Abstract

Objective

To describe salient experiences with a primary care visit (e.g., the context leading up to the visit, the experience and/or outcomes of that visit) for emotional, personal and/or mental health problems older Latinos with a history of depression and recent depressive symptoms and/or antidepressant medication use reported 10 years after enrollment into a randomized controlled trial of quality-improvement for depression in primary care.

Design

Secondary analysis of existing qualitative data from the second stage of the continuation study of Partners in Care (PIC).

Participants

Latino ethnicity, age ≥ 50 years, recent depressive symptoms and/or antidepressant medication use, and a recent primary care visit for mental health problems. Of 280 second-stage participants, 47 were eligible. Both stages of the continuation study included participants from the PIC parent study control and 2 intervention groups, and all had a history of depression.

Methods

Data analyzed by a multidisciplinary team using grounded theory methodology.

Results

Five themes were identified: beliefs about the nature of depression; prior experiences with mental health disorders/treatments; sociocultural context (e.g., social relationships, caregiving, the media); clinic-related features (e.g., accessibility of providers, staff continuity, amount of visit time); provider attributes (e.g., interpersonal skills, holistic care approach).

Conclusions

Findings emphasize the importance of key features for shaping the context leading up to primary care visits for help-seeking for mental health problems, and the experience and/or outcomes of those visits, among older depressed Latinos at long-term follow-up, and may help tailor chronic depression care for the clinical management of this vulnerable population.

Keywords: depression, aging, Latino, primary care

Introduction

Depression is one of the most common and disabling conditions affecting older adults.1 Late-life depression is associated with increased morbidity and mortality.2 Older minorities tend to seek help for depression in non-mental health settings, particularly primary care medicine.3 Although effective treatments for late-life depression exist and rates of diagnosis and treatment are increasing, many older adults in primary care settings remain undertreated, and older minorities are particularly unlikely to receive depression treatment.4

Older adult depression is often chronic and recurrent.5 Prior work has demonstrated that major depressive disorder is unremitting in 15% of cases and recurrent in 35%.6 In a meta-analysis of 11 randomized trials that included depressed patients successfully treated with acute pharmacotherapy who were then assigned to placebo versus active maintenance treatment, the relative risk of relapse at 1 year on placebo was 51% compared to 23% in the active treatment; at 2 years, it was 62% and 34% respectively.7 Because of the chronic and recurrent nature of depression, knowing more about older adults’ experiences of seeking and experiencing primary care for depression at long-term follow-up is relevant and important, and may help inform the clinical management of chronic depression in this vulnerable population. Few studies, however, have examined experiences with primary care visits for depression among older adults at long-term follow-up.

Data from the qualitative second-stage of the Partners in Care (PIC) continuation study, conducted 10 years after enrollment into a randomized controlled trial of quality improvement for depression in primary care, afforded an unique opportunity to examine experiences with primary care visits for emotional, personal and/or mental health problems at long-term follow-up among older Latinos with a history of depression and recent depressive symptoms and/or antidepressant medication use. The aim of our study was to describe the salient themes that emerged when older depressed Latinos discussed the context leading up to a visit in primary care for an emotional, personal and/or mental health problem, and the experience and outcomes of their visit.

Methods

Study Design

We conducted a secondary analysis of existing qualitative data from the second-stage of the PIC continuation study.

Data Source

The data we employed were from the help-seeking event module of the qualitative interviews that were conducted in the second stage of the PIC continuation study. The methods and instrument that were employed for the qualitative interviewing are presented below.

The parent PIC study has been described elsewhere.8 Briefly, PIC was a group-level randomized controlled trial of primary care quality-improvement interventions for depression. Clinics in 4 geographic areas were randomized to enhanced usual care or to one of two QI programs for depression featuring team management, provider and patient education, case management plus enhanced resources for either medication management (QI-Meds) or Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (QI-Therapy).

The two-stage PIC continuation study included the control and the 2 intervention groups from the parent study. The continuation study consisted of a structured quantitative survey of the full PIC sample 9 years after study enrollment (Stage 1), followed by qualitative interviewing (Stage 2) with all minorities and a matched subsample of whites who completed the 9-year quantitative survey. The qualitative interviewing comprised 3 interviews per participant, and was conducted approximately 10 years after PIC study enrollment. Not all participants completed all 3 interviews. Stage 1’s aim was to examine long-term intervention effects; Stage 2’s aim was to report the ways PIC participants – all with a history of depression – described recent experiences with stress, depression, help-seeking, and coping.

Analytic Sample

Of participants who completed the 9-year quantitative survey (i.e., Stage 1 of the two-stage continuation study), all African-Americans (n=46) and Latinos (n=205), and a subsample (n=108) of whites matched on site, clinic intervention assignment and gender to the minority sample, were invited to participate in the qualitative interviews (i.e., Stage 2 of the two-stage continuation study). Thirty-seven African-Americans, 157 Latinos and 86 whites completed at least one interview. Across the 3 groups, 259 completed at least 2 interviews, 250 completed all 3.

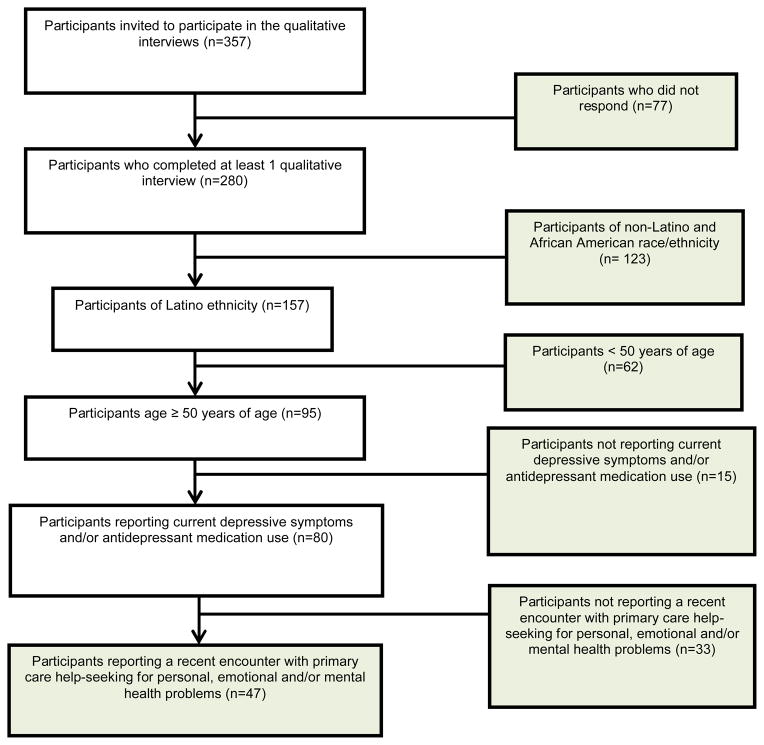

Our sample was drawn from participants who completed at least one qualitative interview. Eligibility criteria included: Latino ethnicity, age ≥ 50 years, having recent depressive symptoms and/or antidepressant medication use (as identified in the qualitative interview event screener; see below), and having describing a recent primary care visit for emotional, personal and/or mental health problems. Of 280 qualitative interview participants, 95 were older Latinos; of these, 47 were eligible and were included in our analysis (Appendix).

Qualitative Interviewing Methods and Instrument

The qualitative interviewing consisted of 3 semi-structured recorded telephone interviews conducted over 3 months per participant. The interviews were conducted in English or Spanish by trained, bilingual interviewers.

At the beginning of each interview, participants were asked a help-seeking event screener (“Please think about the last 30 days and tell me all of the health or community service helpers with whom you talked about an emotional, personal, or mental health problem, even if you only discussed the problem briefly.”) Participants were also screened for any of 5 other events: depressive symptoms, antidepressant medication use, stressful events, proactive coping, and positive life events. Events with a positive screener were then explored in an event module specific to each event.

In the help-seeking event module, participants were asked open-ended questions to encourage them to freely and spontaneously describe what was meaningful to them about seeking care, a design consistent with the nature and goals of grounded theory analysis.9 Participants were first asked a general question about their help-seeking experience (“Please tell me about that experience. Tell me about the events that led up to it, what happened during the experience, and the effect it had for you and the problems you were having”). To help participants articulate their narrative about the help-seeking experience, interviewers were trained to ask additional open-ended questions, or probes (e.g., “We want to learn how people decide to seek care, what gets them to pick treatments, what difficulties and barriers they face, their hopes and fears of seeking help, what others think of them for seeking help, and overall what the experience is like to seek help,” “What else was going on in your life,” “Who was involved,” “What were you thinking,” “How did you feel,” “What did you do,” “How was it similar or different to situations in the past”). Consequently, participants focused on different issues depending on their perspective and what was important to them, resulting in rich data on the features of seeking care that were most salient to participants.

The qualitative interviewing included 3 qualitative interviews per participant to maximize the exploration of as many events as possible, as interviews were limited to 60 minutes to minimize participant fatigue. In successive interviews, interviewers prioritized asking about events participants had not discussed in prior interviews. Hence, participants did not always discuss help-seeking in each of the interviews in which they reported recent help-seeking.

Data from these interviewers were in the form of notes interviewers typed into a computer using Computer Aided Telephone Interviewing (CATI) software while conducting the interview. Immediately afterwards, interviewers reviewed their notes while listening to the interview audio recording to improve the quality and quantity of the notes. Notes were reviewed for accuracy by the PIC study team. The notes were transferred to a qualitative software program (ATLAS.ti) to facilitate data management and analysis. The RAND institutional review board approved the study, and informed consent was obtained.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using grounded theory methodology, which employs thematic content and constant comparative methods to identify the range and salience of themes characterizing the phenomenon being studied.9 Interview notes were analyzed by one investigator (AI), a bilingual general internist, who marked text segments describing participants’ experiences with primary care help-seeking for depression, then grouped text segments with similar content into codes. The investigator then searched across codes for concepts that were shared or that linked codes together as themes.10 The investigator compared the text within and across participants to iteratively refine the set of themes identified. Text segments for codes and themes were compared with 3 other investigators familiar with the dataset – a psychologist (JM), an anthropologist (GR) and a psychiatrist (KBW) – in order to revise and refine defining features of each theme. Where themes appeared to have multiple components, they were broken into sub-themes to characterize the dimensions of the theme. Discordant views regarding the interpretation and sorting of concepts were resolved via consensus. The team finalized a codebook that defined the themes and subthemes, and the investigator (AI) re-coded the entire data set using the codebook.

Results

Characteristics of the analytic sample

Mean age was 64 ± 8 years (range: 50–88 years). Seventy-two percent was female, 55% was married, 36% had less than a high school education, 92% had health insurance, 89% completed both the second and the third qualitative interviews, and 67% was chronically depressed. Chronic depression was a created variable to summarize participants’ depression status over the 9 years after study enrollment, and was defined as having screened positive for depression on over half of the 6 PIC quantitative surveys conducted in that time. Among older Latino qualitative interview participants, no significant differences were found between participants who were in our analytic sample and those who were not (Appendix).

Emerging themes

As described, we analyzed participants’ narrative descriptions of recent experiences with a primary care visit (e.g., the context leading up to the visit, and the experience and/or outcomes of their visit) for mental health problems. We identified 5 themes: beliefs about the nature of depression; prior experiences with mental health disorders/treatments; sociocultural context (e.g., social relationships, being a caregiver, the media); clinic-related features (e.g., accessibility of providers, staff continuity, amount of visit time); and provider attributes (e.g., interpersonal skills, holistic care approach).

Beliefs about the nature of depression and its treatments

Participants who believed depression resulted from a chemical imbalance were open to using therapeutic treatments, even when it was difficult to accept needing a medication or counseling to feel better. A 61-year old woman said:

I’m not happy that my body just doesn’t want to behave itself and that I have to use medications to correct this. I used to hate that I had to depend on a medication to make me feel normal, but then I realized that I had an imbalance and I had to take care of it.

In contrast, participants who believed depression could not be controlled – regardless of available treatments and medical care – reported a lack of willingness to use depression treatments. A 54-year old woman shared:

You cannot control depression. Even if you discuss it with someone like a doc, by the time they finish medicating you and counseling you they didn’t cure it. It doesn’t stop. If you know that why put yourself through it?

Some believed depression was a condition that would take care of itself, or did not require medical treatment. “My depression will heal naturally,” said a 52-year old woman. A 54-year old woman described, “I just have to let the depression run its course.” Participants who believed they had to manage depression on their own described reticence or refusal to use therapeutic treatments. “Though my doctor suggested counseling, it’s up to me myself to get better. I have to do it on my own. I don’t need any medication,” said a 71-year old woman.

Participants who believed depression treatments were harmful or addicting reported treatment nonadherence. A 58-year old woman stated, “I was prescribed my medication to be taken twice a day but I only take it that way sometimes because I don’t want to get hooked on pills.” Participants also described antidepressant medications as unnatural or illicit substances; they referred to them as chemicals (“químicas”) and drugs (“drogas”).

Prior experiences with mental illness and its treatments

Participants’ willingness to seek care for mental health problems was negatively influenced by past experiences with a mentally ill family member. A 61-year old woman said, “My mother was a prescription addict, so I didn’t even want to take aspirin. But I came to realize there’s a difference between tranquilizers and the medications I take for depression.” A 54-year old woman reported, “Schizophrenia runs in the family and I don’t want to be in a looney-tooney bin. I can’t talk to nobody about it, no professionals, because they want to lock you up.”

“I’ve been taking them a long time. I don’t like to take them but they help,” said a 55-year old woman. Having experienced depression treatment benefit was associated with being aware and accepting the need to use depression treatment. A 57-year old woman stated, “I’ve tried to quite [my anti-depressant medication] twice by myself but my symptoms came back and I needed to go back on it. I know that if I stop taking it I will get sick and depressed and will be crying all the time.” In contrast, participants who previously experienced treatment side effects reported reluctance to re-start antidepressant medications. A 56-year old woman stated:

I used to take antidepressants years ago, but they made me have headaches and made me nervous. I generally felt worse throughout the day so I stopped taking them. I have no interest in getting antidepressants again.

Sociocultural context

Social relationships

Participants described that friends and family helped them access care for their mental health problems and gain insight into their depression, and encouraged participants to seek depression treatment. A 63-year old woman shared, “I didn’t initially want to go to the doctor for depression but my daughter convinced me. She said ‘You’d better go and I’ll take you’ so I said OK.” A 58-year old man said: “I never knew that people could sense my depression until my friend told me he noticed I was down. He told me not to be ashamed to tell the doctor how I’m feeling, so I told the doctor when I saw him.”

Care-giving role

Being a caregiver was described by some participants as affecting their ability to seek care for mental health problems. “I had to travel to Arizona to take care of my mother-in-law and make all the arrangements [for hospice],” said a 61-year old woman, who described that, for being out-of-state, she was unable to make an appointment to see her doctor to discuss the depressive symptoms she was experiencing. The participant went on to describe how she addressed her need by calling her doctor: “I talked to my doctor on the phone about how I was going to cope with the situation. My regular doctor is always there for me.”

The media

Participants who described receiving mental health information from diverse media sources – TV ads, newspaper articles, the Internet – reported asking their providers about their existing depression treatment or to start a new medication for their depressive symptoms. A 64-year old woman stated:

I asked my doctor about the seizure risk associated with Wellbutrin after seeing ads on the television. My doctor made me feel comfortable and helped me understand. I’m going with the doctor’s advice.

Information participants received from media sources was also associated with self-discontinuing their antidepressants despite their providers’ advice. “Even though my doctor prescribed Wellbutrin, I stopped taking it because I read something in the paper that it may give you seizures,” shared a 54-year old woman.

Clinic-related features

Availability and accessibility of providers

“It’s easy for me to meet with my doctor and to get appointments. He’s available,” said a 54-year old woman. Readily accessible providers enabled participants to seek care easily and promptly. “I called my doctor’s office to move the appointment up because I knew I had to get in there and talk to him right away about my depression,” said a 61-year old man.

Continuity of clinic staff

Having a consistent provider of care for mental health problems was associated with participant trust and satisfaction. “I’ve been with my current doctor for three years, and I trust him implicitly,” stated a 56-year old woman. A lack of provider continuity, however, was associated with frustration and reluctance to keep seeking care. “I never see the same person. I always have to start over with telling them about my depression. I almost feel like what for? Just to go through that all over again?” questioned a 54-year old man.

Amount of visit time

Participants who perceived that their providers had more time in the visit to spend with them described feeling more comfortable and willing to discuss their mental health problems. A 59-year old woman stated, “This was the first time I talked about my feelings with a doctor. I think this visit was different because the doctor gave me more time to talk about these things.” A 63-year old woman said, “It feels good to talk to him. Usually doctors are in a hurry - this doctor listens and he knows the feelings I have.” In contrast, participants whose providers did not have or take the time to talk with them felt reticent to discuss their mental health problems. “I didn’t talk to the doctor about my feelings because he’s always in a hurry and I didn’t feel like I could talk to him,” reported a 88-year old woman.

Provider-related attributes

Interpersonal skills

“Because my doctor understands me, I can talk to him about anything,” endorsed a 50-year old woman. Participants reported a willingness to talk openly about their depressive symptoms with providers they thought of as understanding. “My first impression of the doctor was hesitant because he was young. I thought, ‘What does he know?’ But he took great interest in me and really got to know my situation. I felt like he really cared about my symptoms,” stated a 67-year old man. Providers who displayed interest in understanding were described as helpful, attentive and concerned, even when they were of a different age or gender.

Participants described a range of communication skills – listening, asking questions, expressing support, providing encouragement – providers demonstrated and which were associated with participants’ willingness to listen and engage in depression treatment. “It was embarrassing to admit I had gone off my meds, but I felt encouraged when my doctor validated my feelings. I went back on my meds again as a result of my visit,” shared a 61-year old woman. Providers with good listening skills helped to relieve participants’ depressive symptoms and reduce the strain caused by their life stressors. “My doctor listens. Anyone who listens is helpful, especially to a person like myself. It relieves the stress of the situation that’s causing me to feel bad,” said a 55-year old man. Providers who expressed support and who followed up with participants about their depressive symptoms were described as attentive and responsive. A 61-year old woman reported, “Every time I go in my doctor asks me ‘How are you doing? Have you been crying?’ He’s always there for me. He checks in with me.” A 67-year old man stated, “The doctor said, ‘We’re going to get you better.’ Other guys just punch into the computer. My previous doctor was just typing things down and not really checking in with me.” Participants who felt their providers did not make an effort to listen and understand endorsed frustration. “You pay that money to go see them and they don’t listen to you. They are not walking around in your body, but they don’t listen to the person who’s experiencing it. That doesn’t make sense!” said a 54-year old woman.

A holistic approach to care

“I always feel good after seeing him. I like to see him because I can talk to him about health problems as well as other stuff going on in my family and can also talk to him about sports and leisure activities,” reported a 54-year old woman. Receiving care that addressed their physical health and emotional well-being – as well as the social activities in their lives – was associated with a positive help-seeking experience. These experiences were associated with open discussions about the stressors and positive events in participants’ lives, and were associated with participants feeling like their provider cared about them. A 65-year old woman described, “The doctor listened to me talk about the emotional problems I have been having. He seems interested in what is going on with me and how I am feeling, not just physically but also emotionally.”

Discussion

We employed unique qualitative data from the second stage of the PIC continuation study to describe older depressed Latinos’ salient experiences with primary care visits (e.g., the context leading up to their visit, and the experience and/or outcomes of their visit) for mental health problems 10 years after enrollment in a randomized controlled trial of quality improvement trial for depression in primary care. We identified 5 key themes: beliefs about the nature of depression; prior experiences with mental health disorders/treatments; sociocultural context; clinic-related features; and provider attributes. Our findings highlight the importance of social context, prior experiences with depression and its treatments, and the availability of understanding clinicians for shaping the experience of primary care visits for mental health problems in a sample of vulnerable older adults.

Distinctive results included the finding that caregiving was associated with difficulties accessing primary care for mental health problems. Prior work has evaluated the association of caregiving and depression outcomes among older adults.11 To our knowledge, our study is among the first to describe, using qualitative data, the effect of caregiving on seeking primary care for mental health problems in a sample of depressed older Latinos at long-term follow-up. Second, we found that the media was associated with participants’ encounters accessing and experiencing primary care for mental health problems at long-term follow-up. Participants described asking their provider to change or discontinue their current, sometimes longstanding, antidepressant medication in response to information from diverse media sources. Our work adds to a growing literature on the role of media and direct-to-consumer advertising on patient requests for antidepressant medication initiation and physician-prescribing behaviors.12 Studies have consistently shown that family history is a significant risk factor for depression.13 We found that past experiences with family members with mental illness were associated with recent experiences accessing and experiencing primary care for mental health problems at long-term follow-up.

Several of our findings are consistent with previously reported results on depressed patients at shorter-term follow-up, suggesting that some factors relevant to seeking primary care for depression in the short-term may continue to be relevant to older Latinos’ longer-term experiences with seeking care for depression. Similarly to our findings, prior studies have demonstrated that beliefs about depression and its treatments among older minorities can influence help-seeking behaviors for depression.14, 15 Provider attributes such as relational skills, which figured prominently in our findings, have been shown to be important to patients and may hinder or promote care-seeking for depression in primary care.16 Participants in our sample described with specific and rich detail salient provider interpersonal skills, and discussed how these attributes were associated with the experience and outcomes of their visit for mental health problems 10 years after PIC enrollment. That some factors relevant to seeking primary care for mental health problems at both

Our data, in being drawn from qualitative interviews conducted 10 years after enrollment in PIC, enabled us to describe participants’ encounters with seeking and experiencing primary care for mental health problems at longer-term follow-up than what previous studies have reported, which represents a significant study strength. A limitation of this data is that PIC study participants who were lost to follow-up over 10 years may differ from those who completed the qualitative interviews. Another potential limitation stems from the use of qualitative data from telephone interviewing. Telephone interviews may have minimized participant hesitation to talk about help-seeking for mental health problems, a potentially sensitive topic, but may have added to hesitation given the more impersonal nature of telephone calls compared to in-person interviews. Our sample’s experiences may differ from the experiences of older Latinos who are uninsured or who do not have access to or seek primary care for depression. We also acknowledge that Latinos are a heterogeneous group of individuals, and that important differences in help-seeking experiences by acculturation and Latino ethnic sub-group may have existed which we were unable to assess with our data.

We learned that a range of factors were associated with the context leading up to a recent primary care visit for mental health problems, and the experience and/or outcomes of that visit, among older depressed Latinos 10 years after PIC study enrollment. Our findings may have implications for primary care providers and the support of older depressed Latinos in patient-centered care for chronic depression.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Izquierdo was supported by a Diversity Supplement (NIMH Grant P30-MH082760-04), the UCLA Resource Centers for Minority Aging Research/Center for Health Improvement of Minority Elderly (RCMAR/CHIME) (NIH/NIA Grant P30-AG021684), and the UCLA-CTSI (NIH/NCRR/NCATS Grant UL1TR000124).

Appendix

Figure 1.

Flowchart of participants, from the qualitative interviews of the PIC continuation study to our study’s analytic sample

Table.

Sociodemographic characteristics of older Latino qualitative interview participants

| Variables | Overall (N=95) | Non-analytic sample (n=48) | Analytic sample (n=47) | Statistic | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean±SD, years | 60.6±8 | 60.3±7.8 | 60.9±8.3 | t[93] =0.3 | 0.735 |

| Female sex | 71 (74.7) | 37 (77.1) | 34 (72.3) | Chis[1] =0.3 | 0.595 |

| Married | 57(60.0) | 30 (62.5) | 27 (57.4) | Chis[1] =0.3 | 0.615 |

| Less than high school education | 34 (35.8) | 17 (35.4) | 17 (36.2) | Chis[1] =0 | 0.939 |

| Have health insurance | 83 (87.4) | 40 (83.3) | 43 (91.5) | Chis[1] =1.4 | 0.232 |

| Completed 2nd qualitative interview | 85 (89.5) | 43 (89.6) | 42 (89.4) | Chis[1] =0 | 0.972 |

| Completed 3rd qualitative interview | 85 (89.5) | 43 (89.6) | 42 (89.4) | Chis[1] =0 | 0.972 |

| Chronically depressed | 54 (58.7) | 24 (51.1) | 30 (66.7) | Chis[1] =2.3 | 0.129 |

Notes: SD = standard deviation. All values given are n (%) unless otherwise noted. A chi-squared statistic with 1 df was used for all variables except for age, for which an ANOVA t-test statistic was used.

References

- 1.Gallo JJ, Lebowitz BD. The epidemiology of common late-life mental disorders in the community: themes for the new century. Psychiatr Serv. 1999 Sep;50(9):1158–1166. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.9.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Callahan CM, Wolinsky FD, Stump TE, Nienaber NA, Hui SL, Tierney WM. Mortality, symptoms, and functional impairment in late-life depression. J Gen Intern Med. 1998 Nov;13(11):746–752. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00226.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pingitore D, Snowden L, Sansone RA, Klinkman M. Persons with depressive symptoms and the treatments they receive: a comparison of primary care physicians and psychiatrists. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2001;31(1):41–60. doi: 10.2190/6BUL-MWTQ-0M18-30GL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crystal S, Sambamoorthi U, Walkup JT, Akincigil A. Diagnosis and treatment of depression in the elderly medicare population: predictors, disparities, and trends. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003 Dec;51(12):1718–1728. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51555.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Callahan CM, Hui SL, Nienaber NA, Musick BS, Tierney WM. Longitudinal study of depression and health services use among elderly primary care patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994 Aug;42(8):833–838. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb06554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eaton WW, Shao H, Nestadt G, Lee HB, Bienvenu OJ, Zandi P. Population-based study of first onset and chronicity in major depressive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008 May;65(5):513–520. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.5.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams N, Simpson AN, Simpson K, Nahas Z. Relapse rates with long-term antidepressant drug therapy: a meta-analysis. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2009;24(5):401. doi: 10.1002/hup.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wells KB, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, et al. Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2000 Jan 12;283(2):212–220. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.2.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: grounded theory procedures and techniques. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernard HR, Ryan GW. Analyzing qualitative data: systematic approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson A, Fan MY, Unutzer J, Katon W. One extra month of depression: the effects of caregiving on depression outcomes in the IMPACT trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008 May;23(5):511–516. doi: 10.1002/gps.1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kravitz RL, Epstein RM, Feldman MD, et al. Influence of patients’ requests for direct-to-consumer advertised antidepressants: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2005 Apr 27;293(16):1995–2002. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.16.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klein DN. Symptom criteria and family history in major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1990 Jul;147(7):850–854. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.7.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper-Patrick L, Powe NR, Jenckes MW, Gonzales JJ, Levine DM, Ford DE. Identification of patient attitudes and preferences regarding treatment of depression. J Gen Intern Med. 1997 Jul;12(7):431–438. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00075.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sussman LK, Robins LN, Earls F. Treatment-seeking for depression by black and white Americans. Soc Sci Med. 1987;24(3):187–196. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(87)90046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kravitz RL, Paterniti DA, Epstein RM, et al. Relational barriers to depression help-seeking in primary care. Patient Educ Couns. Feb;82(2):207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]