Abstract

The mechanisms of photosynthetic adaptation to different combinations of temperature and irradiance during growth, and especially the consequences of exposure to high light (2000 µmol m–2 s–1 PPFD) for 5 min, simulating natural sunflecks, was studied in bean plants (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). A protocol using only short (3 min) dark pre‐treatment was introduced to maximize the amount of replication possible in studies of chlorophyll fluorescence. High light at low temperature (10 °C) significantly down‐regulated photosynthetic electron transport capacity [as measured by the efficiency of photosystem II (PSII)], with the protective acclimation allowing the simulated sunflecks to be used more effectively for photosynthesis by plants grown in low light. The greater energy dissipation by thermal processes (lower Fv′/Fm′ ratio) at low temperature was related to increased xanthophyll de‐epoxidation and to the fact that photosynthetic carbon fixation was more limiting at low than at high temperatures. A key objective was to investigate the role of photorespiration in acclimation to irradiance and temperature by comparing the effect of normal (21 kPa) and low (1·5 kPa) O2 concentrations. Low [O2] decreased Fv/Fm and the efficiency of PSII (ΦPSII), related to greater PSII down‐regulation in cold pre‐treated plants, but minimized further inhibition by the mild ‘sunfleck’ treatment used. Results support the hypothesis that photorespiration provides a ‘safety‐valve’ for excess energy.

Key words: Phaseolus vulgaris L., bean, low temperature, photosynthesis, down‐regulation, high light, sunfleck, chlorophyll fluorescence

INTRODUCTION

In many habitats, crop and native plants are periodically exposed to low temperatures; this can significantly reduce their productivity (e.g. Buis et al., 1988; Fryer et al., 1995; Greaves, 1996; Haldiman, 1998). Among the many physiological mechanisms responsible for this is the potential for damage to the photosynthetic apparatus caused by high light (Baker, 1994; Jones and Demmers‐Derks, 1999). A combination of low temperature and light stress is thought to lead to photoinhibition and photo‐oxidation since the normal route for dissipation of absorbed radiant energy by photosynthetic carbon metabolism is inhibited by low temperature (Baker, 1996). Although the reductions in the efficiency of electron transport through photosystem II (PSII) that have been observed under such conditions have been termed photoinhibition, this term is now more commonly reserved for actual long‐term damage to the photosynthetic system, including the D1 protein, or other reductions in efficiency not reversible over an hour or so (e.g. Maxwell and Johnson, 2000). In many cases, the reduction in efficiency of electron transport through PSII is more appropriately considered to be an acclimatory down‐regulation involving reversible metabolic adjustment to the new conditions, reducing the production of potentially damaging reductants. This down‐regulation can be readily reversible as in the case of some ΔpH‐mediated high energy quenching or state transitions (Horton et al., 1996), or it may decay more slowly over periods from 30 min to several hours.

The capacity of plants to tolerate low temperatures, and to adapt to them, varies among plant species and cultivars. The ability of French bean plants to tolerate short periods of high irradiance (simulating natural sunflecks) under conditions when utilization of the reducing power generated by photosynthetic electron transport in carbohydrate production and growth is limited by low temperatures is investigated in this paper. Absorption of excess light can be deleterious because it leads to increased production of singlet oxygen and reduced reactive oxygen species; these react with, and damage, proteins and other components of photosystems leading to true photoinhibitory damage. Critical conditions of low temperature and high light are commonly experienced by arctic or alpine species in their short summer (Jones and Demmers‐Derks, 1999) and by crop species in temperate zones on cold spring mornings. In such situations, controlled dissipation of excess excitation energy absorbed by the chlorophylls is essential to protect the photosynthetic apparatus. French bean was chosen for the present study because there is a substantial background literature on temperature/photoinhibition responses of this species, which provides a good comparative basis for the present extension to realistic sunfleck treatments. Furthermore, it is an important crop whose growth in temperate regions is significantly restricted by sensitivity to low temperatures (e.g. Nishida and Murata, 1996). This sensitivity is compounded by photoinhibition at high light (as shown here and elsewhere). Nevertheless, the sensitivity can be modulated and there is good evidence that Phaseolus can undergo substantial hardening or acclimatization to low temperatures (e.g. El‐Saht, 1998). There is also genetic variability in tolerance to low temperatures (Melo et al., 1997). The prime purpose of this paper, however, was to investigate the interacting effects of light environment and temperature on photosynthesis.

Factors that enhance photoinhibition at low temperature include reduced utilization of energy in photosynthetic carbon metabolism; restricted rates of D1 protein turnover; decreased xanthophyll cycle activity; and inadequate rates of removal of active oxygen species (Krause, 1994a). The effect of oxygen on the separate processes of photoinhibition and photosynthetic down‐regulation is poorly understood because of its dual role (Krause, 1994b). On the one hand it has protective effects through photorespiration and the Mehler reaction (e.g. Osmond and Grace, 1995), although Ruuska et al. (2000) have suggested that the Mehler reaction may have less effect than once thought. On the other hand, oxygen promotes photoinhibition mainly by triggering D1 degradation and by increasing the probability of forming reactive oxygen species such as the superoxide anion radical (Brestic et al., 1995; Wiese et al., 1998).

Another important aspect of down‐regulation is the degree to which acclimatization to cold may enhance protective mechanisms. Acclimatization of the photosynthetic apparatus to low temperature and to high light is well documented but the mechanisms are still unclear. These include increased capacity of carbon assimilation at low temperature and increased activities of scavenger systems. Öquist et al. (1993a, b) reported that irrespective of temperature (0–25 °C) or the state of cold‐hardiness, the susceptibility of photosynthesis in cereals to photoinhibition is controlled by the redox state of QA, the primary PSII acceptor. These authors suggested that the primary reason for photoinhibition at low temperature is an increase in the proportion of closed reaction centres due to slower rates of CO2 assimilation at low temperature.

Many previous studies of the effects of high light at low temperatures have either used plants grown in growth chambers at unrealistically low irradiances (much lower than those in most natural environments), or have used ‘photoinhibitory’ treatments with much higher irradiances than expected in natural environments (where irradiances of approx. 2000 µmol m–2 s–1 are rarely exceeded). Therefore, the main objectives of this study were to investigate the capacity and control of photosynthetic down‐regulation in bean plants grown at irradiances representative of natural environments and in response to realistic simulated sunflecks. Responses were compared in plants grown at normal (22 °C) and low (10 °C) temperatures after acclimation to different growth irradiances for 6 d. A particular aim was to determine the relative importance of different fates for the absorbed radiative energy, and especially the potential role of oxygen and photorespiration in modulating the response of photosynthetic apparatus in plants pre‐treated in cold conditions.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Bean plants (Phaseolus vulgaris L. ‘Arcadia’) were grown in 15 cm pots containing standard horticultural soil in a glasshouse at 22 °C. After 15 d, plants were divided into groups and were kept for 6 d in a Sanyo (970/C/HQI; Gallenkamp, Loughborough, UK) growth chamber with 12 h days under the following temperature (°C) and light (PPFD, µmol m–2 s–1) regimes: 10/100, 10/1000, 22/100 and 22/1000. Relative humidity was maintained close to 60 %. The high irradiance treatment was more representative of many field environments than the more usual growth chamber environments of 350 µmol m–2 s–1 or less (e.g. Öquist et al., 1992; Öquist and Huner, 1993). Chlorophyll fluorescence and gas exchange were measured 2, 4 and 6 d after moving plants into the chamber. Pigment contents and catalase and peroxidase activities were determined at the end of the treatment period. The effect on photosynthesis of a 5‐min period of high irradiance (2000 µmol m–2 s–1), simulating a sunfleck, was studied on the sixth day. This irradiance is close to the maximum likely to be experienced by a leaf exposed to full sunlight (Jones, 1993). Two independent experiments for each growth temperature were carried out giving four to eight replications for all variables measured. Staggered plantings allowed further replications on other dates in each experiment.

Chlorophyll fluorescence

Chlorophyll fluorescence was measured using a modulated system (FMS; Hansatech Ltd, Kings Lynn, UK). Initial (F0) and maximal (Fm) fluorescence yields were measured on leaves that had been dark adapted for 30 min in the growth chamber. Other parameters of chlorophyll fluorescence kinetics were measured in separate experiments using the environmentally controlled leaf chamber of a portable photosynthesis system (Ciras‐1; PP Systems, Hoddesdon, UK) at normal (21 kPa) or decreased (1·5 kPa) concentrations of O2, and at normal (22 °C) and low (10 °C) temperature using the following protocol: after insertion of the leaf in the chamber there was an initial 4‐min illumination at the appropriate growth irradiance (100 or 1000 µmol m–2 s–1), at the end of which CO2 assimilation and steady‐state fluorescence (Fs) were determined and a saturating pulse (approx. 5000 µmol m–2 s–1) was given to obtain Fm′ (quenched maximal fluorescence). The actinic light was switched off and a 5‐s pulse of weak far‐red light (735 nm) was applied to give F0′ (light‐adapted initial fluorescence) for calculation of ΦPSII (the quantum yield of PSII). After 3 min dark adaptation and measurement of F0 followed by Fm, the sample was treated with high light (2000 µmol m–2 s–1) for 5 min, at the end of which CO2 assimilation, Fs, Fm′ and F0′ were measured as before. After a further 30 s in the dark, a saturating pulse was applied, followed by 5 s of weak far‐red light to estimate Fm and F0. On the sixth day only, the dark recovery period was extended by the use of saturating flashes followed by far‐red pulses after further periods in the dark of 0·5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 8and 11 min (giving a total of 35 min recovery). Gas mixtures were obtained using Hastings Mass Flow controllers (Hampton, VA, USA) and stored in PVC beach balls until required, with CO2 partial pressure maintained at 31 Pa except where CO2‐response curves were studied.

A 3‐min initial dark adaptation was used to facilitate replication; this gave generally similar Fv/Fm values to the more usual 20–30 min treatment (e.g. compare Fig. 1 and Table 1), although there was some evidence that it could underestimate Fv/Fm. In most cases, however, the use of a 3‐min dark period led to only a 2 % reduction in Fv/Fm compared with that obtained following a 30‐min dark period (Fig. 3), although the underestimation did rise to about 9 % for the low temperature/high light treatment, presumably due to slow relaxation.

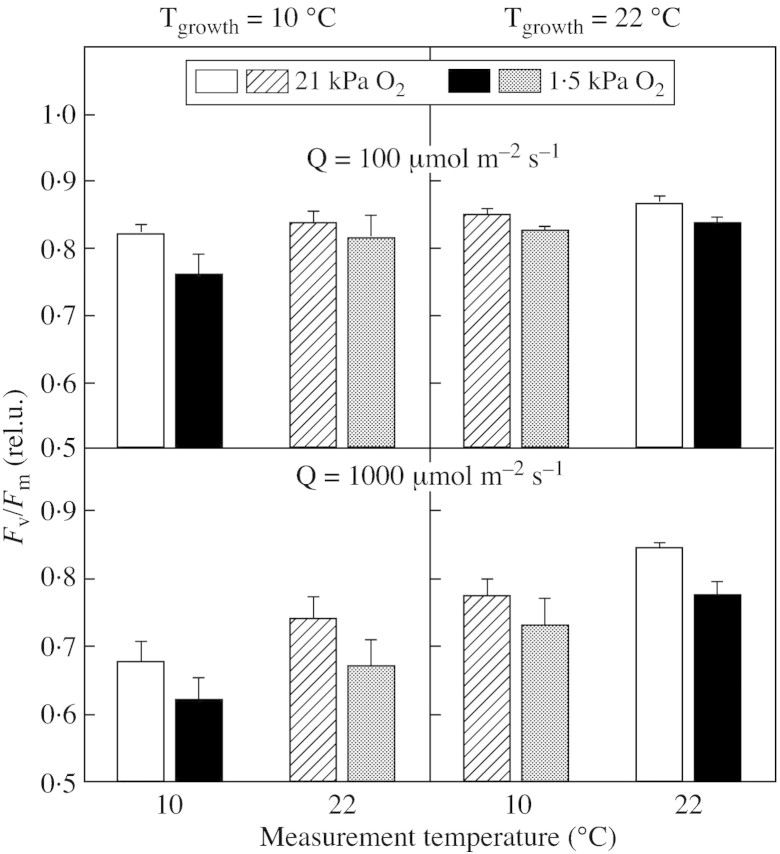

Fig. 1. Variable to maximal chlorophyll fluorescence ratio (Fv/Fm) after 6 d growth at low (10 °C) or high (22 °C) temperature, and either low (100 µmol m–2 s–1) or high (1000 µmol m–2 s–1) irradiance (during the 12 h days). Measurements were made after 3‐min dark adaptation and under a normal (21 kPa) or decreased (1·5 kPa) concentration of O2 in the air. Black and white columns: measurements made at the same temperature as the growth temperature; hatched and stippled columns: measurements made at the contrasting temperature. Mean values ± s.e. of six replications from three independent experiments are presented.

Table 1.

Variable to maximal chlorophyll fluorescence ratio (Fv/Fm), and initial (F0) and maximal (Fm) chlorophyll fluorescence measured on the sixth day of treatment after 30‐min dark adaptation at corresponding growth conditions

| Tmeas. = Tgrowth (°C) | Imeas. = Igrowth (µmol m–2 s–1) | Fv/Fm (relative units) | F0 (relative units) | Fm (relative units) |

| 10 | 100 | 0·815 ± 0·0035b | 56 ± 1·2b | 304 ± 3·2c |

| 10 | 1000 | 0·748 ± 0·0094a | 54 ± 1·1b | 219 ± 9·6a |

| 22 | 100 | 0·849 ± 0·0016c | 50 ± 0·9b | 330 ± 7·2d |

| 22 | 1000 | 0·837 ± 0·0032bc | 38 ± 1·1a | 241 ± 7·0b |

Mean values ± s.e. of 12 replications from three independent experiments are presented. Values followed by the same letter do not differ significantly at P = 0·05 according to the LSD test.

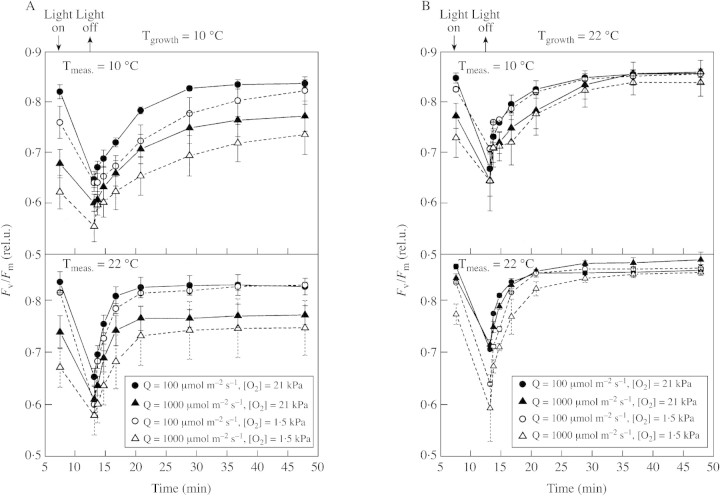

Fig. 3. Time course of recovery of Fv/Fm after 5‐min ‘sunfleck’ treatment (2000 µmol m–2 s–1 PPFD) A, Growth temperature: 10 °C. B, Growth temperature: 22 °C. Mean values ± s.e. of six replications from three independent experiments are presented.

CO2 exchange

Rates of CO2 assimilation and stomatal conductance were measured using the portable photosynthesis system (Ciras‐1) 2 and 4 d after transfer of the plants to the growth chamber under irradiances (measured within the leaf cuvette) corresponding to growth light at normal (21 kPa) and decreased (1·5 kPa) concentrations of O2, and at normal (22 °C) and low (10 °C) temperatures. Light‐ (seven points with 4 min adaptation) and CO2‐response (11 points with 3 min adaptation) curves were measured under the same conditions on the sixth day. Respiration rates measured after 35 min in the dark at the two O2 concentrations used were within 5 % of each other at both experimental temperatures and did not differ significantly.

Pigment extraction and analysis

Leaves were killed in liquid nitrogen, ground to a powder and stored at –10 °C until required. Sub‐samples (50 mg) of frozen shoot material were added to 500 µl 100 % methanol in a 1·5 ml Eppendorf vial and mixed for 1 min. A further 500 µl 100 % methanol was added and the mixture mixed for 1 min, after which it was spun down for 10 min at 11 500 rpm. The supernatant was decanted and the resultant pellet resuspended in 500 µl 100 % methanol, mixed for 1 min, and spun down for 10 min at 11 500 rpm. This was repeated once more, giving an extraction dilution of 25 mg f. wt shoot material per ml methanol. Samples were stored at –30 °C until analysis.

Chlorophylls a and b, β‐carotene, lutein, neoxanthin, violaxanthin, antheraxanthin and zeaxanthin were quantified by high pressure liquid chromatography using a protocol based on that of Tsavalos et al. (1993). The reversed‐phase system consisted of a Waters C18 radial compression module (4 µm; 8 × 100 mm) with a 200‐mm C18 guard column using a solvent gradient of 10–100 % ethyl acetate in acetonitrile : water (9 : 1,v/v) over 25 min at a flow rate of 1·0 ml min–1. Violaxanthin, antheraxanthin and zeaxanthin peaks were identified and quantified with standard pigments supplied by VKI (Agern Allé 11, DK‐2970 Hørsholm, Denmark). All other pigments were collected by fractionation, and identified and quantified spectrophotometrically using reference spectra and extinction coefficients (Jeffrey et al., 1997). The de‐epoxidation state (deps) of the xanthophyll cycle pigments, violaxanthin (V), antheraxanthin (A) and zeaxanthin (Z) was calculated as: deps = (A + Z)/(V + A + Z) (see Demmig‐Adams and Adams, 1996).

Statistical analysis

Analysis of variance and other statistical tests were conducted using Minitab 12.1 (Minitab Inc., State College, PA, USA). Differences between treatments were assessed using ANOVA and least significant differences (Snedecor and Cochrane, 1999).

RESULTS

Chlorophyll fluorescence

The photochemical efficiency of PSII, assessed as Fv/Fm after a 30‐min dark pre‐treatment under normal growth conditions (Table 1) was close to the expected maximum for plants grown at low light. However, at least at low temperature, there was evidence for photoinhibition or down‐regulation at high light, resulting mainly from a decrease in Fm with non‐significant changes in F0.

Figure 1 summarizes the effects of growth temperature, measurement temperature, irradiance and oxygen concentration on Fv/Fm measured using a 3‐min dark period. Results were generally similar to those obtained using the standard 30‐min pre‐treatment (compare Fig. 1 and Table 1; detailed results not shown) so all subsequent data presented use the abbreviated 3‐min dark protocol to allow maximal replication. As there were few significant trends over the 6 d (except for plants in the high temperature/high light treatment in which Fv/Fm increased from 0·76 on day 2 to 0·84 on day 6; P < 0·05), data for on the 3 d of measurements have been averaged. The key observation was that Fv/Fm measured in 1·5 kPa O2 was consistently lower (by 2–9 %) than that measured in normal oxygen (main effect P < 0·01).

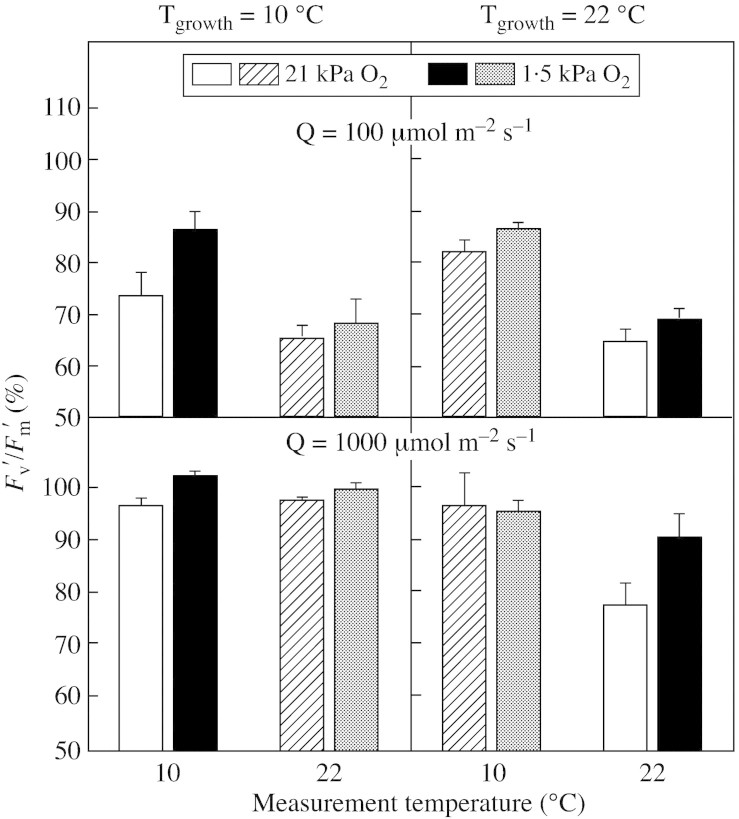

The further inhibitory effect of 2000 µmol m–2 s–1 PPFD for 5 min is shown in Fig. 2 where the efficiency of the open PSII reaction centres, Fv′/Fm′, is plotted as a percentage of the Fv′/Fm′ ratio before the high‐light treatment. It is evident that the decline of Fv′/Fm′ was greater for plants grown at low PPFD and that the inhibition was less at low O2 concentration than at normal O2.

Fig. 2.Fv′/Fm′ at the end of a 5‐min ‘sunfleck’ treatment (2000 µmol m–2 s–1 PPFD) as a percentage of the value before treatment for plants grown at low (10 °C) or high (22 °C) temperatures and under normal (21 kPa) or decreased (1·5 kPa) concentrations of O2 in the air. Black and white columns: measurements made at the same temperature as the growth temperature; hatched and stippled columns: measurements made at the contrasting temperature. Mean values ± s.e. of six replications from three independent experiments are presented.

In all treatments the quantum yield of PSII (ΦPSII, Table 2) was smaller when measured at low O2 concentration, and was much greater at low light compared with high light. However, after the simulated sunfleck treatment, ΦPSII was lower in the low‐light‐adapted than the high‐light‐adapted plants. The reduction in ΦPSII averaged 86 % for low‐light‐adapted plants and only 44 % for the high‐light‐adapted plants.

Table 2.

Steady‐state quantum yield of PSII under growth conditions (ΦPSII‐steady), together with values of ΦPSII, qP and NPQ (ΦPSII*, qP* and NPQ*) at the end of the 5‐min high‐light treatment

| Tgrowth (°C) | Igrowth (µmol m–2 s–1) | O2 (kPa) | ΦPSII‐steady (relative units) | ΦPSII*(relative units) | qP* (relative units) | NPQ* |

| 10 | 100 | 21 | 0·63 ± 0·01 | 0·07 ± 0·01 | 0·17 ± 0·02 | 2·15 ± 0·35 |

| 10 | 100 | 1·5 | 0·41 ± 0·08 | 0·06 ± 0·00 | 0·15 ± 0·01 | 1·50 ± 0·59 |

| 10 | 1000 | 21 | 0·15 ± 0·02 | 0·14 ± 0·02 | 0·23 ± 0·08 | 0·61 ± 0·41 |

| 10 | 1000 | 1·5 | 0·12 ± 0·01 | 0·10 ± 0·00 | 0·19 ± 0·01 | 0·24 ± 0·11 |

| 22 | 100 | 21 | 0·78 ± 0·01 | 0·13 ± 0·01 | 0·30 ± 0·09 | 2·48 ± 0·48 |

| 22 | 100 | 1·5 | 0·75 ± 0·01 | 0·10 ± 0·01 | 0·25 ± 0·04 | 2·40 ± 0·16 |

| 22 | 1000 | 21 | 0·43 ± 0·05 | 0·18 ± 0·02 | 0·55 ± 0·08 | 2·14 ± 0·12 |

| 22 | 1000 | 1·5 | 0·26 ± 0·02 | 0·12 ± 0·03 | 0·37 ± 0·23 | 1·40 ± 0·13 |

All values ( ± s.e.) were averaged over the 3 d of measurement at O2 concentrations of either 21 or 1·5 kPa.

In several cases an enhanced steady‐state chlorophyll fluorescence yield (Fs) was observed in plants grown in low light at the end of the 5‐min high‐light treatment, with the average increase being 27 ± 3 % (P = 0·0056). There were, however, no differences in the responses at low and normal O2 concentrations (data not shown). There were also no differences in photochemical quenching (qP) between plants grown at low and high light, but qP was lower (by 20 %) when measured at low O2 concentration (Table 2). The non‐photochemical quenching (NPQ) was greatly decreased by high light, especially at low temperatures, and was also decreased at low O2 concentration by an average of 32 % (Table 2).

Relaxation of Fv/Fm after the 5‐min sunfleck treatment was rapid and was more or less complete within 20–30 min (Fig. 3), indicating that any effect of the treatment on Fv/Fm represented true down‐regulation rather than photoinhibitory damage. The slightly higher final values of Fv/Fm compared with those prior to the photoinhibitory treatment probably result from the short dark period (3 min) used for the first (reference) Fm measurement. A characteristic distinction in the relaxation between plants grown at low and high temperature is the difference between treatments in the first case (P < 0·01) and the lack of differences in the second. The rate of recovery of PSII upon darkening was clearly faster at high temperatures.

Gas exchange

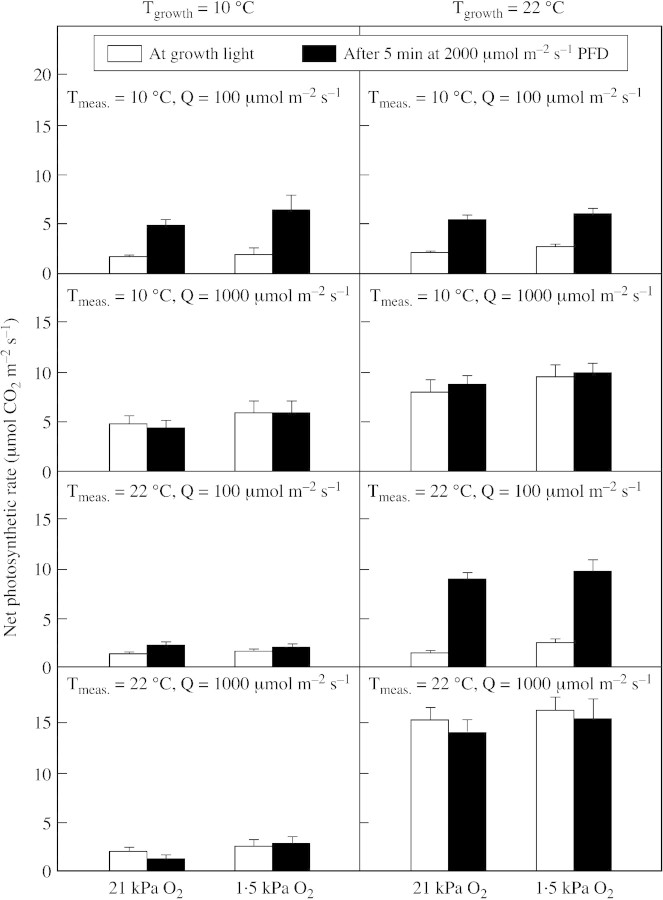

The changes in net photosynthetic rate before and after the 5‐min high light treatment (Fig. 4) generally correlate with the observed changes in ΦPSII, except for plants grown at 10 °C and treated at 22 °C whose photosynthetic rate was low. This was related to the abnormally low stomatal conductances achieved in these particular treatments. For example, the 10/22 °C plants had a conductance of 45 ± 10 mmol m–2 s–1 compared with 460 ± 50 mmol m–2 s–1 in the plants grown and measured at 22 °C. The net photosynthetic rate measured at 2000 µmol m–2 s–1 in plants grown at 22 °C and low light was lower than that in plants grown at the same temperature under high light.

Fig. 4. Net photosynthetic rate at growth light and at the end of 5‐min ‘sunfleck’ treatment (2000 µmol m–2 s–1 PPFD) measured under a normal (21 kPa) or decreased (1·5 kPa) concentration of O2. Mean values ± s.e. of six replications from three independent experiments are presented.

Pigment content

For plants grown at both high and low temperatures for 6 d the total Chl content was significantly lower in plants grown at high light than those grown at low light (Table 3). The ratio of chlorophyll a/b did not change significantly as a result of low‐temperature or high‐light treatment (data not shown). Concentrations of total carotenoids and total xanthophyll were greater for plants grown at low temperature. There were much larger increases in antheraxanthin and zeaxanthin in plants in the high light treatments resulting in a clearly enhanced de‐epoxidation state, with deps reaching 0·78 at high light and low temperature.

Table 3.

Quantities of chlorophyll [in mol g–1 f. wt (×104)], β‐carotene and xanthophylls (lutein, violaxanthin, antheraxanthin, zeaxanthin, neoxanthin) per total Chl and the de‐epoxidation state [(A + Z)/(A + V + Z)]

| Tgrowth (°C) | Igrowth | Chlorophyll | β‐Carotene | Lutein | Violaxanthin | Antheraxanthin | Zeaxanthin | Neoxanthin | (A + Z)/(A + V + Z) | Total xanthophylls | Total carotenoids |

| 10 | 100 | 30·6b | 0·053b | 0·103b | 0·017a | 0·006b | 0·009a | 0·028b | 0·464b | 0·163bc | 0·216ab |

| 10 | 1000 | 23·5a | 0·036a | 0·097b | 0·015a | 0·017c | 0·035c | 0·025ab | 0·777c | 0·188c | 0·224b |

| 22 | 100 | 31·4b | 0·048b | 0·098b | 0·012a | 0·001a | 0·004a | 0·023ab | 0·294a | 0·138ab | 0·186a |

| 22 | 1000 | 25·7a | 0·054b | 0·076a | 0·017a | 0·007b | 0·013b | 0·020a | 0·534b | 0·132a | 0·186a |

| s.e.d. | 1·70 | 0·008 | 0·008 | 0·003 | 0·002 | 0·003 | 0·003 | 0·051 | 0·012 | 0·018 |

Standard errors of difference within columns (s.e.d.) were calculated from ANOVAs (four to five replicates). Within a column, different superscripts indicate values that are significantly different (LSD at P < 0·05).

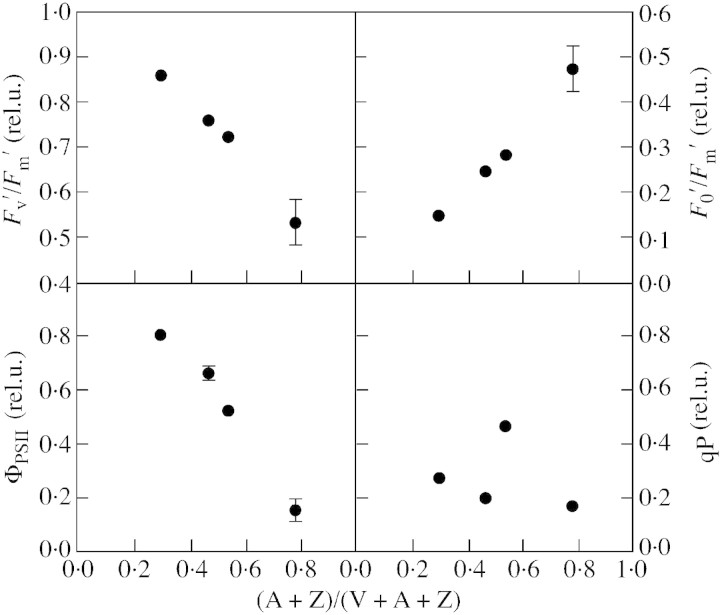

Figure 5 shows the relationship between some characteristics of chlorophyll fluorescence and the deps state of the xanthophyll cycle for the different treatments. A close inverse correlation (R2 = 0·98) existed between the quantum yield of PSII and deps, as well as between the efficiency of open PSII units (Fv′/Fm′) and deps. There was also a very strong correlation (R2 = 0·99) between F0′/Fm′ and the de‐epoxidation state of the xanthophyll cycle.

Fig. 5. Relationship between the chlorophyll fluorescence variablesF′v/F′m, F′0/F′m, ΦPSII and qP, and a measure of the de‐epoxidation state of the xanthophyll cycle components (A+Z)/(V+A+Z). Mean values ± s.e. are presented.

DISCUSSION

A combination of gas‐exchange, chlorophyll fluorescence and biochemical analysis was used to examine changes in photosynthetic responses of French bean plants grown at low or high light to a simulated sunfleck treatment, and the interactions of these responses with temperature and oxygen concentration. The experiment was designed to mimic the effect of sunflecks on such plants in their natural environments, and to determine whether temperature or growth irradiance affect the photosynthetic responses to such sunflecks. Another aim was to determine whether any photosynthetic responses observed were a consequence of photoinhibitory damage to the system or whether they represent protective down‐regulation, and if this depends on growth temperature. The rapid recovery of most photosynthetic variables, including Fv/Fm, on darkening indicates that the observed responses to the sunflecks largely reflected positive regulatory responses which regulate the utilization and dissipation of incident radiant energy, rather than damage to PSII.

A chronic decrease in the efficiency of photosynthetic electron transport through PSII (as indicated by Fv/Fm) was found in bean plants grown at high light and low temperature (Fig. 1), with this effect being largely attributable to the greater reduction in Fm than F0 (Table 1). This can be interpreted as an increase in the rate constant for thermal dissipation (Vavilin et al., 1995; Saccardy et al., 1998) and/or inactivation of reaction centres of PSII (Le Gouallec et al., 1991). The general reduction in both Fm and F0 in the high‐light conditions indicates changes in antenna size which minimize absorbance of incident light (Verhoeven et al., 1996; Neidhardt et al., 1998). Following the simulated sunfleck treatment a further large decrease in quantum efficiency of PSII was observed, especially at low temperature. Note that any effect of this sunfleck treatment had been totally reversed within 20–30 min (Fig. 3).

Several factors could have enhanced down‐regulation at low temperature. The main factor is likely to be the greatly reduced capacity for utilization of incident radiant energy in photosynthetic carbon metabolism (Fig. 4), indicated by the fact that, following a ten‐fold increase in incident light, net assimilation only doubled at low temperature compared with a nearly nine‐fold increase at 22 °C (Fig. 4). Leaves could, therefore, use nearly all the extra energy at high temperature but not at low temperature. Other possible factors include changes in respiratory metabolism (Mawson, 1993), decreased activity of the xanthophyll cycle, insufficient scavenging of active oxygen (Krause, 1994a) and a reduced rate of enzymatic PSII repair processes (Aro et al., 1990). The decrease in the quantum yield (ΦPSII) observed after the sunfleck treatment at low temperature indicates that a decreased fraction of excitation energy absorbed by PSII antennae is utilized in PSII photochemistry, while the reduced efficiency of open PSII units (Fv′/Fm′) is evidence for enhanced energy dissipation in light‐harvesting antennae (Schreiber et al., 1994; Demmig‐Adams and Adams, 1996).

An important aspect of the present experiments was treatment with 1·5 kPa O2 to inhibit photorespiration (PR) but not normal respiratory metabolism or the Mehler reaction (Brestic et al., 1995; Wiese et al., 1998), under the hypothesis that the loss of photorespiration as a sink for electrons might lead to photoinhibitory damage or enhanced down‐regulation (see Ort and Baker, 2002). It is uncertain, however, whether low oxygen actually decreases electron flow, or whether all energy is diverted on a one‐to‐one basis into photosynthetic metabolism (Sharkey and Vassey, 1989; Osmond and Grace, 1995). In all treatments, the ratios Fv/Fm and Fv′/Fm′ measured under 1·5 kPa O2 were smaller than those measured at normal O2 concentration (Fig. 1), suggesting that photorespiration does indeed provide a significant ‘safety‐valve’ for excess energy that cannot be replaced by compensating increased CO2 fixation (Ort and Baker, 2002). Interestingly, however, the further decrease in Fv/Fm after 5 min high‐light treatment (Fig. 2) was greater at 21 kPa O2, with NPQ being smaller. Nevertheless, the absolute value of Fv/Fm remained smaller at low O2 concentrations. According to Goh et al. (1999) the fluorescence‐derived rates of electron transport do not necessarily correspond with the rate of CO2 fixation, and this appears to be the case here. Other forms of electron transport through PSII, such as the Mehler–ascorbate–peroxidase cycle, which depend on O2 as the electron acceptor (Schreiber et al., 1995; Asada et al., 1998; Ort and Baker, 2002) could also contribute to the O2‐sensitivity of the Fv/Fm ratio. This is supported by data for single guard cells (Goh et al., 1999). It is notable that no significant differences were observed in O2 sensitivity of Fv/Fm at low (10 °C) or normal (22 °C) temperature when measured at normal CO2 concentration. Although the effect of reduced CO2 concentrations was not investigated in the present study, Savitch et al. (2000) used combinations of such treatments with reduced O2 concentrations to show that both photorespiration and the Mehler reaction can mitigate the sensitivity to photoinhibition in wheat plants grown in high light. A possible decrease in the chlororespiratory oxidation of the plastoquinone pool as a result of low oxygen should also be considered (Büchel and Garab, 1996).

In some treatments the rates of net CO2 assimilation measured at 1·5 kPa O2 were lower than expected, and did not differ significantly from those measured at 21 kPa O2. These observations are evidence for inhibition of photosynthesis at low oxygen concentrations. Similar effects of sub‐optimal concentrations of O2 were noted by Maroco et al. (1997) in other C4 plants. These authors showed that inhibition of photosynthesis below the optimum was associated with increased reduction of the quinone A pool (QA), decreased efficiency of open reaction centres and decreased activity of PSII. Reduction of ΦPSII, over‐reduction of QA and decreased CO2 assimilation have been reported by Dietz et al. (1985) at low O2 concentrations in the C3 plants Spinacea oleracea, Asarum europaeum and Helianthus annuus. In experiments with bean plants under drought conditions, Brestic et al. (1995) also showed that decreasing the oxygen content of the air from 21 to 2 kPa, to inhibit photorespiration, decreased the linear electron transport rate. A deficiency in ATP caused by over‐reduction of electron carriers limiting cyclic electron flow was proposed as a possible reason for the inhibition of photosynthesis in the absence of O2 in spinach (Ziem‐Hanck and Heber, 1980) and Chroomonas sp. (Suzuki and Ikawa, 1993). However, the mechanisms of inhibition of photosynthetic activity at low O2 partial pressures are not yet clear.

The increase in the ratio of total carotenoids to chlorophyll in response to growth at low temperature was more pronounced at high than at low PPFD. This may reflect an adaptation mechanism permitting plants to reduce light absorption in the antenna on the one hand, and to increase the capacity for photoprotection on the other (Haldiman, 1998). Carotenoids act as scavengers of triplet chlorophyll and singlet oxygen, and the xanthophyll cycle pigments zeaxanthin and antheraxanthin mediate the harmless dissipation of excess excitation energy as heat (Demmig‐Adams and Adams, 1996). The increased contents of zeaxanthin and antheraxanthin in plants grown under 1000 µmol m–2 s–1 PPFD and the consequently enhanced deps were closely correlated with ΦPSII and also with Fv′/Fm′ and F0′/Fm′ (Fig. 5). These results support the hypothesis that xanthophyll cycle activity makes an important contribution to energy quenching in French bean exposed to short periods of very high light (Adams and Demmig‐Adams, 1995; Verhoeven et al., 1997). The increased concentration of β‐carotene could contribute to the fluidization of the chloroplast membrane at low temperature (Strzalka, 1994).

The present data showing a decreased quantum efficiency of PSII and a decreased rate of CO2 assimilation under high light at low temperature are evidence for significant down‐regulation in the photosynthetic apparatus in plants grown in low light. There were also indications of greater oxidative stress in low‐temperature/high‐light conditions, with plants showing an increased H2O2 concentration and slight decreases in the activities of catalase and peroxidase (data not shown). The close correlation between the thermal dissipation in the antenna (1 – Fv′/Fm′) and the de‐epoxidation state of the xanthophyll cycle supports the hypothesis that xanthophyll cycle activity makes an important contribution to quenching of excess energy. Nevertheless, quenching in the reaction centres might also be significant (Bukhov et al., 2001; Peterson and Havir, 2001). Relaxation of this type of quenching tends to be slower than zeaxanthin‐dependent antenna quenching and is indicated by the slow phase relaxation shown for the low temperature/high light treatment in Fig. 3. The significant contribution of Fm to the decline in Fv/Fm also supports this suggestion.

There was no evidence that the simulated sunfleck lasting 5 min led to any irreversible damage to PSII, even for plants grown at low temperature and low light. A low O2 concentration enhanced PSII down‐regulation in cold pre‐treated plants, as expressed by a reduction in Fv/Fm and ΦPSII, but minimized further inhibition by the short sunfleck treatment used. These results support the hypothesis that photorespiration provides a ‘safety‐valve’ for excess energy that cannot be replaced by compensating increased CO2 fixation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by NATO Scientific Division grant LST.CLG 974973. We are grateful to Dr Richard Parsons for help with generating the gas mixtures and to Wendy M. James for technical support.

Supplementary Material

Received: 3 July 2002; Returned for revision: 24 September 2002; Accepted: 21 October 2002 Published electronically: 12 December 2002

References

- AdamsWWIII, Demmig‐Adams B.1995. The xanthophyll cycle and sustained energy dissipation in Vinca minor and Eunymous kiautschovcus in winter. Plant, Cell and Environment 18: 553–561. [Google Scholar]

- AroE‐M, Hundal T, Carlberg I, Andersson B.1990. In vitro studies on light‐induced inhibition of Photosystem II and D1‐protein degradation at low temperatures. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1019: 269–275. [Google Scholar]

- AsadaK, Endo T, Mano J, Miyake C.1998. Molecular mechanism for relaxation and protection from light stress. In: Satoh K, Murata N, eds. Stress responses of photosynthetic organisms Amsterdam: Elsevier, 37–52. [Google Scholar]

- BakerN.1994. Chilling stress and photosynthesis. In: Foyer CH, Mullineaux PM, eds. Causes of photooxidative stress and amelioration of defence systems in plants Boca Raton: CRC Press, 127–154. [Google Scholar]

- BakerN.1996. Environmental constrains on photosynthesis; an overview of some future prospects. In: Baker NR, ed. Advances in photosynthesis, vol. 5. Photosynthesis and environment Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 467–476. [Google Scholar]

- BresticM, Cornic G, Fryer MJ, Baker NR.1995. Does photorespiration protect the photosynthetic apparatus in French bean leaves from photoinhibition during drought stress? Planta 196: 450–457. [Google Scholar]

- BüchelC, Garab G.1996. Respiratory regulation of electron transport in chloroplasts: chlororespiration. In: Pessarakli M, ed. Handbook of photosynthesis New York: Marcel Dekker, 83–93. [Google Scholar]

- BuisR, Barthou H, Roux B.1988. Effect of temporary chilling on foliar and caulinary growth and productivity in soybean (Glycine max). Annals of Botany 61: 705–715. [Google Scholar]

- BukhovNG, Heber U, Wiese C, Shuvalov VA.2001. Energy dissipation in photosynthesis: does the quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence originate from antenna complexes of photosystem II or from the reaction center? Planta 212: 749–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demmig‐AdamsB, Adams WW III.1996. Xanthophyll cycle and light stress in nature: uniform response to excess direct sunlight among higher plant species. Planta 198: 460–470. [Google Scholar]

- DietzK‐J, Schreiber U, Heber U.1985. The relationship between the redox state of QA and photosynthesis in leaves at various carbon‐dioxide, oxygen and light regimes. Planta 166: 219–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El‐SahtHM.1998. Responses to chilling stress in French bean seedlings: antioxidant compounds. Biologia Plantarum 41: 395–402. [Google Scholar]

- FryerMJ, Oxborough K, Martin B, Ort DR, Baker NR.1995. Factors associated with depression of photosynthetic quantum efficiency in maize at low growth temperature. Plant Physiology 108: 761–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GohC‐H, Schreiber U, Hedrich R.1999. New approach of monitoring changes in chlorophyll a fluorescence of single guard cells and protoplasts in response to physiological stimuli. Plant, Cell and Environment 22: 1057–1070. [Google Scholar]

- GreavesJA.1996. Improving suboptimal temperature tolerance in maize—the search for variation. Journal of Experimental Botany 47: 307–323. [Google Scholar]

- HaldimanP.1998. Low growth temperature induced changes to pigment composition and photosynthesis in Zea mays genotypes differing in chilling sensitivity. Plant, Cell and Environment 21: 200–208. [Google Scholar]

- HortonP, Ruban AV, Walters RG.1996. Regulation of light harvesting in green plants. Annual Reviews of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology 47: 665–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JeffreySW, Mantoura RFC, Wright SW.1997. Phytoplankton pigments in oceanography. Paris: UNESCO publishing. [Google Scholar]

- JonesHG.1993. Plants and microclimate, 2nd edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- JonesHG, Demmers‐Derks HHWM.1999. Photoinhibition as a factor in altitudinal or latitudinal limits of species. Phyton 39: 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- KrauseGH.1994a Photoinhibition induced by low temperatures. In: Baker NR, Bowyer JR, eds. Photoinhibition of photosynthesis. From molecular mechanisms to the field Oxford: BIOS Scientific Publishers, 331–348. [Google Scholar]

- KrauseGH.1994b The role of oxygen photoinhibition of photosynthesis. In: Foyer CH, Mullineaux PM, eds. Causes of photooxidative stress and amelioration of defence systems in plants Boca Raton: CRC Press, 43–76. [Google Scholar]

- Le GouallecJ‐L, Cornic G, Briantais J‐M.1991. Chlorophyll fluorescence and photoinhibition in a tropical rainforest understory plant. Photosynthesis Research 27: 135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MarocoJP, Ku MSB, Edwards GE.1997. Oxygen sensitivity of C4 photosynthesis: evidence from gas exchange and fluorescence analysis with different C4 sub‐types. Plant, Cell and Environment 20: 1525–1533. [Google Scholar]

- MawsonBT.1993. Modulation of photosynthesis and respiration in guard and mesophyll cell protoplasts by oxygen concentration. Plant, Cell and Environment 16: 207–214. [Google Scholar]

- MaxwellK, Johnson GN.2000. Chlorophyll fluorescence—a practical guide. Journal of Experimental Botany 51: 659–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MeloLC, dosSantos JB, Ramalho MAP.1997. Choice of parents to obtain common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) cultivars tolerant to low temperatures at the adult stage. Brazil Journal of Genetics 20: 283–292. [Google Scholar]

- NeidhardtJ, Benemann JR, Zhang L, Melis A.1998. Photosystem‐II repair and chloroplast recovery from irradiance stress: relationship between chronic photoinhibition, light‐harvesting chlorophyll antenna size and photosynthetic productivity in Dunaliella salina (green algae). Photosynthesis Research 56: 175–184. [Google Scholar]

- NishidaI, Murata N.1996. Chilling sensitivity in plants and cyanobacteria: the crucial contribution of membrane lipids. Annual Review of Plant Physiology 47: 541–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ÖquistG, Huner NPA.1993. Cold‐hardening‐induced resistance to photoinhibition of photosynthesis in winter rye is dependent upon an increased capacity for photosynthesis. Planta 189: 150–156. [Google Scholar]

- ÖquistG, Hurry VM, Huner NPA.1993a Low‐temperature effects on photosynthesis and correlation with freezing tolerance in spring and winter cultivars of wheat and rye. Plant Physiology 101: 245–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ÖquistG, Hurry VM, Huner NPA.1993b The temperature dependence of the redox state of QA and susceptibility of photosynthesis to photoinhibition. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 31: 683–689. [Google Scholar]

- ÖquistG, Anderson JM, McCaffery S, Chow WS.1992. Mechanistic differences in photoinhibition of sun and shade plants. Planta 188: 422–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OrtDR, Baker NR.2002. A photoprotective role for O2 as an alternative electron sink in photosynthesis? Current Opinion in Plant Biology 5: 193–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OsmondCB, Grace SC.1995. Perspectives on photoinhibition and photorespiration in the field: quintessential inefficiencies of the light and dark reactions of photosynthesis? Journal of Experimental Botany 46: 1351–1362. [Google Scholar]

- PetersonRB, Havir EA.2001. Photosynthetic properties of an Arabidopsis thaliana mutant possessing a defective PsbS gene. Planta 214: 142–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RuuskaSA, Badger MR, Andrews TJ, von Caemmerer S.2000. Photosynthetic electron sinks in transgenic tobacco with reduced amounts of Rubisco: little evidence for significant Mehler reaction. Journal of Experimental Botany 51: 357–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SaccardyK, Pineau B, Roche O, Cornic G.1998. Photochemical efficiency of Photosystem II and xanthophyll cycle components in Zea mays leaves exposed to water stress and high light. Photosynthesis Research 56: 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- SavitchLV, Massacci A, Gray GR, Huner NPA.2000. Acclimation to low temperature or high light mitigates sensitivity to photoinhibition: roles of the Calvin cycle and the Mehler reaction. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology 27: 253–264. [Google Scholar]

- SchreiberU, Bilger W, Neubauer C.1994. Chlorophyll fluorescence as a noninstructive indicator for rapid assessment of in vivo photosynthesis. In: Schulze E‐D, Caldwell MM, eds. Eco physiology of photosynthesis. Ecological studies Berlin: Springer, 49–70. [Google Scholar]

- SchreiberU, Hormann H, Asada K, Neubauer C.1995. O2‐dependent electron flow in intact spinach chloroplasts: properties and possible regulation of the Mehler‐ascorbate‐peroxidase cycle. In: Matis P, ed. Photosynthesis: from light to biosphere, Vol. II Dordrecht: Kluwer, 813–818. [Google Scholar]

- SharkeyTD, Vassey TL.1989. Low oxygen inhibition of photosynthesis is caused by inhibition of starch synthesis. Plant Physiology 90: 385–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SnedecorGW, Cochrane WG.1999. Statistical methods, 8th edn. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- StrzalkaK.1994. Effect of beta‐carotene on structural and dynamic properties of model phosphatidylcholine membranes. I. An EPR spin label study. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1194: 138–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SuzukiK, Ikawa T.1993. Oxygen enhancement of photosynthetic 14CO2 fixation in a freshwater diatom Nitzschia ruttneri Japan Journal of Phycology 41: 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- TsavalosAJ, Harker M, Young AJ.1993. Analysis of carotenoids using HPLC with diode‐array setection. Chromatography and Analysis April/May: 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- VavilinDV, Tyysttjärvi E, Aro E‐M.1995. In search of a reversible stage of photoinhibition in a higher plant: no changes in the amount of functional Photosystem II accompany relaxation of variable fluorescence after exposure of linkomycin‐treated Cucurbita pepo leaves to high light. Photosynthesis Research 45: 239–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VerhoevenAS, Adams III WW, Demmig‐Adams B.1996. Close relationship between the state of the xanthophyll cycle pigments and photosystem II efficiency during recovery from winter stress. Physiologia Plantarum 96: 567–576. [Google Scholar]

- VerhoevenAS, Demmig‐Adams B, Adams WW III.1997. Enhanced employment of the xanthophyll cycle and thermal energy dissipation in spinach exposed to high light and N stress. Plant Physiology 113: 817–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WieseC, Shi LB, Heber U.1998. Oxygen reduction in the Mehler reaction is insufficient to protect photosystems I and II of leaves against photoinactivation. Physiologia Plantarum 102: 437–446. [Google Scholar]

- Ziem‐HanckU, Heber U.1980. Oxygen requirement of CO2 assimilation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 591: 266–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.