Abstract

Hispanic girls are burdened with high levels of obesity and are less active than the general adolescent population, highlighting the need for creative strategies developed with community input to improve PA behaviors. Involving girls, parents, and the community in the intervention planning process may improve uptake and maintenance of PA. The purpose of this article is to describe how we engaged adolescent girls as partners in community-based intervention planning research. We begin with an overview of the research project and then describe how we used Participatory Photo Mapping (PPM) to engage girls in critical reflection and problems solving.

Keywords: participatory photo mapping, community-based participatory research, empowerment, adolescent girls, physical activity

Introduction

Insufficient physical activity (PA) and excessive sedentary behavior contribute significantly to the high rate of obesity among Hispanic youth.1,2 Despite the well-known benefits of PA, Hispanic youth are less likely than non-Hispanic white youth to meet current PA guidelines.3 The prevalence of PA is lowest in girls from certain racial and ethnic minority groups.3 During adolescence, girls experience higher levels of inactivity and a steeper decline in PA than do boys.3

To date, interventions targeting low-income adolescent girls do not offer evidence of effect and few culturally-tailored interventions have been developed.4 Despite different developmental needs and activity interests of boys and girls, most PA interventions are not gender-specific.4 Of the few PA interventions targeting adolescent girls, most are school-based and show modest or inconclusive results.4–6 Relatively few PA interventions are tailored to specific subgroups of adolescents girls (e.g., ethnic minorities) or address multiple levels of influence (interpersonal, organizational, and community).6 Hispanics in low-income communities may have fewer recreational resources and live in unsafe neighborhoods limiting opportunities for PA.7,8 Parenting styles, perceptions, and behavioral norms may also influence the level of activity among Hispanics.9

Hispanic adolescent girls have high levels of obesity and are less active than the general adolescent population, 10,11 yet little research focuses on them, highlighting the need for creative, community-infused strategies to improve PA behaviors in this high-risk population. Involving girls, parents, and the community in the intervention planning process may improve uptake and maintenance of PA in Hispanic adolescent girls.

We describe in this article how we engaged adolescent girls and key community constituents in community-based intervention planning research for the Physical Activity Partnership for Girls (PG) study, which the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio Institutional Review Board approved. We provide an overview of the research project, describe how we used Participatory Photo Mapping (PPM) 12 to engage girls in critical reflection and problem solving, and discuss considerations for future community-based studies involving adolescents.

Overview of Physical Activity Partnership for Girls (PG) Project

PG aimed to build a strong community-academic partnership and assess community priorities and needs for PA promotion among Hispanic girls (ages 11–14) in Westside San Antonio, Texas. We used a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach to engage multiple community stakeholders to design, jointly, an intervention to increase moderate-to-vigorous PA (MVPA) and reduce sedentary behavior among Hispanic girls that could be offered and sustained through a youth-serving community organization and would incorporate low-cost, mobile, and wireless technology to promote health and connect youth to community resources. We implemented PG in four phases: Partnership Development, Formative Assessments, Intervention Planning, and Pilot Testing the Intervention.

Partnership Development

The community-academic partnership comprised two community organizations and two academic institutions. Partners included the Girl Scouts of Southwest Texas (GSSWT) that develop girls’ leadership and well-being; a grassroots organization with much experience serving Westside families; experts in electrical and computer engineering and health and kinesiology from The University of Texas at San Antonio; and experts in obesity prevention and health promotion in Hispanic communities from the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio (UTHSCSA). While the partners led the research process, we also established a Community Advisory Board (CAB) with stakeholders from Westside-serving agencies, such as schools, community organizations, PA providers, health/medical groups, and state agencies.

Formative Assessments

We conducted several assessments to understand the issue of girls and PA from the perspective of three constituencies: girls, parents, and CAB members. We conducted a media survey with Westside girls to examine their technology-use behaviors and assess the feasibility of incorporating low-cost, mobile, and wireless technology into a PA intervention.13 We utilized Participatory Photo Mapping (PPM), a place-based photography assessment method to elicit girls’ PA perspectives.12 We held focus groups to explore parents’ PA perspectives. CAB members participated in nominal group processes14 and an online survey of community agencies.

Intervention Planning

A community retreat initialized the intervention planning process. The academic and community research partners and CAB members planned and attended this retreat to promote interaction and collaboration and harness the knowledge and experiences of participants. Adolescent girls and parents who participated in formative assessments also attended. Assisted by an external facilitator, retreat attendees analyzed formative assessment findings, interpreted and explained the data, and identified solutions.

After sharing assessment data, the retreat transitioned to an interactive, small-group format in which participants discussed solutions to the retreat’s “big questions”: What can we do to make active lifestyles the easy choice for middle school girls?; How can we make it easy for our girls to choose physical activity over TV and video games?; and What can we do to make physical activity as routine as brushing teeth? After small-group discussions (See Table 1), participants returned to the plenary session to share findings. The retreat’s format provided a way to collaboratively review assessment findings and reflect upon them in a participatory way. All participants (community leaders, parents, girls, researchers) contributed and were heard, an essential aspect of community-based programming. The retreat’s collaborative exploration of girls’ PA behaviors highlighted subtle aspects of PA promotion among girls in the Westside that might otherwise have been missed by researchers. Retreat themes integrated into the PA intervention include: physical activities should be fun, widely available, convenient (minimizing transportation burden on parents), free, and involve friends.

Table 1.

Retreat themes, SCT constructs, and performance objectives (PO) of intervention

| Retreat Themes (selected) | SCT Construct | PO of Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| What Do Girls Like? • Fun games, • Competitions • Indoor activities |

Behavioral Capability (Knowledge & Skills) | Participate in at least 3 MVPA activities during troop meetings, including at least 1 activity that develops a new skill. |

| Ideas for Parents • Parents can exercise their influence/control • Motivate kids to be healthy |

Social Support | Parents facilitate girls’ attendance to troop meetings and encourage daughter to participate in a new PA events in the community. |

| Resources • Existing Resources-How do we connect girls? • Tennis courts-Motivate kids to learn, compete; need safe place to try new activities • Swimming pools-Host gender/age-specific programs; low cost classes |

Knowledge & Skills Reinforcement |

• Learn and practice new skills (e.g., archery, golf, Zumba) • Facebook posts with photos about intervention activities. • Activity passport recognized and rewarded girls’ participation in troop, family, and individual physical activities. |

| Role models for being active | Observational Learning (modeling) | Troop leaders trained to model positive PA behaviors. |

Using results from the community retreat and an intervention mapping approach,15 UTHSCSA and GSSWT staff worked collaboratively to develop Be Fit with Friends (BFF), a multi-component, culturally and environmentally relevant PA intervention for Hispanic girls. BFF integrated Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), proven behavior change strategies for girls, and promoted PA in the environmental context in which these girls live and play (See Table 1). The intervention focused on both the individual girl’s behavior and the social environment that impacts her behavior, in order to meet the behavioral outcomes of girls increasing MVPA and decreasing sedentary activity. For example, we utilized behavioral capacity to teach girls how to be physically active; retreat discussions suggested the context in which this should happen for this population (e.g., types of activities girls like, resources to support engagement in these activities). (See Table 1 for further information on retreat themes and SCT constructs for BFF).

Pilot Testing the Intervention

We pilot-tested BFF using a group randomized trial design to ascertain its feasibility and effects among Hispanic adolescent girls. We plan to fully describe the pilot intervention outcomes in a separate article.

In the next section, we describe engaging adolescent girls in the research process, specifically in the formative assessment and intervention planning phases, through their participation in PPM. We describe how the girls worked through each of these phases and explored PA through an ongoing process of observation, reflection, and action.

The Participatory Photo Mapping (PPM) Method

PPM utilizes participatory photography, photo elicitation interviews, and public participation geographic information systems to enable community-based research partnerships to produce shared practical knowledge about a topic of mutual interest.12 Participating community residents take photos, discuss the meaning behind the photos with facilitators, and subsequently produce a narrative. Using a portable global positioning system (GPS) device (QSTARZ BT-Q1300), the qualitative narratives and photos of community residents are linked to a specific location on a map. Dennis and colleagues12 describe PPM’s theoretical foundations (e.g., CBPR, principle of lived experience, participatory photography, community mapping).

Picture This!: Using PPM with Girls in a CBPR Project

We designed Picture This!, PG’s adaptation of PPM, to engage middle school girls from Westside San Antonio to help develop an intervention to increase their PA. UTHSCSA, in partnership with GSSWT, had primary responsibility for developing and implementing Picture This!. GSSWT, started in 1924 by the Girl Scouts of the United States of America, offers a variety of programs to 24,000 girls (ages 5–17) in 21 counties in South Texas.16 GSSWT established the Avenida Guadalupe Girl Scout Center (“Avenida”) in Westside San Antonio in 1993 to enhance its outreach efforts in underserved areas and provide culturally appropriate programs from within the community. GSSWT’s efforts to promote the health and well-being of girls, their initiatives focusing on PA promotion, and their sustained support through Avenida for outreach to Westside San Antonio made this organization an ideal partner.

GSSWT staff was responsible for: recruiting girls; recruiting and training facilitators; tracking project activities; and implementing Picture This! sessions with girls. UTHSCSA research staff was responsible for: developing the girls’ workbook and manual for the training facilitator; training the initial team of facilitators and girls; and quality control of project documentation. Picture This! consisted of seven sessions (See Table 2) facilitated by GSSWT staff. Facilitators provided meeting sign-in sheets, managed tracking logs for camera and GPS equipment, planned photo walking tour routes, and helped girls complete photo selection and recording forms.

Table 2.

Overview of Picture This! Sessions

| Session | Topic and Activity | Select Objectives |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction to Physical Activity and Picture This! | • Understand the importance of physical activity in their lives • Define the six step of Picture This! |

| 2 | Responsible use of the Camera | • Discuss the responsibilities of being a photographer to their subjects • Understand and discuss Safety Guidelines |

| 3 | Using Camera and Photography Skills | • Learn how to handle the camera • Practice using the camera |

| 4 | Photo Walking Tour | • Conduct walking tours of the surrounding neighborhood • Document observations, thoughts, and ideas using the Photo Recording Form |

| 5 | Photo Sharing | • Share the information from Form H: Photo Recording and photos with the troop • Discuss the photos selected and come to consensus on a caption or narrative |

| 6 | Creating a Photo Essay | • Develop commentary for selected photos for posters. • Discuss how students can share photos with community. |

Study population

San Antonio has 1.4 million residents, making it the second-largest city in Texas and seventh-largest in the U.S.17 Westside San Antonio is a historically underserved urban sector with more than 100,000 residents. About 96% of Westside residents are Hispanic; 53% do not have a high school diploma; median household income for 2010 was $26,400; and nearly half (49%) of the population lived below the poverty line as of 2013.17 Picture This! participants were middle school Hispanic girls ages 11–14 who were GSSWT members and lived in the area surrounding Avenida in Westside San Antonio. We did not use inclusion criteria based on health status (e.g., obese) or health behaviors (e.g., physically active) because we wanted input from all types of Hispanic girls. Girls received a free membership to Girl Scouts, a Picture This! t-shirt, opportunities to participate in free out-of-school programming (e.g., field trips), and participation incentives (e.g., gift bags). Forty girls (92.5% Hispanic and 7.5% non-Hispanic) participated intermittently throughout the entire program; out of these, nine teams of two to three girls each participated in photo walking tours and group sharing sessions, and 10 girls participated in the community retreat to present their work to community stakeholders.

Picture This! Structure

UTHSCSA research staff trained four GSSWT staff to facilitate Picture This!. The facilitator curriculum incorporated the look, think, act framework.18 The facilitator’s role was to help girls think critically and encourage positive group dynamics during sessions. Facilitators provided technical assistance regarding cameras, GPS, or other equipment; led girls in discussions about their photographs; and supported girls with designing posters to present their findings to community stakeholders.

The majority of sessions with girls occurred during scheduled meeting times (usually monthly) either after school or on weekends at Avenida or during the lunch period at two middle schools. Meetings were conducted at these times to limit scheduling conflicts with families. Picture This! activities took place from January to May 2010.

Picture This! sessions closely follow both the PPM process developed by Dennis et al12 and Photovoice by Wang and Burris19 and Royce et al20: defining the research issue, training project facilitators and adolescent girls, reflecting on initial themes for photos, photo walking tour, photo-sharing group discussion, creating a photo essay documenting stories, presenting findings to community stakeholders, and linking photos and narratives to a neighborhood map.

Defining the research issue

The PG investigative team defined the research issue—determine the most effective ways for promoting PA among adolescent girls—before initiating Picture This!. Although researchers defined the issue in advance of youth participation, girls were given the opportunity to conceptualize the problem in their own way. Facilitators asked girls to think about these “big questions” as they decided on photo selections: What helps girls your age be active?; What keeps girls your age from being active?

Training facilitators and adolescent girls

Facilitator qualifications included: GSSWT employment; passing a criminal background check; being a leader of a middle-school-aged Girl Scout troop in Westside San Antonio; and completing Picture This! training. To train the four Picture This! facilitators, UTHSCSA conducted three monthly trainings from January to March 2010, each lasting three hours. At the first training, UTHSCSA staff trained facilitators on sessions one through three (See Table 2) to prepare for the initial project kickoff event. The second training covered session four (See Table 2). Facilitators learned to map the walking route using Google Maps, practiced using the GPS devices and cameras by taking practice walks around Avenida, and learned to download and save photos and GPS data and prepare photos for photo sharing. The last training focused on sessions five through seven (See Table 2). Facilitators learned to ask open-ended question to foster discussion among the girls and record discussion notes. The facilitators also learned to use a digital photo service to help girls create their photo essays and narratives.

Facilitators trained the adolescent girls at two initial kickoff events held on a weekend day in January 2010, each lasting 2.5 hours (with 90 minutes of actual training content). We provided a morning and an afternoon training sessions to allow girls two opportunities to attend. At this event, facilitators covered sessions one through three (See Table 2) using interactive, hands-on activities to engage girls. After the kickoff event, adolescent girls met in teams with a facilitator for session four to five (See Table 2) either after school or on weekends at Avenida. These sessions were repeated as needed to formulate and document ideas. GSSWT sponsored a Spring Break Camp at which staff helped girls create their photo essays (e.g., an album with photographs and narrative text) in March 2010. In April 2010, girls created poster versions of the photo essays for the retreat in early May 2010. Scheduling most Picture This! activities during school holidays provided dual benefits: the project benefited from girls spending extensive amounts of time completing research activities; parents benefited from their daughters participating in supervised, out-of-school enrichment activities.

Each girl received a Picture This! Workbook to guide them through the six steps of Picture This!: take photos that answer the “big questions” during the photo walking tours; record photographs taken; keep a journal of thoughts, ideas, and impressions; create a photo essay (album and poster) that displays and describes the photos; meet with facilitators for discussions; and exhibit photo essays (poster) at PG’s community retreat. The workbook contained copies of forms which were needed to complete the project. UTHSCSA and GSSWT provided all supplies for each session, including handouts, Nikon camera with memory card, keychain GPS device (QSTARZ BT-Q1300), and resources for creating photo essays on an online digital photo service (e.g., Shutterfly) , and on poster boards. Except for GPS devices, all project supplies became the property of GSSWT.

During the kickoff event, facilitators first led the girls in a discussion exercise to explore PA and what it means to them. Facilitators asked girls to think about where they live, and how they live, and then list three things they were proud of and three things that needed to change in order to be more physically active. UTHSCSA trained facilitators to encourage girls to think broadly. Girls could consider PA for themselves personally, and expand their thinking to include their own living space and other people, settings, and places. Girls shared their ideas in a small group with their GSSWT facilitator.

Next, facilitators trained girls about safety guidelines for photo walks, being a responsible photographer, and respecting the rights and privacy of others to minimize risk to the girls. Girls practiced talking to people when taking photos and using photo consent forms. Consent was not needed for photos of crowds or cases in which the subject(s) could not be identified. Girls also learned about basic camera use and photography skills. The workbook included photography tips for easy reference. In addition, facilitators taught girls how use a photo recording form that helped girls document important information about each photo.

Photo walking tour

Facilitators planned and mapped walking routes before walking tours with the girls. We used pre-determined walking routes because of the girls’ ages and possible neighborhood dangers. Every team walked a different route. Before starting, facilitators reviewed the list of themes introduced at the kickoff event, the safely guidelines, and photo consent forms. Girls walked in self-selected teams of two to three persons with a facilitator. Girls decided which team members would take photos, record information on the photo recording forms, and collect consent forms. Facilitators encouraged girls to take turns so each team member could try each role. Facilitators provided brief instructions on camera use and basic photography tips. They assigned and distributed a camera and GPS device to each team. Facilitators reminded girls that the camera and GPS device assigned to each team must stay together (e.g., no sharing/trading of equipment between groups) because if the GPS device were separated from the camera, the photos taken by the girls would not be linked to a map.

The teams of girls walked the route and took photos in response to the aforementioned “big questions.” UTHSCSA staff trained facilitators to let the girls lead and explain the meaning of the photos they took instead of suggesting interpretations. Immediately following the photo walking tours, the teams of girls viewed their photos and selected one to three photos to discuss at the photo-sharing session. Facilitators instructed teams about completing photo selection forms. Facilitators downloaded all photos from the cameras and used the form to identify photos to either print or add to a PowerPoint presentation for the group discussion (session five).

Photo sharing group discussion

The photo-sharing session began with a general discussion of the girls’ photo walking tour experiences. Next, each team shared one or two photos with the larger group. The number of girls present at the session determined the number of photos discussed and the amount of time given to each team to talk about their photos. Girls used information from their photo recording forms to present their thoughts and reason(s) for taking the photo. Facilitators used the SHOWED (S-What is Seen here?, H-What is really Happening?, O-How does this relate to Our lives?, W-Why are things this way?, E-How could this image Educate People or change the way we think?, and D-What can I Do about it?) debriefing model to guide girls’ discussions of their photos and help girls recall their thoughts when taking the photo.21 UTHSCSA research staff trained facilitators to ask open-ended questions and document girls’ comments on a notepad, dry-erase board, or notes section of the PowerPoint presentation. The facilitator’s main goal was to help the girls reach a consensus on a caption or narrative for the photo(s) discussed. After each team shared their photos, the larger group discussed ideas for other photos to take on the next photo walking tour. Facilitators repeated both the photo walking tour and photo-sharing sessions as needed.

Creating a photo essay (album and poster) documenting stories

Girls created photo essays at a Spring Break Camp. Each team, assisted by a facilitator, used a digital photo service to create these essays (albums). Facilitators instructed teams to choose photos they believed were important for answering the aforementioned “big questions.” Girls had access to their photos from the photo walking tours and their photo recording forms. Staff did not impose limits on girls’ album creativity. In April 2010, girls prepared poster versions of their albums for the retreat.

Presenting the photo essay (posters) to community stakeholders

In the last step of Picture This!, girls shared photo essay posters with community stakeholders during a poster exhibit at the PG community retreat in May 2010. During a specific time on the retreat agenda, girls stood near their poster displays as community stakeholders visited and informally spoke with the girls about the posters. All girls in attendance received certificates of recognition at the opening of the retreat for participating in Picture This!. During the assessment data-sharing portion of the retreat, a representative from GSSWT and two girls who participated in the project shared a summary of the findings with community stakeholders at the retreat (See Table 3).

Table 3.

General Themes Derived from Picture This!

Centered on the physical environment and safety

|

Girls also participated as equals with adult community stakeholders, parents, and researchers in the retreat. Girls’ participation in Picture This! empowered them to confidently discuss the “big questions” with adults and actively participate in the community retreat. Girls realized through the process that the retreat’s adult participants valued their contributions and wanted to hear what they had to say.

Linking the photos and narrative to a map of the neighborhood

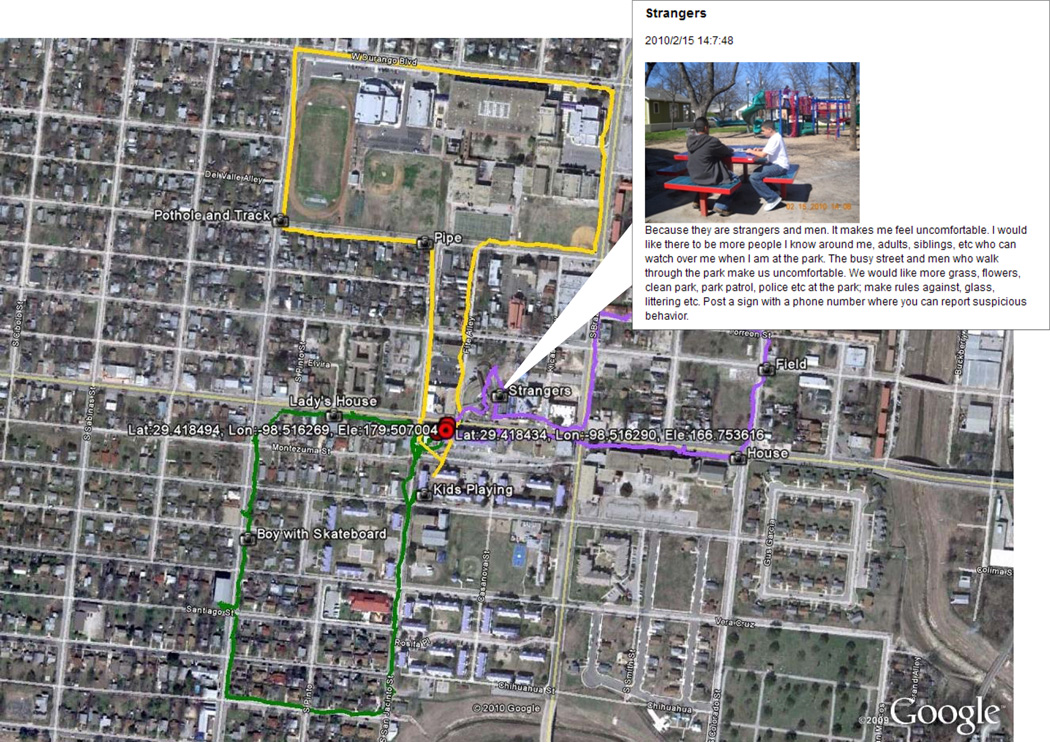

The first author linked the girls’ photos and narratives to a map of the Westside San Antonio neighborhood surrounding Avenida (See Photo 1). The keychain GPS device (QSTARZ BT-Q1300) utilized by girls during the photo walking tours provided photo mapping software (e.g., Travel Recorder) that integrates with Google Maps. By syncing the GPS devices with the digital camera’s photo stamping feature, the software: outlines the girls walking routes (e.g., green, yellow and purple colored lines); links the actual photos taken on the route (e.g., camera icons); and attaches a narrative to each photo in the map (e.g., clicking on the photo allows a narrative to be typed or displayed). The example (See Photo 1) displays three walking routes and illustrates one groups’ photo, “Strangers.” The girls’ narrative states: “Because they are strangers and men. It makes me feel uncomfortable. I would like there to be more people I know around me…who can watch over me when I am at the park. The busy street and men who walk through the park make us uncomfortable….”

Photo 1.

Example of final project produced by the Participatory Photo Mapping Method.

Considerations for Future Studies

Picture This! gave girls the opportunity to not only have their voices heard by researchers and community stakeholders involved in youth programming, but also be recognized publicly for their contribution to the PG intervention planning process. Picture This! offered girls a creative, empowering method to think critically about and investigate the “big questions”: “What helps girls your age be active?” and “What keeps girls your age from being active?” The PPM method allowed girls to contribute to the research process by offering interactive, hands-on activities to express their PA ideas. Girls had fun taking photos, assembling photo essays (album and poster), and owning the entire process. Picture This! incorporates the following features of critical youth empowerment programs:22 opportunity to critically reflect on an issue in a safe environment; preparation for confidently participating in retreats with adults; and confidently voicing their perspectives, which were used to affect change and publicly acknowledged. This participatory research approach integrated individual and community-level empowerment, benefitting both the individual girls and the community program.22

We encountered several challenges in Picture This!, which included a lack of traditional Girl Scout troops in the project area, retaining girls for the project’s duration, and technical difficulties with equipment. The UTHSCSA research team worked with GSSWT to recruit Westside girls, which proved more challenging because the Westside community had few traditional Girl Scout troops. Traditional troops have an established volunteer leader and meet regularly at a set time each month. However, girls in Westside troops “drop in” when they can, GSSWT staff lead activities (not volunteers), and troops have no set meeting times. To accommodate, GSSWT typically held events on weekends to engage girls and Girl Scout troop meetings during lunchtime at two local middle schools.

Retaining girls also proved difficult. Due to the non-traditional troop meeting format in the research target area, girls did not attend Picture This! sessions consistently (e.g., weekly meetings). We adapted by staging events, such as the initial kickoff and Spring Break Camp, to motivate participation. Middle school girls also had competing commitments, such as after-school activities, sports, and homework that may have limited their time and thus attendance. Due to this intermittent participation, facilitators provided an overview of the previously covered material at the start of every session and an orientation to the content of the current session. While we hoped to engage 60 girls in PPM, our actual enrollment was 40, 10 of which were engaged throughout the process and presented at the community retreat. We suggest improving retention in future studies by providing transportation from school to the center hosting the Girl Scout event, holding activities during school holidays, and hosting activities that include parent and child participation.

We also experienced technical difficulties with camera and GPS equipment. GSSWT staff facilitators sometimes forgot to turn on or charge the GPS devices, set the cameras with the time stamp, insert photo memory cards, and keep the GPS device and camera together during the walk. Technology has advanced in just the few years since we conducted Picture This!. Cell phones and cameras with internal GPS systems are now readily available and more affordable. Using an integrated data-capture system that records images and maps them geographically will minimize complexity and logistic barriers to implementing PPM.

Conclusion

This article described how we engaged Hispanic adolescent girls, key community constituents, as partners in community-based intervention planning research. Unlike more traditional qualitative methods (interviews, focus groups), Picture This! actively engaged adolescents girls in research. PPM demonstrated its legitimacy as a method for eliciting girls’ perceptions about PA, while simultaneously empowering girls to have their voices heard and stimulate change. Participation provided them new insights into better understanding their community and the issue of increasing PA among girls their age.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted with funding from the National Institute for Minority Health and Health Disparities (R24 MD 005096). We want to thank the following people for their contributions to the manuscript: Dr. Sam Dennis for his help adapting the Participatory Photo Mapping method for Picture This!; the Girls Scouts of Southwest Texas for Picture This! participant recruitment, program planning, and coordination; and Dr. Velia Leybas Nuño for facilitating the retreat where Picture This! participants presented their projects to community stakeholders.

Contributor Information

Daisy Y. Morales-Campos, Institute for Health Promotion Research, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, 7411 John Smith Drive, Suite 1000, San Antonio, Texas 78229, moralescampo@uthscsa.edu.

Deborah Parra-Medina, Institute for Health Promotion Research, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, 7411 John Smith Drive, Suite 1000, San Antonio, TX 78229, parramedina@uthscsa.edu.

Laura A. Esparza, Institute for Health Promotion Research, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, 7411 John Smith Drive, Suite 1000, San Antonio, TX 78229, EsparzaL@uthscsa.edu.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA. 2006;295:1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Research Council. Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance – United States, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:1–131. [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Sluijs EM, McMinn AM, Griffin SJ. Effectiveness of interventions to promote physical activity in children and adolescents: systematic review of controlled trials. BMJ. 2007 Oct 6;335:703–716. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39320.843947.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Webber LS, Catellier DJ, Lytle LA, et al. Promoting physical activity in middle school girls: trial of activity for adolescent girls. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(3):173–184. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Camacho-Minano MJ, LaVoi NM, Barr-Anderson DJ. Interventions to promote physical activity among young and adolescent girls: a systematic review. Health Educ Res. 2011;26:1025–1049. doi: 10.1093/her/cyr040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore JB, Hanes JC, Jr, Barbeau P, et al. Validation of the physical activity questionnaire for older children in children of different races. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2007;19:6–19. doi: 10.1123/pes.19.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.García R, Strongin S. [Accessed July 31 2014];Healthy parks, schools, and communities: Mapping green access and equity for Southern California. The City Project. http://www.mapjustice.org/socal. Published 2011.

- 9.Arredondo EM, Elder JP, Ayala GX, et al. Is parenting style related to children's healthy eating and physical activity in Latino families? Health Educ Res. 2006;21:862–871. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fryar CD, Carroll MD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of Obesity Among Children and Adolescents: United States, Trends 1963–1965 Through 2009–2010. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Stastics; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, et al. Prevalence of high body mass index in US children and adolescents, 2007–2008. JAMA. 2010;303:242–249. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dennis SF, Jr, Gaulocher S, Carpiano RM, et al. Participatory photo mapping (PPM): exploring an integrated method for health and place research with young people. Health Place. 2009;15:466–473. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mojica CM, Parra-Medina D, Yin Z, et al. Assessing media access and usea Latina adolescents to inform development of a physical activity promotion intervention incorporating text messaging. Health Promot Pract. 2013;15:548–555. doi: 10.1177/1524839913514441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed July 31 2014];Gaining Consensus Among Stakeholders Through the Nominal Group Technique. http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/evaluation/evaluation_planning.htm. Published November 2006.

- 15.Bartholomew LK, Parcel GS, Kok G, et al. Planning Health Promotion Programs: An Intervention Mapping Approach. 3rd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Girl Scouts of Southwest Texas. Girl Scouts of Southwest Texas 2013 Annual Report. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bexar County Health Collaborative. Bexar County Community Health Assessment. 2013. [Accessed July 31 2014]. http://healthcollaborative.net/2013BCCHA/index.html. Published August 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stringer ET. Action Research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang C, Burris MA. Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24:369–387. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Royce SW, Parra-Medina D, Messias D. Using photovoice to examine and initiate youth empowerment in community-based programs: a picture of process and lessons learned. Calif J Health Promot. 2006;4:80–91. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Minkler ME, Wallerstein NE. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jennings LB, Parra-Medina DM, Hilfinger-Messias DK, et al. Toward a critical social theory of youth empowerment. J Community Pract. 2006;14:31–55. [Google Scholar]