Abstract

Innovation is a form of purposeful discovery behavior that exploits the unexpected, utilizes imagination, and provides one avenue of new solutions to complex human health needs. It is through this lens that two examples are described in which innovative approaches have been used to dissect the complexities of stroke pathophysiology. The first example focuses on one of the most fundamental genetic factors relevant to the brain and ischemic injury: biological sex. Much might be gained by understanding the details of sex-specific pathobiology, if the field is to develop therapies that work well in patients of both sexes. The second example surrounds brain-spleen cell cycling after stroke which is fundamental to our evolving understanding that stroke is a systemic disease, rather than solely a lesion of the brain. While much work remains, it is now apparent that brain-spleen cell cycling is temporally specific, varies in intensity, and involves cell players that are of much wider lineages than originally believed. In the future, it is likely that innovation will need to turn to “big data”, particularly if our field is to tackle the daunting questions that most greatly matter to unraveling brain injury. The huge availability and growth rate of biomedical data, handled in a shared but coherent environment, offers an opportunity to further vitalize stroke research.

Keywords: cerebral ischemia, gender, immune system, innovation, sex, spleen, stroke, Willis

Looking at stroke research through the lens of Innovation

The Willis Lecture Award recognizes the contributions of Thomas Willis who is widely regarded as the father of modern neurology. This 17th century clinician scientist was arguably the first to correlate bedside observations of neurological disease with anatomical constructs of the brain and its circulation. What is most striking about his career is its natural seeking of innovative solutions and novel answers to poorly understood problems. It is Willis as an “innovator” that makes him so compelling a historical model for those who seek new discoveries about stroke today.

Innovation is typically defined as creativity with a purpose1. The word, innovation, crops up daily in our conversations now, an activity that seems almost self-evident in its desirability. But innovation is not necessarily a matter of technical capability. It is a purposeful discovery behavior that exploits the unexpected, utilizes imagination, and provides one avenue of new solutions to complex human health needs. It is through this lens that the 2014 Willis Lecture re-examined the impact of two stories of stroke research that unfolded through the combined efforts of investigators from many disciplines, frequently executed through collaborative team science. The first story surrounds one of the most fundamental genetic factors relevant to the brain and ischemic injury: biological sex. A number of recent reviews are available for deep dives into the data surrounding this topic 2-5. The second exemplar, of brain-spleen cell cycling, is fundamental to the concept that stroke is a systemic disease, rather than a lesion solely of the central nervous system (CNS).

Sex matters in cell death

Literature spanning decades has catalogued sex differences in brain structure, neurochemistry, and cerebral vasculature in animals. More recently post-mortem studies and neuroimaging using single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), positron emission tomography (PET), structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI and fMRI, respectively) have unlocked sex differences in humans. There are many similarities, but also important differences, between the brains of men and women in health and disease. Simple examples include the larger overall size brain in men than in women, and a higher percentage of gray matter in women and of white matter in men6. Global cerebral blood flow is higher in women than in men, at rest and during cognition7, and there are sex-specific regional flow differences. The brains of both sexes are neurochemically distinct in dopaminergic, serotonergic, and GABAergic neurotransmission7, and recent work is uncovering significant sex differences in cerebral gene expression and epigenetic regulation8. Most striking are the differences in the structural connectome of the brain between the sexes. For example, at the supratentorial level, males have greater within-hemispheric connectivity, as compared to greater between-hemispheric connectivity in women. In the cerebellum, the opposite is true9. The suggestion is that male brains are structured for greater connectivity between areas controlling perception and motor function, while female brains are better connected for communication9. These structural differences have clear implications for stroke survivors, both in terms of the functional deficits experienced and the potential for re-connecting damaged neural pathways.

It has been recognized for many years that stroke rates are higher in men vs. women globally 10, and that this sexually dimorphic epidemiology persists until ages well beyond the menopausal years11. In children, sex differences in stroke risk and pathobiology are evident even before puberty 12. While the importance and mechanisms of female gonadal steroids have been heavily studied in the injured brain, the aggregate data suggest that hormones do not fully account for male vs female cerebrovascular disease patterns. An alternative explanation is that chromosomal, genetic sex (XX vs XY based) acts on a molecular platform established early in development by sex steroids.

The jump from the known epidemiology to a new understanding began by simply asking if outcomes in experimental models of brain injury also reflected this sexual dimorphism and if so, how deeply did sex differences penetrate into mechanisms of cell death. Early data from standard focal and global cerebral ischemia models in animals suggested that favorable outcomes occurred more frequently in females than in males, even in the presence of co-morbidities, e.g. diabetes and hypertension 2,13,14. These data pointed the way toward the need to solve technical demands that would allow the use of sex-stratified, in vitro cell systems in stroke research. The new approach allowed the challenge of the long-held assumption that the mechanisms and outcomes of injury in culture are independent of the sex of the cells.

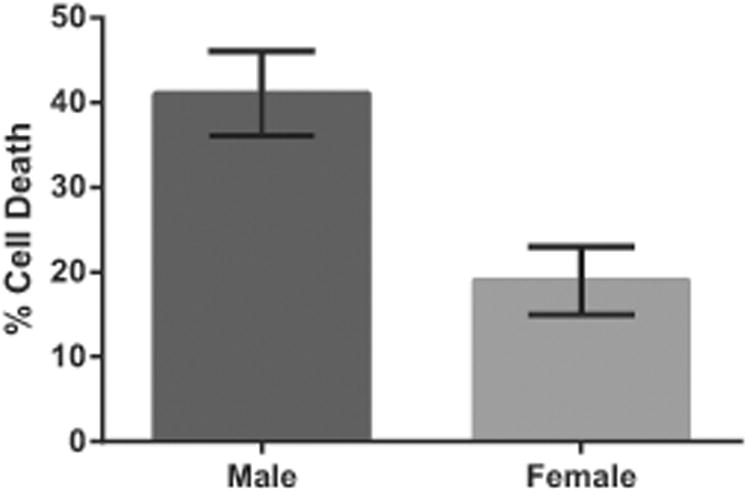

Consequently, studies carried out in primary cell cultures (i.e. cells obtained from sexed rodent embryos and grown in the absence of sex steroids in the culture media) were able to demonstrate and track the relative sensitivities of XX and XY cells to injury. Similarly, sex differences could be elucidated in experimental paradigms that use pharmacological probes to evaluate molecular signaling cell death pathways. The earliest example is from the study by Du et.al. with systematic observations that male and female neurons proceed to cell death via differing molecular pathways. 15 XY neurons are more susceptible to glutamate and peroxynitrite (ONOO−) induced injury, while XX neurons are more sensitive to staurosporine, triggering apoptosis. To simulate ischemic injury, we and others have exposed sex-stratified primary astrocytic or cerebral microvascular endothelial cell cultures to oxygen–glucose deprivation (OGD). In each case, XX cells tolerate OGD to a greater extent than do XY cells (Fig. 1) 16,17. In part, XX astrocytes enjoy relative protection due to their capacity to express high levels of P450 aromatase, allowing the local synthesis of anti-oxidant estradiol. Studies of various neuronal populations suggest that sex differences are more varied than in astrocytes, with reports of high XY sensitivity in hippocampal neurons18 but high XX sensitivity when neurons are selected from cerebellar granular layers 19. More structured tissue cultures, such as those arising from hippocampal slices, demonstrate high XY sensitivity to OGD relative to matched female slices20.

Fig. 1.

Data from primary astrocyte cultures: XX cells tolerate oxygen and glucose deprivation (OGD) with lower mortality than do XY cells. For details on technical methods, see reference 17.

Using sex-stratified animal and cell models, it became possible for the first time to understand how XX vs XY cells might rely on differing ischemic cell death molecular signaling or engage differing protective molecules in the face of injury. Such molecules include apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF), caspase 3, glutathione, both the neuronal and inducible isoforms of nitric oxide synthase, poly-ADP ribose polymerase (PARP), P450 aromatase, superoxide dismutase and others 2. Many sexually dimorphic molecules have been identified through the use of knockout mice as the practice of using all male animals has lessened, but much work remains. For example, only a few studies have used tissue and cell-specific knockouts to more carefully parse out sex differences. And few sex-specific mechanisms have evaluated for their hormone-dependent or independent properties. Given the high failure rate of experimental neuroprotective therapies to advance care for patients of either sex, capitalizing on the sex specificity of death mechanisms could be a valuable first step toward “personalized” therapeutic interventions.

Lastly, while the epidemiology of stroke incidence may be favorable to females vs. males until advanced age, outcomes from stroke in women are not favorable. Once stroke occurs, women can sustain severe damage with high short-term mortality relative to men, and experience considerable loss of quality of life21-23. So much might be gained by understanding the details of sex-specific pathobiology.

Brain-spleen cross-talk after stroke

A second story of research innovation centers on the under-estimated effect of dual super-system activation (the CNS and the immune system) and how this interaction complicates cerebral ischemia. Over the course of this work, we learned that stroke in humans and animals precipitates damage to immune organs and that spleen cells engage in crosstalk with the brain “lesion”. By way of context, it has been long recognized that acute stroke patients may survive initial brain events, only to experience delayed recovery, or even death, due to infectious complications. The potential for aberrant systemic immune function in such complications has been described clinically and experimentally (for reviews, 24-28). But the underlying immunology has been understudied, in part because the stroke field lacked neuroimmunologists at the experimental table. In this story, the jump from the known complications of stroke to a new understanding of process began through the questions of an immunology colleague about the state and function of the post-stroke spleen, thymus and lymph nodes in murine focal stroke models 29-40.

To answer these novel questions, we and others began to evaluate how focal cerebral ischemia altered the structure and function of lymphoid tissue outside of the brain. For the first time, spleens, thymi, and lymph nodes were examined alongside the brain in our standard mouse stroke models. We found that ischemic brain injury leads to biphasic consequences. First, there is a rapid splenic activation within 6 hours of the brain insult in which splenocytes produce massive internal levels of inflammatory chemokines and cytokines (e.g. TNF-α, IL-6, IL-2, MCP-1, and MIP-2), with similar changes occurring in lymph nodes and blood 29-30. Perhaps in response to sympathetic nervous system hyperstimulation, the activated spleen releases subsets of immune cells into the blood, e.g. T and B lymphocytes, macophages, and dendritic cells. Second, there is a delayed, but massive and progressive, splenic apoptosis in which the organ visibly shrivels in size, and its cells are selectively destroyed in their inflammatory mileau. By 96 hours after stroke, spleen cell numbers are drastically reduced relative to sham-treated mice or mice naïve to injury. These splenic changes do not appear to directly influence early infarct size in mice, but the animal's ability to respond to antigenic challenges is exhausted (a significant measure of immunosuppression). For example, T lymphocyte reponse to antigens ConA and anti-CD3mAB are all strongly decreased, likely due to reduced T cell numbers and the increased suppressive activity of T regulatory cells. Some part of these processes may also occur in patients. Pilot studies suggest that daily speen size changes after acute ischemic stroke, first a contraction then re-expansion, as measured by abdominal ultrasound. When individual patients were further analyzed, daily spleen volume changes were positively associated with clinical course41.

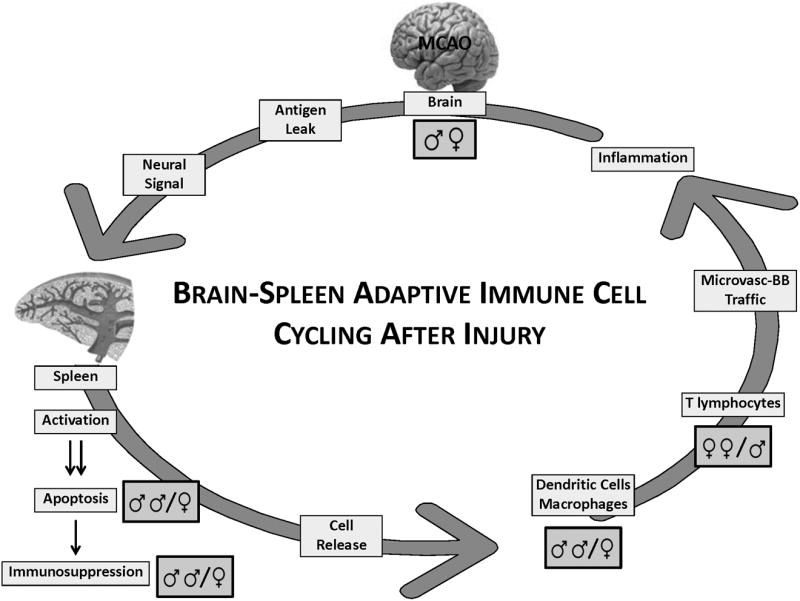

Subsequent studies deepened our understanding that cells of splenic origin enter the brain and amplify known local brain inflammatory processes arising from polymorphonuclear neutrophils and resident microglia. We coined this process as “brain-spleen cell cycling” after stroke (Fig.2). The evolving brain injury “signals” for the biphasic activation and atrophy of the spleen, followed by apoptosis and compromised immune function. Remaining intra-splenic cell subsets are released into the blood, followed by trafficking across a cerebral microvasculature replete with inflammatory display of adhesion molecules and chemokines. Interestingly, early studies now show that some of these processes are influenced by sex and sex steroids 33,35,39.

Fig 2.

Brain-spleen immune cell cycling after experimental stroke. The evolving brain injury "signals" through the central nervous system for activation and apoptosis of the spleen, with consequent loss of many splenic immunocytes, leading to systemic immunosuppression. Remaining intra-splenic cell subsets (e.g. macrophages, lymphocytes and dendritic cells) are released into the blood, followed by trafficking across a cerebral microvasculature replete with inflammatory display of adhesion molecules and chemokines. The result is enhanced cerebral inflammation and damage, thus re-invigorating the cycle. Several points in the cycle are hypothesized to be sex-dependent. For example, splenic consequences post-experimental stroke have been observed to be more robust in male vs. female mice. Further, inflammatory cell trafficking is not identical in the male vs female post-ischemic brain. For example, macrophage infiltration into brain is particularly robust in male mice. Whether this observation is best explained by the typically larger infarct in male vs. female brain after experimental ischemia (middle cerebral artery occlusion), or by specific mechanisms of cell trafficking is unclear at present.

A key assumption in the cycling hypothesis is that adaptive immune cells must be triggered through an encounter with brain–derived antigens, either in soluble form or as presented by macrophages or dendritic cells. Under ordinary circumstances, the CNS is generally “immune privileged” in that brain is isolated from the immune system by a functional blood brain barrier. Following injury, antigen presenting cells may leave the brain and be transported by the blood or cerebrospinal fluid to lymphoid tissue, including the cervical lymph nodes. A unique observation is that brain-derived material, e.g. myelin or subunits of the NMDA receptor, can be identified by immunoreactivity in the palatine tonsils and cervical lymph nodes of acute stroke patients 42. Leakage of brain auto-antigens such as myelin basic protein or myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) might produce important autoimmune responses. For example, using an adoptive transfer technique and MOG reactive cells 37, MOG-reactive splenocytes which secrete toxic Th1 cytokines (e.g. IFN-γ and TNF-α) were transferred into severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice. This maneuver resulted in increased infarct size, increased neurological deficits and a higher accumulation of immune cells in ischemic brain in the treated mice relative to control animals.

While much work remains, brain-spleen cell cycling may be temporally specific and varies in intensity, depending on the size of initial brain infarction. The cell players involved are of much wider lineages than originally believed, involving both innate and adaptive immune cell types, and may be controlled by different mechanisms. For example, a previously unknown role for B regulatory lymphocytes in experimental stroke is now widely recognized 36,38. B regulatory cells, acting through IL-10 dependent protective mechanisms, diminish stroke volume, improve neurological damage, and reduce infiltration of inflammatory leukocyte subsets such as Gr1+neutrophils, CD3+T lymphocytes, and CD11b+CD45high macrophages after focal cerebral ischemia.

Embracing the next innovation

Watchers of innovation, and those of us who hold large ambitions for the future of stroke research, will readily seek bold new approaches across basic, translational, clinical and population sciences. As shown by the two exemplatives offered here, innovation springs quickly when collaborators of very different disciplines learn to speak each other's language. Or when quixotic, “out-of-the box” questions can rise to the forefront of one's research. But in the future, innovation in stroke research will need to turn to “big data”, particularly if we are to tackle daunting questions that taunt us with difficult breakthroughs. The huge availability and growth rate of biomedical data, handled in a shared but coherent environment, offers an opportunity to further vitalize stroke research. Unlike the advances in cancer care and discovery, big data approaches are still rare in stroke studies at the bench or in the clinic. Envision the potential for innovation as we accumulate the stroke genome on a thumb drive, linked to clinical and epidemiological data, and coupled with post-stroke brain connectome imaging. Perhaps even Thomas Willis would be intrigued!

Acknowledgments

With gratitude to the many colleagues, fellows, students and trainees who have taught me so much, so far. The author thanks Ms. Mary Avila and Julie Palmateer for expert preparation of the figures in this manuscript. Supported by NIH grant NR03521.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

References

- 1.Ness RB. Innovation Generation. Oxford University Press; New York: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herson PS, Palmateer J, Hurn PD. Biological sex and mechanisms of ischemic brain injury. Transl Stroke Res. 2013;4:413–9. doi: 10.1007/s12975-012-0238-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gibson CL. Cerebral ischemic stroke: is gender important? J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:1355–61. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu F, McCollough LD. Interactions between age, sex and hormones in experimental ischemic stroke. Neurochem Int. 2012;61:1255–65. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haast RA, Gustafson DR, Kiliaan AJ. Sex differences in stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:2100–7. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cahill L. Why sex matters for neuroscience. Nature Reviews Neurosci. 2006;7:477–84. doi: 10.1038/nrn1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cosgrove KP, Mazure CM, Staley JK. Evolving knowledge of sex differences in brain structure, function and chemistry. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:847–855. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jazin E, Cahill L. Sex differences in molecular neuroscience: from fruit flies to humans. Nature Reviews Neurosci. 2010;11:9–17. doi: 10.1038/nrn2754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ingalhalikar M, Smith A, Parker D, Satterthwaite TD, Elliott MA, Ruparel K, et al. Sex differences in the structural connectome of the human brain. PNAS. 2014;111:823–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316909110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sudlow CL, Warlow CP. Comparable studies of the incidence of stroke and its pathological types: results from an international collaboration. Stroke. 1997;28:491–9. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.3.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sacco RL, Boden-Albala B, Gan R, Chen X, Kargman DE, Shea S, et al. Stroke incidence among white, black, and Hispanic residents of an urban community: the Northern Manhattan Stroke Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147:259–68. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fullerton HJ, Wu YW, Zhao S, Johnston SC. Risk of stroke in children: ethnic and gender disparities. Neurology. 2003;61:189–94. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000078894.79866.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hurn PD, Macrae IM. Estrogen as a neuroprotectant in stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20:631–652. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200004000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vannucci SJ, Willing LB, Goto S, Alkayed NJ, Brucklacher RM, Wook TL, et al. Experimental stroke in the female diabetic, db/db, mouse. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:52–60. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200101000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Du L, Bayir H, Lai Y, Zhang X, Kochanek PM, Watkins SC, et al. Innate gender-based proclivity in response to cytotoxicity and programmed cell death pathway. J BiolChem. 2004;279:38563–70. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405461200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta NC, Davis CM, Nelson JW, Young JM, Alkayed NJ. Soluble epoxide hydrolase: sex differences and role in endothelial cell survival. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:1936–42. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.251520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu M, Hurn PD, Roselli CE, Alkayed NJ. Role of P450 aromatase in sex-specific astrocytic cell death. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:135–411. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heyer A, Hasselblatt M, von Ahsen N, Hafner H, Siren AL, Ehrenreich H. In vitro gender differences in neuronal survival on hypoxia and in 17beta-estradiol-mediated neuroprotection. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:427–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma J, Nelluru G, Wilson MA, Johnston MV, Hossain MA. Sex-specific activation of cell death signaling pathways in cere- bellar granule neurons exposed to oxygen glucose deprivation followed by reoxygenation. ASN Neuron. 2011;3:85–97. doi: 10.1042/AN20100032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li H, Pin S, Zeng Z, Wang MM, Andreasson KA, McCullough LD. Sex differences in cell death. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:317–21. doi: 10.1002/ana.20538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Appelros P, Stegmayr B, Terent A. A review on sex differences in stroke treatment and outcome. Acta Neurol Scand. 2010;121:359–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2009.01258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gall SL, Tran PL, Martin K, Blizzard L, Srikanth V. Sex differences in long-term outcomes after Stroke: Functional outcomes, handicap and quality of life. Stroke. 2012;43:1982–1987. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.632547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bushnell CD, Reeves MJ, Zhao X, Pan W, Prvu-Bettger J, Zinner L, et al. Sex differences in quality of life after ischemic stroke. Neurol. 2014;82:922–31. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chamorro A, Meisel A, Planas AM, Urra X, van de Beek D, Veltkamp R. The immunology of acute stroke. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012;8:401–10. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vogelgesang A, Dressel A. Immunological consequences of ischemic stroke:immunosuppression and autoimmunity. J Neuroimmunol. 2011;231:105–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2010.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Offner H, Vandenbark AA, Hurn PD. Effect of experimental stroke on peripheral immunity: CNS ischemia induces profound immunosuppression. Neuroscience. 2009;158:1098–111. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Emsley HCA, Hopkins SJ. Acute ischaemic stroke and infection: recent and emerging concepts. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:341–53. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70061-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chamorro A, Urra X, Planas AM. Infection after acute ischemic stroke: a manifestation of brain –induced immunodepression. Stroke. 2007;38:1097–103. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000258346.68966.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Offner H, Subramanian S, Parker SM, Wang C, Afentoulis ME, Vandenbark AA, et al. Experimental stroke induces massive, rapid activation of the peripheral immune system. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:654–665. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Offner H, Subramanian S, Parker SM, Wang C, Afentoulis ME, Lewis A, et al. Splenic atrophy in experimental stroke is accompanied by increased regulatory T cells and circulating macrophages. J Immunol. 2006;176:6523–6531. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.11.6523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hurn PD, Subramanian S, Parker SM, Afentoulis ME, Kaler LJ, Vandenbark AA, et al. T- and B-cell-deficient mice with experimental stroke have reduced lesion size and inflammation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:1798–1805. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Subramanian S, Zhang B, Kosaka Y, Burrows GG, Grafe MR, Vandenbark AA, et al. Recombinant T cell receptor ligand treats experimental stroke. Stroke. 2009;40:2539–2545. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.543991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang B, Subramanian S, Dziennis S, Jia J, Uchida M, Akiyoshi K, et al. Estradiol and G1 reduce infarct size and improve immunosuppression after experimental stroke. J Immunol. 2010;184:4087–4094. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Akiyoshi K, Dziennis S, Palmateer J, Ren X, Vandenbark AA, Offner H, et al. Recombinant T Cell Receptor Ligands Improve Outcome After Experimental Cerebral Ischemia. Transl Stroke Res. 2011;2:404–410. doi: 10.1007/s12975-011-0085-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dziennis S, Akiyoshi K, Subramanian S, Offner H, Hurn PD. Role of dihydrotestosterone in post-stroke peripheral immunosuppression after cerebral ischemia. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25:685–95. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ren X, Akiyoshi K, Dziennis S, Vandenbark AA, Herson PS, Hurn PD, et al. Regulatory B cells limit CNS inflammation and neurologic deficits in murine experimental stroke. J Neurosci. 2011;31:8556–8563. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1623-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ren X, Akiyoshi K, Grafe MR, Vandenbark AA, Hurn PD, Herson PS, et al. Myelin specific cells infiltrate MCAO lesions and exacerbate stroke severity. Metab Brain Dis. 2012;27:7–15. doi: 10.1007/s11011-011-9267-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Offner H, Hurn P. A Novel Hypothesis: Regulatory B Lymphocytes Shape Outcome from Experimental Stroke. Translational Stroke Research. 2012;3:324–330. doi: 10.1007/s12975-012-0187-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Banerjee A, Wang J, Bodhankar S, Vandenbark AA, Murphy SJ, Offner H. Phenotypic changes in immune cell subsets reflect increased infarct volume in male vs. female mice. 2013;4:554–63. doi: 10.1007/s12975-013-0268-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pan J, Palmateer J, Schallert T, Hart M, Vandenbark AA, Offner H, Hurn PD. Novel humanized recombinant T cell receptor ligands protect the female brain after experimental stroke. Transl Stroke Res. 2014;5:577–85. doi: 10.1007/s12975-014-0345-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sahota P, Vahidy F, Nguyen C, Bui TT, Yang B, Parsha K, et al. Changes in spleen size in patients with acute ischemic stroke: a pilot observational study. Int J Stroke. 2013;8:60–7. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Planas AM, Gómez-Choco M, Urra X, Gorina R, Caballero M, Chamorro Á. Brain-derived antigens in lymphoid tissue of patients with acute stroke. J Immunol. 2012;188:2156–2163. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]