** | (0.14) | 0.64*** | (0.14) |

| HH Head is employed | −0.19 | (0.13) | −0.18 | (0.13) | −0.18 | (0.13) |

| life Cycle - young children only | 1.25*** | (0.19) | 1.26*** | (0.19) | 1.26*** | (0.19) |

| Life Cycle - young and teenage children | 1.64*** | (0.21) | 1.65*** | (0.21) | 1.64*** | (0.21) |

| life Cycle -teenage children only | 0.65* | (0.32) | 0.63+ | (0.32) | 0.63+ | (0.32) |

| life Cycle - all children are adults | 1.51*** | (0.25) | 1.53*** | (0.25) | 1.53*** | (0.24) |

| HH head education | −0.06*** | (0.01) | −0.06*** | (0.01) | −0.06*** | (0.01) |

| HH head age | −0.01* | (0.00) | −0.01 ** | (0.00) | −0.01 ** | (0.00) |

| Spouses education | −0.05*** | (0.01) | −0.05*** | (0.01) | −0.05*** | (0.01) |

| Spouses age | −0.00 | (0.00) | −0.00 | (0.00) | −0.00 | (0.00) |

| % daughters in family | −0.61*** | (0.17) | −0.62*** | (0.17) | −0.63*** | (0.17) |

| Household's financial and physical capital | ||||||

| Primary land is community or Ejido | 0.39 ** | (0.14) | 0.39 ** | (0.14) | 0.39 ** | (0.14) |

| High Amenity HH | 0.08 | (0.14) | 0.07 | (0.14) | 0.07 | (0.14) |

| Percent of ammenitites HH has out of 11 | 1.05*** | (0.28) | 1.06*** | (0.29) | 1.07*** | (0.29) |

| Number of types of live stock | 0.12*** | (0.03) | 0.13*** | (0.03) | 0.13*** | (0.03) |

| HH owns a business | −0.39*** | (0.09) | −0.39*** | (0.09) | −0.39*** | (0.09) |

| HH Engages in farming | −0.16+ | (0.09) | −0.17+ | (0.09) | −0.17+ | (0.10) |

| Household's migration-specific social capital | ||||||

| HHH has been to US prior to 3 year survey period | 0.47*** | (0.09) | 0.47*** | (0.09) | 0.54*** | (0.10) |

| Total number of US trips made by HHH prior to 3 yr survey period | 0.16*** | (0.02) | 0.16*** | (0.02) | 0.16*** | (0.02) |

| Spouse has been to US prior to 3 year survey period | 0.30+ | (0.18) | 0.29 | (0.18) | 0.29 | (0.18) |

| Migration Prevalence in Community (lagged 1 year) | 0.02*** | (0.00) | 0.01 ** | (0.00) | 0.01*** | (0.00) |

| State-level climatic variability (natural capital shifts) | ||||||

| Current year = any drought | 0.34* | (0.14) | ||||

| Last year = any drought | 0.56*** | (0.13) | ||||

| Two years ago = any drought | 0.20 | (0.19) | ||||

| Current year = any wet | −0.30* | (0.14) | ||||

| Last year = any wet | −0.29+ | (0.17) | ||||

| Two years ago = any wet | −0.17 | (0.23) | ||||

| Current year = drought | 0.19 | (0.18) | 0.28 | (0.18) | ||

| Current year = Severe drought | −2.88*** | (0.81) | −2.72 ** | (0.84) | ||

| Last year = drought | 0.42* | (0.20) | 0.40+ | (0.22) | ||

| Last year = severe drought | −2.36 ** | (0.73) | −2.28 ** | (0.78) | ||

| Two years ago = drought | −0.08 | (0.23) | −0.04 | (0.23) | ||

| Two years ago =severe drought | 2.73*** | (0.55) | 2.48*** | (0.63) | ||

| Current year = wet | 0.09 | (0.18) | 0.17 | (0.20) | ||

| Current year = severe wet | −0.56 ** | (0.19) | −0.63 ** | (0.21) | ||

| Last year = wet | 0.38 | (0.28) | 0.42 | (0.30) | ||

| Last year = severe wet | −0.56*** | (0.13) | −0.69*** | (0.15) | ||

| Two years ago=wet | 0.37 | (0.27) | 0.40 | (0.27) | ||

| Two years ago= severe wet | −1.17*** | (0.22) | −1.38*** | (0.21) | ||

| HH head has been to US & drought year | −0.18 | (0.12) | ||||

| HH head has been to US & severe drought year | −11.44*** | (1.31) | ||||

| HH head has been to US & drought last year | 0.00 | (0.10) | ||||

| HH head has been to US & severe drought last year | −11.28*** | (1.36) | ||||

| HH head has been to US & drought two years ago | −0.11 | (0.09) | ||||

| HH head has been to US & severe drought two years ago | 11.86*** | (1.39) | ||||

| HH head has been to US & wet year | −0.15 | (0.14) | ||||

| HH head has been to US & severe wet year | 0.13 | (0.15) | ||||

| HH head has been to US & wet last year | −0.06 | (0.17) | ||||

| HH head has been to US & severe wet last year | 0.20 | (0.16) | ||||

| HH head has been to US & wet two years ago | . | . | ||||

| HH head has been to US & severe wet two years ago | 0.45* | (0.23) | ||||

| Intercept | −3.77*** | (0.85) | −3.75*** | (0.79) | −3.83*** | (0.79) |

| Observations | 17,613 | 17,465 | 17,465 | |||

All regressions include state and year fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the community level.

p<0.001,

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.10

Table 3.

Discrete Time Logit predicting the Likelihood of Household Sending a Migrant in Non-Historical Regions

| (I) | (II) | (III) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | ||

| Community Level Capital | |||||||

| Female Labor Force Participation in 1900 between 10–20% | 0.40 | (0.30) | 0.40 | (0.30) | 0.40 | (0.30) | |

| Female Labor Force Participation in 1990 above 20% | −2.09*** | (0.51) | −2.09*** | (0.51) | −2.09*** | (0.50) | |

| Female Labor force in manufacturing is over 50% | −1.41** | (0.49) | −1.41** | (0.49) | −1.38** | (0.51) | |

| Male labor force participation in Agriculture is over 50% | −1.09*** | (0.20) | −1.09*** | (0.20) | −1.09*** | (0.20) | |

| Household's human capital | |||||||

| % of HH members in labor force | 0.35 | (0.39) | 0.35 | (0.39) | 0.33 | (0.38) | |

| HH Head is employed | −0.58* | (0.24) | −0.58* | (0.24) | −0.60* | (0.24) | |

| Life Cycle - young children only | 2.11** | (0.80) | 2.11** | (0.80) | 2.13** | (0.79) | |

| Life Cycle - young and teenage children | 2.55** | (0.78) | 2.55** | (0.78) | 2.56*** | (0.77) | |

| Life Cycle - teenage children only | 1.47 | (0.92) | 1.47 | (0.92) | 1.50 | (0.93) | |

| Life Cycle - all children are adults | 1.70* | (0.74) | 1.70* | (0.74) | 1.71* | (0.74) | |

| HH head education | −0.06*** | (0.02) | −0.06*** | (0.02) | −0.06*** | (0.02) | |

| HH head age | −0.02** | (0.01) | −0.02** | (0.01) | −0.02** | (0.01) | |

| Spouses education | −0.06* | (0.03) | −0.06* | (0.03) | −0.07* | (0.03) | |

| Spouses age | 0.00 | (0.00) | 0.00 | (0.00) | 0.00 | (0.00) | |

| % daughters in family | −0.62 | (0.43) | −0.62 | (0.43) | −0.62 | (0.43) | |

| Household's financial and physical capital | 0.29 | (0.25) | 0.29 | (0.25) | 0.28 | (0.25) | |

| Primary land is community or Ejido | 0.30 | (0.23) | 0.30 | (0.23) | 0.32 | (0.24) | |

| High Amenity HH | 1.27* | (0.60) | 1.27* | (0.60) | 1.27* | (0.61) | |

| Percent of ammenitites HH has out of 11 | −0.08 | (0.11) | −0.08 | (0.11) | −0.08 | (0.11) | |

| Number of types of livestock | −0.12 | (0.18) | −0.12 | (0.18) | −0.10 | (0.18) | |

| HH owns a business | 0.08 | (0.19) | 0.08 | (0.19) | 0.09 | (0.19) | |

| HH Engages in farming | |||||||

| Household's migration-specific social capital | |||||||

| HHH has been to US prior to 3 year survey period | −0.94* | (0.47) | −0.94* | (0.47) | −0.89 | (0.57) | |

| Total number of US trips made by HHH prior to 3 yr survey period | 0.72** | (0.24) | 0.72** | (0.24) | 0.71** | (0.25) | |

| Spouse has been to US prior to 3 year survey period | 0.75* | (0.34) | 0.75* | (0.34) | 0.77* | (0.33) | |

| Migration Prevalence in Community (lagged 1 year) | 0.10*** | (0.03) | 0.10*** | (0.03) | 0.10*** | (0.03) | |

| State-level climatic variability (natural capital shifts) | |||||||

| Current year = any drought | −3.38*** | (0.22) | |||||

| Last year = any drought | −0.37+ | (0.22) | |||||

| Two years ago = any drought | 0.18 | (0.47) | |||||

| Current year = any wet | 0.24 | (0.35) | |||||

| Last year = any wet | 1.08** | (0.35) | |||||

| Two years ago = any wet | 0.63* | (0.29) | |||||

| Current year = drought | −1.94*** | (0.38) | −1.62*** | (0.35) | |||

| Current year = Severe drought | −0.51*** | (0.06) | −0.52*** | (0.13) | |||

| Last year = drought | −0.49 | (0.47) | −0.72+ | (0.40) | |||

| Last year = severe drought | −0.51*** | (0.06) | −0.52*** | (0.13) | |||

| Two years ago = drought | −1.84*** | (0.55) | −1.86*** | (0.46) | |||

| Two years ago =severe drought | 0.41 | (0.36) | 0.10 | (0.35) | |||

| Current year = wet | −1.04*** | (0.26) | −1.11*** | (0.22) | |||

| Current year = severe wet | 0.24 | (0.35) | 0.27 | (0.33) | |||

| Last year = wet | . | . | . | . | |||

| Last year = severe wet | −0.20 | (0.27) | −0.24 | (0.22) | |||

| Two years ago=wet | . | . | . | . | |||

| Two years ago= severe wet | −0.91 | (0.64) | −0.86 | (0.66) | |||

| HH head has been to US & drought year | −0.56 | (0.34) | |||||

| HH head has been to US & severe drought year | 0.04 | (0.32) | |||||

| HH head has been to US & drought last year | 0.05 | (0.29) | |||||

| HH head has been to US & severe drought last year | 0.61* | (0.26) | |||||

| HH head has been to US & drought two years ago | −0.61 | (0.42) | |||||

| HH head has been to US & severe drought two years ago | 0.51 | (0.39) | |||||

| HH head has been to US & wet year | −0.24 | (0.21) | |||||

| HH head has been to US & severe wet year | −0.12 | (0.40) | |||||

| HH head has been to US & wet last year | . | . | |||||

| HH head has been to US & severe wet last year | −0.42+ | (0.24) | |||||

| HH head has been to US & wet two years ago | . | . | |||||

| HH head has been to US & severe wet two years ago | 0.16 | (0.31) | |||||

| Intercept | |||||||

| Observations | 6,073 | 6,073 | 6,073 | ||||

All regressions include state and year fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the community level.

p<0.001,

p<0. 01,

p<0. 05,

p<0.10

Results

First, Figures 1 and 2 present trend lines for sampled Mexican communities in regions with strong historical migration streams and those without. The figures hint at a negative association between rainfall patterns and emigration. For example, in historical regions (Figure 1), the relatively dry year of 1989 was associated with relatively high levels of outmigration from study communities although these increases could be due to other factors, such as family reunification in the aftermath of IRCA. Still, migration declined following increases in rain during the early 1990s, with a consistent decline after a peak rainfall year in 1994 despite the fact that Mexico then underwent one of its most severe economic crises in recent memory; Relative migration again increases during a period of low rainfall around the year 2000.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Historical sending regions

Table 2 presents results of the first set of discrete-time event history models focused on historical sending regions. Many of the standard migration predictors behave similarly across models. For example, human capital variables suggest households with more educated heads are less likely to send an international migrant, perhaps since they face more favorable local diversification opportunities. Spouse’s education and household’s business ownership are associated with lower emigration probabilities, again likely due to existing diversification strategies (Massey and Espinosa 1997; Riosmena 2009).

Ejido or communal land ownership are associated with a higher probability of migration (as posited by Valsecchi 2010), suggesting migration may be a more important livelihood diversification strategy under these land tenure systems. Likewise, human and social capital gained by the household head through prior migration is indeed associated with a higher likelihood of emigration. Additionally, a higher index of household amenities is associated with a higher likelihood of international migration. This association may be from higher income households being able to afford migration, or from the fact that previous migration trips have facilitated savings and amenities for the household.

Our key analytical focus, the inclusion of rainfall variability yields findings mostly in line with the “environmental scarcity” hypothesis while suggesting intriguing differences according to the degree of rainfall variability. In Model I of Table 2, drought during the household-year under analysis (defined as >1 S.D. below the long-term precipitation mean) is associated with 100 · [exp{0.34} – 1] = 40% higher odds of U.S. emigration among historical region households. Further, a drought in the year prior is associated with 100 · [exp{0.56} – 1] = 75% higher odds of U.S. migration. On the other hand, a current wet year is associated with 35% lower odds of international migration. A high rainfall year during the year prior to survey also exhibits a negative impact on the likelihood of emigration out of household located in the historical region.

Yet, disaggregating the rainfall measures into indicators of “severe” drought or wetness -- at least 2 S.D. above/below long-term mean – sheds light on the important effect of more extreme conditions. Indeed, it is these more extreme conditions that appear to primarily drive the rainfall effects. Although a lesser drought in the year prior to survey retains the positive “push” for emigration, the more severe drought measures in the year of the survey, and the prior year, exhibit dampening effects on emigration probabilities. In other words, households in regions with recent severe rainfall shortages are less likely to have sent a migrant to the U.S. Yet, with the severe drought in the more distant past – 2 years ago – the “push” of rainfall deficit is again exhibited through a positive coefficient.

As to rainfall excess, none of the measures reflecting rainfall 1 S.D. above the long-term mean achieve statistical significance. On the other hand, all three measures for “severe” wetness exhibit an association with emigration – in each case, the survey year, prior year and 2 years prior, all lessen the likelihood of emigration. The largest such effect is exhibited by households experiencing a particularly wet year 2 years prior to the survey, reducing the odds of emigration by 69 percent.

The interactions in Table 2, Model III allow for examination of differential rainfall effects on households according to the household head’s prior migration experience. Again we find statistically significant associations only with the measures of severe conditions, notably rainfall deficit. In households where the head has prior migration experience, the effect of severe drought in the survey year and year prior is strongly negative – a lessening of the likelihood of emigration. Yet, a severe drought two years prior acts as an emigration “push.”

Non-historical sending regions

Substantially different associations emerge, however, for less traditional sending areas as shown in Table 3. Within these regions, drought in the current/prior year is associated with a decrease in the likelihood of U.S.-bound migration. Specifically, drought in the concurrent year reduced the odds of U.S.-bound emigration by a substantial 97 percent. A drought the year prior was associated with a more modest reduction of 31% in international migration odds. The opposite emerges for wet years in which a year with rainfall in excess of 1 S.D. above the long-term mean is associated with increased odds of U.S.-bound migration, while a wet year 2 years prior also enhances emigration’s potential.

Again disaggregating “severe” rainfall variation adds nuance, shifting the story predominantly for households experiencing rainfall excess. In Table 3, Model II, drought measures (both 1 and 2 S.D.) continue to exhibit negative associations with emigration – suggesting scarcity dampens migration. Yet, a relatively wet year during the survey year also dampens emigration, while the lagged and extreme measures of excess rainfall do not achieve statistical significance.

On the interactions between rainfall variables and household head’s prior migration experience (Table 3, Model III), we find only one statistically significant association – a drought last year increases the likelihood of emigration but to virtually the same extent as the main effect suggests a reduction. As such, the negative effect of drought on households in general does not occur within households with prior head emigration experience. That said, the negative effect associated with rainfall excess does, indeed, occur for household with prior head emigration experience.

Discussion and Conclusions

Human migration is a complex social process contingent on origin- and destination-based factors of which climate variability may be an important one. As suggested by prior work in contexts as varied as Mali, Ethiopia, Nepal and Burkina Faso on internal movement (e.g.., Findley 1994; Henry et al. 2004; Meze-Hausken 2000), the results presented here reveal intriguing associations between rainfall patterns and U.S.-bound migration from rural Mexican households. Specifically, the results yield four key narratives. First, although droughts may increase the overall (mediumrun) likelihood of U.S.-bound migration in households in the historical region, migration may not be a likely immediate response to drought but rather one requiring some time for households to mobilize financial and social capital. Severe drought seems to constrain migration in the very short run (i.e., the same year the drought occurs), perhaps acting as a livelihood shock. However, roughly two years after severe rainfall deficits take place, emigration probabilities rise considerably. While two years could seem like a long lag to link drought and migration, we lack information on the exact timing of migration during a year; as such it is possible that migration takes place early enough in the second calendar year after a bad harvest (for maize, for instance, taking place well into the Fall; see Smeal and Zhang 1994) that the lag could represent a difference of slightly more than one full harvest season.

Second, in the historical region, excess rainfall appears to keep migrants home. This suggests that years of greater potential for productivity require less livelihood migration – more natural capital negating the need to tap into social capital. Altogether, these results suggest households are particularly prone to tap into migrant networks – social capital – in the face of declining natural capital due to rainfall shortage and in line with a long tradition of work demonstrating the ways in which social capital decreases the costs associated with international migration (Massey and Riosmena 2010), particularly from rural areas (Fussell and Massey 2004).

Third, in non-historical regions, which lack stronger migrant networks, rainfall deficits may actually constrain emigration more generally and not only in the very short term as in the historical region. In these places, emigration may entail greater costs and risks due to lower existing social capital associated with migrant networks. In this case, rainfall shortages may lessen livelihood security and options, thereby reducing the potential for an additional risky household investment in international migration. However, as households outside of the historical region where the head has U.S. migration experience prior to the retrospective window do not experience the negative effects of drought on migration, individual experience and migration-specific familial social capital do seem to enable movement by loosening the type of constraints that keep people in place during a drought.

Lastly, and also consistent with the idea that lower crop yields and crop failure may constrain the migration of households in non-historical regions, we find that rainfall excess actually spurs migration. This association aligns with that of the “environmental capital” hypothesis as illustrated, for example, in rural Ecuador, where (productive) land provides capital that can facilitate migration (Gray 2010). In rural Mexico, this association appears particularly strong in regions lacking existing social networks, perhaps as particularly good rainfall (and thus, crop yields) ease budget constraints that do not allow individuals living in places with less established migrant networks to otherwise emigrate.

Although our estimates of the effect of rainfall controlling for the community prevalence ratio should be net of differences across communities in the size of migrant networks (and, in theory, of network size between regions), note that we still find large differences in both emigration probabilities and the effect of networks on migration between the historical and other regions in an all-region “global” model (results not shown but available upon request). In this sense, the prevalence ratio, generally regarded as a measure of broader migrant networks available to people in a community, may not necessarily measure all long-term U.S.-bound movement due to differences in attrition prior to the survey date (e.g., due to the combined effects of mortality and more permanent internal and international outmigration) between people with and without prior U.S. experience (see Massey, Goldring, and Durand 1994: 1507–1508). In addition, the actual effectiveness of networks (e.g., the social capital carried in them) could vary systematically between regions. Part of this effectiveness during times of environmental stress in particular could be related to spatial heterogeneity in the livelihood and adaptation strategy portfolio available to households. As our research only included indicators of current physical and financial capital (and not of past or potential entitlements), future research should consider if broader measures of adaptive capacity may explain inter-regional/spatial differences in the association between climatic variability and migration.

Current climate models for Latin America project mean warming from 1 to 6° C, and a net increase in persons experiencing water stress (IPCC 2007). Specific to Mexico’s most valuable agricultural export, coffee, Gay et al. (2006) project climate change may yield a 34% reduction in production in Veracruz, potentially making coffee no longer an economically viable livelihood strategy (see also Nevins 2007). Clearly environmental change holds important potential to impact rural Mexicans’ livelihood strategies (Conde et al. 2006; Endfield 2007), including U.S. migration (e.g., Feng et al. 2010). Even so, the results of our study also warn against interpretations of the potential rise of climate-induced, U.S.-bound migration that do not consider not only the availability of other livelihood and adaptation strategies, but also differences in the buildup of migration-specific social capital. For instance, coffee production is mostly concentrated in Southeastern Mexico (Nevins 2007), which is not a region with a long history of migration (though it is indeed growing in tradition; see Rosas 2008). As such, the aforementioned reductions in yield may or may not increase U.S. migration substantially but could in fact be associated with a net reduction in international migrants.

While we do not claim that the future will look like the past reflected in our analyses, we do argue that the future development of the association between climate change (in terms of climate variability) and migration will likely be highly contingent on the development of migrant networks along with labor demand in different sectors in the United States, which help shape the amounts and forms of social capital carried by network nodes and distributed over networks. As such, the evolution of migration trends will likely be instrumental in shaping whether people use U.S. migration as an adaptation strategy in response to economic and social vulnerability driven by climate stress, and how these associations may vary across the Mexican territory in the future. As such, estimates of future (“climate-induced”) migrants should explicitly allow for the buildup of migrant networks (for instance, see Massey and Zenteno 1999), while understanding how standard network measures such as the prevalence ratio may have different meanings across places (e.g., Fussell and Massey 2004).

Research should also aim to understand if migration associated with climate variability is more likely to be used as a temporary adaptation strategy as compared to migration stemming from other motivations. This knowledge has different implications regarding life and development in sending areas and thus for agricultural and social policy. Further, it can hold different implications in terms of immigration and agrarian policy in destinations. Yet to get at this nuance requires more precise research approaches.

On future research, to disentangle distinctions between climate-related and other migration, information on motivations is required as well as detailed migration histories (i.e., dates, destinations, return intentions). These data may best be collected through qualitative approaches such as in-depth interviews or ethnographies within migrant-sending communities. Indeed, data collection in origin communities would aid in understanding migration’s implications for those left behind. Further, both quantitative and qualitative data revealing the gender dimensions of environmentally-related migration would allow insight as to the potential for environmental change to differentially shape the migration of men and women. Finally, a comparison of destination choices (e.g., internal and international migration) would shed light on particular household livelihood strategies. On the environmental dimension, integration of additional aspects of environmental change and vulnerability including potential for disaster impacts, and the influence of temperature fluctuations and shifts in vegetation coverage would represent logical extensions.

Regardless, the work presented here offers important insight on an important and real factor influencing migration decisions, environmental factors of particular relevance to resource-dependent rural communities. We argue such factors are too often ignored in demographic scholarship. Indeed, the public and policy realms are paying increasing attention to the potential for environmental change to alter patterns of human migration, and academic research along these lines is increasingly emerging (see Adamo and Izazola 2010). With regard to Mexico, the barrage of political pressure in the U.S. to deal with immigration might benefit from shifting focus to origin areas where social, political, economic and environmental pressures converge to shape household-decision making. In rural regions with well-established U.S. migrant networks, the present study suggests drought may enhance the likelihood of households tapping into migration’s livelihood potential. The work also suggests important constraints to migration as a coping strategy in the face of environmental pressures may be felt by households lacking migration-related social networks. Certainly such evidence suggests the environmental dimensions of livelihood strategies, including emigration, deserve additional, focused research attention.

Acknowledgements

Preliminary support for this project provided by the Center for Environment and Population (CEP) through their Summer Fellowship Program. An earlier version of this research was presented at the 2011 Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America in Washington DC. The work has also benefited from the NICHD-funded University of Colorado Population Center (grant R21 HD51146) for research, administrative, and computing support. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of CEP, NIH, or NICHD.

Appendix

Appendix Table A1.

Percentage and Standard Deviations of Climate Covariates

| Entire Sample | Historical Region | Non Historical Region | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | Std. Dev | Mean | Std. Dev | Mean | Std. Dev |

| Warm Humid | 48.54% | 0.500 | 39.79% | 0.490 | 70.11% | 0.458 |

| Mild Humid | 2.27% | 0.149 | 0.00% | 0.000 | 9.04% | 0.287 |

| Mild Dry | 49.19% | 0.500 | 60.21% | 0.489 | 20.85% | 0.406 |

| States in Sample in Historical Region | ||

|---|---|---|

| Observations | % sample | |

| Aguascalientes | 650 | 3.69% |

| Colima | 1027 | 5.38% |

| Guanajuato | 4181 | 23.74% |

| Jalisco | 3613 | 20.51% |

| Michoacan | 2369 | 13.45% |

| San Luis Potosi | 3176 | 18.03% |

| Zacatecas | 2597 | 14.74% |

Appendix Table A2.

Regressions of Primary Dependency Interactions for Historical & Non-Historical Regions

| Historical Regions | Non-Historical Regions | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (I) | (II) | (I) | (II) | |||||

| β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | |

| Community Level Capital | ||||||||

| Female Labor Force Participation in 1900 between 10–20% | −0.37+ | (0.19) | −0.38* | (0.19) | 0.42 | (0.31) | 0.44 | (0.31) |

| Female Labor Force Participation in 1990 above 20% | −0.09 | (0.25) | −0.09 | (0.24) | −2.06*** | (0.49) | −2.14*** | (0.49) |

| Female Labor force in manufacturing is over 50% | 0.82*** | (0.24) | 0.83*** | (0.24) | −1.44** | (0.48) | −1.32** | (0.50) |

| Male labor force participation in Agriculture is over 50% | 0.38** | (0.13) | 0.37** | (0.13) | −1.05*** | (0.18) | −1.16*** | (0.15) |

| Household's human capital | ||||||||

| % of HH members in labor force | 0.64*** | (0.14) | 0.64*** | (0.14) | 0.32 | (0.39) | 0.33 | (0.39) |

| HH Head is employed | −0.18 | (0.13) | −0.18 | (0.13) | −0.55* | (0.24) | −0.56* | (0.24) |

| Life Cycle - young children only | 1.30*** | (0.20) | 1.29*** | (0.20) | 2.10** | (0.79) | 2.12** | (0.81) |

| Life Cycle - young and teenage children | 1.68*** | (0.21) | 1.68*** | (0.21) | 2.54*** | (0.76) | 2.57** | (0.78) |

| Life Cycle - teenage children only | 0.74* | (0.30) | 0.74* | (0.30) | 1.46 | (0.91) | 1.48 | (0.93) |

| Life Cycle - all children are adults | 1.52*** | (0.24) | 1.52*** | (0.24) | 1.67* | (0.74) | 1.71* | (0.75) |

| HH head education | −0.06*** | (0.01) | −0.06*** | (0.01) | −0.07*** | (0.02) | −0.06*** | (0.02) |

| HH head age | −0.01* | (0.00) | −0.01* | (0.00) | −0.02** | (0.01) | −0.02** | (0.01) |

| Spouses education | −0.06*** | (0.01) | −0.06*** | (0.01) | −0.07* | (0.03) | −0.07* | (0.03) |

| Spouses age | −0.00 | (0.00) | −0.00 | (0.00) | 0.01 | (0.00) | 0.00 | (0.00) |

| % daughters in family | −0.62*** | (0.18) | −0.63*** | (0.18) | −0.63 | (0.43) | −0.65 | (0.43) |

| Household's financial and physical capital | ||||||||

| Primary land is community or Ejido | 0.38** | (0.12) | 0.37** | (0.12) | 0.34 | (0.22) | 0.32 | (0.23) |

| High Amenity HH | 0.09 | (0.14) | 0.09 | (0.14) | 0.33 | (0.23) | 0.32 | (0.23) |

| Percent of ammenitites HH has out of 11 | 1.01*** | (0.28) | 1.01*** | (0.28) | 1.13+ | (0.63) | 1.14+ | (0.64) |

| HH owns a business | −0.38*** | (0.09) | −0.38*** | (0.09) | −0.14 | (0.18) | −0.14 | (0.17) |

| HHH works in agriculture, HH owns Livestock or HH engages in farming | 0.07 | (0.10) | 0.22+ | (0.13) | −0.15 | (0.15) | −0.44+ | (0.25) |

| Households migration-specific social capital | ||||||||

| HHH has been to US prior to 3 year survey period | 0.45*** | (0.08) | 0.45*** | (0.08) | −0.88+ | (0.49) | −0.86+ | (0.50) |

| Total number of US trips made by HHH prior to 3 year survey per | 0.16*** | (0.02) | 0.16*** | (0.02) | 0.70** | (0.25) | 0.71** | (0.24) |

| Spouse has been to US prior to 3 year survey period | 0.29 | (0.18) | 0.29 | (0.18) | 0.70* | (0.33) | 0.68* | (0.34) |

| Migration Prevalence in Community (lagged 1 year) | 0.02*** | (0.00) | 0.02*** | (0.00) | 0.10*** | (0.03) | 0.10*** | (0.03) |

| Migration Prevalence in Community (lagged 1 year) | ||||||||

| Current year = any drought | 0.37* | (0.14) | 0.50** | (0.15) | −3.21*** | (0.21) | −3.20*** | (0.26) |

| Last year = Any drought | 0.57*** | (0.13) | 0.64*** | (0.15) | −0.43+ | (0.22) | −0.36+ | (0.21) |

| Two years ago = Any drought | 0.20 | (0.19) | 0.21 | (0.20) | 0.24 | (0.47) | −0.06 | (0.45) |

| Current year = wet year | −0.29+ | (0.15) | −0.22 | (0.15) | 0.26 | (0.35) | −0.06 | (0.45) |

| Last year = wet year | −0.29 | (0.18) | −0.32+ | (0.19) | 1.09** | (0.35) | 0.75 | (0.48) |

| two years ago = wet year | −0.16 | (0.23) | −0.11 | (0.23) | 0.64* | (0.29) | 0.63 | (0.39) |

| HH has primary dependency & drought year | −0.22+ | (0.13) | −0.00 | (0.29) | ||||

| HH has primary dependency & drought last year | −0.13 | (0.10) | −0.11 | (0.13) | ||||

| HH has primary dependency & drought two years ago | −0.01 | (0.14) | 0.36 | (0.31) | ||||

| HH has primary dependency & wet year | −0.13 | (0.11) | 0.39 | (0.37) | ||||

| HH has primary dependency & wet last year | 0.06 | (0.13) | 0.42 | (0.33) | ||||

| HH has primary dependency & wet two years ago | −0.11 | (0.13) | 0.03 | (0.42) | ||||

| Intercept | −3.71*** | (0.85) | −3.73*** | (0.85) | −5.05*** | (1.30) | −4.70*** | (1.30) |

| Observations | 17,811 | 17,811 | 6,097 | 6,079 | ||||

All regressions include state and year fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the community level.

p<0.001,

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.10

Footnotes

Burstein (2007) also notes that corn, in particular, continues to be a mainstay of Mexican rural livelihoods, and its production sustains some 15 million of Mexico’s 103 million residents.

The MMP data pose some limitations including, as an origin-only survey, the departure of entire households is not measured. Still, in this way, the data under-represent rural outmigration thereby potentially underestimating environmental correlates.

In addition, we estimated the models with interactions between household primary dependence on natural resource-based occupations and the measure of drought/wet at least one standard deviation below the long-term average. Due to data restrictions, this interaction cannot be estimated with consideration of separate measures of “severe” drought/wet conditions and, as such, we have included these as an Appendix.

Contributor Information

Lori M. Hunter, Department of Sociology, CU Population Center, Institute of Behavioral Science, University of Colorado at Boulder, lorimaehunter@comcast.net

Sheena Murray, Department of Economics, CU Population Center, Institute of Behavioral Science, University of Colorado at Boulder.

Fernando Riosmena, Department of Geography, CU Population Center, Institute of Behavioral Science, University of Colorado at Boulder.

REFERENCES

- Adamo SB, Izazola H. Special issue on "Human migration and the environment.". Population and Environment. 2010;32:105–108. [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Discrete-Time Methods for the Analysis of Event Histories. Sociological Methodology. 1982;13:61–98. [Google Scholar]

- Angelucci Manuela. U.S. border enforcement and the net inflow of Mexican illegal migration. Economic Development and Cultural Change. Forthcoming [Google Scholar]

- Appendini K, Liverman D. Agricultural policy, climate change, and food security in Mexico. Food Policy. 1994;19(2):149–164. [Google Scholar]

- Auriat N. Who Forgets - an Analysis of Memory Effects in a Retrospective Survey on Migration History. European Journal of Population-Revue Europenne De Demographie. 1991;7(4):311–342. doi: 10.1007/BF01796872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azam JP, Gubert F. Migrants' remittances and the household in Africa: A review of evidence. Journal of African Economies. 2006;15:426–462. [Google Scholar]

- Balderrama FE, Rodríguez R. Decade of betrayal: Mexican repatriation in the 1930s. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bardsley DK, Hugo GJ. Migration and climate change: examining thresholds of change to guide effective adaptation decision-making. Population and Environment. 2010;32:238–262. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes G. The evolution and resilience of community-based land tenure in rural Mexico. Land Use Policy. 2009;26(2):393–400. [Google Scholar]

- Bean FD, Corona R, Tuiran R, Woodrow-Lafield KA, van Hook J. Circular, Invisible, and Ambiguous Migrants: Components of Difference in Estimates of the Number of Unauthorized Mexican Migrants in the United States. Demography. 2001;38(3):411–422. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilsborrow R. Population growth, internal migration, and environmental degradation in rural areas of developing countries. European Journal of Population. 1992;8(2):124–148. doi: 10.1007/BF01797549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black R, Adger WN, Arnell NW, Dercon S, Geddes A, Thomas D. Migration and Global Environmental Change. Supplemental Issue. Global Environmental Change. 2011a;21(1):S1–S2. [Google Scholar]

- Black R, Adger WN, Arnell NW, Dercon S, Geddes A, Thomas DS. The Effect of Environmental Change on Human Migration. Global Environmental Change. 2011b;21:S3–S1. [Google Scholar]

- Burstein J. U.S.-Mexico Agricultural Trade and Rural Poverty in Mexico. Report from a Task Force Convened by the Woodrow Wilson Center’s Mexico Institute and Fundación IDEA. April 13. Washington DC: Woodrow Wilson Center; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Calavita K. The Bracero Program, Immigration, and the I.N.S. New York: Routledge; 1992. Inside the State. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso LA. Mexican emigration to the United States, 1897–1931: Socio-economic patterns. University of Arizona Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Cerrutti M, Massey DS. On the Auspices of Female Migration From Mexico to the United States. Demography. 2001;38(2):187–200. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collinson MA, Tollman SM, Kahn K, Clark SJ, Garenne M. Highly prevalent circular migration: households, mobility and economic status in rural South Africa. In: Tienda M, Findley SE, Tollman SM, Preston-Whyte E, editors. Africans on the Move: Migration in Comparative Perspective. Johannesburg, South Africa: Wits University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Conde C, Ferrer R, Orozco S. Climate change and climate variability impacts on rainfed agricultural activities and possible adaptation measures. A Mexican case study. Atmosfera. 2006;19(3):181–194. [Google Scholar]

- Conde C, Ferrer R, Gay C, Magaña V, Perez JL, Morales T, Orozco S. El Niño y la Agricultura. In: Magana V, editor. Los Impactos de El Niño en México. México: 1999. pp. 103–135. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius WA. From sojourners to settlers: The changing profile of Mexican migration to the United States. In: Bustamante JA, Reynolds CW, Hinojosa Ojeda RA, editors. U.S.-Mexico relations: Labor market interdependence. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1992. pp. 155–195. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius WA. Migration from the Mexican Mixteca: a transnational community in Oaxaca and California. San Diego: Center for US-Mexican Studies, University of California; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- De Janvry A, Sadoulet E. Income Strategies Among Rural Households in Mexico: The Role of off-farm Activities. World Development. 2001;29(3):467–80. Print. [Google Scholar]

- De Sherbinin A, VanWey LK, McSweeney K, Aggarwal R, Barbieri A, Henry S, Hunter LM, Twine W, Walker R. Rural household demographics, livelihoods and the environment. Global Environmental Change. 2008;18(1):38–53. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand J, Massey DS, Zenteno RM. Mexican immigration to the United States: Continuities and changes. Latin American Research Review. 2001;36(1):107–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand J, Massey DS. Clandestinos: Migración México-Estados Unidos en los Albores del Siglo XXI. Zacatecas: Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Eakin Hallie. Institutional Change, Climate Risk, and Rural Vulnerability: Cases from Central Mexico. World Development. 2005;33(11):1923–1938. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis F. Rural Livelihoods and Diversity in Developing Countries. Oxford UK: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Endfield GH. Archival explorations of climate variability and social vulnerability in colonial Mexico. Climatic Change. 2007;83:9–38. [Google Scholar]

- Feng S, Kruger A, Oppenheimer M. Linkages among Climate Change, Crop Yields and Mexico-US cross-border Migration. PNAS. 2010;107(32):1–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002632107. Web. 05 Aug 2010. < http://www.pnas.org/content/107/32/14257>. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng S, Oppenheimer M. Applying statistical models to the climate-migration relationships. PNAS. 2012 Oct 23;109(43):E2915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212226109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findley S. Does drought increase migration? A study of migration from rural Mali during the 1983–1985 drought. International Migration Review. 1994;28(3):749–771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foerster RF. Racial problems involved in immigration from Latin America and West Indies to U.S. Washington, D.C.: GPO; 1925. [Google Scholar]

- Fussell E, Massey DS. The limits to cumulative causation: International migration from Mexican urban areas. Demography. 2004;41(1):151–171. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gay C, Estrada F, Conde C, Eakin H, Villers L. Potential impacts of climate change on agriculture: a case study of coffee production in Veracruz, Mexico. Climate Change. 2006;79:259–288. [Google Scholar]

- Gray CL. Gender, Natural Capital, and Migration in the Southern Ecuadorian Andes. Environment and Planning. 2010;42:678–696. [Google Scholar]