Abstract

Hydroa vacciniforme is one of the rarest forms of photosensitivity disorders of the skin. Effective treatment options are scarce and mainly constitute of strict sun protection. Lately, hydroa vacciniforme has been associated with Epstein-Barr virus infection. We present a patient with hydroa vacciniforme and concomitant previous/chronic Epstein-Barr virus infection. In this case, antiviral treatment was successful.

Background

Hydroa vacciniforme (HV) is an extremely rare photosensitivity dermatosis first described by Bazin in 1862. The disorder is characterised by acute, necrotic papulovesicular eruptions following sun exposure. The eruptions later become umbilicated and heal with depressed vacciniform (pox-like) scars. The lesions are symmetrically localised and typically affect the nose, cheeks, ears and back of the hands. Skin eruptions can appear throughout the year, but obviously, they are more frequent and often worse during the spring and summer months.

HV predominantly affects children and typically regresses spontaneously by early adulthood. The disease tends to run a longer course in male than in female patients.1 HV is most frequently sporadic though a few familial cases have been reported.2 3

In recent years a definite association to Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection has been demonstrated.4–7 We present a patient with typical HV and elevated serum levels of EBV-DNA copies treated successfully with acyclovir and valacyclovir.

Case presentation

A 6-year-old boy was referred to our outpatient clinic due to a history of recurrent papulovesicular skin lesions on sun-exposed areas (figure 1). The symptoms started during springtime just before his fifth birthday. He also suffered from periodic red eyes and easy bleeding from his gums, but was otherwise healthy. No obvious infection preceded the onset of our patient's symptoms.

Figure 1.

Photographs over the years demonstrating vesicles and scarring. In the photographs, the patient is 10, 11 and 14 years of age (read from left to right).

Investigations

Test results for routine laboratory parameters were normal apart from a slight leukocytosis initially. Antinuclear antibody, SS-A (Ro) antibody and SS-B (La) antibody tests were negative and the porphyrins were normal.

Phototesting showed normal minimal erythemal dose for ultraviolet A (UVA; <35 J/cm2) and ultraviolet B (UVB; <0.15 J/cm2) radiation. Photoprovocation induced vesiculobullous lesions in the skin area subjected to UVA radiation (35 J/cm2 daily) and a distinct erythema in the skin area subjected to UVB radiation (0.15 J/cm2 daily) after the second day of provocation (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Skin reactions on the second day of the photoprovocation. The photograph shows distinct erythema in the skin area subjected to ultraviolet (UV) B (UVB) radiation (top square) and vesiculobullous lesions in the skin area subjected to UVA radiation (bottom square).

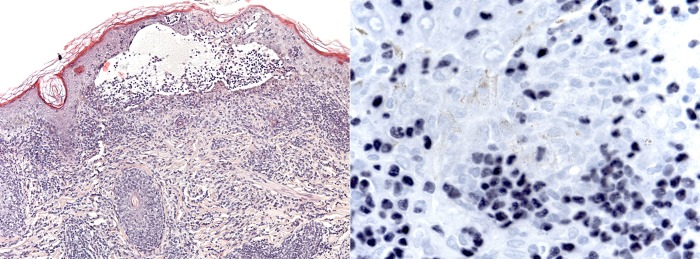

Histological examination of a skin biopsy demonstrated epidermal necrosis and a dense, diffuse infiltrate of not atypical lymphocytes of which more than half showed EBV positivity (Epstein-Barr encoding region (EBER) in situ hybridisation; figure 3). The infiltrate was dominated by T cells, and contained hardly any B cells. There was an almost equal amount of CD4+ and CD8+ cells, whereas only a few scattered CD56+ cells were seen. Staining for CD30 was negative. Molecular analysis demonstrated monoclonal rearrangement of T-cell receptor (TCR) γ and TCR-δ genes. Quantitative PCR analysis for EBV-DNA in serum was performed showing 436 862 EBV copies/mL. EBV serology gave positive result for Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen (EBNA) IgG when examined at the age of 10 in accordance with previous/chronic infection.

Figure 3.

Reticular degeneration of keratinocytes with intraepidermal vesiculation. The vesicles contain fibrin and inflammatory cells, mostly lymphocytes and polymorphonuclear leukocytes. There is a dense, diffuse infiltrate in the dermis of mature, small lymphocytes, unsuspicious of neoplasia. In situ hybridisation of the Epstein-Barr virus encoding region shows positivity in 50% of the lymphocytes (photograph to the right).

Clinical examinations at the first visit and during follow-up did not reveal lymphadenopathy or organomegaly, nor have repeated evaluations with blood smear and flow cytometry shown signs of lymphoproliferative disease. No increase of CD56+ lymphocytes was seen in the peripheral blood.

Differential diagnosis

Our primary differential diagnoses included HV, juvenile spring eruption, polymorphic light eruption, actinic prurigo and erythropoietic protoporphyria.

Treatment

On the basis of the patient history, the clinical picture and the results of the photoprovocation tests the patient was diagnosed with HV. Initial therapy consisted of strict sun protection (topical sun blocker and seeking shadow) and fish oil supplements (five capsules daily). At the age of 10, treatments with calcium and vitamin D supplements were added due to biochemical signs of vitamin D deficiency.

Owing to unsatisfactory therapeutic effect of the fish oil supplements, new treatment strategies were sought. Based on the results of the quantitative PCR analysis for EBV-DNA in serum and on the results of the histological examination of the skin biopsy alongside case reports of a potential benefit of antiviral treatment, treatment with acyclovir 400 mg twice daily (approximately 50 mg/kg/day) was initiated at the age of 11. The therapy was changed to valacyclovir 500 mg twice daily after 2 years to improve bioavailability.

Outcome and follow-up

During the treatment with oral antiviral drugs our patient has had fewer and milder skin eruptions. However, it should be noted that the treatment adherence intermittently has been very poor. Still, for the past few years our patient has been able to enjoy more and longer outdoor stays and activities with a clear improvement in quality of life.

Discussion

Albeit this is a rare photodermatosis, we would like to stress the importance of identifying patients suffering from HV, since a pathogenetic relationship between HV and EBV infection has been documented previously and specific therapy therefore is possible. One might be hesitant to believe that oral treatment with acyclovir/valacyclovir could have a positive effect on the symptoms of HV based on the poor experiences in treating infectious mononucleosis with these drugs. However, several case reports, including this one, point to the fact that oral antiviral treatment has a beneficial effect.6 Lastly, it is also important to identify this group of patients due to the risk of complications for example, the possible progression into malignant lymphoma.6 8 9 Our patient fulfilled the criteria for classic HV (photo-induced dermatosis without systemic symptoms), which indicate a good prognosis compared with cases of severe HV (non-photo induction and systemic symptoms), who carry a significant risk of developing lymphoma. However, cases with progression from classic HV to severe HV have been described.8 The significance of clonality, as demonstrated in the skin biopsy of our patient based on TCR monoclonal rearrangement, as risk factor for developing malignant lymphoma is at the moment unresolved. However, patients with classic HV have been reclassified as HV-like lymphoma after demonstration of monoclonal TCR rearrangement.10 On the other hand, a recent study demonstrated monoclonal rearrangement of TCR genes in 13 of 14 patients with HV irrespective of the severity of the skin eruption or the presence or absence of systemic symptoms.11 In this context it would seem reasonable, that our patient should be followed and monitored till complete remission.

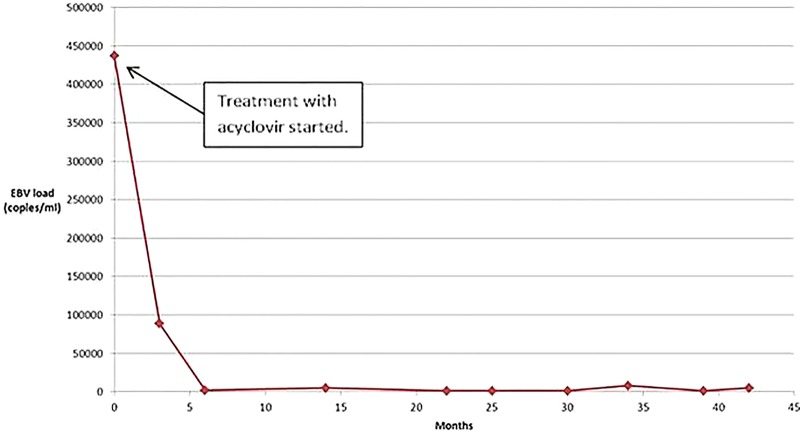

Initially, our patient was treated with fish oil supplements based on past reports.12 13 The effect was at best moderate, but the adherence of our patient to the prescribed treatment was most likely deficient. Following blood analyses and skin biopsy demonstrating EBV, the patient was shifted to specific treatment with acyclovir followed by valacyclovir with good response. One might argue that the improvement in our patient, after the initiation of the antiviral therapy, was due to the natural course of the disease, as HV tends to regress spontaneously. However, the evident overlap between initiation of antiviral therapy, the patient's clinical improvement and the decline in the EBV-DNA load in the patient's blood is striking (figure 4).

Figure 4.

The graph shows a very high initial Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) DNA load in the serum of our patient, which convincingly dropped simultaneously to the initiation of treatment with oral antivirals. The EBV-DNA load has ever since remained at low levels (<8000 copies). Interestingly, the test results have been accompanied by a clear clinical improvement.

In conclusion, we would like to stress the importance of a close collaboration between dermatologists and paediatricians realising that HV is a chronic disease, which is very likely to affect the patients’ quality of life at a very vulnerable age. On that note, one should also bear in mind the risk of progression into lymphoproliferative malignancies. We wish to raise the issue whether quantitative blood EBV-DNA determination in the diagnostic work-up might substitute skin biopsies, which are less favoured and may be rejected by children and their parents. On a final note, we would like to advocate for treatment with acyclovir/valacyclovir, as the number and the risk of side-effects are scarce. Currently, one does not know if antiviral therapy may prevent the development of lymphoproliferative disorders, although the marked reduction in viral load and disease activity could indicate that this may be the case.

Learning points.

Hydroa vacciniforme is an extremely rare photosensitivity disorder of the skin, which primarily affects children.

Recently, a definite association to Epstein-Barr virus infection has been demonstrated.

It is possible that the condition may improve if antiviral treatment with acyclovir or valacyclovir is initiated.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Gupta G, Man I, Kemmett D. Hydroa vacciniforme: a clinical and follow-up study of 17 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000;42(2 Pt 1):208–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta G, Mohamed M, Kemmett D. Familial hydroa vacciniforme. Br J Dermatol 1999;140:124–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Annamalai R. Hydroa vacciniforme in three alternate siblings. Arch Dermatol 1971;103:224–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iwatsuki K, Xu Z, Takata M et al. The association of latent Epstein-Barr virus infection with hydroa vacciniforme. Br J Dermatol 1999;140:715–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirai Y, Yamamoto T, Kimura H et al. Hydroa vacciniforme is associated with increased numbers of Epstein-Barr virus-infected γδT cells. J Invest Dermatol 2012;132:1401–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lysell J, Wiegleb Edstrom D, Linde A et al. Antiviral therapy in children with hydroa vacciniforme. Acta Derm Venereol 2009;89:393–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verneuil L, Gouarin S, Comoz F et al. Epstein-Barr virus involvement in the pathogenesis of hydroa vacciniforme: an assessment of seven adult patients with long-term follow-up. Br J Dermatol 2010;163:174–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iwatsuki K, Satoh M, Yamamoto T et al. Pathogenic link between hydroa vacciniforme and Epstein-Barr virus-associated hematologic disorders. Arch Dermatol 2006;142:587–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iwatsuki K, Ohtsuka M, Akiba H et al. Atypical hydroa vacciniforme in childhood: from a smoldering stage to Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphoid malignancy. J Am Acad Dermatol 1999;40(2 Pt 1):283–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kimura H, Ito Y, Kawabe S et al. EBV-associated T/NK–cell lymphoproliferative diseases in nonimmunocompromised hosts: prospective analysis of 108 cases. Blood 2012;119:673–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quintanilla-Martinez L, Ridaura C, Nagl F et al. Hydroa vacciniforme-like lymphoma: a chronic EBV1 lymphoproliferative disorder with risk to develop a systemic lymphoma. Blood 2013;122:3101–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Durbec F, Reguiai Z, Leonard F et al. Efficacy of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids for the treatment of refractory hydroa vacciniforme. Pediatr Dermatol 2012;29:118–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rhodes LE, White SI. Dietary fish oil as a photoprotective agent in hydroa vacciniforme. Br J Dermatol 1998;138:173–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]