Abstract

The symbiotic association between the Hawaiian bobtail squid Euprymna scolopes and the luminous marine bacterium Vibrio fischeri provides a unique opportunity to study epithelial morphogenesis. Shortly after hatching, the squid host harvests bacteria from the seawater using currents created by two elaborate fields of ciliated epithelia on the surface of the juvenile light organ. After light organ colonization, the symbiont population signals the gradual loss of the ciliated epithelia through apoptosis of the cells, which culminates in the complete regression of these tissues. Whereas aspects of this process have been studied at the morphological, biochemical and molecular levels, no in-depth analysis of the cellular events has been reported. Here we describe the cellular structure of the epithelial field and present evidence that the symbiosis-induced regression occurs in two steps. Using confocal microscopic analyses, we observed an initial epithelial remodeling, which serves to disable the function of the harvesting apparatus, followed by a protracted regression involving actin rearrangements and epithelial cell extrusion. We identified a metal-dependent gelatinolytic activity in the symbiont-induced morphogenic epithelial fields, suggesting the involvement of Zn-dependent matrix metalloproteinase(s) (MMP) in light organ morphogenesis. These data show that the bacterial symbionts not only induce apoptosis of the field, but also change the form, function and biochemistry of the cells as part of the morphogenic program.

Keywords: symbiosis, morphogenesis, ciliated epithelia, matrix metalloproteinase

Introduction

The association between the Hawaiian bobtail squid, Euprymna scolopes, and its luminous Gram-negative symbiont, Vibrio fischeri, provides a unique system in which to study developmental morphogenesis. Like all cephalopods, E. scolopes has no true larval stage; hatchlings are miniature adults, and therefore do not undergo a profound developmental metamorphosis (Boletzky, 2003). The ventral surface of the nascent light organ is covered by two elaborate fields of ciliated epithelia. Each field is composed of a base with three pores and two prominent ciliated appendages consisting of an epithelial monolayer separated from a central sinus space by a basement membrane (Fig. 1A) (Montgomery and McFall-Ngai, 1994). Studies of symbiosis onset have shown that these ciliated fields serve as a symbiont-harvesting apparatus; the tips of the appendages oppose in a ring-like formation, and the ciliary motion creates a current to entrain particles entering the mantle cavity during ventilation (Nyholm et al., 2000). Bacteria become suspended above the pores in mucus that is secreted by the epithelial fields, and cells of V. fischeri then migrate through the pores in response to a chitobiose gradient to which they chemotax (Mandel et al., 2012; Kremer et al., 2013). Finally, the cells travel down ducts and into epithelium-lined crypts to colonize the light organ.

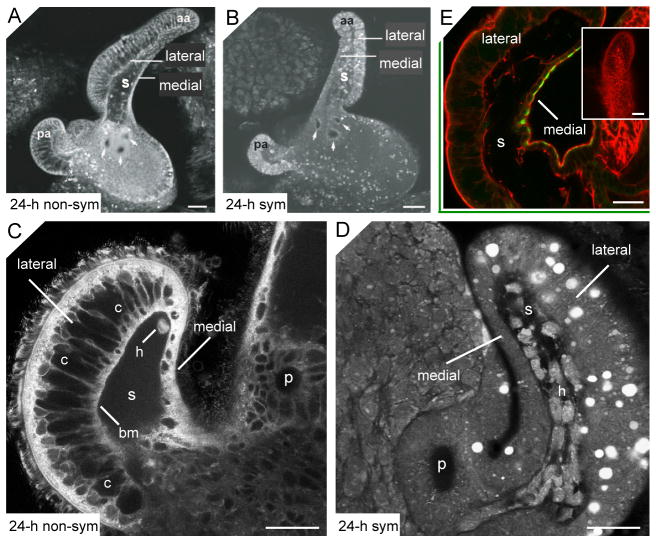

Fig. 1.

Loss of compartments associated with the lateral epithelium monolayer during appendage regression. (A–B) Confocal micrographs show an epithelial field, with anterior (aa) and posterior (pa) ciliated appendages, of a 24-h non-symbiotic light organ (24-h non-sym; A), and a 24-h symbiont-induced morphogenic light organ (24-h sym; B). The epithelial monolayer comprising each appendage has two distinctive morphologies. The medial side, which is continuous with the epithelium of the pores (arrows), is a simple monolayer, while cells of the lateral side form a much thicker epithelial layer. (C–D) Higher magnification confocal micrographs of the tips of anterior appendages illustrate the structure of the lateral and medial monolayers in 24-h non-symbiotic (C) and a 24-h symbiotic (D) light organs. (C) The lateral monolayer of the non-morphogenic appendage contains large compartments (c) separated from the sinus by a basement membrane (bm). A single hemocyte (h) can be seen in the blood sinus. (D) The 24-h morphogenic appendage contains only traces of the compartments. While the sinus space is still evident, it is becoming obscured by infiltrating hemocytes (h); fluorochromes for A–D, acridine orange and LysoTracker Red (see Materials and Methods for details). E) Confocal micrograph of a juvenile light organ showing labeling of the antibody for a squid chitinase (green) on the medial, but not lateral, face of the anterior appendage. Filamentous actin, is stained with rhodamine phalloidin (red). Inset shows an appendage labeled with rabbit IgG alone as a negative control. p, pores; s, sinus. Scale bars, 50 μm.

Approximately 12 h after hatching, at a time when the light organ crypts are fully colonized, the symbiont signals a developmental program that results in the transformation of the juvenile symbiont-harvesting machine into the functional adult light organ (Montgomery and McFall-Ngai 1994; Koropatnick et al., 2004; Troll et al., 2009). The symbiont-harvesting apparatus is completely lost during this developmental program, which begins with the induction of widespread apoptosis (Foster and McFall-Ngai, 1998) and the infiltration of host hemocytes into the sinuses of the epithelial fields (Koropatnick et al., 2007), and culminates in the regression of the ciliated appendages over a period of four days (Montgomery and McFall-Ngai, 1994). A symbiont-derived morphogen is tracheal cytotoxin (TCT), a fragment of the bacterial envelope component, peptidoglycan (PGN), which works in synergy with a second envelope component, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), to trigger a morphogenesis nearly indistinguishable from the developmental program that occurs naturally (Koropatnick et al., 2004).

While the symbiont-induced regression of the ciliated epithelial fields has been the subject of a number of previous studies (reviewed in McFall-Ngai, 2008), many aspects of the cellular and biochemical mechanisms that govern the loss of this elaborate juvenile structure remain largely unknown. Here we investigate the behavior of the cells and underlying actin cytoskeleton of the morphogenic epithelial fields, and present evidence that host-derived matrix metalloproteinase(s) (MMPs) play a role in this developmental process.

Materials and Methods

General Procedures

Adult squid were collected from shallow sand flats of Oahu, Hawaii, and breeding colonies were maintained as previously described (Doino and McFall-Ngai, 1995; Foster et al., 2000). Newly hatched juvenile squid were transferred through three rinses of filter-sterilized seawater (FSW) to prevent premature inoculation with the symbiont. Squid were maintained as non-symbiotic (i.e., non-morphogenic) in FSW, or made symbiotic (i.e., morphogenic) by placing them in FSW containing 5,000 cells per ml V. fischeri strain ES114 (Boettcher and Ruby, 1990). Light organ colonization was monitored by measuring squid luminescence with a photometer (Turner Designs, TD-20/20). Daily water changes were performed in experiments with incubations longer than 24 h.

For assays involving dissections or whole-animal fixations, squid were first anesthetized for 1 min in 2% ethanol in FSW. For the study of epithelial cell extrusion, experiments were also performed in which animals were anesthetized for 1 min by chilling them on ice, or incubating them in 0.37 M MgCl2 in FSW, to control for the potential epithelium-damaging effects of the anesthetic technique. By all anesthetic methods, epithelial sloughing was not observed in non-symbiotic organs, while symbiotic organs had comparable levels of cells undergoing detachment.

For in vitro fluorescence activity assays and in situ zymography, chloramphenicol (30 μg/ml) was added to the FSW at 14 h post-inoculation to eliminate, or cure, the symbiont after the delivery of the 12 h signal for morphogenesis (Doino and McFall-Ngai, 1995). V. fischeri has Zn-dependent metalloproteinases that are used by the symbiont to harvest nutrients from the environment (Fidopiastis, 2001). Although these enzymes are not structurally related to eukaryotic MMPs, they have similar activity (Watanabe, 2004). Curing the light organ of symbionts therefore ensured that the MMP-like activity found in symbiont-induced morphogenic light organs was host-derived.

Chemical reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise stated. Fluorochromes were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA).

Live tissue studies

To examine epithelial fields for evidence of apoptosis, cell sloughing, and ‘vacuole’ loss, live animals were co-stained with 0.001% acridine orange, a fluorochrome that binds nucleic acids, and 0.008% LysoTracker Red, a fluorochrome that labels acidic compartments. Animals were incubated in these vital dyes in FSW for 30 min at room temperature. Ventral dissections were then performed and animals were mounted on glass slides and analyzed using an LSM 510 confocal microscope (Zeiss, New York, NY). Apoptotic cells were identified by their pycnotic nuclei, which label strongly with acridine orange, as previously described (Foster and McFall-Ngai, 1998). Width measurements of the lateral side of anterior appendages were made using differential interference contrast (DIC) images and the LSM 510 version 3.2 software (Zeiss, New York, NY).

Immunocytochemistry (ICC)

A polyclonal antibody to Euprymna scolopes Chitotriosidase 1 (EsChit1) was produced in rabbit (Genscript, Piscataway, NJ) to a unique peptide within the EsChit1 sequence (CYPGSRGSPAVDKKN), chosen for its predicted antigenicity, surface exposure, and lack of similarity to other known, predicted E. scolopes or V. fischeri proteins. Light organs were fixed, permeabilized, and blocked as described previously (Troll et al., 2009). Briefly, the organs were incubated with a 1:1000 dilution of the EsChit1 antibody in blocking solution of 1% goat serum, 1% TritonX-100, and 0.5% bovine serum albumin in marine PBS (mPBS; 50 mM sodium phosphate, 0.45 M sodium chloride, pH 7.4) for 7 d at 4°C, and then rinsed 4 x 1 h in 1% Triton X-100 in mPBS, and incubated overnight in blocking solution at 4°C. Samples were then incubated with a 1:50 dilution of a fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) in blocking solution in the dark at 4°C overnight. The light organs were then counterstained with rhodamine phalloidin as previously described (Troll et al., 2009), mounted on glass slides, and examined on a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope.

Labeling with phalloidin

Animals were processed for labeling with phalloidin as previously reported (Kimbell and McFall-Ngai, 2004). Briefly, juvenile squid were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde in mPBS for 1 h at room temperature. Light organs were then dissected out of the mantle cavity, rinsed in mPBS, and permeabolized using 1% Triton X-100 in mPBS (TX-mPBS) for 20 min. Organs were stained overnight using rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin (2 mg/ml) in TX-mPBS, and then rinsed 3 times for 10 min in mPBS. Stained organs were then mounted on glass slides using Vectashield, a glycerol-based mounting media containing a photo retardant (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and viewed by confocal microscopy.

Microinjection

Juvenile squid were mounted in a solution of 2% gelatin in FSW containing 2% ethanol on a glass slide. The preparations were then cooled on ice until the gelatin solidified, and the mantle and funnel were retracted to reveal the light organ. Fluorescein-conjugated dextran (580,000 Da; 1 mg/ml in mPBS) was injected at a single site in either the central sinus, or the lateral epithelial monolayer in anterior and posterior light organ appendages using a Femtojet microinjection system (Eppendorf, Hauppauge, NY). The preparations were then viewed by confocal microscopy.

In vitro fluorescent substrate assay

Juvenile squids were processed 40 h after hatching. Organs were dissected out of the mantle cavity and maintained on ice in reaction buffer (0.5 M Tris-HCl, 0.15 M NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2, 0.2 mM sodium azide, pH 7.6). Organs were then homogenized on ice using a ground glass mortar and pestle to extract the aqueous soluble fraction. The homogenate was then centrifuged at 20,800 X g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was retained and protein concentration was determined spectrophotometrically (Whitaker and Granum, 1980).

We assessed putative MMP activity using gelatinase activity in organ homogenates with the EnzChek gelatinase assay kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). In this method, the cleavage of the substrate, fluorescein-conjugated DQ-gelatin, results in a fluorescence that is proportional to enzymatic activity. Assays were performed in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions, using 96-well microtiter plates. For light organ and gill homogenates, 40 μg of protein were added to each assay well. For digestive gland homogenates, 20 μg of protein were added per well. Fluorescence output was measured at 30 min intervals for 7 to 14 h using an HTS 7000 plate reader (Perkin Elmer, Wellesley, MA). For each gelatinase assay performed, Clostridium collagenase, a standardized enzyme provided with the EnzCheck kit, was prepared in a similar manner to the sample homogenates using a range of concentrations [0.01 to 0.05 activity units (U)]. For the homogenized squid organ samples, fluorescence/min was plotted against the collagenase standard curve to determine U for each sample, and these values were then divided by the starting quantity of protein to determine the specific activity in U/mg protein.

Proteinase Inhibitors

The metal chelator and general MMP inhibitor 1, 10-phenanthroline (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), and two vertebrate-specific MMP inhibitors, the hydroxamate analogues Z-Pro-Leu-Gly hydroxamate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and Ilomostat (Chemicon international, Temecula, CA) were tested for their ability to inhibit gelatinolytic activity using the fluorescent-substrate assay described above. A protease inhibitor cocktail containing proprietary concentrations of inhibitors with specificity for serine, cysteine, aspartic and aminopeptidases, but no metal-chelating agents that would inhibit MMPs (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), was also tested to determine levels of non-MMP gelatinolytic activity.

Initial assays were performed to determine the concentration of effective inhibition of Clostridium collagenase (0.03 U/ml) and/or Proteinase K (0.01 μg/ml). For these initial screens, at least three, 10-fold dilutions were tested that included concentrations previously found to be effective at inhibiting various invertebrate MMPs (Leontovich et al., 2000; Quinones et al., 2002; Ziegler et al., 2002). To ensure the validity of this screening process, 1,10-phenanthroline was tested using the same dilution series on morphogenic light organ homogenates, and the concentration that induced maximum inhibition was determined to be identical to the effective concentration determined by the Clostridium collagenase control assay. The protease inhibitor cocktail (10-fold dilution), 1,10-phenanthroline (1 mM), Z-Pro-Leu-Gly hydroxamate (10 mM) and Ilomostat (50 μM) were then tested on squid organ homogenates.

The general MMP inhibitor 1, 10-phenanthroline was also prepared in FSW to test its effects on light organ morphogenesis in living juvenile squid. Initial LD50 assays were performed using a 10-fold serial dilution (from 1 mM to 1 μM). Animals were incubated in 1, 10-phenanthroline (1 μM) for three days, and cohorts were processed at 48 h and 72 h for regression analysis as previously described (Doino and McFall-Ngai, 1995; Koropatnick et al., 2004).

In situ zymography

Gelatinolytic activity was localized in unfixed cryostat sections (10 μm thick) using an established technique (Mook et al., 2003). Specifically, light organs were dissected out of juvenile squid 40 h after hatching, mounted using HistoPrep mounting media (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) and sectioned using a Histostat cryostat (American Optical, New York, NY). Sections were air-dried on glass slides for 10 min, and then incubated for 15 min in reaction buffer (0.5 M Tris-HCl, 0.15 M NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2, 0.2 mM sodium azide, pH 7.6). After pre-incubation, the reaction buffer was wicked off the slide using tissue paper. DQ-gelatin substrate (Enz-Chek; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was dissolved in distilled water (1 mg/ml) and diluted 10-fold in reaction buffer containing low gelling temperature agarose (1% w/v) and propidium iodide (0.5 μg/ml), which served as a counter-stain for nuclei. Sections were coated with this agarose mixture, and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 45 min.

The metal-dependent gelatinolytic activity was identified by pre-incubating sections with the 1, 10-phenanthroline (1.0 mM) in reaction buffer for 15 min. Sections were then wicked dry using tissue paper, coated in DQ-gelatin mixture containing 1, 10-phenanthroline (1.0 mM), and incubated as described above.

Sections were viewed using an Axioskop 2 fluorescence microscope (Zeiss, New York, NY) and images were captured using an Optronics Macrofire digital camera (JH Technologies, San Jose, CA) and Picture Frame 2.1 software. After image acquisition, background subtractions and 2-D blind deconvolutions were performed using AutoDeblur version 9.3 (AutoQuant Imaging, Watervliet, NY).

Results

Epithelial field asymmetry and symbiosis-induced remodeling

The epithelial monolayer that forms the appendages of the light organ is a heterogeneous sheet of cells, both anatomically and biochemically (Fig. 1). The medial side of each appendage, which is continuous with the epithelium of the pores, is a thin monolayer. In contrast, the lateral side of each appendage is a much thicker structure containing large compartmental spaces separated by thin septa (Fig. 1C). Epithelial cell nuclei occur in either a medial or apical location within this monolayer, but the bulk of the monolayer derives from the compartments. These spaces began to disappear from the lateral appendage epithelium of symbiotic organs as early as 18 to 24 h post-inoculation (Fig. 1D). By 36 to 48 h, no evidence of the spaces remained, and the medial and lateral sides of the appendages were no longer easily distinguishable. Further, we also provide evidence for a biochemical asymmetry in the two regions of the appendage. In a recent study, we found that a chitinase, which labels with antibody at the apical surfaces of all cells of the appendage, is important for early events of the symbiosis (Kremer et al., 2013). In studying this family of chitinases in the host, we found another member of the family that labels with antibody only in the medial cells of the appendage (Fig. 1E).

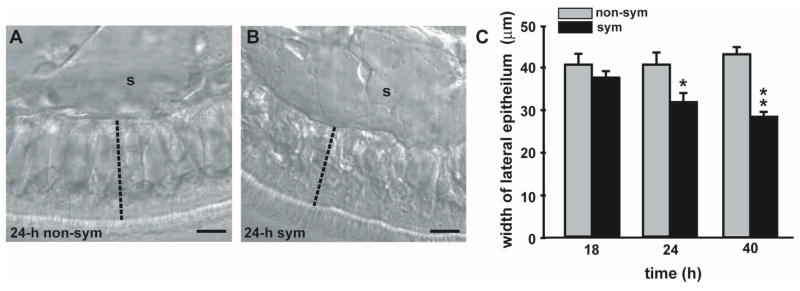

The loss of these compartments corresponded to a significant reduction in the width of the lateral appendage monolayer (Fig. 2). This width reduction is first evident at 24 h when the structures are reduced but still detectable in the lateral epithelium of morphogenic appendages (Fig. 2C). Width reduction is more pronounced by 40 h, when the compartments are no longer present in morphogenic appendages.

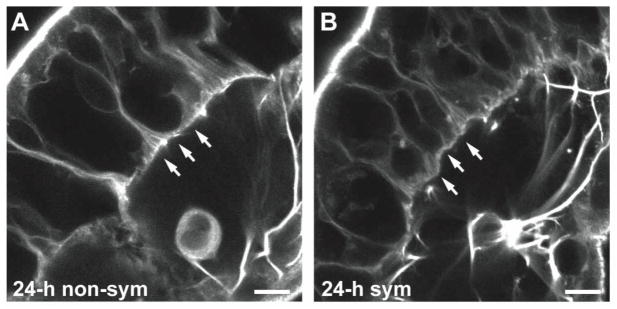

Fig. 2.

Changes in the width of the lateral epithelium of the appendage during morphogenesis. (A–B) DIC images of the lateral epithelial monolayer of a 24-h non-symbiotic (24-h non-sym; A) and a 24-h symbiotic (24-h sym; B) light organ appendage. The width was gauged by measuring reference lines drawn across the lateral epithelium perpendicular to the basement membrane (dashed line). s, sinus. Scale bar, 15 μm. (C) Quantification of changes in width of the lateral epithelium during the early hours of symbiosis. Non-symbiotic and symbiotic organ appendages were measured at 18 h, 24 h, and 40 h. Data are representative means +/− S.E.M. for 1 of 3 replicates for each time point (n = 8–11 animals per treatment). * indicates significance, P<0.05 difference compared to non-sym. ** indicates significance, P<0.001 difference compared to non-sym.

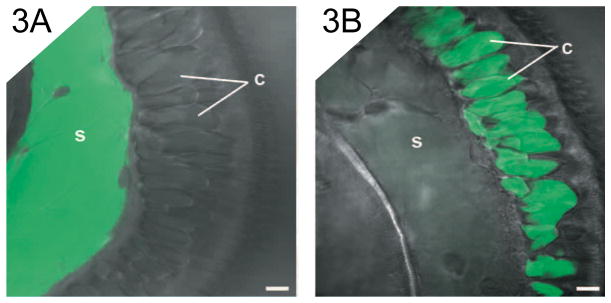

While the precise function and contents of these large spaces is unclear, some evidence suggests that they may be extracellular. During the early hours of epithelial morphogenesis, living hemocytes have been observed within these compartments (Koropatnick et al., 2007). In addition, the microinjection of FITC (fluorescein isothiocyanate) dextran (580,000 Daltons) into a single compartment resulted in the consecutive filling of neighboring compartments along the length of the appendage, while the septa separating each compartment remain intact (Fig. 3). Given that intracellular gap junctions allow passage of molecules less than 1,100 Daltons in size (Loewenstein, 1966), the channels connecting these compartments are much too large to mediate intracellular transport. These data suggest that the compartmental spaces are extracellular.

Fig. 3.

Features of the compartments associated with the lateral appendage epithelium. Confocal micrographs superimposed over DIC images of non-morphogenic anterior appendages. Appendages were microinjected at a single site with fluorescent dextran. (A) An appendage with dextran injected into the central sinus (s). (B) An appendage with dextran injected into a compartment (c) in the lateral epithelium. Scale bar, 10 μm.

When dextran was injected into the compartmental region of the lateral monolayer, only trace amounts could be seen within the appendage sinus, and conversely, the sinus region could also be injected with FITC dextran without filling the compartments within the lateral monolayer (Fig. 3). These data suggest that the compartments and the sinus are distinct and separate spaces within the appendage.

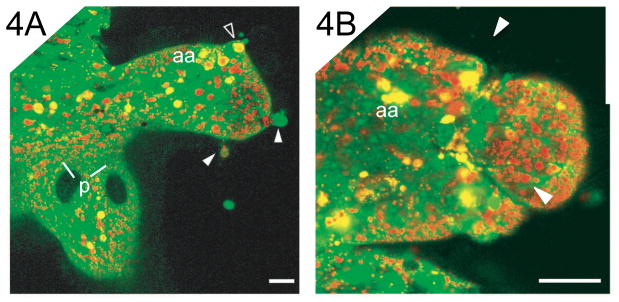

The fate of cells of the regressing epithelial field

We examined the appendages of living symbiotic organs at intervals during the most rapid period of epithelial morphogenesis, between 12 h and 60 h post-inoculation with the symbiont. By approximately 18 h, the epithelial monolayer of the ciliated fields had become disrupted as both individuals and groups of cells detached and sloughed into the mantle cavity (Fig. 4). Cell detachment continued in a random fashion over time as the appendages shortened. Detachment was not limited to apoptotic cells; living cells with actively beating cilia were also observed detaching and ‘swimming’ away into the mantle space.

Fig. 4.

Cell detachment during epithelial morphogenesis. Confocal micrographs of morphogenic epithelial fields of symbiotic light organs labeled with acridine orange, a fluorescent dye that binds nucleic acids and highlights the condensed chromatin of the pycnotic nuclei of the apoptotic cells (yellow foci) and LysoTracker Red (see Materials and Methods for details). (A) Living cells (solid arrowheads) and an apoptotic cell (open arrowhead) can be seen detaching from the epithelial monolayer of a posterior appendage. (B) A group of cells can be seen in the process of detachment by constriction of the region (arrows) at the tip of a posterior appendage. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Actin cytoskeletal rearrangements

When viewed at the apical surface, F-actin labeled (rhodamine phalloidin) epithelial cells of non-morphogenic appendages were shaped like flat tiles; the epithelium was uniform in appearance and each cell contained a distinctive peripheral band of actin adjacent to the apical cell border (Fig. 5A). In contrast, symbiont-induced morphogenic appendages often contained regions of irregularity, where apical bands of peripheral actin were less distinct, cells appeared rounded, and frequent gaps disrupted the uniformity of the monolayer (Fig. 5B). These obvious gaps in the apical surface of the epithelial monolayer were created by the process of cell detachment and sloughing into the mantle cavity (Fig. 5C). Optical sections through phalloidin-labeled epithelia at sites of active cell extrusion revealed that actin-rich processes extended from adjacent cells to maintain contact with the detaching cell (Fig. 5D). Later in this process of detachment, epithelial cells adjacent and basal to the extrusion event became juxtaposed and distinct F-actin bands bordered the gap created by the detaching cell (Fig. 5E). Thus the integrity of the appendage sinus appeared uncompromised throughout the extrusion process.

Fig. 5.

Apical actin cytoskeleton rearrangements during epithelial morphogenesis. Confocal micrographs of 48-h light organs labeled with rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin show the actin cytoskeleton within cells of the epithelial fields. (A–C) 3-dimensional reconstructions of optical sections show apical surface projections of anterior appendages. (A) A non-morphogenic appendage is a uniform monolayer with cells containing distinctive peripheral cytoskeletons. (B–C) Cells of morphogenic appendages appear rounded with less distinct actin bands. Obvious gaps appear on the apical surface. (C) The tip of an appendage shows a cell in the process of detachment (solid arrowhead). (D, E) Single optical sections through morphogenic appendages show concentrated bands of actin in neighboring cells bordering the site of cell detachment. Open arrowheads, cells detaching. (D) Early in a detachment event, adjacent cells contain concentrated bands of actin (arrows) at remaining sites of contact with the departing cell. (E) As a cell rounds up before extrusion, concentrated actin bands are visible in adjacent cells at the border basal to the detachment event. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Cells of the epithelial monolayer also showed evidence of actin cytoskeletal rearrangements at the site of attachment to the basement membrane (Fig. 6). In epithelial cells of non-morphogenic appendages, the actin cytoskeleton formed peripheral fiber bundles that bordered the basal cell membrane in a relatively straight band (Fig. 6A). In 24-h symbiotic organs, these peripheral actin fibers formed a less dense, jagged line along the basal membrane. (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Basal actin cytoskeletal rearrangements during epithelial morphogenesis. Confocal micrographs of light organs labeled with rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin show the actin fibers bordering the basal site of epithelial cell attachment to the basement membrane (arrows) in a non-symbiotic (non-sym) organ appendage (A), and a symbiotic (sym) organ appendage (B) at 24 h post-inoculation. Scale bar, 10 μm.

The sinus spaces of both non-morphogenic and morphogenic appendages contained numerous actin filaments spiraling longitudinally from base to tip (Fig. 7). As epithelial regression proceeded, the transverse fibers spanning the width of the sinus became more apparent; however both longitudinal and transverse fibers were still visible at 48-h, the most advanced stage of regression analyzed for changes in F-actin.

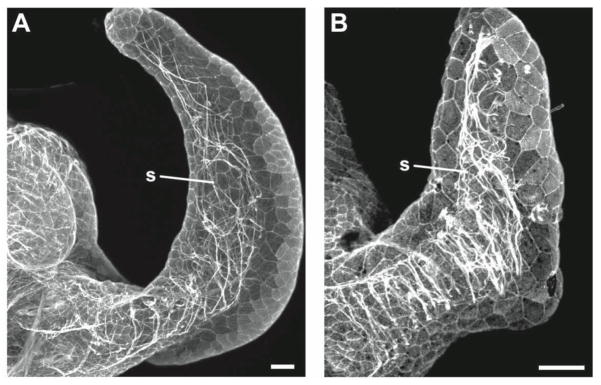

Fig. 7.

Appendage sinuses contain numerous actin fibers with different orientations and densities in non-symbiotic and symbiotic animals. Three-dimensional reconstructions of optical sections through phalloidin-labeled anterior appendages show F-actin within appendage sinuses. (A) Actin fibers run haphazardly along the length of the sinus in this non-morphogenic appendage of a non-symbiotic animal. (B) In the appendage of a symbiotic animal undergoing morphogenesis, actin filaments are visible spanning the sinus in a transverse orientation. Scale bar, 20 μm.

In vitro gelatinase activity

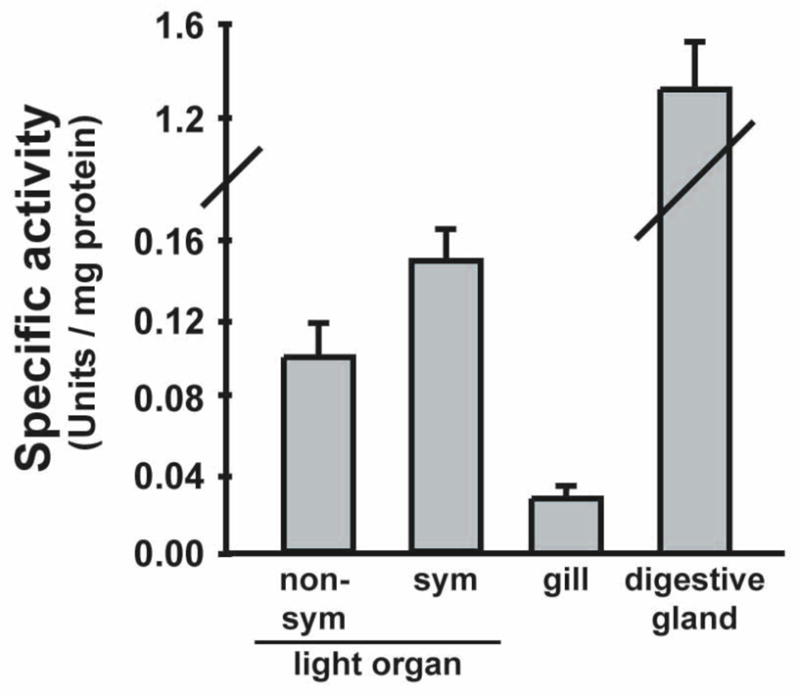

Matrix metalloproteinases have been implicated in epithelial cell-basement membrane interactions during tissue remodeling in other systems (Werb and Chin, 1998). In the squid-vibrio system, the transcription of genes encoding these proteins is up-regulated with symbiosis onset (Chun et al., 2008), and an MMP is differentially regulated in the hemocytes of symbiotic and non-symbiotic adult squid (Collins et al., 2012). Thus, we chose to investigate a possible role for MMPs in light organ morphogenesis. We used a fluorometric assay to quantify gelatinase activity in light organ homogenates from juvenile E. scolopes (Fig. 8). Morphogenic light organs contained 1.5 – 2 fold more gelatinase activity in comparison with non-morphogenic light organs, although this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.099, two sample T-Test). The maximum activity detected in morphogenic light organs was 0.18 U/mg. To establish the relevance of this level of gelatinolytic activity, several control tissues were isolated from symbiont-induced morphogenic animals and assayed for activity. The gills are non-symbiotic, non-morphogenic epithelial organs that contain high numbers of hemocytes and therefore allow the determination of hemocyte and epithelial cell activity levels outside of the light organ. Digestive glands, the source of digestive enzymes, served as a positive control for gelatinolytic activity. Gelatinase activity was detected in gills at levels that were 4-fold lower than those found in morphogenic light organs, while digestive gland activity peaked at 10-fold higher than morphogenic light organ levels.

Fig. 8.

In vitro gelatinolytic activity in squid tissues was quantified using a fluorometric assay. Juvenile non-symbiotic (non-sym) and symbiotic (sym) animals were treated with antibiotics at 14 h to eliminate cells of V. fischeri in symbiotic light organs. At 40 h, organs were homogenized and the soluble protein fraction was incubated with fluorescein-gelatin substrate. The rate of fluorescence output was compared to control collagenase to determine the specific enzyme activity for each tissue. Gill and digestive glands were isolated from antibiotic-cured symbiotic animals. Data are means +/− SEM for 4 replicate experiments for light organs and 2 replicate experiments for gill and digestive glands.

Proteinase inhibitors

As gelatin is easily digested by many enzymes, the source of the gelatinase activity found in squid tissues was evaluated using specific enzyme inhibitors (Table 1). The gelatinase activity detected in morphogenic light organ homogenates was largely eliminated by the addition of the potent metal chelator and general MMP inhibitor, 1,10-phenanthroline. Digestive gland activity was also reduced almost completely by this inhibitor, demonstrating the presence of metal ion-dependent gelatinases in digestive tissues. Light organ activity was much less affected by the peptide-hydroxamate analogues, Ilomostat, and Z-Pro-Leu-Gly hydroxamate, which are inhibitors designed to target the active site of mammalian MMPs. Enzyme activity was virtually unaffected when light organ homogenates were incubated with a protease inhibitor cocktail containing inhibitors specific to serine, cysteine, aspartic, and aminopeptidases, but no MMP inhibitors; however this cocktail markedly reduced the gelatinase activity of digestive gland homogenates.

Table 1.

Effects of proteinase inhibitors on gelatinolytic activity detected in vitro.

| Inhibitor type | Reagent | Organ1 | % Remaining activity (± SE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MMP | 1, 10-Phenanthrolinc (1 mM) | Light organ | |

| symbiotic 3 | 15 ± 1 | ||

| non-symbiotic 3 | 22 ± 4 | ||

| Digestive gland 2,3 | 3 ± 1 | ||

| Z-Pro-Leu-Gly hydroxamate (10 mM) | Light organ 2,5 | 77 ± 4 | |

| GM6001 (Ilomostat) (50 mM) | Light organ 2,5 | 83 ± 6 | |

|

| |||

| Non-MMP | Protease inhibitor cocktail (1:10) | Light organ 2,4 | 96 ± 3 |

| Digestive gland 2,4 | 61 ± 6 | ||

All organs were isolated from 40-h animals that had been treated with antibiotics at 14-h to eliminate the symbionts

Organs were isolated from antibiotic-cured symbiotic animals

n = 4 replicate assays

n = 2 replicate assays

n = 3 replicate assays

We attempted in vivo assays to determine whether or not the most effective inhibitor of in vitro gelatinase activity, 1,10-phenanthroline, could interfere with epithelia regression, thereby implicating an MMP-like activity in the process of morphogenesis. Unfortunately, the concentrations determined to be effective in vitro on squid tissue homogenates were highly toxic to living squid when diluted in the ambient seawater. Specifically, 1,10-phenanthroline was lethal at concentrations down to 10 μM after an exposure of only 30 min. This lethal dose was 100-fold more dilute than the concentration used to inhibit squid gelatinase activity in vitro, and 200-fold more dilute than the concentration used to inhibit in vivo MMP activity in the sea cucumber (Quinones et al., 2002). Animals incubated in a sub-lethal dose of 1,10-phenanthroline (1 μM) showed no signs of toxicity and no alterations in the symbiont-induced morphogenic pattern by either 48-h or 72-h of exposure (data not shown).

In situ gelatinase activity

Because homogenization was necessary for the in vitro analysis of MMP activity, spatial localization of gelatinase activity was precluded. In addition, because MMPs are regulated at the protein level by the proteolytic cleavage of the prodomain for activation, and by the endogenous tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs), the act of homogenization may have artificially brought MMP zymogens in contact with activating enzymes and/or inhibitors, thus producing a false gelatinase signature in the homogenates (Galis et al., 1995; Mook et al., 2003).

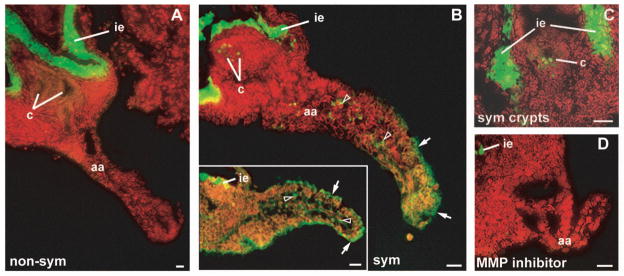

We used in situ zymography to detect gelatinase activity within light organ sections (Fig. 9). This technique limits the disruption of tissue structure and thus provides a snapshot of the spatial distribution of ‘real’ gelatinase activity within the organs. Both morphogenic and non-morphogenic organs had gelatinase activity within the lining of the ink sac. However, only symbiotic light organs showed activity in the appendage epithelium and in punctate spots within the appendage sinus (Fig. 9B), which, by 40 h, should be filled with host hemocytes (Koropatnick et al., 2007). Gelatinase activity was also observed within the region of the crypts in morphogenic light organs (Fig. 9C). This activity is likely host-derived, as squid were treated with antibiotics to cure the crypts of cells of V. fischeri 24 h before the zymography was performed. Gelatinase activity in morphogenic organ appendages and crypts was eliminated when sections were incubated with the metal chelator, 1,10-phenanthroline; however the activity in the epithelium surrounding the ink sac remained (Fig. 9D).

Fig. 9.

In situ gelatinolytic activity in cryosectioned light organs. Juvenile non-symbiotic (non-sym) and symbiotic (sym) animals were treated with antibiotics at 14 h to eliminate cells of V. fischeri from symbiotic light organs. Organs were sectioned at 40 h post hatching and incubated with fluorescein-gelatin substrate, which fluoresces after proteolytic cleavage (green). Nuclei were counterstained with propidium iodide (red). (A) A non-symbiotic organ has a bright band of gelatinase activity in the region of the ink sac epithelium (ie). (B) Symbiont-induced morphogenic organs also have activity associated with the morphogenic appendage epithelium (arrows) and cells within the appendage sinus (open arrowheads; B and inset). (C) Gelatinase activity was also detected in the region of the crypts in symbiotic organs. (D) The appendage and crypt activity was eliminated when symbiotic organs were incubated with the general MMP inhibitor 1,10-phenanthroline, but the activity associated with the ink sac epithelium was not affect by this treatment. aa, anterior appendage; c, crypts; ie, ink sac epithelium. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Discussion

This work, which builds upon the previous studies of light-organ morphogenesis, investigates the cellular mechanisms by which the elaborate ciliated fields of the juvenile organ are lost following symbiosis onset. Specifically, this study identifies 2 stages of disassembly of the epithelial fields: 1) the lateral epithelia narrow with the loss of their basal compartments; and, 2) the appendages shorten through the detachment and sloughing of cells into the mantle cavity through a process that involves actin cytoskeletal rearrangements. Further, evidence is presented for the involvement of MMP-like enzymes as mediators of the disassembly process.

Epithelial remodeling

The disappearance of large compartments associated with the lateral portions of appendage epithelium correlated with a reduction in appendage width. Although previously interpreted as intracellular vacuoles (Foster and McFall-Ngai, 1998), the data presented here suggest that these structures are extracellular compartments. While the nature of these compartments is unclear, we propose that they may serve a structural function as a hydrostatic skeleton, providing shape and support for the ‘ring’ formation held by the appendages during symbiotic inoculation. After light organ colonization, this harvesting apparatus is no longer needed, thus the loss of the compartments may provide a relatively rapid mechanism for disabling this apparatus. Previous work on the system had showed that colonization of the crypts by V. fischeri also causes a cessation of harvesting-associated mucus shedding from the surface epithelium, which provides further evidence for symbiont-induced disabling of these tissues (Nyholm et al., 2002). This initial ‘off switch’ is then followed by the more gradual destruction of the ciliated fields over 4 days. F-actin staining has revealed that the sinuses contain numerous actin filaments that span the entire length and width of the light organ appendages, in a manner suggestive of muscle fibers (Fig. 7). While muscle cells have not been explicitly identified within these appendages, these fibers may act on the hydrostatic skeleton of the appendages and exert a force, as is necessary to create movement and shape changes in any skeletal system (Alexander, 1983).

Mechanisms underlying regression of the ciliated epithelium

The loss of the ciliated field appears to be tightly controlled. As in other systems, external epithelia of an animal form a barrier between the body and the environment (Fristrom, 1988). It follows that, during normal developmental remodeling of this protective layer, barrier function is carefully maintained as cells are turned over. Conversely, microbe-derived ‘toxins’ trigger epithelial remodeling in pathogenesis, resulting in cell damage and breaches of this protective barrier (Berkes et al., 2003). Although the symbiont-induced morphogenesis of the squid light organ is triggered by two bacterial ‘toxins’, LPS (i.e., endotoxin) and TCT (i.e., tracheal cytotoxin) (Koropatnick et al., 2004), the regression of the epithelial appendages does not appear to result from tissue damage, but rather from a series of controlled cell movements that preserve barrier integrity.

Both individuals and groups of living and apoptotic epithelial cells detached from the ciliated epithelial fields and sloughed into the mantle cavity during light organ morphogenesis. Although an apical view of a detachment event suggests that disruption of barrier function must occur due to the loss of continuity of the epithelial monolayer, the integrity of the monolayer appears intact due to the maintenance of cell-cell contacts by epithelial cells adjacent and basal to the extruding cell. Likewise, studies of vertebrate epithelial integrity have shown that barrier function is carefully maintained during cell extrusion associated with normal tissue remodeling (Madara, 1990; Rosenblatt et al., 2001). For example, in the epithelium lining the mammalian small intestine, epithelial cells become rounded at their apex and detach as individuals and in groups at the tips of absorptive villi (Leblond, 1981; Mayhew et al., 1999). The integrity of the epithelial barrier is maintained during this normal process of cell turn-over due to the actions of adjacent enterocytes, which extend cell processes along the lateral borders and under the basal pole of the extruding cell, resulting in the migration of tight junctions (Madara, 1990).

Previous work described the symbiont-induced increase in actin protein abundance accompanied by cell shape changes in the epithelium lining the ducts of newly colonized squid light organs (Kimbell and McFall-Ngai, 2004). In the present study, symbiont-induced actin rearrangements were examined in cells of the epithelial fields covering the ventral surface of the light organ. Epithelial cells of morphogenic appendages lost the distinctive peripheral bands of actin that defined the apical cell borders in non-morphogenic epithelial fields. These apical perijunctional rings are associated with sites of cell-cell contacts at adherens junctions in both invertebrate and vertebrate epithelia (Fristom, 1988; Turner, 2000). Cytoskeletal rearrangements were also observed at the basal site of attachment to the underlying basement membrane in morphogenic appendage epithelia. The disappearance of the distinctive actin framework at both apical and basal sites of cell anchorage may be indicative of the disruption of cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesion that must precede cell detachment.

In mammals, epithelial morphogenesis involves the MMP-mediated breakdown of cell-cell and cell-matrix anchors, resulting in tissue restructuring, cytoskeletal reorganization, cell shape changes, and cell detachment (for reviews see Werb and Chin, 1998; Schock and Perrimon, 2002). A metal-dependent gelatinase activity was detected in morphogenic light organs. Specifically, this MMP-like activity localized to the epithelium and the sinus spaces of morphogenic epithelial fields. By 40 h, the sinuses of morphogenic appendages are filled with hemocytes, thus both epithelial cells and hemocytes may contribute to the gelatinolytic activity found in morphogenic light organs.

While morphogenic organ homogenates had 1.5 – 2 fold higher gelatinolytic activity than non-morphogenic organs using the in vitro fluorescent substrate assay, this difference was not statistically significant. The metal chelator 1,10-phenanthroline was sufficient to eliminate all but a fraction of the gelatinase activity found in morphogenic and non-morphogenic light organs (Table 1), suggesting that a metal dependent gelatinase contributed the majority of activity detectable in both conditions. By in situ zymography, the activity common to both morphogenic and non-morphogenic light organs localized to the lining of the ink sac; this region was the only site of activity detectable in non-morphogenic light organs using this method. However, this gelatinolytic activity was not metal-dependent, as it was not inhibited by 1,10-phenanthroline. These data suggest that non-morphogenic organs contained a metal-dependent gelatinolytic activity that was detectable in vitro using light organ homogenates, but was not detectable by in situ zymography. This discrepancy could be explained by considering that cells of non-morphogenic organs may maintain a standing stock of MMP zymogen ready for release in response to the morphogenic signal. The tissue homogenization required for the in vitro assays would liberate these zymogen stores, which would then be activated by other non-specific proteases. During in situ zymography these zymogens would remain separated from activating enzymes, as the tissue remains relatively intact using this method (Galis et al., 1995; Mook et al., 2003).

Host-derived gelatinase activity was also detected in the region of the crypts in symbiotic organs that had been cured of their symbionts. This activity may be related to cell sloughing events previously observed in the deep crypts of light organs of adult E. scolopes as part of a diel cycle of epithelial renewal (Nyholm and McFall-Ngai, 1998; Wier et al., 2010).

While 1,10-phenanthroline dramatically reduced gelatinase activity in vitro and completely eliminated the activity in light organ appendages in situ, more specific inhibitors of vertebrate MMPs, the peptide-hydroxamate analogues Ilomostat and Z-Pro-Leu-Gly hydroxamate, had only minor effects (Table 1). Although hydroxamates are potent inhibitors of several invertebrate and plant MMPs (Delorme et al., 2000; Leontovich et al., 2000; Quinones et al., 2002), other studies of molluscan MMP-like activity have found them ineffective, while 1,10-phenanthroline is strongly inhibitory (Mannello et al., 1998; Ziegler et al., 2002). However, given that 1,10-phenanthroline is a general metal ion-chelator, caution must be used in the interpretation of the enzyme activity data reported here. At present, the most we can conclude is that a metal ion-dependent gelatinase activity (i.e., an MMP-like activity) localizes to the morphogenic epithelial fields. Further speculation regarding the identity of the gelatinase awaits the localization of MMPs specific to E. scolopes within morphogenic light organs.

Conclusion

Although we have investigated the cellular basis of light organ morphogenesis in the squid-vibrio system, much remains to be determined. The bacterial envelope component TCT, a monomer of PGN, is the symbiont-derived signal factor that works synergistically with LPS to trigger the near complete regression of the epithelial fields (Koropatnick et al., 2004). Because TCT and LPS have been found to be potent inducers of MMP production in models of pathogenesis (Ikeda and Funaba, 2003; Lai et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2004), we speculate that the mechanism for TCT/LPS-induced epithelial regression involves the activity of host-derived MMPs. However, how the TCT and LPS signal, which the symbiont presents directly to the crypt epithelia, makes its way to the superficial ciliated fields remains to be determined. Thus, further investigations are needed to localize host receptors for these morphogenic factors, and to identify the pathway of signal transduction responsible for the delivery of the morphogenic message to the site of epithelial morphogenesis. Using the experimentally tractable squid-vibrio symbiosis, we hope to shed light on aspects of symbiosis-induced host development in animals.

Abbreviations

- DIC

differential interference contrast

- F-actin

filamentous actin

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- FSW

filter-sterilized seawater

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase(s)

- mPBS

marine phosphate buffered saline

- PGN

peptidoglycan

- TCT

tracheal cytotoxin

- TIMPs

tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases

- TX

Triton-X

Literature Cited

- Alexander RM. Animal mechanics. Blackwell Scientific; Oxford: 1983. Pressure, density and surface tension; pp. 152–182. [Google Scholar]

- Berkes J, V, Viswanathan K, Savkovic SD, Hecht G. Intestinal epithelial responses to enteric pathogens: effects on the tight junction barrier, ion transport, and inflammation. Gut. 2003;52:439–451. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.3.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boettcher KJ, Ruby EG. Depressed light emission by symbiotic Vibrio fischeri of the sepiolid squid Euprymna scolopes. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3701–3706. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.7.3701-3706.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boletzky Sv. Biology of early life stages in cephalopod molluscs. Adv Mar Biol. 2003;44:143–203. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2881(03)44003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun CK, Troll JV, Koroleva I, Brown B, Manzella L, Snir E, et al. Effects of colonization, luminescence, and autoinducer on host transcription during development of the squid-vibrio association. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:11323–11328. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802369105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins AJ, Schleicher TR, Rader BA, Nyholm SV. Understanding the role of host hemocytes in a squid/vibrio symbiosis using transcriptomics and proteomics. Front Immunol. 2012;3:91. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00091. (eCollection 2012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delorme VGR, McCabe PF, Kim DJ, Leaver CJ. A matrix metalloproteinase gene is expressed at the boundary of senescence and programmed cell death in cucumber. Plant Physiol. 2000;123:917–927. doi: 10.1104/pp.123.3.917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doino JA, McFall-Ngai MJ. Transient exposure to competent bacteria initiates symbiosis-specific squid light organ morphogenesis. Biol Bull. 1995;189:347–355. doi: 10.2307/1542152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidopiastis PM. PhD Dissertation. University of Hawaii; Honolulu: 2001. Benign infection of sepiolid squids by luminous vibrio species: model systems for understanding environmental and genetic factors that regulate bacteria-host interactions. [Google Scholar]

- Foster JS, McFall-Ngai MJ. Induction of apoptosis by cooperative bacteria in the morphogenesis of host epithelial tissues. Dev Genes Evol. 1998;208:295–303. doi: 10.1007/s004270050185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster JS, Apicella MA, McFall-Ngai MJ. Vibrio fischeri lipopolysaccharide induces developmental apoptosis, but not complete morphogenesis, of the Euprymna scolopes symbiotic light organ. Dev Biol. 2000;226:242–254. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fristrom D. The cellular basis of epithelial morphogenesis. A review. Tissue and Cell. 1998;5:645–690. doi: 10.1016/0040-8166(88)90015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galis ZS, Sukhova GK, Libby P. Microscopic localization of active proteases by in situ zymography: detection of matrix metalloproteinase activity in vascular tissue. Fed Amer Soc Exp Biol. 1995;9:974–980. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.10.7615167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda T, Funaba M. Altered function of murine mast cells in response to lipopolysaccharide and peptidoglycan. Immunol Lett. 2003;88:21–26. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(03)00031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimbell JR, McFall-Ngai MJ. Symbiont-induced changes in host actin during the onset of a beneficial animal-bacterial association. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:1434–1441. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.3.1434-1441.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koropatnick TA, Engle JT, Apicella MA, Stabb EV, Goldman WE, McFall-Ngai MJ. Microbial factor-mediated development in a host-bacterial mutualism. Science. 2004;306:1186–1188. doi: 10.1126/science.1102218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koropatnick TA, Kimbell JR, McFall-Ngai MJ. Responses of host hemocytes during the initiation of the squid-vibrio symbiosis. Biol Bull. 2007;212:29–39. doi: 10.2307/25066578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer N, Philipp EER, Carpentier M-C, Brennan CA, Kraemer L, Altura MA, et al. Initial symbiont contact orchestrates host organ-wide transcriptional changes that prime tissue colonization. Cell Host & Microbe. 2013;14:183–194. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai WC, Zhou M, Shankavaram U, Peng G, Wahl LM. Differential regulation of lipopolysaccharide-induced monocyte matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-1 and MMP-9 by p38 and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Immunol. 2003;170:6244–6249. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.12.6244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leblond CP. The life history of cells in renewing systems. J Anat. 1981;160:113–158. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001600202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leontovich AA, Zhang J, Shimokawa K, Nagase H, Sarras MP., Jr A novel hydra matrix metalloproteinase (HMMP) functions in extracellular matrix degradation, morphogenesis, and the maintenance of differentiated cells in the foot process. Development. 2000;127:907–920. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.4.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein WR. Permeability of membrane junctions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1996;137:441–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1966.tb50175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madara JL. Maintenance of the macromolecular barrier at cell extrusion sites in intestinal epithelium: physiological rearrangement of tight junctions. J Memb Biol. 1990;116:177–184. doi: 10.1007/BF01868675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel MJ, Schaefer AL, Brennan CA, Heath-Heckman EA, Deloney-Marino CR, McFall-Ngai MJ, et al. Squid-derived chitin oligosaccharides are a chemotactic signal during colonization by Vibrio fischeri. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:4620–4626. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00377-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannello F, Canesi L, Gazzanelli G, Gallo G. Biochemical properties of metalloproteinases from the hemolymph of the mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis Lam. Comp Biochem Physiol B. 2001;128:507–515. doi: 10.1016/s1096-4959(00)00352-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayhew TM, Myklebust R, Whybrow A, Jenkins R. Epithelial integrity, cell death and cell loss in mammalian small intestines. Histol Histopathol. 1999;14:257–267. doi: 10.14670/HH-14.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFall-Ngai M. Host-microbe symbiosis: the squid-vibrio association - a naturally occurring, experimental model of animal/bacterial partnerships. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;635:102–112. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-09550-9_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery MK, McFall-Ngai M. Bacterial symbionts induce host organ morphogenesis during early postembryonic development of the squid Euprymna scolopes. Development. 1994;120:1719–1729. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.7.1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mook ORF, Van Overbeek C, Ackema EG, Van Maldegem F, Frederiks WM. In situ localization of gelatinolytic activity in the extracellular matrix of metastases of colon cancer in rat liver using quenched fluorogenic DQ-gelatin. J Histochem Cytochem. 2003;51:821–829. doi: 10.1177/002215540305100613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyholm SV, McFall-Ngai MJ. Sampling the light organ microenvironment of Euprymna scolopes: Description of a population of host cells in association with symbiont Vibrio fischeri. Biol Bull. 1998;195:89–97. doi: 10.2307/1542815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyholm SV, Stabb EV, Ruby EG, McFall-Ngai MJ. Establishment of an animal-bacterial association: recruiting symbiotic vibrios from the environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:10231–10235. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.18.10231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyholm SV, Deplancke B, Gaskins HR, Apicella MA, McFall-Ngai MJ. Roles of Vibrio fischeri and nonsymbiotic bacteria in the dynamics of mucus secretion during symbiont colonization of the Euprymna scolopes light organ. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:5113–5122. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.10.5113-5122.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinones JL, Rosa R, Ruiz DL, Garcia-Arraras JE. Extracellular matrix remodeling and metalloproteinase involvement during intestine regeneration in the sea cucumber Holothuria glaberrima. Dev Biol. 2002;250:181–197. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt J, Raff MC, Cramer LP. An epithelial cell destined for apoptosis signals its neighbors to extrude it by an actin- and myosin-dependent mechanism. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1847–1857. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00587-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schock F, Perrimon N. Molecular mechanisms of epithelial morphogenesis. Ann Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2002;18:463–493. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.18.022602.131838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troll JV, Adin DM, Wier AM, Paquette N, Silverman N, Goldman WE, FJ, et al. Peptidoglycan induces loss of a nuclear peptidoglycan recognition protein during host tissue development in a beneficial animal-bacterial symbiosis. Cell Microbiol. 2009;11:1114–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01315.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JR. ‘Putting the squeeze’ on the tight junction: understanding cytoskeletal regulation. Sem Cell Dev Biol. 2000;11:301–308. doi: 10.1006/scdb.2000.0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JE, Pettersen S, Stuestol JF, Wang YY, Foster SJ, Thiemermann C, et al. Peptidoglycan of S. aureus causes increased levels of matrix metalloproteinases in the rat. Shock. 2004;22:376–379. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000140299.48063.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe K. Collagenolytic proteases from bacteria. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004;63:520–526. doi: 10.1007/s00253-003-1442-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werb Z, Chin JR. Extracellular matrix remodeling during morphogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;857:110–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker JR, Granum PE. An absolute method for protein determination based on difference in absorbance at 235 and 280 nm. Anal Biochem. 1980;109:156–159. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler G, Paynter K, Fisher D. Matrix metalloproteinase-like activity from hemocytes of the easter oysterCrassostrea virginica. Comp Biochem Physiol B. 2002;131:361–370. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(01)00518-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]