Abstract

Objective:

Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI), the deliberate, self-inflicted damage of bodily tissue without the intent to die, is associated with various negative outcomes. Although basic and epidemiologic research on NSSI has increased during the last 2 decades, literature on effective interventions targeting NSSI is still emerging. Here, we present a comprehensive, systematic review of existing psychological and pharmacological treatments designed specifically for NSSI, or including outcome assessments examining change in NSSI.

Method:

We conducted a systematic search of PsycINFO, MEDLINE, and ERIC databases to retrieve relevant articles that met inclusion criteria; specifically, uncontrolled and controlled trials that 1) presented quantitative outcome data on NSSI, and 2) clearly differentiated NSSI from suicidal self-injury (SSI). Consistent with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, definition of NSSI, we excluded studies examining populations with developmental or intellectual disabilities, or with psychotic disorders.

Results:

Several interventions appear to hold promise for reducing NSSI, including dialectical behaviour therapy, emotion regulation group therapy, manual-assisted cognitive therapy, dynamic deconstructive psychotherapy, atypical antipsychotics (aripiprazole), naltrexone, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (with or without cognitive-behavioural therapy). Nevertheless, there remains a paucity of well-controlled studies investigating treatment efficacy for NSSI.

Conclusions:

Structured psychotherapeutic approaches focusing on collaborative therapeutic relationships, motivation for change, and directly addressing NSSI behaviours seem to be most effective in reducing NSSI. Medications targeting the serotonergic, dopaminergic and opioid systems also have demonstrated some benefits. Future studies employing controlled designs as well as a clear delineation of NSSI and SSI will improve knowledge regarding treatment effects.

Keywords: nonsuicidal self-injury, treatment, psychotherapy, medication, intervention, systematic review

Abstract

Objectif :

L’automutilation non suicidaire (AMNS), c’est-à-dire les dommages délibérés et auto-infligés aux tissus corporels sans intention de mourir, est associée à divers résultats négatifs. Bien que la recherche basique et épidémiologique sur l’AMNS ait augmenté au cours des 20 dernières années, la littérature sur les interventions efficaces ciblant l’AMNS est encore naissante. Ici, nous présentons une revue systématique exhaustive des traitements psychologiques et pharmacologiques existants conçus spécifiquement pour l’AMNS, ou incluant des évaluations de résultats examinant le changement de l’AMNS.

Méthode :

Nous avons mené une recherche systématique dans les bases de données PsycINFO, MEDLINE, et ERIC pour extraire les articles pertinents qui satisfaisaient aux critères d’inclusion; spécifiquement, les essais incontrôlés et contrôlés qui 1) présentaient des données quantitative de résultats de l’AMNS, et 2) différenciaient nettement l’AMNS de l’automutilation suicidaire (AMS). En conformité avec la définition de l’AMNS du Manuel diagnostique et statistique des troubles mentaux, 5e édition, nous avons exclu les études qui examinaient les populations souffrant de déficiences développementales ou intellectuelles, ou de troubles psychotiques.

Résultats :

Plusieurs interventions semblent prometteuses pour réduire l’AMNS, dont la thérapie comportementale dialectique, la thérapie de groupe de régulation émotionnelle, la thérapie cognitive à l’aide d’un manuel, la psychothérapie dynamique déconstructive, les antipsychotiques atypiques (aripiprazole), le naltrexone, et les inhibiteurs spécifiques du recaptage de la sérotonine (avec ou sans thérapie cognitivo-comportementale). Néanmoins, il demeure que les études bien contrôlées sur l’efficacité des traitements de l’AMNS sont rares.

Conclusions :

Les approches psychothérapeutiques structurées axées sur les relations thérapeutiques de collaboration, la motivation de changer, et qui abordent directement les comportements d’AMNS semblent être les plus efficaces pour réduire l’AMNS. Les médicaments ciblant les systèmes sérotoninergique, dopaminergique et opioïde ont également démontré des avantages. Les futures études employant des méthodes contrôlées ainsi qu’une nette délimitation entre AMNS et AMS amélioreront nos connaissances sur les effets des traitements.

Research on how to effectively treat NSSI is urgently needed. Defined as the deliberate, self-inflicted destruction of body tissue without suicidal intent and for purposes not socially sanctioned,1 common forms of NSSI include self-cutting, burning, scratching, and self-hitting, with resulting injuries ranging from superficial wounds to severe and permanent mutilation. Recent efforts to address gaps in the current knowledge have culminated in the inclusion of NSSI in section III of the DSM-52 as a condition for future study, and emerging research3,4 supports this classification. This official recognition in the psychiatric nomenclature reflects the prominent and serious nature of the behaviour.

NSSI occurs in both clinical and nonclinical populations.5 Between 4% and 5.9% of adults in community samples have self-injured at least once in their lives.6,7 Rates of NSSI are notably elevated among younger people, including pre-adolescents (7.7%)8 and adolescents (13.9% to 35.6%).9–13 A recent study, using the suggested DSM-5 criteria, indicated that 6.7% of adolescents potentially qualify for a diagnosis of NSSI disorder.12 Prevalence estimates of NSSI in clinical populations range from 12% to more than 80% in psychiatric patients.14–17 Given that comprehensive reviews have documented the demographic, epidemiologic, and diagnostic features associated with NSSI,5,15 this information is not presented here.

Clinical Implications

Brief psychotherapeutic and pharmacological interventions can be effective for reducing NSSI.

It may be necessary to treat comorbid disorders before using medication to directly address self-injury.

Whenever possible, interventions that have been supported by level-1 evidence should be offered before trying other interventions.

Limitations

There is a dearth of well-controlled studies investigating treatment efficacy for NSSI.

Many treatment studies have relied on very small samples, possibly limiting generalizability of their findings.

Many treatment studies conflate operational definitions and measurement strategies of NSSI and SSI, obscuring knowledge regarding NSSI-specific outcomes.

Despite the clinical seriousness and prevalence of NSSI in medical and mental health settings, no current treatment for NSSI qualifies as empirically supported, efficacious, or well-established, according to criteria from the American Psychological Association Task Force18,19; see also Nock,5 Klonsky and Muehlenkamp,15 and Muehlenkamp.20 This relatively underdeveloped empirical base regarding treatment for NSSI is concerning, particularly as this behaviour is associated with various negative outcomes. One particular area of concern is the concurrent21–23 and prospective24,25 associations of NSSI with suicidal thoughts and behaviours. Between 55% and 85% of people with a history of NSSI also report suicidal behaviour,26,27 and higher frequencies of NSSI are associated with an increased risk of suicide attempts.28 Further, the overall functional impairment and psychopathology associated with NSSI is significant.4

Although NSSI and suicidal behaviour have similar behavioural features, several researchers have argued for the importance of a distinction between self-injury with and without suicidal intent.29–31 Acts of NSSI and SSI can be distinguished along several facets, including intention, frequency, medical severity, and methods.32–34 Additionally, NSSI characteristically occurs without suicidal ideation.7,35

Despite growing recognition that NSSI and SSI are distinct (albeit related) phenomena, most intervention studies focused on self-injury have used definitions and assessment methods that fail to differentiate between these behaviours. As a result, the target of treatment in these studies is often unclear.17 Terms such as parasuicide, deliberate self-harm, and self-injurious behaviour sometimes refer to NSSI and sometimes to a broader category of behaviours, including both SSI and NSSI. This lack of consistent terminology hampers comparability across studies, and makes it difficult to determine whether treatment results in changes in NSSI, SSI, or both.

Previous empirical treatment reviews typically have provided separate coverage of pharmacological and psychological treatments,20,36,37 and some are limited to particular (for example, adolescent)38,39 populations. These previous reviews highlight the following:

a lack of well-established pharmacological treatments for NSSI,36,37

a failure to maintain improvements on treatment termination,20,40 and

the lack of consistently superior outcomes for specific interventions, compared with TAU.5,39

However, to date, most reviews have included studies that conflate NSSI with SSI. Therefore, there is a pressing need for a current snapshot of the findings on treatments’ effects specific to NSSI.

Here, we provide a comprehensive, systematic review of the empirical literature on psychological and pharmacological treatments for NSSI in both adolescent and adult populations. Given the emerging nature of NSSI research, terminological clarity is essential for guiding appropriate assessment and intervention.33,41 As such, we employed a conservative definition of NSSI to ensure that our findings pertain specifically and uniquely to NSSI. Further, we evaluated the relative strength of support for various treatments to provide practical recommendations for clinical practice and research.

Method

Literature Search

We used MEDLINE, ERIC, and PsycINFO search engines to identify sources of interest. Search terms included one of the following: “self-injur*,” “self-harm*,” “self-mutilat*,” “self-wound*,” or “parasuicid*”; and one of the following: “intervention,” “*therapy,” “treatment,” or “medication.” We limited results to empirical or quantitative studies. To identify additional sources, we consulted reference lists of recent review articles investigating treatments for NSSI.5,17,20,36–40,42–51 Given the frequent co-occurrence of BPD and NSSI, we also screened published studies of psychotherapies that have garnered support in populations with BPD, including DBT, MBT, TFP, and SFT, by conducting literature searches in the same databases, and by examining a list of studies examining DBT compiled by Behavioral Tech, LLC.52

Inclusion and Exclusion

Studies were included in this review if they were published in the English language, included human subjects, presented quantitative outcome data on NSSI, used an uncontrolled (pre–post) or controlled-trial design, and clearly differentiated NSSI from SSI in the operationalization and measurement of NSSI. We excluded unsystematic clinical case reports, owing to potential bias and lack of experimental control. To maximize comprehensiveness, we included studies of treatments directly targeting NSSI, as well as those in which the treatment addressed other mental health problems (for example, depression and BPD), but outcomes related to NSSI were assessed. Consistent with the DSM-5 definition of NSSI,2 we excluded papers focusing on populations with developmental or intellectual disabilities, or with psychotic disorders. We also excluded articles focusing on acute care for NSSI (for example, wound care, and emergency department or psychiatric assessment). Finally, we excluded any study that conflated NSSI and SSI, including studies that operationally defined self-injury as including all acts of self-injury regardless of the behavioural intention, that employed one metric to assess both outcomes (for example, counts or rates that included but did not distinguish between these types of self-injury), or that used measures that failed to distinguish between NSSI and SSI (for example, the Overt Aggression Scale53).

Levels of Evidence

Once a preliminary set of articles had been identified, we categorized the level of evidence presented in each paper using the United States Preventive Services Task Force criteria.54 According to this schematic, level I evidence denotes having at least one well-designed RCT supporting a treatment’s possible efficacy. Level II-1 requires a well-designed controlled trial without randomization, level II-2 requires at least one well-designed cohort or case–control study, and level II-3 requires a multiple time series design. We excluded level III evidence (opinions of respected authorities based on clinical experience or descriptive studies) from our review.

Results

Search Results

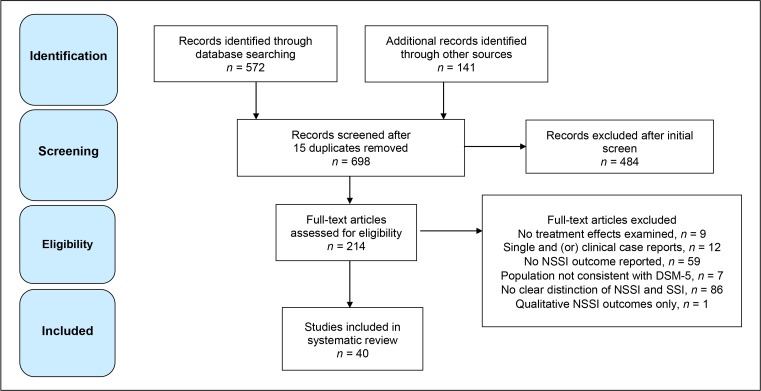

A flow chart diagramming our systematic review process is presented in Figure 1. Online eTable 1 summarizes results from the 40 unique studies (including 3 sets of 2 articles reporting on overlapping samples) included in this review.

Figure 1.

Flow chart depicting inclusion and exclusion process

Figure adapted from Moher et al108; the PRISMA Statement and the PRISMA Explanation and Elaboration document are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DSM-5 = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition; NSSI = nonsuicidal self-injury; SSI = suicidal self-injury

Levels of Evidence

We identified 15 sources that presented level I evidence, 3 that presented level II-1 evidence, 18 that presented level II-2 evidence, and 3 that presented level II-3 evidence.

Psychotherapy for Nonsuicidal Self-Injury

Empirical evidence was available for 6 types of psychotherapy: DBT, ERGT, MACT, TFP, DDP, and VMT. We excluded several studies of well-known, manualized treatments (for example, MBT and SFT) owing to consistent use of operational definitions or outcome measures that failed to clearly differentiate between NSSI and SSI.

DBT involves a combination of individual and group treatment, in addition to a therapist consultation team and the availability of therapists between sessions for coaching and assistance with effective skill use.55,56 DBT prioritizes reducing life-threatening behaviours, and several studies have demonstrated that DBT leads to greater reductions in NSSI and SSI (considered together), compared with TAU.57–60 We identified several empirical investigations of DBT (including 4 RCTs, 2 non-RCTs, and 10 uncontrolled trials) that distinguished NSSI from SSI in their outcome measures. However, results regarding the efficacy of DBT in treating NSSI have been mixed. Although uncontrolled trials generally suggest that DBT reduces rates, frequency, and urges to engage in NSSI,34,61–66 2 RCTs found that reductions in NSSI frequency were not statistically greater than those achieved in active control conditions.67,68 Conversely, however, 2 other RCTs demonstrated that DBT led to greater reductions in NSSI frequency than TAU.69,70 Regarding NSSI rates, whereas one RCT70 noted greater reductions in rates of NSSI in DBT, compared with TAU, another study did not detect any such differences.69 When reductions in NSSI are achieved during DBT, they are often sustained 6 to 12 months after treatment.67,69,70 Although we identified several uncontrolled studies investigating adaptations of DBT across various populations (for example, adolescents and patients with eating disorders) and settings (for example, inpatient and forensic), RCTs have thus far been limited to predominantly female adult outpatients with BPD. Thus it is unclear at this time whether the promising results achieved in uncontrolled trials of DBT are related to differences in the efficacy of DBT for NSSI across populations, or to differences in research designs, particularly given that controlled studies have used active treatment rather than wait-list control conditions. Investigations regarding potential mediators and moderators of treatment outcome for NSSI may help to clarify these contradictory findings. Currently, the available evidence suggests that while DBT confers considerable benefits in reducing BPD symptoms and associated psychopathology, findings are mixed on whether DBT outperforms active control conditions in the reduction of NSSI specifically.

ERGT is the only other psychotherapy that has been evaluated for its effects on NSSI in more than one controlled trial. Administered in a 14-week group format, ERGT focuses on the development of emotion regulation and acceptance skills, as well as on strategies to identify and pursue important goals and values.71 We identified 2 RCTs indicating that ERGT resulted in significantly greater reductions in NSSI frequency, compared with TAU.71,72 Further, 47% of the patients who received ERGT abstained from NSSI throughout a 9-month follow-up, supporting the durability of treatment effects.72 An uncontrolled ERGT trial also demonstrated significant reductions in NSSI frequency and increased rates of NSSI abstinence from pre- to posttreatment.73 All of the women in these clinical samples had a history of NSSI, and most (74% to 100%) met criteria for BPD.

Investigations of the other 4 psychotherapies reviewed (MACT, VMT, DDP, and TFP) are each limited to a single study; as such, confidence in their findings is contingent on further replication. MACT is a brief (typically 6 sessions), structured, problem-solving treatment, including individual therapy and bibliotherapy.74 Although MACT has been evaluated in 2 major RCTs,74,75 the outcome measures did not differentiate NSSI from SSI, and thus the studies were not included in our review. However, a smaller RCT indicated a significant advantage of MACT, compared with TAU, in reducing NSSI frequency among female adults with BPD.76

VMT is an integrated expressive arts therapy that aims to reduce emotion dysregulation and increase self-awareness via sound-making, singing, expressive writing, massage, movement, and drama activities.77 An uncontrolled, within-group, time-controlled trial suggested that female young adults engaged in less frequent NSSI while receiving 10 weeks of VMT, compared with during the 10-week pretreatment period.78 The diagnostic characteristics of this sample were not reported.

DDP is a manualized psychodynamic treatment for BPD patients with challenging co-occurring conditions that uses weekly individual sessions to increase clients’ capacity to describe affective and interpersonal experiences in coherent narratives.79 In a small RCT of adults with BPD and cooccurring substance disorders, in which only 7 participants reported engaging in NSSI prior to treatment, 3 (57.1%) reported abstaining from NSSI during the final 3 months of DDP.80 Moreover, among these participants, the frequency of NSSI within the final 3 months of DDP treatment was significantly less than the frequency in the 3 months prior to treatment.80 Unfortunately, comparisons of NSSI-related outcomes in the DDP and the control group were not carried out.

TFP is a psychodynamic treatment involving twice-weekly individual treatment using transference in relationships (therapeutic and other) as a vehicle for therapeutic change.81 Results from one uncontrolled trial of TFP for females with BPD indicated significant pre- to posttreatment reductions in the severity, but not frequency, of NSSI.82 Unfortunately, controlled studies of TFP83,84 did not meet our inclusion criteria, as NSSI was not clearly differentiated from SSI in these trials.

Pharmacotherapy for Nonsuicidal Self-Injury

Empirical evidence regarding psychopharmacological effects on NSSI was available for 5 drug classes: SSRIs (for example, fluoxetine), atypical antipsychotics (for example, aripiprazole and ziprasidone), SNRIs (venlafaxine), opioids (buprenorphine), and opioid antagonists (naltrexone).

Only 1 RCT has evaluated the efficacy of medication for reducing NSSI specifically, demonstrating that, among adults with BPD, more participants abstained from NSSI during treatment with aripiprazole and at the 18-month follow-up, compared with those receiving a placebo.85,86 Specifically, only 2 of the 26 patients engaged in NSSI during 8 weeks of aripiprazole treatment, and 4 engaged in NSSI during the 18-month follow-up (compared with 5 from the placebo group who engaged in NSSI during treatment, and 11 reporting NSSI during follow-up). Similarly, a non-RCT87 found that another atypical antipsychotic (ziprasidone) resulted in lower rates and frequency of NSSI in self-injuring adolescents, compared with alternative neuroleptic medications (for example, risperidone, olanzapine, chlorproxithen, and promethazine).

Regarding nonantipsychotics, a case-controlled, multiple-baseline trial showed that the rates and frequency of NSSI decreased significantly during augmentive naltrexone treatment in adults with BPD, compared with at baseline.88 Several uncontrolled trials have also reported benefits for venlafaxine, buprenorphine, fluoxetine, and naltrexone in reducing NSSI frequency and (or) increasing rates of NSSI abstinence,89–92 but replication with controlled designs is necessary to support these findings.

Combination Treatments for Nonsuicidal Self-Injury

Two RCTs have evaluated the incremental benefit of adding CBT to antidepressants (SSRI or SNRI) in treating adolescent major depressive disorder. Both studies concluded that adjunctive CBT did not reduce the likelihood of engaging in NSSI, compared with antidepressants alone,25,93,94 and may even increase risk for engaging in NSSI.93 Regarding the supplementation of CBT-oriented treatment with medication, one RCT evaluating DBT + olanzapine, compared with DBT + placebo, for women with BPD identified no incremental benefit of medication for reducing NSSI frequency.95

Comprehensive Therapeutic Programs for Nonsuicidal Self-Injury

Two uncontrolled studies have examined the effects of comprehensive treatment programs for adults with BPD or mixed personality disorders.96,97 These specialized programs included psychoeducation, pharmacotherapy, and group and individual therapy, and both incorporated DBT skills training as a component of treatment. Both studies detected significant reductions in rates of NSSI, postintervention (more than 50% and 17% to 25%, respectively).

Other Interventions for Nonsuicidal Self-Injury

Numerous studies have evaluated the effects of treatments that are not formalized as psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy. One recent RCT found that a structured postcard intervention following deliberate self-poisoning significantly reduced suicide-related outcomes; however, it did not reduce the rate or frequency of self-cutting.98 Likewise, one naturalistic follow-up study investigated brief (8 to 15 minutes), biweekly psychiatrist-facilitated assertiveness training sessions aimed at helping patients increase their self-acceptance and ability to calmly express their needs and desires. Among the 13 patients with BPD who were treated, 4 (30.7%) reported no NSSI during the final week following 1 to 4 years of treatment.99 Finally, one naturalistic, uncontrolled study reported that auricular acupuncture was associated with significant decreases in NSSI frequency among 9 depressed adolescents.100 Importantly, however, both of these uncontrolled studies were based on very small samples (n < 15).

Discussion

Our systematic review highlighted an emerging empirical literature pertaining to psychological and pharmacological interventions for NSSI, and identified several sources of evidence that have not been included in recent NSSI treatment reviews.17,38,39 We identified 15 RCTs—widely considered the gold standard in treatment research19—that evaluated NSSI treatment effects. Our results encourage cautious optimism regarding the possible efficacy of ERGT, MACT, atypical antipsychotics, and SSRIs for reducing NSSI. Additionally, we found that, although DBT is often associated with reduced rates and frequency of NSSI in uncontrolled trials and reduced rates of self-harm more generally (SSI and NSSI considered together), further research is necessary to substantiate its advantage over active control conditions for NSSI specifically.

Although we have provided a comprehensive picture of the current treatment research, more empirical work is required before we can confidently appraise the efficacy or effectiveness of NSSI interventions. Replication is particularly critical, as most of the treatments identified in this review have been investigated in a single study, by a single research team, using small samples and (or) using exclusively BPD samples. Nonetheless, we believe that this review can provide useful guidance for clinicians, as well as directions for future research.

While our results do not identify a clear front-runner treatment for NSSI, there are numerous commonalities among the treatments identified as potentially efficacious. Among psychotherapeutic treatments demonstrating benefits for NSSI, each stipulate that 2 preconditions for treatment are essential: a supportive, collaborative therapeutic relationship; and motivation for treatment.

Consistent with these principles, patients who perceived their therapist as warm and protecting reported fewer episodes of NSSI during the course of DBT.101 Second, and congruent with current theory suggesting that NSSI serves to regulate unwanted experiences,102 several psychotherapeutic approaches recognized as beneficial in this review incorporate skills acquisition, particularly in the domain of emotion regulation. Although mechanisms of change in treatments for NSSI remain largely unknown, some evidence indicates that the use of DBT skills may mediate a reduction in NSSI during the course of DBT.103 It is possible that the use of behavioural skills may similarly mediate the link between other interventions and reductions in NSSI. Third, many advantageous therapies incorporate idiographic functional assessments of the factors that precipitate and maintain NSSI, and directly monitor and target NSSI on an ongoing basis. Supporting these approaches, research has shown that adolescents presenting to emergency services with NSSI respond favourably to a specific, structured assessment strategy.104

Regarding pharmacological interventions, studies demonstrating the possible benefits of atypical antipsychotics, SNRIs, SSRIs, and naltrexone in reducing NSSI are consistent with neurobiological models implicating disruptions in the dopaminergic, serotonergic, and endogenous opioid systems in NSSI.36 However, conviction in the effectiveness of these medications must be moderated in light of the very small sample sizes for these medication trials. Some previous reviews have advised initially targeting disorders that co-occur with NSSI before using medication to directly address self-injury.36,105 Consistent with this recommendation, results of our review suggest that pharmacological treatment of a cooccurring disorder may reduce NSSI, at least in depressed adolescents.25,93,94 Unfortunately, there is a paucity of research on clinical decision making regarding which medication to try first, and (or) when psychotherapy should be preferred as a first-line treatment (however, see Plener et al36). This is an important domain for future research to address.

Encouragingly, our results suggest that reductions in NSSI can be achieved with treatments that are relatively brief in nature (ERGT: 14 weeks, MACT: 6 sessions, atypical antipsychotics: 8 weeks, and SSRI with and without CBT: 12 weeks), even among populations that are challenging to treat (for example, BPD and depressed adolescents). Moreover, some studies70,76 suggest that initial treatment effects may persist up to 6 months beyond termination. Although cost analyses specific to NSSI have not yet been pursued, treatments that attenuate inpatient admissions and emergency department visits are often cost-effective.58 Given that more than one-half of patients who present to the hospital following NSSI or SSI are hospitalized,106 the development of brief and effective interventions for NSSI holds considerable promise for reducing health care expenditures.

To our knowledge, this review is one of the first to systematically exclude treatment studies that have not clearly differentiated NSSI from SSI. As such, it provides an unambiguous picture of the state of treatment research for NSSI. In addition, this review underscores the pervasiveness of studies conflating NSSI and SSI in their operational definitions and measurement strategies. Nearly 40% of the full-text articles reviewed were excluded because a clear distinction between NSSI and SSI was not made. This highlights a crucial need for future studies to use clear operational definitions, as well as measures that disentangle SSI from NSSI. While many interventions demonstrating benefits for reducing broader classes of self-injury (NSSI and SSI) may also be effective for reducing NSSI specifically, research must directly address this possibility. It is our hope that the inclusion of NSSI disorder as a condition for further research in the DSM-52 will provide additional impetus for such work.

In addition to the use of consistent terminology, we believe 3 considerations are most essential as research on treatments for NSSI progresses. Of primary importance, studies must employ controlled, experimental designs that maximize internal validity to unequivocally demonstrate treatment efficacy in the absence of confounding factors, such as passage of time.19 Additionally, trials based on larger samples will improve statistical power, generalizability, and the ability to investigate mediators and moderators of treatment outcome. Finally, given that the preponderance of treatment research has been conducted in BPD samples (18 of the 40 studies reviewed here), it is essential to investigate treatment efficacy in other populations that exhibit high rates of NSSI, such as those with depression, anxiety, and (or) eating disorders.

Conclusions

Overall, our systematic review uncovered encouraging evidence of an emerging empirical literature investigating treatments effects for NSSI. Unfortunately, it also highlights systematic problems with terminology and nomenclature that make the literature on self-harm difficult to navigate. Fortunately, as the treatment literature on disorders such as BPD and depression have revealed,107 building scientific knowledge to guide treatment can occur relatively quickly once potentially effective therapeutic frameworks are formalized and subjected to empirical evaluation.

Acknowledgments

Work on this article was supported by a Canadian Institute for Health Research Canada Graduate Scholarship Doctoral Award to Ms Turner, and a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Career Investigator Award to Dr Chapman.

The Canadian Psychiatric Association proudly supports the In Review series by providing an honorarium to the authors.

Abbreviations

- BPD

borderline personality disorder

- CBT

cognitive-behavioural therapy

- DBT

dialectical behavioural therapy

- DDP

dynamic deconstructive psychotherapy

- DSM

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

- ERGT

emotion regulation group therapy

- MACT

manual-assisted cognitive therapy

- MBT

mentalization-based therapy

- NSSI

nonsuicidal self-injury

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- SFT

schema-focused therapy

- SNRI

serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor

- SSI

suicidal self-injury

- SSRI

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

- TAU

treatment as usual

- TFP

transference-focused psychotherapy

- VMT

voice-movement therapy

References

- 1.International Society for the Study of Self-Injury. Definition of non-suicidal self-injury [Internet] Bronx (NY): Fordham University; c2007. [cited 2014 Apr 5]. Available from: http://www.itriples.org/isss-aboutself-i.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Psychiatric Association (APA) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington (VA): APA; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glenn CR, Klonsky ED. Nonsuicidal self-injury disorder: an empirical investigation in adolescent psychiatric patients. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2013;42(4):496–507. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.794699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Selby EA, Bender TW, Gordon KH, et al. Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) disorder: a preliminary study. Personal Disord. 2012;3(2):167–175. doi: 10.1037/a0024405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nock MK. Self-injury. Ann Rev Clin Psychol. 2010;6:339–363. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Briere J, Gil E. Self-mutilation in clinical and general population samples: prevalence, correlates, and functions. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68(4):609–620. doi: 10.1037/h0080369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klonsky ED. Non-suicidal self-injury in United States adults: prevalence, sociodemographics, topography and functions. Psychol Med. 2011;41(9):1981–1986. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710002497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hilt LM, Nock MK, Lloyd-Richardson EE, et al. Longitudinal study of nonsuicidal self-injury among young adolescents: rates, correlates, and preliminary test of an interpersonal model. J Early Adolesc. 2008;28(3):455–469. doi: 10.1177/0272431608316604. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laye-Gindhu A, Schonert-Reichl KA. Nonsuicidal self-harm among community adolescents: understanding the “whats” and “whys” of self-harm. J Youth Adolesc. 2005;34(5):447–457. doi: 10.1007/s10964-005-7262-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muehlenkamp JJ, Gutierrez PM. An investigation of differences between self-injurious behavior and suicide attempts in a sample of adolescents. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2004;34(1):12–23. doi: 10.1521/suli.34.1.12.27769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ross S, Heath N. A study of the frequency of self-mutilation in a community sample of adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 2002;31(1):67–77. doi: 10.1023/A:1014089117419. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zetterqvist M, Lundh L-G, Dahlström Ö, et al. Prevalence and function of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in a community sample of adolescents, using suggested DSM-5 criteria for a potential NSSI disorder. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2013;41(5):759–773. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9712-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zoroglu SS, Tuzun U, Sar V, et al. Suicide attempt and self-mutilation among Turkish high school students in relation with abuse, neglect and dissociation. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;57(1):119–126. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1819.2003.01088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobson CM, Muehlenkamp JJ, Miller AL, et al. Psychiatric impairment among adolescents engaging in different types of deliberate self-harm. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2008;37(2):363–375. doi: 10.1080/15374410801955771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klonsky ED, Muehlenkamp JJ. Self-injury: a research review for the practitioner. J Clin Psychol. 2007;63(11):1045–1056. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nock MK, Prinstein MJ. A functional approach to the assessment of self-mutilative behavior. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(5):885–890. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Washburn JJ, Richardt SL, Styer DM, et al. Psychotherapeutic approaches to non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2012;6(1):14. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-6-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Psychological Association (APA) Criteria for evaluating treatment guidelines. Washington (DC): APA; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chambless DL, Hollon SD. Defining empirically supported therapies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66(1):7–18. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.66.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muehlenkamp JJ. Empirically supported treatments and general therapy guidelines for non-suicidal self-injury. J Ment Health Counsel. 2006;28(2):166–185. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andover MS, Gibb BE. Non-suicidal self-injury, attempted suicide, and suicidal intent among psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178(1):101–105. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lloyd-Richardson EE, Perrine N, Dierker L, et al. Characteristic and functions on non-suicidal self-injury in a community sample of adolescents. Psychol Med. 2007;37(8):1183–1192. doi: 10.1017/S003329170700027X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nock MK, Joiner TEJ, Gordon KH, et al. Non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: diagnostic correlates and relation to suicide attempts. Psychiatry Res. 2006;144(1):65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Asarnow JR, Porta G, Spirito A, et al. Suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in the treatment of resistant depression in adolescents: findings from the TORDIA study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(8):772–781. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilkinson P, Kelvin R, Roberts C, et al. Clinical and psychosocial predictors of suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in the Adolescent Depression Antidepressants and Psychotherapy Trial (ADAPT) Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(5):495–501. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10050718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dulit RA, Ryer MR, Leon AC, et al. Clinical correlates of self-mutilation in borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(9):1305–1311. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.9.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Favazza AR, Conterio K. Female habitual self-mutilators. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1989;79(3):283–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1989.tb10259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guan K, Fox KR, Prinstein MJ. Nonsuicidal self-injury as a time-invariant predictor of adolescent suicide ideation and attempts in a diverse community sample. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(5):842–849. doi: 10.1037/a0029429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Leo D, Burgis S, Bertolote JM, et al. Definitions of suicidal behavior: lessons learned from the WHO/EURO Multicentre Study. Crisis. 2006;27(1):4–15. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.27.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Carroll PW, Berman AL, Maris R, et al. Beyond the tower of Babel: a nomenclature for suicidology. In: Kosky RJ, Eshkevari HS, Goldney RD, et al., editors. Suicide prevention: the global context. New York (NY): Plenum Press; 1998. pp. 23–39. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Silverman MM, Berman AL, Sanddal ND, et al. Rebuilding the tower of Babel: a revised nomenclature for the study of suicide and suicidal behaviors: Part II: suicide-related ideations, communications and behaviors. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2007;37(3):264–277. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.3.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown MZ, Comtois KA, Linehan MM. Reasons for suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in women with borderline personality disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111(1):198–202. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.111.1.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muehlenkamp JJ. Self-injurious behavior as a separate clinical syndrome. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2005;75(2):324–333. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.75.2.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walsh BW. Treating self-injury: a practical guide. New York (NY): Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nock MK. Why do people hurt themselves? New insights into the nature and functions of self-injury. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2009;18(2):78–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01613.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Plener PL, Libal G, Nixon MK. Use of medication in the treatment of nonsuicidal self-injury in youth. In: Nixon MK, Heath NL, editors. Self-injury in youth: the essential guide to assessment and intervention. New York (NY): Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2009. pp. 275–308. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sandman CA. Psychopharmacologic treatment of nonsuicidal self-injury. In: Nock MK, editor. Understanding nonsuicidal self-injury: origins, assessment, and treatment. Washington (DC): American Psychological Association; 2009. pp. 291–322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brausch AM, Girresch SK. A review of empirical treatment studies for adolescents non suicidal self-injury. J Cogn Psychother. 2012;26(1):3–18. doi: 10.1891/0889-8391.26.1.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gonzales AH, Bergstrom L. Adolescent non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) interventions. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 2013;26(2):124–130. doi: 10.1111/jcap.12035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kerr PL, Muehlenkamp JJ, Turner JM. Nonsuicidal self-injury: a review of current research for family medicine and primary care physicians. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23(2):240–259. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2010.02.090110. Also available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20207935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suyemoto KL. The functions of self-mutilation. Clin Psychol Rev. 1998;18(5):531–554. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(97)00105-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arensman E, Townsend E, Hawton K, et al. Psychosocial and pharmacological treatment of patients following deliberate self-harm: the methodological issues involved in evaluating effectiveness. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2001;31(2):169–180. doi: 10.1521/suli.31.2.169.21516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brent DA, McMakin DL, Kennard BD, et al. Protecting adolescents from self-harm: a critical review of intervention studies. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52(12):1260–1271. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Levy KN, Yeomans FE, Diamond D. Psychodynamic treatments of self-injury. J Clin Psychol. 2007;63(11):1105–1120. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lieb K, Zanarini MC, Schmahl C, et al. Borderline personality disorder. Lancet. 2004;364(9432):453–461. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16770-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.MacPherson HA, Cheavens JS, Fristad MA. Dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents: theory, treatment adaptations, and empirical outcomes. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2013;16(1):59–80. doi: 10.1007/s10567-012-0126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nock MK, Teper R, Hollander M. Psychological treatment of self-injuring among adolescents. J Clin Psychol. 2007;63(11):1081–1089. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ougrin D, Latif S. Specific psychological treatment versus treatment as usual in adolescents with self-harm: systematic review and meta-analysis. Crisis. 2011;32(2):74–80. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ougrin D, Tranah T, Leigh E, et al. Practitioner review: self-harm in adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2012;53(4):337–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Townsend E, Hawton K, Altman DG, et al. The efficacy of problem-solving treatments after deliberate self-harm: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials with respect to depression, hopelessness and improvement in problems. Psychol Med. 2001;31(6):979–988. doi: 10.1017/S0033291701004238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wilkinson B. Current trends in remediating adolescent self-injury: an integrative review. J Sch Nurs. 2011;27(2):120–128. doi: 10.1177/1059840510388570. Also available from: http://jsn.sagepub.com/content/27/2/120.abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Linehan MM, Dimeff L, Koerner K, et al., compilers. In: Research on dialectical behavior therapy: summary of the data to date [Internet] Seattle (WA): The Linehan Institute, Behavioral Tech; 2014. [cited 2014 May 1]. Available from: http://behavioraltech.org/downloads/Research-on-DBT_Summary-of-Data-to-Date.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Coccaro EF, Harvey PD, Kupsaw-Lawrence E, et al. Development of neuropharmacologically based behavioral assessments of impulsive aggressive behavior. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1991;3(2):S44–S51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.US Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to clinical preventive services. Washington (DC): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Linehan MM. Skills training manual for treating borderline personality disorder. New York (NY): Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Linehan MM. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York (NY): Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Koons CR, Robins CJ, Tweed JL, et al. Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy in women veterans with borderline personality disorder. Behav Ther. 2001;32(2):371–390. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(01)80009-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Linehan MM, Armstrong HE, Suarez A, et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48(12):1060–1064. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810360024003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Linehan MM, Schmidt HIII, Dimeff LA, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy for patients with borderline personality disorder and drug-dependence. Am J Addict. 1999;8(4):279–292. doi: 10.1080/105504999305686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Linehan MM, Dimeff LA, Reynolds SK, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy versus comprehensive validation therapy plus 12-step for the treatment of opioid dependent women meeting criteria for borderline personality disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;67(1):13–26. doi: 10.1016/S0376-8716(02)00011-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Federici A, Wisniewski L. An intensive DBT program for patients with multidiagnostic eating disorder presentations: a case series analysis. Int J Eat Disord. 2013;46(4):322–331. doi: 10.1002/eat.22112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Geddes K, Dziurawiec S, Lee CW. Dialectical behaviour therapy for the treatment of emotion dysregulation and trauma symptoms in self-injurious and suicidal adolescent females: a pilot programme within a community-based child and adolescent mental health service. Psychiatry J. 2013;2013:145219. doi: 10.1155/2013/145219. Epub 2013 Jun 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Goldstein TR, Axelson DA, Birmaher B, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents with bipolar disorder: a 1-year open trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(7):820–830. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31805c1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McDonell MG, Tarantino J, Dubose AP, et al. A pilot evaluation of dialectical behavioural therapy in adolescent long-term inpatient care. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2010;15(4):193–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2010.00569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stanley B, Brodsky B, Nelson JD, et al. Brief dialectical behavior therapy (DBT-B) for suicidal behavior and non-suicidal self injury. Arch Suicide Res. 2007;11(4):337–341. doi: 10.1080/13811110701542069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Van Goethem A, Mulders D, Muris M, et al. Reduction of self-injury and improvement of coping behaviour during dialectal behaviour therapy (DBT) of patients with borderline personality disorder. Rev Int Psicol Ter Psicol = International Journal of Psychology & Psychological Therapy. 2012;12(1):21–34. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Murray AM, et al. Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(7):757–766. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McMain SF, Links PS, Gnam WH, et al. A randomized trial of dialectical behavior therapy versus general psychiatric management for borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(12):1365–1374. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09010039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pistorello J, Fruzzetti AE, MacLane C, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) applied to college students: a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(6):982–994. doi: 10.1037/a0029096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Verheul R, van den Bosch LMC, Koeter MWJ, et al. Dialectical behaviour therapy for women with borderline personality disorder: 12-month, randomised clinical trial in the Netherlands. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182(2):135–140. doi: 10.1192/bjp.182.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gratz KL, Gunderson JG. Preliminary data on acceptance-based emotion regulation group intervention for deliberate self-harm among women with borderline personality disorder. Behav Ther. 2006;37(1):25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gratz KL, Levy R, Tull MT. Emotion regulation as a mechanism of change in an acceptance-based emotion regulation group therapy for deliberate self-harm among women with borderline personality pathology. J Cogn Psychother. 2012;26(4):365–380. Also available from: http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/springer/jcogp/2012/00000026/00000004/art00007?crawler=true. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gratz KL, Tull MT. Extending research on the utility of an adjunctive emotion regulation group therapy for deliberate self-harm among women with borderline personality pathology. Personal Disord. 2011;2(4):316–326. doi: 10.1037/a0022144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Evans K, Tyrer P, Catalan J, et al. Manual-assisted cognitive-behaviour therapy (MACT): a randomized controlled trial of a brief intervention with bibliotherapy in the treatment of recurrent deliberate self-harm. Psychol Med. 1999;29(1):19–25. doi: 10.1017/S003329179800765X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tyrer P, Thompson S, Schmidt U, et al. Randomized controlled trial of brief cognitive behaviour therapy versus treatment as usual in recurrent deliberate self-harm: the POPMACT study. Psychol Med. 2003;33(6):969–976. doi: 10.1017/S0033291703008171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Weinberg I, Gunderson JG, Hennen J, et al. Manual assisted cognitive treatment for deliberate self-harm in borderline personality disorder patients. J Personal Disord. 2006;20(5):482–492. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2006.20.5.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Newham P. The singing cure: an introduction to voice movement therapy. Boston (MA): Shambhala Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Martin S, Martin G, Lequertier B, et al. Voice movement therapy: evaluation of a group-based expressive arts therapy for nonsuicidal self-injury in young adults. Music Med. 2013;5(1):31–38. doi: 10.1177/1943862112467649. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Woody GE, McLellan AT, Luborsky L, et al. Sociopathy and psychotherapy outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985;42(11):1081–1086. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790340059009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gregory RJ, Remen AL, Soderberg M, et al. A controlled trial of psychodynamic psychotherapy for co-occurring borderline personality disorder and alcohol use disorder: six-month outcome. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 2009;57(1):199–205. doi: 10.1177/00030651090570011006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Clarkin JF, Yeomans FE, Kernberg OF, Yeomans FE, editors. Psychotherapy for borderline personality: focusing on object relations. Arlington (VA): American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Clarkin JF, Foelsch PA, Levy KN, et al. The development of a psychodynamic treatment for patients with borderline personality disorder: a preliminary study of behavioral change. J Personal Disord. 2001;15(6):487–495. doi: 10.1521/pedi.15.6.487.19190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Clarkin JF, Levy KN, Lenzenweger MF, et al. Evaluating three treatments for borderline personality disorder: a multiwave study. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):922–928. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.164.6.922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Giesen-Bloo J, van Dyck R, Spinhoven P, et al. Outpatient psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: randomized trial of schema-focused therapy vs transference-focused psychotherapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(6):649–658. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.6.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nickel MK, Muehlbacher M, Nickel C, et al. Aripiprazole in the treatment of patients with borderline personality disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(5):833–838. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.5.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nickel MK, Loew TH, Gil FP. Aripiprazole in treatment of borderline patients, part II: an 18-month follow-up. Psychopharmacology. 2007;191(4):1023–1026. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0740-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Libal G, Plener PL, Ludolph AG, et al. Ziprasidone as a weight-neutral alternative in the treatment of self-injurious behavior in adolescent females. Child Adolescent Psychopharmacol News. 2005;10(4):1–6. Also available from: http://guilfordjournals.com/doi/abs/10.1521/capn.2005.10.4.1. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sonne S, Rubey R, Brady K, et al. Naltrexone treatment of self-injurious thoughts and behaviors. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1996;184(3):192–195. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199603000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Markovitz PJ, Calabrese JR, Schulz SC, et al. Fluoxetine in the treatment of borderline and schizotypal personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(8):1064–1067. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.8.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Markovitz PJ, Wagner SC. Venlafaxine in the treatment of borderline personality disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1995;31(4):773–777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Norelli LJ, Smith HS, Sher L, et al. Buprenorphine in the treatment of non-suicidal self-injury: a case series and discussion of the literature. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2013;25(3):323–330. doi: 10.1515/ijamh-2013-0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Roth AS, Ostroff RB, Hoffman RE. Naltrexone as a treatment for repetitive self-injurious behavior: an open-label trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57(6):233–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Brent DA, Emslie GJ, Clarke GN, et al. Predictors of spontaneous and systematically assessed suicidal adverse events in the Treatment of SSRI-Resistant Depression in Adolescents (TORDIA) study. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(4):418–426. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08070976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Goodyer I, Dubicka B, Wilkinson P, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and routine specialist care with and without cognitive behaviour therapy in adolescents with major depression: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2007;335(7611):142. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39224.494340.55. Also available from: http://www.bmj.com/content/335/7611/142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Linehan MM, McDavid JD, Brown MZ, et al. Olanzapine plus dialectical behavior therapy for women with high irritability who meet criteria for borderline personality disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(6):999–1005. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v69n0617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gratz KL, Lacroce DM, Gunderson JG. Measuring changes in symptoms relevant to borderline personality disorder following short-term treatment across partial hospital and intensive outpatient levels of care. J Psychiatr Pract. 2006;12(3):153–159. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200605000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hulbert C, Thomas R. Public sector group treatment for severe personality disorder: a 12-month follow-up study. Australas Psychiatry. 2007;15(3):226–231. doi: 10.1080/10398560701317101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hassanian-Moghaddam H, Sarjami S, Kolahi A-A, et al. Postcards in Persia: randomised controlled trial to reduce suicidal behaviours 12 months after hospital-treated self-poisoning. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;198(4):309–316. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.067199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hayakawa M. How repeated 15-minute assertiveness training sessions reduce wrist cutting in patients with borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychother. 2009;63(1):41–51. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2009.63.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nixon MK, Cheng M, Cloutier P. An open trial of auricular acupuncture for the treatment of repetitive self-injury in depressed adolescents. Can Child Adolesc Psychiatry Rev. 2003;12(1):10–12. Also available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2538454&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bedics JD, Atkins DC, Comtois KA, et al. Treatment differences in the therapeutic relationship and introject during a 2-year randomized controlled trial of dialectical behavior therapy versus nonbehavioral psychotherapy experts for borderline personality disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(1):66–77. doi: 10.1037/a0026113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chapman AL, Gratz KL, Brown MZ. Solving the puzzle of deliberate self-harm: the experiential avoidance model. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44(3):371–394. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Neacsiu AD, Rizvi SL, Linehan MM. Dialectical behavior therapy skills use as a mediator and outcome of treatment for borderline personality disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48(9):832–839. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ougrin D, Zundel T, Kyriakopoulos M, et al. Adolescents with suicidal and nonsuicidal self-harm: clinical characteristics and response to therapeutic assessment. Psychol Assess. 2012;24(1):11–20. doi: 10.1037/a0025043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Katz LY, Fotti S. The role of behavioral analysis in the pharmacotherapy of emotionally dysregulated problem behaviors. Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol News. 2005;10(6):1–5. Also available from: http://guilfordjournals.com/doi/abs/10.1521/capn.2005.10.6.1. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Olfson M, Gameroff MJ, Marcus SC, et al. Emergency treatment of young people following deliberate self-harm. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(10):1122–1128. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Robins CJ, Chapman AL. Dialectical behavior therapy: current status, recent developments, and future directions. J Personal Disord. 2004;18(1):73–89. doi: 10.1521/pedi.18.1.73.32771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA Group Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(6):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.