Abstract

Background

Before the advent of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, radiotherapy and surgery alone were associated with a high risk of uncontrolled locoregional relapses in locally advanced breast cancer (LABC).

Material and methods

In the 1990s we initiated two neoadjuvant protocols, where patients with LABC were given either doxorubicin qW or 5-fluorouracil/mitomycin (FUMI) q3W to shrink the tumours prior to mastectomy and postoperative radiotherapy. Previously, we reported TP53 mutation status to predict a poor response to chemotherapy. Here, we present the long-term survival data, with a follow-up of 20 years in the doxorubicin (n = 90) and 15 years in the FUMI trial (n = 34).

Results

Patients in the doxorubicin trial with TP53-mutated tumours experienced a shorter recurrence-free (RFS; 14 vs. 83 months, p < 0.001) and overall survival (OS; 35 vs. 90 months, p < 0.001) than patients with TP53 wt tumours. Similarily, TP53 mutations were associated with a shorter OS (22 vs. 80 months, p = 0.03) and a tendency to shorter RFS (17 vs. 33 months, p = 0.06) in patients treated with FUMI. Furthermore, axillary lymph node metastases predicted shorter OS, but only in patients treated with doxorubicin (49 vs. 142 months, p < 0.04). Applying multivariate analysis, TP53 mutations predicted inferior RFS (p < 0.001) as well as OS (p < 0.001), independently of axillary lymph node status. Isolated local recurrences, without simultaneous distant metastases, occurred in seven patients only in the two trials. Interestingly, chest wall radiation fibrosis predicted improved OS (p = 0.004).

Conclusion

TP53 inactivating mutations are associated with an inferior long-term prognosis in patients with LABC treated with conventional chemotherapy.

Traditionally treated with radiotherapy, with or without additional surgery, patients with locally advanced breast cancer (LABC) frequently experienced intractable locoregional relapses and subsequently died of their disease [1–5]. Following the implementation of chemotherapy regimens for metastatic breast cancer, and subsequent, adjuvant therapy in early breast cancer, studies were undertaken to test these regimens as primary treatment of LABC [3,4,6,7].

In 1991, we initiated our first clinical trial in LABC evaluating low-dose, weekly doxorubicin [8,9], a regimen commonly used for metastatic breast cancer at that time [10,11]. Subsequently, from 1997, we conducted a trial in which we applied a combined regimen of 5-fluorouracil and mitomycin (FUMI) to patients with LABC [12], based on promising concurrent data from patients with metastatic breast cancer [13,14]. Both protocols included pre- treatment snap-frozen surgical biopsies for predictive factor analysis. Previously, we reported TP53 mutation status to predict for an inferior anti-tumour response in both studies [9,12]. While others have reported the prognostic impact of TP53 mutation status [15–17], the long-term (10 years and beyond), relapse-free and overall survival (OS) data with respect to TP53 mutation status in patients treated with defined drug regimens in prospective studies are lacking. Here, we report the long-term outcome for all patients participating in the doxorubicin and FUMI trials, with a cut-off time from patient inclusion to final update of the database of 20 years for the doxorubicin and 15 years for the FUMI study.

Material and methods

Patient and tumour characteristics are given in Table I. Apart from human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) analysis these characteristics are based upon data published previously [9,12]. HER2 fluorescent in situ hybridisation (FISH) was performed on fresh frozen tumour samples using the Vysis LSI TOP2A SpectrumOrange/HER-2 SpectrumGreen/CEP 17 SpectrumAquaTM Probe kit. Unfortunately, breast cancer tissue for HER2 FISH analysis was available only from 30 patients (of 90) in the doxorubicin trial. TP53 mutation status was assessed by cDNA sequencing previously, and predicted for inferior drug response and worse short-term survival in both studies [8,9]. In the current analysis, we evaluated the long-term prognostic impact of TP53 mutation status with respect to RFS as well as OS.

Table I.

Baseline patient and tumour characteristics.

| Study I Doxorubicin |

Study II FUMI |

|

|---|---|---|

| Accrual period | Jan 1991–Mar 1997 | Jun 1993–Feb 2001 |

| Age (years) | ||

| range | 32–88 | 37–82 |

| median | 64 | 67 |

| T stage | ||

| T21 | 3 | 2 |

| T3 | 54 | 15 |

| T4 | 33 | 17 |

| N stage | ||

| N02 | 30 | 9 |

| N1 | 34 | 14 |

| N2 | 26 | 11 |

| M stage | ||

| M0 | 78 | 24 |

| M1 | 12 | 10 |

| Tumour type | ||

| IDC | 75 | 30 |

| ILC | 8 | 43 |

| Other | 7 | |

| Grade | ||

| I | 23 | 0 |

| II | 42 | 16 |

| III | 25 | 18 |

| ER status | ||

| Negative4 | 13 | 11 |

| Positive | 77 | 23 |

| HER2 status | ||

| Negative5 | 24 | 27 |

| Positive | 6 | 6 |

| No data | 60 | 1 |

| TP53 status | ||

| TP53 wt | 64 | 16 |

| TP53 mut. | 26 | 18 |

| TP53 wt + non L2/L3 mut. | 71 | 24 |

| TP53 L2/L3 mut | 19 | 10 |

IDC, infiltrating ductal carcinoma; ILC, infiltrating lobular carcinoma.

T stage and all subsequent tumour characteristics given for stage 3 and 4 combined. T2 tumours only included if axilla stage N2;

N stage by clinical assessment alone;

ILC or poorly differentiated, not subclassified further;

ER negative if tumour ER concentration < 10 fmol/mg;

HER2 in situ hybridisation.

Both trials enrolled patients suffering from LABC (T3/T4 and/or N2/N3), considered unfit for primary surgery. Common to both trials, all patients underwent staging with x-ray imaging of the chest, spine, and pelvis, liver ultrasound examination and a bone scan before commencing chemotherapy. As the primary aim of both protocols were to: 1) downstage locally advanced tumours, making them fit for surgery, and 2) evaluate factors predicting response to therapy, patients with LABC and limited distant metastases for whom optimal local therapy was defined as the primary therapeutic target were eligible for inclusion. The study protocols were approved by the Regional Ethical Committee of the Western health region in Norway (reference numbers: 192/91-69.91, 39/92-69.91 and 06/597), and all patients gave their informed consent before inclusion.

Study I

Doxorubicin (14 mg/m2) was administered i.v. weekly, scheduled for 16 weeks, with four-weekly assessment of clinical response. Ninety patients were included in the final analysis [9]. Of these, 78 patients did not reveal any signs of distant metastases at the time of diagnosis. All patients were enrolled between January 1991 and March 1997.

Study II

In the FUMI trial 5-fluorouracil 1000 mg/m2 day 1 and 2 and mitomycin 6 mg/m2 day 2 was administered i.v. every three weeks, scheduled for a total of four cycles, with assessment of clinical response before every cycle. Thirty-four patients were included in the final analysis [12]. Of these, 24 patients did not reveal any signs of distant metastases at the time of diagnosis. All patients were enrolled between June 1993 and February 2001.

Response rates and short-term survival data in the doxorubicin and FUMI trials have been described in detail previously [9,12]. Clinical response was evaluated according to the UICC criteria, commonly used at that time. The primary scientific aim of the trials was to identify potential biomarkers predictive of drug resistance, defined as tumours with progressive disease (PD). The prescribed treatment was stopped if PD occurred. Doxorubicin was the only chemotherapy used presurgically in Study I, apart from one patient included in 1997 who received docetaxel as second line treatment subsequent to progressing on doxorubicin. In Study II, seven patients switched to docetaxel and eight patients to anthracyclines due to inadequate tumour response on FUMI. The reason for not switching more patients to another cytotoxic regimen in Study I was the lack of alternative, potent drugs until the introduction of taxanes in the late 1990s.

Following chemotherapy, patients went on to mastectomy with surgical exploration of the axilla (removal of enlarged lymph nodes) and radiotherapy to the chest wall, axilla and supraclavicular fossa. Patients deemed inoperable subsequent to primary chemotherapy (n = 11 in the doxorubicin and n = 11 in the FUMI trial) received radiotherapy alone to the breast and regional lymph nodes. Radiotherapy was administered as 50 Gy/25 fractions to the chest wall (or breast) and axilla and 48 Gy/24 fractions to the supraclavicular area. Additionally, two patients with stable disease (SD) and one patient with partial response (PR) in the two trials combined received a radiotherapy boost (10 Gy/5 fractions) due to tumour-on-ink in the pathological mastectomy specimen.

Patients with an oestrogen or progesterone receptor positive breast cancer (ER or PGR ≥ 10 fmol/mg protein) received adjuvant tamoxifen 30 mg daily for five years in both studies. ER/PGR levels were measured as described previously [18], and ER positivity set at ≥ 10 fmol/mg is in accordance with tumours considered ER positive by immunohistochemistry in routine diagnostics today [19]. The median follow-up time was defined from inclusion in the study up to 25 April 2013 (234 months for the doxorubicin study, 177 months for the FUMI study). Recurrence-free survival (RFS) was calculated for patients with stage 3 disease, and defined as the time from inclusion to a clinical or radiological confirmed recurrence of breast cancer, whereas OS was assessed for stage 3 and stage 3/4 separately. In a patient with PD who never became disease-free, the RFS was set as zero.

Conflicting evidence has linked radiation-induced fibrosis to subsequent local tumour control [20–22]. Based on clinical observations, we hypothesised that patients in the two trials who developed extensive radiation fibrosis would have an improved survival outcome. A total of 46 patient records contained data regarding chest wall status during long-term follow-up. For these patients, the correlation between radiation fibrosis and tumour response to chemotherapy as well as OS was assessed. Furthermore, data regarding the expression of the DNA repair enzyme ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) was extracted from a recently conducted study [23] and analysed for its relationship to radiation fibrosis.

Statistical analysis

Survival analysis was performed by Kaplan-Meier plots, and patient subgroups were compared by the log-rank test. Deaths for reasons other than breast cancer, or patients still alive at the time of analysis, were treated as censored observations. Multivariate survival analysis was performed using Cox regression. Mann-Whitney rank test was used for comparison of ATM levels between patients’ subgroups, whereas Fisher Exact test was used to compare the number of patients with radiation fibrosis in the different response groups. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS 15.0/PASW 17.0 software package (SPSS Inc.) and/or Simple Interactive Statistical Analysis (SISA). All p-values reported are two-tailed.

Results

In the doxorubicin trial, median RFS (stage 3 disease only) and OS (stage 3 & 4) was 48 months and 56 months, respectively, in the total cohort, with an OS of 67 months if patients with distant metastases at inclusion (n = 12) were excluded from the analysis (Figure 1A, B). In the FUMI trial, the median RFS and OS was 22 and 32 months, respectively, with an OS of 35 months if patients with distant metastases (n = 10) were excluded (Figure 1C, D).

Figure 1.

(A–D) Recurrence-free and overall survival in patients with locally advanced breast cancer after neoadjuvant doxorubicin (Dox) qW (16 weeks) or 5-FU/mitomycin (FUMI) q3w (12 weeks). (E–H) Survival related to tumour response group. OS, overall survival; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; RFS, recurrence-free survival; SD, stable disease. Number of patients per group given in parenthesis (patients with stage IV disease excluded). Censored values are marked with +.

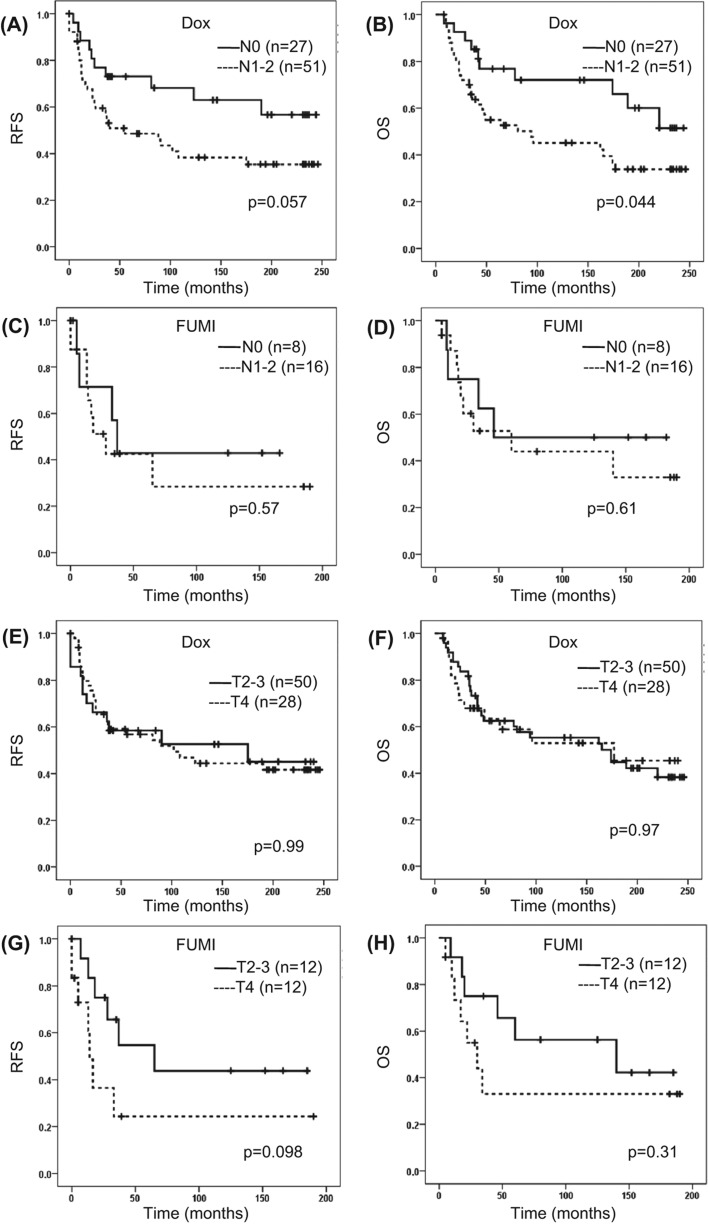

Response rates were reported previously [9,12]. Thus, while 38% and 32% (stage 3 & 4 combined) of the patients obtained PR in the doxorubicin and FUMI studies respectively, no patient obtained a complete response in neither study [9,12]. The long-term survival data for the different response groups are given in Figure 1E, H. Patients obtaining a PD on doxorubicin had significantly worse survival outcome than those who responded with SD or PR (Figure 1E, F), whereas no significant difference in survival between the response groups was recorded in the FUMI trial (Figure 1G, H). When we compared the survival outcome between patients obtaining a PR versus patients having a SD, no significant difference was recorded either within the doxorubicin or within the FUMI group (Figure 1E–H). In patients who derived a clinical benefit (PR or SD) from the neoadjuvant chemotherapy, the frequency of local recurrences was 21% in the doxorubicin and 28% in the FUMI trial. In general, these local relapses occurred synchronous to distant metastases; 18 of 22 cases in the doxorubicin and 10 of 13 cases in the FUMI trial). Isolated local recurrences, without simultaneous distant metastases, occurred only in four patients in the doxorubicin and three patients in the FUMI trial. A clinically negative axilla (N0 versus N1/2) prior to chemotherapy was associated with improved long-term outcome in the doxorubicin, but not the FUMI trial (Figure 2A–D). No effect of tumour T-stage (T2/3 vs. T4) on survival outcome was recorded in the two trials (Figure 2E–H). Also, no effect of hormone receptor status on long-term survival outcome was recorded in neither trial (data not shown). Breast cancer- specific mortality was 58% in the doxorubicin trial (52 of 90 patients) and 44% in the FUMI trial (15 of 34 patients), based on 20 and 15 years of follow-up.

Figure 2.

Survival related to pre-treatment clinical nodal (N) status (A–D) and tumour T-stage (E–H) in patients with locally advanced breast cancer given neoadjuvant doxorubicin or FUMI. OS, overall survival; RFS, recurrence-free survival. Number of patients per group given in parenthesis (patients with stage IV disease excluded). Censored values are marked with +.

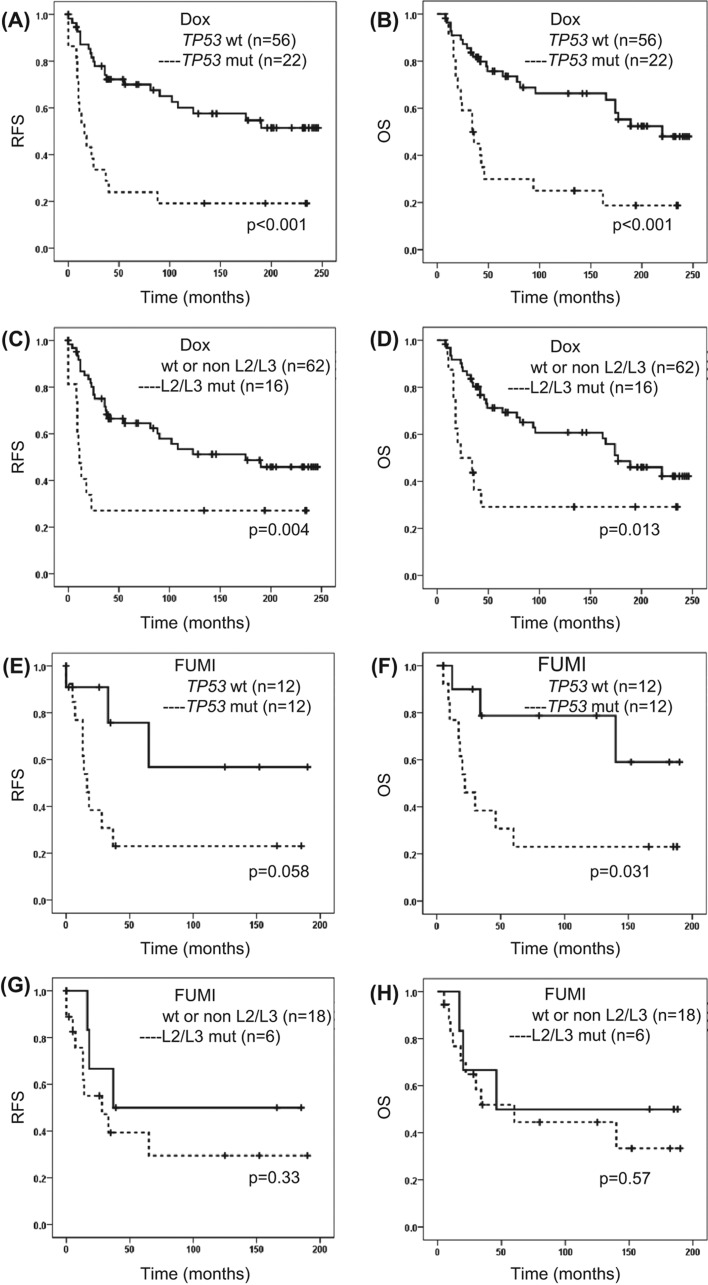

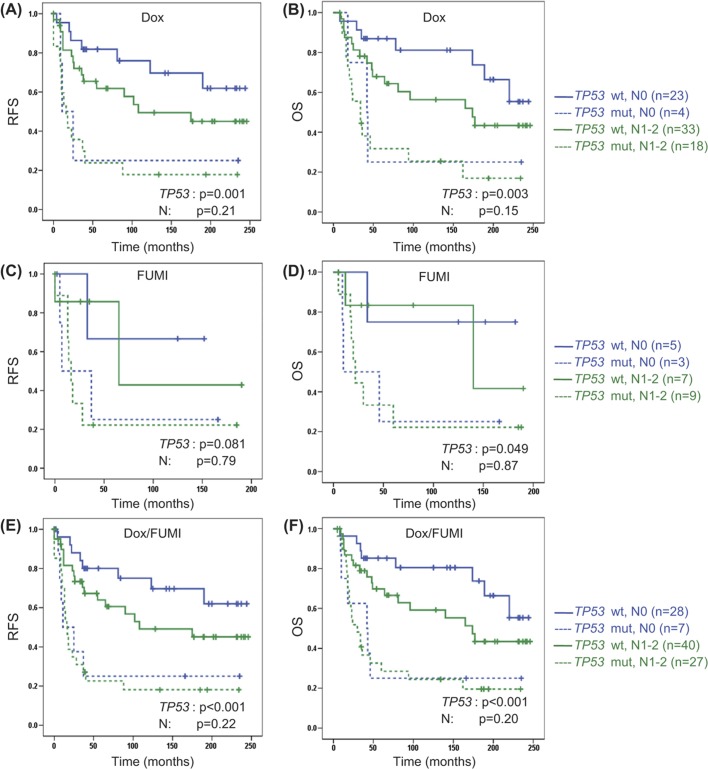

Tumour TP53 mutations were detected in 34% of the patients included in the doxorubicin and FUMI trials (Table I), whereas mutations in the essential L2/L3 DNA binding domains of TP53 occurred in 22% of the breast cancers [9,12]. Both TP53 mutations in total (Figures 3A, B) and TP53 mutations affecting the L2/L3 domains (Figures 3C, D) were associated with significantly inferior RFS as well as OS in the doxorubicin trial. TP53 mutations were associated with a borderline significant decline in RFS, and a significant decline in OS after FUMI treatment (Figure 3E, F). No significant effect was detected for TP53 mutations affecting the L2/L3 domains in the FUMI trial (Figure 3G, H), probably due to the low number of patients without distant metastases at diagnosis (n = 24). Combining patients from the two trials, TP53 mutations were associated with a significantly reduced RFS (p < 0.001) and OS (p < 0.001), whereas TP53 mutations affecting the L2/L3 domains were associated with a shortened OS (p = 0.006), but not a shorter RFS (p = 0.06). TP53 was mutated in four of seven patients who developed isolated local recurrences, without simultaneous distant metastases, in the two trials combined. Cox multivariate analysis was used to decipher whether TP53 mutation status or nodal status independently predicted survival outcome, and TP53 mutation status remained the sole parameter predicting survival in the doxorubicin and FUMI trials, including the combined analysis of the two trials (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Survival related to tumour TP53 mutation or TP53 L2/L3 domain mutation status in patients with locally advanced breast cancer given neoadjuvant doxorubicin (A–D) or FUMI (E–H). OS, overall survival (patients with stage IV disease excluded); RFS, recurrence-free survival. Number of patients per group given in parenthesis. Censored values are marked with +.

Figure 4.

Multivariate analysis of survival outcome with respect to tumour TP53 and clinical nodal status (N) in patients with locally advanced breast cancer from the doxorubicin trial (A,B), the FUMI trial (C,D) or the two trials combined (E,F). OS, overall survival (patients with stage IV disease excluded); RFS, recurrence-free survival. Number of patients per group given in parenthesis. Censored values are marked with +.

An observational finding was the impact of chest wall fibrosis on long-term outcome. Radiation fibrosis developed in 19 of 46 patients whose chest wall status was described in the patient records (PR, SD and PD combined), and these patients derived a significantly prolonged OS (median: 139.5 months, p = 0.004), compared to those who did not develop fibrosis (median: 25.5 months). Due to the limited number of patients for whom this parameter was recorded it could not be entered into a multivariate model. This survival benefit in patients with fibrosis was evident both in chemotherapy responders (PR) and non-responders (SD and PD), and it was not related to differences in radiation dose in-between the patients. Furthermore, the improved survival in patients developing chest wall fibrosis was not related to TP53 mutation status, nor was it related to ATM expression levels previously found to be associated with response to chemotherapy in these patients [23].

Discussion

We demonstrated in 1996 that TP53 mutations predict a lack of response to low-dose doxorubicin [8]. This observation was later reconfirmed following an expansion of the initial trial [9], in addition to our subsequent study [12] evaluating the impact of TP53 status on response to the FUMI regimen. In addition, studies by the breast cancer group in Vienna [24] as well as a recent study by our group [25] both reported a low response rate for TP53-mutated primary breast cancers treated with anthracyclines at three-weekly conventional doses. Importantly, while TP53 mutations are associated with a lack of sensitivity to anthracyclines and related compounds, and inferior short-term survival [9,17], the impact of TP53 mutation status on long-term outcome, beyond 10 years, has not been fully elucidated in a controlled setting. Here, we report the long-term prognostic effect of TP53 mutation status at 20 and 15 years follow-up in two populations treated according to well-defined regimens and with systematic assessment of anti-tumour response in two phase 2 trials.

The short-term (5-year) negative prognostic impact of TP53 mutations was demonstrated in the recent phase 3 EORTC 10994/BIG 1-00 trial with 928 breast cancer patients, but a predictive value of TP53 mutation status for anthracycline resistance was not seen in this trial [17]. The reason for this apparent discrepancy compared to our data could be due to higher anthracycline doses administered in the EORTC 10994/BIG 1-00 trial, but in particular the fact that these patients received cyclophosphamide and taxanes in concert. Notably, cyclophosphamide at high doses has been shown by others to compensate for anthracycline resistance in TP53-mutated human breast cancers [26], whereas TP53 status has not been found to predict for sensitivity to taxanes [24,27].

Notably, in multivariate analysis, TP53 mutation status was the only pre-treatment parameter to be associated with long-term outcome in our patient cohorts, and this finding extends the negative prognostic value of TP53 mutations from previous reports after 7.5–10 years [16] to currently 15–20 years observation. Additionally, we observed an association between extensive radiation fibrosis on the chest wall and improved long-term prognosis in a sub-group of patients for whom such data were available. Conflicting evidence has linked radiation fibrosis to local tumour control after radiotherapy, where certain patients seem especially sensitive to radiotherapy [20–22]. As both ATM and TP53 mutations have been related to radiation sensitivity [22,28], we compared ATM expression levels and ATM/TP53 mutation status, previously analysed in a subgroup of these patients [23], to fibrotic status, but no correlation between neither ATM nor TP53 status and radiation-induced fibrosis was recorded. While patients who developed chest wall fibrosis had prolonged OS, this finding could be confounded by increased time to develop fibrosis only in the long-time survivors.

Clearly, more efficient chemotherapy regimens and less toxic radiotherapy techniques have improved the outcome in patients with LABC quite extensively over the past 15–20 years, compared to treatment schedules given in the doxorubicin and FUMI trials. Thus, the clinical relevance of our findings relates to the persistent negative prognostic impact of TP53 inactivating mutations in LABC, observed after 15–20 years follow-up. While TP53 mutations are associated with inferior breast cancer prognosis in general, our findings reveal that the negative predictive value of TP53 mutation status in patients treated with an anthracycline or mitomycin-containing regimen translates into inferior long-term survival in locally advanced breast cancer.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the contribution made by the patients included in the doxorubicin and FUMI trials. Furthermore, the trials could not have been conducted without the skilful expertise of colleagues in the Departments of Oncology and Surgery at Haukeland University Hospital, and the technical assistance from S. Yndestad, H.B. Helle, N.K. Duong and D. Ekse.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest This work was supported by generous grants from Helse Vest, Bergen Medical Research Foundation, the Norwegian Cancer Society and the Rieber Foundation, Norway. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Haagensen CD, Stout AP. Carcinoma of the breast: II. Criteria of operability. Ann Surg. 1943;118:859–70. doi: 10.1097/00000658-194311850-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubens RD, Armitage P, Winter PJ, Tong D, Hayward JL. Prognosis in inoperable stage III carcinoma of the breast. Eur J Cancer. 1977;13:805–11. doi: 10.1016/0014-2964(77)90134-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swain SM, Sorace RA, Bagley CS, Danforth DN, Jr, Bader J, Wesley MN, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the combined modality approach of locally advanced nonmetastatic breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1987;47:3889–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hortobagyi GN, Ames FC, Buzdar AU, Kau SW, McNeese MD, Paulus D, et al. Management of stage III primary breast cancer with primary chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation therapy. Cancer. 1988;62:2507–16. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19881215)62:12<2507::aid-cncr2820621210>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bedwinek J, Rao DV, Perez C, Lee J, Fineberg B. Stage III and localized stage IV breast cancer: Irradiation alone vs irradiation plus surgery. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1982; 8:31–6. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(82)90381-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith IE, Jones AL, O’Brien ME, McKinna JA, Sacks N, Baum M. Primary medical (neo-adjuvant) chemotherapy for operable breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1993;29A:1796–9. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(93)90133-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubens RD, Sexton S, Tong D, Winter PJ, Knight RK, Hayward JL. Combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy for locally advanced breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1980;16:351–6. doi: 10.1016/0014-2964(80)90352-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aas T, Borresen AL, Geisler S, Smith-Sorensen B, Johnsen H, Varhaug JE, et al. Specific P53 mutations are associated with de novo resistance to doxorubicin in breast cancer patients. Nat Med. 1996;2:811–4. doi: 10.1038/nm0796-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geisler S, Lonning PE, Aas T, Johnsen H, Fluge O, Haugen DF, et al. Influence of TP53 gene alterations and c-erbB-2 expression on the response to treatment with doxorubicin in locally advanced breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2505–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nylen U, Baral E, Svane G, Rutqvist LE. Weekly doxorubicin in the treatment of metastatic breast carcinoma. Acta Oncol. 1989;28:515–7. doi: 10.3109/02841868909092261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chlebowski RT, Paroly WS, Pugh RP, Hueser J, Jacobs EM, Pajak TF, et al. Adriamycin given as a weekly schedule without a loading course: Clinically effective with reduced incidence of cardiotoxicity. Cancer Treat Rep. 1980;64:47–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geisler S, Borresen-Dale AL, Johnsen H, Aas T, Geisler J, Akslen LA, et al. TP53 gene mutations predict the response to neoadjuvant treatment with 5-fluorouracil and mitomycin in locally advanced breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:5582–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gundersen S, Kvinnsland S, Klepp O, Lund E, Hannisdal E, Host H. Chemotherapy with or without high-dose medroxyprogesterone acetate in oestrogen-receptor-negative advanced breast cancer. Norwegian Breast Cancer Group. Eur J Cancer. 1992;28:390–4. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(05)80060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mattsson W, von Eyben F, Hallsten L, Bjelkengren G. A phase II study of combined 5-fluorouracil and mitomycin C in advanced breast cancer. Cancer. 1982;49:217–20. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820115)49:2<217::aid-cncr2820490203>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bergh J, Norberg T, Sjogren S, Lindgren A, Holmberg L. Complete sequencing of the p53 gene provides prognostic information in breast cancer patients, particularly in relation to adjuvant systemic therapy and radiotherapy. Nat Med. 1995;1:1029–34. doi: 10.1038/nm1095-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olivier M, Langerod A, Carrieri P, Bergh J, Klaar S, Eyfjord J, et al. The clinical value of somatic TP53 gene mutations in 1,794 patients with breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1157–67. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonnefoi H, Piccart M, Bogaerts J, Mauriac L, Fumoleau P, Brain E, et al. TP53 status for prediction of sensitivity to taxane versus non-taxane neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer (EORTC 10994/BIG 1-00): A randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:527–39. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70094-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thorsen T. Occupied and unoccupied oestradiol receptor in human breast tumour cytosol. J Steroid Biochem. 1980;13:405–8. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(80)90346-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harvey JM, Clark GM, Osborne CK, Allred DC. Estrogen receptor status by immunohistochemistry is superior to the ligand-binding assay for predicting response to adjuvant endocrine therapy in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1474–81. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.5.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dikomey E, Borgmann K, Peacock J, Jung H. Why recent studies relating normal tissue response to individual radiosensitivity might have failed and how new studies should be performed. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;56:1194–200. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00188-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peters LJ. The ESTRO Regaud lecture. Inherent radiosensitivity of tumor and normal tissue cells as a predictor of human tumor response. Radiother Oncol. 1990;17:177–90. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(90)90202-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.West CM. Invited review: Intrinsic radiosensitivity as a predictor of patient response to radiotherapy. Br J Radiol. 1995;68:827–37. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-68-812-827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knappskog S, Chrisanthar R, Lokkevik E, Anker G, Ostenstad B, Lundgren S, et al. Low expression levels of ATM may substitute for CHEK2 /TP53 mutations predicting resistance towards anthracycline and mitomycin chemotherapy in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14:47. doi: 10.1186/bcr3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kandioler-Eckersberger D, Ludwig C, Rudas M, Kappel S, Janschek E, Wenzel C, et al. TP53 mutation and p53 overexpression for prediction of response to neoadjuvant treatment in breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:50–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chrisanthar R, Knappskog S, Lokkevik E, Anker G, Ostenstad B, Lundgren S, et al. CHEK2 mutations affecting kinase activity together with mutations in TP53 indicate a functional pathway associated with resistance to epirubicin in primary breast cancer. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3062. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lehmann-Che J, Andre F, Desmedt C, Mazouni C, Giacchetti S, Turpin E, et al. Cyclophosphamide dose intensification may circumvent anthracycline resistance of p53 mutant breast cancers. Oncologist. 2010;15:246–52. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chrisanthar R, Knappskog S, Lokkevik E, Anker G, Ostenstad B, Lundgren S, et al. Predictive and prognostic impact of TP53 mutations and MDM2 promoter genotype in primary breast cancer patients treated with epirubicin or paclitaxel. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19249. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee JM, Bernstein A. p53 mutations increase resistance to ionizing radiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993; 90:5742–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]