Abstract

The current study examined between- and within-person processes related to friendship intimacy, close-friend substance use, negative affect, and self-medication. We tested between-person hypotheses that global negative affect, friendship intimacy, and close-friend drug use predict increased substance use, and the within-person hypothesis that friendship intimacy and close-friend substance use moderate the temporal relationship between daily negative affect and subsequent substance use (i.e., self-medication). Experience sampling methodology (ESM) was employed to capture daily variations in mood and substance use, and multilevel modeling techniques were used to parse between- versus within-person differences in risk for use. Findings supported between-person hypotheses that higher levels of negative affect and lower levels of friendship intimacy predicted greater substance use, and a consistent trend indicated that friendship intimacy and close-friend drug use interact to predict substance use more generally (though not for self-medication). Risk and protective mechanisms emerged from this interaction such that the effect of friendship intimacy on adolescent use depends on the degree of close-friend drug use. More specific reformulations of the risk processes involving friendships and self-medication among younger youth are indicated.

Keywords: adolescence, friendship, negative affect, quantitative methods, self-medication, substance use

Introduction

The self-medication hypothesis purports that individuals will use drugs as a direct means to minimize and regulate states of increased negative affect (Khantzian, 1997). Self-medication describes a within-person mechanism focusing on the negative reinforcement model of substance use whereby the use of drugs is a learned pattern of behavior motivated by the desire to alleviate negative mood in-the-moment. Whereas general “substance use” itself can be more broadly defined as the overall frequency or duration of use for a given individual, “self-medication” is defined for the same individual as the time-based sequential pairing of relative increases in negative affect followed by substance use (Khantzian, 2003). The pattern of emotion priming that defines self-medication is associated with particularly heavy and problematic alcohol use (Cooper, Russell, & George, 1988), and over time a risky cycle develops where negative affect and substance use ultimately impact one another bidirectionally (Baker, Piper, McCarthy, Majeskie, & Fiore, 2004). Self-medication is thus an important potential target for early intervention designed to reduce long-term risk for substance use disorders.

The substance use literature generally supports a strong association between increased negative affect and substance use, which reflects both within- and between-person processes. Self-medication is defined as a within-person process which indicates that when a given individual experiences elevations in negative affect relative to his/her own baseline, substance use may be used to cope (Khantzian, 2003; 1997). The concept of self-medication requires within-person temporal specificity, linking changes in affect and drug use within time. Between-person associations between affect and substance use, on the other hand, indicate that groups of individuals who report higher levels of negative affect also tend to be those who engage in higher levels of substance use more generally (e.g., Cooper, Frone, Russell, & Mudar, 1995). This between-person effect is evidenced, for example, in the high rates of comorbidity between negative affect disorders (e.g., depression) and substance use (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2009).

Findings supporting the self-medication hypothesis are consistently evidenced with adult and college-aged samples, showing that higher rates of substance use occur when individuals experience higher levels of negative affect relative to baseline (e.g., Hussong et al., 2001; Park, Armeli, & Tennen, 2004; Swendsen et al., 2000). Within-person negative affect-motivated substance use in adolescence is less extensively studied and the findings are more mixed, such that some have found evidence for self-medication while others have not (see Kassel et al., 2010, and Chassin, Ritter, Trim, & King, 2003, for reviews). Methodology offers one potential explanation for these inconsistent findings. Different methodologies are employed across studies, and few of these capture within-person daily variations in negative affect and substance use. As noted above, between-person measures of negative affect and substance use more generally do not capture the within-person daily fluctuations in affect and drug use which are required in order to test the self-medication hypothesis (Kassel et al., 2010). In between-person cross-sectional designs, the direction of effect cannot be determined and self-medication cannot be isolated from other potential mechanisms underlying the negative affect-use relationship (e.g., self-derogation theory; Kaplan, 1980). Longitudinal designs that capture changes in negative affect and use are more promising, but they typically use long time lags (e.g., months or years) that do not match onto predictions of self-medication (i.e., hours or days) (Chassin et al., 2003).

Research also indicates that some youth are more at risk for self-medication and may represent a particularly vulnerable subgroup of individuals (Cooper, Russell, Skinner, Frone, & Mudar, 1992), including those who evidence low levels of conduct problems (Hussong, Feagans Gould, & Hersh, 2008) or whose parents exhibit over-involved emotion socialization behaviors (Hersh & Hussong, 2009). Such subgroups may not be represented in all samples, yielding mixed results.

Despite some findings showing mixed results or no support for negative affect-motivated use in adolescence (Crooke, Reid, Kauer, McKenzie, Hearps, Khor, et al., 2013; see Kassel et al., 2010, and Chassin, Ritter, Trim, & King, 2003, for reviews), some empirical evidence supports that self-medication can emerge as early as adolescence (e.g., Gottfredson & Hussong, 2011; Gould, Hussong, & Hersh, 2012; Hersh & Hussong, 2009; Hussong et al., 2008; Reimuller, Shadur, & Hussong, 2011; Stice, Kirz, & Borbely, 2002). Moreover, adolescence is a period during which youth are more vulnerable to increases in negative affect, but developmentally lack the neurobiological systems to appropriately regulate these changes in affect, leading them to seek maladaptive coping methods including substance use (Steinberg et al., 2006). For some youth, self-medication becomes a way to self-regulate. Gaining a better understanding of which adolescents may be more likely to engage in self-medication will help to further resolve the inconsistent findings and will also help identify appropriate targets for prevention. In the current study, we assessed self-medication in adolescence through daily experience sampling data, and given that adolescent substance use is so intimately tied to one’s friendships (e.g., Ennett et al., 2006), we examined friendship intimacy as one potential vulnerability factor that may predict increased risk for self-medication.

Friendship Qualities and Adolescent Substance Use (between-person)

With an ultimate goal to understand how friendship qualities impact risk for adolescent self-medication (within-person), a helpful first step is to examine main effects that explain how the friendship context impacts risk for substance use more generally (between-person). One of the strongest indicators of adolescent behavior is that of their peers (Prinstein & Dodge, 2008), and as no exception, adolescent substance use is strongly associated with the friendship context (e.g., Ennett et al., 2006). Compared to abstaining teens, adolescents who drink or use drugs report being able to depend more on their friends, and report that their friends are more understanding and influential than their parents (Coombs, Paulson, & Richardson, 1991; Holden, Brown, & Mott, 1988). Research also shows that close friends (within dyads) and larger peer networks independently influence adolescent substance use (Urberg, Değirmencioğlu, & Pilgrim, 1997). In sum, there is clear support that substance use more generally is impacted by the context of friendships.

In previous research that examines between-person differences in risk for substance use based on particular friendship qualities, findings repeatedly show that both high and low levels of friendship intimacy and support (Hussong, 2000; Lifrak, McKay, Rostain, Alterman, & O’Brien, 1997; MacNeil, Kaufman, Dressler, & LeCroy, 1999; Wills & Vaughan, 1989; Wills et al., 2004) can predict youth’s drug use. Adolescents whose friendships involve both higher levels of positive and negative friendship qualities are more likely to use substances (Hussong, 2000), and greater hostility and less reciprocity within close friendship dyads predicts greater alcohol use (Windle, 1994).

Additional research examining between-person differences in drug use suggests that friendship intimacy has the potential to either increase or decrease risk for adolescent substance use, depending on other characteristics of the friend. Specifically, the relationship between the level of friendship intimacy and adolescent substance use is moderated by the level of the friends’ substance use. Indeed, one of the greatest risk factors for substance use is affiliation with drug-using peers (e.g., Ennett et al., 2006; Hussong, 2002) and high levels of support from such peer groups (Piko, 2000; Wills & Vaughan, 1989; Wills, 1990; Wills et al., 2004) and identified close friends (Urberg et al., 2005) further increase this risk, whereas high levels of support from close friends who do not use tend to minimize risk for use (Urberg et al., 2005). It has also been found that adolescents in close friendships with substance users that are characterized by fewer negative friendship qualities are at increased risk for substance use (Hussong & Hicks, 2003). Overall, these findings indicate a clear between-person effect indicating that friendship quality and friends’ drug use interact to predict adolescent substance use more generally. However, still left unexplored is the interaction between friendship quality and friends’ drug use in predicting within-person associations between daily variability in negative affect and the use of substances to cope (i.e., within the framework of self-medication). The contribution of the present study is to explore this question.

Friendship Intimacy, Friends’ Drug Use, and Self-Medication (within-person)

Among adults, self-medication is more effective in reducing negative affect when in the company of friends (Armeli et al., 2003). This suggests that friendships play a critical role in the use of substances to cope. It is unknown if the same pattern regarding friendships and self-medication emerges during adolescence. However, between-person effects show that adolescents who are in friendships characterized by lower levels of positive friendship qualities and higher friends’ substance use exhibit a stronger association between negative affect and substance use more generally (Hussong & Hicks, 2003). This between-person effect suggests that the interaction between friendship quality and friends’ drug use may also explain within-person processes among adolescents: the risk for self-medication.

Theoretically, the moderating effects of friendship intimacy and friends’ drug use on self-medication may reflect at least two different within-person mechanisms of risk. First, stress and coping models of substance use (Wills & Shiffman, 1985) suggest that in the context of lower levels of friendship intimacy and greater negative affect, adolescents seek alternative coping mechanisms, such as substance use. Additionally, adolescents’ overall risk for increased negative affect may be exacerbated if their friendships are characterized by less intimacy, a potentially stressful social experience for teens. Without adaptive strategies for minimizing negative affect (e.g., reliance on close friendships), self-medication may offer an effective alternative. Support for this notion comes from findings showing that college students with less intimate friendships were more likely to engage in substance use following days when they experienced higher levels of negative affect relative to baseline (Hussong et al., 2001). If less intimate friendship contexts also include drug using friends, then teens may be even more likely to self-medicate due to easy access and joint engagement in drug use. Though these questions have not yet been tested among younger adolescents, findings from Hussong et al. suggest that adolescents with lower levels of friendship intimacy and greater exposure to friends’ substance use may be more likely to use drugs particularly on days when they experience higher negative affect than usual (i.e., self-medication).

Social Learning Theory (Bandura, 1986) offers a second mechanism of risk for substance use. Such models of social influence suggest that for those in more intimate and supportive friendships with drug using peers, interactions with these friends may provide an environment that encourages drug use and is conducive to self-medication, particularly for adolescents who are prone to negative affect. Adolescents may be more likely to behave in ways similar to their friends when their friendships are more positively characterized. Indeed, the adverse effect that modeling by peers has on adolescents’ risk for substance use may be further strengthened in contexts of high levels of friendship support (Wills & Vaughan, 1989). Moreover, social learning of particular styles of use can also occur in these friendships; indeed, adolescents’ heavy drinking is in part associated not only with their own drinking motives but also with those of their peers (Hussong, 2003). Friends who use drugs may motivate, teach, and reinforce adolescents to self-medicate as a way of using substances. Thus, adolescents with high levels of friendship intimacy and with greater exposure to friends who use substances may also be more likely to self-medicate.

The Current Study

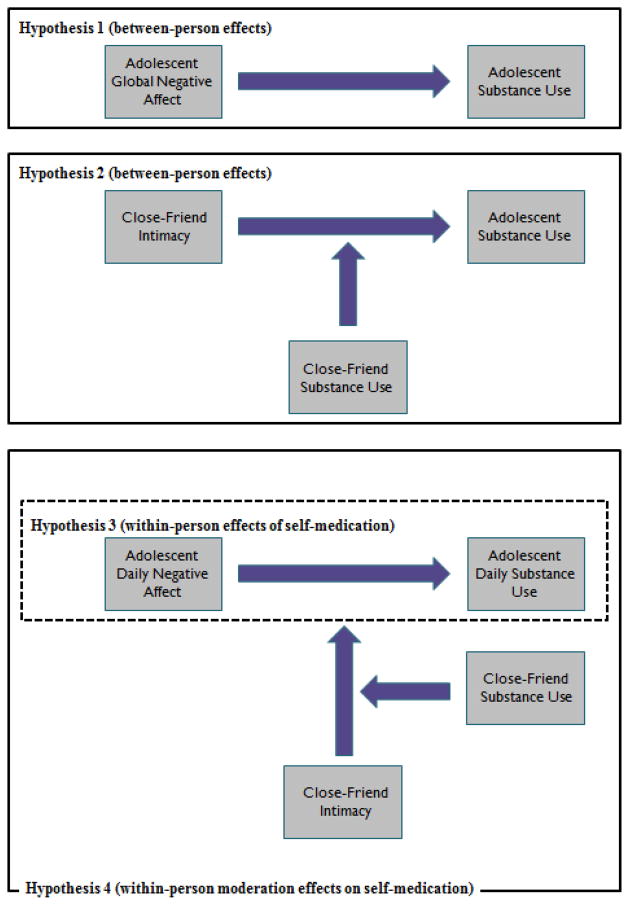

The current study examined both between- and within-person processes related to close-friend intimacy, close-friend substance use, negative affect, and adolescent substance use. Specifically, we tested the following set of hypotheses (see Figure 1): Hypothesis 1: Higher levels of global negative affect will predict increased substance use (between-person effects). Hypothesis 2: Adolescents will engage in more substance use generally if they have less intimate friendships or have intimate friendships with substance using close friends (between-person effects). Hypothesis 3: The self-medication hypothesis will be supported such that daily increases in negative affect will predict daily increases in substance use (within-person effects). Hypothesis 4: Close-friend intimacy and close-friend drug use will both moderate the relationship between within-person variability in daily negative affect and substance use (i.e., self-medication). Models of stress and coping and social learning indicate that adolescent self-medication may be moderated both by how much intimacy exists in these friendships and also who is delivering it (i.e., drug using versus non-drug-using close friends). Hypothesis 4 thus reflects two predictions: the within-person association between negative affect and substance use will be strongest for those in friendships with higher levels of intimacy and higher levels of close-friend substance use (reflecting social learning) and for those in friendships with lower levels of intimacy (regardless of close-friend substance use, reflecting stress and coping), as compared to others.

Figure 1.

Diagram indicating the four hypotheses.

Method

The goal of the current study was to use novel methodology and design to examine how friendship qualities impact adolescent self-medication during the transition period to high school. We employed experience sampling methodology (ESM) which involves measuring multiple in-vivo self-reports of participant experiences within a given day, and allows for measurement of within-person processes as well as individual differences in such processes (Bolger, Davis, & Rafaeli, 2003). Specifically, the use of a daily experience sampling design allows for examination of within-person variability in daily negative affect and substance use (in addition to between-person variability), which is critical for testing the self-medication hypothesis (Swendsen et al., 2000; Tennen, Affleck, Coyne, Larsen, & DeLongis, 2006). Thus, in the current study the theory of self-medication is matched to the appropriate methodology (i.e., daily experience sampling). These experience sampling procedures also capture affect and substance use patterns in real-world contexts and circumstances, which increases the external validity (Swendsen et al.).

Participants

Participants in the current study completed all study procedures in the spring of their eighth grade year (Phase I) and the summer before starting ninth grade (Phase II). In Phase I, 399 (out of 436 enrolled) eighth grade students from seven schools in a single county completed one-time school-based surveys. Thus, 92% of all eighth graders across the seven schools participated in Phase I. Valid data were provided by 365 students, determined by an honesty item assessing whether or not participants felt they were honest in their responses to the questionnaire. Participants in Phase I are 48% female, have a mean age of 13.55 years (SD= 0.61), and self-identify as 75% Caucasian, 18% African American, 2% Hispanic, 1% American Indian or Alaska Native, 1% Asian, and 4% Other.

Recruitment for Phase II began with rank-ordering the 365 participants based on a risk index that indicated any current substance use, any initiation of substance use by eighth grade, or affiliation with peers who had been involved in substance use prior to ninth grade. Participants were contacted by phone and screened in order of risk, such that the adolescents with the highest substance use risk indices were contacted first, yielding an elevated-risk sample. Of the original 365 with valid data, there were only 169 participants who indicated any level of risk for substance use. We attempted to contact these 169 participants, as well as 27 additional randomly selected participants who indicated no risk on this index but were included in our recruitment efforts in order to yield an initial recruitment list of 196 that was large enough to yield an adequate sample size. In order to be eligible, participants had to speak English with enough proficiency in order to complete consent procedures. Participants were not excluded based on gender, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status.

A total of 81 individuals completed the study (i.e., 41% of those targeted for recruitment, n = 196, or 57% of those who were both eligible and successfully contacted for recruitment, n = 142). Primary reasons for non-participation were inability to contact (n=33), ineligibility (n=21, language barrier, moving, did not pass grade, child death), limited availability (n=17), discomfort with the sampling paradigm (n=5), and privacy concerns (n=11). Twenty-eight individuals who did not participate provided no reason. The adolescents in Phase II are highly representative of the remaining original elevated-risk targets initially contacted for recruitment based on key variables of interest including adolescent and friends’ substance use, though participants in the current sample were more likely to be female and ethnic minority adolescents (see Hussong et al., 2008, for details). The current sample evidences greater risk than the Phase I school-based sample indicated by more frequent alcohol use, delinquency, and a greater number of friends who use substances, suggesting the successful recruitment of an elevated-risk sample.

To be eligible for analysis in the current study, participants had to complete the assessment involving the experience sampling methodology (ESM). Of the original 81 from Phase II, two participants did not complete the ESM procedures and six were missing more than 16 of the 21 days of ESM data and were not included in the analyses. Thus, the final sample includes 73 target adolescents from Phase II, with a total of 1406 observations of both daily negative affect and substance use scores1. Of the 73 participants, only 57 had complete data on all variables for analysis, and thus any missing values were imputed using multiple imputation techniques (Rässler, Rubin, & Schenker, 2008). The 73 participants are 53% female, have a mean age of 13.92 years (SD=0.47), and self-identify as 56% Caucasian, 19% African American, 3% Hispanic, 1.5% American Indian or Alaska Native, 1.5% Asian, and 19% Other.

Procedure

In the summer between eighth and ninth grade, students completed in-home assessments during both an initial and final session (three weeks apart) and completed an experience sampling procedure during the three weeks between sessions. During the initial session, students completed computer-administered interviews and received instructions and materials for the experience sampling procedure (i.e., a wristwatch, a daily recording device and booklets, and a security box). Adolescents were asked to provide the names and contact information for their top three closest friends so that staff could contact them to participate in the final session of the study (three weeks later). Study staff attempted to contact each adolescent’s top three friends in order of rated closeness. Thus, the friends who participated in the study were identified as one of three top close friends, but may not have been the identified closest friend. Additionally, because the three close friends were identified by target-adolescent-report (and not by friend-report), the friendship dyads are not necessarily comprised of reciprocal best friends. During the final session, the adolescent’s close friend completed paper-and-pencil interviews and adolescents completed computer-administered interviews.

The experience sampling procedure occurred during the 21 days in between the initial and final sessions. Target adolescents were asked to complete brief surveys (1–2 minutes) in response to a pre-programmed wristwatch alarm. Each day, three pre-set alarms prompted participants to rate their levels of negative affect (sad, mad, worried, and stressed) at the moment that the alarm sounded. Reports of daily negative affect were recorded by using a small pad of pre-labeled paper and a pen that were both kept securely in an unobtrusive plastic container that was attached to the wristwatch. A fourth and final daily alarm prompted adolescents to record their substance use (alcohol, marijuana, and other illicit drugs) for the entire day. In order to protect participant confidentiality, the substance use recordings were kept in a security box in the adolescent’s home. These sensitive response codes were purposefully meant to be cryptic to protect participants’ reports of substance use. 2Precautions were taken to help ensure the privacy and confidentiality of all daily recordings and phone messages, including the use of response codes that were not interpretable to anyone outside of the study. Additional precautions were taken to further prevent the disclosure of personal information, which included acquiring a Certificate of Confidentiality.

Measures

All assessments for this analysis were completed during the initial and final sessions and during the three-week experience sampling period during Phase II. All measures yielded manifest variables.

Demographics

During the initial session, adolescents self-reported gender, age, and ethnicity, and parents self-reported their highest level of education. The highest level of education obtained between both parents was used to indicate parent education. The majority of parents (63%) had either partially or fully completed college or technical/vocational school. During the final session, adolescents’ close friends self-reported gender, age, and ethnicity.

Close-friend-report of substance use (final session)

The close-friend substance use scale consisted of five items from Chassin, Rogosch, and Barrera (1991) that were adapted to capture close friends’ self-reports of drug use in the past three months. Similar adaptation of these items has been found to have good reliability in previous studies (Hussong, 2000; Hussong & Hicks, 2003). The five items included frequency of alcohol, marijuana, and other illicit drug use, frequency of heavy alcohol use (5 or more drinks at one time), and frequency of being drunk. For reports of alcohol use, frequency item responses ranged from (0) not at all to (7) everyday; frequency item responses for number of times drunk, heavy alcohol use, marijuana use, and use of other drugs, ranged from (0) not at all to (4) once a week. The scale for close-friend substance use was constructed by first standardizing all items and then calculating the mean score across all items (M=0.004, SD=0.74, α = .80).

Adolescent daily substance use (ESM)

The experience sampling of substance use involved adolescents recording their daily use of alcohol, marijuana, and other illicit substances each day for 21 days. Nightly recordings of drug use were completed at 10:00 pm in response to the final pre-set alarm, or before going to bed if after 10:00 pm. Alcohol use was rated on a 6-point scale from 0 to 5 or more standard drinks of alcohol per day. In order to protect reports of alcohol use, recordings were made by using numbers (0–5). Responses for marijuana and other illicit drug use were endorsed as either “yes” or “no.” Items were taken directly from Hussong et al. (2001). The outcome measure for overall daily substance use was dichotomized to represent any use versus no use. During the 21-day experience sampling period, 24.7% of all participants endorsed using alcohol, 9.6% endorsed using marijuana, and 5.5% endorsed using any illicit drug other than marijuana.

Adolescent daily negative affect (ESM)

Variation in negative affect was assessed through the experience sampling of daily mood across the three-week period. Adolescents reported the degree to which they felt sad, mad, worried, and stressed when prompted by three daily random pre-set alarms. For each of the four types of negative affect, item responses ranged from (1) not at all to (5) very much, indicating the degree to which adolescents endorsed feeling each emotion at that moment. Items reflecting negative affect were chosen based on the dimensions that are often used in self-medication research (e.g., Hussong et al., 2001). The descriptions of the four types of negative affect were adapted from the Multiple Affect Adjective Check List – Revised (MAACL-R; Lubin et al., 1986) in order to use age-appropriate wording. To create a daily negative affect composite score for each of the 21 days, the maximum ratings given to each type of emotion (sad, mad, worried, and stressed) were averaged together within any given day. In previous research, reports of daily negative affect were found to be adequately reliable (average α = .79; Hussong et al., 2008). Results from the current sample yielded a mean global negative affect score of 1.83 (SD=0.69) with scores ranging from 1.00 to 3.5; alphas for the daily negative affect measures ranged from .70 to .91 with an average alpha of .82. Although results from the current sample indicated that our adaptation of the MAACL-R was adequately reliable, a notable limitation is that we did not establish psychometric properties of the adapted version prior to including it in the current study.

Close-friend and adolescent reports of friendship intimacy (final session)

Both the target adolescent and his/her close friend independently reported on the positive qualities of their shared friendship in regards to the previous three weeks. Four subscales from the Network of Relationships Inventory (NRI, Furman & Buhrmester, 1985), including three items each for loyalty, self-disclosure, affection, and companionship, were used to assess close-friend intimacy. The loyalty subscale was supplemented with an additional item in order to capture a broader dimension of loyalty, and the affection subscale was supplemented with an additional item in order to assess reciprocation within the friendship (Barrera, Chassin, and Rogosch, 1993), yielding a total of 14 items. The item responses ranged from (1) little to none to (5) the most possible. Correlations across the four subscales from the NRI were large and highly significant (p<.0001) ranging from r = 0.61–0.79 and r = 0.53–0.79 for target- and close-friend report, respectively. Additionally, one-factor confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were conducted using Maximum Likelihood estimation in MPlus version 5.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998) to evaluate the extent to which all 14 intimacy items load onto one factor. CFA results yielded acceptable model fit and large factor loadings for all items onto one intimacy factor, with factor loadings ranging from .54 to .89 and .64 to .83 for target- and close-friend report, respectively. Thus, all NRI item responses were averaged and the mean score across all subscales represents an overall score for close-friend intimacy, separately for each reporter (for target-report M=3.57, SD=0.89, and α = .94; for close-friend-report M=3.61, SD=0.88, and α = .94). We retained close-friend- and target-report as separate indicators of intimacy because these adolescent dyads were not necessarily reciprocal best friends, and although the correlation between reporters is large (r = 0.47, p <.001), it does indicate that there are some differences in perspective with respect to how both adolescents viewed their shared friendship.

Results

Missing Data Analysis

The analysis sample consists of 73 target adolescents, however only 57 had complete data on all between-person variables for analysis. Of the individuals who had incomplete data for any of the key predictors of interest, two were missing on target-report of intimacy, sixteen were missing on close-friend report of intimacy, and fifteen were missing on close-friend substance use. Initial attrition analyses were conducted in order to determine if target adolescents with missing close-friend-reports of key predictor variables differed significantly from those who had complete data. A series of t-tests showed that there were no significant differences across key variables, including target-report of close-friend intimacy, target-report of substance use in the general peer network, and target self-report of substance use. These findings suggest that missingness in these data is not related to key variables of interest, and values are likely missing at random. Thus, we used multiple imputation to perform missing data analyses following Rässler, Rubin, and Schenker (2008). Predictors in the multiple imputation analysis included control variables, close-friend-reports of substance use, both close-friend and target reports of intimacy, target reports of daily mood and substance use, and target reports of substance use in their general peer network. Thirty imputed data sets were generated using SAS PROC MI (SAS Institute, 2009), consistent with recommendations indicating that more than 20 imputed data sets are necessary to maximize power and reliability of the estimates and to minimize the standard errors of the estimates (Graham, Olchowski, & Gilreath, 2007). Results of subsequent data analysis of the 30 data sets were combined using SAS PROC MI ANALYZE (SAS Institute).

Primary Analyses

Multilevel models can parse between- and within-person variability, which is necessary in order to test the self-medication hypothesis. This analysis focused on the moderating influences of close-friend intimacy and close-friend substance use on self-medication, and involved a three-way cross-level interaction between a within-subjects factor (daily negative affect) and two between-subjects factors (close-friend intimacy and close-friend substance use) to predict the likelihood of an adolescent’s substance use. Although these analyses are quite demanding given the modest sample size, significant interaction effects have been found in previous analyses with the current sample (Feagans Gould, Hersh, & Hussong, 2007; Hersh & Hussong, 2009; Hussong et al., 2008; Reimuller, Shadur, & Hussong, 2011), indicating that it is indeed possible to find such an effect.

Between-person (level 2) predictors of substance use intercepts included control variables (i.e., adolescent gender, parent education, and adolescent ethnicity) and the main effects for the global negative affect index, close-friend intimacy, and close-friend substance use. Within-person (level 1) predictors included whether ESM data were collected on a weekend or weekday (to control for variation of substance use based on time of the week) and daily negative affect ratings. Thus, repeated measures were nested within person. Two- and three-way interactions between daily negative affect, close-friend intimacy, and close-friend substance use were added to the model to test study hypotheses. All continuous between-person predictors were grand-mean centered, and the daily within-person negative mood predictor was person-centered. The random effect of the model intercept and the fixed effect for the slope for daily effect of negative affect on substance use were estimated as well.

We used a non-linear multilevel modeling approach to test study hypotheses following established guidelines for distinguishing within- (i.e., self-medication) and between-person effects (Bryk & Raudenbush, 1987). Due to our dichotomous outcome measure, we estimated these models using maximum likelihood with nine points of quadrature in PROC Glimmix (SAS Institute, 2009). Maximum likelihood estimation yields efficient parameter estimates and also is preferred in cases where the regression coefficients are of particular interest (Schwartz & Stone, 1998). Nine points of quadrature were used in order to increase the chances for successful model convergence.

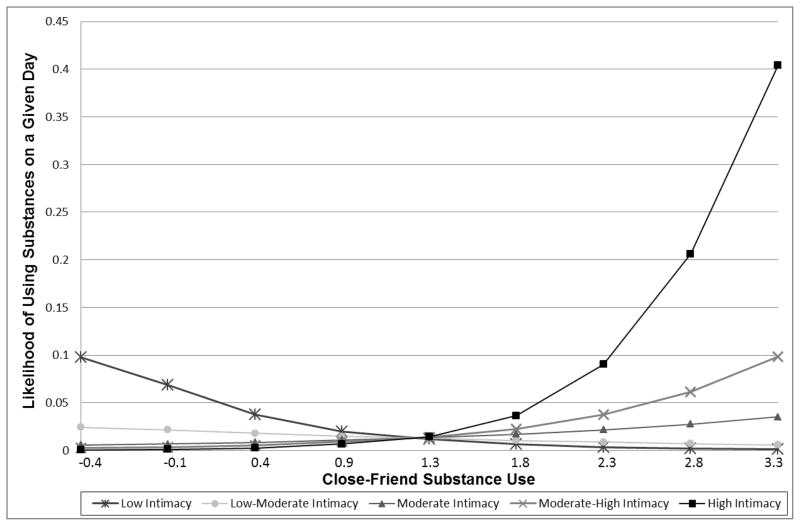

The multilevel model was estimated twice, once for target-report (model 1) and once for close-friend-report (model 2) of close-friend intimacy. In support of Hypothesis 1, results show a strong and consistent between-person main effect of global negative affect on substance use in both model 1 (β = 1.54, OR = 4.66, p < .01) and model 2 (β = 1.66, OR = 5.26, p < .01; see Table 1). In support of Hypothesis 2, there was a marginally significant two-way interaction between close-friend substance use and close-friend intimacy predicting adolescent substance use (model 1 target-report; β =.82, OR = 2.27, p <.10). We probed the interaction by plotting predicted values for daily adolescent substance use as a function of close-friend substance use at varying levels of close-friend intimacy to characterize the family of curves (Curran, Bauer, & Willoughby, 2006). Probing of this between-person interaction indicated two trends for increased risk: 1) increasing levels of close-friend substance use predicted adolescent substance use more strongly for those who also have high levels of close-friend intimacy compared to those with low levels of close-friend intimacy (consistent with social learning theory), and 2) at low levels of close-friend substance use, adolescents with the lowest levels of close-friend intimacy are also more likely to use substances compared to those with high levels of close-friend intimacy (consistent with the stress and coping model; see Figure 2). The probed between-person interaction also shows a buffering effect such that the lowest risk for substance use occurs in the context of low levels of close-friend substance use and high intimacy (see Figure 2).

Table 1.

Results of Mixed Models Testing Close-Friend Intimacy and Close-Friend Substance Use Effects on Self-Medication

| PREDICTORS | Close-Friend Intimacy (Target-report) | Close-Friend Intimacy (Close-friend-report) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

| β | OR | β | OR | |

|

| ||||

| Between-Person | ||||

|

| ||||

| Gender | −0.25 | .78 | 0.23 | 1.26 |

|

| ||||

| Race | 0.98 | 2.66 | 0.95 | 2.59 |

|

| ||||

| Parent Education | 0.54 | 1.72 | 0.59 | 1.80 |

|

| ||||

| Global Negative Affect | 1.54** | 4.66 | 1.66** | 5.26 |

|

| ||||

| Close-Friend Substance Use | 0.76 | 2.14 | 0.52 | 1.68 |

|

| ||||

| Close-Friend Intimacy | −1.11** | .33 | −0.26 | .77 |

|

| ||||

| Within-Person | ||||

|

| ||||

| Weekday | −0.09 | .91 | −0.09 | .91 |

|

| ||||

| Daily Negative Affect | −0.07 | .93 | 0.01 | 1.01 |

|

| ||||

| Cross-level Interactions | ||||

|

| ||||

| Close-Friend Substance Use x Close-Friend Intimacy | 0.82+ | 2.27 | 0.45 | 1.57 |

|

| ||||

| Close-Friend Substance Use x Daily Negative Affect | −0.17 | .84 | −0.32 | .73 |

|

| ||||

| Close-Friend Intimacy x Daily Negative Affect | −0.18 | .84 | −0.003 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||

| Close-Friend Substance Use x Close-Friend Intimacy x Daily Negative Affect | −0.08 | .92 | 0.04 | 1.04 |

Note. Reported values are unstandardized betas. Significance levels are indicated by + (for p <.10) and

(for p <.01). OR = odds ratio.

Figure 2.

Marginally significant two-way interaction between close-friend substance use and target-report of close-friend intimacy. Plotting of this interaction indicates a trend for increasing levels of close-friend substance use to predict adolescent substance use more strongly for those who also have high levels of close-friend intimacy. Close-friend substance use values are grand-mean centered.

Additionally, the between-person main effect of close-friend intimacy was significant in model 1 (target-report; β = −1.11, OR = .33, p < .01; but not in model 2 close-friend-report: β = −0.26, OR = .77, p > .05), showing that adolescents who reported lower levels of close-friend intimacy are more likely to use substances. However, the between-person main effect of close-friend substance use on target substance use did not reach significance in either model 1 (β = 0.76, OR = 2.14, p > .05) or model 2 (β = 0.52, OR = 1.68, p > .05).

Results did not support the self-medication hypothesis (Hypothesis 3): the within-person effect of daily negative affect on subsequent substance use was not significant across both model 1 (β = −0.07, OR = 0.93, p > .05) and model 2 (β = 0.01, OR = 1.01, p > .05). Results also did not support Hypothesis 4: the cross-level three-way interaction between close-friend substance use, close-friend intimacy, and daily negative affect in predicting daily substance use was not significant across model 1 (β = −0.08, OR = .92, p > .05) or model 2 (β = 0.04, OR = 1.04, p > .05).

Discussion

The current study examined whether close-friend substance use and close-friend intimacy predict risk for self-medication among adolescents (within-person effects) as well as main effects and interactions between global negative affect, close-friend intimacy, and close-friend substance use in predicting adolescent drug use more generally (between-person effects). There was clear support for the between-person effects showing that increased global negative affect and lower levels of target-reported close-friend intimacy predicted higher levels of substance use more generally. Findings also provided some support for the interaction between close-friend intimacy and close-friend substance use in predicting daily adolescent substance use. However, the self-medication hypothesis was not supported in the current study. Potential explanations and interpretations of these findings are discussed further.

Close-Friend Intimacy, Close-Friend Substance Use, and Daily Substance Use

Findings supported our hypothesis that adolescents will engage in more substance use if they have less intimate friendships or have intimate friendships with substance using friends, reflecting between-person effects. The marginally significant interaction between close-friend substance use and close-friend intimacy indicates that the two proposed mechanisms (i.e., social learning, stress and coping) may underlie risk for substance use more generally, though not specifically for self-medication. This interaction shows a trend for the positive association between close-friend substance use and adolescent daily use to be strongest for target adolescents who report high levels of close-friend intimacy, reflecting the social learning model. The stress and coping model is also indicated in this interaction such that even at low levels of close-friend substance use, adolescents with the lowest levels of close-friend intimacy are at increased risk for use. Finally, a buffering effect can be seen in the interaction as well, showing that the lowest risk for substance use appears to be the combination of low levels of close-friend substance use and high intimacy. Thus, the one interaction effect and the subsequent main effects indicate a consistent trend for the effect of intimacy and close-friend substance use on adolescent daily use, such that close-friend intimacy may be either protective or risky depending on the degree of close-friend substance use.

Although these patterns are consistent with the two different risk mechanisms, the interaction is only marginally significant and thus further exploration of this relationship within the context of ESM data is certainly needed. This interaction effect is consistent with other studies finding that friends’ use predicts adolescent use most strongly for those with fewer negative friendship qualities (Hussong & Hicks, 2003) and greater social support (e.g., Piko, 2000; Wills & Vaughn, 1989; Wills, 1990; Wills et al., 2004; Urberg et al., 2005), as well as findings showing that high levels of support from non-using friends minimizes risk for use (Urberg et al.), though these studies used either cross-sectional or short-term longitudinal designs and not ESM techniques.

The Close Friendship Context and Self-Medication

There are four potential explanations for why the self-medication hypothesis (Hypothesis 3) and the proposed within-person interaction between daily negative affect, close-friend intimacy, and close-friend drug use in predicting daily drug use (Hypothesis 4) were not supported in the current study. First, friendship-based risk processes for self-medication may be more complex than what is captured by the current study, and omitted variables may have resulted in non-significant findings. For example, there could be a gender effect such that close-friend substance use and close-friend intimacy predict self-medication only for girls. Research has shown that girls more than boys endorse greater levels of intimacy, enhancement of worth from their friendships, and affection with their friends, and report depending more on their close friends (Furman & Buhrmester, 1985). Moreover, middle school girls report that friendships offer significantly more intimacy compared to all other relationships, whereas boys do not report such differences, indicating that intimacy with close friends becomes increasingly important for girls (Buhrmester & Furman, 1987). With friendships holding such value and import for girls, those who struggle to maintain intimate friendships may be at greater risk both for increased levels of negative affect and subsequently for self-medication. Females may also be more prone to risk processes involving social learning and joint engagement in drug use, as increased levels of support from friends has been shown to predict substance use more strongly in girls than in boys (Wills & Vaughan, 1989). In the current study it was not feasible to explore a gender effect due to the modest sample size; however, this is an important area for further exploration.

Second, because the proposed risk mechanism for self-medication was not supported among younger youth, but others have found that lower levels of friendship intimacy predicts self-medication in young adults (Hussong et al., 2001), it is possible that alternative components of the friendship context play a role in predicting negative affect-motivated use among these younger teens. In other words, the close friendship context may operate independently from intimacy and close-friend substance use levels in predicting this particular style of drug use among adolescents. To speculate, components of the friendship context that may predict self-medication for younger youth might include close relationships with older teens, the prevalence of affective disorders among friends (e.g., depression, anxiety), or exposure to other types of deviant peer behavior (e.g., friends’ conduct problems), rather than the interaction between intimacy and close-friend drug use which may be a better predictor of self-medication among older youth.

Third, the adolescent close friendship context may not be related to self-medication for this younger age group – rather, there may simply be other mechanisms that moderate the relation between negative affect and substance use for adolescent youth. Although cross-sectional designs show that close-friend substance use and friendship intimacy impact substance use more generally (and there is support for this in the current study), the friendship context may be less critical in predicting risk for self-medication among younger adolescents. Thus, contrary to ESM research findings with adult samples suggesting that the social context matters in predicting self-medication as a coping method (e.g., Armeli et al., 2003; Hussong et al., 2001), the same mechanism may not apply to younger age groups. Other factors and mechanisms may be more appropriate predictors of self-medication for such youth. For example, in the current data set, greater parental social support (Reimuller, Shadur, & Hussong, 2011) and poorer parent emotion socialization (Hersh & Hussong, 2009) predicted increased risk for self-medication among adolescents. It may be that compared to close friends’ influences, parental support and influence during this developmental period are ultimately stronger predictors for self-medication, which reflects a more problematic style of use, as opposed to drug use more generally. Thus, both risk for and protection against negative affect-motivated substance use among younger adolescents may be best indicated by specific characteristics of the parent-child relationship.

Fourth, consistent with between-person effects in the current study, we might expect that more chronically high levels of adolescent negative affect may be more predictive of increased substance use rather than the hypothesized short-term temporal relations between affect and substance use (as in self-medication). In other research employing experience sampling methodology, adolescents’ emotional experiences within a given day are significantly more extreme, volatile, and rapidly changing in valence compared to adults (Larson & Maryse, 1994). Thus, within-person short-term associations between mood and substance use may be weaker among adolescents given the frequent fluctuations of extreme moods within any given day, combined with limited access to drugs or alcohol, as compared to adults.

Nonetheless, self-medication research supports the idea that a subgroup of teens may be most at risk for this style of use, increasing the need for better identification of the individuals who are at heightened risk for self-medication (Chassin et al., 2003; Hussong et al., 2001). The current findings preliminarily rule out one potential contextual factor (the close friendship context) that does not seem to predict such risk. This argument is made cautiously given that the sample size is relatively small, and this study was the first to test the moderating effect of the close friendship context on self-medication in teens; thus findings are considered preliminary. Nonetheless, significant effects of multiple varying moderators on self-medication have been found in previous analyses with the current sample, as noted above (Feagans Gould, Hersh, & Hussong, 2007; Gottfredson & Hussong, 2011; Hersh & Hussong, 2009; Hussong et al., 2008; Reimuller, Shadur, & Hussong, 2011), offering support for the notion that power alone cannot explain the lack of significant findings in the current study.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of the current study include the use of experience sampling methods to capture daily variations in mood and substance use as an index of self-medication, and the use of multiple reporters of close-friend intimacy. The sample is relatively diverse, and the majority of experience sampling studies to date have been employed with mostly Caucasian adult samples (e.g., Armeli et al., 2003; Cleveland & Harris, 2010; Swendsen et al., 2000). Moreover, this study is the first to test multiple mechanisms of risk related to the close friendship context as moderators of self-medication among youth.

There are several limitations of the current study that must be noted. First, quantitative methods do not currently include power calculations for multilevel models with binary outcomes that include interactions, but given the modest sample size of 73, power to detect interactions may still be limited. Nonetheless, we found significant effects with these data in several other sets of analyses.

Second, the low base rate of daily substance use in the current sample limits the extent to which the proposed mechanisms can be tested, given that only 77 of 1411 observations of drug use were endorsed positively, and only 20 of 73 adolescents reported any use during the 21-day experience sampling period. Although the overall rates of use are low, it is important to note that we selected an elevated risk sample, and thus the current findings may not generalize to the broader population given that rates of use would be even lower.

Third, the self-report measure of close-friend intimacy may limit the extent to which closeness and supportive behaviors within dyads are truly captured. An observational measure of intimacy would allow greater insight into enacted friendship behaviors, and future studies should consider employing such alternative methods of measuring the friendship intimacy construct.

Implications and Conclusions

The current study employed experience sampling methodology and multilevel modeling techniques to assess between-person and within-person differences in risk for substance use. Between-person effects suggest that adolescents who have higher mean levels of negative affect and lower levels of close-friend intimacy are at greatest risk for substance use. The interaction between close-friend substance use and close-friend intimacy highlights a trend suggesting that close friendships may serve to either buffer or increase risk for general substance use, depending on the degree of close-friends’ use. These findings indicate that interventions focused on minimizing the experience of negative affect for youth as well as facilitating close friendships with non-using peers may help minimize risk for substance use more generally.

However, findings do not indicate which individuals are at risk for self-medication, as the close friendship context did not moderate the within-person relation between daily variations in negative affect and substance use. The findings indicate that the proposed mechanisms involving intimacy and close-friends’ substance use do not explain why individuals may be at increased risk for this particularly problematic style of use. Thus, the results encourage greater exploration of other factors that help to further identify vulnerable subgroups who may be more likely to use self-medication as a way to cope. An additional direction for future research includes further exploration of alternative within-person affective-based processes (i.e., other than self-medication) that may help explain why between-person differences in friendship intimacy predict risk for substance use.

Footnotes

In most cases, the adolescents participated only once as either a target or as a close friend. There were sixteen adolescents who participated twice, once as a target and once as a friend. Of those, there were eight (or four friendship dyads) who participated once as target and once as a friend for one another. Eight other adolescents participated once as a target and once as a friend for other targets who themselves were not reciprocally chosen as friends. One of these adolescents participated three times, once as a target and also as a friend for two other targets.

As a back-up source of data collection of daily reports, and to minimize data loss, all participants were asked to also place a phone call into the study office phone to leave a message with their daily recordings (three assessments of mood, one substance use assessment). In the sample of N=79 who completed the experience sampling procedure, 46% of the observations were reported in these two forms (daily in-vivo recordings and the corresponding data phoned in by participants), and of those data available from both sources, 99% of the observations overlapped perfectly.

References

- Armeli S, Tennen H, Todd M, Carney MA, Mohr C, Affleck G, et al. A daily process examination of the stress-response dampening effects of alcohol consumption. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17(4):266–276. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.4.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR, Fiore MC. Addiction motivation reformulated: An affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychological Review. 2004;111(1):33–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ US: Prentice-Hall, Inc; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Chassin L, Rogosch F. Effects of social support and conflict on adolescent children of alcoholic and nonalcoholic fathers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;64(4):602–612. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.64.4.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Davis A, Rafaeli E. Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annual Review of Psychology. 2003;54:579–616. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW. Application of hierarchical linear models to assessing change. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;101:147–158. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.101.1.147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D, Furman W. The development of companionship and intimacy. Child Development. 1987;58(4):1101–1113. doi: 10.2307/1130550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Ritter J, Trim RS, King KM. Adolescent substance use disorders. In: Mash EJ, Barkley RA, editors. Child Psychopathology. 2. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2003. pp. 199–230. [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Rogosch F, Barrera M. Substance use and symptomotology among adolescent children of alcoholics. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:449–463. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland HH, Harris KS. The role of coping in moderating within-day associations between negative triggers and substance use cravings: A daily diary investigation. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35(1):60–63. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombs RH, Paulson MJ, Richardson MA. Peer vs. parental influence in substance use among Hispanic and Anglo children and adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1991;20(1):73–88. doi: 10.1007/BF01537352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:990–1005. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Russell M, George WH. Coping, expectancies, and alcohol abuse: A test of social learning formulations. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97(2):218–230. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.97.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Russell M, Skinner JB, Frone MR, Mudar P. Stress and alcohol use: Moderating effects of gender, coping, and alcohol expectancies. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1992;101(1):139–152. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.101.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooke AHD, Reid SC, Kauer SD, McKenzie DP, Hearps SJC, Khor AS, et al. Temporal mood changes associated with different levels of adolescent drinking: Using mobile phones and experience sampling methods to explore motivations for adolescent alcohol use. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2013;32(3):262–268. doi: 10.1111/dar.12034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Bauer DJ, Willoughby MT. Testing and probing interactions in hierarchical linear growth models. In: Bergeman CS, editor. Methodological issues in aging research. Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2006. pp. 99–129. [Google Scholar]

- Ennett ST, Bauman KE, Hussong AM, Faris R, Foshee VA, Cai L, et al. The peer context of adolescent substance use: Findings from social network analysis. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16(2):159–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2006.00127.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feagans Gould L, Hersh MA, Hussong AM. Self-medication in adolescence: Examining sub-populations at risk. Poster presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development; Boston, MA. 2007. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Children’s perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology. 1985;21(6):1016–1024. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.21.6.1016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson NC, Hussong AM. Parental involvement protects against self- medication behaviors during the high school transition. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(12):1246–1252. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould LF, Hussong AM, Hersh MA. Emotional distress may increase risk for self-medication and lower risk for mood-related drinking consequences in adolescents. The International Journal of Emotional Education. 2012;4(1):6–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Olchowski AE, Gilreath TD. How many imputations are really needed? Some practical clarifications of multiple imputation theory. Prevention Science. 2007;8:206–213. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersh MA, Hussong AM. The association between observed parental emotion socialization and adolescent self-medication. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology: An Official Publication of the International Society for Research in Child and Adolescent Psychopathology. 2009;37(4):493–506. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9291-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden MG, Brown SA, Mott MA. Social support network of adolescents: Relation to alcohol abuse. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1988;14(4):487–498. doi: 10.3109/00952998809001566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM. Perceived peer context and adolescent adjustment. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2000;10(4):391–415. doi: 10.1207/SJRA1004_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM. Differentiating peer contexts and risk for adolescent substance use. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2002;13(3):207–220. doi: 10.1023/A:1015085203097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM. Social influences in motivated drinking among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17(2):142–150. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Hicks RE. Affect and peer context interactively impact adolescent substance use. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31(4):413–426. doi: 10.1023/A:1023843618887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Feagans Gould L, Hersh MA. Conduct problems moderate self-medication and mood-related drinking consequences in adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69(2):296–307. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.296. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Hicks RE. Affect and peer context interactively impact adolescent substance use. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31(4):413–426. doi: 10.1023/A:1023843618887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Hicks RE, Levy SA, Curran PJ. Specifying the relations between affect and heavy alcohol use among young adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110(3):449–461. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.110.3.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan HB. Deviant behavior in defense of self. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Kassel JD, Hussong AM, Wardle MC, Veilleux JC, Heinz A, Greenstein JE, et al. Affective influences in drug use etiology. In: Scheier LM, editor. Handbook of drug use etiology: Theory, methods, and empirical findings. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 2010. pp. 183–205. [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: A reconsideration and recent applications. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 1997;4(5):231–244. doi: 10.3109/10673229709030550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ. Understanding addictive vulnerability: An evolving psychodynamic perspective. Neuro-Psychoanalysis. 2003;5(1):5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Larson RW, Maryse RH. Family emotions: Do young adolescents and their parents experience the same states? Journal of Research on Adolescence, Special issue: Affective processes in adolescence. 1994;4(4):567–583. [Google Scholar]

- Lifrak PD, McKay JR, Rostain A, Alterman AI, O’Brien CP. Relationship of perceived competencies, perceived social support, and gender to substance use in adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(7):933–940. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubin B, Zuckerman M, Hanson PG, Armstrong T, Rinck CM, Seever M. Reliability and validity of the Multiple Affect Adjective Check List- Revised. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 1986;8(2):103–117. doi: 10.1007/BF00963575. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacNeil G, Kaufman AV, Dressler WW, LeCroy GW. Psychosocial moderators of substance use among middle school-aged adolescents. Journal of Drug Education. 1999;29(1):25–39. doi: 10.2190/49R9-08GD-ECUH-DXAE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Armeli S, Tennen H. The daily stress and coping process and alcohol use among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65(1):126–135. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piko B. Perceived social support from parents and peers: Which is the stronger predictor of adolescent substance use? Substance Use & Misuse. 2000;35(4):617–630. doi: 10.3109/10826080009147475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Dodge KA. Current issues in peer influence research. In: Prinstein MJ, Dodge KA, editors. Understanding peer influence in children and adolescents. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Rässler S, Rubin DB, Schenker N. Incomplete data: Diagnosis, imputation, and estimation. In: de Leeuw ED, Hox JJ, Dillman DA, editors. International handbook of survey methodology. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Group/Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2008. pp. 370–386. [Google Scholar]

- Reimuller AN, Shadur J, Hussong AM. Parental social support as a moderator of self-medication in adolescents. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(3):203–208. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS documentation, Version 9.2. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz JE, Stone AA. Strategies for analyzing ecological momentary assessment data. Health Psychology. 1998;17(1):6–16. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Dahl R, Keating D, Kupfer DJ, Masten AS, Pine DS. The study of developmental psychopathology in adolescence: Integrating affective neuroscience with the study of context. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology, vol 2: Developmental neuroscience. 2. Hoboken, NJ US: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2006. pp. 710–741. [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Kirz J, Borbely C. Disentangling adolescent substance use and problem use within a clinical sample. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2002;17(2):122–142. doi: 10.1177/0743558402172002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Rockville, MD: 2009. Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-36, HHS Publication No. SMA 09-4434. [Google Scholar]

- Swendsen JD, Tennen H, Carney MA, Affleck G, Willard A, Hromi A. Mood and alcohol consumption: An experience sampling test of the self-medication hypothesis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109(2):198–204. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.109.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennen H, Affleck G, Coyne JC, Larsen RJ, DeLongis A. Paper and plastic in daily diary research: Comment on Green, Rafaeli, Bolger, Shrout, and Reis (2006) Psychological Methods. 2006;11(1):112–118. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.11.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urberg KA, Değirmencioğlu SM, Pilgrim C. Close friend and group influence on adolescent cigarette smoking and alcohol use. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33(5):834–844. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.33.5.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urberg K, Goldstein MS, Toro PA. Supportive relationships as a moderator of the effects of parent and peer drinking on adolescent drinking. Journal of Research on Adolescents. 2005;15(1):1–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2005.00084.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA. Multiple networks and substance use. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology. 1990;9(1):78–90. [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Resko JA, Ainette MG, Mendoza D. Role of parental support and peer support in adolescent substance use: A test of mediated effects. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18(2):122–134. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.2.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Shiffman S. Coping and substance use: A conceptual framework. In: Shiffman S, Wills TA, editors. Coping and substance use. New York: Academic Press; 1985. pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Vaughan R. Social support and substance use in early adolescence. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1989;12(4):321–339. doi: 10.1007/BF00844927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]