Abstract

Spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) is a rare cause of acute coronary syndrome. It occurs predominantly among younger females and typically in the absence of atherosclerotic coronary artery disease. It is associated with peripartum period, connective tissue disorders, vasculitides, and extreme exertion. Presentations vary greatly, and this condition can be fatal. Given its rarity, there are no guidelines for management of SCAD. We present the cases of two female patients, with no coronary artery disease risk factors or recent pregnancy, who were presented with non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), respectively, secondary to SCAD. Both had excellent outcome after emergent percutaneous intervention. Our first patient was presented with NSTEMI with ongoing chest pain and dynamic electrocardiogram (ECG). Emergent left heart catheterization was significant for first obtuse marginal (OM1) dissection, confirmed by optical coherence tomography. Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with two bare metal stents was performed with resolution of symptoms and ECG changes. The second patient is known to have syndrome, presented with STEMI and emergent coronary angiography showed left anterior descending dissection with intramural hematoma confirmed by intravascular ultrasound and treated with a drug-eluting stent with resolution of symptoms and ST changes. Her hospital course was complicated by post–myocardial infarction pericarditis that was improved with colchicine. Both the patients were observed in the coronary care unit for 24 hours. Both remained asymptomatic at 6-month follow-up. SCAD is a rare cause of acute coronary syndrome. In patients with early presentation, limited disease, and ongoing symptoms, emergent cardiac catheterization with percutaneous intervention has excellent outcome. More studies are needed to establish evidence-based management guidelines.

Keywords: dissection, PCI, myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndrome

Spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) is a rare cause of acute coronary syndrome. It occurs predominantly among younger females and typically in the absence of atherosclerotic coronary artery disease. It is associated with peripartum period, connective tissue disorders, vasculitides, and extreme exertion. Presentation varies greatly from being completely asymptomatic to cardiogenic shock and even sudden cardiac death. There are no guidelines for treatment as it is a rare condition. We will discuss the cases of two female patients, with no coronary artery disease risk factors or recent pregnancy, who were presented with non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) secondary to SCAD. Both had excellent outcome after emergent percutaneous intervention.

Case Presentation

First Case

A 42-year-old nonpregnant female patient with medical history of seizure disorder and depression was presented to our emergency department with chest pain of 2-hour duration. The pain was substernal, nonradiating, and associated with nausea, vomiting, and diaphoresis. It improved after three tablets of sublingual nitroglycerine. Physical examination was unremarkable and vital signs were within normal limits. Her ECG showed T-wave inversion and ST segment depression in leads V3–V6. Initial evaluation including complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, liver function test, and the first set of cardiac enzymes was unremarkable. The patient was admitted to the cardiology floor and started on medical treatment for acute coronary syndrome. Six hours later, she developed persistent severe chest pain, her blood pressure dropped to 69/33 mm Hg with new ECG progression with T-wave inversion in leads I and aVL. Troponin I, creatinine kinase-MB (CKMB), and CKMB index were elevated at 1.73 ng/mL, 20.7 ng/mL, and 8.2%, respectively. Given, her hemodynamic instability, ongoing chest pain, elevated cardiac enzymes, and dynamic ECG changes, the patient was transferred to the cardiac care unit and emergent coronary angiogram was performed. It was significant for dissection of the first obtuse marginal (OM1) branch of the left circumflex artery that extended distally with severe stenosis and thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) III flow, normal left main artery, left anterior descending artery, and right coronary artery (Figs. 1 and 2). Optical coherence tomography (OCT) showed a large false lumen compressing the true lumen of the artery (Fig. 3). Because of ongoing chest pain, PCI of OM1 was performed with two bare metal stents resulting in coronary blood flow restoration (Fig. 4) and complete resolution of her chest pain and ECG changes. Distal small OM1 dissection was also present, but it was clinically insignificant given the resolution of symptoms and ECG changes. The next day, the patient was doing well and was free of chest pain. Transthoracic echo showed normal left and right ventricular systolic function with mild hypokinesis of distal inferolateral and apical segments, normal ejection fraction, and no pericardial effusion. The patient was transferred to the floor and later on discharged home on medical management for coronary artery disease. At 9-month follow-up, she was completely asymptomatic and denied any complaints.

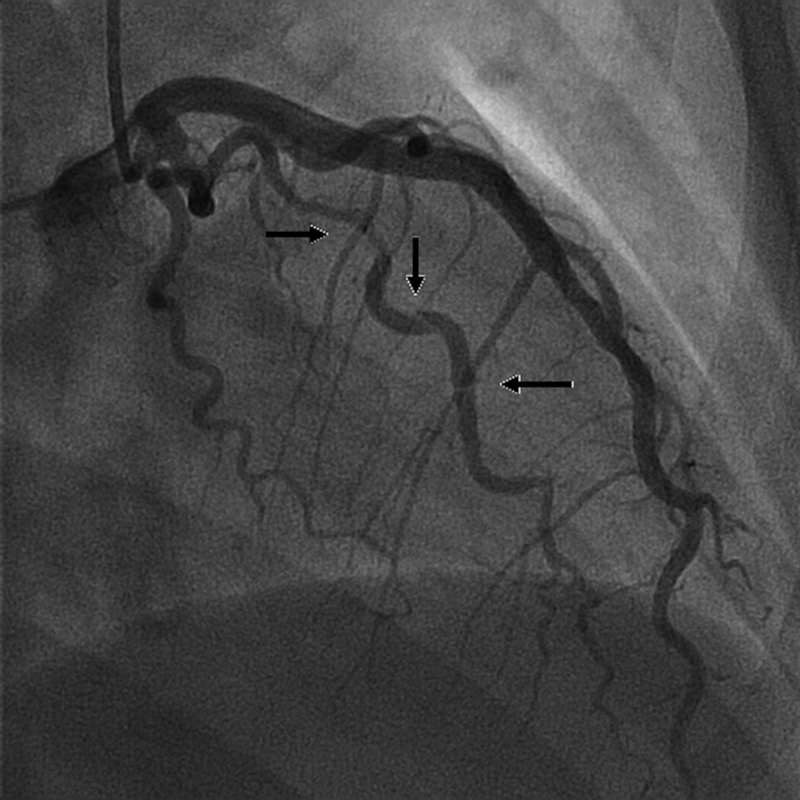

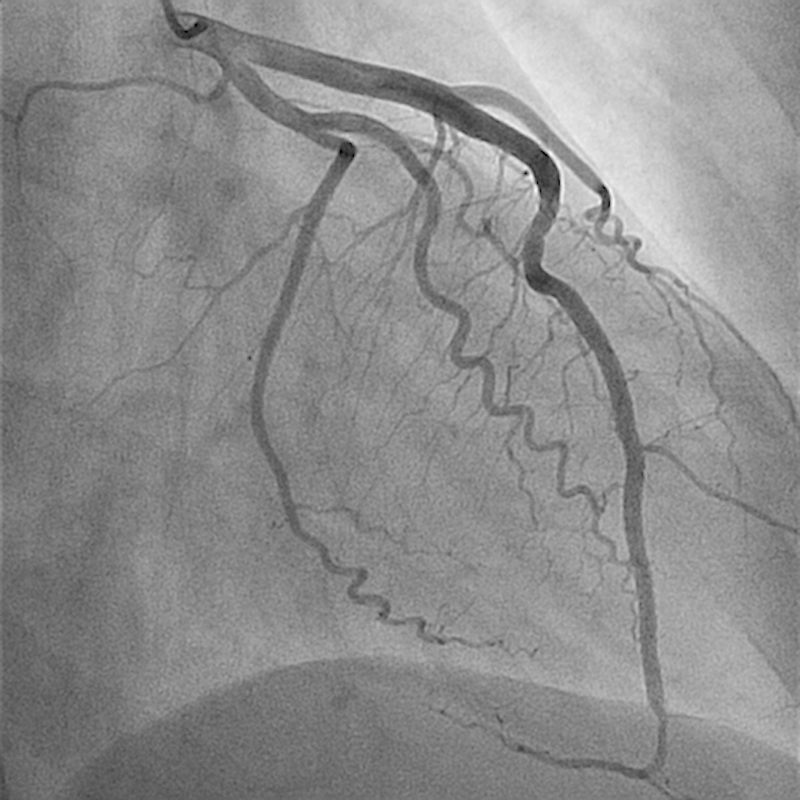

Fig. 1.

Dissection (arrows) of the first obtuse marginal branch of the left circumflex artery that extended distally.

Fig. 2.

No flow in first obtuse marginal upon advancing the wire.

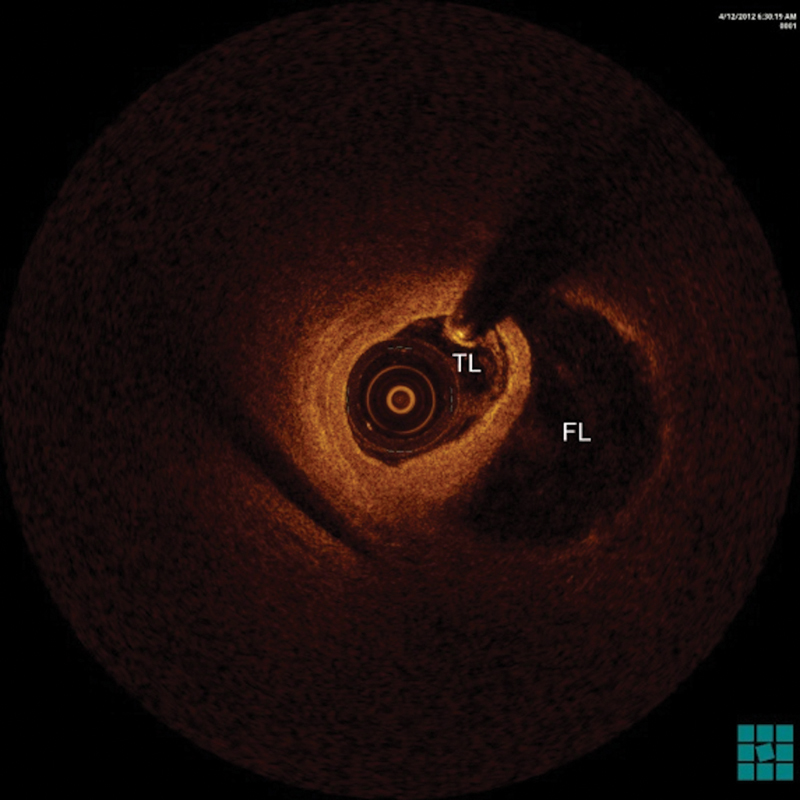

Fig. 3.

Optical coherence tomography showed a large false lumen (FL) compressing the true lumen (TL) of the dissected artery.

Fig. 4.

Normal flow in first obtuse marginal (OM1) after PCI. Seen also is insignificant distal OM1 dissection.

Second Case

A 37-year-old female patient with history of Sjögren syndrome and on hydroxychloroquine, presented to the emergency department with acute substernal chest pain, was associated with diaphoresis and bilateral hand numbness. ECG showed ST elevation in anterolateral and inferior leads. The cardiac catheterization laboratory was activated immediately. Her Troponin I was elevated at 0.191 ng/mL. Emergent coronary angiography showed distal LAD diffuse 99% occlusion with TIMI I flow (Fig. 5). It also showed large LAD that wraps around the apex and supplies the inferior wall (Fig. 5). Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) confirmed the presence of dissection with intramural hematoma and absence of atherosclerosis in distal LAD (Fig. 6). The patient was treated with a drug-eluting stent with restoration of flow (TIMI III) (Fig. 7) and resolution of chest pain and ST elevation. She was admitted to the cardiac care unit for close observation. The following day, she developed intermittent pleuritic chest pain and new ST elevation in inferior, anterior, and lateral leads. She was taken to the cardiac catheterization laboratory where coronary angiogram showed patent stent and no obstructive lesions. Transthoracic echocardiography showed ejection fraction of 40 to 45% with severe hypokinesis of apical, apical septal, apical anterior, and apical lateral segments. She was started on colchicine for post-MI pericarditis treatment with significant symptomatic improvement. The patient was transferred to the floor later on. A complete autoimmune inflammatory workup including ANA by IFA, Ds DNA, RNP antibody, smith antibody, anti-CCP, SSA/SSB antibodies, anticardiolipin antibodies, anti-β2 glycoprotein I IGG and IGM antibodies, rheumatoid factor were negative. Her ESR, CRP, C3 and C4 levels were also within normal limits. Given her negative rheumatological panel, coronary vasculitis was unlikely. She was discharged on medical management for coronary artery disease. In 9-month follow-up, the patient reported no recurrence of the chest pain and denied any other cardiac symptoms.

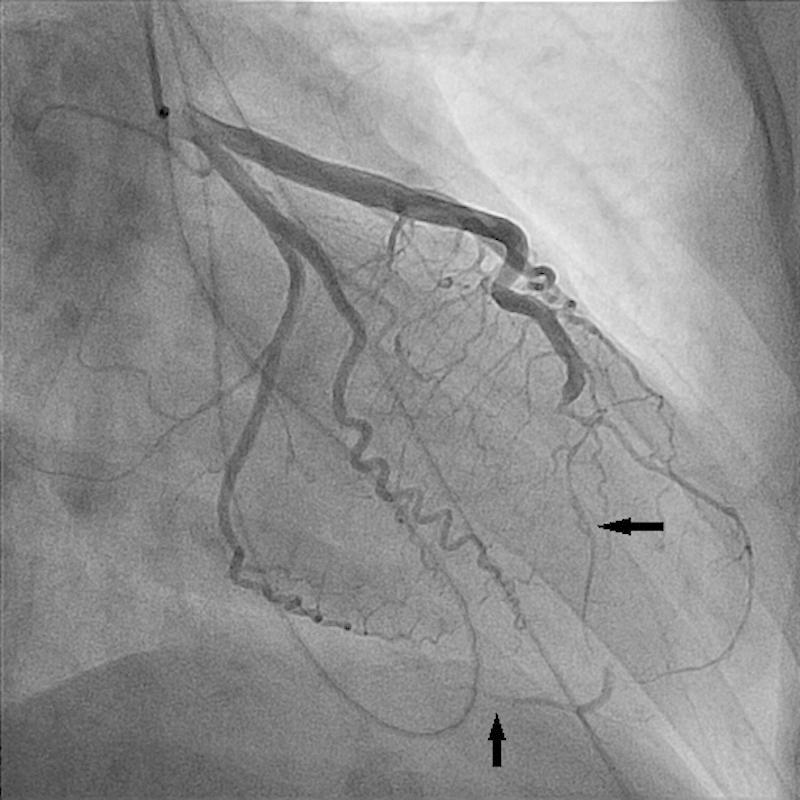

Fig. 5.

Severe LAD stenosis secondary to intramural hematoma (horizontal arrow). Also seen is the large LAD that wraps around the apex and supplies the inferior wall (vertical arrow).

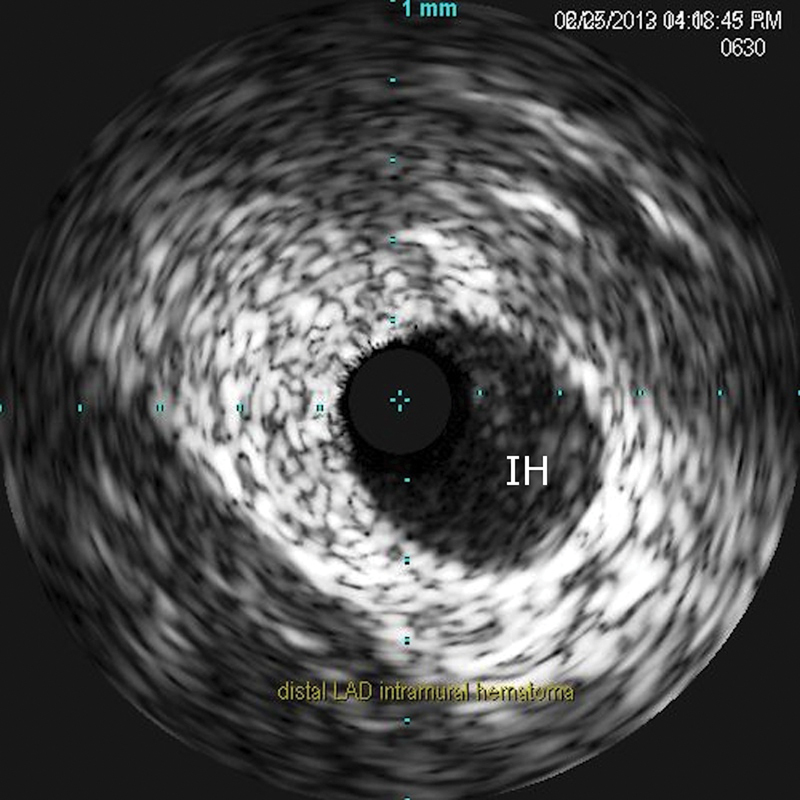

Fig. 6.

Intravascular ultrasound showed intramural hematoma (IH) of distal LAD.

Fig. 7.

Restoration of flow in LAD post-PCI.

Discussion

SCAD is a rare cause of acute coronary syndrome. The first case was described in 1931.1 Its incidence among cases of acute coronary syndrome is 0.2% in angiographic studies2 3 and 0.5% after autopsy in patients who had sudden cardiac death.4 SCAD is more frequently diagnosed in the left coronary artery, with a female-to-male ratio of 2:1.2

Most cases of SCAD occur in female patients during pregnancy or postpartum period. A subtype of SCAD is associated with connective tissue diseases like Marfan syndrome, Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, several autoimmune diseases (Kawasaki, systemic lupus erythematosus, and rheumatoid arthritis) and fibromuscular dysplasia of the coronaries or other vessels.3 5 SCAD associated with atherosclerosis, intense exercise, cocaine abuse, and cyclosporine and female hormonal treatments such as oral contraceptives has been also reported. Rarely, it can occur in asymptomatic women with few or no risk factors for coronary artery disease.4 Interestingly, both patients we presented had SCAD with no identifiable predictor or acquired or hereditary risk factors.

Coronary artery dissection is characterized by separation of the layers of the arterial wall. This results in a false lumen or an intramural hematoma between the intima and the media or the media and the external elastic lamina, causing compression of the true lumen of the artery6 and resulting in myocardial ischemia. To be classified as spontaneous, dissection must occur in the absence of trauma, previous surgery or catheterization, or an extension of aortic dissection. While the left anterior descending artery is the most commonly affected artery in females, right coronary artery tends to be more frequently involved in male patients.7 Of note is the unusual site of dissection in our first case, which involved the OM1 branch of the left circumflex artery.

The pathogenesis of SCAD is not yet fully understood.2 The initial event that leads to dissection is not clear, and no single factor has been found to be causative.1 8 Proposed mechanisms pertain to changes in vascular wall properties that lead to weakening of the media and arterial wall connective tissue. These include changes in smooth muscle cell metabolism, the effect of proteases released from eosinophilic infiltrates, and pregnancy-related connective tissue changes.9

The clinical presentation of SCAD varies, and depending on the number of involved arteries, extent of involvement and rate of progression ranges from a completely asymptomatic state to acute coronary syndrome, cardiogenic shock, and sudden cardiac death.10 Our first case was presented with NSTEMI and the second case was presented with STEMI. Both cases had ongoing chest pain, abnormal ECG, and elevated cardiac enzymes necessitating urgent coronary angiogram.

Percutaneous coronary angiography is the primary diagnostic modality for SCAD. The use of intracoronary imaging with IVUS or OCT provides more detailed morphological information of the lesion and dissection planes in the arterial wall.11 It is important to keep in mind that intubation of the coronary ostium and contrast injection in patients suspected to have SCAD can be potentially dangerous, as forceful maneuvers during coronary angiography may lead to propagation of the dissection.

Because of its rarity, there are no randomized clinical trials or consensus in regard to SCAD management.6 Most of the literature consists of case reports and some case series. Furthermore, many reported cases have been diagnosed postmortem after sudden cardiac deaths.12

Conservative or medical management including anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy of patients with SCAD is a possible treatment strategy in stable patients. β-blockers might be beneficial by reducing contractility and shear stress on the affected vessel, thus, preventing expansion of the lesion.13 PCI and stenting is the preferred strategy in situations of ongoing ischemia or infarction with limited disease and early presentation after identification of the true lumen and false lumen.11 14 15 Advancing the guide wire may be challenging, and it may lead to expansion of the lesion or perforation of the coronary artery if it was advanced through the false lumen. After confirming the site of the guide wire, stent placement must start distally in the nondissected part of the vessel, and it must continue proximally to prevent distal expansion of the lesion or propagation of the intramural hematoma.13

Cases with multivessel involvement, left main coronary artery dissection, or failed PCI may need to be treated by coronary artery bypass graft. Fibrinolysis is not recommended because of the increased risk of bleeding.8 In our first patient, ongoing symptoms, hemodynamic instability and the evidence of progressive myocardial ischemia were the key factors in making the decision to proceed PCI and stent placement. While in the second patient with STEMI and near total occlusion of the LAD necessitated emergent cardiac catheterization and PCI.

Patients treated for SCAD should be closely monitored in an inpatient setting, preferably in the coronary care unit. If symptoms reoccur or the patient continues to have chest pain, coronary blood flow may be evaluated by conventional or CT coronary angiography. If the dissection is located in the proximal segment of the coronary arteries, follow-up by CT angiography of the coronaries rather than coronary angiography is advised, to avoid the risk of further propagation of the dissection.13 After a primary SCAD event, the 10-year SCAD recurrence rate was reported to be as high as 29%. Median time to second episode ranges between few days to more than 10 years. The recurrence can occur in previously unaffected coronary artery.5

Conclusion

SCAD is a rare cause of acute coronary syndrome, more common in female patients with no or few risk factors for coronary artery disease. It can also be seen in connective tissue disease, pregnancy/postpartum period and association with some medications. Treatment of this condition should be individualized to patients depending on the clinical presentation, location, severity of the disease, and associated risk factors and comorbidities. We report two cases of SCAD in young women with no CAD risk factors or recent pregnancy, presented with NSTEMI and STEMI, respectively. The diagnosis was made by coronary angiography and OCT or IVUS. Both patients were treated promptly with emergent PCI and had excellent outcome. As more cases of this rare entity are reported, we believe that will help to establish a better understanding of the best management options for individual patients.

References

- 1.Pretty H C. Dissecting aneurysm of coronary artery in a woman aged 42. BMJ. 1931;1:667. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verma P K, Sandhu M S, Mittal B R. et al. Large spontaneous coronary artery dissections-a study of three cases, literature review, and possible therapeutic strategies. Angiology. 2004;55(3):309–318. doi: 10.1177/000331970405500311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azzarelli S, Fiscella D, Amico F, Giacoppo M, Argentino V, Fiscella A. Multivessel spontaneous coronary artery dissection in a postpartum woman treated with multiple drug-eluting stents. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2009;10(4):340–343. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0b013e3283276dee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sherrid M V, Mieres J, Mogtader A, Menezes N, Steinberg G. Onset during exercise of spontaneous coronary artery dissection and sudden death. Occurrence in a trained athlete: case report and review of prior cases. Chest. 1995;108(1):284–287. doi: 10.1378/chest.108.1.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tweet M S, Hayes S N, Pitta S R. et al. Clinical features, management, and prognosis of spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Circulation. 2012;126(5):579–588. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.105718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Auer J, Punzengruber C, Berent R. et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection involving the left main stem: assessment by intravascular ultrasound. Heart. 2004;90(7):e39. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2004.035659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jorgensen M B, Aharonian V, Mansukhani P, Mahrer P R. Spontaneous coronary dissection: a cluster of cases with this rare finding. Am Heart J. 1994;127(5):1382–1387. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(94)90060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butler R, Webster M WI, Davies G. et al. Spontaneous dissection of native coronary arteries. Heart. 2005;91(2):223–224. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2003.014423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klein J. Hakimian j, Makaryus A. Spontaneous Right Coronary Artery dissection. Tex Heart Inst J. 2012;39(1):95–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheung S, Mithani V, Watson R M. Healing of spontaneous coronary dissection in the context of glycoprotein IIB/IIIA inhibitor therapy: a case report. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2000;51(1):95–100. doi: 10.1002/1522-726x(200009)51:1<95::aid-ccd22>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmid J, Auer J. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection in a young man - case report. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;6:22. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-6-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Juszczyk M, Marnejon T, Hoffman D A. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection postpartum. J Invasive Cardiol. 2004;16(9):524–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wain-Hobson J, Roule V, Dahdouh Z, Sabatier R, Lognoné T, Grollier G. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: one entity with several therapeutic options. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2012;13(3):e1–e4. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Missouris C G, Ring A, Ward D. A young woman with chest pain. Heart. 2000;84(6):E12. doi: 10.1136/heart.84.6.e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roig S, Gómez J A, Fiol M. et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection causing acute coronary syndrome: an early diagnosis implies a good prognosis. Am J Emerg Med. 2003;21(7):549–551. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]