Abstract

Objective

To estimate isotretinoin exposure in Dutch pregnant women despite the implemented pregnancy prevention programme (PPP) and second, to analyse the occurrence of adverse fetal or neonatal outcomes in these isotretinoin exposed pregnancies.

Design

Population-based study.

Setting

The Netherlands.

Participants

A cohort of 203 962 pregnancies with onset between 1 January 1999 and 1 September 2007 consisting of 208 161 fetuses or neonates.

Main outcome measures

Isotretinoin exposure in the 30 days before or during pregnancy. Proportions of adverse fetal or neonatal outcomes, defined as intrauterine deaths ≥16 week of gestation and neonates with major congenital anomalies. ORs with 95% CIs adjusted for maternal age were calculated to estimate the risk of adverse fetal or neonatal outcome after maternal isotretinoin exposure.

Results

51 pregnancies, 2.5 (95% CI 1.9 to 3.3) per 10 000 pregnancies, were exposed to isotretinoin despite the pregnancy prevention programme. Forty-five of these pregnancies, 2.2 (95% CI 1.6 to 2.9) per 10 000 pregnancies, were exposed to isotretinoin during pregnancy and six additional women became pregnant within 30 days after isotretinoin discontinuation. In 60% of isotretinoin exposed pregnancies, women started isotretinoin while already pregnant. In five out of the 51 isotretinoin exposed pregnancies (53 fetuses), 9.4% (95% CI 1.3% to 17.6%), had an adverse fetal or neonatal outcome. The OR for adverse fetal or neonatal outcomes after isotretinoin exposure in 30 days before or during pregnancy was 2.3 (95% CI 0.9 to 5.7) after adjustment for maternal age.

Conclusions

Although a PPP was already implemented in 1988, we showed that isotretinoin exposed pregnancies and adverse fetal and neonatal events potentially related to the exposure still occur. These findings from the Netherlands add to the evidence that there is no full compliance to the isotretinoin PPP in many Western countries. Given the limited success of iPLEDGE, the question is which further measures are able to improve compliance.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY, isotretinoin, pregnancy prevention programme

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first population-based study in the European Union (EU) on isotretinoin exposure during pregnancy in a large cohort of more than 200 000 pregnancies which enabled estimating isotretinoin exposure rates among pregnant women and its consequences on a nationwide scale.

From the virtually complete and detailed drug-dispensing data, isotretinoin exposure could only be estimated since drug-dispensing data does not ascertain actual drug use and precise exposure intervals. However, patients coming for refills are usually taking their drug.

Spontaneous abortions before gestational age of 16 weeks and elective abortions were not included in our cohort and therefore our results probably underestimate the number of isotretinoin-exposed pregnancies and its consequences.

Specific teratogenic risks could not be estimated with data lacking information on pregnancies until 16 weeks of gestation and lacking detailed descriptions of adverse fetal and neonatal outcomes.

Introduction

Isotretinoin, a vitamin A derivative, is licensed in the European Union (EU) since 1983 and is indicated for systemic treatment of severe acne (such as nodular or conglobate acne or acne at risk of permanent scarring) in patients resistant to adequate courses of standard therapy with systemic antibacterials and topical therapy.1 The teratogenic potential is an important characteristic of isotretinoin. Animal studies already suggested teratogenic effects in humans and isotretinoin has been contraindicated for use during pregnancy since the very beginning of the marketing authorisation. Despite this contraindication, the first cases of congenital anomalies after isotretinoin use during pregnancy were documented already in 1983.2 As described by Lammer et al3 in 1985, isotretinoin embryopathy consists of craniofacial, cardiac, thymic and central nervous system defects. They found a relative risk of 26 for this group of major congenital malformations after systemic isotretinoin exposure during some parts of the first 10 weeks after conception.3 Elective termination of pregnancy (ETOP) was decided in more than 50% of exposed pregnancies and 20% of the remaining pregnancies ended in a first trimester spontaneous abortion.3 Reports of congenital anomalies after isotretinoin use accumulated and consequently, in 1988 the marketing authorisation holder of isotretinoin implemented a world-wide Pregnancy Prevention Programme (PPP) to better prevent pregnancies among systemic isotretinoin users.4 The PPP included an educational programme for prescribers and patients including material to be used in counselling women about the need to prevent pregnancy while taking isotretinoin. Conditions for prescribing included a negative pregnancy test, the use of reliable contraception and a signed patient consent form.4 In 2003, a review of isotretinoin by the European Medicine Agency (EMA) resulted in a compulsory European harmonised PPP for all isotretinoin containing products.1 The elements of the European wide PPP are listed in box 1.

Box 1. Elements of the European Union isotretinoin pregnancy prevention programme.

1. Isotretinoin is contraindicated in pregnant women and should only be initiated in women of reproductive age who understand the teratogenic risk and the need for regular follow-up.

2. Use of effective contraceptive measures from 4 weeks before isotretinoin initiation until 4 weeks after treatment discontinuation. At least one and preferably two complementary forms of contraception including a barrier method should be used.

3. Pregnancy testing should be performed before, during and 5 weeks after discontinuation of isotretinoin.

4. Isotretinoin should only be prescribed by or under the supervision of a physician with experience in the use of systemic retinoids.

5. Prescription should be limited to 30 days of treatment and continuation of treatment requires a new prescription.

6. Dispensing of isotretinoin should occur within a maximum of 7 days after prescription.

7. Educational programmes for healthcare professionals including prescribers and pharmacists, and patients are in place to inform them about the teratogenic risk and to create awareness of the pregnancy prevention programme.

The safe use of isotretinoin in women of reproductive age is in the interest of public health because of the potential risk of spontaneous and elective abortions, and, more importantly, children with major congenital anomalies require continuous healthcare throughout their life. Although a PPP has been implemented in the EU, pregnancies during isotretinoin therapy still occur.5 6 The regulatory authorities of 16 EU member states responded in 2009 to a survey that isotretinoin exposed pregnancies have occurred in their country.7 A French study between 2003 and 2006 estimated a pregnancy rate from 0.4 to 1.2/1000 female isotretinoin users within reproductive age.6 Studies in the Netherlands observed that only 52–59% of the female isotretinoin users of reproductive age used concomitant hormonal contraceptives, which was higher than the 39–46% observed in the general female population of similar age, but lower than anticipated.8 9 Although these studies show limited compliance with the isotretinoin PPP, it is not known whether isotretinoin exposure also occurs during pregnancy and what the outcome of these pregnancies is. Therefore, the objective of our study was to estimate isotretinoin exposure in Dutch pregnant women despite the implemented PPP and second, to analyse the occurrence of adverse fetal and neonatal outcomes in these isotretinoin exposed pregnancies.

Methods

Data sources

For this population-based study a cohort of 203 962 pregnancies consisting of 208 161 fetuses was constructed using a linkage between the PHARMO Database Network and the Netherlands Perinatal Registry (PRN). The PHARMO Database Network is a dynamic population-based cohort including, among other information, drug-dispensing records from community pharmacies for more than 3 million individuals in the Netherlands (approximately 20% of the Dutch population) that are collected since 1986.10 The drug-dispensing data contain the following information per prescription: the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification of the drug, dispensing date, regimen, quantity dispensed and estimated length of duration of use.11 The PRN is a nationwide registry that contains linked and validated data from four databases: the national obstetric database for midwives (LVR-1), the national obstetric database for gynaecologists (LVR-2), the national obstetric database for general practitioners (LVR-h) and the national neonatal/paediatric database (LNR).12 The registry contains information about care before, during and after delivery as well as maternal and neonatal characteristics and outcome of 95% of 180 000 pregnancies annually in the Netherlands with a gestational age of at least 16 weeks. The PRN includes information on pregnancy outcome including congenital anomalies detected during pregnancy, at birth or within the first year after birth. The probabilistic linking method between PHARMO and PRN has been described in detail elsewhere but was generally based on the birth date of the mother and child and their postal zip codes.13 To be included in the cohort the mother should be registered in the community pharmacy database of PHARMO during the whole pregnancy. The date of conception was estimated based on the last menstrual period or ultrasound, as recorded in the PRN, and was truncated to full weeks.

Isotretinoin dispensings

All dispensings for systemic (oral) isotretinoin (ATC D10BA01) filled in community pharmacies by women included in our cohort within the 12 months period before or during pregnancy were extracted from the PHARMO Database Network. Considering a daily dosage of 0.5–1 mg/kg daily,1 isotretinoin prescriptions dispensed on the same day were assumed to be used simultaneously and therefore these dispensings were pooled and considered as one dispensing (eg, the prescriptions of a 10 and 20 mg tablets dispensed at the same time to reach a daily dosage of 30 mg). For each isotretinoin dispensing, the length of the dispensing was calculated by dividing the total number of prescribed units by the number of units (doses) to be taken per day. In case isotretinoin dispensings that were pooled together had different lengths, the length of the single dispensing with the longest duration was used. To assess compliance with the PPP, we calculated the proportion of dispensings that exceeded 30 days, which is the maximum length according to the EU PPP.

Drug exposure interval

For all pregnancies (N=203 962) with gestational age of at least 16 weeks included in the cohort, isotretinoin exposure was estimated based on isotretinoin dispensing data (ATC D10BA01) filled by the mother during the 12 months period before and during pregnancy. Exposure in person time (days) was calculated by dividing the total number of prescribed units by the number of prescribed units per day. Isotretinoin exposure periods were defined considering a possible overlap of isotretinoin dispensings. Gaps, isotretinoin free periods between two isotretinoin dispensings, were not permitted meaning that an isotretinoin exposure period ends once an isotretinoin free period was identified. Using the start and end date of the isotretinoin exposure period, the number of days exposed was estimated for the following exposure intervals: 30 days before conception, first 90 days of gestation (first trimester), day 90–179 of gestation (second trimester) and day 180—delivery (third trimester). In addition, the entire period 30 days before pregnancy until delivery as well as the period from 30 days before till the end of the first trimester were analysed separately.

Adverse fetal or neonatal outcomes

For each fetus (N=208 161), we determined whether adverse fetal or neonatal outcomes were reported. Adverse fetal or neonatal outcomes were defined as all intrauterine deaths ≥16 week of gestation and liveborn infants with major congenital anomalies. If possible, congenital anomalies were categorised into nine subgroups: abdominal wall and skin disorders; cardiovascular defects; defects in the digestive system; defects in the nervous system; musculoskeletal defects; respiratory defects; urogenital defects; multiple, syndrome or chromosomal anomalies; or other congenital malformations. As we were interested in adverse fetal outcomes potentially induced by maternal drug exposure, chromosomal anomalies were not considered as an adverse outcome in the analyses.

Analysis

Potential exposure to isotretinoin in the 30 days before or during pregnancy was calculated per 10 000 pregnancies for the aforementioned exposure intervals including their 95% CIs. The proportions of adverse fetal outcome among isotretinoin exposed and unexposed fetuses or neonates were calculated including their 95% CIs. We used multiple logistic regression models to calculate ORs and 95% CIs to estimate associations between adverse fetal or neonatal outcome and maternal isotretinoin exposure. We adjusted for maternal age at conception (<20, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, ≥35), and if possible also for calendar time (year of conception) and gender of the infant. Analyses for specific congenital anomalies were performed when >3 cases were observed. The t test or Fisher exact test was used to derive p values when comparing continuous or categorical variables between study groups. Statistical significance was assumed for two-sided p values <0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS V.9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Between 1 January 1999 and 1 September 2007 in the Netherlands, a total of 203 962 pregnancies corresponding to 208 161 fetuses (including multiple births) were included in our study. The mean maternal age at conception was 30.3 years (SD 4.6) and mean duration of pregnancy was 39 weeks and 3 days (SD 19 days).

Isotretinoin dispensings

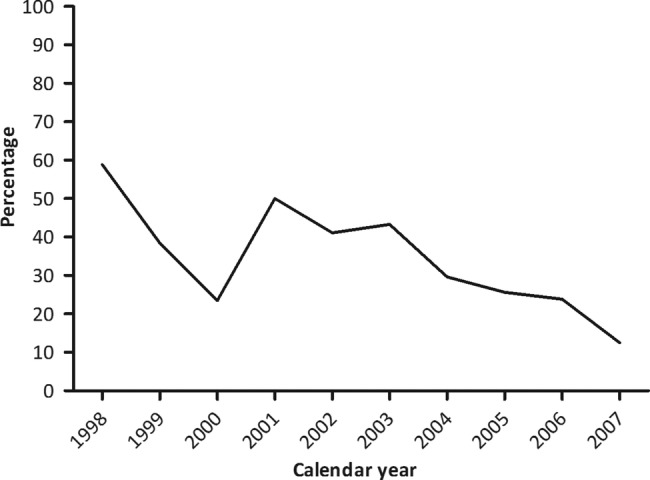

A total of 416 isotretinoin dispensings to 130 of the 203 962 women in the 12 months period before or during pregnancy were identified. In 139 of the 416 isotretinoin dispensings (33.4%), the dispensing consisted of >30 days of isotretinoin use. Figure 1 shows that the percentage of isotretinoin dispensings in the year before or during pregnancy exceeding the maximum duration of 30 days decreased over calendar time from 50% in 2001 to 13% in 2007.

Figure 1.

Percentage of isotretinoin dispensings exceeding the maximum duration of 30 days by calendar year.

Isotretinoin exposed pregnancies

Demographics for isotretinoin exposed and unexposed pregnancies are presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Description of the study population

| Isotretinoin exposed* | Isotretinoin unexposed | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnancies (N=203 962) | 51 | 203 911 | |

| Mean (±SD) maternal age at conception in years (95% CI) | 29.1 (4.9) (27.8 to 30.5) | 30.3 (4.7) (30.3 to 30.3) | 0.56 |

| Mean (±SD) gestational age at delivery in weeks (95% CI) | 39 (25 days) (38 to 40) | 39, 3 days (19 days) (39, 3 days–39, 3 days) |

0.33 |

| Fetuses (N=208 161) | 53 | 208 108 | |

| Gender (boy %) | 47.2% (33.3–61.1) | 51.5% (51.3–51.7) | 0.53 |

| Maternal age at conception in years, N, column % | 0.37 | ||

| <20 | 2 (3.8%) | 4063 (2.0%) | |

| ≥20–25 | 7 (13.2%) | 22 144 (10.6%) | |

| ≥25–30 | 21 (39.6%) | 68 366 (32.9%) | |

| ≥30–35 | 14 (26.4%) | 81 581 (39.2%) | |

| ≥35 | 9 (17.0%) | 31 951 (15.4%) | |

| Gestational age at delivery in weeks, N, column % | 0.64 | ||

| <27 | 1 (1.9%) | 2198 (1.1%) | |

| 27–30 | 1 (1.9%) | 1167 (0.6%) | |

| 31–33 | 0 (0.0%) | 2008 (1.0%) | |

| 34–36 | 3 (5.7%) | 7126 (3.4%) | |

| 37–39 | 12 (22.6%) | 50 854 (24.4%) | |

| >39 | 36 (67.9%) | 144 755 (69.5%) | |

| Adverse fetal outcome, N; % (95% CI) | 5; 9.4% (1.3 to 17.6) |

9041; 4.3% (4.3 to 4.4) |

0.08 |

*In the 30 days before conception or during pregnancy.

Overall, 51 pregnancies, 2.5 (95% CI 1.9 to 3.3) per 10 000 pregnancies, were potentially exposed to isotretinoin in the 30 days before conception or during pregnancy, despite the implemented PPP. Forty-five pregnant women, 2.2 (95% CI 1.6 to 2.9) per 10 000 pregnancies, were estimated to be exposed to isotretinoin during pregnancy of whom 27 (60%) started isotretinoin treatment while already being pregnant. In 18 pregnancies (40%), the conception occurred during isotretinoin treatment. Six pregnancies were identified within 1 month after isotretinoin discontinuation and were estimated to be exposed only before conception. In 40 out of 203 962 pregnancies, 2.0 (95% CI 1.4 to 2.6) per 10 000 pregnancies, an isotretinoin prescription was filled during pregnancy and 32 pregnancies, 1.6 (95% CI 1.1 to 2.2) per 10 000 pregnancies, received isotretinoin more than once during pregnancy. The number of isotretinoin dispensings per pregnancy ranged from 1 to 7, with a median of 2.5. The estimated isotretinoin exposure per exposure interval is presented in table 2.

Table 2.

Potential isotretinoin exposed pregnancies per exposure interval

| Isotretinoin exposure interval* | Exposed pregnancies (N=203 962) | Exposed pregnancies per 10 000 pregnancies (95% CI) | Median number of days exposed per pregnancy (range) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30 days before conception (30 days period) | 23 | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.7) | 24 (3–30) |

| 1st trimester (90 days period) | 28 | 1.4 (0.9 to 2.0) | 31 (3–88) |

| 2nd trimester (90 days period) | 25 | 1.2 (0.8 to 1.8) | 57 (1–90) |

| 3rd trimester (90–103 days period) | 26 | 1.3 (0.9 to 1.8) | 62 (1–103) |

| During pregnancy (270 days period) | 45 | 2.2 (1.6 to 2.9) | 63 (3–236) |

| 30 days before or during pregnancy (300 days period) | 51 | 2.5 (1.9 to 3.3) | 63 (7–236) |

| 30 days before or during 1st trimester (120 days period) | 35 | 1.7 (1.2 to 2.4) | 32 (7–114) |

*Categories are not mutually exclusive but indicate the number of pregnancies exposed to isotretinoin during that exposure interval.

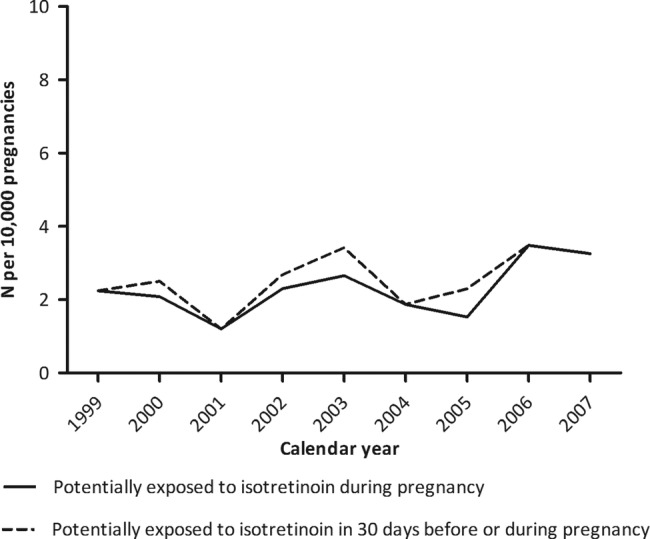

Among the pregnancies estimated to be exposed to isotretinoin during pregnancy (N=45), the number of exposed days during pregnancy ranged from 3 to 236 days with a median of 63 days. Figure 2 shows that the number of women estimated to be exposed to isotretinoin during pregnancy was the highest in 2006 with 3.5 pregnancies (95% CI 1.7 to 6.4) per 10 000 pregnancies.

Figure 2.

Isotretinoin exposed pregnancies per 10 000 pregnancies by calendar year.

Adverse fetal or neonatal outcomes

Independent of isotretinoin exposure, adverse fetal or neonatal outcomes were observed for 9046 of the 208 161 fetuses (4.4% (95% CI 4.3% to 4.4%)). The 51 pregnancies potentially exposed to isotretinoin in 30 days before conception or during pregnancy corresponded to 53 fetuses or neonates including two multiple births. Five of these, all singletons, had an adverse fetal or neonatal outcome (9.4% (95% CI 3.5% to 19.7%)). These included three intrauterine deaths and two liveborn infants with major congenital anomalies (see table 3). Among those potentially exposed during pregnancy only (N=47), 6.4% (95% CI 1.7% to 16.4%) had an adverse fetal or neonatal outcome. The OR for adverse fetal or neonatal outcome after potential isotretinoin exposure in the 30 days before or during pregnancy was 2.3 (95% CI 0.9 to 5.7) after adjustment for maternal age (see table 3). Restricting the analysis to the potential isotretinoin exposure during pregnancy, the adjusted OR of an adverse fetal outcome was 1.5 (95% CI 0.5 to 4.8). The number of cases was too low to allow for adjustments in addition to maternal age. The adjusted OR of any fetal or neonatal outcome was significantly increased at 3.6 (95% CI 1.4 to 9.4) for isotretinoin exposure during the 30 days before or first trimester of pregnancy.

Table 3.

ORs for adverse fetal and neonatal outcomes and isotretinoin exposure in 30 days before or during pregnancy

| Isotretinoin exposed fetuses | Exposed fetuses with adverse outcomes | OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR* (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| During pregnancy (N=47) | 3† | 1.5 (0.5 to 4.8) | 1.5 (0.5 to 4.8) |

| 30 days before or during pregnancy (N=53) | 5†‡ | 2.3 (0.9 to 5.8) | 2.3 (0.9 to 5.7) |

| 30 days before or 1st trimester (N=35) | 5†‡ | 3.7 (1.4 to 9.5) | 3.6 (1.4 to 9.4) |

*Maternal age in categories (<20, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, ≥35).

†Includes three intrauterine deaths.

1. In week 19, potentially exposed first 29 days following conception.

2. In week 35, potentially exposed 10 weeks following conception and from week 18 until week 32.

3. In week 38, also reported an unspecified septal defect; potentially exposed first 8 days following conception, during week 12 until week 24 and during week 28 until week 38.

‡Includes two liveborn infants with major congenital anomalies.

1. Neural tube defect, potentially exposed all 30 days before conception, not after conception.

2. Major congenital anomaly not further specified, potentially exposed the first 15 days of the 30 days before conception, not after conception.

Discussion

This study shows that 2 per 10 000 pregnancies were exposed to isotretinoin despite the PPP which is implemented to prevent isotretinoin use during pregnancy. Although this study was not intended to estimate the teratogenic risks of isotretinoin, adverse fetal and neonatal outcomes potentially related to isotretinoin exposure were observed. That there are still women who are using isotretinoin during pregnancy despite the implementation of the PPP is of major concern. Especially since the majority of isotretinoin exposed women (60%) were already pregnant at the time of first isotretinoin prescription and it seems that pregnancy was not always excluded before isotretinoin dispensing (box 1). These exposed pregnancies could probably have been prevented when appropriate pregnancy testing would have been performed. Furthermore, it was earlier demonstrated that women of reproductive age treated with isotretinoin did not always use effective contraceptive measures because only up to 59% of these women concomitantly used hormonal contraceptives.8 9 Limited compliance with the PPP was also observed in a survey among Dutch pharmacists which indicated that in 2007 and 2011, 44% and 49% of pharmacists, respectively, checked the use of contraception at every isotretinoin dispensing.14 The percentage of pharmacists that asked for negative pregnancy tests was stable with 15% and 16%, respectively, and is in line with our study which demonstrated that pregnancy is not always excluded before initiating isotretinoin and result in isotretinoin exposed pregnancies that could have been prevented. Our study showed that compliance with the recommended maximum length of prescription of 30 days was limited since one-third of isotretinoin dispensings exceeded 30 days which however decreased from 50% in 1999 to 13% in 2007. Based on these results it is clear that compliance with the PPP in the Netherlands between 1999 and 2007 was incomplete. These findings suggest an ongoing need to educate healthcare professionals and patients on the fetal risks of isotretinoin and the PPP, especially since isotretinoin is mostly used in young women of reproductive age.

Previous studies on isotretinoin use during pregnancy in other Western countries showed comparable results indicating that limited compliance to the PPP is not restricted to the Netherlands.6 15–17 In the USA, the most recent isotretinoin PPP, called iPLEDGE, has been implemented since 2006 and is stricter than the EU PPP. iPLEDGE is an internet-based system that requires registration of all stakeholders with monthly updates on prescription, pregnancy tests, contraceptive use and acknowledgement of risks.17 The pregnancy rate among isotretinoin users in the USA with the iPLEDGE PPP was estimated at 2.7/1000 treatment courses and did not change compared to the previous PPP called SMART (System to Manage Accutane-Related Teratogenicity) while only small improvements in compliance with contraceptive measures were observed.17 18 Apparently, also iPLEDGE does not bring complete security because further restrictive measures as in iPLEDGE do not seem to improve the results and may add unnecessary burden to the healthcare system since healthcare professionals and patients need to register and verify information on a monthly basis.4

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

A strength of this study is that we used a population-based design including virtually complete and detailed drug-dispensing data and pregnancy outcome data of a large cohort, which enabled estimating nationwide isotretinoin exposure rates among pregnant women. A known limitation of using drug-dispensing data is that it does not confirm the actual use of the drug under study and does not provide information on the precise time window of drug use. In addition, it is likely that women may change or stop their medication use when they become aware of pregnancy. However, it should be noted that our data show that the majority (80%) of pregnant women who filled prescriptions for isotretinoin came back for refills, suggesting that they really used the drug.

This study provides no information on spontaneous abortions that occurred until gestational age of 16 weeks and ETOPs because these data are not captured in the PRN database and these pregnancies were thus not included in our cohort. This resulted in an underestimation of the number of pregnancies that were potentially exposed to isotretinoin in the 30 days before or during pregnancy and the adverse fetal and neonatal outcomes. Studies that estimated the teratogenic risk of isotretinoin using prospectively documented isotretinoin exposed pregnancies found much higher proportions of pregnancies resulting in spontaneous abortion, stillbirth or reported congenital malformations, that is, 36% (13 of the 36 fetuses)3 and 26% (6 of the 23 fetuses).5

Without detailed information on drug exposure preferably verified by the patient whether the drug was actually taken and detailed descriptions of the diagnosed fetal outcome as well as on spontaneous abortions, the teratogenic risk of isotretinoin could not be accurately estimated. With regard to the adverse fetal outcomes observed in our study, we cannot exclude that they had any other aetiology than isotretinoin exposure. Owing to the low number of cases it was also not possible to adjust in the statistical analysis for important confounding factors other than maternal age such as smoking, alcohol intake, previous pregnancy outcomes and exposure to other potentially teratogenic drugs. Detection bias may also have influenced the incidence and estimated risks of congenital anomalies since more detailed diagnostics might have been used in pregnancies exposed to isotretinoin compared to the unexposed pregnancies. Nevertheless, the results of our study are in line with the undisputed embryotoxicity of isotretinoin and suggestive of an increased risks of adverse fetal or neonatal events when isotretinoin is dispensed for use in the 30 days period before or during pregnancy.

Implications and future research

In the Netherlands, approximately 180 000 pregnancies are reported annually.19 When extrapolating the 2.2 (95% CI 1.6 to 2.9) per 10 000 women potentially exposed to isotretinoin during pregnancy to a national level, there would be 29–52 isotretinoin-exposed pregnancies per year yielding unnecessary risks for congenital anomalies and fetal deaths. Therefore, it is in the interest of public health to implement effective PPPs and improve these measures or their compliance as much as possible to reduce isotretinoin use during pregnancy to the lowest possible level.

With the present study only the period 1999–2007 has been evaluated. The past years in the Netherlands, the PPP is communicated to healthcare professionals via product information,20 national general practitioner standards on treatment of acne,21 drug prescription and dispensing systems,22 the website of the Dutch Medicines Evaluation Board23 and the common (national) literature on drug information.24 Furthermore, research on isotretinoin use in the Netherlands and the PPP is conducted and published in (inter)national scientific medical journals.7–9 14 25–28 Consequently, data after 2007 are needed to judge if attention for the isotretinoin PPP during recent years has improved the carefulness with which isotretinoin is prescribed and dispensed.

Conclusions

Although a PPP was implemented almost 15 years ago, we showed that there are still pregnancies exposed to isotretinoin in the Netherlands which could have been prevented if appropriate exclusion of pregnancy before isotretinoin initiation would have been performed. These findings from the Netherlands add to the evidence that there is no full compliance to the isotretinoin PPP in many Western countries. Given the limited success of iPLEDGE, the question is which further measures are able to improve compliance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Netherlands Perinatal Registry for providing access to their database and contribution to the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: IMZ, RR, LMAH, MCJMS and BHS contributed to the study design and the interpretation of the data. IMZ and LMAH collected and analysed the data. IMZ, RR, LMAH, RMCH, MCJMS, SMJMS and BHS participated in the development and critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content and provided final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: This study was supported by the Drug Safety Unit of the Dutch Inspectorate of Health Care.

Competing interests: LMAH and RMCH are employees of the PHARMO Institute. This independent research institute performs financially supported studies for government and related healthcare authorities and several pharmaceutical companies. MCJMS is leading a research group that sometimes conducts research for pharmaceutical companies.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.European Medicines Agency (EMA). Annex I of the Summary information on a referral opinion following an arbitration pursant to article 29 of directive 2001/83/EC for isotretinoin 2003. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Referrals_document/Isotretinoin_29/WC500010881.pdf (accessed 2 May 2013).

- 2.Rosa FW. Teratogenicity of isotretinoin. Lancet 1983;2:513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lammer EJ, Chen DT, Hoar RM et al. Retinoic acid embryopathy. N Engl J Med 1985;313:837–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abroms L, Maibach E, Lyon-Daniel K et al. What is the best approach to reducing birth defects associated with isotretinoin? PLoS Med 2006;3:e483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schaefer C, Meister R, Weber-Schoendorfer C. Isotretinoin exposure and pregnancy outcome: an observational study of the Berlin Institute for Clinical Teratology and Drug Risk Assessment in Pregnancy. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2010;281:221–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Autret-Leca E, Kreft-Jais C, Elefant E et al. Isotretinoin exposure during pregnancy: assessment of spontaneous reports in France. Drug Saf 2010;33:659–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crijns I, Straus S, Luteijn M et al. Implementation of the harmonized EU isotretinoin Pregnancy Prevention Programme: a questionnaire survey among European regulatory agencies. Drug Saf 2012;35:27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teichert M, Visser LE, Dufour M et al. Isotretinoin use and compliance with the Dutch Pregnancy Prevention Programme: a retrospective cohort study in females of reproductive age using pharmacy dispensing data. Drug Saf 2010; 33:315–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crijns HJ, van Rein N, Gispen-de Wied CC et al. Prescriptive contraceptive use among isotretinoin users in the Netherlands in comparison with non-users: a drug utilisation study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2012;21:1060–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herings RM, Bakker A, Stricker BH et al. Pharmaco-morbidity linkage: a feasibility study comparing morbidity in two pharmacy based exposure cohorts. J Epidemiol Community Health 1992;46:136–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) index with Defined Daily Doses (DDDs). http://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/ (accessed 4 Oct 2013).

- 12.Stichting Perinatale Registratie Nederland. Grote Lijnen 10 jaar Perinatale Registratie Nederland. Utrecht: Stichting Perinatale Registratie Nederland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Houweling LM, Bezemer ID, Penning-van Beest FJ et al. First year of life medication use and hospital admission rates: premature compared with term infants. J Pediatr 2013;163:61–6.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crijns I, Mantel-Teeuwisse A, Bloemberg R et al. Healthcare professional surveys to investigate the implementation of the isotretinoin Pregnancy Prevention Programme: a descriptive study. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2013;12:29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berard A, Azoulay L, Koren G et al. Isotretinoin, pregnancies, abortions and birth defects: a population-based perspective. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2007;63:196–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bensouda-Grimaldi L, Jonville-Bera AP, Mouret E et al. Isotretinoin: compliance with recommendations in childbearing women. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2005;132:415–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinheiro SP, Kang EM, Kim CY et al. Concomitant use of isotretinoin and contraceptives before and after iPledge in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2013;22:1251–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shin J, Cheetham TC, Wong L et al. The impact of the iPLEDGE program on isotretinoin fetal exposure in an integrated health care system. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011;65:1117–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stichting Perinatale Registratie Nederland. Grote Lijnen 1999–2012. Urecht: Stichting Perinatale Registratie Nederland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roaccutane Summary of Product Characteristics. http://db.cbg-meb.nl/IB-teksten/h10305.pdf (accessed 3 Jan 2014).

- 21.Smeets JGE, Grooten SJJ, Bruinsma M et al. NHG-standard acne. Huisarts Wet 2007;50:259–68. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Implementatie Bijzonder Kenmerk: ‘Let op zwangerschapspreventieprogramma’ in Z-index 2009. https://www.z-index.nl/g-standaard/beschrijvingen/functioneel/wijzigingen/mb/bijzondere-kenmerken/IR%20BK%20Zwangerschapspreventieprogramma%20V-1-1-1.pdf (accessed 3 Mar 2014).

- 23.College ter Beoordeling van Geneesmiddelen/Medicines Evaluation Board (CBG/MEB). Zwangerschapspreventie programmas (ZPP). http://www.cbg-meb.nl/CBG/nl/humane-geneesmiddelen/geneesmiddelenbew/zwangerschapspreventieprogramma/default.htm (accessed 3 Mar 2014).

- 24.Commissie Farmaceutische Hulp. Isotretinoïne: waarschuwingen en voorzorgen. Farmacotherapeutisch kompas. College van Zorgverzekeringen, 2007.

- 25.Crijns HJ, Straus SM, Gispen-de Wied C et al. Compliance with pregnancy prevention programmes of isotretinoin in Europe: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol 2011;164:238–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fledderus S. Zwangerschapspreventie bij teratogene middelen faalt. Medisch Contact 2012;48:2692. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manders KC, de Vries LC, Roumen FJ. Pregnancy after isotretinoin use. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2013;157:A6567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crijns HJ. Teratogene middelen: zwangerschapspreventie kan beter. 2012. http://www.pw.nl/nieuws/nieuwsberichten/2012/teratogene-middelen-zwangerschapspreventie-kan-beter (accessed 3 Mar 2014). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.