Abstract

Objectives

Approximately 32.7% of people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) in the U.S. are now over the age of 50. Women comprise a significant percentage of the U.S. HIV epidemic and the percentage of women diagnosed with HIV continues to grow; however, little is known about women’s experiences living and coping with HIV over time. The goal of this study was to explore experiences of U.S. women over 50 living with HIV to better understand how they make sense of their diagnosis and cope with their illness over time, and during the aging process.

Method

Nineteen women (mean age = 56.79, SD=4.63) referred from Boston-area organizations and hospitals completed one-time, in-depth individual interviews. 47% of participants identified as Black/African American, and 37% as White. Average time since diagnosis was 16.32 years (SD=5.70). Inclusion criteria included: female sex; aged 50 or older; HIV diagnosis; and English speaking. Transcribed interviews were analyzed using a grounded theory approach and NVivo 9 software.

Results

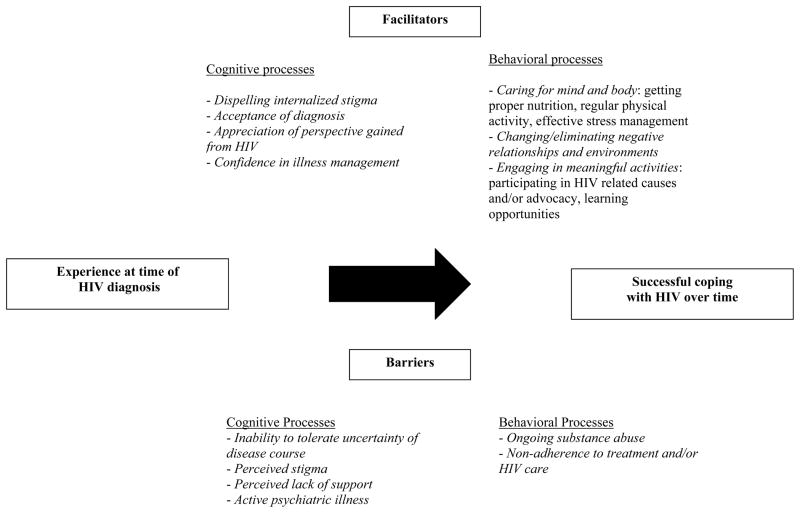

Findings are described across the following themes: 1) experiences at diagnosis, 2) uncertainty of disease course, 3) acceptance, 4) living “well” with HIV. Participants appeared to be well-adjusted to their HIV diagnosis and described a progression to acceptance and survivorship; they identified strategies to “live well” in the context of HIV. For some, health-related uncertainty about the future remained. These findings were organized into a model of coping with HIV.

Conclusions

Themes and issues identified by this study may help guide interventions across the lifespan for women with HIV.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, women, aging, adjustment, coping

It is estimated that 10,257 women were diagnosed with HIV in the United States in 2011 (CDC, 2013). Although advances in HIV treatment over the past two decades have vastly improved health outcomes and increased life expectancy for people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA; Rodger et al., 2013; Walensky et al., 2006), HIV remains a serious illness and infected individuals face a number of challenges, such as stigma and mental heath comorbidities (Bhatia, Hartman, Kallen, Graham, & Giordano, 2011; Pence, 2009; Tucker, Burnam, Sherbourne, Kung, & Gifford, 2003). Literature examining the short-term consequences of an HIV diagnosis has generally focused on men who have sex with men (MSM), and, while this literature has increased in recent years, reports on the experience of living with HIV over time among any subpopulation of individuals living with HIV are sparse. As the percentage of women diagnosed with and living with HIV continues to grow, this subpopulation will demand greater attention.

In many settings, PLWHA can expect to live close to a normal lifespan with ongoing medical care (Rodger et al., 2013; van Sighem, Gras, Reiss, Brinkman, & de Wolf, 2010; Walensky et al., 2006). As of 2009, approximately 32.7% of PLWHA in the U.S. were over the age of 50 and many of these individuals are among the first people in the U.S. to live with HIV over long periods of time (CDC, 2012). There is strong evidence that PLWHA are at psychological risk as they adjust to a new HIV diagnosis (Bhatia et al., 2011; Ciesla & Roberts, 2001; Cooperman & Simoni, 2005) and some studies have documented high rates of depressive symptoms among older PLWHA (Grov et al., 2010; Heckman et al., 2002). However, few studies have examined the progression of HIV-related adjustment and coping over time from the perspective of long-term survivors, particularly women.

Understanding how older women living with HIV make sense of their diagnosis and manage their illness over time may help inform the care of both newly diagnosed women and women living with HIV as they age. The following study used qualitative research methods to explore and understand how HIV-positive women over 50 experience living with HIV; the goal of this study was not to compare and contrast living with HIV over time with other chronic illnesses, but rather to provide a first hand account of older women’s experiences with HIV as older adults, and specifically, how this experience has evolved over time. Themes related to perceptions of living and coping with HIV over time emerged from a series of in-depth qualitative interviews, which were used in the analyses.

Methods

Participants

We purposively sampled older women living with HIV (homogeneous sampling) to participate in semi-structured qualitative interviews. The inclusion criteria were: (1) female sex; (2) aged 50 or older; (3) diagnosis of HIV/AIDS; and (4) English speaking. The only exclusion criterion was being unable or unwilling to provide informed consent. The primary means of recruitment was the use of flyers posted in Boston-area community HIV/AIDS organizations and referrals of eligible women by healthcare providers in the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Infectious Disease Clinic. Participants were also recruited from the screening efforts of a concurrent randomized controlled trial conducted at MGH that tested cognitive-behavioral therapy for adherence to HIV medications and depression in HIV care settings. Women who were screened for the randomized controlled trial and who appeared to meet criteria for the current study were provided with information and invited to participate. IRB approval from MGH/Partners HealthCare was obtained. Interviews were conducted between June 2009 and February 2010.

Measures

A semi-structured interview guide, developed using guidelines articulated by Huberman and Miles (2002), was used to collect qualitative data. The questions were designed to capture women’s experiences with HIV as they age and were developed through input from experts experienced in providing medical and psychiatric care to HIV-positive populations. The interview guide was piloted with the first four participants to assess its clarity and content, and revised to include questions on novel topics that emerged from the pilot interviews. Interviews began with a free-list activity whereby participants were asked to list the challenges faced by women over the age of 50 living with HIV. This was followed by questions exploring the issues raised by the interviewee during the free-list activity as well as the following topic areas, which were selected after a review of the literature to identify areas important to those living with HIV, older women, or both: (1) mental health concerns/cognitive functioning, (2) sexual functioning, (3) menopause, (4) quality of life, (5) social support, and (6) management of multiple health conditions/adherence to care. Sample questions and probes are provided in Table 1. Questions were open-ended in order to minimize the risk of biasing participants’ responses and to allow for novel themes to emerge. Participants were paid $25 for their time participating in the single 1–1.5 hour interview; a single interview was utilized in order to minimize participant burden. Interviews were administered by the first author, and were conducted until saturation occurred. While we surveyed participants on multiple areas, data presented here are related to the themes that emerged related to participants’ experiences living with HIV over time.

Table 1.

Sample study content areas and sample questions/probes

| Content area | Sample Questions and Probes |

|---|---|

| Opening questions/orientation to interview |

|

| Free-list exercise |

|

| Management of health |

|

| Emotional health |

|

| Social support |

|

| Sexual functioning |

|

Analyses

The qualitative interviews were audio-taped and transcribed. Using a grounded theory approach, content analyses were conducted using NVivo 9 software (2010) to uncover themes related to HIV and aging (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). This entailed an iterative multi-step process performed by the authors using the techniques described by Miles and Huberman (1984). We first identified major themes. Coding was then performed to structure data into categories and to create groups. Themes were then reexamined, and major and minor themes within each content area were identified; messages were extracted and highlighted. To ensure reliability, two coders analyzed the data independently. To check for validity, at each phase of the analyses the authors discussed their findings to assure that the interpretation of data was not being influenced by preconceived theories. Additionally, results from each phase of analyses were compared and discrepancies were discussed between the coders until a resolution was reached. An audit trail of coding templates and discussions about the data and computerized coding was kept. We referred to this audit trail to resolve discrepancies, and compared computerized coding to raw data. We cross-compared data for differences in experiences by race (White or Caucasian, Black or African American, and “other”) and education (high school GED or less and some college/college degrees/graduate degree) since those areas represented the greatest heterogeneity, and did not discern any thematic differences.

Results

Sociodemographic data on the 19 participants are presented in Table 2. Data from the 19 qualitative interviews were distilled into three major themes that emerged as influencing how women think about living with HIV and cope with the disease over time.

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics of Sample

| Variable | Participant Sample (N=19)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Age | ||

| M = 56.79 | - | - |

| SD = 4.63 | - | - |

| Race/Ethnicity* | ||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 2 | 10.5 |

| Asian | 1 | 5.3 |

| Black or African American | 9 | 47.4 |

| White or Caucasian | 7 | 36.8 |

| Latina | 1 | 5.3 |

| Education | ||

| Less than High School degree | 5 | 26.4 |

| High School graduate/GED | 5 | 26.3 |

| College/Graduate School Partial/Degree | 9 | 47.4 |

| Employment | ||

| Part-time | 6 | 31.6 |

| Disabled/Retired | 13 | 68.4 |

| Income | ||

| Under 15,000 | 14 | 73.7 |

| Relationship status | ||

| Single | 6 | 31.6 |

| Married/Partnered | 3 | 15.8 |

| Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 10 | 52.6 |

| Years since diagnosis | ||

| M = 16.32 | ||

| SD = 5.70 | ||

| HIV risk factors* | ||

| Sex with men only | 18 | 97.7 |

| IV drug use | 11 | 57.9 |

| Blood transfusion | 2 | 10.5 |

| Current antiretroviral treatment | 14 | 87.5 |

Categories not mutually exclusive

Experiences at diagnosis

Participants described an evolution of beliefs related to what it means to live with HIV over time, specifically, a transition from fear and disbelief at the time of diagnosis to gradual acceptance. The prognosis for participants at the time of diagnosis was often grim. Participants felt they were given a “death sentence” and were fearful that they were going to die very quickly as a result of HIV. One 55 year old, black participant who had been diagnosed with HIV for 13 years noted, “You fear so many things and then you get HIV and it’s in the category of the worst possible thing. And then, I didn’t die, you know? It made me want to live… it brought out a real fighting spirit.”

Uncertainty of disease course

While most women felt better adjusted to living with HIV over time, some uncertainty remained, and in this sample of older women, intensified with age. Specifically, women described a sense of “waiting for the other shoe to drop” whereby they might run out of treatment options, their bodies might “give out,” and a general sense of uncertainty about their health status. For example, a 64 year old, black participant who had been diagnosed for 14 years noted the following when asked about the stressors associated with the intersection of age and HIV, “The waiting and the anticipation of when it’s going to break out… when it will become a not just a symptom, but an active disease. And knowing with age that the body is not capable of fighting back like it used to when it was 30 or 40.” Another 57 year old, white participant who was diagnosed 20 years prior remarked, “I think that it just makes it a little bit harder. The natural aging process, and then you have that [HIV] on top of it. The longer I live, the more problems can develop. It takes a lot of work to maintain it [health].” The fear of running out of treatment options was also noted. One 54 year old, black participant described herself as a “dead woman walking,” while another 62 year old, black participant said, “It just never leaves you, you know. You know there are treatments, but there is no cure.”

Process of acceptance over time

With time, women described a transition to a sense of acceptance of their diagnosis. Acceptance encompassed a positive change in the perception about what it means to live with HIV (which was based on experience over time) and a sense of appreciation of life and the perspective gained as a result of their diagnosis. For example, a 63 year old, black participant diagnosed 12 years ago noted, “It becomes less catastrophic. Still devastating, and I still wish it wasn’t me, but it is, so I’ve got to move on.” For some participants, HIV is not perceived as badly as some other illnesses, as evidenced by the following quote, provided by a 52 year old, white participant diagnosed ten years prior:

“I would rather be HIV-positive than have cancer or diabetes. Because as long as I stay clean and sober, live my life to the best of my ability, take my medications and do all the things my doctor tells me to do, I’m going to live a long and fulfilled life.”

The same participant later noted:

“I don’t want it, but I have it, and what am I going to do? Live my life miserable because I’m HIV positive, and die a very lonely, hateful human being because I have the virus? No. I’m going to live life to the fullest and do the best that I can.”

Another 52 year old, white participant noted the following when describing the process of acceptance, which for her meant overcoming negative stigma and perceptions of “people with HIV”: “It’s actually part of who I am… and it doesn’t make you a bad person or a dirty person because you have the virus.”

In addition, some participants described a sense of gratefulness and an appreciation for life that they were able to achieve, a perspective that perhaps they wouldn’t have had if not for their diagnosis, as illustrated by the following quote, provided by a 56 year old Asian American participant who had been living with HIV for 24 years, “Each year that the anniversary of the date comes up, I celebrate. I celebrate it because I am blessed to be on this earth living. Twenty-four years to be living with HIV is a long time, so I don’t feel sorry for myself. I celebrate my life.” At diagnosis, many women did not believe that they would live to age, and reflected that they may view the aging process and death differently than women without HIV. For example, one black, 62 year old participant who was diagnosed in the late 80s remarked, “I don’t really worry about the aging thing because I know that I could have been gone. I could have been dead, you know?” This sentiment was echoed later by the same participant, who said, “It’s just good to be getting older. You know, if I didn’t have the disease, I’d probably say, ‘This sucks!’, but being that I do have the disease… you know?” Another black participant who was 54 years old and had been diagnosed 13 years ago made the following remark when describing thoughts about growing older with HIV, “To me, well, there’s a fear, but there is also a silver lining that I’m finding difficult to describe.”

Strategies for living successfully with HIV over time

Over time, participants learned how to effectively cope with HIV. Three subthemes related to living successfully with HIV over time emerged, including 1) caring for mind and body, 2) changing or eliminating negative relationships or environments, 3) engaging in meaningful activities. With respect to managing health, participants had a keen understanding of the connection between body and mind, as evidenced by the following quote by a 55 year old, mixed race participant, “I keep my life as stress free as I can. I think with or without HIV, stress is a killer.” Another 57 year old, white participant stated, “My goal in life is to be as comfortable as I can be, physically and mentally. Because that’s what makes a healthy, happy person.” Managing stress, depression, and anxiety was considered a key strategy to promote wellness, and participants utilized a variety of tools with which to accomplish this. Participants discussed the importance of utilizing supports, such as therapy, support groups and family members in order to optimize their emotional well-being.

Participants who seemed to be coping well with the illness described a growing intolerance of “toxic” factors in their lives that came with age, such as substance abuse and unhealthy relationships with others. For example, one participant, a 56 year old Asian American who was able to stop using substances noted:

“When I got to 50 and had a drug problem still, at 50 years old, I was disgusted with myself. And that’s when I decided enough is enough. When I hit 50 years it was like a slap in the head. My life went by and I don’t even remember anything of it. So I made many attempts to get clean, and I finally got clean.”

Another 52 year old, white participant described her understanding of why she used substances for so long:

“You know, if you keep your mind on positive things, then you’ll think positive things. If you keep your mind on negative things, like ‘I’m going to die’, you know in six months I’m going to shoot heroin again. I want to live my life to the fullest until the day I die, whether it’s six months from now or 30 years from now. I don’t ever want to stick another needle in my arm again.”

The importance of giving up “toxic” relationships is illustrated by the following quote from a 57 year old, white participant, “I think with age what I found out… I don’t have any toxic relationships right now. Some people are high maintenance and you just don’t miss having them in your life.” Another 54 year old, American Indian participant reflected, “My tolerance level is very low. Any kind of chaos. I used to be attracted to that life, but not anymore. Age definitely plays a factor”.

Participants also talked about how to “live” with HIV. Part of learning to live in the context of a chronic, but still life threatening, disease involved using their diagnosis as a catalyst for change and making a contribution to the next generation. Many participants talked about how they were able to interpret their diagnosis as an opportunity to do something different with their lives. Participants discussed their realization that they could learn and do new things, despite HIV, as evidenced by the following quote, provided with a 60 year old, black participant who was diagnosed in 1998, “I didn’t know I could do all that. It’s amazing. The disease is not really a conquering disease. You may have it and it can work your nerves if you let it, but you can do a lot of things.” Another 62 year old, black participant, also diagnosed in the late 80s, said the following, “I thought I was only going to live for a few months. It’s been a great challenge because I’ve gotten some good things out of it… like, learning so much. Everyday is a challenge because I am learning different things.”

Contributing to HIV prevention and awareness emerged as an important means by which to cope with HIV. Participants discussed the importance of protecting young and older women from HIV, educating the public about the face of HIV, and advancing the health agenda of women who are aging with HIV. One 62 year old, black participant noted, “Going to different colleges to speak – that really helps me a lot, and makes me feel like somebody. Because somebody’s listening, and I have impacted somebody’s life.” Other participants talked about educating their granddaughters and friends about HIV prevention. Another 62 year old, black participant talked about her role in an HIV support group, “There are a lot of women in their 30s, and I have a little bit more knowledge. And they can see, ok, you can live. So I think it’s important for me to be involved in a support group.” Similarly, another 54 year old, American Indian participant talked about her experiences helping newly diagnosed individuals, “I’m grateful it’s been 24 years. I like helping other people, especially newly diagnosed people. I’m participating in training around peer navigating to help people that have had the same struggles.”

Discussion

The current study explored women’s experiences living and coping with HIV as older adults, with a focus on adjustment and coping over time. In general, this sample of women over 50 living with HIV appeared to be well-adjusted with respect to their HIV diagnosis. With age came knowledge and understanding of what it means to live with HIV and how to “live well” and cope effectively in the face of an HIV diagnosis. Women described a clear progression of feelings such as shame and disbelief at the time of diagnosis, to acceptance and survivorship at present. Despite this shift, for some women, health-related uncertainty about the future remained and was intensified by age.

Participants often initially assumed that life was over at diagnosis, but the experience of growing older with HIV caused women to reexamine those beliefs. This often spurred a desire to begin “living” again. In order to live well and cope with the demands of HIV, women made their health a priority and sought ways to maximize well-being. This encompassed taking care of both body and mind by seeking emotional support from friends, family, and therapy, and making efforts to exercise and eat well. Women emphasized the need to eliminate “toxic” forces in their lives, such as drug abuse and relationships with “toxic” people. Another aspect of living well with HIV involved making meaning of their diagnosis; this was often accomplished by acts of service to the HIV community. Some women began attending support groups to offer their support to those recently diagnosed with HIV. Others participated in research, or educated family and friends about HIV prevention. Despite these efforts, women recognized that they were aging, and some worried that they may run out of treatment options or that their aging bodies may just “give out” in response to the stress of managing HIV over time. These findings are consistent with recent studies that have examined aging among older PLWHA and highlight the importance of concepts such as resilience, optimism, and problem-focused coping to facilitate successful aging and better quality of life (Emlet et al., 2011; Moore et al., 2013; Slater et al., 2013).

Another recent study examining stress and social isolation among older PLWHA found that participants who were age 50 or older reported less perceived stress and social isolation when compared to participants 49 years or younger (Webel et al., 2014). These findings and those from the current study may be best understood from a framework of adult development, such as the model of strength and vulnerability integration (SAVI; Charles, 2010), which, in brief, posits that with age, individuals are better able to regulate their emotional experiences as a result of improvements in the use of “attentional strategies, appraisals, and behaviors”. Using perspective that comes from an understanding of “time lived and time left to live”, older adults are said to both minimize exposure to negative emotional stimuli and modulate their reactions to such stimuli when confronted by them. When these two conditions are possible, emotional well-being is preserved. However, when these conditions are not met, such as when avoidance is not possible, these age-related gains are reduced, and distress follows. The participants in this study south out experiences where stigma would be less likely (e.g., within the HIV community) and eliminated “toxic” people and circumstances in their lives. They also reflected and readjusted their expectations for themselves about what it meant to receive and HIV diagnosis (e.g., the evolution from feeling “dirty” to acceptance) and how to live their lives in a meaningful way (e.g., service to the community). Uncertainty about disease course is an area in which these strategies are less effective, and this remained a source of distress.

In general, most will adjust to an HIV diagnosis. However, the time of diagnosis can be a time of tremendous distress (Bhatia et al., 2011; Ciesla & Roberts, 2001; Cooperman & Simoni, 2005), and it is important to understand processes that support the transition from distress to healthy coping. Data from this study may provide suggestions as to how interventions can be developed to help women move from distress to healthy coping. These data were organized into a model demonstrating factors that facilitate or serve as barriers to transitioning to a healthy coping style that emerged from our data (see Figure 1). Barriers and facilitators are separated into cognitive and behavioral processes. With respect to facilitators of the transition, cognitive processes involving acceptance, appreciation, and reduced stigma appear important, while behaviorally, participants described the importance of caring for their bodies and minds and making a meaningful life. Cognitive processes that represented barriers included the difficulty accepting the uncertainty of the course of the disease and a perceived lack of support, while behaviorally, ongoing substance abuse and nonadherence to care served as barriers to successful living with HIV. These targets could be worked with within the context of a cognitive-behavioral intervention, which have been used with success in various populations of individuals living with or at risk for HIV (e.g., Malow et al., 2012; Safren, O’Cleirigh, Bullis, Otto, Stein, & Pollack, 2012; Trafton et al., 2012).

Figure 1.

Barriers and facilitators to successful coping with HIV over time

For some participants, meaning was achieved by participating in support groups and providing encouragement to newly diagnosed women. Peer-support interventions have been used with some success in PLWHA, including Fogarty et al. (2001), Simoni et al. (2009), and Safren et al. (2011). Key components of these successful peer interventions include one-on-one counseling with a trained peer familiar with group norms and tailoring of the interventions to include the most pertinent topics (such as substance use, condom use, disclosure, and HIV communication). A peer-support intervention whereby women who have lived with HIV over time serve as mentors to newly diagnosed women may both attenuate the negative impact of an HIV diagnosis and help older women with HIV “live well” with HIV. Assessing whether this type of support would be wanted among newly diagnosed women and whether women “veterans” of HIV would want to serve this role in a formal way requires study. However, these women are a wealth of valuable knowledge and may help newly diagnosed women start on the path to “living well” with HIV sooner. Peer support models also provide opportunities for building social relationships, the presence of which have been associated with lower levels of depressive symptoms among older PLWHA (Grov et al., 2010; Mavandadi et al., 2009; Schrimshaw & Siegel, 2003)

In addition, long-term survivors may benefit from additional support and knowledge about what to expect as they age further with HIV. As these women are among the first to traverse the path of living with this disease over time, the answers that they desire may still elude the healthcare community at this time. Additional study of this population in terms of disease progression, treatment options, how to effectively manage various age associated comorbidities, and the aging process is warranted in order for providers to best care for an aging HIV positive population, as well as those who continue to be diagnosed each year.

The current study has some limitations. The first is the small sample size and the recruitment strategies may preclude findings from being generalizable to all populations of older, HIV-positive women. Specifically, while the goal of qualitative research is not necessarily generalizability, we may have accessioned a population of women who were coping well with HIV. However, interviewing occurred until we reached thematic saturation. It is also difficult to ascertain from the data and the study design whether women’s adjustment was fueled by wisdom that may come with age, or direct experiences that came from living with HIV. As a qualitative study, findings may be interpreted as hypothesis-generating for future research, and need to be replicated using quantitative methodologies, particularly the proposed model. Quantitative assessment of specific coping strategies would also inform intervention development. Given that the sample consisted of women with minimal formal education and who were socioeconomically disadvantaged, it would be of particular value to understand specifically how they managed to overcome barriers to the implementation of coping strategies. Despite these limitations, these data provide valuable information about how women integrate HIV into their lives, how they may be helpful to women just starting a similar journey, and how as healthcare providers we can best care for this population.

In summary, while an HIV diagnosis may result in distress, it is likely that many women will adjust to their diagnosis over time, and do relatively well with respect to living with HIV. However, even the women in this sample who are reportedly coping well with HIV give us some insight into what might be targets of intervention for women in this age group who struggle with effective coping, such as those who struggle with uncertainly about the future of their health. It also tells us what we can do to facilitate wellbeing, namely, help women identify ways to care for their bodies and minds, (e.g., exercise and stress management programs that are available to all, regardless of socioeconomic status), foster supportive social networks, and find ways to facilitate positive engagement in the community. These women may have a great deal to teach not only the scientific community, but other women trying to navigate learning to live with HIV.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Psaros’ time was supported by the Harvard University Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH funded program (P30 AI060354) which is supported by the following NIH Co-Funding and Participating Institutes and Centers: NIAID, NCI, NICHD, NHLBI, NIDA, NIMH, NIA, NCCAM, FIC, and OAR, and K23 MH096651. Additional author time was supported by K01 AI062435 (Robbins), and K24 MH094214 (Safren).

Contributor Information

Christina Psaros, Email: cpsaros@partners.org.

Jennifer Barinas, Email: Jennifer.barinas@gmail.com.

Gregory K. Robbins, Email: grobbins@partners.org.

C. Andres Bedoya, Email: abedoya@partners.org.

Elyse R. Park, Email: epark@partners.org.

Steven A. Safren, Email: ssafren@partners.org.

References

- Azar MM, Springer SA, Meyer JP, Altice FL. A systematic review of the impact of alcohol use disorders on HIV treatment outcomes, adherence to antiretroviral therapy and health care utilization. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;112:178–193. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia R, Hartman C, Kallen MA, Graham J, Giordano TP. Persons newly diagnosed with HIV infection are at high risk for depression and poor linkage to care: Results from the Steps Study. AIDS and Behavior. 2011;15:1161–1170. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9778-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bing EG, Burnam MA, Longshore D, Fleishman JA, Sherbourne CD, London AS, Shapiro M. Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:721. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.8.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance report, 2010. 2012;22 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/surveillance/resources/reports/2010report/pdf/2010_HIV_Surveillance_Report_vol_22.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST. Strength and vulnerability integration: A model of emotional well-being across adulthood. Psychological Bulletin. 2010;136:1068–1091. doi: 10.1037/a0021232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among Women. Fact Sheet. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/gender/women/facts/index.html#ref3.

- Ciesla JA, Roberts JE. Meta-analysis of the relationship between HIV infection and risk for depressive disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:725–730. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.5.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooperman NA, Simoni JM. Suicidal ideation and attempted suicide among women living with HIV/AIDS. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;28:149–156. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-3664-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emlet CA, Tozay S, Raveis VH. “I’m not going to die from the AIDS”: resilience in aging with HIV disease. The Gerontologist. 2011;51:101–111. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogarty LA, Heilig CM, Armstrong K, Cabral R, Galavotti C, Gielen AC, Green BM. Long-term effectiveness of a peer-based intervention to promote condom and contraceptive use among HIV-positive and at-risk women. Public Health Reports. 2001;116:103. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.S1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garder EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, del Rio C, Burman W. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2011;52:793–800. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grov C, Golub SA, Parsons JT, Brennan M, Karpiak SE. Loneliness and HIV-related stigma explain depression among older HIV-positive adults. AIDS Care. 2010;22:630–639. doi: 10.1080/09540120903280901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman TG, Kochman A, Sikkema KJ. Depressive symptoms in older adults living with HIV disease: Application of the Chronic Illness Quality of Life Model. Journal of Mental Health and Aging. 2002;8:267–279. [Google Scholar]

- Huberman M, Miles MB, editors. The qualitative researcher’s companion: Classic and contemporary readings. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Israelski DM, Prentiss DE, Lubega S, Balmas G, Garcia P, Muhammad M, Koopman C. Psychiatric co-morbidity in vulnerable populations receiving primary care for HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 2007;19:220–225. doi: 10.1080/09540120600774230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly B, Raphael B, Judd F, Perdices M, Kernutt G, Burnett P, Burrows G. Posttraumatic stress disorder in response to HIV infection. General Hospital Psychiatry. 1998;20:345–352. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(98)00042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan AP, Sayles JN, Patel VA, Remien RH, Ortiz D, Szekeres G, Coates TJ. Stigma in the HIV/AIDS epidemic: a review of the literature and recommendations for the way forward. AIDS. 2008;22:S67. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000327438.13291.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malow RM, McMahon RC, Dévieux J, Rosenberg R, Frankel A, Bryant V, Miguez M. Cognitive behavioral HIV risk reduction in those receiving psychiatric treatment: A clinical trial. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16:1192–1202. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0104-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavandadi S, Zanjani F, Ten Have TR, Oslin DW. Psychological well-being among individuals aging with HIV: the value of social relationships. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2009;51:91–98. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318199069b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: A source book of new methods. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Moore RC, Moore DJ, Thompson WK, Vahia IV, Grant I, Jeste DV. A case-controlled study of successful aging in older HIV-infected adults. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2013;74:e417–423. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m08100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison MF, Petitto JM, Ten Have T, Gettes DR, Chiappini MS, Weber AL, Evans DL. Depressive and anxiety disorders in women with HIV infection. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:789–796. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software (Version 9) [computer software] Doncaster, Australia: QSR International Pty Ltd; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pence BW. The impact of mental health and traumatic life experiences on antiretroviral treatment outcomes for people living with HIV/AIDS. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2009;63:636–640. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pence BW, Miller WC, Whetten K, Eron JJ, Gaynes BN. Prevalence of DSM-IV-defined mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders in an HIV clinic in the Southeastern United States. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2006;42(3):298–306. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000219773.82055.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power R, Koopman C, Volk J, Israelski DM, Stone L, Chesney MA, Spiegel D. Social support, substance use, and denial in relationship to antiretroviral treatment adherence among HIV-infected persons. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2003;17:245–252. doi: 10.1089/108729103321655890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puskas CM, Forrest JI, Parashar S, Salters KA, Cescon AM, Kaida A, Hogg RS. Women and vulnerability to HAART non-adherence: a literature review of treatment adherence by gender from 2000 to 2011. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2011:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11904-011-0098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodger AJ, Lodwick R, Schecter M, Deeks S, Smin J, Gilson R, Paredes R, Bakowska E, Engsig FN, Phillips A. Mortality in well controlled HIV in the continuous antiretroviral therapy arms of the SMART and ESPRIT trials compared with the general population. AIDS. 2013;27:373–979. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835cae9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, O’Cleirigh C, Skeer MR, Driskell J, Goshe BM, Covahey C, Mayer KH. Demonstration and evaluation of a peer-delivered, individually-tailored, HIV prevention intervention for HIV-infected MSM in their primary care setting. AIDS and Behavior. 2011;15:949–958. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9807-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, O’Cleirigh C, Bullis JR, Otto MW, Stein MD, Pollack MH. Cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in HIV-infected injection drug users: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:404–415. doi: 10.1037/a0028208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayles JN, Ryan GW, Silver JS, Sarkisian CA, Cunningham WE. Experiences of social stigma and implications for healthcare among a diverse population of HIV positive adults. Journal of Urban Health. 2007;84:814–828. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9220-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrimshaw EW, Siegel K. Perceived barriers to social support from family and friends among older adults with HIV/AIDS. Journal of Health Psychology. 2003;8:738–752. doi: 10.1177/13591053030086007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni JM, Huh D, Frick PA, Pearson CR, Andrasik MP, Dunbar PJ, Hooton TM. Peer support and pager messaging to promote antiretroviral modifying therapy in Seattle: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2009;52:465–473. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e3181b9300c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater LZ, Moneyham L, Vance DE, Raper JL, Mugavero MJ, Childs G. Support, stigma, health, coping, and quality of life in older gay men with HIV. The Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care: JANAC. 2013;24:38–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss AC, Corbin JM. Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Trafton JA, Sorrell JT, Holodniy M, Pierson H, Link P, Combs A, Israelski D. Outcomes associated with a cognitive-behavioral chronic pain management program implemented in three public HIV primary care clinics. The Journal Of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2012;39:158–173. doi: 10.1007/s11414-011-9254-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, Burnam MA, Sherbourne CD, Kung FY, Gifford AL. Substance use and mental health correlates of nonadherence to antiretroviral medications in a sample of patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. The American Journal of Medicine. 2003;114:573–580. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00093-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Sighem A, Gras L, Reiss P, Brinkman K, de Wolf F. Life expectancy of recently diagnosed asymptomatic HIV-infected patients approaches that of uninfected individuals. AIDS. 2010;24:1527–1535. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833a3946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanable PA, Carey MP, Blair DC, Littlewood RA. Impact of HIV-related stigma on health behaviors and psychological adjustment among HIV-positive men and women. AIDS and Behavior. 2006;10:473–482. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9099-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walensy RP, Paltiel AD, Losina E, Mercincavage LM, Schackman BR, Sax PE, Weinstein MC, Freedberg KA. The survival benefits of AIDS treatment in the United States. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2006;194:11–19. doi: 10.1086/505147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webel AR, Longenecker CT, Gripshover B, Hanson JE, Schmotzer BJ, Salata RA. Age, stress, and isolation in older adults living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2014;26:523–531. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.845288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whetten K, Reif S, Whetten R, Murphy-McMillan LK. Trauma, mental health, distrust, and stigma among HIV-positive persons: implications for effective care. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2008;70:531–538. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31817749dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]