Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Zollinger–Ellison syndrome (ZES) is caused by uninhibited secretion of gastrin from a gastrinoma. Gastrinomas most commonly arise within the wall of the duodenum followed by the pancreas. Primary lymph node gastrinomas have also been reported in the literature. This is a case of ZES where preoperative localization revealed a gastrinoma in a solitary portacaval lymph node, presumed to be a primary lymph node gastrinoma.

PRESENTATION OF CASE

The patient is a 57 year old female diagnosed with ZES, suspected of having a primary lymph node gastrinoma. The patient underwent an exploratory laparotomy and excision of a portacaval lymph node with a frozen section which was positive for gastrinoma. Intraoperative sonography of the pancreas, upper endoscopy with transillumination of the duodenum, and a duodenotomy with bimanual examination of the duodenal wall were also performed. The patient was found to have a 4 mm duodenal mass near the pylorus, which was excised.

DISCUSSION

Pathology showed that the duodenal mass was primary gastrinoma. Serum gastrin levels taken four months postoperatively were normal and the repeat octreotide scan did not show any evidence of recurrence.

CONCLUSION

Primary lymph node gastrinoma is a diagnosis of exclusion. The duodenum and pancreas must be fully explored to rule out a primary gastrinoma that may be occult.

Keywords: Gastrinoma, Pancreas, Duodenum, Duodenotomy, Zollinger–Ellison syndrome

1. Introduction

Zollinger–Ellison syndrome (ZES) is characterized by severe peptic ulcer disease and often diarrhea caused by uninhibited secretion of gastrin from a gastrinoma that stimulates excessive production and release of gastric acid. Originally described as pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, gastrinomas are now known to most commonly arise within the wall of the duodenum (40–60%), followed by the pancreas (∼20%).1,2 We report a case of ZES where preoperative localization revealed a gastrinoma in a solitary portacaval lymph node, presumed to be a primary lymph node gastrinoma. On exploratory laparotomy, however, duodenotomy revealed a 4 mm primary duodenal gastrinoma near the pylorus, excision of which proved curative as determined by a regression to a normal fasting serum gastrin level. The case illustrates the diagnostic workup and operative procedures used to diagnose, localize, and treat gastrinoma with a subsequent review of the literature that explores landmark studies in the role of surgery in treating gastrinoma, the controversy over the existence of primary lymph node gastrinomas, and the importance of intraoperative exploration in the treatment of ZES.

2. Presentation of a case

A 57 year old woman presented three times to the emergency department over three weeks with recurrent complaints of nausea, vomiting and profuse watery diarrhea. The patient was empirically treated for Clostridium difficile (C. diff) colitis. All stool studies, including ova and parasites and C. diff toxins, were negative. In addition, a colonoscopy was negative for colitis or pseudo membranes, showing only pan-diverticulosis. After her symptoms appeared to improve with a course of antibiotics, she was discharged with outpatient follow-up only to return the following day with worsening diarrhea and multiple episodes of emesis. Her vitals continued to be normal with an unremarkable physical exam.

Further workup with abdominal computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed severe thickening and edema of the second through fourth portions of the duodenum with focal outpouchings of air suggestive of duodenal ulcers caused by a gastrinoma. The diagnosis was confirmed with a secretin stimulation test revealing a basal gastrin level of 1675 pg/ml which rose to 17,488 pg/ml after 10 min, exceeding the commonly accepted diagnostic threshold of a rise >200 pg/ml.3

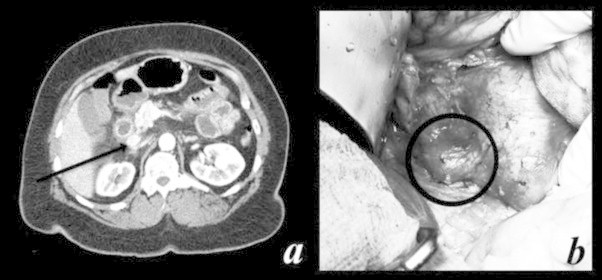

A preoperative localization attempt was made with esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), which revealed multiple ulcers throughout the duodenum, and endoscopic ultra sound (EUS), which revealed an enlarged portacaval node measuring 16 mm by 19 mm with no other suspicious findings. Preoperative octreotide scan demonstrated an area of focal abnormal octreotide uptake that corresponded to an enhancing portacaval node seen on CT (Fig. 1a) and on contrast-enhanced MRI. No other areas of uptake were identified. She was started on a high dose proton pump inhibitor (PPI) with improvement of symptoms.

Fig. 1.

Computed tomography (CT) scan of abdomen. (a) Portacaval node on CT scan of abdomen, corresponding to area of abnormal octreotide uptake on octreotide scan. (b) Intraoperative image of the portocaval node which was positive for gastrinoma on frozen and final pathology.

After a second EUS showed resolution of the ulcers and inflammation after a few weeks of PPI treatment, the patient underwent operative exploration with curative intent. The right colon was mobilized and the duodenum Kocherized to reveal the pathological portacaval node (Fig. 1b) situated just posterior to the head of the pancreas and portal triad, and anterior to the vena cava. The node was carefully excised using sharp dissection. An intraoperative frozen section was sent to pathology and was found to be positive for gastrinoma.

Intraoperative sonography was performed on both the pancreas and the area of the portacaval node with no abnormal lesions noted. Upper endoscopy with transillumination of the duodenum also yielded no abnormalities. Finally, a 5 cm longitudinal duodenotomy was created. Digital and bimanual examination of the entire wall of the duodenum (Fig. 2a) from the pylorus to the third portion was performed. A 4 mm firm nodule was palpated at the anterior inferior wall of the proximal duodenum just distal to the pylorus. The nodule was excised full thickness from the outer duodenal wall (Fig. 2b and c) and a frozen section submitted to pathology was consistent with a gastrinoma. The duodenotomy was closed transversely in two layers as was the opening at the site of the excision of the duodenal lesion.

Fig. 2.

Excision of gastrinoma. (a) Manual palpation of duodenum after duodenotomy. (b) Duodenal nodule, found to be gastrinoma. (c) Defect in the duodenal wall after enucleation, this was primarily closed.

The final pathology confirmed the duodenal nodule as the gastrinoma primary. The patient's post-operative course was uneventful and she was discharged home one week later. Four months postoperatively, her fasting gastrin level was 77 pg/ml and serotonin level was 152 ng/ml, both within normal limits. Patient also underwent a repeat octreotide scan which did not show any evidence of recurrence.

3. Discussion

The treatment for ZES has evolved as our understanding of the natural course of the disease has grown along with the development of anti-acid medications. Historically, gastrectomy was the treatment of choice; however, current medical management with proton pump inhibitors effectively controls gastric acid hypersecretion with a resultant resolution of symptoms.4 Sixty to 90 percent of gastrinomas are malignant with the potential to metastasize to the liver, which accounts for the vast majority of morbidity and mortality associated with ZES and the rationale for surgical intervention.1 Although the majority of gastrinomas are slow growing, roughly 25 percent exhibit rapid growth and present with concurrent liver metastasis, an indicator of an aggressive disease course with a significantly worsened prognosis.5 In a series of 160 patients who underwent surgical resection of gastrinomas (no hepatic metastasis) vs. 35 patients managed with conservative medical approach, surgery was shown to achieve long-term cure in 41 percent with a greatly reduced likelihood of liver metastasis (29% vs. 5%, p = 0.0002), and prolonged 15-year survival (98% vs. 74%, p = 0.0002).1 Based on this study and on smaller series that have reached similar conclusions, patients with sporadic gastrinomas who do not have evidence of liver metastases should be offered exploratory laparotomy and resection with curative intent.6,7 In contrast, the role of surgery for patients with gastrinoma in the context of MEN1 (20% of patients with ZES), hepatic metastases, and those with occult disease with no primary tumor identified preoperatively remains complicated and controversial.8

The existence of primary lymph node gastrinomas is a much debated and controversial topic in the literature.9–12 There have been many reports of patients with ZES who had only lymph nodes resected and were cured as assessed by biochemical testing and imaging studies in both the short and long term.13–16 Of those gastrinomas not localized to the duodenum or pancreas, the most common site of gastrinoma occurrence is within a lymph node found in the gastrinoma triangle, an area defined as the confluence of the cystic and common bile duct superiorly, the second and third portions of the duodenum inferiorly, and the neck and body of the pancreas medially, both dorsally and ventrally.17 Norton et al. showed in a series of 176 patients with ZES (138 sporadic, 38 MEN1) that 26 of 45 patients were disease free soon after lymph node only resection, 18 of which (10%) remained disease-free after an average of 10.4 years follow up while 8 (5%) relapsed, resulting in reoperation in 4 patients, of which 3 were found to have a duodenal primary gastrinoma.10 It has been theorized that pancreatic stem cells from the ventral pancreatic bud become dispersed and are incorporated into lymph tissue and the duodenal wall during embryonic development, which is supported by pathological studies that report findings of neuroendocrine cells in the region almost exclusively defined by the gastrinoma triangle.17–19

However, even with the likely existence of a primary lymph node gastrinoma, this remains a diagnosis of exclusion. Norton et al. emphasized that a missed duodenal primary tumor could easily be mistaken for a primary lymph node gastrinoma.10 Even when imaging is negative for sporadic ZES, routine surgical exploration is warranted to minimize the chance of metastasis to the liver; an experienced surgeon can find a gastrinoma in nearly every patient with negative imaging and achieve similar cure rates as compared to patients with positive imaging.20 In addition, Zogakis et al. showed in a series of 63 patients with a primary duodenal gastrinoma that only 10 percent of the primary gastrinomas were found preoperatively as their small size precludes detection.21 Intraoperative techniques used to localize a gastrinoma include sonogram, transillumination, and duodenotomy, which have been shown to detect significantly more gastrinomas (94% vs. 64%), resulting in a higher cure rate.22 In another analysis of his cohort, Norton et al. showed that use of duodenotomy specifically increased both the short and long term cure rates.23

4. Conclusion

Once a diagnosis of sporadic gastrinoma has been made, a complete intraoperative search for a primary, including duodenotomy with total tumor excision should be the standard of care to maximize the chance for cure and minimizing further morbidity and mortality associated with either a repeat operation or metastasis.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

IRB Exemption Status was obtained for the Case Report.

Author contributions

All authors participated in study concept/design, data collection and analysis and writing of the paper.

Key learning points.

-

•

Even when imaging is negative for sporadic Zollinger–Ellison Syndrome, surgical exploration is warranted to minimize the chance of metastasis to the liver.

-

•

Duodenotomy is Warranted During Surgical Exploration for a Suspected Primary lymph node gastrinoma.

References

- 1.Norton J.A., Fraker D.L., Alexander H.R., Gibril F., Liewehr D.J., Venzon D.J. Surgery increases survival in patients with gastrinoma. Ann Surg. 2006;244(3):410–419. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000234802.44320.a5. [Epub 2006/08/24] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pipeleers-Marichal M., Donow C., Heitz P.U., Kloppel G. Pathologic aspects of gastrinomas in patients with Zollinger–Ellison syndrome with and without multiple endocrine neoplasia type I. World J Surg. 1993;17(4):481–488. doi: 10.1007/BF01655107. [Epub 1993/07/01] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berger A.C., Gibril F., Venzon D.J., Doppman J.L., Norton J.A., Bartlett D.L. Prognostic value of initial fasting serum gastrin levels in patients with Zollinger–Ellison syndrome. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2001;19(12):3051–3057. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.12.3051. [Epub 2001/06/16] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirschowitz B.I., Mohnen J., Shaw S. Long-term treatment with lansoprazole of patients with duodenal ulcer and basal acid output of more than 15 mmol/h. Aliment Pharmacol Therap. 1996;10(4):497–506. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1996.11153000.x. [Epub 1996/08/01] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weber H.C., Venzon D.J., Lin J.T., Fishbein V.A., Orbuch M., Strader D.B. Determinants of metastatic rate and survival in patients with Zollinger–Ellison syndrome: a prospective long-term study. Gastroenterology. 1995;108(6):1637–1649. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90124-8. [Epub 1995/06/01] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atema J.J., Amri R., Busch O.R., Rauws E.A., Gouma D.J., Nieveen van Dijkum E.J. Surgical treatment of gastrinomas: a single-centre experience. HPB: Off J Int Hepato Pancreato Biliary Assoc. 2012;14(12):833–838. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2012.00551.x. [Epub 2012/11/09] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Neuroendocrine Tumors (Version 2.2014) http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/neuroendocrine.pdf [cited 15.03.14].

- 8.Norton J.A., Jensen R.T. Resolved and unresolved controversies in the surgical management of patients with Zollinger–Ellison syndrome. Ann Surg. 2004;240(5):757–773. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000143252.02142.3e. [Epub 2004/10/20] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howard T.J., Zinner M.J., Stabile B.E., Passaro E., Jr. Gastrinoma excision for cure. A prospective analysis. Ann Surg. 1990;211(1):9–14. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199001000-00002. [Epub 1990/01/01] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norton J.A., Alexander H.R., Fraker D.L., Venzon D.J., Gibril F., Jensen R.T. Possible primary lymph node gastrinoma: occurrence, natural history, and predictive factors: a prospective study. Ann Surg. 2003;237(5):650–657. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000064375.51939.48. [discussion 7–9]. [Epub 2003/05/02] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arnold W.S., Fraker D.L., Alexander H.R., Weber H.C., Norton J.A., Jensen R.T. Apparent lymph node primary gastrinoma. Surgery. 1994;116(6):1123–1129. [discussion 9–30]. [Epub 1994/12/01] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delcore R., Jr., Cheung L.Y., Friesen S.R. Outcome of lymph node involvement in patients with the Zollinger–Ellison syndrome. Ann Surg. 1988;208(3):291–298. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198809000-00006. [Epub 1988/09/01] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolfe M.M., Alexander R.W., McGuigan J.E. Extrapancreatic, extraintestinal gastrinoma: effective treatment by surgery. N Engl J Med. 1982;306(25):1533–1536. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198206243062506. [Epub 1982/06/24] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vogel S.B., Wolfe M.M., McGuigan J.E., Hawkins I.F., Jr., Howard R.J., Woodward E.R. Localization and resection of gastrinomas in Zollinger–Ellison syndrome. Ann Surg. 1987;205(5):550–556. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198705000-00014. [Epub 1987/05/01] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farley D.R., van Heerden J.A., Grant C.S., Miller L.J., Ilstrup D.M. The Zollinger–Ellison syndrome. A collective surgical experience. Ann Surg. 1992;215(6):561–569. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199206000-00002. [discussion 9–70]. [Epub 1992/06/01] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou H., Schweikert H.U., Wolff M., Fischer H.P. Primary peripancreatic lymph node gastrinoma in a woman with MEN1. J Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surg. 2006;13(5):477–481. doi: 10.1007/s00534-006-1111-7. [Epub 2006/10/03] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Passaro E., Jr., Howard T.J., Sawicki M.P., Watt P.C., Stabile B.E. The origin of sporadic gastrinomas within the gastrinoma triangle: a theory. Arch Surg. 1998;133(1):13–16. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.133.1.13. [discussion 7]. [Epub 1998/01/23] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herrmann M.E., Ciesla M.C., Chejfec G., DeJong S.A., Yong S.L. Primary nodal gastrinomas. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124(6):832–835. doi: 10.5858/2000-124-0832-PNG. [Epub 2000/06/03] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perrier N.D., Batts K.P., Thompson G.B., Grant C.S., Plummer T.B. An immunohistochemical survey for neuroendocrine cells in regional pancreatic lymph nodes: a plausible explanation for primary nodal gastrinomas? Mayo Clinic Pancreatic Surgery Group. Surgery. 1995;118(6):957–965. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(05)80100-x. [discussion 65–6]. [Epub 1995/12/01] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norton J.A., Fraker D.L., Alexander H.R., Jensen R.T. Value of surgery in patients with negative imaging and sporadic Zollinger–Ellison syndrome. Ann Surg. 2012;256(3):509–517. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318265f08d. [Epub 2012/08/08] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zogakis T.G., Gibril F., Libutti S.K., Norton J.A., White D.E., Jensen R.T. Management and outcome of patients with sporadic gastrinoma arising in the duodenum. Ann Surg. 2003;238(1):42–48. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000074963.87688.31. [Epub 2003/07/02] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Norton J.A., Doppman J.L., Jensen R.T. Curative resection in Zollinger–Ellison syndrome. Results of a 10-year prospective study. Ann Surg. 1992;215(1):8–18. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199201000-00012. [Epub 1992/01/01] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Norton J.A., Alexander H.R., Fraker D.L., Venzon D.J., Gibril F., Jensen R.T. Does the use of routine duodenotomy (DUODX) affect rate of cure, development of liver metastases, or survival in patients with Zollinger–Ellison syndrome? Ann Surg. 2004;239(5):617–625. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000124290.05524.5e. [discussion 26]. [Epub 2004/04/15] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]