Abstract

Introduction

Postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) is one of the most common complications following herpes zoster. Clinical trials indicate that acupuncture could reduce pain and discomfort among patients with PHN. This protocol aims to describe how to accumulate the current evidence on the efficacy and safety of acupuncture for treating PHN.

Methods and analysis

This systematic review will electronically search multiple databases including the Cochrane Skin Group Trials Register, MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), the Chinese Biomedical Literature Database (CBM), the Chinese Medical Current Content (CMCC) and the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), and will hand search a list of medical journals as a supplement. Any clinical randomised controlled trials related to acupuncture for treating PHN will be included. Outcomes will include pain intensity, global impression, quality of life, safety and costs. By screening the titles, abstracts and full texts, two reviewers will independently select studies, extract data, and assess study quality. Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials will be conducted using Revman 5.1 software. The results will be presented as risk ratio for dichotomous data, and standardised or weighted mean difference for continuous data.

Ethics and dissemination

This systematic review does not need ethical approval because there are no data used in our study that are linked to individual patient data. Also, the findings will be disseminated through a peer-review publication or conference presentation.

Trial registration number

PROSPERO registration number: CRD42014009555.

Keywords: DERMATOLOGY, COMPLEMENTARY MEDICINE, PAIN MANAGEMENT

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This systematic review will assess the efficacy and safety of acupuncture for postherpetic neuralgia (PHN). It will provide a high-quality synthesis of current evidence for policymakers, patients and clinicians seeking innovative and effective ways to treat PHN.

The ability to generate conclusions of high confidence in this study may be limited, due to the heterogeneity in the forms of acupuncture therapies and the qualities of methodology, and the impossibility of searching in all the electronic databases or other data sources.

Introduction

Postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) is a syndrome characterised by pain persisting for more than 3 months following the resolution of herpes zoster.1–4 In addition, the clinical manifestations include allodynia, dysaesthesia and pruritus along the distribution of the involved dermatome. The incidence of PHN is 4/1000 per year, which further increases to 12/1000 among people aged over 80 years.5 The relevant risk factors for PHN include old age, female gender, greater severity of acute pain, greater rash severity, degree of sensory impairment, psychological distress, a painful prodrome, diabetes mellitus, nutritional deficiencies and diminished cell-mediated immunity.6–10 However, the most relevant risk factor is old age.11 12 It is uncommon in people aged under 50 years, but approximately 83% of PHN occurs in those aged above 50 years. 13

Owing to the persisting or intermittent spontaneous pain, PHN has a serious impact on the patients’ daily activities (eg, dressing, bathing, sleep), quality of life, general health, psychological health (eg, depression and difficulty with concentration), and social and economic well-being.14 15 Though the pathophysiology of PHN is poorly understood, postmortem studies in patients with PHN have found demyelination and axonal loss in peripheral nerves and sensory roots.16

Since PHN frequently resolves spontaneously over time and the evaluation is unclear regarding the efficacy of treatments,17 18 pain reduction may be incorrectly attributed to current treatments for PHN. There are conventional treatments for PHN, such as tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), antiepileptics, opioids, tramadol, lidocaine and capsaicin, which are probably effective to relieve some of the pain for a period of time. However, approximately 50% of patients may still not obtain satisfactory analgesia despite treatments with these medications.4 Moreover, being the first-line treatment suggested worldwide for PHN, TCAs and antiepileptics (gabapentin and pregabalin) still bring a high incidence of adverse events, including sedation, xerostomia, confusion, dysrhythmia, weight gain, dizziness, somnolence, fatigue and ataxia.18–21

Acupuncture, which has a history of more than 2000 years in the prevention and treatment of diseases, plays an important role in Traditional Chinese Medicine. Different kinds of acupuncture methods such as fire needling, electroacupuncture, surrounding needling, pyonex, pricking blood and cupping are in use for the treatment of PHN in hospitals in China. In the past 5 years, acupuncture for treating PHN has been used in more than 137 studies. The benefit of the treatment group was reported between 84.1% and 97.5%.22–24 The clinical trials indicate that acupuncture could reduce pain and discomfort among most patients and also remove pain and discomfort among some patients.

However, there is a lack of high-quality current evidence for acupuncture in the treatment of PHN. Thus, this systematic review is conducted to assess the efficacy and safety of acupuncture for PHN in pain relieving and pain removing.

Methods and analysis

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Type of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) will be included without restriction of language or publication type. Moreover, the trials using open label, single blind and double blind design will all be included, while crossover designs and quasi-RCTs will be excluded.

Type of participants

Participants who had been diagnosed as PHN defined as pain persisting over 3 months after resolution of the rush will be all focused on. No restrictions on age, gender or race.

Types of interventions

Any form of acupuncture therapy used in an experimental group will be included, involving acupuncture, electroacupuncture, an elongated needle, a three-edged needle, fire needling, auricular acupuncture, pyonex, moxibustion, pricking blood and cupping.

Control interventions with no treatment control, sham acupuncture control (non-point acupuncture, minimal acupuncture), placebo control and drug therapy control will be included.

Studies with the following comparisons will be included:

Acupuncture versus another therapy.

Acupuncture with another therapy versus the same other therapy.

Acupuncture versus no active intervention.

Acupuncture versus sham acupuncture.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Pain intensityStudies which applied scales such as the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), Numerical Rating Scale (NRS), Verbal Rating Scale (VRS), the Faces Pain Scale-Revised (FPS-R), etc that were used to measure the intensity of pain will be included.

Secondary outcomes

Global impression (the proportion of participants whose symptoms improved after treatments);

Quality of life;

Safety as measured by the incidence and severity of adverse effects;

Costs.

Search methods for identification of studies

A search strategy will be designed and conducted according to the guidance of the Cochrane handbook.25

Electronic searches

We will search the following databases:

The Cochrane Skin Group Trials Register (the inception to 2014.1);

MEDLINE (the inception to 2014.1);

EMBASE (the inception to 2014.1);

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; the inception to 2014.1);

Chinese Biomedical Literature Database (CBM; the inception to 2014.1);

Chinese Medical Current Content (CMCC; the inception to 2014.1);

China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI; the inception to 2014.1).

This review will use the following search terms: postherpetic neuralgia, PHN, herpes zoster, shingles and acupuncture, electro-acupuncture, elongated needle, fire needling, auricular acupuncture, pyonex, moxibustion, pricking blood, three-edged needle, cupping. This study will adapt this strategy to search all the above databases.

There will be no restriction on language or publication type. The search strategy for MEDLINE can be found in online supplementary appendix 1.

Searching other resources

A list of medical journals in university libraries will be searched as a supplement, such as Chinese Acupuncture and Moxibustion (1981–2014.1), Journal of Clinical Acupuncture and Moxibustion (1985–2014.1), Shanghai Journal of Acupuncture and Moxibustion (1982–2014.1) and Acupuncture Research (1976–2014.1).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

A procedure for screening will be discussed and developed before the start of selection. Both the electronically searched outputs and the studies obtained from other sources will be cited in a database created by NoteExpress software. Two reviewers (WL and JZ) will independently screen all the titles and abstracts of studies to find out the duplicates, as well as to review the studies and decide whether they will be included according to the predefined inclusion criteria. If there are studies that could not be clearly included based on both titles and abstracts, full copies will be screened. Once any disagreement occurs, it will be resolved through discussion and resolved by reaching a consensus among the two reviewers (WL and JZ), or by consulting a third arbitrator (ZL). In addition, the κ value calculated by (P observed−P chance)/(1−P chance) will be used to calculate the consistency evaluation between reviewers.

Data extraction and management

Data extractors (WL and JZ) will independently extract data from the included trials by using a piloted data extraction form that has been discussed and developed by all the reviewers. The extracted data will include data for trials, participants, interventions, outcomes and miscellaneous items such as funding sources and ethical approval. Any disagreement in data extraction will be resolved by discussion or consultation with a third arbitrator(ZL). If data presented in studies are unclear, missing or presented in a form that is either unextractable or difficult to reliably extract, the authors of the study will be contacted for clarification.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

According to the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions,25 the reviewers will first access six domains of each trial (sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and ‘other issues’), then summarise the assessments, and finally categorise the included trials into three levels of bias: low, unclear and high risk of bias. The risk of bias will be assessed independently. Any disagreements will be resolved by discussion or consultation with a third arbitrator.

Measures of treatment effect

Where continuous scales of measurement are used to assess the effects of treatment, the weighted mean difference (WMD) with 95% CIs will be used, or the standardised mean difference (SMD) with 95% CI if different measurement tools and units have been used. For dichotomous outcomes, results will be expressed as the relative risk (RR) with 95% CI.

Unit of analysis issues

Studies with multiple intervention groups will be included. Each intervention group will be compared with the single control group.

Dealing with missing data

The authors of the included studies will be contacted to get further information if there are any missing or insufficient data from the trials. Any relevant data obtained in this manner will be included in the review. The intent-to-treat (ITT) principle consisting of available case analysis and full ITT analysis will be applied for statistical analysis, omitting missing data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity will be investigated by the I2 statistic (I2 to or more than 50% was considered indicative of heterogeneity) and the χ2 test.25 An α of 0.1 will be used to determine statistical significance in the χ2 test, and a p value <0.1 will indicate a problem with heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

Funnel plots will be used to assess reporting biases if 10 or more studies are included in a meta-analysis. Such a funnel plot asymmetry could be caused by publication or related biases, or by systematic differences between small and large studies. If a relationship is identified, the clinical diversity of the studies will be further examined as a possible explanation and described in the text. However, since graphical evaluation can be subjective, Egger’s method will also be used to access the reporting biases.26

Data synthesis

The Revman V.5.1 software will be used to conduct meta-analysis and to calculate the RR with 95% CI for the dichotomous data, the WMD or the SMD with 95% CI for continuous data during synthesis. If the same outcome measurement tool and unit is used, the WMD with 95% CI will be calculated, or SMD with 95% CI instead. If the included studies exist heterogeneity, the p value is less than 0.1, the RR, the WMD or the SMD will be calculated by the random effects model. Otherwise, it will be calculated by a fixed effects model.

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analysis will be performed based on different controls, interventions, durations of treatment and outcome measures. Adverse effects will be tabulated and assessed with descriptive techniques.

Sensitivity analysis

For the sensitivity analysis, the meta-analysis will be repeated, substituting decisions alternatively to test the robustness of the primary decisions of the review process.27 The decision nodes are principally the methodological qualities, the sample size and the option of using missing data (available case analysis and full ITT analysis).

Discussion

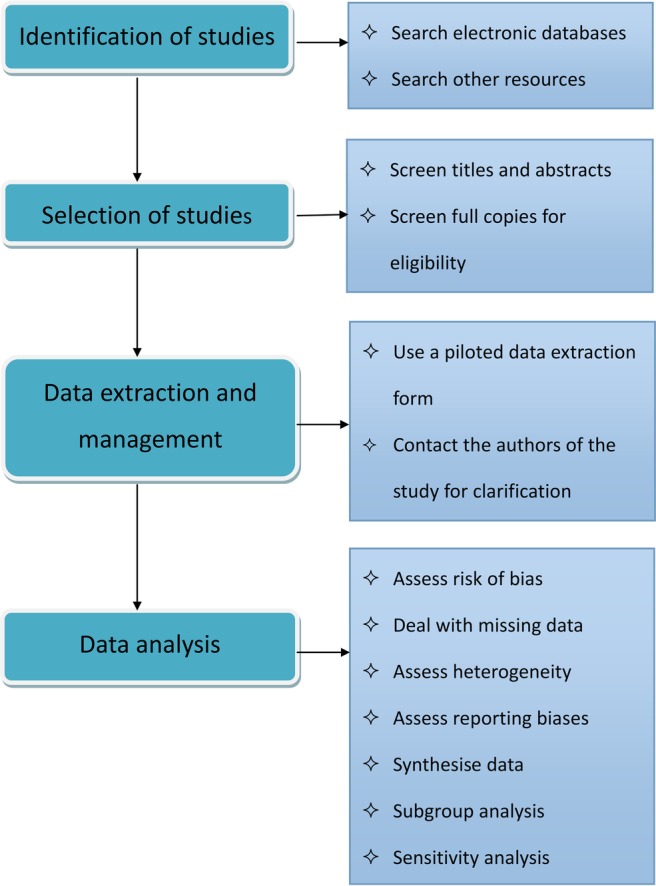

PHN brings a significant adverse impact on patients’ daily activities, quality of life, general health, psychological health, and social and economic well-being. Acupuncture therapy is a suggested intervention in China that may have value to treat PHN, but no high-quality synthesis of the evidence exists. Thus, a high-quality systematic review is needed and the process of performing this study can be found in figure 1, which will be separated into four parts: identification, selection, data extraction and management, and data analysis.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the systematic review.

This study may have limitations that might limit its ability to generate conclusions based on high confidence. Specifically, there may be significant heterogeneity in the forms of acupuncture therapies used and the qualities of methodology. There will also most likely be differences in outcomes measured and tools used. Inherent uncertainty exists by pooling these data within constructed domains.

This review has not searched studies in more electronic databases or a grey list, which could limit the broad search of RCTs to generate the findings.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: WL and ZL contributed to the conception of the study. The manuscript of the protocol was drafted by WL and revised by WP. The search strategy was developed by all authors and run by WL and JZ, who will also independently screen the potential studies, extract data of included studies, assess the risk of bias and finish the data synthesis. ZL will arbitrate the disagreements and ensure that no errors occur during the study. All authors approved publication of the protocol.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The findings of this systematic review will be disseminated via peer-reviewed publications and conference presentations. If the unpublished data from this study are available please contact the corresponding author for further information.

References

- 1.Johnson RW. The future of predictors, prevention, and therapy in postherpetic neuralgia. Neurology 1995;45(12 Suppl 8):S70–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katz J, Cooper EM, Walther RR et al. Acute pain in herpes zoster and its impact on health-related quality of life. Clin Infect Dis 2004;39:342–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hope-Simpson RE. The nature of herpes zoster: a long-term study and a new hypothesis. Proc R Soc Med 1965;58:9–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goßrau G. Postzosterneuralgie. Schmerz 2014;28:93–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merskey HH, Bogduk N. Classification of chronic pain: descriptions of chronic pain syndrome sand definitions of pain terms. 2nd edn Seattle, WA: IASP Press, 1994:212–13. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dongl Z, Li H. Risk factors and preventive measures of postherpetic neuralgia. Chin Rehabil Med 2005;9:118–19. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ducic I, Felder JM III. Peripheral nerve surgery for the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia. Ann Plast Surg 2013;71:384–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen JY, Chang CY, Feng PH et al. Plasma vitamin C is lower in postherpetic neuralgia patients and administration of vitamin C reduces spontaneous pain but not brush-evoked pain. Clin J Pain 2009;25:562–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen JY, Chu CC, Lin YS et al. Nutrient deficiencies as a risk factor in Taiwanese patients with postherpetic neuralgia. Br J Nutr 2011;8:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dworkin RH, Schmader KE. The epidemiology and natural history of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia. In: Watson CPN. ed. Herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia. 2nd edn Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2001:39–65. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donahue JG, Choo PW, Manson JE et al. The incidence of herpes zoster. Arch Intern Med 1995;155:1605–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yawn BP, Saddier P, Wollan PC et al. A population-based study of the incidence and complication rates of herpes zoster before zoster vaccine introduction. Mayo Clin Proc 2007;82:1341–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yawn BP, Saddier P, Wollan PC et al. A population-based study of the incidence and complication rates of herpes zoster before zoster vaccine introduction. Mayo Clin Proc 2007;82:1341–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmader KE. Epidemiology and impact on quality of life of postherpetic neuralgia and painful diabetic neuropathy. Clin J Pain 2002;18:350–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.NICE. NICE clinical guideline 96. Neuropathic pain: the pharmacological management of neuropathic pain in adults in non-specialist settings. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG96 (accessed 5 Jun 2010). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Decroix J, Partsch H, Gonzalez R et al. Factors influencing pain outcome in herpes zoster: an observational study with valaciclovir. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2000;14:23–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Panlilio LM, Christo PJ, Raja SN. Current management of postherpetic neuralgia. Neurologist 2002;8:339–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Christo PJ, Hobelmann G, Maine DN. Post-herpetic neuralgia in older adults. Drugs Aging 2007;24:1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rowbotham M, Harden N, Stacey B et al. Gabapentin for the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1998;280:1837–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rice AS, Maton S.; Postherpetic Neuralgia Study Group . Gabapentin in postherpetic neuralgia: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled study. Pain 2001;94:215–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Marwijk HW, Bijl D, Adegrave HJ et al. Antidepressant prescription for depression in general practicein the Netherlands. Pharm World Sci 2001;23:46–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jing G. Treatment of 40 cases of post-herpetic neuralgia with bloodletting and cupping. Guide China Med 2013;11:292–3. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruiqin Z. Treatment of 40 cases of post-herpetic neuralgia with Bloodletting. Shanxi J TCM 2011;32:595–7. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fang X, Han L, Wu H. Therapeutic effect observation on the treatment of post-herpetic neuralgia with electroacupuncture. People's Mil Med 2013;12:1427–8. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jpt CHH, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1. 0[updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011.

- 26.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deeks J, Higgins J, Altman D. Chapter 9: analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Higgins J, Green S, eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Chichester UK: John Wiley & Sons, 2008:9.37–9.39. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.