Abstract

We present the case of a 65-year-old man with an atypical presentation of pulmonary embolism (PE) as ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) with high troponin. He presented with acute exertional dyspnoea without chest pain. Since the initial ECG showed ST elevation anteroseptal (V1–V4) with concomitant deep Q waves, a delayed STEMI with probable left ventricular aneurysm was the working diagnosis and was treated accordingly. Nevertheless, his coronary angiography was normal and it was then that PE was suspected. D-dimer was found to be elevated and CT pulmonary angiography confirmed bilateral PE with a large thrombus within the right main pulmonary artery. The patient made good clinical recovery and his ST elevation resolved with anticoagulation. The source was found to be a deep vein thrombosis in his right leg. The treatment was not compromised by the delayed diagnosis as he received timely anticoagulation as part of STEMI management.

Background

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a common acute medical emergency yet the diagnosis can be often challenging. It is associated with many ECG findings, most of which are non-specific. Symptoms and signs of PE frequently overlap with other acute cardiopulmonary syndromes, making it difficult to make a quick and correct diagnosis. ECG is one of the first supplementary examinations to be performed in cases of suspected PE, and ECG abnormalities can be seen in 80 to 90% of patients, varying from the typical S1Q3T3 pattern to non-specific ST segment depression or T-wave changes.1 ST elevation anteroseptal with acute PE is a rare finding and is previously well reported, however, in clinical practice it is always only considered after negative cardiac investigations. Our case emphasises the importance of maintaining an open mind to cardiopulmonary causes of ST elevation other than myocardial ischaemia in acute medical presentations.2

Case presentation

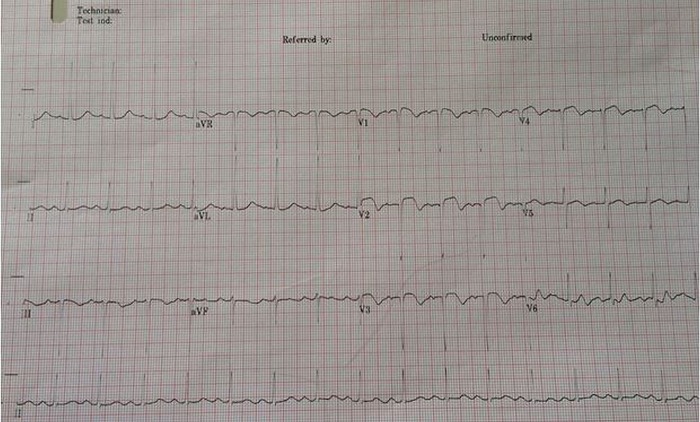

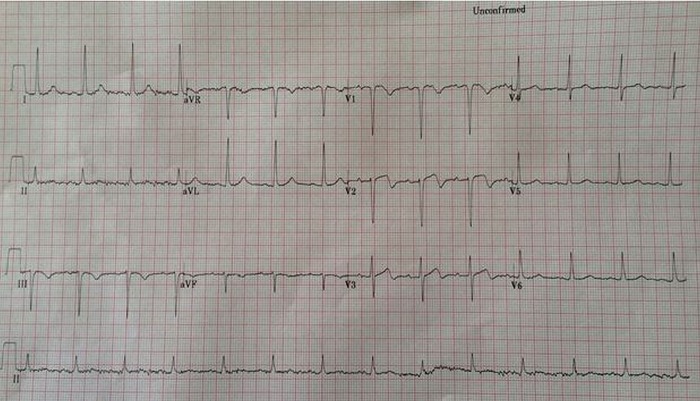

We present the case of a 65-year-old adult man who presented with a history of progressive dyspnoea on exertion for 1 week. On the day of admission, he had a presyncope at home and called the ambulance. He experienced no chest pain, fever, cough or lower limb swelling. He had a history of morbid obesity, for which he underwent a successful gastric bypass surgery 1 year before presentation resulting in an eight stone weight loss. In addition, he had a history of depression and alcohol dependence of around 40 unit's weekly. He had no history of other cardiac risk factors aside from obesity and his father died in his 5th decade from an acute coronary syndrome. The patient was a non-smoker. Initial observations at an emergency department showed blood pressure of 123/87, regular pulse of 103/min, respiratory rate of 22/min and 92% room air oxygen saturation. The ECG showed anteroseptal ST elevation with Q waves in V1–V4 but with no reciprocal ST changes (figure 1). Clinical examination revealed normal heart and chest sounds with normovolaemia and central obesity, but no further clinical signs. Initially, the patient felt prompt relief with oxygen and remained haemodynamically stable all through his hospital admission. He was initially taken to the coronary care unit following an initial consultation with the cardiologist, who suggested the unlikelihood of an acute STEMI given the delayed presentation and the development of Q waves, but he would still need urgent coronary angiogram instead of emergency percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in addition to cardiac echocardiography to eliminate the possibility of left ventricular aneurysm or Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. The absence of a wide mediastinum, pneumothorax or massive cardiomegaly on the chest X-ray (CXR) had essentially ruled out many of the other life-threatening causes of acute ST elevation (eg, aortic dissection and cardiac tamponade). The patient underwent coronary angiography 72 h later, which showed a completely patent coronary bed. It was at this stage that pulmonary instead of coronary thrombosis was considered a possibility given the fact that his dyspnoea was ongoing. D-dimer was elevated and the CT pulmonary angiography confirmed bilateral PE. From day 5 of admission onward the patient began to feel better and made a full clinical recovery. His O2 saturation returned to normal with no added oxygen requirement. The ST elevation resolved following anticoagulation (figure 2). He was discharged home on novel anticoagulant (rivaroxaban) taking into account his history of alcohol use and the possible interactions with warfarin. He was to be anticoagulated for 6 months.

Figure 1.

Initial ECG shows ST elevation V1–4 with concomitant deep Q waves.

Figure 2.

ECG 5 days following anticoagulation with the resolution of the ST elevation.

Investigations

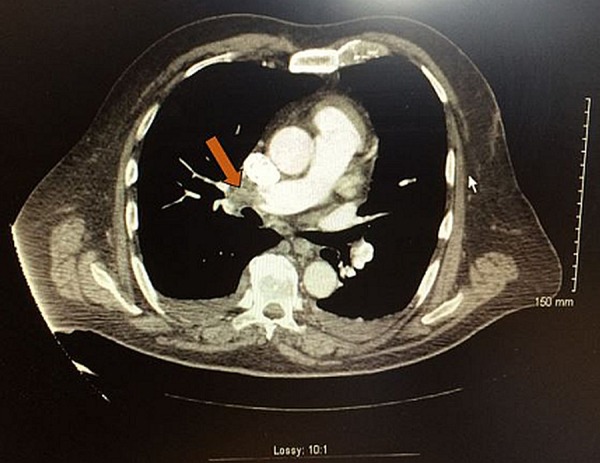

The patient's blood tests showed high troponin-T of 179 ng/L (local laboratory reference 0–14), high aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase at 171 and 131 U/L, respectively. C reactive protein (CRP) was also elevated at 22.2 mg/dL (local reference 0–0.5). The remainder of his blood tests were normal. His CXR showed mild cardiomegaly but were otherwise unremarkable. His echocardiography (figure 3) showed surprisingly normal size and function of the right ventricle with estimated right ventricular systolic pressure of 27.95 mm Hg and without evidence of left ventricular cardiomyopathy, thrombus or aneurysm. Following the normal coronary angiogram, his D-dimer was found to be significantly raised at 5000 ng/L (0–245) and this was followed by the CT pulmonary angiogram confirming large thrombus within the right main pulmonary artery (figure 4), and involving the proximal right upper, middle and lower lobe branches in addition to considerable amount of thrombus within second order left upper and lower lobe branches. Bi-basal atelectasis with effusions were also noted, larger on the left. Doppler ultrasound of his lower limbs revealed a non-occlusive thrombus in the superficial femoral vein and common femoral vein on the right leg. His troponin and CRP levels came down eventually and his liver enzymes normalised on day 5.

Figure 3.

Normal subcostal four-chamber view on the echocardiography.

Figure 4.

CT pulmonary angiography revealing large thrombus within the main right pulmonary artery (arrowhead).

Treatment

The patient initially received a loading dose of dual antiplatelet (aspirin and clopidogrel) for the presumed STEMI, sublingual nitrates, β-blocker, statin and oxygen. Following the normal coronary angiogram, clopidogrel was stopped, but he was kept on low-molecular-weight heparin pending his CT pulmonary angiogram, which was subsequently switched to novel oral anticoagulant (rivaroxaban).

Outcome/follow-up

The patient was discharged 2 weeks following admission on oral anticoagulation (rivaroxaban) for 6 months.

Discussion

Variable ECG findings reported in association with PE included alterations in rate, rhythm, conduction, axis and morphology with sinus tachycardia being the most common abnormality. The online literature described many examples of similar presentation.1 3 4 The mechanism for the accompanying ECG changes is usually right ventricular strain secondary to increased pressure within the right side leading to unmatched high oxygen demand, but other accounts exist in the literature including paradoxical embolisation leading to coronary occlusion.5 Microvascular coronary vasospasm induced by sudden right ventricular strain or hypoxaemia-induced catecholamine surge are other explanations for the ST elevation.6 Most of the reported cases in the literature showed evidence of right ventricular abnormalities during the echocardiogram examination, but our case did not and the possible explanation for this would be the fact that the echocardiography was delayed for 48 h and the transient right ventricular overload would have been resolved by then. The rise in troponin in acute PE is increasingly recognised by clinicians and being elevated in our case is considered typical.7

Learning points.

ST elevation is not always myocardial infarction.

Acute pulmonary embolism overlaps with other cardiopulmonary syndromes and a high index of suspicion should be adopted in such presentations.

ST elevation represents a diagnostic challenge in many presentations and should be interpreted after considering other clinical data and diagnostics before making a final diagnosis.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Khalid Elguzoli for his effort in data collection.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Zhang F, Qian J, Dong L et al. . Multiple ST-segment elevations in anterior and inferior leads: an unusual electrocardiographic manifestation in acute pulmonary embolism. Int J Cardiol 2012;160:e18–20 (cited 2014 October 19). http://www.internationaljournalofcardiology.com/article/S0167527311023126/fulltext [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang K, Asinger R, Marriott H. ST-segment elevation in conditions other than acute myocardial infarction. New Engl J 2003;2128–35 (cited 2014 October 19). http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMra022580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goslar T, Podbregar M. Acute ECG ST-segment elevation mimicking myocardial infarction in a patient with pulmonary embolism. Cardiovasc Ultrasound 2010;8:50 (cited 2014 October 19). http://www.cardiovascularultrasound.com/content/8/1/50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falterman TJ, Martinez JA, Daberkow D et al. . Pulmonary embolism with st segment elevation in leads v1 to v4: case report and review of the literature regarding electrocardiographic changes in acute pulmonary embolism. J Emerg Med 2001;21:255–61 (cited 2014 October 19). http://www.jem-journal.com/article/S073646790100381X/fulltext [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng TO. Mechanism of ST-elevation in precordial leads V(1)-V(4) in acute pulmonary embolism. Int J Cardiol 2009;136:251–2 (cited 2014 October 19). http://www.internationaljournalofcardiology.com/article/S0167527309000965/fulltext [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohsen A, El-Kersh K. Variable ECG findings associated with pulmonary embolism. BMJ Case Rep 2013;2013:pii: bcr2013008697 (cited 2014 October 19). http://casereports.bmj.com/content/2013/bcr-2013–008697.full [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ng ACC, Yong ASC, Chow V et al. . Cardiac troponin-T and the prediction of acute and long-term mortality after acute pulmonary embolism. Int J Cardiol 2013;165:126–33 (cited 2014 November 2). http://www.internationaljournalofcardiology.com/article/S0167527311008254/fulltext [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]