Abstract

Genetic memory enables the recording of information in the DNA of living cells. Memory can record a transient environmental signal or cell state that is then recalled at a later time. Permanent memory is implemented using irreversible recombinases that invert the orientation of a unit of DNA, corresponding to the [0,1] state of a bit. To expand the memory capacity, we have applied bioinformatics to identify 34 phage integrases (and their cognate attB and attP recognition sites), from which we build 11 memory switches that are perfectly orthogonal to each other and the FimE and HbiF bacterial invertases. Using these switches, a memory array is constructed in Escherichia coli that can record 1.375 bytes of information. It is demonstrated that the recombinases can be layered and used to permanently record the transient state of a transcriptional logic gate.

Keywords: Synthetic biology, systems biology, biotechnology, genetic circuit, part mining

INTRODUCTION

Cells can remember events using a variety of biochemical mechanisms embedded in their regulatory networks1. For engineering applications, synthetic memory enables a signal to be recorded and accessed at a later time. In a bioreactor, it can convert transient conditions (e.g., inducer, growth phase, glucose concentration) into the permanent induction of metabolic pathways2, 3. During development, memory forms the basis of differentiation and this can be harnessed to divide complex tasks amongst individuals in a population (R. Egbert, L. Brettner, D. Zong and E. Klavins, University of Washington, unpublished). Memory can also be used to record transient signals that are difficult to record in situ4, 5; for example, stimuli experienced by bacteria in the gut microbiome6, 7. Larger memory capacities enable more information to be stored, which can be used to build circuits that require storage-and-retrieval and to program differentiation into a large number of cell states.

Several approaches have been taken to build synthetic memory. Genetic switches incorporating feedback loops can exhibit multi-stability and memory is implemented via the transition between stable steady-states8–11. The most common implementation is as a toggle switch, where repressors inhibit each other’s expression and a memory state corresponds with the dominance of one repressor9, 12. The feedback loop that maintains the memory state requires the continuous use of energy and materials for transcription and translation, analogous to volatile memory in electronic circuits.

A second approach is based on the use of recombinases that bind to two recognition sites and invert the intervening DNA. The states corresponding to the two orientations are non-volatile and will be maintained even after cell death. A bidirectional recombinase, such as Cre or Flp, catalyzes the orientation changes in both directions, which complicates their use for memory as their continued expression results in a distribution of states. Irreversible recombinases, such as FimE, only flip the DNA in one direction and thus implement permanent memory13. A memory circuit that can both be set and reset has been built using an integrase to flip in one direction and then the same integrase co-expressed with an excisionase to flip in the reverse direction14.

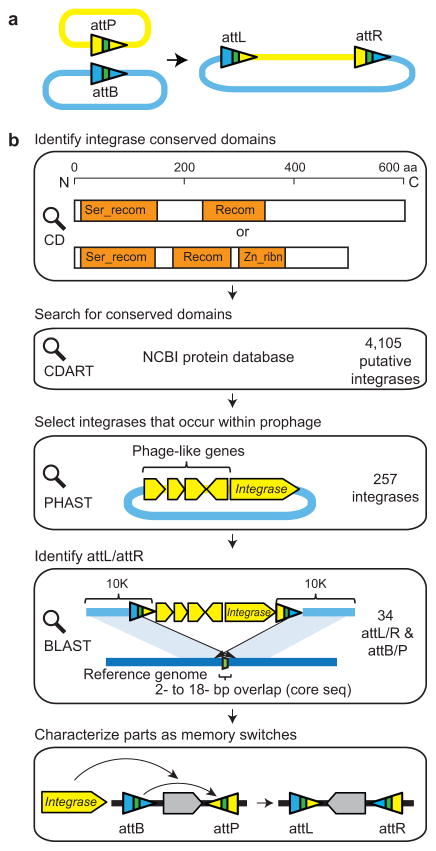

To date, the largest in vivo storage capacity has been 2 bits in Escherichia coli encoded by a pair of recombinases15, 16. The capacity has been limited by the need for the regulatory proteins underlying the memory switches to not interfere with each other. For example, a toggle switch requires two repressors and using N toggle switches in one cell would require 2N orthogonal repressors17. Recombinases are orthogonal if they do not bind to each other’s recognition sites. To this end, we have expanded the storage capacity of a recombinase-based memory array by mining orthogonal recombinases from prophage genomes. Our focus is on irreversible large serine type phage (LSTP) integrases, which are involved in mediating phage integration and excision into the bacterial genome between their cognate recognition sites, attB (bacterium) and attP (phage) (Fig. 1a)18. By placing these sites in the opposite orientation, LSTP integrases cleave, rotate and rejoin the DNA to invert the region between sites. A novel bioinformatics approach is applied to discover 34 putative integrases and their attB/P sites from prophage genomes. This set of new recombinases is used to build a memory array that is able to record 211 = 2048 combinations of states (1.375 bytes of information).

Figure 1. Discovery of phage recombinases and their recognition sites.(a).

LSTP integrases catalyze insertion of phage genome (yellow) into the bacterial genome (blue) between attB and attP sites, which form hybrid attL and attR sites (triangles). The colors illustrate the sequence changes that occur during strand exchange with the core sequence shown in green. (b)Each step is shown from integrase discovery to the construction of a memory switch. See text for details. The domain structure (orange) is shown for phiC31 (top) and BxB1 (bottom). Blue lines indicate the bacterial genomic DNA and yellow regions correspond to prophage. The strategy for identifying recognition sites for prophage that occur within genes differs slightly and is provided in Supplementary Figure 1. (c) The phylogenetic tree is shown for the complete set of 34 integrases. The Genbank ID of the integrases and the attB/P sequences are provided in Supplementary Table 1. The < symbols mark those integrases used to build memory switches.

RESULTS

Identification of LSTP integrases and att sites

The construction of a memory switch based on an integrase requires both its gene and the cognate attB/P recognition sites. This poses two challenges. First, identifying integrases is difficult because they are closely related to other classes of DNA modifying enzymes (e.g., transposases)19, 20. Second, the attB and attP sites are difficult to find because they are small and lack an obvious sequence signature19.

Since the discovery phage phiC31 integrase, only a few of LSTP integrases and their cognate attB/P sites have been identified18. To mine LSTP integrases from the genome database, we identified a set of conserved domains using Conserved Domain Search (CD search)21 and focused the search on these regions (Fig. 1b). The integrase from phiC31 contains two conserved domains: a “Ser_recombinase” domain (137 amino acids)19, 22,23 and a “Recombinase” domain (100aa)23. The integrase from phage Bxb1 contains an additional “Recombinase_Zinc_beta_ribbon” domain (57aa)23. These three domains are present in different combinations in other known phage integrases20. We used the Conserved Domain Architecture Retrieval Tool (CDART) to search the NCBI protein database to identify proteins containing at least the first two domains. This search yielded 4105 candidate LSTP integrases.

Building memory switches requires the identification of the attB /Precognition sites for each integrase. These sites were located using a strategy based on genome comparison. When a lytic phage integrates into a bacterial genome, the integrase recognizes attB and attP and within these sites the DNA is cleaved and strand exchange is catalyzed (Fig. 1a)18. Post-integration, the recombination forms new attL and attR sequences, which flank the prophage within the bacterial genome. The attB/P/L/R sites all share a common 2–18 bp “core” sequence. The first step to reconstructing these sequences was to retrieve the location of the 4105 LSTP integrases within all sequenced genomes in NCBI database. These genomes were then scanned using the PH Age Search Tool (PHAST), which detects clusters of phage-like proteins and provides approximate locations of prophage regions24. This yielded 257 integrase genes located within prophage regions.

Genome comparisons were used to determine the precise prophage boundaries. The region of the bacterial genome containing the prophage and 10kb of up and downstream sequence was compared using BLAST against homologous genome sequences from the same genus (Fig. 1b). Positive hits were signified by a 2–18 bp overlap identified in the alignment of the 10kb flanking sequences between the genome containing the prophage and the reference genome (Fig. 1b). The minimal att site length is 40–50 bp to ensure efficient recombination20. Therefore, we defined attL and attR as being a 59–66bp region surrounding the core sequence at the prophage boundaries. From this, the attB and attP sites were reconstructed by exchanging the half-sites of attL and attR based on their relationship shown in Figure 1A. A similar approach was taken when the prophage occurs within a gene encoding a conserved protein (Supplementary Note1 and Supplementary Fig.1). Using this strategy, we identified a library of 34 novel LSTP integrases and their attB/P sites, including 3 that were gleaned from the literature (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Table 1)25, 26. Most of these integrases share less than 65% amino acid identity (except Int7 and 22, Int8 and 21) and all have distinct attB and/or attP sites, making them unlikely to cross-react with each other.

Characterization of memory switches

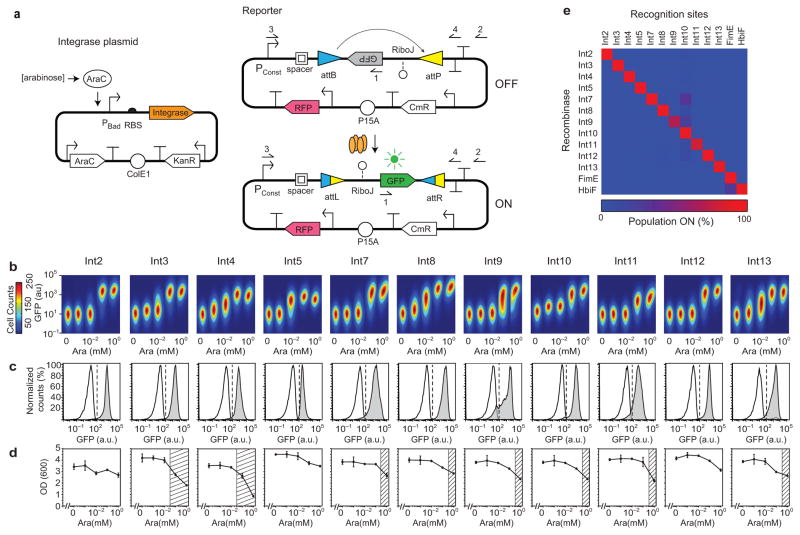

A subset of 13 integrases was selected to share a maximum of 60% amino acid sequence identity (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Table 1). Their corresponding genes were codon-optimized for expression in E.coli and built using DNA synthesis. A two-plasmid system was constructed in order to test their function and rapidly screen for orthogonality (Fig. 2A). The first plasmid contains the integrase gene under the control of the arabinose-inducible promoter, PBad. A second reporter plasmid contains the attB and attP sites flanking a green fluorescent protein reporter gene (gfp). A strong constitutive promoter (BBa_J23119) is placed upstream of the attB site, which transcribes in the opposite orientation as gfp. After the integrase is expressed, the orientation of gfp is inverted and it is transcribed. After inversion, the recombined attB and attP sites result in the formation of attL and attR. The attL site is located on the 5’-UTR and could impact gfp expression. To insulate against this effect, we included a spacer and the ribozyme RiboJ27, 28.

Figure 2. Memory switch characterization.(a).

The two-plasmid system is shown for assaying integrases and their recognition sites. The constitutive promoter (BBa_J23119) that controls GFP expression after DNA inversion is Pconst. Red fluorescent protein (RFP) is expressed from a constitutive promoter (BBa_J23101) in order to aid the gating of cells. The primer1, 2, 3 and 4 locations are used to assay the inversion event by PCR and sequencing. (b) An orthogonality matrix for the recombinases and their recognition sites is shown. The “Population ON” is the percent of cells above a GFP threshold of 102 au. The data represent the average of three independent replicates performed on different days (averages and standard deviations are provided in Supplementary Table 5). (c) The induction of each functional memory switch is shown. Five levels of arabinose induction are shown (left to right): 0, 10−3, 0.01, 0.1, and 1 mM. The heat map has the cell count, the height and width of the cell populations are the fluorescence from the green and red channels, respectively. The range of red fluorescence in each plot is 102.5–104.5 au on a log axis. The figure represents three experiments performed in different days. (d) Cytometry distributions of GFP fluorescence is shown before (white) and after (grey) arabinose. The dashed lines show the threshold at which cells are considered to be in the ON state (102 for all switches). Averages and error bars of three experiments performed in different days are shown in Supplemental Figure 3. (e)PCR bands amplified from cell cultures before (–) and after (+) arabinose induction using the primer 1 and 2 shown in part a. The expected band size is 0.8 kb. (f) The fraction of cells that are ON is shown versus time. Cells are induced at t = 0. (g) The impact on cell growth (OD 600nm) is shown as a function of arabinose concentration, corresponding to part b. The region where the growth rate is reduced by >25% is shown as a hashed region, chosen to be consistent with prior work34. The average and standard deviation is shown for three independent experiments.

The integrase and reporter plasmids were co-transformed into E. coli DH10b and tested for function. The expression of the integrase was varied by screening 16-32 ribosome binding sites predicted by the RBS Calculator to widely span expression levels29, 30. RBSs were selected that achieved the maximum GFP expression while minimizing leakage in the uninduced state (Supplementary Note 3 and Table 2). Remarkably, 11 of the 13 integrases were found to functional as confirmed by fluorescence, PCR and sequencing (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 3 and 4). For Int13, the attP site exhibited weak promoter activity, which was corrected by swapping its position with the attB site (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Note 2). We found only two integrases (1 and 6) non-functional and excluded them from further analysis.

Memory switches were constructed using the 11 functional recombinases (Fig.2a). The response function of each switch to increasing inducer concentration is shown in Figure 2c. The majority of the integrases are highly efficient at inverting their cognate attB/P sites, showing >90% of switching after 8 hours (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 3). There is negligible leakage for all of the switches at the uninduced state and no switching is observed by PCR (Fig. 2e). The quickest switching rate was exhibited by Int8, requiring <2 hours to fully turn on (Fig. 2f). Of the remainder, six required 2–4 hours and four turned on between 4–6 hours. These rates include the time required to activate the arabinose-inducible promoter, the expression of the integrase, the switching rate, and the expression of the GFP reporter to the steady-state level. The impact on growth was also measured (Fig. 2g) and the majority is non-toxic except at very high levels of expression.

Memory array composed of orthogonal switches

Amongst the 11 functional integrases, the attB/P sites share no nucleotide identity and even the size and sequence of the core differs considerably (Supplementary Table 3). In addition, orthogonality was tested for 2 bacterial invertases (FimE and HbiF) and their recognition sites31, 32. The recombinase and reporter plasmids were co-transformed into E. coli DH10b in all possible combinations. Each combination was assayed for activity, which is reported in terms of the % of the population that is expressing GFP (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 4 and Table 5) and the change in fluorescence that is observed (Supplementary Fig. 4, Fig. 5, and Table 6). There is no detectible crosstalk between the integrases and non-target recognition sites, except a low level of crosstalk between the Int10 recognition sites and the Int7,8 or 11 integrases. These data reveal that the 13 recombinases are highly orthogonal to one another.

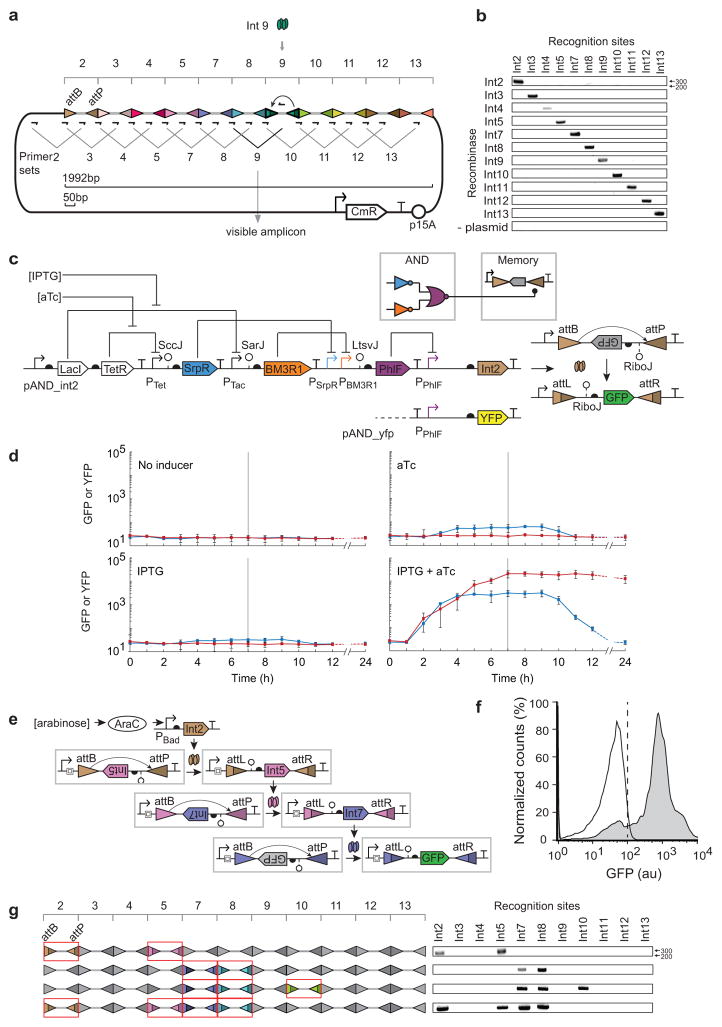

The orthogonality of the memory switches allows them to be used simultaneously to record different events. An array was constructed by concatenating the attB/P sites of the 11 phage integrases to form a linear 2kb piece of DNA (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Table 7). Random spacers (50 bp) with 50% GC content are included between the att sites (Supplementary Table 8). Unique primers were designed based on the locations of the attB/P sites to detect all possible 11 switching events (Supplementary Table 9). The final designed array is encoded in 2kb of DNA and can record 11 bits (1.375 bytes) of information. It can be used to distinguish 211 = 2048 possible combinations of events. The final array design was constructed using DNA synthesis.

Figure 3. Incorporation of recombinases into larger genetic circuits. (a).

The memory array was designed as a linear concatenation of recognition sites for each integrase. A different 50bp spacer (grey thick line) was placed between each pair of recognition sites. Primer pairs were designed where one occurs at the interface between recognition sites and the second is within the spacer. Only when a spacer is inverted does the associated primer occur in the correct orientation to be amplified by PCR (~300bp). Int9 is shown as an example. (b) A DNA gel (1% agarose) is shown where the each primer set is used to determine which inversion event occurred. The “plasmid” control refers to a strain that contains only the memory array plasmid, but no integrase plasmid. (c) The memory array recording multiple bits of information is shown. Multiple integrase genes (Int2/5, Int7/8, Int7/8/10 or Int2/5/7/8) were organized in an operon controlled by an arabinose inducible promoter. The memory array after inversion is shown on the left. Only the attB/P sites that are switched are colored (same as part a) and indicated by the formation of attL/R. The DNA bands amplified using 11 primer sets described in Figure 3a are shown on the right. (d)The wiring diagram (colored by repressor) and genetic system for the AND gate connected to a memory switch is shown. The AND gate is also connected to an yfp gene to be used as a control. (e) Each panel shows a different combination of inducer. Blue lines show the fluorescence when the PPhlF promoter is fused directly to yfp and the red lines show when it induces Int2. Inducers were added at t = 0 hours and removed at t = 6 hours (horizontal line). The last time point was taken at 24 hours; the dashed lines are an extrapolation to that point accounting for dilution due to cell division. The error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent experiments performed on different days. (f) The 3-layer cascade of phage integrases is shown. Each integrase changes the orientation of the same constitutive promoter (BBa_J23101) and the same spacer and RiboJ insulator is used to insulate the integrases at each stage. (g) The cytometry distributions are shown for the cascade in the absence (white) and presence (grey) of inducer. The vertical dashed line demarcates the threshold used to determine whether cells are on or off. The figure represents three experiments performed in different days.

The memory array plasmid (Fig. 3a) and each integrase plasmid (Fig.2a) were co-transformed in to DH10b. All the 11 strains containing the memory array plasmid and one of the integrase plasmids were induced with 2 mM arabinose for 4 hours. DNA inversion was assayed using the 11 pairs of primers designed for each recognition site. Amplification only occurs for the primer sets corresponding to the cognate pairs of integrase and attB/P sites (Fig. 3b). In the absence of inducer there is negligible background switching occurred (Supplementary Fig. 6). It is noteworthy that we only built one memory array for this work (none of an intermediate size) and all of the att sites were functional without additional tuning or debugging15.

1 bit memory array recording the output of a logic gate

The memory array is useful to permanently record whether a combination of environmental or cellular signals was encountered at the same time33. Transcriptional logic gates could perform signal integration, the output of which is recorded as memory that could be retrieved at a later stage of the computation. Logic operations based solely on recombinases are irreversible (once observed, an input signal can never be forgotten) and are thus unable to resolve the order or co-occurrence of input signals.

An example of combining digital logic with 1 bit memory is shown in Figure 3d. A transcriptional AND circuit is constructed by layering NOR and NOT gates. There are two inducible systems (LacI and TetR) that serve as surrogates for environmental signals. Their corresponding PTac and PTet promoters are the two input promoters to the circuit. The AND function is composed of two NOT gates and a NOR gate using the SrpR, BM3R1, and PhlF repressors, respectively34. Each repressor contains a variant of the RiboJ insulator (SccJ, SarJ, and LtsvJ) to reduce the effect of genetic context that arises from different promoter inputs28. The output promoter of the AND circuit (PPhlF) is connected to the Int2 integrase, which then interacts with the array to permanently record whether both input signals (aTc and IPTG) were observed at the same time.

The dynamics of the AND gate in the presence of different combinations of inputs is shown in Figure 3e and Supplementary Figure 7. The activation of the output promoter (PPhlF) without memory was measured separately (blue lines). The circuit turns on only in the presence of both inducers [1,1] and after 7 hours it reaches 60-fold induction. At this time point, the cells are diluted into media lacking inducer that returns the inputs to the [0,0] state. This reversal takes ~2 hours to begin, because the induced repressors must be diluted over time via cell division. The circuit returns to the off state with a timescale limited by degradation and dilution and by 24 hours the circuit has completely reverted. When the output of the AND gate is connected to the memory array, the circuit still relaxes to the off state (PPhlF), but the transient on state is recorded permanently (red line). There is a ~1 hour delay in triggering the memory switch and once the inversion occurs it produces stable expression for >24 hours. The switch also functions as a filter, where [aTc] alone causes a small increase in the output and this leakiness does not cross the threshold required for the memory switch. Also, the strong constitutive promoter in the switch functions to amplify the output of the circuit by increasing the dynamic range to over 1000-fold.

Circuits composed of multiple recombinases

Circuits were constructed to demonstrate that multiple orthogonal recombinases can be used in a single cell without interference over long time. Three of the new integrases (Int2, 5 and 7) were arranged to form a cascade (Fig. 3f). When cells are induced with arabinose for 12 hours, almost the entire population (92%) progresses to the final layer of the cascade (Fig. 3g). A shorter two-integrase cascade based on Int5 and 7 was constructed and 89% of the cells are induced after 8 hours (Supplementary Fig. 8). The average fluorescence of the induced population remains similar for the 2- and 3-integrase cascades (611±43 versus 908±10 au). This is expected because the same constitutive promoter is dictating the expression level at each layer. This is in contrast to transcription factor based cascades, where the signal properties change at each layers due to ultra sensitivity35, mismatches in the transfer function34, and the response properties of the final output promoter36, 37. Operons containing 2, 3 or 4 integrase genes (Int2/5, Int7/8, Int7/8/10 and Int2/5/7/8) were constructed to record 2, 3 or 4 bits information in the memory array (Fig. 3c and Supplemental Fig. 12). The integrases were induced with 2mM arabinose and DNA inversion was assayed with 11 pairs of primers as described in Figure 3a. Amplification was only detected for the primer sets of the corresponding integrases. This demonstrates the memory array is able to write multiple bits of information according to the expression of specific integrases. Note that using multiple integrases is not constrained by growth defect (Supplementary Fig. 9 and Note 4).

DISCUSSION

This work expands the programmable memory capacity in a living cell to beyond a byte of information. This allows engineering bacteria to permanently record multiple environmental and cellular stimuli that can be recalled at a later stage of the computation or interrogating the exposure of the bacteria to particular conditions. The design of the memory array is simple and robust, only requiring the stringing together of recognition sites into a linear DNA sequence. The combination of the recognition sites to build the array was easy and worked in the first attempt. The state of these memory devices can be read through reporter genes or nucleic acid-based assays even if the chassis organism is dead, which is beneficial for real-world applications. A memory array can be connected to an environmental sensor to elucidate how bacteria respond to difficult-to-assay environments, such as niches within the human body or within biofilms and microbial communities38.

The recombinases demonstrate exquisite orthogonality, with essentially no measureable crosstalk with off-target recognition sites. This differs from other DNA-binding proteins, where small operators and sequence degeneracy leads to crosstalk and thus many variants have to be screened to obtain a small orthogonal set34, 39, 40. All 11 integrases that were functional were also highly orthogonal and none had to be eliminated due to crosstalk. This allowed the recognition sites for all functional integrases to be used together to build an 11-bit array. This approach can be scaled to higher capacities as there are >4000 integrases in the sequence databases and our bioinformatics approach yielded 34 predicted att sites that are diverse and likely to be orthogonal. Increased memory capacity enables new classes of computing that can be performed in cells. Memory allows intermediate calculations to be stored so that the same computing units can be used repetitively, rather than having specialized computing-memory circuits. Almost all modern computers incorporate architectures analogous to Figure 3D, in which combinatorial logic circuits store the output of their computations in memory, which can then be accessed by later computing steps. This feature enables the creation of complex sequential logic systems and state machines.

Online Methods

Strains and media

E.coli DH10b (F–mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) ⌽80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 recA1 endA1 araD139 Δ(araleu) 7697 galU galK rpsL nupG λ–)41 was used for genetic manipulation and characterization. Note that E. coli DH10b has the fimE/fimB and fim structural genes deleted41. Cells were grown in LB miller broth (Difco, 90003-350) for functional assays and SOB (Teknova, S0210) (2% Bacto-tryptone, 0.5% Bacto yeast extract, 10 mMNaCl, 2.5 mMKCl) for cloning. Chloramphenicol (Alfa Aesar, AAB20841-14) (34 μg/ml), kanamycin (GoldBio, K-120-10) (50 μg/ml) or spectinomycin sulfate (50 μg/mL) (MP Biomedicals LLC, 158993) were supplemented where appropriate. Arabinose (Sigma Aldrich, MO, A3256), IPTG (Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside) (GoldBio, I2481C25) or anhydrotetracycline (aTc) (Sigma Aldrich, 37919) was used as inducers. For arabinose induction system 0.5% (w/v) glucose was used to reduce the leakiness of the uninduced state. Three fluorescence proteins GFPmut342, mRFP143 and YFP42 were used as reporters in this study.

Bioinformatics for integrase discovery

To identity more LSTP integrases from the protein database, the conserved domains of several known LSTP integrases were analyzed using ‘Conserved Domains’ search tool21(http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi) with default parameters (E-value<0.01). The integrase from phage phiC31 contains two conserved domains: a “Ser_recombinase” domain (137 aa)19, 22, 23 which is the catalytic domain and a “Recombinase” domain (100 aa)23 which is usually found in association with the “Ser_recombinase” domain. The integrase from phage Bxb1 contains an additional “Zn_ribbon_recom” domain (57 aa)23 which is a zinc ribbon domain likely to be involved in DNA binding. The NCBI protein database was searched for proteins that contain 2 or 3 of the identified domains using CDART with default parameters (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/lexington/lexington.cgi).

For each LSTP integrase candidate, the genome was retreated and scanned using PHAST24 (http://phast.wishartlab.com/) with default parameters to detect clusters of phage-like genesadjacent to the interested integrases genes. Integrases genes that are known or located in plasmids and phages were manually removed from the list. All the databases were updated until Oct. 22, 2012. To identify the attL and attR sites (prophage boundary), we searched the prophage genome together with 10kb up- and downstream sequences against all the homologous genomes belonging to the same genus using Megablast provided by NCBI (default parameters). The BLAST results were manually scanned for patterns described in Figure 1C and Supplemental Figure S1. Finally a library of 34 integrases and their cognate attL/R and attB/P sites were identified. The phylogenetic analysis of the 34 integrase protein sequences was performed using Clustal Omega (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/) (default parameters). The tree view was constructed using the ‘letsmakeatree’ function in Matlab (the MathWorks Inc.).

Codon optimization and DNA synthesis

The recombinase library was codon optimized by GeneArt (Regensburg, Germany) for E. coli K12 MG1655, synthesized, and assembled into the parent vectors using the one-step isothermal DNA assembly method44. The memory array was designed by concatenating the attB and attP sites of integrases 2,3,4,5,7,8,9,10 and 11 in numerical order. Between each attB/P site pair, a random 50bp spacer was inserted. The spacer was designedto have a GC content of 50% using the Sequence Manipulation Suite45. The 1992 bp design was synthesized by GeneArt and then assembled into the parent plasmid by golden gate method (Fig. 3b)46.

Flow cytometry analysis

Fluorescence was measured using an LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) or MACSQuant VYB (MiltenyiBiotec) with a 488nm laser for GFP and YFP measurement. For each sample at least 104 events were recorded using a flow rate of 0.5 μL/s. FlowJo v10 (TreeStar Inc.)was used to analyze the data. All events were gated by forward scatter, side scatter. RFP fluorescence (102 105au) was also used for gating cells containing the reporter plasmids. Events corresponding to negative GFP fluorescence were excluded. The background fluorescence of E. coli DH10b cells without plasmids was subtracted prior to calculating the fold change.

Characterization of memory switches

E. coliDH10b cells containing only the reporter plasmid were made chemically competent using Z-competent reagents (Zymo Research, T3001) and transformed with plasmids containing different integrases. The transformants were selected on LB agar (1%) supplemented with kanamycin, chloramphenicol and 0.5% glucose. Three colonies were picked for biological replication. The overnight cultures were prepared in LB supplemented with kanamycin, chloramphenicol in the presence of 0.5% glucose. For functional assays all cultures were grown at 37°C in V-bottom 96-well plates (Nunc, 249952) covered with air permeable membranes AeraSeal (E&K scientific) in an ELMI Digital Thermos Microplates shaker (1000 rpm) (Elmi Ltd). The transformation method and culture condition was used for Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure 3–5.

For Figure 2b–g, the transformants with the cognate pair of integrase-reporter plasmids were used to test the function of each integrase. The overnight cultures were washed twice with LB and diluted 200:1 in 200 μl LB containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin and 34 μg/ml chloramphenicol in the presence of various inducers. For Figure 2c, cells were induced with 0 (with 0.5% glucose, control), 0.001, 0.01, 0.1 or 1 mM arabinose for 8 hours. For Figure 2d and e, the cells were induced with 0 (with 0.5% glucose) or 1 mM arabinose for 8 hours. For Figure 2d, 25 μl of cultures were heated at 95oC for 10 min and 2μl of supernatants were used for PCR analysis. For Figure 2f the cells were induced with 1 mM arabinose for 15 hours. For flow cytometer analysis, a 2–20 μl aliquot of each culture was added to 198 μl PBS containing 2mg/ml kanamycin and stored at 4°C for 16 hours.

For Figure 2g, cells were induced with 0 (with 0.5% glucose), 0.001, 0.01, 0.1 or 1mM arabinose for 8 hours. 150 μl of cultures were transferred into a flat bottom 96-well plate (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark, 165305) to measure OD (600nm) using a Synergy H1 Hybrid Microplate Reader (BioTek, VM).

For Figure 2b and Supplementary Figure 5, cells containing all combinations of integrase plasmids and reporter plasmids were induced with 0mM (with 0.5% glucose) or 1mM arabinose for 6 hours and 2 μl of cultures were prepared as in Fig. 2 and used for flow cytometer analysis.

For Supplementary Figure9, overnight cultures were adjusted to the same OD and diluted 1:200 into LB (Kan, Cm) medium containing various concentrations of arabinose (0.5% glucose was supplement at 0mM ara) in 96-well plates sealed with Breath-easy sealing membrane (Sigma Aldrich) for 12 hours at 37 °C. A Synergy H1 Hybrid Microplate Reader (Biotek) was used for cultivation and OD measurement.

PCR and sequencing verification of DNA inversion

A set of primers was designed to confirm the DNA inversion catalyzed by the novel integrases by PCR analysis. Primer 1 (caataccttttaactcgattctattaacaag) was located in the middle of the gfp coding sequence and primer 2 (cagtgccaacatagtaagccagtat) was located downstream of the DNA inversion region (Fig. 2a). A PCR product was only generated when the cognate integrase was induced and DNA fragment between attB and attP was flipped. The PCR products were also sequenced using primer 1 to confirm that they contained the attR or attL sequences, as predicted. Primer 3 (ttgacagctagctcagtcctaggtataatgc) and primer 4 (ggggtttttttttgggtatgggccctag) (Fig. 2a) were also used to verify the OFF state by PCR and sequencing. The sequences of OFF state are the same as designed and an example of Int2 reporter (from the Pconst. to attB) is listed in Supplementary Table 4.

To analyze the memory array, E. coli DH10b cells were made chemically competent and co-transformed the memory device plasmid and each of the functional controller plasmids. Colonies were picked into LB + 0.4% glucose and grown overnight. Then, 10 μL of each culture was then added to 100 μL LB supplemented with 0.4% glucose (uninduced) or 100 μL LB supplemented with 2mM arabinose (induced). After 4 hours, 2 μL of each culture was added to a 25 μL GoTaq PCR mix (Promega) for each pair of analytical primers. All PCR reactions were run at 72°C for 25 cycles before electrophoresis in a 1% agarose gel. Inversion was indicated by the presence of a ~300bp band. Each of the induced cultures where flipping was observed was further confirmed by MiniPrep (Qiagen) and sequencing. Moreover, the sequence of memory array of pCis_7+10+8 and pCis_2+7+8+5 after induction were confirmed by sequencing the plasmids using primers JFR57 (cattttagcttccttagctcctg), CM209 (cattagaggtcgtatcctatcgcgataattcc) and CM213 (gcatgaggctgcctgagatcctcta). The sequence of memory array after induction of pCis_2+7+8+5 is shown in Supplementary Table 7.

Recording of the digital AND circuit

E. coli DH10b were co-transformed so that they contained either (a) pAND-yfp_ctr and pSpec, or (b) pAND_Int and pAND_reporter (Supplementary Fig. 10). The cultures were grown overnight in LB media with 50 μg/ml kanamycin and 50 μg/ml spectinomycin at 37°C and 1000 rpm using 2 ml 96 deep-well plates (USA Scientific, 1896-2000) in a Multitron Pro shaker-incubator (In Vitro Technologies). After overnight growth, cells were diluted 1:500 into 500 μL of LB with antibiotic in a new 96 deep-well plate and grown for 3 hours in the shaker-incubator. Next, a 10 μl aliquot of culture was suspended in 190 μl PBS with 2 mg/ml kanamycin and stored for cytometry analysis (time point at 0 hours). The remaining culture was divided into four 300 μl cultures by diluting cells 1:3 into media with antibiotic. Each of the four cultures contained a different combination of inducers. A timepoint was taken every hour for 7 hours by storing 10 μL of cells into PBS with kanamycin. During this time course, every hour, the cultures were diluted 1:3 into fresh LB with corresponding inducers and antibiotics. After the 7 hour time point, the cultures were spun down at 4000 rcf and resuspended in LB media without inducers; this wash step was repeated a second time. Time points continued to be taken every hour for 5 more hours by storing 10 μL of cells in PBS with kanamycin, and then diluting cultures 1:3 into fresh LB with antibiotics and without inducers. Subsequently, the cells were grown overnight for 12 more hours without dilution. Finally, 1 μL of cells was stored in 199 μl PBS with 2 mg/ml kanamycin for flow cytometry analysis.

Analysis of integrase cascades

E. coli DH10b cells were transformed with either a) pInt5 and pCasc_5+7_gfp or b) pCas_2+5 and pCas_5+7_gfp (Supplementary Fig. 11). Three colonies were picked for biological replication. The overnight cultures were prepared in LB supplemented with 50 μg/ml kanamycin, 34 μg/mlchloramphenicol. The overnight cultures were diluted 1:200 into 200μl LB media supplemented with kanamycin and chloramphenicol and induced with 0mM arabinose or with 1mM arabinose. The cells were grown aerobically at 37°C, 1000 rpm for 12 hours in V-bottom 96-well plates (Nunc, 249952) covered with air permeable membranes AeraSeal (E&K scientific) in an ELMI Digital Thermos Microplates shaker (Elmi Ltd). For FACS analysis 2 μl of each culture was added to 198 μl PBS (stored at 4°C) containing 2mg/ml kanamycin for flow cytometer analysis and RFP fluorescence was used to assist gating cells.

Characterization of the memory array controlled by multiple integrases

Different combinations of integrase genes were cloned in a polycistron under the control of the PBad promoter, leaving the original RBS listed in Supplementary Table 2 intact. Plasmids containing these combinations were transfomed into cells containing an array of 11 integrase sites (Fig. 3a) and cultured onto LB agar plates containing kanamycin and chloramphenicol and supplemented with 0.5% glucose. Next day, single colonies were inoculated into 500 μL LB with kanamycin and chloramphenicol plus 0.5% glucose and grown overnight. These overnight cultures were then diluted 1:20 into 5mL of fresh LB containing kanamycin and chloramphenicol and either supplemented with 0.5% glucose (uninduced conditions) or 1 mM arabinose (induced conditions). Cells containing a 2-integrase plasmid (pCis_2+5 or pCis_7+8) were grown under these conditions for 4h; cells with a 3-integrase plasmid (pCis_7+10+8) were grown in the same conditions overnight; and cells containing the 4-integrase plasmid (pCis_2+7+8+5) were grown overnight under induced/uninduced conditions and next day diluted 1:20 into fresh LB plus antibiotics to be subjected to a second cycle of induction. For all integrase combinations, 4 μL of the final culture were used in a PCR reaction to query the state of their cognate site plus all the other integrase sites using primers listed in Supplementary Table 9. The plasmid maps are shown in Supplementary Figure 12. The plasmids used in this study are available upon request at Addgene (http://www.addgene.org/browse/pi/626/articles/).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

C.A.V., T.L, and L.Y. are supported by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA CLIO N66001-12-C-4016). C.A.V. and A.A.K.N are supported by the Defense Advanced Research Project Agency (DARPA CLIO N66001-12-C-4018). C.A.V., M.L., A.A.K.N. and J.F. are supported by the Office of Naval Research (ONR) Multidisciplinary University Research Initiative (MURI grant N00014-13-1-0074; Boston University MURI award 4500000552). C.A.V. is also supported by US National Institutes of Health (GM095765), the US National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS grant P50 GMO98792) and US National Science Foundation (NSF) Synthetic Biology Engineering Research Center (SynBERC EEC0540879) A.A.K.N receives Government Support FA9550-11-C-0028 and is awarded by the Department of Defense, Air Force Office of Scientific Research, National Defense Science and Engineering Graduate (NDSEG) Fellowship, 32 CFR 168a.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.A.V. and L.Y. conceived of the study and designed the experiments. L.Y., A.A.K.N., C.J.M. and J.F.R. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. C.A.V., L.Y., A.A.K.N. and C.J.M. wrote the manuscript. C.A.V., T.K.L. and M.T.L. managed the project.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Burrill DR, Silver PA. Making cellular memories. Cell. 2010;140:13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamanishi M, Matsuyama T. A modified Cre-lox genetic switch to dynamically control metabolic flow in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. ACS Synth Biol. 2012;1:172–180. doi: 10.1021/sb200017p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ham TS, Lee SK, Keasling JD, Arkin AP. A tightly regulated inducible expression system utilizing the fim inversion recombination switch. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2006;94:1–4. doi: 10.1002/bit.20916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kawashima T, et al. Functional labeling of neurons and their projections using the synthetic activity-dependent promoter E-SARE. Nat Methods. 2013;10:889–895. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zariwala HA, et al. A Cre-dependent GCaMP3 reporter mouse for neuronal imaging in vivo. J Neurosci. 2012;32:3131–3141. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4469-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kotula JW, et al. Programmable bacteria detect and record an environmental signal in the mammalian gut. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:4838–4843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321321111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Archer EJ, Robinson AB, Suel GM. Engineered E. coli that detect and respond to gut inflammation through nitric oxide sensing. ACS Synth Biol. 2012;1:451–457. doi: 10.1021/sb3000595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ingolia NT, Murray AW. Positive-feedback loops as a flexible biological module. Curr Biol. 2007;17:668–677. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gardner TS, Cantor CR, Collins JJ. Construction of a genetic toggle switch in Escherichia coli. Nature. 2000;403:339–342. doi: 10.1038/35002131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ajo-Franklin CM, et al. Rational design of memory in eukaryotic cells. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2271–2276. doi: 10.1101/gad.1586107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burrill DR, Inniss MC, Boyle PM, Silver PA. Synthetic memory circuits for tracking human cell fate. Genes Dev. 2012;26:1486–1497. doi: 10.1101/gad.189035.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greber D, El-Baba MD, Fussenegger M. Intronically encoded siRNAs improve dynamic range of mammalian gene regulation systems and toggle switch. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:e101. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moon TS, et al. Construction of a genetic multiplexer to toggle between chemosensory pathways in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 2011;406:215–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonnet J, Subsoontorn P, Endy D. Rewritable digital data storage in live cells via engineered control of recombination directionality. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:8884–8889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202344109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonnet J, Yin P, Ortiz ME, Subsoontorn P, Endy D. Amplifying genetic logic gates. Science. 2013;340:599–603. doi: 10.1126/science.1232758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedland AE, et al. Synthetic gene networks that count. Science. 2009;324:1199–1202. doi: 10.1126/science.1172005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nielsen AA, Segall-Shapiro TH, Voigt CA. Advances in genetic circuit design: novel biochemistries, deep part mining, and precision gene expression. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2013;17:878–892. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown WR, Lee NC, Xu Z, Smith MC. Serine recombinases as tools for genome engineering. Methods. 2011;53:372–379. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith MC, Thorpe HM. Diversity in the serine recombinases. Mol Microbiol. 2002;44:299–307. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith MC, Brown WR, McEwan AR, Rowley PA. Site-specific recombination by phiC31 integrase and other large serine recombinases. Biochem Soc Trans. 2010;38:388–394. doi: 10.1042/BST0380388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marchler-Bauer A, Bryant SH. CD-Search: protein domain annotations on the fly. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W327–331. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li W, et al. Structure of a synaptic gamma delta resolvase tetramer covalently linked to two cleaved DNAs. Science. 2005;309:1210–1215. doi: 10.1126/science.1112064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rutherford K, Yuan P, Perry K, Sharp R, Van Duyne GD. Attachment site recognition and regulation of directionality by the serine integrases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:8341–8356. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou Y, Liang Y, Lynch KH, Dennis JJ, Wishart DS. PHAST: a fast phage search tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W347–352. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Canchaya C, et al. Genome analysis of an inducible prophage and prophage remnants integrated in the Streptococcus pyogenes strain SF370. Virology. 2002;302:245–258. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brenciani A, et al. Phim46.1, the main Streptococcus pyogenes element carrying mef(A) and tet(O) genes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:221–229. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00499-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deuschle U, Kammerer W, Gentz R, Bujard H. Promoters of Escherichia coli: a hierarchy of in vivo strength indicates alternate structures. EMBO J. 1986;5:2987–2994. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04596.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lou C, Stanton B, Chen YJ, Munsky B, Voigt CA. Ribozyme-based insulator parts buffer synthetic circuits from genetic context. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:1137–1142. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salis HM, Mirsky EA, Voigt CA. Automated design of synthetic ribosome binding sites to control protein expression. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:946–950. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farasat I, et al. Efficient search, mapping, and optimization of multi-protein genetic systems in diverse bacteria. Mol Syst Biol. 2014;10:731. doi: 10.15252/msb.20134955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klemm P. Two regulatory fim genes, fimB and fimE, control the phase variation of type 1 fimbriae in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 1986;5:1389–1393. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04372.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xie Y, Yao Y, Kolisnychenko V, Teng CH, Kim KS. HbiF regulates type 1 fimbriation independently of FimB and FimE. Infect Immun. 2006;74:4039–4047. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02058-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clarke EJ, Voigt CA. Characterization of combinatorial patterns generated by multiple two-component sensors in E. coli that respond to many stimuli. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2011;108:666–675. doi: 10.1002/bit.22966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stanton BC, et al. Genomic mining of prokaryotic repressors for orthogonal logic gates. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:99–105. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hooshangi S, Thiberge S, Weiss R. Ultrasensitivity and noise propagation in a synthetic transcriptional cascade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:3581–3586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408507102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moon TS, Lou C, Tamsir A, Stanton BC, Voigt CA. Genetic programs constructed from layered logic gates in single cells. Nature. 2012;491:249–253. doi: 10.1038/nature11516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tamsir A, Tabor JJ, Voigt CA. Robust multicellular computing using genetically encoded NOR gates and chemical 'wires'. Nature. 2011;469:212–215. doi: 10.1038/nature09565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Costello EK, Stagaman K, Dethlefsen L, Bohannan BJ, Relman DA. The application of ecological theory toward an understanding of the human microbiome. Science. 2012;336:1255–1262. doi: 10.1126/science.1224203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rhodius VA, et al. Design of orthogonal genetic switches based on a crosstalk map of sigmas, anti-sigmas, and promoters. Mol Syst Biol. 2013;9:702. doi: 10.1038/msb.2013.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khalil AS, et al. A synthetic biology framework for programming eukaryotic transcription functions. Cell. 2012;150:647–658. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Durfee T, et al. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli DH10B: insights into the biology of a laboratory workhorse. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:2597–2606. doi: 10.1128/JB.01695-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cormack BP, Valdivia RH, Falkow S. FACS-optimized mutants of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) Gene. 1996;173:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00685-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Campbell RE, et al. A monomeric red fluorescent protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:7877–7882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082243699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gibson DG, et al. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat Methods. 2009;6:343–345. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stothard P. The sequence manipulation suite: JavaScript programs for analyzing and formatting protein and DNA sequences. Biotechniques. 2000;28:1102–1104. doi: 10.2144/00286ir01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Engler C, Gruetzner R, Kandzia R, Marillonnet S. Golden gate shuffling: a one-pot DNA shuffling method based on type IIs restriction enzymes. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5553. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.