Abstract

Phthalocyanines have long been used as primary donor molecules in synthetic light-powered devices due to their superior properties when compared to natural light activated molecules such as chlorophylls. Their use in biological contexts, however, has been severely restricted due to their high degree of self-association, and its attendant photoquenching, in aqueous environments. To this end we report the rational redesign of a de novo four helix bundle di-heme binding protein into a heme and Zinc(II) phthalocyanine (ZnPc) dyad in which the ZnPc is electronically and photonically isolated. The redesign required transformation of the homodimeric protein into a single chain four helix bundle and the addition of a negatively charge sulfonate ion to the ZnPc macrocycle. To explore the role of topology on ZnPc binding two constructs were made and the resulting differences in affinity can be explained by steric interference of the newly added connecting loop. Singular binding of ZnPc was verified by absorption, fluorescence, and magnetic circular dichroism spectroscopy. The engineering guidelines determined here, which enable the simple insertion of a monomeric ZnPc binding site into an artificial helical bundle, are a robust starting point for the creation of functional photoactive nanodevices.

Keywords: Magnetic circular dichroism, zinc(II) phthalocyanine, zinc(II) phthalocyanine monosulfonate, protein design

Introduction

Phthalocyanines offer a highly absorbent chromophore with excellent chemical properties, making them ideal molecules to act as primary donors in artificial light-powered devices (de la Torre et al., 2007; Rawling and McDonagh, 2007). They have been used extensively in synthetic charge separation constructs due to their chemical robustness relative to chlorophyll and porphyrin derivatives, in particular their resistance to photodecomposition. Furthermore, their ease of synthesis and their long wavelength, high molar absorptivity action spectrum, with Q-band maxima at near-infrared wavelengths of 650nm and higher, are ideal for solar energy conversion.

Phthalocyanines have seen little translation into practical application for a simple reason: even in relatively hydrophobic solvents such as chloroform, they are extremely prone to self-association, forming stacked, columnar aggregates with poor photophysical properties (Schutte et al., 1993). To take full advantage of their superior spectrochemical properties phthalocyanines must be maintained in ‘splendid isolation’, avoiding their assembly into cofacial aggregates (Brewis et al., 2000). Simple modifications such as macrocycle sulfonation, while making monomeric phthalocyanines more soluble in hydrophilic solvents, do little to inhibit the progressive accumulation of stacked phthalocyanines as the cofacial stacking interaction is highly favorable energetically. Designed proteins, which offer a unique matrix which can specifically bind phthalocyanines in isolation, promise to provide a solution to this problem. Furthermore, as the distances between donor and acceptor sites in light activated electron transfer process are critical factors in both the lifetime and yield of charge separation in proteins (Punnoose et al., 2012), it is important that we develop methods to tightly bind a ZnPc cofactor at a specified site in an artificial protein.

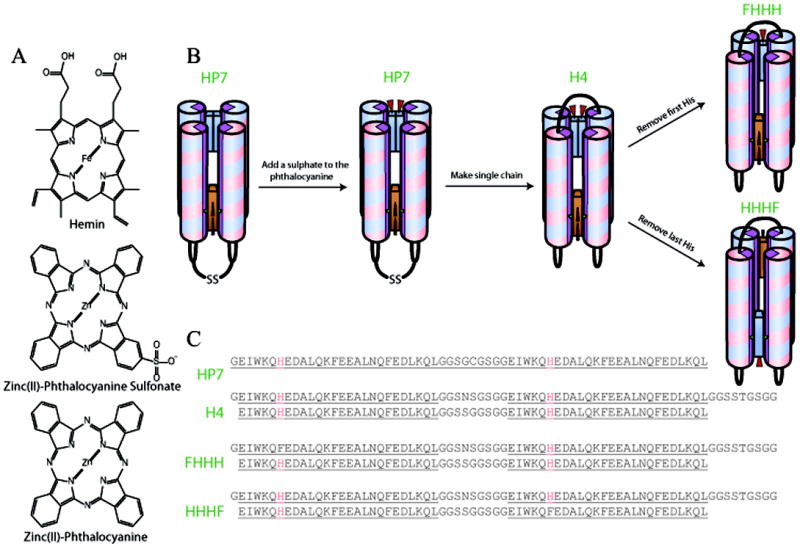

We have chosen to start with the homodimeric four α-helix bundle protein HP7, which binds two heme cofactors at two bis-histidine heme ligation sites with one histidine ligand originating from each helix (see Figure 1) (Koder et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2011a). This protein is derived from a series of progenitor proteins which started with the prototype maquette protein H10H24 (Robertson et al., 1994), a tetrameric four α-helix bundle protein and progressed through the design intermediates BB (Gibney et al., 1997) and HP-1 (Huang et al., 2004). As H10H24 has been shown to bind a wide array of porphyrins, including heme A (Gibney et al., 2000), iron mesoporphyrin IX, and iron 1-methyl-2-oxo-mesoheme XIII (Shifman et al., 2000), it seemed likely that HP7 would be able to incorporate a cofactor with a significantly different macrocyclic structure such as ZnPc (see Figure 1A). Furthermore, Noy and coworkers have recently reported that HP7 binds zinc bacteriochlorophyllide as mixed monomers and dimers at each binding site (Cohen-Ofri et al., 2011). Here we report the changes in HP7 necessary to enable the binding of an isolated ZnPc cofactor and the creation of a ZnPc-heme heterocomplex. To our knowledge, this is the first report of the creation of an artificial phthalocyanine binding protein.

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the design pathway used to make a heme phthalocyanine dyad protein, (A) Structure of the cofactors used. (B) The design pathway leading to FHHH and HHHF proteins. (C) Primary structure of each protein used in this work.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Hemin (Fluka), Zinc Phthalocyanine (ZnPc) (Aldrich) and Pyocyanine (Cayman Chemical) were purchased from the indicated companies and used without further purification. All other chemicals were from VWR, Inc. The pET32a vector containing the gene for HP7 (Koder et al., 2006) was the kind gift of P.L. Dutton. Construction of the HP7-H7F mutant was reported earlier (Zhang et al., 2011b). Molecular biology reagents were from New England Biolabs.

Synthesis of Monosulphonated Zinc Phthalocyanine (ZnPcS)

ZnPcS was synthesized using a the method of d’Allessandro et al (d’Alessandro et al., 2005) replacing the Ru(II)Cl2 with Zn(II)Cl2: Briefly, a 1:1 molar mixture of 4-sulfophthalic acid and zinc chloride with 0.1 equivalents ammonium molybdate were dissolved in water. To this mixture 3.5 mole excess of phthalic anhydride and forty parts urea were added and heated until a homogeneous solution was achieved. 1.5mL aliquots of the mixture were transferred to 20mL ampoules which were flame sealed under vacuum. The ampoules were then heated in a sand bath behind a blast shield to 200°C for 3hr then 260°C for 3.5hr.

Solid crude product was removed from the ampoules and ground to a powder, washed with brine and then extracted with ethanol. This results in a mixture of ZnPcsulfonates. Purified ZnPcS was obtained after flash chromatography using an ethyl acetate:methanol gradient from 10:0 to 9:1. ZnPcS was further purified by crystallizing from dimethylformamide/methylene chloride. Purity was confirmed by HPLC-MS using a Vydak Inc. analytical C18 column running a 5% phosphoric acid pH 5.0/methanol gradient. Yield = 2%.λabsmax (CDCl3) = 672 nm. ESIMS: m/z737.2 (M++1).

Cloning, protein expression and purification

Genes encoding HHHH (Figure 1E) were synthesized (Biomatik Corp., Cambridge, ON) with an N-terminal TEV cut site and inserted between the BamHI and XhoI restriction sites of pET32a (+) (Novagen) as previously described (Koder et al., 2006). HHHF and FHHH expression vectors were created by site directed mutagenesis using Stratagene quick change kit. All proteins, expressed from the plasmids described above as fusions with thioredoxin, were grown and purified as published previously for HP7 (Koder et al., 2006). Briefly, 2L cultures of BL21(DE3) E. coli containing the appropriate plasmid were induced at an OD600 of 1.0 with 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-thiogalactopyranoside and shaken for 5 hours at room temperature. Cells were collected by centrifugation, lysed using a French press, and proteins purified using a Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid column (Qiagen, Inc.) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The fusion protein was dialyzed into 50 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM DTT, pH 8.0 and then cleaved overnight with His6-tagged TEV protease (Invitrogen, Inc.). The reaction mixture was filtered through Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid resin, and the purified proteins concentrated by centrifugation. All stages of purification were monitored by SDS-PAGE. Pure proteins were dialyzed into either 250 mM boric acid 100 mM KCl pH 9.0 or 25 mM boric acid 10 mM KCl pH 9.5 buffers.

Spectroscopy

UV-Visible spectra were collected on either a HP8452A (Hewlett Packard, Palo Alto, CA) diode array spectrophotometer running the Olis (Bogart, GA) SpectralWorks software and equipped with a Quantum Northwest (Liberty Lake, WA) Peltier temperature controller or a Cary500 spectrometer (Varian) with a range of 200-800 nm at a scan rate of 600 nm.min-1. Fluorescence emission spectra were collected on an Olis DM45 fluorescence spectrometer. MCD spectra were measured using an 1.4 T permanent magnet (Olis) attached to a J-810 CD spectrometer (Jasco) with a range of 200-800 nm at 1 nm steps with a 1 sec response time. Spectra were averaged over four consecutive scans. The MCD spectra are corrected for CD signal. CD spectra were measured using a J-810 CD spectrometer (Jasco) as described above but in the absence of the permanent magnet. During all spectroscopy experiments the temperature was maintained at 20°C unless otherwise noted.

To determine the spectral parameters of bound ZnPcS with the heme oxidized and reduced the protein complex (10-15 μM) was degassed first under nitrogen and then using the glucose oxidase-catalase method of Berg and Abeles (Berg and Abeles, 1980). The complex was reduced using NADH and NADH-ferredoxin oxidoreductase (Smagghe et al., 2008), and absorbance and fluorescence spectra were collected.

Cofactor Binding

Protein solutions were 5-10 μM in 250 mM Borate buffer pH 9.0. Experiments were performed in 1 cm path length screw top cuvettes. Hemin solutions were approximately 1mg/mL in DMSO and exact concentrations were determined using the pyridine hemochrome method of Trumpower (Berry and Trumpower, 1987). Successive 0.1-0.2 equivalent additions of hemin were followed by a 20 minute equilibration period at 20° C. UV-Visible spectra were collected after each equilibration and binding was monitored using the bound heme Soret peak at 412 nm. Binding affinities of reduced hemin were determined in anaerobic cuvettes under reducing conditions as performed previously (Zhang et al., 2011a). Kd values were obtained from plots of the Soret band absorbance measured at 436 nm vs. the concentration of hemin added and fit with the tight binding equation:

| (1) |

Where εunb is the molar absorption coefficient of unbound hemin at that wavelength, εbnd is the additional absorbance of bound hemin at that wavelength, [hem] is the hemin concentration, [prot] is the protein concentration and Kd is the dissociation constant for the reduced hemin.

For ZnPc and ZnPcS binding, protein samples bound to a single equivalent of heme were first prepared as above. After addition of a full equivalent of heme, these samples were then passed over a PD-10 desalting column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) to remove excess DMSO. Protein-heme complex concentrations were calculated using the bound heme Soret peak at 412 nm.

ZnPc and ZnPcS binding titrations were performed by adding freshly prepared ZnPc in dimethylformamide in 0.1 equivalent quantities to1 mL aliquots of protein-heme complex at 20 minute intervals. Binding was monitored through spectral changes in the phthalocyanine Q band (630-700 nm) (Mack and Stillman, 2001; Stillman, 2000; Stillman et al., 2002). Protein-heme-ZnPcbico factor complexes were similarly prepared and purified using a PD-10 column as above.

Reduction potential determination

Reduction potential determinations were performed in combination with optical analysis as described previously (Huang et al., 2004). Concentrated solutions of hemoprotein prepared in advance were diluted to 20-30 μM into a solution containing >100 μM of the corresponding apoprotein in order to eliminate the possibility of heme dissociation upon reduction unless otherwise specified. Reported reduction potentials are referenced to a standard hydrogen electrode. All titrations were performed anaerobically using μL additions of freshly prepared sodium dithionite to adjust the solution potential to more negative values and potassium ferricyanide to more positive values. Redox titrations were analyzed by monitoring the absorbance bands at 559 and 425 nm as the heme protein was reduced or oxidized. The data were analyzed with the Nernst equation using an n-value of 1.0:

| (2) |

where %R is the fraction of reduced heme, E is the solution potential, Em is the reduction midpoint potential and n is the number of electrons.

Solution molecular weight determination

Oligomerization states were determined using size exclusion chromatography on a Biologic DuoFlow FPLC pump (Biorad Inc., Hercules, CA) equipped with a Quadtek detector and a Bioselect 125-5 300×7.6 mm column. Protein was eluted with 50 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM NaCl pH 7.5 at a 0.5 ml/min flow rate. Protein elution was monitored at 280 nm. The column was standardized as described previously (Huang et al., 2004).

Mass spectrometry

For ESI-MS a Brukermicr OTOF II ESI-TOF mass spectrometer (Bruker Billerica, MA) operated in the positive ion mode was used for all ESI-MS measurements. Samples were infused into the spectrometer at a rate of 600 μLh−1 using a microliter infusion pump. The instrument was calibrated with an external CsI standard solution. Data were processed using Bruker Data Analysis 4.0 software. Parameters: sample range = 500-4000 m/z; rolling average = 2 × 2 s; end plate offset = -500 V; nebulizer = 2.0 Bar; dry gas temp = 293 K; flow rate = 8.0 L/min; capillary voltage = 4200 V; capillary exit = 180 V; skimmer 1 = 22; hexapole = 22.50 V; hexapolerf = 600 V. The complete kinetic run was measured from a single mixture.

Results and Discussion

ZnPc binding to HP7

The homodimeric protein HP7 binds single equivalents of zinc hemin in a pentacoordinate manner using only one of the two histidine ligands available in each binding site (Koder et al., 2006). Addition of more equivalents results in the binding of an additional zinc hemin in each site in a stacked conformation wherein each zinc hemin binds one histidine. For this reason we first attempted to add substoichiometric quantities of ZnPc to HP7 which had a single heme bound, at the Histidine 42 site (Koder et al., 2009). As Figure 2 demonstrates, even at ZnPc to HP7 ratios as low as 1 to 10 the ZnPc molecules bind at this site in a stacked dimeric configuration as identified by the exciton coupled peak at 630 nm(Brewis et al., 2000). Binding was confirmed by the fact that the heterocomplex passed through a size exclusion column intact, and the retention time indicates that the heterocomplex is not oligomerized (not shown). Similar results were obtained when adding ZnPc to apoHP7 (not shown). These data make it apparent that the larger hydrophobic surface area of ZnPc drives cofactor dimerization even at very low concentrations, and the malleability of the HP7 active site, which was engineered to be able to accommodate a variety of porphyrin cofactors (Koder et al., 2006), enables the ready binding of the intact ZnPc dimer. In fact the bound dimeric configuration seems to be significantly lower energy than a bound monomeric configuration as the latter is not observable in these optical titrations. This is further demonstrated by the absence of ZnPc fluorescence when excited at 670 nm at low binding ratios (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Pthalocyanine binding to the bis-histidine site in HP7. 3 μM HP7-heme complex titrated with (A) zinc phthalocyanine and (B) zinc phthalocyanine monosulfonate. (C) Intensity of the exciton-coupled absorbance peak at 630nm grows linearly with ZnPc (open circles) and delayed growth with ZnPcS (closed circles) indicating that at low concentrations zinc phthalocyanine monosulfonate binds to HP7 as a monomer.

ZnPcS binding to HP7

Taking inspiration from the propionate groups found in hemin, we surmised that the addition of a charged moiety to the phthalocyanine macrocycle might destabilize the stacked ZnPc dimer by electrostatic repulsion. To simplify the synthesis and purification of the cofactor, we chose the singly charged monosulfonate of ZnPc instead of a doubly charged analogue. As Figure 2B and 2C demonstrates, the sulfonate indeed destabilizes dimer formation in HP7 somewhat – singly bound ZnPcS is present at low cofactor:protein ratios, but once the binding site is one third full only bound dimer is present. This dimeric form of ZnPcS bound in HP7 was confirmed by ESI-mass spectrometry (data not shown).

Creation of a single chain protein

The absorption spectrum of the bound ZnPcdimer, with Q-band peaks at 622 and 684 nm, is indicative of a state in which each of the ZnPc molecule is ligated to a histidine ligand (Stillman, 1993). It seemed that removing one of the two histidine residues in the binding site might destabilize the bound dimer enough to isolate a single bound ZnPc. However, the symmetry imposed on each active site by the homodimeric makeup of HP7 makes a single histidine knockout impossible. For this reason we connected two copies of the HP7 gene to each other, creating the single chain four helix bundle protein H4 (see Figure 1C). This strategy was used by Bender and coworkers to make a single chain four alpha helix bundle which binds pairs of diphenyl porphyrins (Bender et al., 2007). In order to ease future engineering efforts, each loop was constructed to contain a unique restriction site at the DNA level, which results in minor variation in each loop sequence over the original glycine and serine loops. We also removed the cysteine-based disulfides, because the disulfide cross-link is not necessary in a single-chain protein.

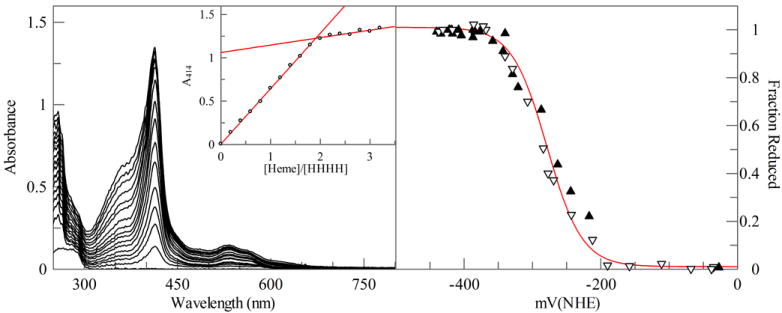

HHHH tightly binds two equivalents of oxidized hemin (see Figure 3A). A singly bound heme has a reduction potential of -286 mV vs NHE (see Table 1 and Figure 3B), a value similar to that of one heme bound to HP7 (Zhang et al., 2011a). The requirement for a large excess of apoprotein in order to ensure the reduced heme remains completely bound makes it impossible to measure the reduction potential of the diheme protein without the measured potential being increased due to a contribution from unbound reduced heme (Reedy et al., 2003). However, given the fact that the reduced binding constants for proteins in the series have generally been under 2 μM (Zhang et al., 2011a) – more than ten-fold less than the protein concentration used - we can estimate that the measured value is within 10 mV of the real value.

Figure 3.

Heme binding stoichiometery and reduction potential of the single chain protein HHHH. (A) Absorption spectra of 5 μM HHHH titrated with 1 μM aliquots of heme. Inset: Replot of the heme Soret maximum at 414 nm during the titration demonstrate that two hemes bind per molecule of HHHH. (B) Equilibrium potentiometric titration of HHHH. Line drawn is a fit with the Nernst equation with 1.0 electrons and a reduction potential of -320 mV vs NHE.

Table 1.

Spectral and binding properties

| Protein | Ferric Heme complex λmax (mM-1 cm-1) | Ferrous Heme complex λmax (mM-1cm-1) | Em (mV) | Kd, red (nM) | Kd, ox (pM)b | Ferric Heme ZnPcS complex λmax (mM-1cm-1) | Ferrous Heme ZnPcS Complex λmax (mM-1 cm-1) | λmax ZnPcS (mM-1 cm-1) | ZnPcS Fluorescence λmax (λEx=630 nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HHHF | 412 (110) | 424 (147) | -260 ± 9 | 220 ± 22 | 200 ± 200 | 412 (96) | 426 (90) | 682(111) | 689 |

| 532 (10) | 530 (12) | 532 (11) | 530 (12) | ||||||

| 558 (9) | 560 (23) | 558 (11) | 560 (17) | ||||||

| FHHH | 414 (151) | 426 (188) | -245 ± 2 | 500 ± 100 | 400 ± 70 | 414 (115) | 426 (131) | 682(105) | 690 |

| 532 (13) | 532 (15) | 532 (13) | 532 (14) | ||||||

| 558 (11) | 560 (30) | 558 (13) | 560 (24) | ||||||

| H4 | 414 (126) | 426 (204) | -286 ± 6 | > pM | |||||

| 532 (12) | 532 (17) | ||||||||

| 558 (19) | 560 (32) | ||||||||

| HP7H7Fa | 414 (129) | 428 (140) | -260 ± 6 | 600 ± 200 | 300 ± 100 | ||||

| 530 (12.8) | 532 (12.1) | ||||||||

| 558 (10.1) | 560 (20.9) |

Deletion of a histidine

The addition of ZnPcS to HHHH with a single bound heme results in the binding of a cofacial stacked dimer spectrally identical to that which is observed for HP7 with ZnPc (data not shown). In order to destabilize the dimer, we set out to remove one of the two histidine residues from one of the ZnPcS binding sites. Because there are two binding sites we created two such proteins, in both cases removing the histidine from the less constrained helix, the first and the fourth respectively. We termed the resultant proteins FHHH and HHHF, the H and F designating whether a histidine or a phenylalanine resides at the seventh position of each helix (see Figure 1B and 1C). We chose to remove these histidines as opposed to the ones on the second and third helices to reduce the probability of ZnPcS-mediated protein dimerization brought about by the rotation of ligand helix to a position facing solution, a motion more likely to occur on the less constrained terminal helices (Zhang et al., 2013). As shown below, both proteins are capable of forming the hemin:ZnPcS heterocomplex with the ZnPcS bound as a monomer.

Cofactor binding to FHHH

A single molecule of ferric heme binds to FHHH at the bis-histidine with a binding affinity too tight to extract a dissociation constant (Supplementary Figure 1A). However, the weaker ferrous heme iron-histidine interaction allows us to determine dissociation constant of 500 nM in the reduced state (Supplemental Figure 1C and Table 1) and then, in concert with the bound heme reduction potential (-245 mV vs NHE, (Supplemental Figure 2A the oxidized affinity of 400 pM can be calculated using a thermodynamic cycle (Reedy et al., 2003). These values are comparable to those observed previously for the same binding site in HP7 using the knockout mutant HP7-H7F, see Table 1 (Zhang et al., 2011a).

Figure 4A depicts the binding of ZnPcS into FHHH complexed to one molecule of hemin at the bis-histidine ligation site. A single, monomeric ZnPcS binds tightly at the monohistidine binding site during the addition of the first equivalent. Binding affinity is too tight to extract a dissociation constant, as the absorbance increase at the bound Q-band maximum of 682 nm is linear up to the equivalence point as observed by both absorption (open circles in the inset, Figure 4A) and fluorescence (Supplementary Figure 4A). However, concomitant with this increase is a linear decrease in the heme Soret peak intensity (closed circles in the inset, Figure 4A), an indication that ZnPcS binding is somehow altering the heme binding site. Heme remains bound as evinced both by the 412 nm maximum of the heme Soret band in the heterocomplex, the fact that the cofactor co-elutes with the protein in a size exclusion column (data not shown) and that after size exclusion chromatography a bound heme is found in ESI-MS spectra (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Formation of the FHHH and HHHF heterocomplexes. (A) Titration of ZnPcS into a 3 μM solution of the FHHH heterocomplex. Inset: Replot of the heme Soret peak (closed circles) and the ZnPcS Q-band peak (open circles) absorbances as a function of added ZnPCS. (B) Titration of ZnPcS into a 3 μM solution of the HHHF heterocomplex. Inset: Replot of the heme Soret peak (closed circles) and the ZnPcS Q-band peak (open circles) absorbances as a function of added ZnPCS. ZnPcS binding to FHHH is accompanied by a reduction of the heme Soret absorbance before 1 equivalent of ZnPcS is reached while HHHF loses heme Soret absorbance only after the first equivalent of ZnPcS is added.

Addition of a further two ZnPcS equivalents results in the displacement of the bound heme cofactor by a bound ZnPcS dimer, as evinced by the growth of the exciton coupled ZnPcS dimer peak at 632 nm and the loss of the heme Soret peak at 412 nm. The observed fluorescence emission intensity also reaches a maximum at one equivalent of ZnPcS, and then decreases as the bound cofacial dimer increases, presumably due to the nonfluorescent dimer reabsorbing a fraction of the emitted fluorescent photons without re-emitting them (see Supplementary Figure 4A).

Cofactor binding to HHHF

Supplemental Figures 1B, 1D and 2B depict ferric heme binding, ferrous heme binding (220 nM), and bound heme reduction potential (-260 mV vs NHE) determination respectively. These values allow the calculation of a ferric heme affinity of 200 pM (see Table 1). Figure 4B depicts the binding of ZnPcS into HHHF complexed to one molecule of hemin at the bis-histidine ligation site. Just as for hemin-complexed FHHH, a single, monomeric ZnPcS binds tightly at the monohistidine binding site during the addition of the first equivalent. However, in these titrations the heme binding site appears to be unaffected, as evinced by the constant absorbance of the heme Soret peak at 412 nm (open circles in the inset, Figure 4B) and bound heme and ZnPcS is found in ESI-MS spectra (supporting figure 3). After a full equivalent binds, the heme is again displaced by ZnPcS dimers upon addition of additional ZnPcS (closed circles, inset, Figure 4B).

Comparison of the two heterocomplex forms

Despite the identical sequence of helices in both binding sites, several differences are apparent between the two single chain heterocomplexes (Table 2): the HHHF heterocomplex has a narrower principle Q-band as compared to the FHHH heterocomplex, with a higher extinction coefficient and a more pronounced side band feature at 612 nm (See Figure 5B). The heme Soret peak is similarly narrower and higher in extinction coefficient in HHHF as opposed to the FHHH complex, this is a result of the latter’s heme binding site Soret peak decrease which was found to be coupled to ZnPcS binding. The heterocomplex also has a fluorescent emission almost 60% higher in intensity with a maximum redshifted by 1 nm.

Figure 5.

Absorption and MCD spectral data for ZnPcS in DMF. The ZnPcSspectra resembles a typical Pc spectra with a strong Q band at 672 nm and associated vibronic bands. all of which is echoed in the MCD spectra. The B band centered on ca. 343 nm is very weak in the MCD spectrum as is usual, the negative-positive signals allow a width of 41 nm and a crossover of 347 nm to be identified matching the absorption spectrum closely.

As the amino acidsequence of each helix is identical, the observed differences in heme:ZnPcS heterocomplex formation are most likely due to topology differences in the loop structures at the two binding sites. ZnPcS is a bulkier macrocyle as compared to hemin (Figure 1A), and it is likely that in HHHF the ZnPcS cofactor can bind between helices two and four without steric interference from the loops which connect the helices on that end of the protein – these loops, the one connecting helices one and two and the one connecting helices three and four, are parallel to the plane of the ZnPcS macrocycle. On the other end of the protein the loop which connects helices two and three connects diagonally across the bundle, and this likely sterically affects ZnPcS binding at that end of the protein, altering the ZnPcS binding geometry in such a way as to affect the heme binding site at the other end of the protein. The modeled distance between the two cofactors (9 Å) makes it unlikely that there is actual steric contact between them, thus it seems more likely that one or both of the heme binding helices is affected.

MCD spectroscopy of ZnPcS complexes

MCD spectroscopy is a powerful tool to examine protein based ligands of heme and additionally the heme oxidation and spin state (Tiedemann and Stillman, 2011). MCD spectroscopy has also been shown to provide detailed information about phthalocyanine excited states (Kobayashi and Katsunori, 2007; Mack et al., 2007; Mack et al., 2005). The π to π* transitions of porphyrins and phthalocyanines are normally observed in the absorption spectrum as B and Q bands. These bands are observed with greater resolution in the MCD spectrum. The black line in Figure 5 shows the absorption and MCD spectra of heme bound HP7, FHHH and HHHF. For HP7, Figure 5A black line, the spectra closely resemble the other heme-bound protein spectra (FHHH and HHHF, Figure 5B and C respectively). The B band at 413 nm in the absorption spectra is echoed in the MCD spectra at (+)407 and (-)422 with a crossover of 413 nm. Similar results are seen with FHHH and HHHF. FHHH (Figure 5B) has the B band at 414 nm in the absorption spectra and corresponding bands at (+)406 nm and (-)421 nm with a crossover of 413 nm. HHHF (Figure 5C) has the B band at 413 nm in the absorption spectra and corresponding bands at (+)405 nm and (-)420 nm with a crossover of 412 nm. Heme binding to all three proteins is confirmed by the large B band shift for free heme at ~390 nm to a ligand bound wavelength at ~410 nm (Shimizu et al., 1976; Tiedemann and Stillman, 2012). This series of heme-bound absorption and MCD spectral data match very closely the spectral data for ferric myoglobin, which indicates that the heme is bound by the expected histidine residue. This interpretation arises from the band maxima of ~414 nm for the B band and strong B band MCD signal and the characteristic 555/573 nm Q band region for HP7, 555/575 nm Q band region for FHHH and 556/574 nm Q band region for HHHF (Pluym et al., 2007; Vickery et al., 1975).

The red line in Figure 5 shows the absorption and MCD spectra of heme and ZnPcS bound HP7, FHHH and HHHF. In all three absorption and MCD spectra the underlying heme bound spectra have not significantly changed. This indicates that ZnPcS binding has not perturbed the heme binding environment and that the histidine remains as the heme binding ligand. Also, present in the absorption and MCD spectra of FHHH and HHHF are typical phthalocyanine signals (absorption and MCD spectral data for ZnPcS can be found in supplemental figure 5). For FHHH, Figure 5B, we now observe a strong ZnPcS Q band at 683 nm which is reflected in the MCD spectra as a very intense band at (+)672 and (-)685 nm. The Qvib band is at 626 nm, which is off-center in the MCD spectra at (+)626 nm. Interestingly, the B band of the bound ZnPcS is quite intense in the absorption at 348 nm, however, it is quite weak in the MCD spectra. The same phenomenon is observed with heme and ZnPcS bound HHHF(red line in Figure 5C). A strong ZnPcS Q band signal is observed at 682 nm with a Qvib at 613 nm. These bands are echoed in the MCD spectral data at (+)672 nm and (-)685 nm for the Q band and (+)614 nm.

The absorption and MCD signal for heme and ZnPcSbound HP7, red line in Figure 5A, is quite different from FHHH and HHHF. The Q band of the ZnPcS is split into two bands at 634 nm and 685 nm. This is then reflected in the overlapping bands in the MCD spectrum at (+)625, (-)657, (+)683 and (-)701 nm. This split Q band phenomena with a single B band, located at 349 nm in the absorption spectra, is typical of homo-dimer phthalocyanines (Kobayashi, 2002).

Electronic and energetic coupling between the cofactors

The possibility exists that the two cofactors in HHHF may act as an electron transfer dyad (Gust et al., 2001), with light-activated electron transfer occurring from the ZnPcS to the oxidized heme and then back again (Alstrum-Acevedo et al., 2005). Another possibility is that there may be through space resonance energy transfer from the excited state ZnPcS to the heme in a manner similar to that seen between chlorophylls and carotenoids (McConnell et al., 2010). One way to ensure that the ZnPcS exists in isolation is to remove the heme cofactor from the heterocomplex. However, for both FHHH and HHHF addition of a single equivalent of ZnPcS in the absence of a bound heme results in the binding of a ZnPcS dimer to half of the bis-histidine sites (not shown). Attempts to remove the bis-histidine site completely, resulting in the proteins FFHF and FHFF, resulted in a protein which does not bind even a single ZnPcS, indicating that the initial heme binding event preorganizes the ZnPcS site (not shown).

Both electron transfer and resonance energy transfer from the excited state will result in a reduction in fluorescence intensity observed upon ZnPcS excitation, due to the concomitant loss of the excitation required for fluorescence emission (Turro, 1991). Excited state electron transfer can be precluded by the fact that in anaerobic solution the ZnPcS fluorescence emission spectrum is identical when the heme is either oxidized or reduced. Resonant energy transfer can be precluded on the basis of fluorescence excitation spectra – no ZnPcS fluorescence can be observed upon excitation of the heme Soret or Q-band absorbance peaks.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated a pathway to the singular binding, in electronic and photonic isolation, of one of the most important primary donor cofactors in artificial photosynthesis. Strategic placement of histidine residues within a binary patterned four-helix bundle protein yields monomerically bound cofactor analogues by simple metal ligand coordination. Despite the fact that we have not added any specific internal packing residues (Negron et al., 2009) intended to enhance binding, we observe that binding of both the ferric heme and ZnPcS residues have nanomolar affinities. The engineering guidelines determined here, which enable the simple insertion of a monomeric ZnPc binding site into an artificial helical bundle, are a robust starting point for the creation of functional photoactive nanodevices.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Marilyn Gunner of the Department of Physics, the City College of New York, for many helpful discussions. RLK gratefully acknowledges support by the following grants: MCB-0920448 from the National Science Foundation, infrastructure support from the NIH National Center for Research Resources to CCNY (NIH 5G12 RR03060). ACM gratefully acknowledges support from the Center for Exploitation of Nanostructures in Sensor and Energy Systems (CENSES) under NSF Cooperative Agreement Award Number 0833180. MJS gratefully acknowledges support from the NSERC of Canada for Discovery and Research Tools Grants; Academic Development Fund at the University of Western Ontario. MTT gratefully acknowledges NSERC of Canada Graduate Scholarship support.

References

- Alstrum-Acevedo JH, Brennaman MK, Meyer TJ. Chemical approaches to artificial photosynthesis. 2. Inorg Chem. 2005;44:6802–6827. doi: 10.1021/ic050904r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender GM, Lehmann A, Zou H, Cheng H, Fry HC, Engel D, Therien MJ, Blasie JK, Roder H, Saven JG, DeGrado WF. De novo design of a single-chain diphenylporphyrin metalloprotein. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:10732–10740. doi: 10.1021/ja071199j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg KA, Abeles RH. Mechanism of action of plasma amine oxidase products released under anaerobic onditions. Biochemistry. 1980;19:3186–3189. doi: 10.1021/bi00555a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry EA, Trumpower BL. SIMULTANEOUS DETERMINATION OF HEMES-A, HEMES-B, AND HEMES-C FROM PYRIDINE HEMOCHROME SPECTRA. Anal Biochem. 1987;161:1–15. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90643-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewis M, Hassan BM, Li H, Makhseed S, McKeown NB, Thompson N. The synthetic quest for ‘splendid isolation’ within phthalocyanine materials. Journal of Porphyrins and Phthalocyanines. 2000;4:460–464. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Ofri I, van Gastel M, Grzyb J, Brandis A, Pinkas I, Lubitz W, Noy D. Zinc-Bacteriochlorophyllide Dimers in de Novo Designed Four-Helix Bundle Proteins. A Model System for Natural Light Energy Harvesting and Dissipation. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2011;133:9526–9535. doi: 10.1021/ja202054m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d’Alessandro N, Tonucci L, Morvillo A, Dragani LK, Di Deo M, Bressan A. Thermal stability and photostability of water solutions of sulfophthalocyanines of Ru(II), Cu(II), Ni(II), Fe(III) and Co(II) Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 2005;690:2133–2141. [Google Scholar]

- de la Torre G, Claessens CG, Torres T. Phthalocyanines: old dyes, new materials. Putting color in nanotechnology. Chemical Communications, 2000-2015. 2007 doi: 10.1039/b614234f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibney BR, Rabanal F, Skalicky JJ, Wand AJ, Dutton PL. Design of a unique protein scaffold for maquettes. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:2323–2324. [Google Scholar]

- Gibney BR, Isogai Y, Rabanal F, Reddy KS, Grosset AM, Moser CC, Dutton PL. Self-assembly of heme A and heme B in a designed four-helix bundle: Implications for a cytochrome c oxidase maquette. Biochemistry. 2000;39:11041–11049. doi: 10.1021/bi000925r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gust D, Moore TA, Moore AL. Mimicking photosynthetic solar energy transduction. Accounts Of Chemical Research. 2001;34:40–48. doi: 10.1021/ar9801301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SS, Koder RL, Lewis M, Wand AJ, Dutton PL. The HP-1 maquette: From an apoprotein structure to a structured hemoprotein designed to promote redox-coupled proton exchange. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:5536–5541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306676101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi N. Dimers, trimers and oligomers of phthalocyanines and related compounds. Coordination Chem Rev. 2002;227:129–152. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi N, Katsunori N. Applications of magnetic circular dichroism spectroscopy to porphyrins and phthalocyanines. Chem Commun. 2007:4077–4092. doi: 10.1039/b704991a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koder RL, Anderson JLR, Solomon LA, Reddy KS, Moser CC, Dutton PL. Design and engineering of an O2 transport protein. Nature. 2009;458:305–309. doi: 10.1038/nature07841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koder RL, Valentine KG, Cerda JF, Noy D, Smith KM, Wand AJ, Dutton PL. Native-like structure in designed four helix bundles driven by buried polar interactions. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:14450–14451. doi: 10.1021/ja064883r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack J, Stillman MJ. Transition assignments in the ultraviolet-visible absorption and magnetic circular dichroism spectra of phthalocyanines. Inorganic Chemistry. 2001;40:812–814. doi: 10.1021/ic0009829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack J, Stillman MJ, Kobayashi N. Application of MCD spectroscopy to porphyrinoids. Coordination Chem Rev. 2007;251:429–453. [Google Scholar]

- Mack J, Yoshiaki A, Kobayashi N, Stillman MJ. Application of MCD Spectroscopy and TD-DFT to a Highly Non-Planar Porphyrinoid Ring System. New Insights on Red-Shifted Porphyrinoid Spectral Bands. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:17697–17711. doi: 10.1021/ja0540728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell I, Li GH, Brudvig GW. Energy Conversion in Natural and Artificial Photosynthesis. Chemistry & Biology. 2010;17:434–447. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negron C, Fufezan C, Koder RL. Helical Templates for Porphyrin Binding in Designed Proteins. Proteins-Structure Function And Bioinformatics. 2009;74:400–416. doi: 10.1002/prot.22143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluym M, Vermeiren CL, Mack J, Heinrichs DE, Stillman MJ. Heme Binding Properties of Staphylococcus aureus IsdE. Biochem. 2007;46:12777–12787. doi: 10.1021/bi7009585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punnoose A, McConnell LA, Liu W, Mutter AC, Koder RL. Fundamental Limits on Wavelength, Efficiency and Yield of the Charge Separation Triad. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36065. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawling T, McDonagh A. Ruthenium phthalocyanine and naphthalocyanine complexes: Synthesis, properties and applications. Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 2007;251:1128–1157. [Google Scholar]

- Reedy CJ, Kennedy ML, Gibney BR. Thermodynamic characterization of ferric and ferrous haem binding to a designed four-alpha-helix protein. Chemical Communications. 2003:570–571. doi: 10.1039/b211488g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson DE, Farid RS, Moser CC, Urbauer JL, Mulholland SE, Pidikiti R, Lear JD, Wand AJ, Degrado WF, Dutton PL. Design and Synthesis of Multi-Heme Proteins. Nature. 1994;368:425–431. doi: 10.1038/368425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutte WJ, Sluytersrehbach M, Sluyters JH. Aggregation Of An Octasubstituted Phthalocyanine In Dodecane Solution. Journal Of Physical Chemistry. 1993;97:6069–6073. [Google Scholar]

- Shifman JM, Gibney BR, Sharp RE, Dutton PL. Heme redox potential control in de novo designed four-alpha- helix bundle proteins. Biochemistry. 2000;39:14813–14821. doi: 10.1021/bi000927b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu T, Nozawa T, Hatano M. Magnetic Circular Dichroism Studies of Pyridine-Heme COmplexes in Aqueous Media. Bioinorganic Chemistry. 1976;6:119–131. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3061(00)80046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smagghe BJ, Trent JT, Hargrove MS. NO Dioxygenase Activity in Hemoglobins Is Ubiquitous In Vitro, but Limited by Reduction In Vivo. PLoS One. 2008;3 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stillman M. Formation and electronic properties of ring-oxidized and ring-reduced radical species of the phthalocyanines and porphyrins. Journal of Porphyrins and Phthalocyanines. 2000;4:374–376. [Google Scholar]

- Stillman M, Mack J, Kobayashi N. Theoretical aspects of the spectroscopy of porphyrins and phthalocyanines. Journal of Porphyrins and Phthalocyanines. 2002;6:296–300. [Google Scholar]

- Stillman MJ. Phthalocyanines: Properties and Applications. John Wiley and Sons; 1993. Absorption and Magnetic Circular Dichroism Spectral Properties of Phthalocyanines. [Google Scholar]

- Tiedemann MT, Stillman MJ. Application of magnetic circular dichroism spectroscopy to porphyrins, phthalocyanines and hemes. Journal of Porphyrins and Phthalocyanines. 2011;15:1134–1149. [Google Scholar]

- Tiedemann MT, Stillman MJ. Heme binding to the IsdE(M78A; H229A) double mutant: challenging unidirectional heme transfer in the iron-regulated surface determinant protein heme transfer pathway of Staphylococcus aureus. J Biol Chem. 2012;17:995–1007. doi: 10.1007/s00775-012-0914-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turro NJ. Modern Molecular Photochemistry. University Press; Menlo Park: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Vickery L, Nozawa T, Sauer K. Magnetic Circular Dichroism Studies of Myoglobin Complexes. Correlations with Heme Spin State and Axial Ligation. J Am Chem Soc. 1975;98:343–350. doi: 10.1021/ja00418a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Andersen EME, Khajo A, Maggliozzo RS, Koder RL. Dynamic factors affecting gaseous ligand binding in an artificial oxygen transport protein. Biochemistry. 2013;52:447–455. doi: 10.1021/bi301066z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Anderson JLR, Ahmed I, Norman JA, Negron C, Mutter AC, Dutton PL, Koder RL. Manipulating Cofactor Binding Thermodynamics in an Artificial Oxygen Transport Protein. Biochemistry. 2011a;50:10254–10261. doi: 10.1021/bi201242a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Anderson JLR, Ahmed I, Norman JA, Negron C, Mutter AC, Dutton PL, Koder RL. Manipulating cofactor binding thermodynamics in an artificial oxygen transport protein. Biochemistry. 2011b;50:10254–10261. doi: 10.1021/bi201242a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.