Abstract

Background

Food insecurity is a public health concern and it is estimated to affect 18 million American households nationally, which can result in chronic nutritional deficiencies and other health risks. The relationships between food insecurity and specific demographic and geographic factors in Wisconsin is not well documented. The goals of this paper are to investigate socio-demographic and geographic features associated with food insecurity in a representative sample of Wisconsin adults.

Methods

This study used data from the Survey of the Health of Wisconsin (SHOW). SHOW annually collects health-related data on a representative sample of Wisconsin residents. Between 2008-2012, 2,947 participants were enrolled in the SHOW study. The presence of food insecurity was defined based on the participant's affirmative answer to the question “In the last 12 months, have you been concerned about having enough food for you or your family?”

Results

After adjustment for age, race, and gender, 13.2% (95% Confidence Limit (CI): 10.8%-15.1%) of participants reported food insecurity, 56.7% (95% CI: 50.6%-62.7%) of whom were female. Food insecurity did not statistically differ by state public health region (p=0.30). The adjusted prevalence of food insecurity in the urban core, other urban, and rural areas of Wisconsin was 14.1%, 6.5% and 10.5%, respectively. These differences were not statistically significant (p=0.13).

Conclusions

The prevalence of food insecurity is substantial, affecting an estimated number of 740,000 Wisconsin residents. The prevalence was similarly high in all urbanicity levels and across all state public health regions in Wisconsin. Food insecurity is a common problem with potentially serious health consequences affecting populations across the entire state.

Food insecurity is a complex economic and public health issue. Defined as “limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods or limited or uncertain ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways,”1 food insecurity has a variety of health implications. It is associated with chronic diseases and poor metabolic control,2,3 decreased mental health and cognitive performance,4-6 medication underuse and cost-related non-adherence,7,8 and less healthful eating. 9

Food insecurity is a public health concern nationally and across different regions of the United States. It is estimated that 18 million American households have experienced food insecurity.10 According to 1999-2006 estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), about 21.5% of Americans were characterized as having marginal, low, or very low food security.11 The relationships between food insecurity and specific demographic and geographic factors in Wisconsin have not yet been investigated.

In order to take on a focused research effort on these issues in Wisconsin, it is important to first investigate characteristics of the state's food insecure population and the prevalence of food insecurity in different geographic areas and urbanicity levels across the state. We used data from the 2008-2012 waves of the Survey of the Health of Wisconsin (SHOW) to investigate socio-demographic and regional differences in food insecurity. We hypothesized that the prevalence of food insecurity would be similar across state public health regions and would be different across various levels of urbanicity within the state (i.e., higher in urban areas). No previous study, of which we are aware, has directly investigated differences in food insecurity between areas of varying urbanicity and geography within a particular state, and such results could be key components in future attempts to develop targeted policies and address food insecurity in Wisconsin.

Methods

Data Collection

The SHOW is an examination based health survey which between 2008 and 2012 recruited a representative sample of 2,947 Wisconsin residents. The SHOW study rationale and methods have been previously described.12 Briefly, a two-stage cluster sampling method was used to randomly select census block groups and households in order to recruit study participants age 21-74 years. Participants were surveyed about their health, demographics, behaviors, and lifestyle. Participants also completed a physical exam measuring anthropometrics and blood pressure, and provided blood and urine samples for future analyses.

Food Insecurity

The presence of food insecurity was defined based on the participant's affirmative answer to the question “In the last 12 months, have you been concerned about having enough food for you or your family?” This question is aligned with items included in the US Department of Agriculture Food Security Survey Module used in NHANES to estimate individuals with low and very low food security. After excluding those participants who did not answer this food security question, the sample size for the analyses reported here was 2,552.

Predictors and Covariates

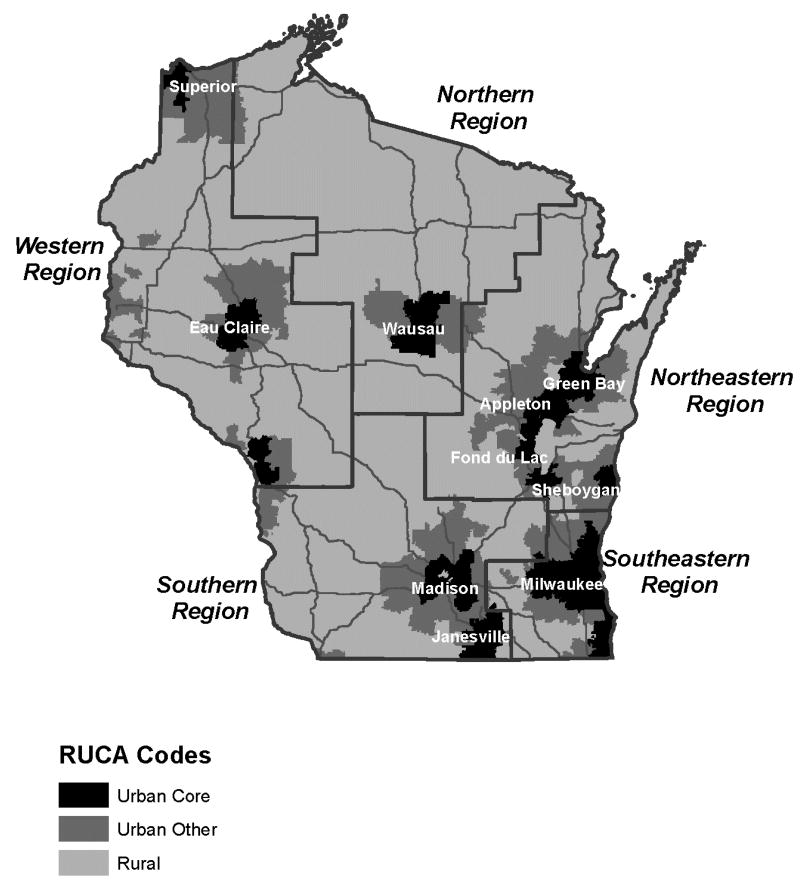

Participants were assigned into 5 public health regions of the state according to the categorization used by the Wisconsin Department of Health Services. They were also assigned into 3 urbanicity categories based on the University of Washington Rural-Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) Code corresponding to their census block group.13 Urban core describes a location in or very near the center of a largely populated area, while other urban describes a location that is suburban and distinct from a primarily rural or urban core area. All other RUCA code groups were placed into a single rural category. This resulted in a 3-category classification including urban core, other urban, and rural (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Rural-Urban Classification of Census Block Groups in Wisconsin.

Socio-demographic information collected from participants included highest level of education completed, household income, type of health insurance, and race and ethnicity. Educational level was assessed based on the participant's reported years of education completed and categorized into a binary variable by comparing the participants who received up to a high school diploma or equivalent to all other participants. Income was classified into 4 categories: those who earned <200%, between 200-299%, between 300-499%, and ≥500% of the federal poverty line (FPL). Income was also analyzed as a binary variable by comparing the population who earned less than 200% of the FPL to all other participants. The various types of health insurance used by participants were categorized into private, public Medicaid, and public Medicare. Participants who had no insurance in the previous 12 months were considered to have no health insurance.

Information on participants' general health included derived measures of self-reported health, diabetes, and hypertension. Participants were asked to describe their health status as excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor. Health status was made into a binary variable by comparing participants who rated their health as fair or poor to all other participants. Diabetes was defined based on hemoglobin A1C ≥6.5% or self-reported physician-diagnosed diabetes. Hypertension was identified in participants with systolic pressure ≥140 mmHg, diastolic pressure ≥90 mmHg, or who reported currently taking an anti-hypertensive medication.

Data Analysis

SAS version 9.3 software was used to conduct data analyses. All statistical analyses accounted for the complex survey design used by the SHOW study. Logistic regression models (PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC) were used to estimate crude and adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of food insecurity according to level of urbanicity, health region, and other sociodemographic variables. Direct standardization to the Wisconsin population using US census data was used to obtain Wisconsin socio-demographic adjusted prevalences.

Results

Table 1 provides the gender, age, and race-adjusted characteristics of SHOW participants who answered the food security item. A total of 13.2% (95% Confidence Limit (CI): 10.8%-15.1%) of respondents reported food insecurity, 56.7% (95% CI: 50.6%-62.7%) of whom were female. Those reporting food insecurity were younger on average (mean age 41.1) than those who were food secure (mean age 46.1). This difference was statistically significant (p-value <0.0001). The proportion of minority racial groups among those reporting food insecurity (24.2%) was higher than among those who did not (10.0%, p<0.001). Mean BMI was about 1 kg/m2 higher in food insecure than in food secure participants, but the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.12). Likewise, diabetes prevalence was almost 80% higher among food insecure (10.2%) than among secure subjects (5.7%), but the difference was only borderline statistically significant (p=0.07). Participants reporting food insecurity had significantly lower socioeconomic status as reflected by a lower educational level (p=0.002) and lower income (p<0.001) as well as worse self-reported health status (p<0.001).

Table 1. Characteristics of eligible SHOW participants by Food Security status, Survey of the Health of Wisconsin 2008-2012*.

| Secure | Insecure | P- value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n=2246 | n=306 | ||

| Female, % | 49.4 | 57.0 | 0.04 |

| Age, mean | 46.1 | 41.1 | <0.001 |

| Self-reported race, % | |||

| Non-Hispanic White (%) | 90.0 | 75.8 | <0.001 |

| BMI, mean | 29.5 | 30.6 | 0.12 |

| Diabetes (>6.5 A1C or self-reported), % | 5.7 | 10.2 | 0.07 |

| Hypertension (>140/90 or currently on anti-hypertensive medication), % | 29.4 | 23.8 | 0.1 |

| Education, % | |||

| High school diploma or less, % | 24.9 | 35.9 | 0.002 |

| Income, % | |||

| <200% FPL, % | 25.5 | 60.1 | <0.001 |

| Health Insurance, % | |||

| None (0 months of previous 12 months with insurance), % | 5.7 | 16.1 | <.0001 |

| Health status | |||

| Fair/Poor, % | 8.6 | 22.3 | <0.001 |

Estimates adjusted for age, gender, and race

Table 2 shows the gender-, age-, and race-adjusted prevalence of food insecurity for each of five Wisconsin health regions. The percentage of those participants assigned to the Southeast, South, West, North, and Northeast health regions who reported food insecurity was 13.8%, 9.5%, 9.5%, 8.7%, and 14.1% respectively. These differences were not statistically significant (p-value: 0.30). The adjusted prevalence of food insecurity in the urban core, other urban, and rural areas of Wisconsin was 14.1%, 6.5%, and 10.5% respectively. These differences were also not statistically significant (p-value: 0.13). Age-, gender-, and race-adjusted pairwise analysis comparing urban and rural areas also showed no statistically significant differences in the prevalence of food insecurity (p-value: 0.18).

Table 2. Regional variation of food insecurity, Survey of the Health of Wisconsin 2008-2012*.

| Number | Food insecure* (%) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Region | Southeast | 701 | 13.8 | |

| South | 543 | 9.5 | ||

| West | 398 | 9.5 | ||

| North | 374 | 8.7 | ||

| Northeast | 543 | 14.1 | 0.30 | |

| Urbanicity (RUCA) | Urban core | 1210 | 14.1 | |

| Other urban | 384 | 6.5 | ||

| Rural | 965 | 10.5 | 0.13 |

Estimates adjusted for age, gender, and race

The results of multivariate logistic regression analyses on the relation between urbanicity and the odds of food insecurity are presented in Table 3. The age-, gender-, and race-adjusted odds ratio of food insecurity was about 33% higher in participants from urban areas compared to rural areas (a not statistically significant odds ratio, 95% CI: 0.9-2.1). In the full model that also included both education and income levels, food insecurity was still elevated in urban areas, but this elevation was not statistically significant. In the full model only low income level was a significant predictor of food insecurity. Participants reporting household income <200% and 200-299% of the FPL had significantly increased odds of reporting food insecurity compared to participants reporting household income >500% of the FPL even after adjusting for all the other covariates in the model.

Table 3. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for food insecurity adjusted by various sets of covariates, Survey of the Health of Wisconsin 2008-2012.

| Adjusted for demographics* | Fully Adjusted* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| OR | 95% CI | P-Value | OR | 95% CI | P-Value | |

| Urbanicity | ||||||

| Urban | 1.33 | 0.85-2.08 | 1.57 | 0.94-2.65 | ||

| Other Urban | 0.57 | 0.24-1.38 | 0.73 | 0.29-1.86 | ||

| Rural | 1 | Reference | 0.13 | 1 | Reference | 0.14 |

| Age (One year increase) | 0.97 | 0.96-0.99 | <0.001 | 0.99 | 0.97-1.00 | 0.08 |

| Gender (Female vs Male) | 1.34 | 1.00-1.79 | 0.05 | 1.31 | 0.96-1.79 | 0.09 |

| Race | ||||||

| White, Non-Hispanic | 1 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| African American, Non-Hispanic | 3.52 | 2.02-6.11 | 1.88 | 0.86-4.10 | ||

| Hispanic | 3.10 | 1.61-5.97 | 3.10 | 1.32-7.28 | ||

| Other Race | 1.35 | 0.50-3.65 | <0.001 | 1.12 | 0.46-2.77 | 0.06 |

| Education | ||||||

| <High School Diploma | 1.38 | 0.64-2.98 | ||||

| High School Diploma or Equiv. | 1.50 | 0.84-2.69 | ||||

| Some College | 1.58 | 1.00-2.49 | ||||

| ≥4 Yr College | 1 | Reference | 0.26 | |||

| Poverty Income Ratio | ||||||

| <200% FPL | 13.39 | 7.06-25.42 | ||||

| 200-299 %FPL | 9.53 | 5.14-17.69 | ||||

| 300-499% FPL | 2.02 | 0.92-4.42 | ||||

| ≥500% FPL | 1.0 | Reference | <0.001 | |||

Demographic variables: age, gender, and race; fully adjusted model added socioeconomic variables (education, income). OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; FPL: federal poverty level.

Discussion

Our results show that more than one in every ten Wisconsin resident (about 13%) surveyed between 2008 and 2012 reported being “concerned about having enough food” for the family sometime in the previous year before the survey. This result may be underestimating the true prevalence of food insecurity because it relies on only one measure and does not examine individuals with potentially limited food access defined by the USDA and other national studies as “marginal food security.”1,14

Our finding is consistent with another recent Wisconsin telephone-based survey that reported a 15.8% prevalence of food insecurity that also used a similar one-question proxy to the 18-question United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Household Food Screener to estimate food insecurity.15 The USDA Household Food Security Questionnaire was added to the SHOW survey in 2012. Using SHOW data from 2012 we estimate that 26.5% of Wisconsin residents have marginal, low, or very low food security (95% CI: 20.1%-32.9%). This measure is more comparable to the 21.5% estimate obtained by NHANES that also uses the USDA Food Security Questionnaire.1,14 The 21.5% estimate was obtained using 1999-2006 data so additional adjustment to account for the economic recession would likely make these estimates more comparable. The measure used in this study highly correlates with low and very low food security definitions used by the USDA (r=0.93).

Notably, the prevalence of food insecurity was not significantly different across the five designated public health regions of Wisconsin, suggesting that this is a concern throughout the entire state. Although slightly higher in urban areas, the difference in prevalence of food insecurity between rural and urban areas was not statistically significant across the state. To our knowledge, only one other study has directly compared food insecurity prevalence between urban and rural populations within a particular geographical area in Texas, and results of that study suggested that the rural populations had a greater prevalence of food insecurity compared to urban populations.16 These results contribute to this ongoing field of study by demonstrating that, rather than exclusively an urban problem, rural areas are also extensively affected by poverty and food insecurity.

Results from our analyses of the correlates of food insecurity in Wisconsin (Table 1) confirm those previously shown in national studies and local studies in other parts of the United States. A greater percentage of food insecure compared to secure participants were female, in agreement with results from a longitudinal national sample of young adults showing that food insecurity is more common among women than men.17 There was a greater percentage of non-Hispanic African-American and Hispanic participants among the food insecure compared to food secure population, which has been a trend in previous studies.2,3,15 Socioeconomic characteristics including less education and lower income have been associated with food insecurity previously.2,3,15 Similarly, results of this analysis indicated that a greater percentage of the food insecure population earned up to a high school diploma or equivalent and had an income that was less than 200% of the federal poverty line. In addition, a greater percentage of food insecure SHOW participants reported fair or poor health and had worse mental health compared to food secure participants. Lower health status and mental disorders have previously been associated with food insecurity.4,18-20 There are discrepancies in the literature regarding the relationships between food insecurity, age, and BMI. Results from this analysis indicate that the food insecure population was younger in age and had a non-statistically significant greater BMI than the food secure population, which confirms several studies with similar results.2,3,15,17,21,22

A particularly important contribution of this study is the inclusion of the other urban, or suburban, category. While a number of studies have reported the prevalence of food insecurity in rural and urban populations, most have failed to report information on suburban populations. Although hunger in suburban families has very often been overlooked, our results suggest that food insecurity in suburban areas, although less prevalent than in urban or rural areas, is present (affecting about 6.5% of suburban residents) which potentially is a reflection of the changing demographic landscape and potential move of more affluent younger individuals into urban cores. In fact, in this study there were no statistically significant differences between urbanicity levels, suggesting the problem is pervasive regardless of geography. Findings are consistent with a previous study conducted in 2010 that estimated 6.2 million suburban households were food insecure.14 It will be important to continue to study all populations regardless of urbanicity level in future studies of food insecurity.

Conclusion

Demographic associations with food insecurity in Wisconsin are consistent with those found in national surveys. Interestingly, there were no significant differences in food insecurity prevalence across public health regions or varying levels of urbanicity (urban, suburban, or rural). Perhaps counter to perceptions that food security is only an urban-poor problem, the prevalence of food insecurity was similarly high (non-statistically different) across all urbanicity levels. Overall, food insecurity is a common problem with potentially serious health consequences affecting more than an estimated 740,000 Wisconsin residents.

Acknowledgments

In addition to study participants, the authors would like to thank all the individuals who helped to collect, manage, and organize the SHOW data. This study was funded by the Wisconsin Partnership Program PERC Award (PRJ56RV), National Institutes of Health's Clinical and Translational Science Award (5UL 1RR025011), and National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (1 RC2 HL101468).

References

- 1.B G, N M, P C, H W, C J. In: Guide to Measuring Household Food Security, Revised 2000. USDA, editor. Alexandria, VA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seligman HK, Laraia BA, Kushel MB. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J Nutr. 2010;140(2):304–10. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.112573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berkowitz SA, Baggett TP, Wexler DJ, Huskey KW, Wee CC. Food insecurity and metabolic control among U.S. adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(10):3093–9. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Alegría M, Jane Costello E, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Kessler RC. Food insecurity and mental disorders in a national sample of U.S. adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(12):1293–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Melchior M, Chastang JF, Falissard B, Galéra C, Tremblay RE, Côté SM, Boivin M. Food insecurity and children's mental health: a prospective birth cohort study. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e52615. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao X, Scott T, Falcon LM, Wilde PE, Tucker KL. Food insecurity and cognitive function in Puerto Rican adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(4):1197–203. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Billimek J, Sorkin DH. Food insecurity, processes of care, and self-reported medication underuse in patients with type 2 diabetes: results from the California Health Interview Survey. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(6):2159–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01463.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bengle R, Sinnett S, Johnson T, Johnson MA, Brown A, Lee JS. Food insecurity is associated with cost-related medication non-adherence in community-dwelling, low-income older adults in Georgia. J Nutr Elder. 2010;29(2):170–91. doi: 10.1080/01639361003772400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bauer KW, Widome R, Himes JH, Smyth M, Rock BH, Hannan PJ, Story M. High food insecurity and its correlates among families living on a rural American Indian Reservation. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(7):1346–52. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.C-J A, N M, A M, C S. In: Statistical Supplement to Household Food Security in the United States in 2011. USDA, editor. Alexandria, VA: 2012. AP-058. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gowda C, Hadley C, Aiello AE. The association between food insecurity and inflammation in the US adult population. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(8):1579–86. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nieto FJ, Peppard PE, Engelman CD, McElroy JA, Galvao LW, Friedman EM, Bersch AJ, Malecki KC. The Survey of the Health of Wisconsin (SHOW), a novel infrastructure for population health research: rationale and methods. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:785. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morrill R, Cromartie J, Hart L. Metropolitan, urban, and rural communting area: toward a better depiction of the US settlement system. Urban Geography. 1999;20:727–748. [Google Scholar]

- 14.C-J A, N M, A M, C S. In: Household food security in the United States in 2010. USDA, editor. Service USDoAER; Sep, 2011. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pan L, Sherry B, Njai R, Blanck HM. Food insecurity is associated with obesity among US adults in 12 states. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(9):1403–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharkey JR, Johnson CM, Dean WR. Relationship of household food insecurity to health-related quality of life in a large sample of rural and urban women. Women Health. 2011;51(5):442–60. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2011.584367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gooding HC, Walls CE, Richmond TK. Food insecurity and increased BMI in young adult women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012;20(9):1896–901. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryu JH, Bartfeld JS. Household food insecurity during childhood and subsequent health status: the early childhood longitudinal study--kindergarten cohort. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(11):e50–5. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lent MD, Petrovic LE, Swanson JA, Olson CM. Maternal mental health and the persistence of food insecurity in poor rural families. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20(3):645–61. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huddleston-Casas C, Charnigo R, Simmons LA. Food insecurity and maternal depression in rural, low-income families: a longitudinal investigation. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(8):1133–40. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008003650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karnik A, Foster BA, Mayer V, Pratomo V, McKee D, Maher S, Campos G, Anderson M. Food insecurity and obesity in New York City primary care clinics. Med Care. 2011;49(7):658–61. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31820fb967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Metallinos-Katsaras E, Must A, Gorman K. A longitudinal study of food insecurity on obesity in preschool children. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(12):1949–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]