Abstract

A large theoretical and empirical literature documents the central role of familismo (i.e., a strong emphasis on family) in the functioning of Latino youth. Few studies, however, have examined its association with early childhood functioning. The present study explored the potential risk and protective effects of maternal familismo on the adaptive and mental health functioning of 4 - 5 year old Latino children. A sample of 205 Mexican and 147 Dominican immigrant families was recruited from New York City. Mothers reported on their level of familismo, and acculturative status. Mothers and teachers rated child adaptive behavior and internalizing and externalizing problems. Findings suggest that maternal familismo is not uniformly associated with positive or negative early developmental outcomes but that its effects are moderated by child gender, family poverty and cultural (e.g., maternal ethnic and US American identity) characteristics. In addition, different mechanisms were identified for each ethnic group. Familismo was associated both positively (for boys) and negatively (for poor children) with adaptive behavior in the Mexican American sample. In the Dominican American sample, familismo showed a wide range of positive, albeit moderated, effects. Prevention efforts that help parents critically evaluate the impact of familismo on family processes, and preserve those manifestations of familismo that are protective, may best promote Latino child well-being.

Keywords: familismo, early childhood, adaptive behavior, mental health functioning

As a traditional, collectivistic cultural group, the Latino population is believed to adhere deeply to the value of familismo (Arditti, 2006), which refers to mutual support and obligation between family members (Baca-Zinn & Wells, 2000; Calzada, Tamis-LeMonda, & Yoshikawa, 2012; Harrison, Wilson, Pine, Chan, & Buriel, 1990; Keefe, 1984). One definition (of several offered in the literature) suggests that familismo is comprised of four core tenets: a) belief that family comes before the individual; b) familial interconnectedness; c) belief in family reciprocity; and d) belief in familial honor (Lugo Steidel, & Contreras, 2003), and its behavioral manifestations include financial support, shared living, shared daily activities, childrearing, and support for immigration (Calzada et al., 2012). With its reliance on the family unit for instrumental and emotional support and family as referent, familismo has been shown to impact child development across several domains of well-being. Still, little is known about the association between familismo and child functioning during early childhood, a period during which key developmental competencies take shape. The present study examined maternal familismo in relation to children's functioning in a sample of Latino immigrant families of 4- and 5-year old children.

Familismo and Child Developmental Competencies

Traditionally, research on familismo with Latino immigrant youth has examined its protective effects because of the multiple benefits typically associated with the availability of a large family unit comprising nuclear and extended family members. For example, familismo may enhance the development of adaptive behavior among Latino children via modeling as their parents attend to the instrumental and emotional needs of extended family members. In addition, Latino children raised in highly familistic homes may be more likely to have responsibilities that benefit the family unit, such as assisting with childcare of younger family members (Calderon, Knight, & Carlo, 2011). As children are taught to put family needs before their own, they may be more likely to develop sensitivity for others’ needs.

Similarly, there is some evidence that familismo may be protective in the development of school functioning. In homes where familismo is valued, youth have higher class attendance and apply greater academic effort as they are motivated to do well in school for the sake of the family (Esparza & Sánchez, 2008; LaRoche & Shriberg, 2004). Parental monitoring and parent involvement in education associated with familismo have been found to promote academic achievement (Loukas & Prelow, 2004; Niemeyer, Wong, & Westerhaus, 2009), and the social capital afforded by family networks has been linked to higher academic performance (Esparza & Sanchez, 2008) and more informed educational decisions (Valdez & Rodriguez, 2002). At the same time, however, family obligations may interfere with academic success as they put a toll on children's time and energy that can lead to school absences, school dropout and lower rates of college enrollment (Desmond & Lopez-Turley, 2009; LaRoche & Shriberg, 2004; Suarez-Orozoco & Suarez-Orozoco, 2001; Velez, 1989). Based on a study with a national sample of immigrant high school students, Portes (1999) concluded that it is “moderate attachment to one's family” (p. 502, emphasis added) that promotes academic achievement.

Other studies corroborate the potential risk caused by very high levels of familismo for youth mental health (Fuligni, Tseng, & Lam, 1999; Marsiglia, Kulis, Parsai, Villar, & Garcia, 2009). Most notably, Zayas and colleagues showed that suicidal Latina adolescents explained their suicidal ideation in terms of sacrificing for their families (Nolle, Gulbas, Kuhlberg, & Zayas, 2012). Yet others find that the family routines and cohesion that characterize familismo protect adolescent girls against internalizing problems (Loukas & Prelow, 2004; O'Donnell, O'Donnell, Wardlaw, & Stueve, 2004), and that family conflict and a lack of family support (i.e., a lack of familismo) place youth at risk for internalizing problems (Coatsworth et al., 2000).

Familismo is expected to reduce risk for externalizing behaviors, including substance use, by ensuring a strong attachment to family and fostering conventional ties that dictate higher levels of parental monitoring and give parents more influence over their adolescent's behavior in ways that discourage Latino youth from engaging in a variety of problem behaviors (Brooks, Stuewig, & LeCroy, 1998; Keefe, Padilla, & Carlos, 1978; Loukas & Prelow, 2004). Recent evidence further suggests that familismo may be protective against externalizing problems via its association with the use of positive parenting practices (Calzada, Huang, & Brotman, 2012; Santisteban, Coatsworth, Briones, Kurtines, & Szapocznik, 2012). But while some studies suggest that familismo is indeed protective against substance use (Gil, Wagner, & Vega, 2000; Horton & Gil, 2008) and behavior problems (Gamble & Modry-Mandell, 2008; German, Gonzales, & Dumka, 2009; Marsiglia, Parsai, & Kulis, 2009), including violent behavior (Estrada-Martinez, Padilla, Caldwell, & Schultz, 2011), others find no significant association (Pabon, 1998; Shih, Miles, Tucker, Zhou, & D'Amico, 2010, 2012; Venegas, Cooper, Naylor, Hanson, & Blow, 2012). A study with Mexican American youth found that high familismo may even increase adolescent girls’ risk for externalizing problems when manifested in the context of perceived discrimination (Delgado, Updegraff, Roosa, & Umaña-Taylor, 2011).

Evidence for Moderation

In light of the inconsistencies in the literature, Calzada, Tamis-LeMonda and Yoshikawa (2012) posit that familismo manifests along a continuum in which costs and benefits coexist and may confer risk or protection depending on the ecological and developmental context of the child. For example, familismo may be protective for children of mothers who are employed outside the home because it ensures the availability of additional caregivers, but it may have no effect on children whose mothers are not employed. In representing a set of interrelated risk and protective factors, familismo may also exert unique effects on different domains of Latino youth functioning. Children of employed mothers may be protected against externalizing problems as their adult family members closely monitor their behavior, but for these same children, familismo may have no impact on internalizing functioning. Evidence for moderation by demographic characteristics comes from a study of island and mainland Puerto Rican youth which found that familismo was protective against antisocial behavior for girls regardless of age (i.e., 5 – 13 years), but for boys only when they were younger (i.e., 5 – 9 years old; Morcillo et al., 2011).

A growing literature also shows how cultural context interacts with familismo to influence child functioning. For example, parent-adolescent conflict is more predictive of internalizing problems for adolescents with higher Latino cultural involvement, presumably because the dictates of familismo exacerbate the effects of conflict within the family (Smokowski & Bacallao, 2007). For adolescents with higher involvement in US American culture, and for bicultural adolescents, risk for internalizing and externalizing symptoms may be lower (Loukas & Prelow, 2004; Gonzales et al, 2008; Schwartz, Zamboanga, & Jarvis, 2007; Smokowski & Bacallao, 2007). In addition, aspects of the home environment (e.g., parenting practices; Peña et al., 2011) and family relations (e.g., mother-daughter mutuality; Baumann, Kuhlberg, & Zayas, 2010) have been found to moderate associations between familismo and suicidality.

The Present Study

The present study builds on the extant literature to examine the association between maternal familismo and the functioning of 4- and 5-year old Latino children. Almost all past studies of familismo have been conducted with older youth; virtually nothing is known about maternal familismo and early child development. From a theoretical perspective, early childhood marks a critical juncture in development as early ecological factors tend to activate a cascade toward later developmental outcomes (Dodge, Malone, Lansford, Miller, Pettit, & Bates, 2009), making its study ideal for the identification of risk and protective factors that are expected to have long-term impact. We examined early childhood outcomes in three domains: adaptive behavior, externalizing problems and internalizing problems, and in two settings: home and school. We considered adaptive behavior as the primary outcome because we expect that in young children, the influence of familismo on adaptive skills may be more immediate whereas its influence on mental health may emerge over time, as problems crystalize (or are curtailed).

Consistent with the goal of examining both risk and protection, we conduct a more nuanced examination of familismo by considering contextual characteristics that may moderate its association with Latino child functioning. We consider child gender and acculturative status, given past evidence (albeit with older children) of moderation (i.e., Morcillo et al., 2011; Smokowski & Bacallao, 2007), and poverty given theoretical arguments regarding its potentially moderating role (Calzada et al., 2012b). For the sake of parsimony, we limit moderation analyses to these three variables, recognizing the overlap with other potentially relevant factors (e.g., poverty status is highly correlated with mother's employment and marital status and so the latter two were not included).

Importantly, we studied two specific ethnic groups because according to the integrative developmental theory, ethnicity, as a social position variable, is associated with a host of social mechanisms that ultimately influence developmental outcomes (Garcia-Coll et al., 1996). Consistent with this view, Calzada et al. (2012b) have argued that the manifestation of familismo, and its influence on developmental trajectories, are context-dependent, a context defined in large part by a child's ethnicity. Neither of these conceptual models, however, addresses the question of how precisely to define ethnicity (i.e., as Latino--a pan-ethnic categorization, or as Mexican orDominican American--a specific ethnic group categorization). In choosing to operationalize ethnicity with more specificity (i.e., based on country of origin), we are in essence, making it an independent variable in our study. Concerns over using race or ethnicity as an independent variable have been expressed by scholars (Helms et al., 2005) based on the premise that race/ethnicity is simply a proxy for underlying concepts and as such, a meaningless variable for psychological research. In the present study, we too view ethnicity as a proxy, but recognize that the underlying factors and processes are not yet identified or understood by scholars, or were simply not measured in our study. In the absence of these data, we rely on ethnic categorizations.

We consider additional advantages of our approach to defining ethnicity with more precision. When ethnicity is operationalized by collapsing individuals from various Spanish-speaking countries into one category, within-group differences along historical, social and cultural dimensions are likely obfuscated, making it difficult to interpret study findings (Szapocznik, Prado, Burlew, William, & Santisteban, 2007). Alternately, our categorization based on country of origin recognizes that in certain but unknown ways, a child's ethnic group membership influences his or her development. Finally, sampling based on country of origin is consistent with the goal of exploring developmental mechanisms within specific ethnic groups, rather than examining generalization of such mechanisms across groups, and thus was the approach used in the present study.

The first group we selected was Mexican Americans (MA) because the majority of US Latinos (65%) come from Mexico, and though they have not historically resided in the Northeast, MAs are poised to become the largest group in New York City (NYC; where the present study took place) by 2021. The second group was Dominican Americans (DA), who are expected to surpass Puerto Ricans to become the largest group, after Mexicans, in New York City (Bergad, 2011). Significant gaps exist in the study of MA and DA families to date. DAs have been neglected in the literature, such that virtually nothing is known about family processes and child development in this group although they have had a long-standing presence (i.e., more than 50 years) in the northeastern US. MAs have been the focus of a relatively large and growing literature, but consistent with past population trends, studies have been primarily limited to samples from traditional receiving communities in the Western US. Migration to other states, such as New York, is shifting the demographic profile of the MA population, providing opportunities to examine the generalizability of past study findings to MA families residing in new receiving communities.

Methods

Participants

Participants were drawn from a prospective longitudinal study examining the early childhood development of Mexican (MA) and Dominican American (DA) children. In the larger, ongoing study, children who were enrolled in the first two years of recruitment (2010 and 2011; N=412), who had complete data (n=383; 93%) and who had immigrant mothers (n=352; 92%) were included in the present study sample. Despite our interest in MA and DA mothers across generations, we excluded the 31 children of US-born mothers because we did not have the power to analyze whether there were meaningful differences on study variables based on mother's nativity. Mother-child dyads were recruited from pre-kindergarten and kindergarten classrooms from 24 public schools in NYC. All children were 4 or 5 years old at the time of enrollment. As shown in Table 1, MA (n=205) and DA (n=147) families differed on most demographic characteristics, reflecting the unique ecology of each group. For example, compared to DA mothers, MA mothers were more likely to be married to or living with the child's father and to have larger families. MA mothers were also younger, less likely to have graduated from high school, less likely to be working for pay. The average income was $19,685 (SD=12,876) for MA families and $24,250 (SD=21,101) for DA families. In both groups, household income had a wide range (up to $93,000 in the MA sample; up to $150,000 in the DA sample), but only 7% of MA mothers, and 12% of DA mothers, reported an income above $40,000. In considering poverty status, MA mothers and their children were more likely than DAs to be classified as poor.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics for Mexican American and Dominican American Families

| MA (n=205) | DA (n=147) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t | p | |

| Child Age | 4.68 | .59 | 4.68 | .54 | .05 | .96 |

| Maternal Age | 31.34 | 5.79 | 34.04 | 7.45 | −3.81 | <.001 |

| Household size | 5.59 | 1.81 | 4.46 | 1.37 | 6.35 | <.001 |

| % | % | χ 2 | p | |||

| Child gender: male | 49.27 | 48.30 | 0.03 | .86 | ||

| Child foreign-born | 3.52 | 17.81 | 19.88 | <.001 | ||

| Two-parent home | 88.29 | 62.59 | 32.51 | <.001 | ||

| Mother <high school education | 61.95 | 18.37 | 66.08 | <.001 | ||

| Mother works for pay | 24.39 | 62.59 | 51.89 | <.001 | ||

| Family lives in poverty | 83.90 | 60.54 | 24.37 | <.001 | ||

Note. MA = Mexican American; DA = Dominican American. Family poverty status based on federal guidelines, with consideration for number of persons living in the home.

Measures

Demographic Characteristics

Mothers completed an extensive demographic form that included information on date of birth (mother and child), immigrant status, years of residence in the US, employment status, marital status, household income (brought in by any person within the home who shared household expenses with the mother), and household composition. To calculate poverty, we considered income relative to number of persons living in the home for whom the mother was financially responsible or with whom she was sharing household expenses. We used the federal poverty guidelines, which considers number of persons in the home, to categorize families as poor, defined as living 100% below the poverty line.

Maternal Acculturative Status

The Abbreviated Multidimensional Acculturation Scale AMAS; Zea, Asner-Self, Birman, & Buki, 2003) is a 42-item measure of acculturative status that was developed with Spanish- and English-speaking Latinos. Items are rated on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree) and correspond to specific domains of cultural competence, language competence and identity; higher scores indicate higher levels of competence or identity. All domains are measured for both culture of origin (enculturation) and mainstream/ “US American” culture (acculturation), allowing for an examination of acculturation/enculturation as a bi-dimensional construct. The AMAS subscales showed adequate internal consistencies with the present sample of MA and DA Spanish- and English-speaking mothers (alphas ranged from .77-.93).

Familismo

The Mexican American Cultural Values Scales (MACVS; Knight et al., 2010) assesses several Mexican cultural values including familismo. The familismo scale has 16 items rated from 1 (not at all) to 5 (completely) that tap into the desirability to maintain close relationships (“emotional support”), the importance of tangible caregiving (“obligation to family”), and the reliance on communal interpersonal reflection to define the self (“family as referent”). Though the MACVS was developed for MA families, familismo is a relevant construct for all Latinos including DA families (Calzada, Tamis-LeMonda, & Yoshikawa, 2012); confirmatory factor analyses showed reasonable model fit indices for both MA and DA mothers (RMSEA=.06 for both samples). The MACVS was developed in Spanish and English (Knight et al., 2010) and showed high internal consistency (.83-.98) in both languages, and with both ethnic groups, in the present study.

Child Functioning

The Behavior Assessment System for Children, Parent Rating Scale and Teacher Rating Scale (BASC PRS, BASC TRS, Kamphaus, Reynolds, & Hatcher, 1999) is a measure of child functioning for children between the ages of 2 and 18 years. Composite scales include Adaptive Behavior, Externalizing Problems and Internalizing Problems. The Adaptive Behavior composite includes scales of social skills and adaptability, the Externalizing Problems composite scale includes subscales of aggression and conduct problems, and the Internalizing Problems composite scale includes subscales of depression, anxiety and somatization. The BASC-P was standardized with a small sample of Spanish-speaking Latino families and showed adequate psychometric properties (Kamphaus, Reynolds, & Hatcher, 1999). In the present study sample, internal consistencies for MA and DA children ranged from .81-.87 for parent report, and .90-.95 for teacher report.

Procedure

Families were recruited for a longitudinal study of Latino child development from pre-kindergarten and kindergarten classrooms in 24 partner public schools. Specifically, MA families were recruited from 13 elementary schools, and DA families from 11 different elementary schools in the city. Consistent with the aims of the larger study, three inclusion criteria were applied, and children of mothers who self-identified as MA or DA, who were newly enrolled in the school, and who had no documented developmental disorder were invited to participate in the project. At each school, bilingual research staff attended parent meetings and were present during daily school drop-off and pick-up to inform mothers of the study. The recruitment rate averaged 74% (53 – 94%) across the 24 schools; 16% of families identified as eligible could not be contacted during recruitment efforts and 10% refused to participate. Interested mothers were scheduled for an appointment at their child's school where they were met by research staff for an interview. Mothers were asked to indicate their language of preference for the study activities: the majority of mothers (99% of MA and 86% of DA) chose to be interviewed in Spanish. After obtaining consent, interview questions and response choices were provided to mothers in written form (via a response booklet) and were also read aloud by research staff; mothers’ oral responses were recorded. Upon completing the 90-minute interview, mothers were paid a small stipend for their participation. Teachers of participating children (99% of mothers consented to the collection of teacher report) were then asked to consent and complete a packet of questionnaires on child functioning. Teachers received a stipend for classroom supplies and hands-on support in the classroom as incentive for participating in the project. 144 teachers provided data for 95% (n=194) of MA and 92% (n=135) of DA participant children. There were no differences on demographic characteristics or on study variables between children who had teacher ratings and those who did not. All of the data used in the present study were collected at Time 1.

Approach to analyses

To study the association between maternal familismo and child functioning, we modeled child outcomes as a function of familismo. We conducted analyses separately for each child outcome, and separately for MA and DA families because, as described above, our primary interest was in examining child development within, not across, ethnic groups (i.e., ethnicity as a sampling strategy). In addition, this analytic approach is more appropriate when variances are not equivalent across groups, as was the case on several key variables (e.g., US American identity, ethnic identity, English and Spanish language competence, familismo) in the present study.

To examine whether associations between familismo and child functioning were moderated by select contextual characteristics, two models were tested—one examined demographic characteristics as moderators, and the other examined cultural characteristics as moderators. We included child gender and family poverty status as potential moderators representing family demographics. We included maternal ethnic identity, US American identity, and English and Spanish language competence as potential moderators representing familial cultural context. We focused on maternal (rather than child) acculturative status because of the young age of participating children and because of a growing literature documenting the importance of parental acculturative status for Latino child development (Calzada et al., 2012a; Gonzales, Knight, Morgan-Lopez, Sanz, & Sirolli., 2002). In this model, we did not control for demographic variables because none were significantly correlated with the familismo scale.

In each set of analyses, we included familismo, a set of moderators (demographic or cultural), and a set of interaction terms between familismo and each potential moderator. A significant interaction effect would indicate that the association between familismo and a child outcome is different based on the level/status of the moderator. For variables with significant interaction effects, post hoc regression analyses were carried out to further understand whether there was an association and if so, how strong, between familismo and the child outcome for each subgroup defined by the moderating variable. A limitation of the post hoc analyses is the limited power to detect subgroup differences given the relatively small n of each subgroup, thus we focused on the pattern of associations in these interactions as well. Our approach is modeled after developmental studies with similar aims (Huang, Caughy, Miller, & Genevro, 2005; Lee, Halpern, Hertz-Picciotto, Martin, & Suchindran, 2006). While all results are presented in the text, only significant interactions on adaptive behavior, our primary outcome, are plotted in figures.

For behavior at school, some teachers provided data on multiple students (the average number of students rated by each teacher was 2.33 (SD=1.48), with less than 1% of teachers rating > 5 students). To account for correlations between outcomes of children rated by the same teachers (Muthén & Satorra, 1995), we applied linear mixed effects models (using SAS PROC MIXED procedure) and included teacher as a random effect. Again, all analyses were conducted separately for each child outcome and for MA and DA families.

Results

Maternal Acculturative Status, Familismo and Child Functioning

Descriptive statistics for all study variables are presented in Table 2. In general, DA mothers were more acculturated (i.e., had higher US American identity and English language competence) than MA mothers, though neither group was highly acculturated. MA mothers reported a significantly higher ethnic identity than DA mothers, though ethnic identity was high for both groups. DA mothers reported higher Spanish language competence than MA mothers, perhaps because of the items related to literacy. All mothers reported high levels of familismo, but familismo was significantly higher among DA than among MA mothers. According to ratings from both mothers and teachers, DA children had higher levels of adaptive behavior (at home and school) than MA children. According to teacher ratings, DA children had higher levels of externalizing behavior problems in school relative to MA children.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and Correlations of study variables for Mexican American and Dominican American Families

| MA | DA | Correlations among Study Variables | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

| 1. Familismo | 4.26 (.52) | 4.49 (.39)‡ | - | .01 | .17* | −.20*. | .15 | .16* | .04 | .03 | −.05 | .11 | −.13 |

| 2. US American identity | 2.14 (.82) | 2.82 (.91)‡ | −.04 | - | −.07 | .23 | −.13 | .16* | .03 | −.02 | .10 | −.03 | .09 |

| 3. Ethnic identity | 3.93 (.24) | 3.86 (.36)† | .14* | −.15* | - | −.21* | .16 | −.18* | −.01 | .04 | .001 | −.05 | −.10 |

| 4. English competence | 1.80 (.53) | 2.39 (.84)‡ | −.11 | .13 | −.13 | - | −.05 | .12 | .09 | −.004 | −.04 | .14 | .16 |

| 5. Spanish competence | 3.62 (.53) | 3.74 (.41)† | .02 | −.17* | .01 | .17* | - | .12 | −.07 | −.08 | .06 | −.16* | −.06 |

| 6. Adaptive behavior (P) | 47.06 (9.12) | 52.56 (9.22)‡ | .10 | −.04 | −.01 | .09 | .17* | - | .27** | −.32** | −.17 | −.07 | −.19* |

| 7. Adaptive behavior (T) | 45.60 (8.83) | 48.20 (9.28)† | −.14 | .02 | −.01 | .16* | −.02 | .22** | - | −.27** | −.40*** | −.07 | −.27** |

| 8. Externalizing behavior (P) | 47.80 (8.98) | 47.95 (10.00) | −.004 | −.05 | .06 | .02 | .05 | −.32*** | −.03 | - | .37*** | .55*** | .21* |

| 9. Externalizing behavior (T) | 45.92 (7.57) | 47.89 (8.69)† | −.06 | −.05 | −.001 | −.10 | −.10 | −.07 | −.21** | .27*** | - | .004 | .47*** |

| 10. Internalizing behavior (P) | 53.44 (10.64) | 53.58 (10.32) | .02 | −.02 | −.04 | −.03 | .004 | −.18* | −.06 | .61*** | .05 | - | .20* |

| 11. Internalizing bahavior (T) | 45.80 (8.49) | 47.16 (8.92) | −.05 | −.01 | .06 | −.16* | −.07 | −.12 | −.25** | .14* | .28*** | .18* | - |

Note. MA = Mexican American; DA = Dominican American. Variables 1-5 are maternal cultural measures, and variables 6-11 are child outcome measures. P = Parent rating. T = Teacher rating. T-scores presented for parent and teacher ratings.

indicates a significant group difference with mean at the p level <.001.

indicates a significant group difference in mean at the p level <.05.

Correlations for the MA sample presented below the diagonal, and correlations for the DA sample presented above the diagonal

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001.

Main Effects of Familismo on Child Functioning

Model 1 examined the main effect of familismo on child functioning for MAs (Table 3) and DAs (Table 4). Familismo was related to higher levels of adaptive behavior in the MA and DA samples, and to lower levels of internalizing problems in the DA sample.

Table 3.

Main and Moderated Effects of Familismo on Mexican American Child Functioning

| Adaptive | Externalizing | Internalizing | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (P) | (T) | (P) | (T) | (P) | (T) | |||||||

| Estimate (SE) | p | Estimate (SE) | p | Estimate (SE) | p | Estimate (SE) | p | Estimate (SE) | p | Estimate (SE) | p | |

| Model 1 | ||||||||||||

| Familismo | 1.77 (1.22) | .15 | −2.32 (1.11) | .04 | −0.08 (1.20) | .95 | −0.66 (1.00) | .51 | 0.30 (1.43) | .83 | −0.02 (1.00) | .99 |

| Model 2 | ||||||||||||

| Male × Familismo | 0.95 (2.58) | .71 | 4.90 (2.34) | .04 | 4.30 (2.52) | .09 | 0.87 (2.13) | .68 | 3.70 (2.92) | .21 | −2.31 (2.13) | .28 |

| Poverty × Familismo | −3.94 (3.12) | .21 | −7.56 (2.90) | .01 | −3.14 (3.04) | .30 | 1.30 (2.60) | .62 | −1.91 (3.56) | .59 | 1.05 (2.64) | .69 |

| Model 3 | ||||||||||||

| Am Identity× Familismo | −2.67 (1.69) | .12 | 0.86 (1.52) | .57 | −1.20 (1.68) | .47 | 0.90 (1.40) | .52 | −0.98 (1.99) | .62 | 0.04 (1.38) | .98 |

| Eth Identity× Familismo | −7.90 (7.37) | .28 | −6.35 (6.69) | .34 | 4.48 (7.31) | .54 | 3.58 (6.05) | .55 | 1.90 (8.66) | .83 | 7.31 (6.08) | .23 |

| Eng Comp× Familismo | −2.08 (2.76) | .45 | −4.32 (2.52) | .09 | 0.30 (2.73) | .91 | 2.04 (2.32) | .38 | 2.98 (3.24) | .36 | 0.20 (2.30) | .93 |

Note. (P) = Parent rating; (T) = Teacher rating. Am=American; Eth=Ethnic. Eng Comp=English language competence. Gender and poverty status were dichotimized variables (coded as 0/1). All other continuous predictors were centered at the mean. Model 1 did not control for demographic factors, but similar results were found when including demographic factors as covariates. Model 2 also included main effects of poverty, child gender, and familismo (estimates not shown). Model 3 also included main effects of maternal US American identity, maternal ethnic identity, maternal English language competence, and familismo (estimates not shown).

Table 4.

Main and Moderated Effects of Familismo on Dominican American Child Functioning

| Adaptive | Externalizing | Internalizing | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (P) | (T) | (P) | (T) | (P) | (T) | |||||||

| Estimate (SE) | p | Estimate (SE) | p | Estimate (SE) | p | Estimate (SE) | p | Estimate (SE) | p | Estimate (SE) | p | |

| Model 1 | ||||||||||||

| Familismo | 3.90 (1.96) | .05 | 1.01 (2.02) | .62 | 0.64 (2.16) | .77 | −1.16 (1.97) | .56 | 2.83 (2.21) | .20 | −4.26 (1.94) | .03 |

| Model 2 | ||||||||||||

| Male × Familismo | 9.60 (3.93) | .02 | 3.27 (2.94) | .27 | −4.72 (4.51) | .30 | −2.48 (4.06) | .54 | −0.25 (4.52) | .96 | 3.70 (4.07) | .37 |

| Poverty × Familismo | 0.33 (4.48) | .94 | 1.50 (2.83) | .60 | 4.85 (4.33) | .27 | −1.32 (4.11) | .75 | 1.61 (4.70) | .73 | −8.59 (4.13) | .04 |

| Model 3 | ||||||||||||

| Am Identity× Familismo | −5.05 (2.11) | .02 | −3.27 (2.27) | .16 | 2.68 (2.44) | .28 | 5.11 (2.24) | .03 | 1.41 (2.42) | .56 | 3.83 (2.28) | .10 |

| Eth Identity× Familismo | 7.82 (5.49) | .16 | 4.96 (6.65) | .46 | 4.32 (6.36) | .50 | −5.13 (6.45) | .43 | 13.49 (6.29) | .03 | −0.24 (6.49) | .97 |

| Eng Comp× Familismo | 1.36 (2.17) | .53 | 1.96 (2.28) | .39 | 1.01 (2.51) | .69 | −0.61 (2.17) | .78 | 4.12 (2.48) | .10 | −0.51 (2.20) | .82 |

Note. (P) = Parent rating; (T) = Teacher rating. Am=American; Eth=Ethnic. Eng-Comp=English language Competence. Gender and poverty status were dichotimized variables (coded as 0/1). All other continuous predictors were centered at the mean. Model 1 did not control for demographic factors, but similar results were found when including demographic factors as covariates. Model 2 also included main effects of poverty, child gender, and familismo (estimates not shown). Model 3 also included main effects of maternal US American identity, maternal ethnic identity, maternal English language competence, and familismo (estimates not shown).

The Moderating Role of Demographic Characteristics

Model 2 tested moderation effects of demographic factors (Tables 3 and 4). For MA children, the association between familismo and teacher-rated adaptive behavior was moderated by family poverty status (p = .01) and child gender (p = .04). Post hoc analyses showed a clear pattern in which familismo was associated with lower adaptive behavior at school among poor families (β (SE) = -6.45 (2.37), p =.01), but not among non-poor families (β (SE) = 1.78 (2.55), p =.49; see Figure 1a). On the other hand, familismo was associated with higher adaptive behavior at school among boys (β (SE) = 6.61 (3.35), p =.05), but not girls (β (SE) = 1.79 (2.55), p =.49; see Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

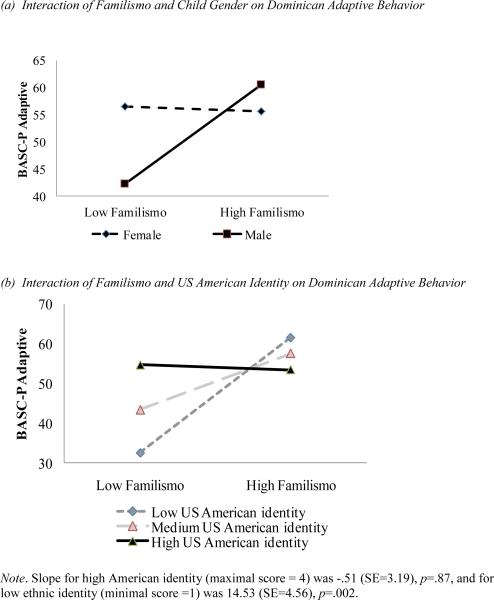

Among DA children, the association between familismo and adaptive behavior at home was moderated by gender (p = .02). As shown (Figure 2a), familismo was positively (albeit not significantly) associated with adaptive behavior at home among boys (β (SE) = 4.50 (3.59), p =.21), but not girls (β (SE) = -0.45 (3.17), p =.89). The association with teacher-rated internalizing problems was moderated by family poverty (p = .04). Specifically, familismo was related to lower internalizing problems among children from poor families (β (SE) = -8.37 (3.12), p =.01), but unrelated among children from non-poor families (β (SE) = .05 (3.65), p =.99).

Figure 2.

The Moderating Role of Cultural Characteristics

The final model (Model 3) tested for interactions between cultural characteristics (i.e., maternal acculturative status) and familismo (Tables 3 and 4). There were no significant moderation effects for MA children. Among DA children, both ethnic identity and US American identity emerged as significant moderators of child functioning Specifically, ethnic identity moderated the relation between familismo and parent-rated internalizing problems (p = .03). At lower levels of ethnic identity, but not at higher levels, familismo was associated with lower internalizing problems (β (SE) = -25.30 (12.61), p =.05). American identity moderated the association between familismo and both parent-rated adaptive behavior (p = .02) and teacher-rated externalizing problems (p = .03). At lower levels of US American identity, but not at higher levels, familismo was associated with better adaptive behavior (β (SE) = -0.51 (3.19), p =.87) (Figure 2b), and lower levels of externalizing problems (β (SE) = -11.11 (4.84), p =.03).

Discussion

Familismo has often been described in the literature as a protective factor that promotes well-being through its emphasis on family cohesion and support. The present study examined familismo from a more nuanced perspective considering risk and protective effects for child development among Mexican (MA) and Dominican American (DA) families of young children. Study findings, which support a framework that considers differential effects across developmental outcomes and moderating effects of background characteristics (Calzada et al., 2012b), suggest that during early childhood, maternal familismo has a somewhat robust protective effect, particularly in the domain of adaptive behavior, among DA children but not among MA children, for whom familismo in some cases was associated with risk.

Specifically, for MA children who were poor, familismo was significantly and negatively associated with adaptive behavior at school; no association was found among non-poor MA children. One possible explanation for this pattern is that in poor MA families, the behavioral manifestations of familismo are especially costly because of the limited resources available to the family unit. For example, as familismo manifests in shared and fluid living arrangements, extended family members may unexpectedly move in and out of the home (Calzada et al., 2012b), contributing to an less predictable home environment of temporary household residents who may be less likely to offer the consistent support that is often associated with (and a benefit of) family extendedness (Harrison et al., 1990). We did not assess the fluidity of household compositions, but past findings suggest that such patterns may be common in poor MA families (even relative to other poor Latino families) in NYC (Calzada, Tamis-LeMonda et al. 2012), and current findings suggest the possibility that stressors at the intersection of familismo and poverty may undermine the development of adaptive behaviors in MA children.

On the other hand, familismo was protective for MA (and DA) boys in the domain of adaptive behavior. To our knowledge, only one other study of Latino children has examined moderation by gender, and those findings showed that boys benefitted from familismo only at early ages (from 5- 9 years), while girls benefited throughout childhood (from 5 - 13 years). The authors speculate that the greater parental monitoring associated with familismo and directed more to girls than boys as children get older protects them from engaging in risky behavior. At the same time, the greater caretaking responsibilities given to Latina girls during adolescence compared to their male peers puts them at risk for poor academic outcomes because their familial obligations interfere with schooling (Valenzuela, 1999). It seems, then, that the behavioral manifestations of familismo unfold according to prescribed gender-specific roles, making adherence to familismo more costly for girls than for boys, with both positive and negative effects. Moreover, these gender-specific effects appear to be moderated by the developmental stage of the child. Future studies using longitudinal data are needed to better understand the nature of these potential three-way interactions.

Among DA children, familismo appeared to have several protective functions, particularly for children whose mothers had a low sense of ethnic or US American identity. Specifically, high familismo was associated with more adaptive behavior and fewer internalizing problems in the home, and fewer externalizing problems at school, when mothers had a low identity. Conversely, low familismo in concert with low maternal ethnic/US American identity was associated with poorer psychological functioning of children. Past studies suggest that both national and ethnic identity, but especially the latter, are associated with self-esteem and well-being (Phinney, Horenczyk, Liebkind, & Vedder, 2001), and low levels may be a marker for maternal stress, depressive symptoms and social isolation. For at-risk mothers, familismo may provide a vital social network of family members that helps foster healthy maternal functioning and in turn benefits their young children.

In general, the present study findings suggest that although familismo is highly valued in both MA and DA families (as indicated by high mean levels of endorsement), it may play a greater role, and have a more protective effect, in the development of young DA children. Its effects on MA child development appear more limited, serving as a protective factor for boys only and only in the domain of adaptive behavior. Moreover, familismo was found to confer risk for the adaptive behavior of poor MA children; given the high rates of poverty that characterize the MA child population in the US, this finding of a potential negative effect for an already vulnerable population requires further investigation.

It is noteworthy that the opposite pattern was seen with DA children, for whom familismo was protective against internalizing problems in the context of poverty. These inconsistent findings seem difficult to reconcile given assumptions regarding the universality of social processes, but a robust theoretical and empirical literature suggests that the impact of poverty on children depends on a number of contextual factors, in particular social support (see Bradley & Corwyn, 2002, for a review). We are presently collecting data on perceived social support among mothers with the aim of shedding light on these complex associations in MA and DA families. It is possible, for example, that as part of a new immigrant group to NYC, MA mothers had limited social support, whereas DA mothers, as part of a well-established immigrant group in the city, had adequate support. In the present samples, even as both groups were living in urban, disadvantaged communities, MA mothers were more likely to be foreign-born, linguistically isolated and less educated. In addition, though not assessed in the present study, the MA population in NYC is less likely to be documented and when documented, to be US citizens, compared with the DA population (Bergad, 2011), and undocumented status is associated with additional stressors, including more stressful work conditions and limited access to social benefits. Given these more pronounced risk factors, it may be that familismo was not sufficient to offset the higher level of disadvantage experienced by poor MA families relative to poor DA families (Sherraden & Barrera, 1997). For example, in the context of such high risk (e.g., from undocumented status), mothers may not have been able to engage in high levels of familistic behaviors in spite of their strong valuing of familismo.

The unique ecological circumstances of each group may also explain why familismo was generally not associated in any of the same ways with the functioning of DA relative to MA children. In NYC, MA families appear to live in larger households characterized by overcrowding and frequently changing household compositions (Calzada et al., 2012b). In this home environment, high familismo may create large extrafamilial networks with members that are not well acquainted and where obligation is expected but emotional connections and support are limited. At the neighborhood level, MA families in NYC are less likely to live in Mexican or even Latino communities, whereas DA families are largely concentrated in ethnic enclaves that may facilitate the cultivation of cultural values and behaviors (Yoshikawa, 2011). By living in more diverse neighborhoods, MA mothers may inevitably observe and draw on varied cultural notions of family so that even as they value familismo as conceptualized in Latino cultures, they embrace new behavioral expressions of family with differential impacts on children.

Unfortunately, the present study did not include a behavioral measure of familismo. But given the multidimensional nature of familismo (i.e., family obligation; emotional support; family as referent), it may be that different dimensions are associated with different socialization messages or behavioral manifestations that may uniquely impact child development (Ramirez & Arce, 1981). Recent work indicates that familismo manifests in various ways among extended family members, including financial support, shared daily activities, shared living, shared childrearing, and immigration support (Calzada et al., 2012b). Familistic behaviors, then, may range from giving up one's paycheck for the sake of the group, which may ultimately compromise healthy child development, to accompanying a family member to a doctor's appointment, which may be unrelated or positively related to healthy child development. Limited research exists on the behavioral manifestations of familismo, but future studies should include comprehensive measures of both attitudes and behaviors, especially since behaviors may exert a more proximal influence on young children's development.

The present study had other noteworthy limitations. Given our use of cross-sectional data, we were not able to examine associations between familismo and child functioning over time. We are currently collecting follow-up data to establish whether familismo exerts a meaningful and long-lasting influence on children, especially as trajectories of mental health become more defined. In alignment with current theories that depict cultural values as dynamic and fluid across time and developmental stage (Calzada et al., 2012b), we will also consider changes in familismo. Future studies should also examine familismo from the perspective of other family members and especially fathers. Past studies indicate that discrepancies between family members on cultural values may contribute to family conflict and stress, compromising healthy developmental outcomes (Baumann et al., 2010; Coatsworth et al., 2000). It might also be that if mothers are highly familistic but fathers are not (or vice versa), the effects of familismo are mitigated or wiped out altogether. In addition, the present results cannot be generalized to other Latino populations, including to later-generation MA families residing in more established receiving communities (e.g., in the Western US) where long-standing ethnic enclaves may influence the attitudes and behaviors associated with familismo. Indeed, many studies with MA families from traditional receiving communities have found familismo to be protective (e.g., Gil, Wagner, & Vega, 2000; German, Gonzales, & Dumka, 2009; Horton & Gil, 2008; Marsiglia, Parsai, & Kulis, 2009). Finally, while our selection of potential moderators (i.e., child gender, poverty, mother's acculturative status) was guided by past research, we did not have data on other important contextual characteristics, including financial strain and social support; these will be important to examine in future research.

Though much is left to learn about the role of familismo in children's development, and particularly about how familismo manifests and exerts its influence uniquely depending on the ecological context of a specific ethnic group, the present study suggests a complex interplay of familial characteristics and cultural values that contributes to protection, and in some cases risk, for young children of MA and DA immigrant mothers across various domains of functioning, but particularly in adaptive skills. For DA children, familismo appeared to offset numerous risks, especially those associated with poverty and the cultural detachment that accompanies a low sense of identity in their mothers. For MA children, familismo appeared to exacerbate some of the risks associated with poverty, compromising adaptive behavior that serves as the foundation of strong interpersonal relationships. Thus, future studies should avoid conceptualizing familismo as unequivocally protective and explore both its potential protective and risk functions. In addition, prevention programs should avoid uniformly promoting adherence to familismo, which may inadvertently reinforce underlying risk processes. Programs that follow a more cautious approach in which the costs and benefits of familismo are carefully explored and understood within the context of the developmental goals for a given child may be more promising in promoting the well-being of Latino children.

References

- Arditti J. Editor's Note. Family Relations: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies. 2006;55:263–265. [Google Scholar]

- Baca-Zinn M, Wells B. Diversity within Latino families: New lessons for family social science. In: Demo DH, Allen KR, Fine MA, editors. Handbook of family diversity. Oxford University Press; New York: 2000. pp. 252–273. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann A, Kuhlberg J, Zayas L. Familism, mother-daughter mutuality, and suicide attempts of adolescent Latinas. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24(5):616–624. doi: 10.1037/a0020584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergad LW. The Latino population of New York City, 1990-2010. Center for Latin American, Caribbean & Latino Studies. CUNY Graduate Center; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, Corwyn RF. Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002;53(1):371–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks AJ, Stuewig J, LeCroy CW. A family based model of Hispanic adolescent substance use. Journal of Drug Education. 1998;28:65–86. doi: 10.2190/NQRC-Q208-2MR7-85RX. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderón-Tena CO, Knight GP, Carlo G. The socialization of prosocial behavioral tendencies among Mexican American adolescents: The role of familism values. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2011;17:98–106. doi: 10.1037/a0021825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzada EJ, Huang KY, Brotman LM. Paper presentation to the Society for Research on Child Development Special Theme conference. Tampa, FL.: 2012. February). Protective effects of familismo on Latino early childhood functioning. [Google Scholar]

- Calzada EJ, Tamis-LeMonda CS, Yoshikawa H. Familismo in Mexican and Dominican families from low-income, urban communities. Journal of Family Issues. 2012 doi: 10.1177/0192513X12460218. [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth JD, Pantin H, McBride C, Briones E, Kurtines W, Szapocznik J. Ecodevelopmental correlates of behavior problems in young Hispanic females. Applied Developmental Science. 2000;6:126–143. doi:10.1207/S1532480XADS0603_3. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado MY, Updegraff KA, Roosa MW, Umaña-Taylor AJ. Discrimination and Mexican-origin adolescents’ adjustment: The moderating roles of adolescents, mothers, and fathers cultural orientations and values. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40:125–139. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9467-z. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmond M, López-Turley RN. The role of familism in explaining the Hispanic-White college application gap. Social Problems. 2009;56:311–334. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Malone P, Lansford JE, Miller S, Pettit GS, Bates JE. A dynamic cascade model of the development of substance-use onset. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2009;74:1–120. 5. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2009.00528.x. Serial No. 294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esparza P, Sanchez B. The role of familism in academic outcomes: A study of urban, Latino high school seniors. Cultural Diversity & Ethic Minority Psychology. 2008;14:193–200. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.3.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrada-Martinez LM, Padilla MB, Caldwell CH, Schulz AJ. Examining the influence of family environments on youth violence: A comparison of Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, non-Latino Black, and non-Latino White adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40:1039–1051. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9624-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Tseng V, Lam M. Attitudes toward family obligations among American adolescents with Asian, Latin American, and European backgrounds. Child Development. 1999;70:1030–1044. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00075. [Google Scholar]

- Gamble W, Modry-Mandell K. Family relations and the adjustment of young children of Mexican descent: Do family cultural values moderate these associations? Social Development. 2008;17:358–379. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Coll C, Lamberty G, Jenkins R, McAdoo HP, Crnic K, Wasik BH, Vazquez Garcia H. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development. 1996;67:1891–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German M, Gonzales N, Dumka L. Familism values as a protective factor for Mexican-origin adolescents exposed to deviant peers. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2009;29:16–42. doi: 10.1177/0272431608324475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil A, Wagner E, Vega W. Acculturation, familism and alcohol use among Latino adolescent males: Longitudinal relations. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28:443–458. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, German M, Kim SY, George P, Fabrett FC, Millsap R, Dumka LE. Mexican American adolescents’ cultural orientation, externalizing behavior and academic engagement: The role of traditional cultural values. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;41:151–164. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9152-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Knight GP, Morgan-Lopez AA, Saenz D, Sirolli A. Acculturation and the mental health of Latino youths: An integration and critique of the literature. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the United States: Current research and future directions. Praeger; Westport, CT: 2002. pp. 45–74. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison AO, Wilson MN, Pine CJ, Chan SQ, Buriel R. Family ecologies of ethnic minority children. Child Development. 1990;61:347–362. [Google Scholar]

- Helms JE, Jernigan M, Mascher J. The meaning of race in psychology and how to change it. American Psychologist. 2005;60:27–36. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.1.27. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton EG, Gil A. Longitudinal effects of family factors on alcohol use among African American and White non-Hispanic males during middle school. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2008;17:57–73. [Google Scholar]

- Huang KY, Caughy MO, Miller TL, Genevro JL. Maternal knowledge of child development and quality of parenting among white, African American and Hispanic mothers. Applied Developmental Psychology. 2005;26:149–170. [Google Scholar]

- Kamphaus RW, Reynolds CR, Hatcher NM. Treatment planning and evaluation with the BASC: The Behavioral Assessment System for Children. In: Maurish E, editor. The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment. 2nd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 1999. pp. 563–597. [Google Scholar]

- Keefe SE. Real and ideal extended familism among Mexican Americans and Anglo Americans: On the meaning of close family ties. Human Organization. 1984;43:65–69. [Google Scholar]

- Keefe SE, Padilla AM, Carlos ML. The Mexican American extended family as an emotional support system. Spanish Speaking Mental Health Research Center Monograph Series. 1978;7:49–67. [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Gonzales NA, Saenz DS, Bonds DD, German M, Deardorff J, Roosa MW, Updegraff KA. The Mexican American cultural value scales for adolescents and adults. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2010;30:444–481. doi: 10.1177/0272431609338178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaRoche MJ, Shriberg D. High stakes exams and Latino students: Toward a culturally sensitive education for Latino children in the United States. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation. 2004;15:205–233. [Google Scholar]

- Lee LC, Halpern CT, Hertz-Picciotto I, Martin SL, Suchindran CM. Child care and social support modify the association between maternal depressive symptoms and early childhood behaviour problems: A US national study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2006;60:305–10. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.040956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loukas A, Prelow HM. Externalizing and internalizing problems in low-income Latino early adolescents: Risk, resources, and protective factors. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2004;23:250–273. [Google Scholar]

- Lugo Steidel A, Contreras J. A new familism scale for use with Latino populations. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2003;25:312–330. [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, Parsai M, Villar P, Garcia C. Cohesion and conflict: Family influences on adolescent alcohol use in immigrant Latino families. Journal of Ethnicity and Substance Use. 2009;8:400–412. doi: 10.1080/15332640903327526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Parsai M, Kulis S. Effects of familism and family cohesion on problem behaviors among adolescents in Mexican immigrant families in the Southwest United States. Journal of Ethnic And Cultural Diversity in Social Work. 2009;18:203–220. doi: 10.1080/15313200903070965. doi:10.1080/15313200903070965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morcillo C, Duarte CS, Shen S, Blanco C, Canino G, Bi HB. Parental familism and antisocial behaviors: Development, gender, and potential mechanisms. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50(5):471–479. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen BO, Satorra A. Complex sample data in structural equation modelling. In: Marsden P, editor. Sociological Methodology. American Sociological Association; Washington, DC: 1995. pp. 267–316. [Google Scholar]

- Niemeyer AE, Wong MM, Westerhaus KJ. Parental involvement, familismo, and academic performance in Hispanic and Caucasian adolescents. North American Journal of Psychology. 2009;11:613–632. [Google Scholar]

- Nolle AP, Gulbas L, Kuhlberg JA, Zayas LH. Sacrifice for the sake of the family: Expressions of familism by Latina teens in the context of suicide. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2012;82(3):319–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2012.01166.x. doi:10.1111/j.1939-0025.2012.01166.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell L, O'Donnell C, Wardlaw DM, Stueve A. Risk and resiliency factors influencing suicidality among urban African American and Latino youth. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2004;33:37–49. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000014317.20704.0b. doi:10.1023/B:AJCP.0000014317.20704.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pabon E. Hispanic adolescent delinquency and the family: A discussion of sociocultural influences. Adolescence. 1998;33:941–955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peña JB, Kuhlberg JA, Zayas LH, Baumann AA, Gulbas L, Hausmann-Stabile C, Nolle AP. Familism, Family Environment, and Suicide Attempts among Latina Youth. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2011;41:330–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2011.00032.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2011.00032.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Horenczyk G, Liebkind K, Vedder P. Ethnic Identity, immigration, and well-being: An interactional perspective. Journal of Social Issues. 2001;57:493–510. doi: 10.1111/0022-4537.00225. [Google Scholar]

- Portes PR. Social and Psychological Factors in the Academic Achievement of Children of Immigrants: A Cultural History Puzzle. American Educational Research Journal. 1999;36:489–507. doi: 10.3102/00028312036003489. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez O, Arce CH. The contemporary Chicano family: An empirically based review. In: Baron A Jr., editor. Explorations in Chicano Psychology. Prager; New York: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban DA, Coatsworth JD, Briones E, Kurtines W, Szapocznik J. Beyond Acculturation: An Investigation of the Relationship of Familism and Parenting to Behavior Problems in Hispanic Youth. Family Process. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2012.01414.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2012.01414.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL, Hernandez Jarvis L. Ethnic identity and acculturation in Hispanic early adolescents: Mediated relationships to academic grades, prosocial behaviors, and externalizing symptoms. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13:364–373. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.4.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherraden MS, Barrera R. Family support and birth outcomes among second-generation Mexican immigrants. Social Service Review. 1997;71:607–633. [Google Scholar]

- Shih RA, Miles JN, Tucker JS, Zhou AJ, D'Amico EJ. Racial/ethnic differences in adolescent substance use: mediation by individual, family, and school factors. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;71:640–651. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih RA, Miles JN, Tucker JS, Zhou AJ, D'Amico EJ. Racial/ethnic differences in the influence of cultural values, alcohol resistance self-efficacy, and alcohol expectancies on risk for alcohol initiation. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26:460–470. doi: 10.1037/a0029254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smokowski PR, Bacallao ML. Acculturation, internalizing mental health symptoms, and self-esteem: Cultural experiences of Latino adolescents in North Carolina. Child Psychiatry Dev. 2007;37:273–292. doi: 10.1007/s10578-006-0035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Orozco C, Suarez-Orozco M. Children of Immigration. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Prado G, Burlew AK, Williams RA, Santisteban DA. Drug abuse in African American and Hispanic adolescents: Culture, development, and behavior. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007;3:77–105. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091408. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.0-22806.091408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdez V, Rodriguez JE. Statistics for Latino majority schools in the Chicago public schools: Pt. 1. Chicagoland Latino Educational Research Institute; Chicago: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela A. Subtractive schooling: U.S.-Mexican youth and the politics of caring. SUNY Press; NY: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Velez W. High school attrition among Hispanic and non-Hispanic White youths. Sociology of Education. 1989;62:119–133. [Google Scholar]

- Venegas J, Cooper TV, Naylor N, Hanson BS, Blow JA. Potential Cultural Predictors of Heavy Episodic Drinking in Hispanic College Students. The American Journal on Addictions. 2012;21:145–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2011.00206.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2011.00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa H. Immigrants raising citizens: Undocumented parents and their young children. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zea MC, Asner-Self KK, Birman D, Buki LP. The abbreviated multidimensional acculturation scale: Empirical validation with two Latino/Latina samples. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2003;9:107–126. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.9.2.107. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.9.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]