Abstract

Objectives

To assess the reproducibility of an educational intervention EdAl-2 (Educació en Alimentació) programme in ‘Terres de l'Ebre’ (Spain), over 22 months, to improve lifestyles, including diet and physical activity (PA).

Design

Reproduction of a cluster randomised controlled trial.

Setting

Two semi-rural town-group primary-school clusters were randomly assigned to the intervention or control group.

Participants

Pupils (n=690) of whom 320 constituted the intervention group (1 cluster) and 370 constituted the control group (1 cluster). Ethnicity was 78% Western European. The mean age (±SD) was 8.04±0.6 years (47.7% females) at baseline. Inclusion criteria for clusters were towns from the southern part of Catalonia having a minimum of 500 children aged 7–8 year; complete data for participants, including name, gender, date and place of birth, and written informed consent from parents or guardians.

Intervention

The intervention focused on eight lifestyle topics covered in 12 activities (1 h/activity/session) implemented by health promoting agents in the primary school over three academic years.

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcome was obesity (OB) prevalence and the secondary outcomes were body mass index (BMI) collected every year and dietary habits and lifestyles collected by questionnaires filled in by parents at baseline and end-of-study.

Results

At 22 months, the OB prevalence and BMI values were similar in intervention and control groups. Relative to children in control schools, the percentage of boys in the intervention group who performed ≥4 after-school PA h/week was 15% higher (p=0.027), whereas the percentage of girls in both groups remained similar. Also, 16.6% more boys in the intervention group watched ≤2 television (TV) h/day (p=0.009), compared to controls; and no changes were observed in girls in both groups.

Conclusions

Our school-based intervention is feasible and reproducible by increasing after-school PA (to ≥4 h/week) in boys. Despite this improvement, there was no change in BMI and prevalence of OB.

Trial registration number:

Clinical Trials NCT01362023.

Keywords: PUBLIC HEALTH, PRIMARY CARE, PREVENTIVE MEDICINE, PAEDIATRICS

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Reproducibility of studies is rare because of the complexity of replicating an intervention programme. Studies in obesity prevention, such as EdAl (Educació en Alimentació), need to be reproducible, especially those improving a healthy lifestyle, including after-school physical activity, to reinforce beneficial practices in childhood.

Statistical methods controlling for confounders and taking into account clustering of data.

Failure to assess treatment adherence to evaluate reproducibility and feasibility.

Dietary habits were noted via a questionnaire that did not take into account the quantities of the different types of food items consumed.

Background

Obesity (OB) has become a disease of epidemic proportions.1 However, this increasing tendency towards excess weight in childhood and adulthood2 observed in some countries (the UK, France, South Korea, the USA and Spain) has stabilised despite the absolute rates being a cause for concern.1 OB prevalence in children and adolescents is higher in southern regions of Europe.3 4

Accumulation of fat tissue constitutes an increased disease risk in childhood, as well as in adulthood.5 This disease risk has a multifactorial aetiology, such as an unhealthy diet and sedentary lifestyle.6 7

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has predicted an increase of 7% in excess weight prevalence in adulthood over the period spanning 2010 to 2020.8 The WHO proposes the prevention and control of OB prevalence as key in the updated ‘Action Plan 2008–2013’ in which effective health promotion is considered as the principal strategy.9

Since excess weight status in adulthood is almost invariably predicated on childhood and adolescent weight, OB prevention should start early in life.10 The optimum age to start an intervention is between the ages of 7 and 8 years because children are more receptive to guidance.11 The school is an ideal place for the promotion of healthy nutrition and lifestyle habits12 and, as some studies have shown, such interventions have inspired changes in nutritional habits and body mass index (BMI) status13 14; the message is received by all schoolchildren, irrespective of ethnic and socioeconomic differences.9 The effectiveness of an intervention is when educational strategies and environmental factors such as healthy nutrition and physical activity (PA) habits coincide since both aspects are essential in preventing childhood OB.15 Currently, European children spend more of their leisure time in sedentary activities such as watching television (TV), video games or on the internet. These activities represent a decrease in physical movement and lowering of energy expenditure and, as such, are risk factors for OB.16

We had designed the EdAl (Educació en Alimentació) programme as a randomised, controlled, parallel study applied in primary schools, and implemented by university students acting as Health Promoter Agents (HPAs).17 This intervention was deployed in Reus (as an intervention group) with the neighbouring towns of Salou, Cambrils and Vilaseca as a control group. The interventions focused on eight lifestyle topics covered in 12 activities (1 h/activity/session) in 7–8-year-old children, and implemented by HPAs over three school academic years. We found that the EdAl programme successfully reduced childhood OB prevalence in boys by 4.39% and increased the percentage of boys who practise ≥5 after-school PA h/week.18 The EdAl programme needed to be reproduced in other localities, and with other children, to demonstrate the effectiveness of this intervention.19

The outcomes of the EdAl programme supported the feasibility of improving PA in childhood. However, an educational intervention, such as our EdAl programme implemented by HPAs, also tests complex components such as healthy lifestyles including diet and PA recommendations. Owing to the complexity, such interventions are difficult to rationalise, standardise, reproduce and administer consistently to all participants.19

There has been one study in the literature that has reproduced its programmes in other locations. Described as the Kiel Obesity Prevention Study (KOPS), the results demonstrated the efficacy and feasibility of implementing new nutritional concepts.20 We tested the reproducibility of the EdAl programme in a geographical area (Terres de l'Ebre) about 80 km away from where the original EdAl programme was designed and implemented. We designed a cluster (town group) randomised controlled trial, the rationale being that since good communications exist between the schools of the same town, this could contribute to schools of the intervention group ‘contaminating’ those of the putative control group.

We describe the primary-school-based study to reduce the prevalence of childhood OB (The EdAl-2 study); the objective remains an intervention to induce healthy lifestyles, including diet and PA recommendations. The study was conducted in 7–8-year-old schoolchildren over three academic years (22 months active school time).

Methods

The original protocol, rationale, randomisation, techniques and results of the initial EdAl programme have been published in Trials.17 18 The current study (EdAl-2) was conducted in exactly the same way so as to assess whether comparable results could be achieved in a different location. The exact intervention is described in more detail in online supplementary file 1, and in this manuscript link. The EdAl-2 study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethical Committee of the Hospital Sant Joan of Reus, Universitat Rovira i Virgili (Catalan ethical committee registry ref 11-04-28/4proj8). This study was registered in Clinical Trials NCT01362023. The protocol conformed to the Helsinki Declaration and Good Clinical Practice guides of the International Conference of Harmonization (ICHGCP). The study followed the CONSORT criteria (see online supplementary additional file 2).

For logistics reasons, the EdAl-2 programme was reduced by 6 months, from 28 to 22 months.

Study population

To approximately ensure a minimum 500 inhabitants of 7–8 years of age per cluster, before randomising the towns (clusters), a statistician who was not familiar with the study objectives and the school identities matched the towns on population size. The coordinating centre (in Reus) developed a cluster randomisation scheme to have a study sample in which the schools in Amposta were designated as cluster A (intervention) and 9 towns around Amposta (Sant Jaume d'Enveja, Els Muntells, l'Ametlla de Mar, El Perelló, l'Ampolla, Deltebre, l'Aldea, Lligalló del Gànguil and Camarles) as cluster B (control). The eligibility criteria of clusters were to be semirural towns from the southern part of Catalonia with a minimum of 500 children of 7–8 years of age in each cluster.

The sociodemographic indicators in all towns were similar to that of the original EdAl programme in Reus. Children attending the schools in both groups (intervention and control) lived in proximity within each school's catchment area. Intervention institutions included five schools involving 18 classrooms and 457 pupils in Amposta. Control institutions consisted of 11 schools involving 23 classrooms and 531 pupils in the nine towns around Amposta. The children in this study are in the second and third grades of primary education (7–8-year-olds). Schoolchildren were enrolled in May 2011 (children born in 2002–2003) and followed up for three school academic years (2012–2013). The study was completed in March 2013.

To be representative of the child population, the schools selected needed to have at least 50% of the children in the classrooms volunteer to participate. We offered the programme to all schools, whether public (funded by the government and termed ‘charter’ schools) or private, which included fee-paying and/or faith schools. Inclusion criteria were: name, gender, date and place of birth, and written informed consent from the parent or guardian of each participant. A questionnaire on eating habits (Krece Plus) developed by Serra Majem et al,21 and PA, level of parental education and lifestyles developed by Llargues et al22 were filled in by the parents at baseline and at the end of the study.

Intervention program

The original EdAl Reus protocol was followed.17 18 The educational intervention activities focused on eight lifestyle topics based on scientific evidence23 to improve nutritional food item choices (and avoidance of some foods) and healthy habits such as teeth-brushing and hand-washing and overall adoption of activities that encourage PA (walking to school, playground games), and to avoid sedentary behaviour.23

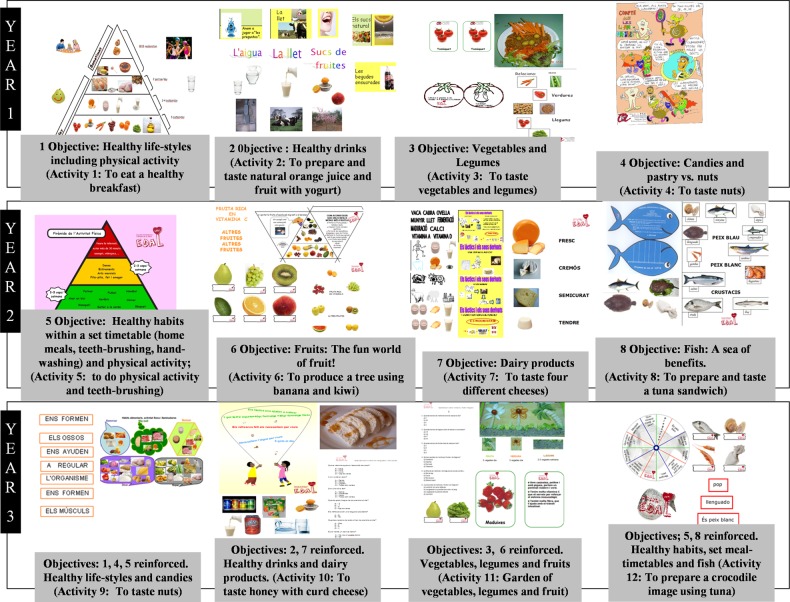

Each of the eight topics described in figure 1 was integrated within educational intervention activities of 1 h/activity, prepared and standardised by the HPAs, and implemented in the children's classrooms. In the first school academic year, we focused on four topics: (1) to improve a healthy lifestyle; (2) to encourage healthy drinks intake (and avoidance of unhealthy carbonated/sweetened beverages); (3) to increase the consumption of vegetables and legumes and (4) to decrease the consumption of candies and pastries while increasing the intake of fresh fruits and nuts. These corresponded to four standardised activities (1 h/activity). In the second year, the remaining four of the eight selected lifestyle topics were addressed: (5) to improve healthy habits within a set timetable (home meals, teeth-brushing, hand-washing) and PA participation; (6) to increase fruit intake; (7) to improve dairy product consumption and (8) to increase fish consumption. These corresponded to four standardised activities. Finally, in the third school academic year, four standardised activities were introduced that reinforced the eight lifestyle topics implemented in the previous two academic years. Thus, the intervention programme was based on eight lifestyle topics incorporated within 12 activities which were disseminated over 12 sessions (1 h/activity/session), and prepared, standardised and implemented as four activities per school academic year by the HPAs in the school classrooms.

Figure 1.

Eight topics of educational intervention activities. This figure shows the eight topics of 12 educational intervention activities of the EdAl programme.

Process evaluation

The measurements were performed in each school academic year, as was the original EdAl programme.17 18

Outcomes

Assessment of the reproducibility of the EdAl programme was based on primary outcomes such as the prevalence of OB (overall as well as stratified by gender), according to the International Obesity Task Force (IOTF)24 recommendations for better international comparisons of data. Secondary outcomes included: changes in measures of adiposity (overall as well as stratified by gender) such as the BMI z-score (based on the WHO growth charts25 and waist circumference, incidence and remission of excess weight (overweight (OW) and OB), as well as changes in lifestyles (eating habits and PA h/week). All outcomes were analysed in the intervention and control groups. Weight, height and waist circumference values were obtained as described previously.17 Prevalence of underweight was analysed according to Cole et al26 using 17 kg/m2 as a cut-off point. The BMI z-score was calculated using the population values of the WHO Global InfoBase.25 To identify the risk factors of OB, the OB category was determined according to the WHO criteria since this is based on data from countries that have a low OB prevalence25 and, as such, provide an understanding of the protective (or risk factors) for OB in our own population. To obtain a measurement of overall improvement in lifestyle, we generated variables such as the maintenance of status in each category as well as the status in relation to changes in each category over the 22-month period.

Sample size

We calculated that to have an 85% chance (at a two-tailed 5% significance level) of detecting a difference of five percentage points between the intervention and control groups (3–8%) with respect to OB prevalence at baseline of the EdAl study,18 354 participants would be required in each of the participation groups. Allowing for an attrition rate of up to 10%, we aimed for 393 participants in each group.

Statistical analyses

Analyses were conducted on student-level data. Descriptive variables were presented as means and CIs (95% CI). General linear mixed models (GLM) were used to analyse differences between the intervention and control pupils with respect to prevalence of OB. Repeated measures of GLM were used to analyse the trend of the BMI z-score between baseline and end-of-study values. The McNemar test was used to analyse change-over-time of food habits, after-school PA h/week and hours TV/day categories, in the intervention and control groups. The continuous variables studied in each group were compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA).

To evaluate the risk and protective factors involved in childhood OB, logistic regression analyses were performed at baseline, with no distinction between the intervention and control groups. The OR and 95% CI were calculated for dietary patterns and lifestyles, based on the Krece Plus Questionnaire21 and the AVall Questionnaire,22 respectively.

The main analyses were performed with the modified intention-to-treat (mITT) population, that is, participants with baseline and end-of-study data on weight, height and date of birth, and written informed consent. The analyses did not use any imputation missing method, the assumption being that missing data were random. Statistical significance was defined by a p<0.05. The statistical analyses were performed with SPSS V.20.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

Enrolment

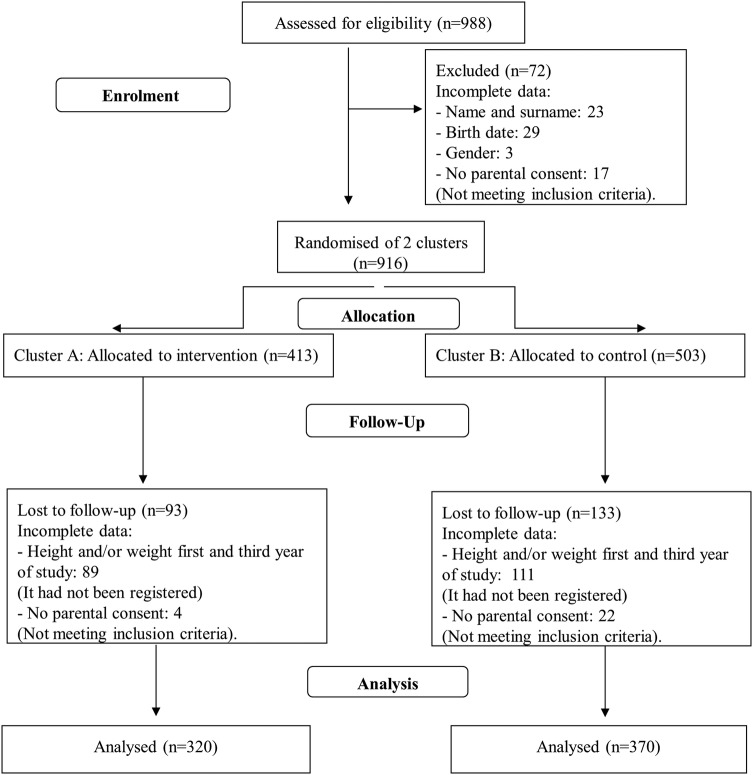

Figure 2 shows the recruitment and flow diagram of pupils in the intervention and control groups over the course of the study. The mITT population in the intervention and control groups was 320 and 370 pupils, respectively. At 22 months, the mean age was 9.67 (95% CI 9.60 to 9.73) in the intervention group (9.68 years in boys and 9.65 years in girls) and 9.86 (95% CI 9.79 to 9.91) in the control group (9.85 years in boys and 9.84 years in girls). The differences in age were not significant in relation to gender.

Figure 2.

Flow of participants through the study. Incomplete height and/or weight (measures of the first and/or third academic year); No parental consent signed (first, second or third academic year).

The characteristics of the study group are summarised in table 1. At baseline, the intervention and control groups were homogeneous in BMI status. The ethnicity of the population was predominantly Western European in the intervention and control groups (77.5% vs 78.9%, respectively) while 7.5% vs 10.8% was Eastern European; 10.3% vs 3.5% was Latin American; 3.4% vs 6.2% was North African Arab. At baseline, there was a significant difference in the distribution with respect to Latin American children (10.3% in the intervention group and 3.5% in the control group; p<0.001). The distribution was random. Of note, there were no significant differences in distributions of OB and/or OW. Also, no differences were observed in terms of response to the intervention in relation to ethnicity.

Table 1.

Anthropometric characteristics of pupils at baseline: intervention versus control group

| Intervention group |

Control group |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (95% CI) |

Mean (95% CI) |

Intervention vs control; p value* | Intervention vs control; p value* | Intervention vs control; p value* | |||||

| Boys (n=165) | Girls (n=155) | Total (n=320) | Boys (n=196) | Girls (n=174) | Total (n=370) | Boys | Girls | Total | |

| Age, years | 8.01 (7.91 to 8.12) | 7.97 (7.88 to 8.07) | 7.99 (7.92 to 8.06) | 8.11 (8.03 to 8.19) | 8.06 (7.97 to 8.15) | 8.09 (8.03 to 8.15) | 0.105 | 0.153 | 0.967 |

| Weight, kg | 30.35 (29.22 to 31.48) | 29.86 (28.81 to 30.91) | 30.11 (29.34 to 30.88) | 31.29 (30.26 to 32.33) | 31.35 (30.36 to 32.34) | 31.32 (30.60 to 32.04) | 0.226 | 0.043 | 0.024 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 17.40 (16.93 to 17.86) | 17.42 (16.97 to 17.88) | 17.41 (17.09 to 17.73) | 17.70 (17.28 to 18.13) | 17.94 (17.51 to 18.37) | 17.82 (17.51 to 18.12) | 0.340 | 0.104 | 0.073 |

| Height, m | 1.32 (1.30 to 1.33) | 1.30 (1.29 to 1.31) | 1.31 (1.30 to 1.32) | 1.32 (1.31 to 1.33) | 1.32 (1.31 to 1.33) | 1.32 (1.31 to 1.33) | 0.242 | 0.045 | 0.027 |

| Fat mass, kg | 6.71 (5.99 to 7.42) | 7.11 (6.50 to 7.72) | 6.90 (6.42 to 7.38) | 6.44 (5.78 to 7.09) | 7.70 (7.12 to 8.27) | 7.03 (6.59 to 7.47) | 0.584 | 0.167 | 0.698 |

| Lean mass, kg | 23.99 (23.34 to 24.64) | 22.86 (22.32 to 23.39) | 23.44 (23.02 to 23.87) | 24.88 (24.28 to 25.47) | 23.71 (23.21 to 24.22) | 24.33 (23.93 to 24.73) | 0.049 | 0.022 | 0.003 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 60.97 (59.68 to 62.27) | 59.91 (58.67 to 61.15) | 60.46 (59.56 to 61.36) | 64.37 (63.18 to 65.56) | 65.17 (64.00 to 66.34) | 64.75 (63.91 to 65.58) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

The results are expressed as mean (95% CI).

*p Value: GLM statistic.

BMI, body mass index; GLM, general linear model.

Attrition rate

Figure 2 shows the recruitment and retention of pupils in intervention and control schools. Among the 916 pupils assessed at the beginning of the study, 690 (75.3%) pupils (73.6% of those allocated to the control group and 77.5% of those allocated to the intervention group) were reassessed three academic courses later, and valid measurements were obtained. The rate of parental consent was 95.7%. Dropouts in both groups are assumed to be missing at random.

Primary outcome: prevalence of OB

At 22 months of the study, OB prevalence assessed by IOTF criteria was similar in the intervention and control groups (p=0.628; table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline and end-of-intervention measurements of categorised BMI in the intervention and control groups

| Criteria/category | Group | Baseline, % (n) | End of study, % (n) | Change, % | Baseline to study end p Value* |

Intervention vs control p Value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IOTF criteria | ||||||

| OW | Intervention | |||||

| Boys | 18.2 (30) | 24.2 (40) | 6 | 0.087 | 0.629 | |

| Girls | 16.2 (25) | 23.2 (36) | 7 | 0.043 | 0.066 | |

| Total | 17.2 (55) | 23.8 (76) | 6.6 | 0.005 | 0.086 | |

| Control | ||||||

| Boys | 25.5 (50) | 27.0 (53) | 1.5 | 0.690 | ||

| Girls | 28.2 (49) | 32.8 (57) | 4.6 | 0.185 | ||

| Total | 26.8 (99) | 29.7 (110) | 2.9 | 0.169 | ||

| OB | Intervention | |||||

| Boys | 9.7 (16) | 11.5 (19) | −1.8 | 0.453 | 0.735 | |

| Girls | 13.6 (21) | 12.3 (19) | −1.3 | 0.754 | 0.732 | |

| Total | 11.6 (37) | 11.9 (38) | 0.3 | 1.000 | 0.628 | |

| Control | ||||||

| Boys | 10.7 (21) | 10.2 (20) | −0.5 | 1.000 | ||

| Girls | 12.1 (21) | 10.9 (19) | −1.2 | 0.687 | ||

| Total | 11.4 (42) | 10.5 (39) | −0.93 | 0.607 |

The results are expressed as % (n).

*p Value: McNemar’s test.

†p Value: Fisher’s exact test.

BMI, body mass index; OB, obesity; OW, overweight; IOTF, International Obesity Task Force.

Secondary outcomes

At 22 months of the study, the status of OW prevalence (according to IOTF criteria) was similar between groups (p=0.086).

There were no significant differences in the BMI z-score between the intervention and control groups (p=0.400; table 3). Despite no differences in the BMI z-score, the boys in the intervention group did not have an increase in percentage fat mass (19.96–20.02%: p=0.896), whereas girls in the intervention group (22.06–23.55%; p<0.001), together with boys (19.18–20.64%, p<0.001) and girls (23.26–24.98%) in the control group, had a significant increase.

Table 3.

BMI z-score at baseline and at the end of intervention in the intervention and control groups

| Baseline Mean (95% CI) |

End of study Mean (95% CI) |

Change Mean (95% CI) |

Baseline to study end p Value* |

Intervention vs control p Value† |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI z-score | |||||

| Intervention | |||||

| Boys | 0.73 (0.53 to 0.94) | 0.74 (0.54 to 0.93) | 0.00 (−0.07 to 0.08) | 0.973 | 0.381 |

| Girls | 0.71 (0.50 to 0.91) | 0.89 (0.68 to 1.10) | 0.18 (0.10 to 0.26) | <0.001 | 0.030 |

| Total | 0.72 (0.58 to 0.86) | 0.81 (0.67 to 0.95) | 0.09 (0.03 to 0.14) | 0.002 | 0.400 |

| Control | |||||

| Boys | 0.83 (0.64 to 1.01) | 0.81 (0.63 to 1.00) | −0.12 (−0.08 to 0.06) | 0.726 | |

| Girls | 0.52 (0.33 to 0.71) | 0.63 (0.44 to 0.83) | 0.11 (0.02 to 0.20) | 0.013 | |

| Total | 0.68 (0.55 to 0.82) | 0.73 (0.60 to 0.86) | 0.05 (−0.01 to 0.10) | 0.100 | |

Differences between intervention and control preintervention versus postintervention.

*p Value: mixed models repeated measures.

†p Value: analysis of variance (ANOVA) model.

BMI, body mass index.

The remission and incidence of OB were similar in the intervention and control groups, as well as when stratified with respect to gender.

Lifestyle evaluation

After 22 months of the study, there were 19.7%, 11.2% and 8.2% more girls in the intervention group who consumed a second fruit per day, one vegetable per day and fast-food weekly than girls in the control group (p<0.001, p=0.017 and p=0.013, respectively). However, there were 17.9% and 17.8% more boys in the intervention group who consumed pastry at breakfast and more than one vegetable a day, compared to boys in the control group (p=0.002 and p=0.001, respectively). Conversely, there were 12.9% and 12.2% more girls in the control group who consumed legumes and cereal breakfast than girls in the intervention group (p=0.013 and p=0.032, respectively; table 4).

Table 4.

Food habits assessed at baseline and at the end of study in the intervention and control groups

| Intervention group |

Control group |

Intervention vs control p Value‡ |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline, % (n) | End of study, % (n) | p Value* | Baseline, % (n) | End of study, % (n) | p Value† | ||

| Krece Plus Questionnaire | |||||||

| Breakfast | |||||||

| Boys | 98.4 (125) | 98.3 (119) | 1 | 97.5 (154) | 92.2 (153) | 0.092 | 0.635 |

| Girls | 98.4 (123) | 99.2 (120) | 1 | 98.7 (148) | 93.8 (135) | 0.016 | 0.453 |

| Total | 98.4 (248) | 98.8 (239) | 1 | 98.1 (302) | 92.9 (288) | 0.003 | 1 |

| Dairy product at breakfast | |||||||

| Boys | 94.5 (121) | 93.5 (116) | 1 | 93.6 (147) | 92.3 (155) | 1 | 1 |

| Girls | 94.3 (116) | 93.4 (113) | 0.508 | 94.0 (141) | 89.7 (131) | 0.039 | 0.325 |

| Total | 94.4 (237) | 93.5 (229) | 0.481 | 93.8 (288) | 91.1 (286) | 0.167 | 0.574 |

| Cereals at breakfast | |||||||

| Boys | 65.6 (82) | 66.4 (81) | 0.864 | 59.1 (88) | 54.6 (89) | 0.743 | 0.706 |

| Girls | 61.5 (75) | 49.6 (58) | 0.036 | 59.7 (86) | 60.0 (87) | 0.880 | 0.031 |

| Total | 63.6 (157) | 58.2 (139) | 0.098 | 59.4 (174) | 57.1 (176) | 1 | 0.225 |

| Pastry at breakfast | |||||||

| Boys | 15.8 (19) | 23.5 (28) | 0.027 | 22.5 (33) | 12.3 (20) | 0.001 | 0.002 |

| Girls | 20.5 (24) | 15.5 (18) | 0.383 | 15.9 (22) | 12.4 (18) | 0.210 | 0.260 |

| Total | 18.1 (43) | 19.6 (46) | 0.441 | 19.1 (55) | 12.3 (38) | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| Daily fruit or natural juice | |||||||

| Boys | 73.4 (94) | 76.2 (93) | 0.523 | 74.8 (116) | 76.0 (127) | 1 | 0.535 |

| Girls | 66.7 (82) | 70.0 (84) | 0.690 | 79.9 (119) | 73.5 (108) | 0.243 | 0.549 |

| Total | 70.1 (176) | 13.1 (177) | 0.382 | 77.3 (235) | 74.8 (235) | 0.443 | 0.472 |

| Fruit, 2nd per day | |||||||

| Boys | 39.7 (50) | 41.2 (49) | 0.581 | 44.5 (69) | 34.1 (56) | 0.006 | 0.141 |

| Girls | 26.4 (32) | 47.5 (56) | 0.000 | 44.8 (64) | 39.0 (57) | 0.281 | <0.001 |

| Total | 33.2 (82) | 44.3 (105) | 0.001 | 44.6 (133) | 36.5 (113) | 0.004 | <0.001 |

| Dairy product, 2nd per day | |||||||

| Boys | 87.2 (109) | 78.5 (95) | 0.029 | 80.0 (124) | 69.5 (116) | 0.174 | 0.194 |

| Girls | 80.5 (99) | 79.8 (95) | 1 | 71.6 (106) | 75.5 (111) | 0.749 | 0.460 |

| Total | 83.9 (208) | 79.2 (190) | 0.161 | 75.9 (230) | 72.3 (227) | 0.51 | 0.384 |

| Vegetables, daily | |||||||

| Boys | 65.6 (84) | 74.4 (90) | 0.043 | 71.1 (113) | 70.8 (119) | 1 | 0.473 |

| Girls | 71.7 (86) | 77.5 (93) | 0.169 | 68.7 (101) | 63.3 (93) | 0.152 | 0.017 |

| Total | 68.5 (170) | 75.9 (183) | 0.011 | 69.9 (214) | 67.3 (212) | 0.374 | 0.028 |

| Vegetables, >1 per day | |||||||

| Boys | 19.3 (23) | 29.1 (34) | 0.017 | 28.7 (43) | 20.7 (34) | 0.009 | 0.001 |

| Girls | 25.4 (31) | 34.5 (40) | 0.052 | 30.3 (43) | 23.1 (33) | 0.110 | 0.149 |

| Total | 22.4 (54) | 31.8 (74) | 0.001 | 29.5 (86) | 21.8 (67) | 0.002 | 0.001 |

| Fish, regularly | |||||||

| Boys | 73.2 (93) | 76.6 (95) | 0.608 | 70.0 (112) | 70.1 (115) | 0.851 | 0.058 |

| Girls | 71.8 (92) | 71.4 (85) | 0.307 | 74.5 (111) | 71.0 (103) | 1 | 0.662 |

| Total | 74 (185) | 74.1 (180) | 0.896 | 72.2 (223) | 70.6 (218) | 0.791 | 0.312 |

| Fast food, >1 per week | |||||||

| Boys | 6.3 (8) | 7.4 (9) | 1 | 7.1 (11) | 4.9 (8) | 0.227 | 0.106 |

| Girls | 3.3 (4) | 10.1 (12) | 0.109 | 4.2 (6) | 2.8 (4) | 0.219 | 0.013 |

| Total | 4.8 (12) | 8.8 (21) | 0.21 | 5.7 (17) | 3.9 (12) | 0.049 | 0.003 |

| Legumes, >1 per week | |||||||

| Boys | 70.3 (90) | 71.1 (86) | 0.648 | 67.5 (106) | 65.9 (110) | 1 | 0.555 |

| Girls | 72.8 (91) | 73.3 (88) | 0.815 | 62.8 (145) | 76.2 (112) | 0.001 | 0.013 |

| Total | 71.5 (181) | 72.2 (174) | 1 | 65.2 (251) | 70.7 (222) | 0.025 | 0.027 |

| Candy, >1 per day | |||||||

| Boys | 14.3 (18) | 12.6 (15) | 1 | 17.2 (27) | 18.2 (30) | 1 | 0.367 |

| Girls | 12.9 (16) | 12.0 (14) | 1 | 18.7 (26) | 11.1 (16) | 0.078 | 1 |

| Total | 13.6 (34) | 12.3 (29) | 1 | 17.9 (53) | 14.9 (46) | 0.262 | 0.479 |

| Pasta or rice daily | |||||||

| Boys | 63.8 (81) | 67.5 (83) | 0.839 | 69.0 (109) | 67.9 (114) | 0.871 | 0.708 |

| Girls | 59.2 (74) | 64.7 (77) | 0.377 | 68.0 (100) | 69.4 (102) | 0.618 | 0.724 |

| Total | 61.5 (155) | 66.1 (160) | 0.35 | 68.5 (209) | 68.6 (216) | 0.561 | 1 |

| Cooking with olive oil at home | |||||||

| Boys | 97.7 (126) | 98.4 (122) | 1 | 98.1 (157) | 98.8 (167) | 1 | 0.636 |

| Girls | 98.4 (125) | 99.2 (120) | 0.623 | 97.3 (145) | 98.0 (145) | 1 | 0.628 |

| Total | 98 (251) | 98.8 (242) | 0.5 | 97.7 (302) | 98.4 (312) | 0.754 | 0.476 |

| AVall questionnaire | |||||||

| Before leaving home | |||||||

| Dairy products | |||||||

| Boys | 90 (117) | 87.3 (110) | 0.065 | 83.6 (133) | 95.3 (139) | 1 | 0.074 |

| Girls | 87.3 (110) | 87.8 (108) | 0.503 | 83 (122) | 76.4 (110) | 0.004 | 0.235 |

| Total | 90.9 (227) | 87.6 (218) | 0.071 | 86.2 (255) | 81.1 (249) | 0.044 | 0.836 |

| Pastry | |||||||

| Boys | 4 (5) | 2.4 (3) | 1 | 0.7 (1) | 1.4 (2) | 1 | 0.610 |

| Girls | 0.8 (1) | 1. 7 (2) | 1 | 0.7 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 2.5 (6) | 2 (5) | 1 | 0.7 (2) | 0.7 (2) | 1 | 0.606 |

| Cereals | |||||||

| Boys | 33.9 (43) | 36.8 (46) | 0.711 | 30.7 (46) | 35.0 (55) | 0.608 | 1 |

| Girls | 32.2 (38) | 26.2 (32) | 0.405 | 25.2 (37) | 26.2 (37) | 0.458 | 0.297 |

| Total | 33.1 (81) | 31.6 (78) | 0.89 | 27.9 (83) | 30.9 (92) | 0.314 | 0.409 |

| Fresh fruit or natural juice | |||||||

| Boys | 18.4 (23) | 24.6 (31) | 0.189 | 17.0 (26) | 21.2 (32) | 1 | 0.537 |

| Girls | 14.2 (17) | 24.6 (30) | 0.064 | 18.5 (27) | 23.6 (33) | 0.541 | 0.332 |

| Total | 16.3 (40) | 24.6 (61) | 0.016 | 17.7 (53) | 22.3 (65) | 0.560 | 0.256 |

| Sandwich | |||||||

| Boys | 6.6 (8) | 17.7 (22) | 0.115 | 17.3 (26) | 21.1 (32) | 0.458 | 1 |

| Girls | 0.3 (12) | 19.7 (24) | 0.049 | 14.9 (21) | 18.4 (26) | 0.572 | 1 |

| Total | 8.4 (20) | 18.7 (46) | 0.008 | 16.2 (47) | 19.8 (58) | 0.289 | 0.889 |

| Juice package/soft drinks | |||||||

| Boys | 6.7 (8) | 7.4 (9) | 0.754 | 8.7 (13) | 7.1 (11) | 1 | 0.756 |

| Girls | 7.7 (9) | 5.0 (6) | 0.508 | 8.6 (12) | 10.8 (15) | 1 | 0.507 |

| Total | 7.2 (17) | 6.2 (15) | 0.359 | 8.6 (25) | 8.9 (26) | 0.845 | 0.483 |

| Break (midmorning) | |||||||

| Dairy products | |||||||

| Boys | 16.0 (20) | 20.0 (24) | 0.824 | 15.3 (22) | 14.4 (21) | 1 | 0.819 |

| Girls | 8.7 (10) | 9.6 (11) | 0.388 | 10.7 (15) | 8.4 (11) | 1 | 0.595 |

| Total | 12.5 (30) | 15 (35) | 0.367 | 13.0 (37) | 11.6 (32) | 1 | 0.488 |

| Pastry | |||||||

| Boys | 4.1 (5) | 0.8 (1) | 0.625 | 4.1 (6) | 2.1 (3) | 1 | 1 |

| Girls | 0.9 (1) | 0.9 (1) | 1 | 1.5 (2) | 2.3 (3) | 1 | 0.480 |

| Total | 2.5 (6) | 0.9 (2) | 0.687 | 2.8 (8) | 2.2 (6) | 0.687 | 1 |

| Cereals | |||||||

| Boys | 3.3 (4) | 5.9 (7) | 0.727 | 5.7 (8) | 4.9 (7) | 1 | 1 |

| Girls | 3.5 (4) | 3.4 (4) | 1 | 4.3 (6) | 6.9 (9) | 0.180 | 0.544 |

| Total | 3.4 (8) | 4.7 (11) | 0.804 | 5 (14) | 5.9 (16) | 0.238 | 0.659 |

| Fresh fruit or natural juice | |||||||

| Boys | 16.3 (20) | 10.1 (12) | 0.804 | 19.5 (30) | 14.5 (22) | 0.189 | 0.787 |

| Girls | 15.5 (18) | 16.8 (20) | 0.424 | 20.1 (29) | 20.3 (28) | 0.815 | 1 |

| Total | 15.9 (38) | 13.4 (32) | 0.856 | 19.8 (59) | 17.2 (50) | 0.522 | 0.721 |

| Sandwich | |||||||

| Boys | 28.3 (36) | 37.7 (46) | 0.087 | 43.2 (67) | 41.6 (67) | 0.701 | 0.080 |

| Girls | 24.8 (30) | 33.6 (41) | 0.064 | 29.7 (44) | 41.1 (58) | 0.016 | 0.860 |

| Total | 26.6 (66) | 35.7 (87) | 0.008 | 36.6 (111) | 41.4 (125) | 0.185 | 0.299 |

| Juice package/soft drinks | |||||||

| Boys | 7.4 (9) | 9.1 (11) | 0.344 | 12.2 (18) | 12.6 (19) | 1 | 1 |

| Girls | 7.8 (9) | 6.1 (7) | 0.727 | 12.1 (17) | 13.2 (18) | 1 | 0.233 |

| Total | 7.6 (18) | 7.7 (18) | 0.815 | 12.2 (35) | 12.9 (37) | 1 | 0.543 |

Bold typeface indicates p<0.05. *p Value: McNemar’s test (changes in the intervention group).

†p Value: McNemar’s test (changes in the control group).

‡p Value: Fisher’s exact test.

Table 5 summarises the time spent in after-school PA, watching TV, playing video games and other leisure-time activities. At 22 months, the percentage of boys in the intervention group who performed ≥4 h after-school PA/week was increased by 15% (p=0.027) while there were 16.6% more boys in the intervention group watching ≤2 h TV/day (p<0.009). The results indicate less sedentary behaviour in intervention than control individuals.

Table 5.

Lifestyles assessed at baseline and at the end of study in intervention and control

| Intervention |

Control |

Intervention vs control p Value‡ |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline, % (n) | End of study, % (n) | p Value* | Baseline, % (n) | End of study, % (n) | p Value† | ||

| TV and/or video games | |||||||

| 0–2 h/day | |||||||

| Boys | 49.2 (62) | 45.2 (57) | 0.268 | 32.5 (51) | 27.0 (43) | 0.627 | 0.71 |

| Girls | 48.4 (60) | 51.2 (63) | 1 | 44.0 (66) | 49.7 (71) | 0.43 | 0.287 |

| Total | 48.8 (122) | 48.2 (120) | 0.464 | 38.1 (117) | 37.7 (114) | 0.91 | 0.697 |

| 3–4 h/day | |||||||

| Boys | 46.0 (58) | 50.0 (63) | 0.542 | 62.4 (98) | 63.5 (101) | 1 | 0.874 |

| Girls | 43.5 (54) | 44.7 (55) | 0.86 | 54.0 (81) | 47.6 (68) | 0.349 | 0.71 |

| Total | 44.8 (112) | 47.4 (118) | 0.489 | 58.3 (179) | 56.0 (169) | 0.606 | 0.632 |

| >4 h/day | |||||||

| Boys | 4.8 (6) | 4.8 (6) | 0.375 | 5.1 (8) | 9.4 (15) | 0.607 | 0.393 |

| Girls | 8.1 (10) | 4.1 (5) | 0.453 | 2.0 (3) | 2.8 (4) | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 6.4 (16) | 4.4 (11) | 1 | 3.6 (11) | 6.3 (19) | 0.481 | 0.462 |

| After-school PA | |||||||

| 0–2 h/week | |||||||

| Boys | 26.2 (34) | 14.5 (18) | 0.013 | 21.5 (34) | 19.0 (31) | 0.286 | 0.354 |

| Girls | 35.2 (43) | 33.6 (41) | 0.701 | 34.5 (50) | 36.6 (52) | 1 | 0.557 |

| Total | 30.6 (77) | 24.0 (59) | 0.049 | 27.7 (84) | 27.2 (83) | 0.435 | 0.254 |

| 2–4 h/week | |||||||

| Boys | 29.2 (38) | 24.2 (30) | 0.418 | 38.0 (60) | 3.1 (54) | 0.78 | 0.602 |

| Girls | 36.9 (45) | 32.0 (39) | 0.377 | 32.4 (47) | 31.0 (44) | 1 | 0.155 |

| Total | 32.9 (83) | 28.0 (69) | 0.188 | 35.3 (107) | 32.1 (98) | 0.764 | 0.135 |

| >4 h/week | |||||||

| Boys | 44.6 (58) | 61.3 (76) | 0.006 | 40.5 (64) | 47.9 (78) | 0.243 | 0.643 |

| Girls | 27.9 (34) | 34.4 (42) | 0.136 | 33.1 (48) | 32.4 (46) | 0.868 | 0.598 |

| Total | 36.5 (92) | 48.0 (118) | 0.002 | 37.0 (112) | 40.7 (124) | 0.272 | 0.485 |

Bold typeface indicates p<0.05. *p Value: McNemar’s test (changes in the intervention group).

†p Value: McNemar’s test (changes in the control group).

‡p Value: Fisher’s exact test.

PA, physical activity; TV, television.

Differences between intervention and control pre–post intervention programme.

At 22 months, participants who were normal weight at baseline increased after-school PA to ≥4 h/week. This reflects a rise to 32.7% in boys (p=0.002). However, in girls, the changes were not statistically different (p=0.134). No statistically significant differences were observed in the control group.

Impact of certain additional factors on OB

The ORs of OB, using BMI z-score criteria, were related to some of the more relevant dietary habits and lifestyles. Thus, breakfast dairy product consumption (OR=0.336; p=0.004) and ≥4 after-school PAh/week (OR=0.600; p=0.032) were protective factors against OB. Conversely, doing <4 h/week PA (OR=1.811; p=0.018) increased the risk of childhood OB.

Discussion

The EdAl-2 programme, a reproducibility study in Terres de l'Ebre, shows that intervention is useful for improving weekly after-school PA. However, the OB prevalence remained unchanged at 22 months, as has been shown in the data on stability of OB prevalence observed in some European countries.8 Despite the maintenance of OW and OB prevalence in both groups, fat mass percentage had increased in girls of the intervention and control group, whereas it remained similar in boys of intervention group.

As proposed by Kain et al, designing a new school-based intervention study needs to have some critical aspects considered. These include the following: the random allocation of schools, although methodologically desirable, is not always possible; participation of parents is very limited; OB is not recognised as a problem; and increasing PA and implementing training programmes for teachers is difficult due to an inflexible curriculum and lack of teachers’ time. Unless these barriers are overcome, OB prevention programmes will not produce positive and lasting outcomes.27 As such, our programme of HPA-implemented intervention activities in classrooms is an attractive alternative that circumvents lack-of-teacher-time.

The EdAl-2 programme confirmed that after-school PA (in terms of h/week) can be stimulated in primary school as part of a healthy lifestyle. As we had observed in the original EdAl programme18 at 28 months of intervention, there was an increase of up to 19.7% of children dedicating >5 h/week to extra-curricular physical activities.18 Further, the after-school PA was maintained despite cessation of the intervention programme.28 The effect of the EdAl programme during its implementation and after the official cessation indicated an impact on PA, whereas modification towards healthy food choices occurred according to the site of the programme's implementation, and was not consistent.

Interventions to prevent OB in the school setting have shown dramatic improvements.29 However, successful studies in OB prevention need to be reproducible, especially those improving healthy lifestyle such as after-school PA, to confirm best childhood practices.

Reproducibility of studies is rare because of the complexity of trying to replicate a programme. To standardise a method, it is essential to be able to reproduce appropriate levels of an intervention, especially one that involves behavioural changes. The feasibility of our intervention was confirmed in two different towns and over two different timecourses (the first in Reus over 28 months, and the second in Amposta over 22 months).

Also, it is important to assess treatment adherence in order to evaluate reproducibility and feasibility.19 For example, the KOPS study20 demonstrated that nutritional knowledge was increased as a result of the intervention in the two cohort studies (KOPS 1 and KOPS 2).20 However, the study was unable to show whether there were differences in OW outcomes, weight categories or lifestyles between the two cohorts. Some multicentred studies have attempted to reproduce methodological aspects in interventions conducted in different countries or different populations. However, while multicentred studies are usually implemented concurrently, reproducibility involves the applicability of the intervention at different sites and/or different times in order to validate the initial findings. One example of this is the Pro Children Study,30 which, as a multicentred study, had been applied in different countries simultaneously and had demonstrated its efficacy and feasibility.

The ALADINO study presented the OB status prevalence in Spain, which, according to the IOTF, is about 11.4% in children around 9 years of age.31 In the EdAl-2 study, the OB prevalence was similar, but lower in the intervention group than the equivalent in the ALADINO study and as well in the EdAl-2 control group.

The EdAl-2 study showed a significant improvement of 16.7% in the young boys in the intervention group who participated in the ≥4 h/week after-school PA. Further, the increased numbers of children in the intervention group who performed ≥4 h/week after-school PA, who were normal weight at baseline, suggested that the intervention was effective not only in the primary-school healthy population but also in preventing OB over the longer term due to the PA being maintained.

In the dietary habits aspect of the EdAl-2 study, we observed that the increase in healthy lifestyle habits, such as the increase in fruit and vegetables consumption and increasing PA h/week while maintaining low TV h/day, is promising lifestyle changes that could induce a reduction of OW and OB over the long term.

In the EdAl-2 study, we observed that consumption of dairy products at breakfast was a protective factor against OB.

Several studies have shown that participating in PA was a protective factor against OB and that spending >2 h watching TV was a risk factor for childhood OB. A recent Spanish study showed that leisure-time PA was a protective factor against OB (as with our present study) and that performing >4 h/week is a protective factor while watching TV for this amount of time was, according to Ochoa et al,32 associated with OB.

There are several limitations to our study. First, we evaluated dietary habits via a questionnaire that did not take into account the quantities of the different types of food items consumed. These data would be important in addressing the quantity versus quality debate in OB or OW prevalence. Second, assigning control groups according to towns surrounding the intervention town could be a limitation. However, schools in the same town have good relationships and communications with each other and this could entail a possible contamination between schools if assigned to intervention or control status within the same town. This cross-contamination would be minimised if the schools themselves were assigned to intervention or control. Third, the significant difference in Latin American ethnicity between the two groups of the study at baseline could be a limitation. However, there were no significant differences in distributions of OB and/or OW. Also, no differences were observed in terms of response to the intervention study in relation to ethnicity. Fourth, when asked about fast-food consumption, the participants interpreted this as pertaining only to fast-food outlets such as burger shops, and did consider other concepts such as frozen pizza consumed at home. Finally, another limitation could be the proportion of females who may have started puberty in the course of the study. This implies changes in body composition. However, both study groups (intervention and control) had a similar proportion of females with a similar age, and this could cancel out the effect.

Further, EdAl-2 demonstrated that performing >4 h/week after-school PA, plus having dairy products at breakfast are protective factors. Hence, we believe that participating in >4 h/week after-school PA and continuing with a healthy breakfast are key points in preventing childhood OB.

Conclusion

Our school-based intervention is feasible and reproducible by increasing after-school PA (to ≥4 h/week) in boys. Despite this improvement, there was no change in BMI and prevalence of OB. This suggests that our intervention programme induces healthy lifestyle effects (such as more exercise and less sedentary behaviour), which can produce anti-OB benefits in children in the near future beyond the limited length of our current study. However, the effects on girls’ behaviour need to be more closely studied, together with a future repeat of our study in a different population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors express their appreciation to the university medical and health science students of the Facultat de Medicina i Ciències de la Salut, Universitat Rovira i Virgili (Reus, Spain) as well as the staff and parents of the pupils of the primary schools of Amposta, Sant Jaume d'Enveja, Els Muntells, l'Ametlla de Mar, El Perelló, l'Ampolla, Deltebre, l'Aldea, Lligalló del Gànguil and Camarles for their enthusiastic support of this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: MG, EL, LT and RS designed the study (project conception, development of the overall research plan and study oversight). MG, EL, LT, RQ and RS conducted research (hands-on conduct of the experiments and data collection). EL, LT, MG and RS provided essential materials (applies to authors who contributed by providing constructs, database, etc. necessary for the research). DM, EL and LT analysed data or performed statistical analysis. RS, MG, LT, DM and EL drafted and revised the manuscript (authors who made a major contribution). The final manuscript was read and approved by all co-authors. RS, MG take primary responsibility for the study and manuscript content.

Funding: This work has been supported by Diputació de Tarragona 2011 which give a grant to Universitat Rovira iVirgili, and Ajuntament d'Amposta which provided the foods to develop the activities in the schools.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The EdAl-2 study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethical Committee of the Hospital Sant Joan of Reus, Universitat Rovira i Virgili (Catalan ethical committee registry ref 11-04-28/4proj8).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Technical appendix, statistical code and data set available at the Dryad repository in: “Data from: EdAl-2 (Educació en Alimentació) programme: reproducibility of a cluster randomised, interventional, primary-school-based study to induce healthier lifestyle activities in children” (10.5061/dryad.t5825;005496).

References

- 1.Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económicos (OCDE): Obesity update 2012.

- 2.World Health Organization. The Challenge of obesity in the WHO European region and the strategies for response Denmark, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahrens W, Bammann K, Siani A, et al. ; IDEFICS Consortium. The IDEFICS cohort: design, characteristics and participation in the baseline survey. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011;35(Suppl 1):S3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brug J, van Stralen MM, Te Velde SJ et al. Differences in weight status and energy-balance related behaviors among schoolchildren across Europe: the ENERGY-project. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e34742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martos-Moreno GA, Argente J. Paediatric obesities: from childhood to adolescence. An Pediatr (Barc) 2011;75:63e1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manco M, Dallapiccola B. Genetics of pediatric obesity. Pediatrics 2012;130:123–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vos MB, Welsh J. Childhood obesity: update on predisposing factors and prevention strategies. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2010;12:280–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD): obesity Update 2012. http://www.oecd.org/health/49716427.pdf

- 9.Van Cauwenberghe E, Maes L, Spittaels H. Effectiveness of school-based interventions in Europe to promote healthy nutrition in children and adolescents: systematic review of published and ‘grey’ literature. Br J Nutr 2010;103:781–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reinehr T, Wabitsch M. Childhood obesity. Curr Opin Lipidol 2011;22:21–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guia de práctica clínica (GPC). AATRM2007.

- 12.Verbestel V, De Henauw S, Maes L et al. Using the intervention mapping protocol to develop a community-based intervention for the prevention of childhood obesity in a multi-centre European project: the IDEFICS intervention. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2011;8:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vio F, Zacarías I, Lera L et al. Prevención de la obesidad en escuelas básicas de Peñalolén: Componente alimentación y nutrición. Rev Chil Nutr 2011;38:268–76. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bacardí-Gascon M, Pérez-Morales ME, Jiménez-Cruz A. A six month randomized school intervention and an 18-month follow-up intervention to prevent childhood obesity in Mexican elementary schools. Nutr Hosp 2012;27:755–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Bourdeaudhuij I, Van Cauwenberghe E, Spittaels H et al. School-based interventions promoting both physical activity and healthy eating in Europe: a systematic review within the HOPE project. Obes Rev 2011;12:205–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Papandreou D, Malindretos P, Rousso I. Risk factors for childhood obesity in a Greek paediatric population. Public Health Nutr 2010;13:1535–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giralt M, Albaladejo R, Tarro L et al. A primary-school-based study to reduce prevalence of childhood obesity in Catalunya (Spain)—EDAL-Educacio en alimentacio: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2011;12:54–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tarro L, Llauradó E, Albaladejo R et al. A primary-school-based study to reduce the prevalence of childhood obesity—the EdAl (Educació en Alimentació) study: a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2014;15:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG et al. Extending the CONSORT statement to randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatment: explanation and elaboration .Ann Intern Med 2008;148:295–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Danielzik S, Pust S, Muller MJ. School-based interventions to prevent overweight and obesity in prepubertal children: process and 4-years outcome evaluation of the Kiel Obesity Prevention Study (KOPS). Acta Paediatr Suppl 2007;96:19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Serra Majem L, Ribas Barba L, Aranceta Bartrina J et al. Childhood and adolescent obesity in Spain. Results of EnKid study (1998–2000). Med Clin (Barc) 2003;12:725–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Llargues E, Franco R, Recasens A et al. Assessment of a school-based intervention in eating habits and physical activity in school children: the AVall study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2011;65:896–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gidding SS, Dennison BA, Birch LL et al. Dietary recommendations for children and adolescents: a guide for practitioners: consensus statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2006;113(Suppl 23):e857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM et al. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ 2000;320:1240–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization. Growth Reference data for 5–19 years 2007. http://www.who.int/growthref/en/ (accessed 05 Mar 2014).

- 26.Cole TJ, Flegal KM, Nicholls D et al. Body mass index cut offs to define thinness in children and adolescents: international survey. BMJ 2007;335:194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kain J, Uauy R, Concha F et al. School-based obesity prevention interventions for Chilean children during the past decades: lessons learned. Adv Nutr 2012;3:616S–21S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tarro L, Llauradó E, Moriña D, et al. Follow-up of a Healthy Lifestyle Education Program (the Educació en Alimentació Study): 2 years after cessation of intervention. J Adolesc Health 2014;S1054-139X (14)00280-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Brown T, Summerbell C. Systematic review of school-based interventions that focus on changing dietary intake and physical activity levels to prevent childhood obesity: an update to the obesity guidance produced by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Obes Rev 2009;10:110–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Te Velde SJ, Brug J, Wind M et al. Effects of a comprehensive fruit- and vegetable-promoting school-based intervention in three European countries: the Pro Children Study. Br J Nutr 2008;99:893–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pérez-Farinós N, López-Sobaler AM, Dal Re MA et al. The ALADINO Study: a national study of prevalence of overweight and obesity in Spanish children in 2011. Biomed Res Int 2013;2013:163687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ochoa MC, Moreno-Aliaga MJ, Martinez-Gonzalez MA et al. Predictor factors for childhood obesity in a Spanish case-control study. Nutrition 2007;23:379–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.