Abstract

In response to the commentary(1) in this month’s Canadian Geriatrics Journal by Andrew and Rockwood on the recent paper I co-wrote with King’s Fund colleagues—“Making Health and Care Systems Fit for an Ageing Population”(2)—I wanted to pen a very personal response, not least because of my visits to health systems in Ontario and Alberta and conversations with many Canadian colleagues that are fresh in my mind. The paper was certainly the most important and influential thing I have written, and was an attempt to weave all the elements of good practice in health care for older people into one overarching narrative. Whilst its biggest target audience is UK health services, I hope it has some relevance to Canada and might stimulate some constructive conversations.

Keywords: older people, health services, quality integration

How I Came To Write the Paper

In addition to my “day job” as a busy hospital-based geriatrician, I have played some national leadership roles. I spent four years seconded alongside my clinical work to the English Department of Health as the National Clinical Director for Older Peoples. I am currently President of the British Geriatrics Society (BGS) and lead work on integrated care for older people at the King’s Fund—an influential health policy think tank. Working for the NHS Emergency Care Support Team, I have also helped a number of hospitals with external input on their acute care pathways for frail older people.

This has taken me out on the road, into numerous health services. I now have a much better understanding of “who is doing what and where?” to improve services for older people; equally important, to an understanding of “what is going wrong and why?” Encouragingly, many clinical colleagues are leading fantastic innovations in care delivery and quality improvement in their services. Even so, we are bad at disseminating and implementing these models, and at using our expertise to help colleagues in other services.

Most importantly, these roles have taken me beyond my narrower training and career as a hospital doctor “doing medicine”, and made me aware of a much wider world, which perhaps, as doctors, we need to get better at engaging with. I have had a ringside seat in government, in health policy and leadership, and seen how agendas are influenced and how specialist clinicians can be marginalised in the “big conversations”. I have broadened my understanding of other services, clinical disciplines, and sectors—how they think, what their values and pressures are, and how they perceive geriatric medicine and the care of older people.

Our speciality has much to be proud of in developing an evidence base for the clinical interventions and service models, in battling ageism, in ensuring that older people with frailty and complex co-morbidities can access the same standard of skilled care we would expect for younger people, and in helping to train a wide variety of clinical staff. Indeed, the Commentary’s mention of the Grimley-Evans and Tallis(3) heartfelt response to the push for more “intermediate care” places set out in the UK 2001 National Service Framework(4) illustrates this tale. United Kingdom geriatricians of that generation had fought hard to ensure that frail older people received full diagnostic assessment and were not “written off”, denied the full facilities of the acute general hospital, and warehoused in long-stay wards. Understandably they worried about clocks turning back but, if services never changed, then the speciality of Geriatrics would never have gained a post-war foothold.

Why Population Ageing Is a “Game-Changer” for Health and Care Services and for Geriatric Medicine

All clinical specialities evolve with changes in demography, technology, training, and public attitudes. And, for geriatric medicine, rapid population ageing is a “game changer”. In England, people at 65 can already expect to live around two more decades.(5) By 2030, a man at 65 can expect to live, on average, till 88 and a woman till 91. The number of “oldest old” (those over 85) has doubled over the past two decades.(6) Canadian ageing looks pretty similar.(7)

This demographic shift means far more older people—many living with multiple long-term conditions,(8) especially including frailty,(9) dementia or functional impairment,(10) or on multiple medications.(11) More older people rely on informal care from friends or family,(12) use multiple services, and see multiple professionals.(13,14) In turn, this means too often their care is fragmented and poorly co-ordinated, and that care transitions are problematic and distressing when they value continuity and co-ordinated care based around their needs rather than professional silos.(15,16,17) Most importantly, whether we consider acute hospital services, primary care or those “step up” and “step down” intermediate care services(18) mentioned in the Commentary, older people with complex needs now account proportionally for the biggest activity, the biggest spend, and the biggest variation and care gaps.

The growing number of patients with complex needs means that the traditional focus in hospital specialism or primary care incentives on single disease or organs needs to shift dramatically to one of personalised, co-ordinated care, based on individual need. In short, we need more “expert generalism” and to achieve this, the training offer for doctors and other practitioners needs to follow suit.

In the UK, we have lost around one third of our acute hospital beds over the past two decades, even though urgent admissions have risen and length of stay fallen inexorably.(19) The financial crash has led to a “flat funding” settlement for the NHS and cuts to our social care system.(20) And acute hospitals run very close to full, with big pressures in emergency rooms and often significant delays getting older patients back home again.

When the number of such patients were fewer, when there was less pressure on hospital beds, it may have been possible for the niche speciality of geriatrics to admit them to beds and to keep them there under specialist care, till all assessment and intervention was complete. Now, they are everywhere in the system, and all of us have a stake in getting their care right. And if we don’t get it right it will be impossible to meet (in any western health system) the increasing activity and financial pressures on health and care services.

And although the evidence base for ward-based Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment in hospital is good,(21) hospitals are far from “places of safety” for older people who are at risk of a number of harms related to hospitalization, as well as institutionalisation, and loss of function and confidence.

So long as patients are not denied expert diagnostic assessment and the full skills of the multidisciplinary team, “intermediate care” and “discharge to assess” should not be dirty words. Frail older people lose function in the face of acute illness and require adequate rehabilitation. But much of this can be delivered in the home or in less hectic community facilities. Ideally, older people should only be in an acute bed for as long as it is adding value to their care. Try this simple experiment—ask yourself on a ward round, “If I saw this person on call in the emergency department today, would I admit them?” A growing range of models in the UK have focussed on expert geriatric assessment at the front door of the hospital,(2,22) often with “in reach” and “pull” from community services, and a real focus on better discharge planning. Results can be dramatic, both for patients and for bed occupancy.(23)

How We Designed the King’s Fund Paper—the Ten Components of Care

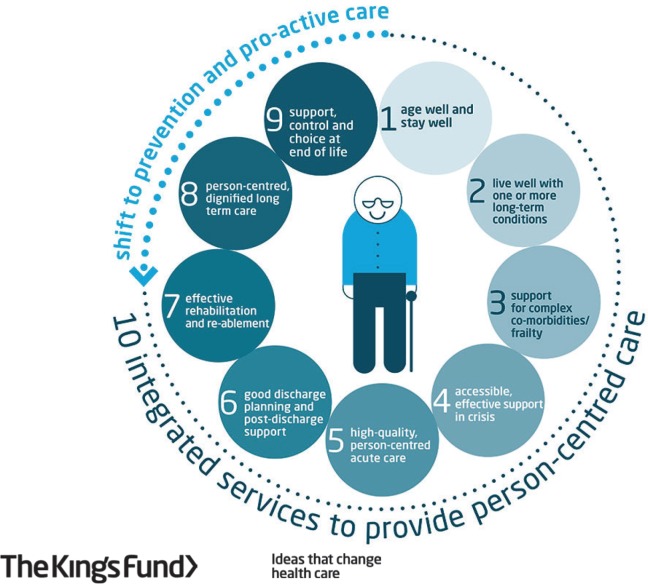

In writing the paper for the King’s Fund, my co-authors and I aimed to set out in one accessible, practical resource, “what good looks like” at every stage of care and support for our oldest citizens, from healthy active ageing right through to care and support at the end of life. In doing so, we designed a schema of nine “components of care” that any service leader, clinician or policy-maker could hang their hat on and use to “walk the journey of care” in their own services.

Most geriatricians in the UK are working in components four to seven—the acute hospital-based care pathway with some cross over at the interface to rapid community responses and post-acute intermediate care. We do have a growing number of colleagues taking on “community geriatrics” roles and, therefore, working in the other components such as nursing and residential care, community case management, and end of life care outside hospital.

We wrapped these nine components around a typical older patient—in this case Sam—who has his own animation to focus minds(24) on who we are doing all this for and move people away from focussing on structures and processes and finance. Many health economies in the UK have based their service redesign around their own eponymous typical older patient with extensive input from real ones. The tenth component, binding the others together, was the need to shift towards prevention and wellbeing and away from reactive bed-based care, and towards integration to deliver more person-centred co-ordinated care. All this is illustrated in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Ten components of care

Why We Wrote the Paper and Who We Wrote It For

In answer to the Question I posed in the above title, we wrote it for any collaboration of local leaders in health and social care wanting to learn “what good looks” like in each component of care, illustrated with practical examples of service innovation and key guidelines. We wanted to help them to look at the hand-offs, duplications, and inefficiencies between components of care, and help make services more genuinely integrated around the person’s needs. There wasn’t a similar all-encompassing resource out there; hence, the big interest the paper has received.

It certainly can be useful to geriatricians trying to sell the key messages about what they do to local non-geriatrician colleagues and, in turn, to understand better some of the service models outside their own practice. But it’s aimed as much at non-specialists.

This latter point is especially important to me, because for too long I think geriatrics as a speciality has looked inwards. We have tended to abstract, solipsistic debates about the nature of frailty or the nature of CGA, whilst out there in the big bad world, many older people are failing to receive the skilled care and assessment they require. We can’t, after all, look after everyone.

We haven’t always been great at explaining to others what we offer and persuading them of our worth. The care of our most vulnerable citizens should, after all, be a matter of great pride, yet the speciality has often been regarded as a “Cinderella”—way down the unwritten, but understood, hierarchy of prestige and influence. Nor have we been clear enough about where we, as specialists, must be involved and where other disciplines can provide what is needed so long as we help them to up-skill and learn how to deal with frailty, multi-morbidity, and complexity and deliver Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment.

Will the Ideas in the Paper Translate to Canadian Colleagues and Context?

My final rhetorical question was about transferability of lessons to Canadian provinces. Canadian colleagues are far better placed to comment on the readiness of their own system for some of these messages, so I pose the question to stimulate debate.

Andrew and Rockwood(1) may glance enviously over at the UK where geriatricians are more numerous and “mainstream” than any nation. We are the biggest Internal Medicine speciality in the Royal College of Physicians, with the biggest number of trainees. The BGS has around 2,500 doctor-members (and several hundred from nursing and allied professions), with around 1,300 consultants, for a population of 62 million—a higher ratio than Canada. And because most geriatricians are also highly trained in acute (all age) general internal medicine, with many more trained in stroke, we are integral to service delivery in general hospitals and, as a result, more in the “mainstream”.

Our system also allows genuinely national quality improvement initiatives, such as the hip fracture database and dementia strategy. Our politicians, National Health Services (NHS) leaders, and the Royal College in its Future Hospitals Commission(25) and Future Hospital Workforce Review(26) have all realised that we need a sea change towards care co-ordination, prevention, integration, and towards making services fit for the older people who use them, with a greater focus on “expert generalism”. And the “triple threat” of ageing demographics, funding squeezes, and too many reports on poor care quality mean that the care of older people is in the spotlight as never before.

But even in the UK, Geriatric Medicine can’t begin to look after all older people living with frailty, even those admitted to hospital—there are just too many. So we need to be clear in our narrative of our specific place in the world order.

If we are badging our skills as the solution to improving care quality, then we need to step up to the plate and deliver. We need to stop navel gazing, get out there and evangelise and up-skill other clinicians. Most importantly, we should seek to understand the perspectives and challenges for other professional disciplines, and collaborate more effectively with them in helping to solve wicked system problems, like the growing burden of long-term conditions and frailty and the growing pressure on acute beds. Speciality silos and professional territorialism won’t work in the twenty-first century. Let’s walk the walk of designing services around the older person using them. It would be a “win/win” for them and for our wider health and care systems.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The authors declare that no conflicts of interest exist.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andrew M, Rockwood K. Making our health and care systems fit for an ageing population: considerations for Canada. Can Geriatr J. 2014;17(4):133–5. doi: 10.5770/cgj.17.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oliver D, Foot C, Humphries R. Making our health and care systems fit for an ageing population. London, UK: King’s Fund; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grimley Evans J, Tallis RC. A new beginning for care for elderly people? Not if the psychopathology of this national service framework gets in the way. BMJ. 2001;322(7290):807–08. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Health. National service framework for older people (in England) London, UK: Department of Health; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Office for National Statistics. Life expectancy at birth and at 65 for local areas in England and Wales 2010–12. London, UK: ONS; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wise J. Number of “oldest old” has doubled over the past 25 years. BMJ. 2010;340:3057. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Employment and Social Development Canada. Canadians in context – aging population. Ottawa: HRSDC; 2012. Available from: http://www4.hrsdc.gc.ca/.3ndic.1t.4r@-eng.jsp?iid=33. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnett K, Mercer S, Norbury M, et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2012;380(9386):37–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, et al. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381(9868):752–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melzer D, Tavakoly B, Winder R, et al. Health care quality for an active later life; improving quality of prevention and treatment through information: England 2005–2012. A report from the Peninsula College of Medicine and Dentistry Ageing Research Group for Age UK. Exeter, UK: University of Exeter; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duerden M, Avery T, Payne R. Polypharmacy and medicines optimisation. Making it safe and sound. London, UK: Kings Fund; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12. House of Lords. Ready for Ageing? Select committee on public service and demographic change. Report of session 2012–13. London. 2013.

- 13.NHS England Safe, compassionate care for frail older people, using an integrated care pathway. Redditch, UK: NHS England; 2013. Available from: http://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/safe-comp-care.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.NHS Confederation and Royal College of General Practitioners. Making integrated out-of-hospital care a reality. London, UK: NHS Confederation; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roland M, Paddish C. Better management of patients with multimorbidity. BMJ. 2013;346:2510. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haggerty J. Ordering the chaos for patients with multimorbidity [editorial] BMJ. 2012;345:4515. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellins J, Glasby J, Tanner D, et al. Understanding and improving transitions of older people; a user and carer centred approach. Final Report. National Institute for Health Research Service Delivery and Organisation Programme; London, UK: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18.NHS Benchmarking. National audit of intermediate care report. Second Round. Manchester, UK: NHS Benchmarking Network; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Appleby J. The hospital bed: on its way out? BMJ. 2013;346:1563. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nuffield Trust. Future health and social care funding in England. London, UK: Nuffield Trust; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ellis G, Whitehead M, Robinson D, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older people admitted to hospital: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2011;343:6553. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d6553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.British Geriatrics Society, College of Emergency Medicine, Society of Acute Medicine, and others. Quality care for older people with urgent and emergency care needs. The Silver Book; London, UK: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silvester K, Mohammad M, Harriman P, et al. Timely care for frail older people referred to hospital improves efficiency and reduces mortality without the need for extra resources. Age Ageing. 2014;43(4):472–77. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The King’s Fund. Joined-up care: Sam’s Story. London, UK: King’s Fund; 2013. Available from: http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/audio-video/joined-care-sams-story. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Royal College of Physicians of London. Future hospital: caring for medical patients. The Future Hospitals Commission, Final Report. London, UK: RCP; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Royal College of Physicians of London. Hospital workforce: fit for the future? The Future Hospital Workforce. London, UK: RCP; 2013. [Google Scholar]